Abstract

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is one of the most common procedures performed in surgical practice worldwide. Diaphragmatic injury is an extremely rare complication that can occur intraoperatively and needs to be dealt with immediately. This article describes a case report of diaphragmatic injury, technical details of how to deal with this complication and preventive strategies along with a review of literature on the topic.

Keywords: Complication, diaphragmatic injury, intraoperative, laparoscopic cholecystectomy

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is one of the most common procedures performed worldwide and perhaps forms the major portion of work in any general surgical practice. Diaphragmatic injury during LC is extremely rare and has been reported in 2 out of 1748 cases (0.11%)[1] during a 7-year period. Case reports from the 1990s document the existence of this problem.[2] Since then, there have been around twenty odd case reports on this topic. This report describes the occurrence of this complication, discusses reasons, outlines preventive strategies and tips for management.

CASE REPORT

An 80-year-old woman was admitted for interval LC. Past history was significant for acute calculous cholecystitis 2 months ago at which time she was managed conservatively as she was recovering from a stroke. Her performance status was good and she was asymptomatic. On evaluation, ultrasound abdomen revealed multiple gallstones. Gallbladder wall thickness was normal. Liver function tests were normal. She was taken up for LC after informed discussion. Pneumoperitoneum was established by a 10-mm umbilical port inserted by open technique. There was atrophy-hypertrophy complex of the liver (right lobe atrophied) resulting in the gallbladder fossa being located to the right [Figure 1]. A 5-mm epigastric port was placed slightly lower than usual; the conventional right mid-clavicular and anterior axillary ports were moved to the right to facilitate dissection and traction. The last port was used for fundal traction. Omental adhesions were taken down. About 20 min into the procedure, the fundal grasper slipped and went through the right hemidiaphragm causing a 1-cm hole [Figure 2a]. This was recognised immediately and the instrument was withdrawn. There was no lung injury or intra thoracic bleeding. The anaesthetists were alerted to reduce ventilation. The lips of the opening were held together with an atraumatic grasper and a 3.0 polydioxanone figure of 8 suture was taken. Before tightening the suture, a suction was used by the assistant to suck out the pneumothorax and the knot was then secured by the operating surgeon as the suction was withdrawn [Figure 2b]. The patient had normal respiratory mechanics during the rest of surgery and the procedure was completed safely. Post-operative chest radiograph was normal, and she was discharged the following day. She remains well on follow-up.

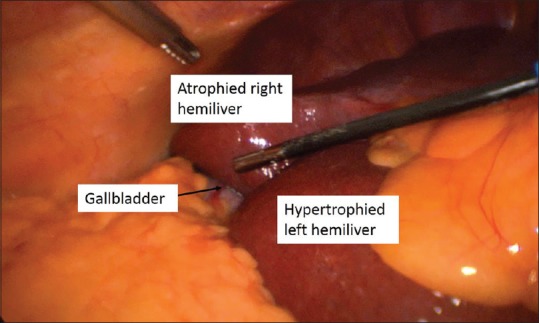

Figure 1.

Atrophy-hypertrophy complex of the liver is seen with the gallbladder (arrow) located far to the right than usual

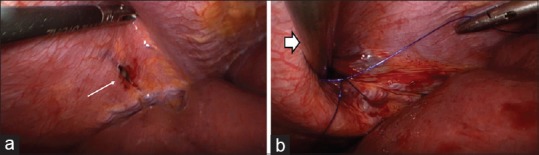

Figure 2.

(a) The rent in the right hemidiaphragm (white arrow). (b) Repair in progress. The bold white arrow depicts the 5-mm suction instrument in the pleural cavity as the suture is being tightened

DISCUSSION

At the authors’ institution, this is the only diaphragmatic injury that has occurred in 1120 LCs (0.09%) done over a period of 4.5 years. Fundal traction during LC is usually delegated to the second assistant or the staff nurse. The direction of traction should be towards the right shoulder and the force just enough to facilitate dissection of the Calot's triangle. In this case, the grasper slipped and the momentum carried the instrument across the diaphragm. Possible reasons for slippage are inadequate tissue in the fundal grasp (improper application/tense gallbladder), dense adhesions that do not permit proper grip/lifting of the liver, a suboptimal instrument which does not lock well, inadvertent opening of the ratchet, use of excessive force or a combination of the above factors. All these are preventable and the entire team should be cognisant of the possibility of a diaphragmatic injury. In this patient, perhaps, the unusual direction of traction on the gallbladder due to atrophy-hypertrophy of the liver may have contributed to slippage of the instrument. The give way was recognised immediately and corrective measures were instituted. It is important to alert the anaesthesia team as the pneumoperitoneum can result in a rapid tension pneumothorax. Since the injury occurs in the most unexpected situation, it is important to have a plan in place and act quickly. In this situation, laparoscopic suturing skills will come in handy. An important technical point to remember is to use a suction to decompress the pleural cavity and withdraw it as the suture is tightened. This will avoid a residual pneumothorax and the need to place an intercostal drain.

Diaphragmatic injuries during LC have also been reported after the use of endoretractors[3] and during single incision LC.[4] This emphasizes the need to pay to attention to every step during surgery. Sometimes, the injury may be missed during surgery and can present in the immediate post-operative period as a tension pneumothorax.[5] Rarely, the patient may present much later with a diaphragmatic hernia and its attendant complications.[6] It is prudent to check the diaphragm whenever a fundal grasper slips. This will prevent missed diaphragmatic injuries. A high index of suspicion is also needed to diagnose complications due to diaphragmatic injury in the post-operative period. This report reiterates the need to follow safe surgical practices at each step and outlines technical details to tackle the problem if it should arise intraoperatively.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Singh R, Kaushik R, Sharma R, Attri AK. Non-biliary mishaps during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2004;23:47–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seiler C, Glättli A, Metzger A, Czerniak A. Injury to the diaphragm and its repair during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:193–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00191964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsiao CY, Wu YM. Diaphragmatic injury caused by an endo-retractor during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Minim Access Surg. 2016;12:73–4. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.158956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hosogi H, Lingohr P, Galetin T, Sakai Y, Saad S. Right diaphragm injury: An unusual complication in single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21:e143–4. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31821a9dbf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aloise F, Rossi EM, Cadregari F, Pastorcich A, Filosa L, Costanzo A, et al. Errors in digestive surgery. A case of tension pneumothorax during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Minerva Chir. 1994;49:841–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouchagier K, Solakis E, Klimopoulos S, Demesticha T, Filippou D, Skandalakis P, et al. A rare case of iatrogenic diaphragm defect following laparoscopic cholecystectomy presented as acute respiratory distress syndrome. Case Rep Surg. 2018;2018:4165842. doi: 10.1155/2018/4165842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]