Abstract

Mini-gastric bypass/one anastomosis gastric bypass (MGB/OAGB) is an emerging weight loss surgical procedure. There are serious concerns not only regarding the symptomatic biliary reflux into the stomach and the oesophagus but also the increased risk of malignancy after MGB/OAGB. A 54-year-old male, with a body mass index (BMI) of 46.1 kg/m2, underwent Robotic MGB at another centre on 22nd June 2016. His pre-operative upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was not done. He lost 58 kg within 18 months after the surgery and attained a BMI of 25.1 kg/m2. However, 2-year post-MGB, the patient had rapid weight loss of 19 kg with a decrease in BMI to 18.3 kg/m2 within a span of 2 months. He also developed progressive dysphagia and had recurrent episodes of non-bilious vomiting. His endoscopy showed eccentric ulcerated growth in lower oesophagus extending up to the gastro-oesophageal junction and biopsy reported adenocarcinoma of oesophagus. MGB/OAGB has a potential for bile reflux with increased chances of malignancy. Surveillance by endoscopy at regular intervals for all patients who have undergone MGB/OAGB might help in early detection of Barrett's oesophagus or carcinoma of oesophagus or stomach.

Keywords: Bariatric surgery, Barrett's oesophagus, biliary reflux, oesophageal carcinoma, gastric carcinoma, one anastomosis gastric bypass

INTRODUCTION

Mini-gastric bypass/one anastomosis gastric bypass (MGB/OAGB) first reported by Rutledge is an emerging weight loss surgical procedure.[1] It is found to be safe and effective in terms of successful weight loss and resolution of obesity-related comorbidities.[1] Nevertheless, it has been viewed with scepticism with serious concerns not only regarding the symptomatic biliary reflux (BR) into the stomach and the oesophagus[2,3,4] but also the increased risk of malignancy after MGB/OAGB.[3,5]

To the best of our knowledge, no case of oesophageal or gastric carcinoma has been reported post-MGB/OAGB. We report a case of oesophageal carcinoma involving the gastro-oesophageal junction detected 2 years after MGB/OAGB done at another centre.

CASE REPORT

A 54-year-old male, with a body mass index (BMI) of 46.1 kg/m2, underwent Robotic MGB/OAGB at another centre on 22nd June 2016. He had no major comorbidities. There was no history of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD). However, pre-operative upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGIE) was not done. The patient was a known smoker (10–12 cigarettes/day) and used to consume 60–70 ml of alcohol by volume (ABV) daily. The procedure was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on the 5th post-operative day. He lost 58 kg within 18 months after the surgery and attained a BMI of 25.1 kg/m2. The patient did not follow-up after bariatric surgery. He had also started to smoke (6–7 cigarettes/day) and consume alcohol daily (25–35 ml, ABV), 4 months after surgery.

For the past 6 months, the patient had rapid weight loss along with multiple episodes of severe loose stools. In the past 2 months, the patient had a significant weight loss of 19 kg with a decrease in BMI to 18.3 kg/m2. He also had hypoglycaemic episodes and generalised body weakness. There were no symptoms of GERD. He also developed progressive dysphagia; initially, more for solids which rapidly progressed to liquids. He also had recurrent episodes of non-bilious vomiting. There was no history of haematemesis, haemoptysis or melena.

