Abstract

Study objective

We determine the incidence of and trends in enforcement of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) during the past decade.

Methods

We obtained a comprehensive list of all EMTALA investigations conducted between 2005 and 2014 directly from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) through a Freedom of Information Act request. Characteristics of EMTALA investigations and resulting citation for violations during the study period are described.

Results

Between 2005 and 2014, there were 4,772 investigations, of which 2,118 (44%) resulted in citations for EMTALA deficiencies at 1,498 (62%) of 2,417 hospitals investigated. Investigations were conducted at 43% of hospitals with CMS provider agreements, and citations issued at 27%. On average, 9% of hospitals were investigated and 4.3% were cited for EMTALA violation annually. The proportion of hospitals subject to EMTALA investigation decreased from 10.8% to 7.2%, and citations from 5.3% to 3.2%, between 2005 and 2014. There were 3.9 EMTALA investigations and 1.7 citations per million emergency department (ED) visits during the study period.

Conclusion

We report the first national estimates of EMTALA enforcement activities in more than a decade. Although EMTALA investigations and citations were common at the hospital level, they were rare at the ED-visit level. CMS actively pursued EMTALA investigations and issued citations throughout the study period, with half of hospitals subject to EMTALA investigations and a quarter receiving a citation for EMTALA violation, although there was a declining trend in enforcement. Further investigation is needed to determine the effect of EMTALA on access to or quality of emergency care.

INTRODUCTION

Background

In 1986, Congress passed the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) in response to publicized incidents of inadequate, delayed, or denied treatment of uninsured patients by emergency departments (EDs).1,2 The intent of EMTALA was to ensure access to emergency medical services and to prevent patient “dumping,” the practice of refusing or transferring financially disadvantaged patients without authorization or stabilization. EMTALA requires that all patients presenting to an ED receive timely medical screening evaluation and stabilizing care regardless of ability to pay. If specialty services required to stabilize an identified emergency condition are unavailable, patients must be transferred to an alternate hospital for a higher level of care. Receiving hospitals have a duty to accept transfer of patients requiring available specialized services (eg, neurosurgery, burn care) if the facility has capacity to treat the patient.

EMTALA enforcement is delegated to the 10 regional offices of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). CMS regional offices are responsible for authorizing EMTALA investigations, determining whether a violation occurred, and enforcing corrective actions when violations are identified. Hospitals that fail to implement acceptable corrective action plans after an EMTALA violation have their provider agreements terminated by CMS, which has severe financial implications and can ultimately result in facility closure. The Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services is responsible for assigning civil monetary penalties or physician exclusion from CMS participation when EMTALA violations are reported.

Importance

EMTALA is one of the most important pieces of federal legislation specific to the provision of emergency medicine. Despite its importance, there has been relatively little published on EMTALA enforcement activities. The current literature on EMTALA is mostly limited to summaries and interpretations of the EMTALA statute,3–5 reviews of case law,6,7 assessments of patient and provider knowledge about EMTALA,8,9 indirect measures of effect of the statute,10–13 and limited descriptions of EMTALA enforcement before 2001.14–16 We were unable to identify any recent original peer-reviewed longitudinal studies of epidemiology of EMTALA enforcement. To understand the influence of this law on emergency care, it is critical to understand how actively CMS pursues EMTALA enforcement and the characteristics of the incidents for which facilities were cited.

Goals of This Investigation

The goal of this investigation is to describe the incidence, characteristics of, and trends in enforcement of EMTALA during the past decade.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

This is a retrospective study of observational data on EMTALA enforcement activities obtained from CMS. Complaints about potential EMTALA violation can be made by any individual or institution to a state survey agency or CMS regional office. All complaints are forwarded to the designated CMS regional office for review.

In accordance with findings of an initial inquiry, the CMS regional office may authorize an investigation, but state survey agencies are responsible for conducting it.15 Once authorized, an investigation must be completed within 5 working days, and once it is completed, state survey agencies have 10 to 15 working days to provide findings to the CMS regional office.15 State survey agencies investigating EMTALA complaints often review hospital compliance with all aspects of the EMTALA statute (Table E1, available online at http://www.annemergmed.com) and may identify deficiencies unrelated to the specific complaint triggering the investigation. Findings of investigations with actual medical concerns identified (ie, those unrelated to technical components of the statute such as posting of signs) are sent to physicians for review and recommendations. CMS regional offices make the final determination about whether violation of EMTALA has occurred and whether the affected hospital will be cited with an immediate, 23-, or 90-day termination notice. Hospitals failing to implement acceptable corrective action plans to resolve identified deficiencies within the designated timeframes have their CMS provider agreements terminated.

