Abstract

Context:

Retrorectal tumours are rare with developmental cysts being the most common type. Conventionally, large retrorectal developmental cysts (RRDCs) require the combined transabdomino-sacrococcygeal approach.

Aims:

This study aims to investigate the surgical outcomes of the laparoscopic approach for large RRDCs.

Settings and Design:

A retrospective case series analysis.

Subjects and Methods:

Data of patients with RRDCs of 10 cm or larger in diameter who underwent the laparoscopic surgery between 2012 and 2017 at our tertiary centre were retrospectively analyzed.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Results are presented as median values or mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and numbers (percentages) for categorical variables.

Results:

Twenty consecutive cases were identified (19 females; median age, 36 years). Average tumour size was 10.9 ± 1.1 cm. Cephalic ends of lesions ranged from S1/2 junction to S4 level. Caudally, 18 cysts extended to the sacrococcygeal hypodermis. Seventeen patients underwent the pure laparoscopy; three patients received a combined laparoscopic-posterior approach. The operating time was 167.1 ± 57.3 min for the pure laparoscopic group and 212.0 ± 24.5 min for the combined group. The intraoperative haemorrhage was 68.2 ± 49.7 and 66.7 ± 28.9 (mL), respectively. Post-operative complications included one trocar site hernia, one wound infection and one delayed rectal wall perforation. The median post-operative hospital stay was 7 days. With a median follow-up period of 36 months, 1 lesions recurred.

Conclusions:

The laparoscopic approach can provide a feasible and effective alternative for large RRDCs, with advantages of the minimally invasive surgery. For lesions with ultra-low caudal ends, especially those closely clinging to the rectum, a combined posterior approach is still necessary.

Keywords: Developmental cyst, laparoscopy, presacral tumour, retrorectal tumour

INTRODUCTION

Tumours that occur in the retrorectal space comprise an uncommon and heterogeneous group, with two-thirds being congenital lesions.[1,2,3] Although the true incidence of retrorectal tumours (RTs) is unknown, it is early estimated at one in every 40,000–63,000 admissions to large referral centres.[3,4] Being the most common congenital RTs, retrorectal developmental cysts (RRDCs) in adults are a relatively common entity, which tends to occur more frequently in females, with a reported male: female ratio ranging from 1:1.8 to 1:15.[1,3,5] Depending on the embryonic cell of origin, RRDCs can be sub-classified as epidermoid, dermoid, tailgut cyst or cystic teratomas. Although most RRDCs are benign, retrorectal teratomas can be malignant, with an estimated risk of malignant transformation of 5%–10%.[2,3,6,7]

Due to the covert location and the relatively slow and non-invasive growth pattern of RRDCs, many patients are asymptomatic or present with only unspecific symptoms. A number of RRDCs are incidentally discovered during examinations for other reasons, such as routine health checks.[8,9,10,11] When RRDCs grow to a large size, however, they may present with mass effect symptoms including dull pain in the lower back or the sacrococcygeal region, constipation, frequent or difficult urination and even causing obstructive dystocia in women.[1,12] Spontaneous infection can occur in up to one-third of RRDCs, and even developing fistulas to the sacrococcygeal skin or into the rectum.[5,7,12] Previous literatures demonstrated that a benign RRDC may harbour malignant components or become malignant with time going by, although uncommon.[2,5] It is generally believed that surgical excision is indicated for all RRDCs, even for asymptomatic benign ones.[2,3,10,11,13]

Conventionally, RTs are removed by the transsacrococcygeal (posterior) approach, the transabdominal (anterior) approach or the combined abdomino-sacrococcygeal approach, according to the type, location and size of the lesion.[3,6,11,14,15,16] For RRDCs, the posterior approach is predominantly advocated because these lesions commonly have a dense adherence to the coccyx.[1,17] For large cysts higher than the S3 level, however, an additional transabdominal approach is usually needed.

