Abstract

Objective

Emerging evidence suggests potential positive neuropsychological effects of periconceptional folate in both healthy children and children exposed in utero to antiseizure medications (ASMs). In this report, we test the hypothesis that periconceptional folate improves neurodevelopment in children of women with epilepsy by re-examining data from the Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (NEAD) study.

Methods

The NEAD study was an NIH-funded, prospective, observational, multicenter investigation of pregnancy outcomes in 311 children of 305 women with epilepsy treated with ASM monotherapy. Missing data points were imputed with Markov chain Monte Carlo methods. Multivariate analyses adjusted for multiple factors (e.g., maternal IQ, ASM type, standardized ASM dose, and gestational birth age) were performed to assess the effects of periconceptional folate on cognitive outcomes (i.e., Full Scale Intelligence Quotient [FSIQ], Verbal and Nonverbal indexes, and Expressive and Receptive Language indexes at 3 and 6 years of age, and executive function and memory function at 6 years of age).

Results

Periconceptional folate was associated with higher FSIQ at both 3 and 6 years of age. Significant effects for other measures included Nonverbal Index, Expressive Language Index, and Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment Executive Function at 6 years of age, and Verbal Index and Receptive Language Index at 3 years of age. Nonsignificant effects included Verbal Index, Receptive Index, Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function–Parent Questionnaire Executive Function, and General Memory Index at 6 years of age, and Nonverbal Index and Expressive Index at 3 years of age.

Conclusions

Use of periconceptional folate in pregnant women with epilepsy taking ASMs is associated with better cognitive development.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier:

In the general population, folate supplementation is recommended for all women of childbearing potential to prevent birth defects (i.e., spina bifida)1 and may improve cognitive and behavioral neurodevelopmental outcomes.2–9 Antiseizure medications (ASMs) can produce both anatomic and neurodevelopmental deficits, although the risks vary across ASMs.10 Two large studies have not found evidence that periconceptional folic acid supplementation can reduce ASM-associated malformations,11,12 but 2 recent publications from the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort study suggest that periconceptional folate may have a protective effect against fetal ASM-induced language delay and autistic traits on the basis of validated maternal surveys with fetal ASM exposure.13,14 However, some prior studies have not found an effect of periconceptual folate in children of women who took ASMs during pregnancy.15,16

We previously reported from our Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (NEAD) study based on blinded objective neuropsychological testing that periconceptional folate in children with fetal ASM exposure was associated with increased Full Scale Intelligence Quotient (FSIQ) at 3 and 6 years of age, increased Verbal Index score at 3 years of age, reduced Behavior Assessment System for Children parent ratings of somatization and atypicality, and reduced Behavior Assessment System for Children teacher ratings of anxiety.17–20 However, given that our prior publications were focused on differential ASM effects, many aspects of the neuropsychological battery in regard to folate were not published. In this present report, we extend our investigation to explore the relationship of periconceptional folate exposure to cognitive development across the multiple measures from the detailed formal neuropsychological evaluations in children with fetal ASM exposure from the NEAD study.

Methods

Design

The NEAD study was a prospective observational investigation with blinded cognitive assessment. Pregnant women with epilepsy on ASM monotherapies (i.e., carbamazepine, lamotrigine, phenytoin, or valproate) were enrolled (October 1999–February 2004) across 25 epilepsy centers in the United States and United Kingdom (Appendix 2 provides a list of individual centers). No other AMSs were used in adequate numbers to assess. A nonexposed control group was not included because the NIH review panel unanimously recommended deletion from our original design.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The study is registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT00021866. The Institutional Review Board at each site approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained according to the Declaration of Helsinki. An NIH-appointed Data Safety Monitoring Board monitored study conduct.

Participants

Women with an IQ < 70 were excluded to avoid floor effects because maternal IQ is the major predictor of child IQ.21 Other exclusions included positive syphilis or HIV serology, progressive cerebral disease, other major disease (e.g., diabetes mellitus), exposure to known teratogenic agents other than ASMs, poor ASM compliance, drug abuse in the prior year, or drug abuse sequelae.