Table E1.

EMTALA deficiency tags and summary of EMTALA interpretive guidelines.1

| Deficiency Tag | Guideline Code, § | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2400 | 489.20(l) | Policies and procedures that address antidumping provisions |

| 2401 | 489.20(m) | Receiving hospitals must report suspected incidences of individuals with an emergency medical condition who are transferred in violation of §489.24(e) |

| 2402 | 489.20(q) | Sign posting |

| 2403 | 489.24(r)(1) | Maintain transfer records for 5 years |

| 2404 | 489.20(r)(2) | Maintenance of on-call list |

| 2404 | 489.24(j) | Availability of on-call physicians |

| 2405 | 489.20(r)(3) | Maintain central log of individuals seeking care in an ED and whether he or she refused treatment, was refused treatment, or was transferred, admitted and treated, stabilized and transferred, or discharged. |

| 2406 | 489.24(a) | Appropriate medical screening examination |

| 2407 | 489.24(d)(1,2,3) | Stabilizing treatment |

| 2408 | 489.24(d)(4) and (5) | No delay in examination or treatment to inquire about payment status |

| 2409 | 489.24(e)(1,2) | Appropriate transfer |

| 2410 | 489.24(e)(3) | Whistle-blower protections |

| 2411 | 489.24(f) | Recipient hospital responsibilities |

We obtained a comprehensive list of all EMTALA investigations conducted between 2005 and 2014 directly from CMS through a Freedom of Information Act request. Our evaluation of EMTALA enforcement starts at the investigation level because allegations of EMTALA violations are not systematically recorded in the absence of an investigation. Although not specifically tracked by CMS, nearly all allegations are authorized by CMS regional offices for investigation (personal communication, Mary Ellen Palowitch, EMTALA Technical Lead, CMS, 2015). The provided data set included the name and location of the hospital and the date of investigation. Additionally, the data included the service type that was alleged to be deficient (medical, trauma, other surgical, labor, other obstetric, or psychiatric) and deficiency type (eg, delay in medical screening examination, inadequate stabilization before transfer). Investigations resulting in a citation for EMTALA violation were identified with CMS’s EMTALA-specific deficiency codes (Table E1, available online at http://www.annemergmed.com). We also observed which citations resulted in termination of CMS provider agreements. For investigations resulting in termination, but for which specific deficiency codes were unavailable in the data set provided, deficiency types were determined according to substantiated allegations for that investigation. Investigations for which completion dates were not available were excluded from analysis. An additional 823 of 5,595 identified investigations (15%) for which survey completion dates were missing were excluded from analysis.

Annual trends in the number of investigations and citations were characterized with descriptive statistics and graphically displayed. The total number of hospitals subject to EMTALA requirements during the study period was estimated by using the number of unique facilities (identified by Medicare provider identification numbers) reporting core measure data between 2005 and 2014 (n=5,594). The annual number of hospitals subject to EMTALA requirements was estimated by identifying the number of unique facilities reporting Medicare core measure data in a given year. Annual estimates of ED visits and ED visits per 1,000 population between 2005 and 2013 were obtained from the American Hospital Association17 and were used to calculate the number of EMTALA investigations and citations per 1 million ED visits. Data from 2014 were unavailable at article submission.

For hospitals with termination of CMS provider agreements, we queried hospital-reported Medicare core measures before and after reported investigation to verify whether facility closure was indicated by cessation of reporting of core measures after the reported citation. Additionally, we conducted an online search to determine whether there was documented evidence of temporary or permanent facility closure after termination of CMS provider agreements. Data were managed with Stata/MP13 (Stata Statistical Software: Release 13; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

We identified 5,594 hospitals with unique CMS provider identification numbers during the study period. Between 2005 and 2014, there were 4,772 completed investigations for EMTALA violations at 2,417 individual hospitals. Of these 4,772 investigations, 2,118 (44%) resulted in citations for EMTALA deficiencies at 1,498 (62%) of the 2,417 hospitals investigated. Ultimately, CMS terminated provider agreements at 12 hospitals cited for EMTALA deficiencies, representing 0.21% of 5,594 hospitals with CMS provider agreements during the study period. Investigations were conducted at approximately 43% of hospitals (2,417 of 5,594), and citations were issued at 27% (1,498 of 5,594) during the study period. During the study period, there were 4.2 investigations and 1.9 citations for EMTALA violation per million ED visits.