Since the mid-1990s, the laparoscopic resection of RTs has been reported, first being described by Sharpe and Van Oppen in 1995.[18] From then on, several authors have reported their experiences upon the laparoscopic approach for RTs, mostly as case reports or short series.[9,19,20,21,22] Among these, Duclos et al. reported the largest series of 12 cases in 2013.[21]

The aim of this study was to review our single-centre experiences on the laparoscopic approach for large RRDCs, a clinically challenging disease, with a relatively large sample size.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Patients

This was a retrospective study being performed using a prospectively maintained database of our tertiary care centre. Clinical data of consecutive patients with RRDCs who underwent the laparoscopic resection from December 2012 to October 2017 were reviewed. Cases of retrorectal Schwannoma, leiomyoma, anterior sacral meningocele, lesions smaller than 10 cm or those being excised by the laparotomy were excluded. Patient demographics, symptoms, physical findings, imaging characteristics, surgical interventions, pathology, intra- and post-operative complications and post-operative hospital stay were all documented. Imaging data of the computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) retrieved from the electronic radiological database were re-studied. Detailed parameters including the sacral level of the lesions were added to the imaging records. Histological slices of the surgical specimens were re-examined by a pathologist to confirm the pathological diagnosis. The patients were followed up at the outpatient clinic and by regular telephone interviews. The long-term complications and the recurrences were recorded. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital.

Surgical technique

The patient is placed in a Trendelenburg position. Four or five ports were placed in a similar pattern as that for the laparoscopic anterior resection for rectal cancer. Dissection begins from right or left side of the upper mesorectum above the sacral promontory, according to the location of the lesion. After the retroperitoneum is opened with a harmonic scalpel, the flimsy areolar tissue in the plane between the mesorectal fascia and the pre-hypogastric nerve fascia is identified. Along this plane, dissection proceeds downwards and bilaterally, entering the retrorectal space. Dissection continues downwards until the top of the lesion is revealed [Figure 1a]. Layers of fibrous tissue (the pseudocapsules) are carefully incised to reveal the true capsule of the lesion. Then, the tumour is carefully stripped off the adjacent structures along the true capsule [Figure 1b]. Care must be taken to identify the mesorectum and prevent injuring the rectum, which is often pushed aside against the pelvic sidewall [Figure 1c]. Posteriorly, the pre-hypogastric nerve fascia is kept intact to safeguard the pelvic autonomic nerves [Figure 1a] and prevent injuries to the presacral venous plexus. At the level of lower sacrum and coccyx, where the cysts always being densely adherent to the bony structure, the dissection needs to be kept close to the anterior surface of the bone, so as to thoroughly remove the adhesive parts of the lesion. For the lesions extending caudally to below the pelvic floor, its attachment to the levator ani muscles are severed [Figure 1d], and the caudal end dissected off until the entire lesion can be removed. Finally, the specimen is extracted using a laparoscopic retrieval bag (Endocatch Gold 10 mm; Surgical Corporation, Norwalk, CT, USA) through a prolonged trocar incision and the retrorectal space adequately irrigated. A drain can be placed in the surgical anatomic space and brought out through a trocar incision.

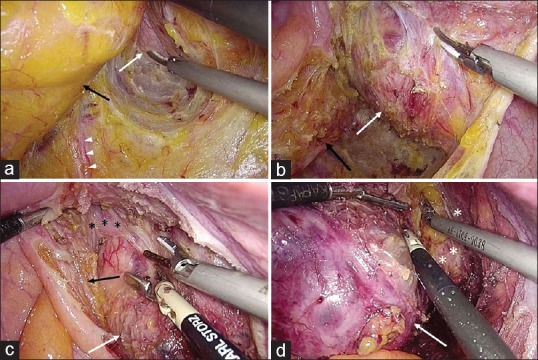

Figure 1.

Details of laparoscopic resection of a large retrorectal developmental cyst. (a) Dissection proceeds downwards along the retrorectal plane to reveal the cyst (white arrow). Prevent injuring the adjacent structures (black arrow, mesorectum; white arrow heads, inferior hypogastric nerve). (b) Dissect along the true capsule by incising the pseudo-capsules. (c) Meticulously identify the rectal wall (black asterisk signs) to prevent inadvertent injury. (d) After the attachment to the levator ani (White asterisk signs) is severed, the caudal end of the cyst is dissected off the ischiorectal fossa