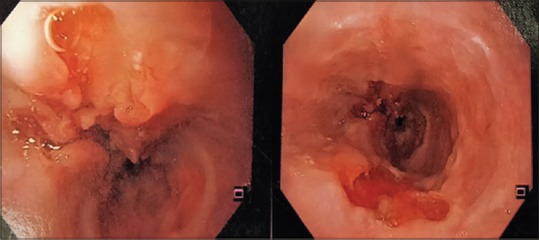

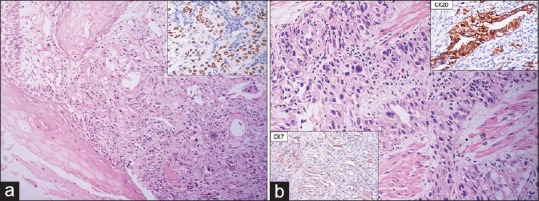

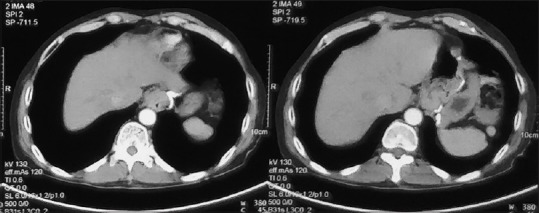

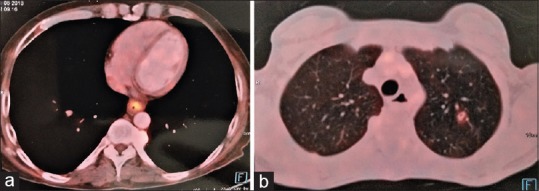

He underwent UGIE at a private centre which showed eccentric ulcerated growth in lower oesophagus extending up to the gastro-oesophageal junction [Figure 1]. The biopsy was reported as adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus. Histopathological review of the slides at our centre revealed the presence of a tumour composed of intermingled adenocarcinomatous and squamous carcinomatous components. The superficially located tumour islands showed squamous differentiation (immunopositivity for p40), whereas glandular differentiation was more obvious in the deeper portion of tumour. The tumour was seen infiltrating in between the smooth muscle bundles [Figure 2a and b]. The adenocarcinoma component was found to be immunoreactive for CK20 and focally for CK7 (weak to moderate). Computerised tomography of the chest and abdomen showed a growth in the distal oesophagus extending up to the cardio-oesophageal junction. The fat planes were maintained and there was no mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathy [Figure 3]. Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography showed the presence of hypermetabolic circumferential wall mucosal thickening involving the lower oesophagus extending to involve the gastro-oesophageal junction and the adjacent cardia of the stomach. In addition, there was also a small mildly hypermetabolic subcentimetric fibrocavitary lesion in the upper lobe of the left lung [Figure 4a and b].

Figure 1.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showing irregular growth in the lower oesophagus extending to gastro-oesophageal junction

Figure 2.

(a) Microscopic appearance of tumour infiltrating into oesophageal mucosa and showing both squamous and glandular differentiation (H and E, ×200); immunopositivity for p40, highlighting the squamous component (inset) (H and E). (b) Adenocarcinoma component infiltrating in between smooth muscle bundles (H and E, ×200); immune-stained for CK20 and CK7 (inset)

Figure 3.

Computerised tomography scan of the chest and abdomen images – left image showing lower oesophageal irregular growth, whereas right image showing extension to gastro-oesophageal junction with maintained fat planes and no hilar lymphadenopathy

Figure 4.

(a) Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography scan showed hypermetabolic circumferential wall mucosal thickening involving lower oesophagus extending to involve gastro-oesophageal junction and adjacent cardia of stomach. (b) Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography scan showed small mildly hypermetabolic subcentimetric fibrocavitary lesion in left lung upper lobe

At present, the patient is being managed by a multi-disciplinary team comprising gastrointestinal surgeons, oncologist and bariatric surgeons at our centre. The patient has been planned for neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by transhiatal oesophagectomy.

DISCUSSION

MGB/OAGB is emerging as a popular procedure all over the world for several reasons like relative simplicity involving the creation of a long gastric pouch with a single antecolic jejunal loop. Gastrojejunal anastomosis avoids the Roux-en-Y limb construction and the need for closure of internal hernia defects. It also has a shorter learning curve as compared to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB).[3] However, there is a concern regarding BR and risk of subsequent oesophageal malignancy. Scozzari et al.[6] reported 33 cases of oesophageal and gastric cancer in patients following bariatric surgery out of which restrictive procedures had been performed in 15 patients (45.5%), namely vertical banded gastroplasty (27.2%), gastric banding (15.1%) and sleeve gastrectomy (3%). Gastric bypass was performed in rest 18 patients (54.5%) of which 14 patients (42.4%) underwent RYGB and rest 4 patients (12.1%) underwent loop gastric bypass. Of the total four cases reported in loop gastric bypass, in three cases, tumour was present in excluded stomach and one in gastric pouch. The mean duration of detection of neoplasms after bariatric surgery is 8.5 years (2 months–29 years).[6] However, to the best of our knowledge, no case of oesophageal carcinoma extending up to gastro-oesophageal junction has been reported in the literature following MGB/OAGB.