EMTALA citations most frequently involved medical emergencies (57%), followed by psychiatric (17%), trauma (12%), other surgical (10%), active labor (9%), and other obstetric-related emergencies (5%). Many investigations resulting in a citation for EMTALA deficiency involved more than 1 service type. For example, among 1,201 citations involving medical emergencies, 167 (14%) involved at least 1 other service type. Additional characteristics of EMTALA citations are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of EMTALA citations and resulting CMS provider agreement terminations, 2005 to 2014.

| EMTALA Citations, n = 2,118 |

CMS Terminations, n = 12 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Citation service category | |||||

| Medical | 1,201 | 57 | 6 | 50 | |

| Psychiatric | 355 | 17 | 4 | 33 | |

| Obstetric | 97 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Labor | 198 | 9 | 2 | 17 | |

| Trauma | 245 | 12 | 0 | 0 | |

| Surgical | 212 | 10 | 0 | 0 | |

| No service type listed | 50 | 2 | 1 | 8 | |

| Deficiency tag and category | |||||

| 2400 | Policies and procedures | 1,547 | 73 | 8 | 67 |

| 2401 | Recipient hospital reporting | 19 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2402 | Sign posting | 211 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| 2403 | Maintenance of transfer records | 64 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 2404 | Physician on-call list and availability | 292 | 14 | 1 | 8 |

| 2405 | Central log | 536 | 25 | 3 | 25 |

| 2406 | Appropriate medical screening exam | 1,163 | 55 | 6 | 50 |

| 2407 | Stabilizing treatment | 526 | 25 | 2 | 17 |

| 2408 | Delay in examination treatment | 108 | 5 | 2 | 17 |

| 2409 | Restricting transfer until stabilized | 589 | 28 | 5 | 42 |

| 2410 | Whistle-blower protections | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2411 | Recipient hospital responsibilities | 335 | 16 | 3 | 25 |

Most hospitals receiving a citation for EMTALA violation were cited for multiple deficiency types. Of hospitals that were cited, most were cited for policies and procedures (73%) (eg, failure of a hospital to adopt and enforce a policy to ensure compliance with EMTALA statutes). Clinical deficiencies associated with citations, including failure to provide an appropriate medical screening examination (55%), failure to stabilize before transfer (28%), and failure to provide appropriate stabilizing treatment (25%), were also common during the study period. Deficiency related to recipient hospital responsibilities were noted in 16% of citations.

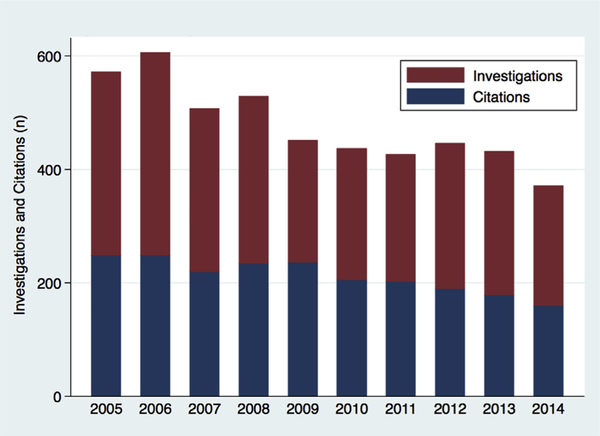

Between 2005 and 2014, there was a decline in EMTALA investigations, from 571 to 371 (a 35% decrease), and also in citations, from 248 to 159 per year (a 40% decrease) (Figure 1). Simultaneously, the number of hospitals with investigations decreased from 469 to 353 (a 25% decrease), whereas the number of hospitals receiving citations decreased from 232 to 154 per year (a 34% decrease). The proportion of investigations resulting in citations remained stable throughout the study period and was 43% both in 2005 and 2014. The annual number of hospitals with unique CMS provider identification numbers increased from 4,354 in 2005 to 4,875 in 2014.

Figure 1.

Investigations and citations for EMTALA violation, 2005 to 2014.