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as median values or mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables, and numbers (percentages) for categorical variables. Analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 19.0 for Windows, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Data of 20 consecutive patients (1 male and 19 females) with large RRDCs who underwent laparoscopic resection in our department from December 2012 to October 2017 were retrieved from the database. Patient demographics, tumour characteristics and operative outcomes are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics, tumour characteristics and operative outcomes of 20 patients with large retrorectal developmental cysts

| n | Gender | Age | BMI | History of resection or aspiration | Symptoms | Cephalic level | Caudal level | Crossing pelvic floor | Largest diameter (cm) | Multilocular | Preoperative CEA level (ng/mL) | Pathology | Surgical approach | Operative time (min) | Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | Complications | PHS (day) | Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 47 | 21.8 | None | Difficult defecation | S1-2 | Subcutaneous | Y | 11.8 | N | NA | Epidermoid cyst | Laparoscopy | 180 | 20 | None | 3 | N |

| 2 | Female | 27 | 19.2 | None | None | S3-4 | Subcutaneous | Y | 10.2 | N | NA | Epidermoid cyst | Laparoscopy | 115 | 20 | None | 5 | N |

| 3 | Female | 31 | 21.1 | Posterior resection | None | S1-2 | Subcutaneous | Y | 11.5 | N | 8.73 | Mature teratoma with low-grade mucinous neoplasm | Laparoscopy | 95 | 30 | None | 3 | N |

| 4 | Female | 64 | 27.7 | None | None | S2 | Subcutaneous | Y | 10 | N | 1.49 | Dermoid cyst | Laparoscopy | 170 | 100 | Trocar site hernia | 5 | N |

| 5 | Female | 42 | 28.2 | None | None | S2 | Subcutaneous | Y | 11.5 | Y | 1.01 | Simple cyst | Laparoscopy | 90 | 20 | None | 6 | N |

| 6 | Female | 44 | 21.1 | None | Change in the bowel habit | S3-4 | Subcutaneous | Y | 10.5 | N | NA | Mature teratoma | Laparoscopy | 119 | 100 | None | 7 | N |

| 7 | Female | 49 | 32.0 | None | None | S2 | Tip of coccyx | Y | 10.5 | Y | NA | Epidermoid cyst | 3D-laparoscopy | 227 | 20 | None | 6 | N |

| 8 | Female | 48 | 29.7 | Transabdominal incision and drainage | Difficult defecation | S1-2 | Subcutaneous | Y | 11 | Y | 0.96 | Mature teratoma | Laparoscopy | 276 | 200 | Rectal perforation | 12 | N |

| 9 | Female | 34 | 24.0 | 1. Percutaneous incision and drainage; 2. Transvaginal aspiration | Abdominal distension | S3-4 | Subcutaneous | Y | 10.4 | Y | 1.26 | Epidermoid cyst | Laparoscopy | 132 | 100 | None | 6 | Y |

| 10 | Female | 38 | 20.8 | None | Sacrococcygeal pain | S1-2 | Subcutaneous | Y | 15 | Y | 1.04 | Mature teratoma | Laparoscopy + posterior | 236 | 100 | None | 7 | N |

| 11 | Female | 31 | 27.6 | None | Abdominal distension | S2 | Subcutaneous | Y | 10 | Y | 0.67 | Mature teratoma | Laparoscopy | 250 | 100 | None | 7 | N |

| 12 | Female | 22 | 20.3 | Percutaneous incision and drainage | None | S3-4 | Subcutaneous | Y | 11 | Y | NA | Epidermoid cyst | Laparoscopy | 165 | 50 | None | 7 | N |

| 13 | Female | 27 | 18.2 | None | Sacrococcygeal pain | S3-4 | Subcutaneous | Y | 10 | NA | NA | Epidermoid cyst | Laparoscopy | 122 | 20 | None | 7 | N |

| 14 | Female | 34 | 24.7 | Transabdominal resection | Sacrococcygeal pain with rectal tenesmus | S2-3 | Subcutaneous | Y | 10 | Y | 0.76 | Epidermoid cyst | Laparoscopy + enterostomy | 230 | 80 | None | 7 | N |

| 15 | Female | 43 | 26.8 | Transsacral resection | Difficult urination and defecation | S2 | Subcutaneous | Y | 10 | Y | NA | Mature teratoma with low-grade mucinous neoplasm | Laparoscopy + posterior | 213 | 50 | None | 7 | N |

| 16 | Female | 57 | 22.0 | None | Lower abdominal and sacrococcygeal pain | S4 | Subcutaneous | Y | 10.3 | Y | 9.49 | Mature teratoma with low-grade mucinous neoplasm | Laparoscopy + posterior | 187 | 50 | None | 6 | N |

| 17 | Male | 30 | 22.9 | Transsacral resection | Sacrococcygeal pain | S4 | Subcutaneous | Y | 11.5 | Y | 2.59 | Mature teratoma | Laparoscopy | 153 | 100 | None | 7 | N |