The Billroth II gastrectomy is known to be associated with three times increased risk of proximal gastric remnant cancer compared to the general population.[7] BR gastritis after MGB/OAGB and its potential to increase chances of malignancy is a controversial issue. BR is known to cause histological changes in oesophagus and gastric pouch, secondary to acute and chronic inflammatory changes in oesophageal and gastric mucosa. These changes might progress to premalignant condition, Barrett's oesophagus.[8] Under the influence of constant BR, Barrett's oesophagus can progress to an incomplete intestinal metaplasia (Type III) instead of complete intestinal metaplasia (Type I) which has a higher risk of gastro-oesophageal cancer development.[9] This impact of BR and the development of adenocarcinoma can further be strengthened by the fact that there is an increased risk of neoplasm both in gastric pouch and remnant stomach after RYGB.[10] Even though remnant stomach is devoid of contact with exogenous carcinogens, it comes in prolonged contact with a pool of bile and pancreatico-BR which has potential to cause malignancy.[11]

Our patient presented with symptoms 2 years after OAGB. He presented with continued weight loss which was initially attributed to the effect of bariatric surgery. The patient was a known smoker. However, the temporality of association of his symptoms to the surgery suggests MGB/OAGB to be the leading cause of development of carcinoma. The patient was evaluated only when he developed significant dysphagia. Thus, there was a delay in the diagnosis. The symptoms of weight loss with dysphagia and vomiting cannot strictly be attributed as benign symptoms associated after bariatric surgery. They should be investigated thoroughly keeping rare possibility of carcinoma in mind. Morbid obesity itself is an independent risk factor for the development of oesophagogastric carcinoma, especially oesophageal carcinoma.[12] Furthermore, morbid obesity aggravates GERD leading to oesophagitis and subsequently Barrett's oesophagus and oesophageal carcinoma.[13] Another possibility is that our patient was harbouring Barrett's oesophagus preoperatively, which later progressed to adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus, aggravated by constant BR. UGIE should be routinely done as a part of the pre-operative workup of all bariatric surgery patients to rule out Barrett's oesophagus or malignant conditions of oesophagus and stomach.[14] Surveillance by endoscopy at regular intervals for all patients who have undergone MGB/OAGB might help in early detection of Barrett's oesophagus or carcinoma of oesophagus or stomach.

CONCLUSION

MGB/OAGB has a potential for bile reflux with increased chances of malignancy. We report the first case of malignancy of lower oesophagus extending up till the gastro-oesophageal junction following MGB/OAGB.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rutledge R. The mini-gastric bypass: Experience with the first 1,274 cases. Obes Surg. 2001;11:276–80. doi: 10.1381/096089201321336584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson WH, Fernanadez AZ, Farrell TM, Macdonald KG, Grant JP, McMahon RL, et al. Surgical revision of loop (“mini”) gastric bypass procedure: Multicenter review of complications and conversions to roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noun R, Skaff J, Riachi E, Daher R, Antoun NA, Nasr M, et al. One thousand consecutive mini-gastric bypass: Short- and long-term outcome. Obes Surg. 2012;22:697–703. doi: 10.1007/s11695-012-0618-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahawar KK, Carr WR, Balupuri S, Small PK. Controversy surrounding ‘mini’ gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2014;24:324–33. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-1090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Musella M, Milone M. Still “controversies” about the mini gastric bypass? Obes Surg. 2014;24:643–4. doi: 10.1007/s11695-014-1193-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scozzari G, Trapani R, Toppino M, Morino M. Esophagogastric cancer after bariatric surgery: Systematic review of the literature. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:133–42. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacDonald WC, Owen DA. Gastric carcinoma after surgical treatment of peptic ulcer: An analysis of morphologic features and a comparison with cancer in the nonoperated stomach. Cancer. 2001;91:1732–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010501)91:9<1732::aid-cncr1191>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dixon MF, Neville PM, Mapstone NP, Moayyedi P, Axon AT. Bile reflux gastritis and Barrett's oesophagus: Further evidence of a role for duodenogastro-oesophageal reflux? Gut. 2001;49:359–63. doi: 10.1136/gut.49.3.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filipe MI, Muñoz N, Matko I, Kato I, Pompe-Kirn V, Jutersek A, et al. Intestinal metaplasia types and the risk of gastric cancer: A cohort study in Slovenia. Int J Cancer. 1994;57:324–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910570306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raijman I, Strother SV, Donegan WL. Gastric cancer after gastric bypass for obesity. Case report. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;13:191–4. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199104000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trincado MT, del Olmo JC, García Castaño J, Cuesta C, Blanco JI, Awad S, et al. Gastric pouch carcinoma after gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2005;15:1215–7. doi: 10.1381/0960892055002383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hampel H, Abraham NS, El-Serag HB. Meta-analysis: Obesity and the risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease and its complications. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:199–211. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-3-200508020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corley DA, Kubo A, Levin TR, Block G, Habel L, Zhao W, et al. Abdominal obesity and body mass index as risk factors for Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:34–41. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Moura Almeida A, Cotrim HP, Santos AS, Bitencourt AG, Barbosa DB, Lobo AP, et al. Preoperative upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery: Is it necessary? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:144–9. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]