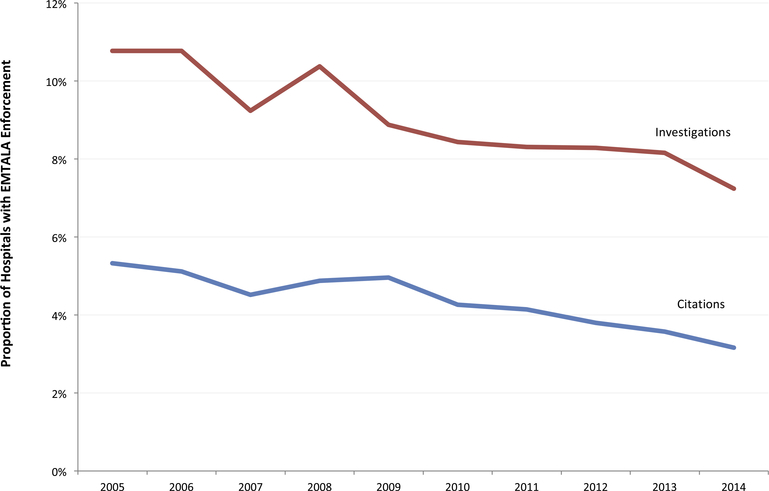

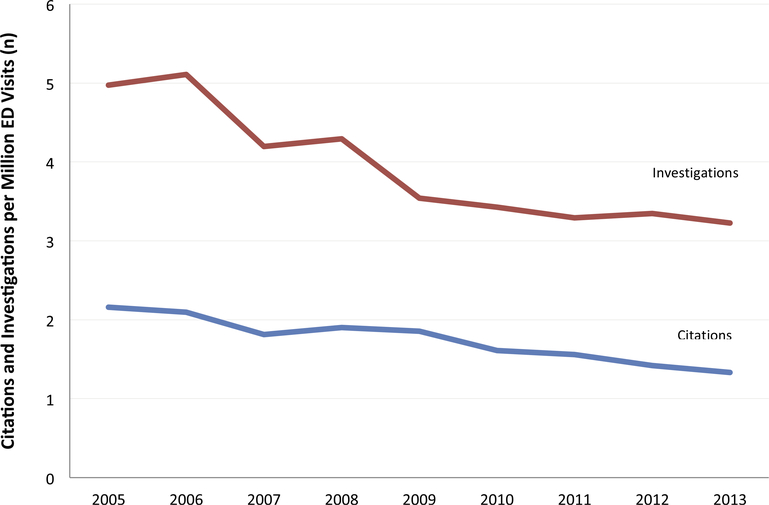

On average during the study period, 9.0% of hospitals were investigated in a given year, and 4.3% were cited for EMTALA violation. Figure 2 depicts the proportion of hospitals with an EMTALA investigation or citation during the study period. Between 2005 and 2014, the proportion of hospitals with an EMTALA investigation decreased from 10.8% to 7.2% (32%), and the proportion with EMTALA citations decreased by 41%, from 5.3% to 3.2%. Between 2005 and 2013 (years for which American Hospital Association ED visit data were available), the annual rate of EMTALA investigations declined by 36%, from 5.0 to 3.2 per million ED visits, whereas citations decreased by 38%, from 2.1 to 1.3 (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Proportion of hospitals with EMTALA investigations and citations, 2005 to 2014.

Figure 3.

EMTALA investigations and citations per million ED visits, 2005 to 2013.

Characteristics of EMTALA citations by service and deficiency types in 2005 and 2014 are included in Table 2. During the decade-long study period, the proportion of EMTALA citations related to medical emergencies increased from 52% to 60%, and the proportion related to psychiatric emergencies increased from 18% to 20%. A decrease in the proportion of EMTALA citations attributable to obstetric (5% to 3%), labor (13% to 11%) and trauma (10% to 9%), and other surgical emergencies (17% to 7%) was observed during the same period.

Table 2.

Characteristics of EMTALA citations by service type and deficiency in 2005 and 2014.

| Year |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | 2005 | 2014 | |||

| EMTALA citations (n) | 248 | 159 | |||

| Hospitals cited (n) | 232 | 154 | |||

| Citation service category | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Medical | 130 | 52 | 96 | 60 | |

| Psychiatric | 45 | 18 | 32 | 20 | |

| Obstetric | 13 | 5 | 5 | 3 | |

| Labor | 32 | 13 | 17 | 11 | |

| Trauma | 25 | 10 | 14 | 9 | |

| Surgical | 41 | 17 | 11 | 7 | |

| No service type listed | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| Allegation subtypes | |||||

| 2400 | Policies and procedures | 163 | 66 | 121 | 76 |

| 2401 | Recipient hospital reporting | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 2402 | Sign posting | 23 | 9 | 15 | 9 |

| 2403 | Maintenance of transfer records | 8 | 3 | 5 | 3 |

| 2404 | Physician on-call list and availability | 38 | 15 | 20 | 13 |

| 2405 | Central log | 74 | 30 | 38 | 24 |

| 2406 | Appropriate medical screening exam | 132 | 53 | 96 | 60 |

| 2407 | Stabilizing treatment | 65 | 26 | 29 | 18 |

| 2408 | Delay in examination or treatment | 16 | 6 | 11 | 7 |

| 2409 | Restricting transfer until stabilized | 64 | 26 | 51 | 32 |

| 2410 | Whistle-blower protections | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2411 | Recipient hospital responsibilities | 51 | 21 | 15 | 9 |