| 18 | Female | 23 | 19.0 | None | Abdominal pain and difficult defecation | S2-3 | Tip of coccyx | Y | 10.6 | N | NA | Epidermoid cyst | Laparoscopy | 123 | 20 | None | 8 | N |

| 19 | Female | 37 | 22.9 | None | None | S3-4 | Subcutaneous | Y | 11 | N | NA | Epidermoid cyst | Laparoscopy + enterostomy | 234 | 80 | None | 7 | N |

| 20 | Female | 35 | 30.0 | None | Abdominal pain | S3-4 | Subcutaneous | Y | 10.4 | Y | 19.18 | Teratoma with focal mucinous adenocarcinoma | Laparoscopy + enterostomy | 160 | 100 | Skin perforation | 22 | N |

BMI: Body mass index, CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen, PHS: Post-operative hospital stay, NA: Not available

The patient age ranged from 22 to 64 (median, 36) years old. The final pathological diagnoses included nine epidermoid cysts (45.0%), nine mature cystic teratomas (45.0%), one dermoid cyst (5.0%) and one simple cyst (5.0%). Among the nine cases of mature teratomas, one contained focal mucinous adenocarcinomas and another three had components of low-grade mucinous neoplasms. The average lesion size was 10.9 ± 1.1 cm in the largest diameter. Cephalic levels of the lesions ranged from S1/2 junction to S4, with nine cysts (45.0%) being entirely located below the S3 level. All the 20 cysts penetrated the pelvic floor muscles into the ischiorectal fossa. Eighteen cysts (90.0%) extended down to the subcutaneous layer of the sacrococcygeal region, the other two (10.0%) had higher caudal ends at the level of the coccygeal tip. Twelve out of 19 cases (63.2%) were identified multilocular lesions by the imaging studies [Figure 2a].

Figure 2.

Retrorectal developmental cysts are often multilocular lesions. The tumour ‘recurrence’ may sometimes due to the missing of one or more separately located cysts during the laparoscopic surgery, which should be more accurately defined as residue of the lesion. (a) Computed tomography scan shows a multilocular developmental cyst. (b) The post-operative pelvic magnetic resonance imaging of patient No. 9 who suffered from tumour ‘recurrence’ after the surgery. The white arrow shows the residual of a separately lying cyst at the caudal end of the lesion

Eleven patients undertook the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) tests shortly before the surgery. Among them, three had abnormal CEA levels. Two patients of mature teratoma with low-grade mucinous neoplasms had the pre-operative CEA level of 8.73 and 9.49 ng/mL, respectively. In a patient with a teratoma containing the component of mucinous adenocarcinoma, the pre-operative CEA level was 19.18 ng/mL. Her CEA value decreased to 1.35 ng/mL after the surgery.

The average body mass index of the patients was 24.0 ± 4.1. The pure laparoscopic approach was performed in 17 cases (85.0%), including three patients undergoing the prophylactic diverting enterostomy. In three cases, after the laparoscopic surgery, the patient was changed to a jackknife position, and an additional transsacrococcygeal incision was made to complete the dissection of the subcutaneous parts of the lesion. The operating time was 167.1 ± 57.3 min for the pure laparoscopic group and 212.0 ± 24.5 min for the combined laparoscopic-posterior approach group. The intraoperative blood loss of the two groups was 68.2 ± 49.7 and 66.7 ± 28.9 (mL), respectively.

The intraoperative complication included one perforation of coccygeal skin, causing by the laparoscopic dissection too far down to the cutaneous layer, for a lesion presenting with a lump beneath the coccygeal skin. The skin incision was immediately sutured from the bottom during the operation. However, the patient suffered from infection of the residual cavity at the bottom, followed by skin wound infection. Debridement was performed through the bottom skin wound, and the vacuum-assisted closure device (InfoV.A.C. Therapy System, KCI USA, Inc., San Antonio, Texas) was applied. The infectious symptoms relieved soon and the wound healed 3 weeks after the surgery. One patient complicated with the trocar site hernia. A severe complication of delayed rectal wall perforation occurred in one patient (5.0%). The injury was not identified during the surgery, although the digital rectal examination being performed after the tumour removal. The perforation was discovered by the patients’ abnormal fever on the post-operative day 4 and was then confirmed by the water-soluble contrast enema. Emergent surgery of diverting colostomy was performed without repairing the injured rectum. The injury healed spontaneously and the diverting stoma was successfully closed half a year later.