Between 2005 and 2014, the proportion of citations related to general policies and procedures increased from 66% to 76%, whereas the proportion of citations related to maintenance of a central log decreased from 30% to 24%, and those related to maintenance of a physician-on-call list decreased from 15% to 13%.

The proportion of citations related to provision of appropriate medical screening examination increased from 52% to 60%, and the citations related to restricting transfer until a patient is stabilized increased from 26% to 32%.

During the study period, CMS terminated provider agreements at 12 hospitals as a result of EMTALA citations. One public safety-net facility in Los Angeles County had 3 separate investigations (1 in 2006 and 2 in 2007), for which the outcome was CMS provider agreement termination and ultimately facility closure. Information for all 3 citations for this facility was combined and reported as a single citation/termination. Characteristics of investigations resulting in a citation and CMS provider agreement termination are included in Table 1. Categories associated with EMTALA citations resulting in termination included 6 medical- (50%), 4 psychiatric- (33%), and 2 labor-related services (17%). One hospital was cited for both labor- and medical-related emergencies, and another had no clinical category assigned. Six of 12 terminations (50%) occurred in 2007, and no terminations were identified after 2012. All citations resulting in facility termination notices occurred within 3 CMS regions (IV, VI, and IX). According to a review of available news and other Internet sources, it appears that termination of CMS provider agreement resulted in at least temporary facility closure and or downgrading of emergency services at 9 of the 12 facilities (75%). Facility closure was additionally verified by review of CMS core measures, which for all 9 facilities identified as having been closed were reported before CMS provider agreement termination and ceased to be reported after termination.

LIMITATIONS

Although this study is the most comprehensive assessment of EMTALA enforcement to date to our knowledge, there are several potential limitations. First, the reported findings depended on administrative data provided by CMS. Therefore, our findings may have been limited by coding inconsistencies inherent to secondary data analysis. However, there is no reason to believe that there was any systematic error in recording of data fields by CMS regional offices.

Second, it is possible that not all investigations or citations are included in the data set provided. We believe that the information obtained from CMS through the Freedom of Information Act request represents the best available data source to study EMTALA enforcement.

Third, our evaluation of EMTALA enforcement started at the level of the investigation rather than the allegation. Because allegations of EMTALA violations are not systematically recorded in the absence of an investigation, thorough evaluation of complaints not resulting in authorized investigations was not possible. However, whereas EMTALA investigations have tremendous influence on hospitals, CMS does not routinely inform hospitals of EMTALA allegations not resulting in investigation, and therefore allegations of EMTALA violation without resulting investigations are unlikely to change practice.

Fourth, available data did not include descriptions of the plans for corrective action, and we were therefore unable to evaluate how hospitals allocated resources in response to EMTALA investigations and citations or the associated costs. Fifth, our evaluation of EMTALA was limited to the past decade, the years for which CMS has maintained electronic records of EMTALA enforcement. To better understand trends in EMTALA enforcement during the first 2 decades of EMTALA enforcement, hard copies of historic nonelectronic documents need to be obtained and abstracted. Finally, the present study did not assess the effect of EMTALA on patient care.

DISCUSSION

Passed by Congress in 1986, EMTALA was landmark legislation aimed at improving access to and quality of emergency care. To our knowledge, we report the first peer-reviewed longitudinal description of trends in EMTALA enforcement activities. Although EMTALA citations were rare on the ED-visit level, with 1.7 per million ED visits, we found that citations were common at the facility level. In the past decade, investigations occurred at nearly half of hospitals with Medicare provider agreements, and more than a quarter of hospitals received citations for EMTALA violations.

Faced with the threat of CMS provider agreement termination, facilities investigated or cited for EMTALA violation must respond quickly and aggressively and may overcompensate to avoid hospital closure. Facilities have only 23 to 90 days to execute corrective actions, an extremely challenging timeframe in which to implement the types of changes needed to avoid provider agreement termination (eg, recruiting, hiring, and credentialing additional staff to avoid future delays in examination). Although specific costs have not been reported, rapidly implementing these types of corrective actions to EMTALA citations could be incredibly costly. Hospitals that hire additional staff as part of their corrective action plan face incurring not only the expense at hire but also the costs associated with maintaining additional staffing in perpetuity. Evaluation of hospital response to an investigation or citation and associated costs are prime areas for future research.

Although there were 2,118 citations for EMTALA violation issued during the study period, only 12 hospitals ultimately had provider agreements terminated by CMS. These terminations were important because the majority resulted in facility closure, undoubtedly a powerful motivator for other hospitals to aggressively respond to EMTALA citations. The majority of hospitals cited for EMTALA violation were able to successfully implement appropriate corrective actions, thereby avoiding CMS provider agreement terminations. Although corrective actions to improve EMTALA compliance are costly and burdensome to hospitals, our findings suggest that they are almost always achievable and that an investigation or citation might be required to motivate facilities to implement these measures to achieve compliance. Half of CMS provider agreement terminations occurred in 2007, and terminations have been relatively rare since then. The relatively rarity of terminations after their upswing in 2007 may represent increased awareness by hospital administrators of consequences of EMTALA enforcement and resulting improved compliance with the law. Alternately, the decline in terminations since 2007 may reflect diminishing enforcement efforts by CMS.

For emergency physicians, a civil monetary fine is one of the most feared consequences of an EMTALA citation because physicians may be held individually liable, and this fine is not covered by malpractice insurance. CMS regional offices forward cases of citations for EMTALA violation to the Office of the Inspector General, which has the power to assign civil monetary penalties of up to $50,000 to hospitals or individual physicians and can exclude physicians from future participation in the Medicare program.15 Previously published reports show that between 1995 and 2000, the Office of the Inspector General imposed fines on 194 hospitals and 19 physicians, totaling $5.6 million, and from 2002 to 2012,14 the office filed 160 monetary penalties, 6 of which were assessed to individual physicians.18 There were on average approximately 21 Office of the Inspector General penalties to facilities and only 1.5 fines to individual physicians annually during the years reported. In comparison, between 2005 and 2014, we found an average of 477 investigations and 212 citations for EMTALA violation annually. Monetary penalties assessed by the Office of the Inspector General are rare at the hospital level and almost negligible at the physician level. Fewer than 1 in 10 citations for EMTALA violation results in monetary penalties to facilities, and less than 1% of EMTALA citations result in assignment of monetary fines to individual physicians.

The comparative risk of a malpractice claim highlights the relative rarity of an EMTALA penalty’s being imposed on an individual physician. Annually, 7.6% of emergency physicians face a malpractice claim, and 1.4% have a claim resulting in payment to a plaintiff.19 In comparison, only 1 or 2 physicians in the country are subject to individual monetary penalties by the Office of the Inspector General in a given year. Of 5 civil monetary penalties assigned to individual providers between 2002 and 2007, 3 were assigned to obstetricians and 2 to on-call surgical specialists; none were assigned to emergency physicians.20 Because civil monetary penalties assigned to individual physicians appear to primarily target on-call obstetricians and surgical specialists rather than emergency physicians, risk of monetary penalty to an individual emergency physician appears to be exceedingly low.

Between 2005 and 2013, ED visits in the United States increased in number (from 114.8 to 133.6 million) and rate (from 388 to 423 per 1,000).17 During the same period, the number of hospitals with CMS provider agreements increased from 4,354 to 4,875, but the number of EDs decreased from 4,611 to 4,440.17 We identified a trend toward fewer EMTALA investigations and citations during the past decade. EDs are being visited by more patients, thereby incurring opportunities for possible EMTALA complaints; however, there were actually fewer EMTALA investigations and citations per capita and per hospital over time. We are left with the question of whether the observed temporal decline in EMTALA enforcement despite increasing numbers of ED visits reflects improved hospital compliance with administrative components of the statute, diminished enforcement efforts by CMS, or improvement in access to or quality of emergency care.

We found that many EMTALA investigations and citations involve administrative components of the law (eg, policies and procedures). Citations for some administrative categories of EMTALA deficiencies (eg, maintenance of central log, maintenance of physician on-call list) decreased during the study period, suggesting that hospitals may be improving their ability to comply with nonclinical aspects of the law. However, citations for important EMTALA deficiencies pertaining specifically to patient care were common during the study period. Citations for provision of appropriate medical screening examinations and restricting transfer until a patient is stabilized actually increased as a proportion of all citations during the study period, raising questions about whether EMTALA actually accomplished its original goals of reducing patient dumping or improving access to quality emergency care.