The post-operative hospital stay ranged from 3 to 22 days, with a median of 7 days. With a median follow-up period of 36 (range, 6–64) months, tumour recurrence occurred in one patient (5.0%) [Figure 2b].

DISCUSSION

With the increasing application of imaging studies in the clinical practice or during health checks in recent years, more RTs have been detected incidentally,[9] with RRDCs being the most common type. Most authors believe that these lesions need to be surgically removed once they are diagnosed, even for asymptomatic benign lesions.[9,23]

Due to their embryologic origin, RRDCs are deeply located and have a dense adhesion with the coccyx and the anterior surface of the lower sacrum. In adults, they often grow to a large size and nearly occupy the entire lesser pelvis, penetrating the pelvic floor muscles and even protruding from the sacrococcygeal region.

Conventionally, the posterior approach had been predominantly advocated for RRDCs.[1,17] Glasgow et al.[8] demonstrated that the posterior approach was associated with significantly less intraoperative blood loss, a need for fewer transfusions and less post-operative complications, comparing with laparotomy. One of our previous studies showed that the transabdominal approach is associated with a higher recurrence rate than the posterior approach, due to the difficulties in exposing and dissecting the caudal parts of these deep lesions.[5] Before the laparoscopic approach being employed, large RTs extending cephalad to above the S3 were usually dealt with the more traumatic approach of the composite abdomino-sacrococcygeal route.

In our centre, the laparoscopic approach for RTs was firstly attempted since 2012. Among our more than fifty laparoscopic procedures so far, there was no conversion to open surgery. All the operations were performed by surgeons from the colorectal surgical team. With advantages of the unobstructed and magnified views, and being facilitated by the long instruments, the laparoscopic approach enables access to the entire scope of large RRDCs from the inlet of lesser pelvis to the subcutaneous layer of the coccygeal region, which can hardly accomplished through neither the laparotomy nor the posterior approach. This study demonstrated that the laparoscopic approach can provide a feasible alternative to not only the posterior approach for RRDCs lower than S3 level but also the combined abdomino-sacrococcygeal approach for large spanning cysts that astride the S3 level, with the adequate completeness of tumour removal.

In the meanwhile, the laparoscopic approach provides the benefits of minimally invasive surgery, which includes precise surgical dissection, less traumatic, fewer intraoperative blood loss, faster recovery and better cosmetic results.

Unfortunately, the severe complication of rectal wall injury occurred in one patient with a low-lying lesion penetrating the pelvic floor and strictly adhering to the bare area of the rectum. The late onset of the perforation may be explained by the inadvertent harmonic scalpel burn at the deep and adhering areas, where the surgical exposure and dissection was very difficult. In such condition, careful identification of anatomical structures and meticulous dissection is crucial for the safety of the surgery. Accurately distinguishing the muscular fibres of the rectal wall from those of the levator ani and dissecting by closely clinging to the true capsule of the lesion is very important. Repeated digital rectal examination may aid in the identification and prevent inadvertent injury.[7] In very difficult conditions, however, an additional posterior approach is necessary. In cases with highly suspected rectal wall injury, a prophylactic diverting enterostomy is indicated.

RRDCs are often multilocular lesions with septa. After reviewing the imaging films, we found around two-thirds of the tumours were multilocular. During the follow-up, one tumour recurrence was found at the first imaging recheck 6 months after the surgery. According to the MRI images, the recurred lesion should be more reasonably defined as the residual of a separately lying cyst at the caudal end of the tumour, which might have been missed during the surgery [Figure 2b]. It is therefore recommended for surgeons to carefully read the imaging films before the operation and perform thorough exploration to remove the entire lesion. For lesions, with too distal caudal parts, an additional posterior approach is necessary, as was performed in three cases of the current study.

Large RRDCs often takes too much space in the narrow pelvic cavity, making the dissection of their distal parts very difficult. The procedure can sometimes be facilitated by controlled collapsing the lesion. A small incision is made at the top of the cyst, followed by decompressing, it using the suction apparatus and closing the incision with clips. This can effectively assist in the surgical exposure and the deep dissection. In the current study, 16 cysts (80.0%) were collapsed during the operation. Our results showed that with sufficient lavage of the operative field, the controlled decompression did not increase the perioperative complications. Abel et al. proposed the same viewpoint in their literature.[7]