Officials investigating EMTALA complaints typically review hospital compliance with all aspects of the EMTALA statute, often identifying additional deficiencies unrelated to the specific complaint that triggered the investigation. A summary of findings from a 2009 EMTALA investigation at an Arizona hospital is provided as an example in Table E2 (available online at http://www.annemergmed.com). This investigation was initiated after a 69-year-old woman presenting with an ear laceration was reportedly encouraged by a physician at triage to seek care at another facility because plastic surgery was unavailable at the ED. Investigators found that this patient was not triaged or assessed for her injuries by the ED. Using observation, interview, and review of 20 patient records, investigators identified and cited the facility for a variety of administrative and clinical EMTALA deficiencies both related and unrelated to the case for which the investigation was initiated, including failure to provide appropriate medical screening examination, arrange appropriate transfer, maintain a log of all patients presenting to the ED for evaluation, and post appropriate signage. This case highlights how EMTALA citations may be issued in absence of an adverse outcome when the letter of the law has been disregarded, in contrast with malpractice, for which damages must be established.

Table E2.

Examples of deficiencies identified during an EMTALA investigation in Arizona, 2009.

| Deficiency Tag | Description of Identified Deficiencies | Summary of Case and Investigation Findings |

|---|---|---|

| 2400 | Policies and procedures that address antidumping provisions | This EMTALA investigation was initiated after a 69-year-old woman presented to an ED after a fall at home with a laceration to her ear. A physician at triage reportedly stated that the patient could not be treated at the ED because she may need plastic surgery and encouraged her family to transport her by private vehicle to another facility for care. The patient was not triaged or assessed for pain from her injuries. The family transported the patient to the receiving hospital. |

| 2402 | Sign posting | According to observation and interview, the facility failed to post signs conspicuously in any ED or in a place or places likely to be noticed by all individuals entering the ED, as well as individuals waiting for examination and treatment in other areas. |

| 2405 | Maintenance of central log | According to interview and document review, the hospital failed to maintain a central log on each individual presenting to the ED seeking assistance, and whether he or she refused treatment, was refused treatment, or was transferred, admitted and treated, stabilized and transferred, or discharged. Investigators identified that 3 of 20 cases reviewed had no disposition documented. The hospital was found not to have a policy about log maintenance. |

| 2406 | Medical screening examination | According to interview and record review, the hospital failed to provide and document appropriate medical screening examination within the capability of the hospital’s ED for 6 of 20 sampled patients, including the 69-year-old patient presenting with an ear laceration described above. In regard to the described patient, there was no record of refusal of examination or treatment form. |

| 2409 | Appropriate transfer | According to interview and record review, hospital failed to provide appropriate transfer to 3 of 20 sampled patients. Examples include a patient who presented to the ED after a motorcycle crash, was noted to have an emergency medical condition, and was transferred to another facility. Investigators found that in this case, there was no documentation that a copy of the patient’s medical record went with the patient. |

Initially intended as an antidumping law, EMTALA was established to prevent EDs from refusing or transferring uninsured or otherwise financially disadvantaged patients without authorization or stabilization. Whether EMTALA has effectively improved access to or quality of emergency care is an important policy question that remains to be answered. There is some indirect evidence to suggest that it may have a paradoxic effect on access to emergency services. For example, previous research suggests that since passage of EMTALA, erosion of on-call panels and the ability to transfer for higher level of care appear to have worsened.10,13

However, the health care landscape has changed significantly in the past few years. Since 2014, approximately 16.4 million previously uninsured persons have gained health care coverage through Medicaid expansion and other provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.21 Theoretically, this should result in a decrease in patient dumping and increased access to quality emergency care. Looking forward, trends in EMTALA enforcement may yield insight into the effect of insurance expansion on patient dumping and access to emergency care.

CMS actively pursued EMTALA investigations and issued citations throughout the study period, with nearly half of hospitals subject to EMTALA investigations and more than a quarter receiving a citation for EMTALA violation. Whether EMTALA enforcement serves as a feasible mechanism to change hospital behavior and improve access to or quality of care remains to be determined. Unfortunately, presently no reliable measurement is available to determine how successful EMTALA has been at reducing patient dumping or improving access to care. Although EMTALA citations resulting in termination of CMS contracts typically result in closure of EDs and on occasion entire medical facilities, the effect of EMTALA citations on the many facilities that remain open does not appear to have been previously studied. Further work is needed to examine the effect of EMTALA enforcement on access to and quality of emergency care at institutions investigated and cited for EMTALA violations.

Editor’s Capsule Summary.

What is already known on this topic

The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) requires that all emergency department patients receive a medical screening examination and stabilization regardless of ability to pay. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services investigate and cite hospitals for violations.

What question this study addressed

How often, and why, are hospitals investigated and cited for EMTALA violations?

What this study adds to our knowledge

During the last decade, approximately 9.0% of hospitals were investigated and 4.3% were cited annually. Citations are decreasing overall, but violations for medical emergencies, psychiatric emergencies, failure to provide a medical screening examination, and restricting transfer to stabilize patients are increasing in proportion.

How this is relevant to clinical practice

These data show that violations related to administrative (nonclinical) components of the law are decreasing in proportion but that those related to clinical components may be increasing in proportion.

Acknowledgments

Funding and support: By Annals policy, all authors are required to disclose any and all commercial, financial, and other relationships in any way related to the subject of this article as per ICMJE conflict of interest guidelines (see www.icmje.org). The authors have stated that no such relationships exist. An F32 Individual Postdoctoral Award supported Dr. Terp’s time (AHRQF32 HS02240201).

Contributor Information

Sophie Terp, Department of Emergency Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA; Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA.

Seth A. Seabury, Department of Emergency Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA; Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA.

Sanjay Arora, Department of Emergency Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA; Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA.

Andrew Eads, Department of Emergency Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA.

Chun Nok Lam, Department of Emergency Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA.

Michael Menchine, Department of Emergency Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA; Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ansell DA, Schiff RL. Patient dumping. Status, implications, and policy recommendations. JAMA. 1987;257:1500–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiff RL, Ansell DA, Schlosser JE, et al. Transfers to a public hospital. A prospective study of 467 patients. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:552–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenbaum S The enduring role of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:2075–2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West JC. EMTALA obligations for psychiatric patients. J Healthc Risk Manag. 2014;34:5–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zibulewsky J The Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA): what it is and what it means for physicians. Proceedings. 2001;14:339–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindor RA, Campbell RL, Pines JM, et al. EMTALA and patients with psychiatric emergencies: a review of relevant case law. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64:439–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenbaum S, Cartwright-Smith L, Hirsh J, et al. Case studies at Denver Health: “patient dumping” in the emergency department despite EMTALA, the law that banned it. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:1749–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonnell WM, Roosevelt GE, Bothner JP. Deficits in EMTALA knowledge among pediatric physicians. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:555–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonnell WM, Gee CA, Mecham N, et al. Does the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act affect emergency department use? J Emerg Med. 2013;44:209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American College of Emergency Physicians. On-call specialist coverage in U.S. emergency departments: ACEP survey of emergency department directors. 2004. Available at: https://www.acep.org/clinical—practice-management/on-call-specialty-shortage-resources. Accessed October 15, 2015.

- 11.McConnell KJ, Johnson LA, Arab N, et al. The on-call crisis: a statewide assessment of the costs of providing on-call specialist coverage. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:727–733; 733.e721–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McConnell KJ, Newgard CD, Lee R. Changes in the cost and management of emergency department on-call coverage: evidence from a longitudinal statewide survey. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52:635–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menchine MD, Baraff LJ. On-call specialists and higher level of care transfers in California emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.United States General Accounting Office. EMTALA implementation and enforcement issues. June 2001. Available at: http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d01747.pdf. Accessed August 15, 2015.

- 15.US Department of Health & Human Services: Office of Inspector General. The emergency medical treatment and labor act: the enforcement process. January 2001. Available at: http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-09-98-00221.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ballard DW, Derlet RW, Rich BA, et al. EMTALA, two decades later: a descriptive review of fiscal year 2000 violations. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Hospital Association. Table 3.3: Emergency department visits, emergency department visits per 1,000 and number of emergency departments, 1993–2013. 2015. Available at: http://www.aha.org/research/reports/tw/chartbook/2015/table3-3.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2015.

- 18.Raffetto BEA, Burner E, Menchine M. Trends in EMTALA violations from 2002–2012. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20(Suppl):S88. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, et al. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:629–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Department of Health and Human Services: Office of Inspector General. Patient dumping. Available at: http://oig.hhs.gov/reportsand-publications/archives/enforcement/patient_dumping_archive.asp. Accessed October 15, 2015.

- 21.US Department of Health & Human Services. Health insurance coverage and the affordable care act. May 5, 2015. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-report/health-insurance-coverage-andaffordable-care-act. [Google Scholar]

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Revisions to Appendix V, “Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) Interpretive Guidelines.”. May 29, 2009. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Transmittals/downloads/R46SOMA.pdf.