Although demonstrating potential advantages, the laparoscopic approach is generally indicated only for benign RTs. For RRDCs with malignant degeneration, the validity of the laparoscopic approach has not been assessed. In the current study, one lesion was identified with malignant degeneration. Histological examination revealed a mature teratoma with components of focal mucinous adenocarcinoma [Figure 3]. By reviewing the CT scan, several solid nodules can be identified at the caudal part of the multilocular lesion, which might be the places where the malignant components harboured [Figure 4]. Nevertheless, it is hard to differentiate them from benign nodules merely by the imaging studies. For this patient, we did not anticipate the probability of malignancy before surgery. Postoperatively, the patient was recommended to receive an adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Although having been repeatedly informed the risks of not receiving adjuvant therapy, she did not accept our advice. On the first post-operative rechecks (6 months’ postoperatively) with the CT scan, no disease relapse was identified. Currently, the patient is under close follow-up.

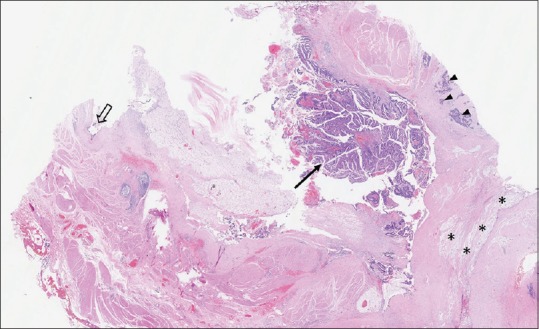

Figure 3.

Medium-power magnification of an H and E-stained section of case No. 20 shows a mature cystic teratoma containing the foci of well-differentiated adenocarcinoma (black arrow) as well as poorly-differentiated mucinous adenocarcinoma (black arrow heads). The black hollow arrow demonstrates the benign columnar epithelium. The black asterisk signs indicate the pool of extracellular mucin

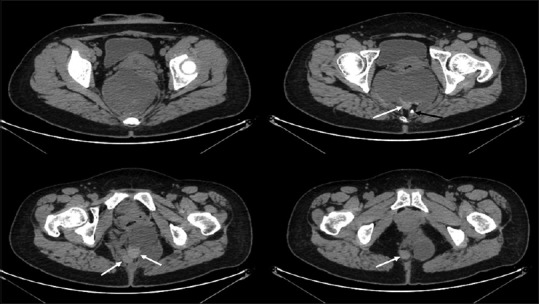

Figure 4.

Computed tomography axial slices at different levels show a retrorectal mature cystic teratoma with focal adenocarcinoma (case No. 20). Several solid nodules locate at the caudal end of the multilocular lesion, which might be the places where the malignant components harbour (white arrows). The black arrow indicates a ‘tooth’ in the mature teratoma

Apart from this case, there were another three cases of mature teratomas with components of low-grade mucinous neoplasms, all being female patients. Among all these four cases with mucinous neoplasms, three underwent the CEA tests before surgery. For the two patients with low-grade mucinous neoplasms, the pre-operative CEA levels increased mildly to 8.73 and 9.49 ng/L, respectively. The patient with mucinous adenocarcinoma had a notably elevated CEA level of 19.2 ng/mL, which decreased to normal after the surgery. In contrast, among the other 16 patients without the mucinous neoplasms, eight had the CEA tests before surgery, all showing the normal results.

According to the above results, we speculate there might be an association between the components of mucinous neoplasm in RRDCs with the increased CEA level. A prominently elevated CEA level may predict the presence of mucinous adenocarcinoma. It is therefore recommended that the CEA level is routinely tested for all the patients with RRDCs before surgery. For cases suspicious for malignancy, a more extensive surgical strategy should be considered. During the operation, the cystic lesion should be kept unruptured. Once ruptured, measures should be taken to prevent spillage of the content of the cyst as far as possible.

The limitation of this study includes its retrospective design that may introduce assessment bias. However, the design was hard to avoid given the rarity of RTs. Nevertheless, the study described the largest series of the laparoscopic approach for large RRDCs within a single centre in the literature to date. Future researches with larger sample size and longer follow-up period, or in the form of a prospective trial, may further evaluate the laparoscopic approach for this disease. Some aspects of the procedure may be further perfected to improve the outcome, reduce the surgical complication and decrease the recurrence rate.

CONCLUSIONS

RTs are rare with RRDCs being the most common type. Conventionally, the posterior approach has been advocated predominantly for RRDCs, with the combined abdomino-sacrococcygeal approach being performed for large lesions extending above S3. The current study shows that the laparoscopic approach may provide a feasible alternative to the conventional approaches for large RRDCs, with adequate completeness of tumour removal and advantages of minimal invasive surgeries. However, for ultralow-lying lesions, especially those strictly adhering to the bare area of the rectal wall, a combined posterior approach may aid in removing the entire lesion more safely.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Uhlig BE, Johnson RL. Presacral tumors and cysts in adults. Dis Colon Rectum. 1975;18:581–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02587141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hobson KG, Ghaemmaghami V, Roe JP, Goodnight JE, Khatri VP. Tumors of the retrorectal space. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1964–74. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jao SW, Beart RW, Jr, Spencer RJ, Reiman HM, Ilstrup DM. Retrorectal tumors Mayo clinic experience, 1960-1979. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:644–52. doi: 10.1007/BF02553440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mccune WS. Management of sacrococcygeal tumors. Ann Surg. 1964;159:911–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-196406000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou JL, Qiu HZ. Management of presacral developmental cysts: experience of 22 cases. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2010;48:284–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woodfield JC, Chalmers AG, Phillips N, Sagar PM. Algorithms for the surgical management of retrorectal tumours. Br J Surg. 2008;95:214–21. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abel ME, Nelson R, Prasad ML, Pearl RK, Orsay CP, Abcarian H, et al. Parasacrococcygeal approach for the resection of retrorectal developmental cysts. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:855–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02555492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glasgow SC, Birnbaum EH, Lowney JK, Fleshman JW, Kodner IJ, Mutch DG, et al. Retrorectal tumors: A diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1581–7. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou JL, Wu B, Xiao Y, Lin GL, Wang WZ, Zhang GN, et al. A laparoscopic approach to benign retrorectal tumors. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:825–33. doi: 10.1007/s10151-014-1146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopper L, Eglinton TW, Wakeman C, Dobbs BR, Dixon L, Frizelle FA, et al. Progress in the management of retrorectal tumours. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18:410–7. doi: 10.1111/codi.13117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singer MA, Cintron JR, Martz JE, Schoetz DJ, Abcarian H. Retrorectal cyst: A rare tumor frequently misdiagnosed. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:880–6. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahan H, Arrivé L, Wendum D, Docou le Pointe H, Djouhri H, Tubiana JM, et al. Retrorectal developmental cysts in adults: Clinical and radiologic-histopathologic review, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Radiographics. 2001;21:575–84. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.21.3.g01ma13575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalady MF, Ludwig KA. Presacral developmental cysts. Semin Colon Rectal Surg. 2004;15:12–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Böhm B, Milsom JW, Fazio VW, Lavery IC, Church JM, Oakley JR, et al. Our approach to the management of congenital presacral tumors in adults. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1993;8:134–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00341185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buchs N, Taylor S, Roche B. The posterior approach for low retrorectal tumors in adults. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:381–5. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0183-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lev-Chelouche D, Gutman M, Goldman G, Even-Sapir E, Meller I, Issakov J, et al. Presacral tumors: A practical classification and treatment of a unique and heterogeneous group of diseases. Surgery. 2003;133:473–8. doi: 10.1067/msy.2003.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cody HS, 3rd, Marcove RC, Quan SH. Malignant retrorectal tumors: 28 years’ experience at memorial sloan-kettering cancer center. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:501–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02604308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharpe LA, Van Oppen DJ. Laparoscopic removal of a benign pelvic retroperitoneal dermoid cyst. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1995;2:223–6. doi: 10.1016/s1074-3804(05)80023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marinello FG, Targarona EM, Luppi CR, Boguña I, Molet J, Trias M, et al. Laparoscopic approach to retrorectal tumors: Review of the literature and report of 4 cases. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21:10–3. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182020e69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nedelcu M, Andreica A, Skalli M, Pirlet I, Guillon F, Nocca D, et al. Laparoscopic approach for retrorectal tumors. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4177–83. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duclos J, Maggiori L, Zappa M, Ferron M, Panis Y. Laparoscopic resection of retrorectal tumors: A feasibility study in 12 consecutive patients. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1223–9. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3312-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Köhler C, Kühne-Heid R, Klemm P, Tozzi R, Schneider A. Resection of presacral ganglioneurofibroma by laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1499. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-4269-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toh JW, Morgan M. Management approach and surgical strategies for retrorectal tumours: A systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18:337–50. doi: 10.1111/codi.13232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]