Procedures

Potentially confounding variables were assessed (e.g., maternal IQ, age, education, employment, race/ethnicity, seizure/epilepsy types and frequency, ASM doses, compliance, medical history, socioeconomic status, UK/US site, concomitant medications, alcohol, tobacco, or other drugs during pregnancy, unwanted pregnancy, abnormalities/complications in present or prior pregnancies, enrollment and birth gestational ages, birth weight, breastfeeding, and childhood medical diseases). Abnormalities/complications in prior and present pregnancies included miscarriages, malformations, and obstetrical complications such as caesarian sections or hemorrhage. Adherence for periconceptional folate and other medications before enrollment was collected retrospectively by mother report (the average gestational age at enrollment was 18 weeks, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 17–19). Adherence for all medicines and vitamins, including folate after enrollment, was collected prospectively by mother report. Periconception folate and pregnancy folate were collected as potentially confounding variables in the NEAD study, but periconceptional folate is the primary issue in the present analyses. Periconceptional folate exposure was determined retrospectively at the time of enrollment by report of the mother. She was classified as taking periconceptional folate if she reported taking folate ≥1 month before conception. The folate dose at conception was used for analyses. Periconceptional folate was categorized as to daily dose of 0, >0.0 to 0.4, >0.0.4 to 1.0, >1.0 to 4.0, and >4.0 mg. Except for maternal IQ, variables were collected from the mothers, their seizure/medication diary, or medical record review. Compliance for ASMs was assessed by interviewing all mothers and reviewing diaries and ASM levels (75% of mothers, n = 229). Blinded neuropsychological assessors evaluated cognitive outcomes. Neuropsychological examiners were trained and monitored to ensure quality. Annual workshops were conducted, and assessors were asked to identified errors and corrections for videotaped test sessions containing administration/scoring errors. In addition, the neuropsychology core director reviewed and approved videotapes of assessor practice test sessions and record forms. If failed, assessors were required to submit additional videotaped practice assessments.

Further details of the neuropsychological tests are offered elsewhere.17–19 Evaluations of cognitive outcomes included the Differential Ability Scales (DAS)22 at 3, 4.5, and 6 years of age. At 3 years of age, testing also included the Preschool Language Scale–4th Edition (PLS-4),23 the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test–4th Edition (PPVT-4),24 and the Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration–5th Edition (DTVMI-5).25 Testing at 6 years of age also included the core battery of the Children's Memory Scale,26 the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function–Parent Questionnaire (BRIEF),27 selected subtests from the Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment (NEPSY),28 the Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test,29 and the DTVMI-5.25

From the NEAD neuropsychological batteries, the primary a priori dependent variables included the General Conceptual Ability score from the DAS at 6 years of age, which is similar to the FSIQ score from the Wechsler Full Scale Intelligence Scales. In addition, we constructed Verbal and Nonverbal indexes and subcomponents of language using Expressive and Receptive Language indexes from both the 3- and 6-year assessments to examine components of language and other cognitive functions. Other dependent variables at 6 years of age included the Children's Memory Scale General Memory Score, the NEPSY Executive Function Score, and the BRIEF Global Executive Composite Score.

The Verbal Index score from the 3-year assessment was created by averaging the Expressive Communication and the Auditory Comprehension subtest scores of the PLS-4,23 the Naming Vocabulary and the Verbal Comprehension subtest scores of the DAS,22 and the score from the PPVT-4.24 The Nonverbal Index score was the average of the scores from the Block Building subtest of the DAS22 and the DTVMI-5.25

The Verbal Index score from the 6-year assessment was created by averaging the scores from the Word Definitions and Verbal Similarities subtests from the DAS,22 the Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test,29 and the Phonological Processing, Comprehension of Instructions, and Sentence Repetition subtests from the NEPSY-2.28 The Nonverbal Index was the average of the scores from Pattern Construction, Matrices, and Recall of Designs recall subtests of the DAS,22 the Arrows subtest from the NEPSY-2,28 and the DTVMI-5.25

At age 3, the Expressive Language Index comprised the Expressive Communication score from the PLS-423 and the Naming Vocabulary subtest from the DAS.22 The Receptive Language Index comprised the Auditory Comprehension score from the PLS-4,23 the PPVT-4,24 and the Verbal Comprehension score from the DAS.22 At age 6, the Expressive Language Index was made up of the Word Definitions and Similarities scores from the DAS,22 the Expressive One Word Picture Vocabulary Test,29 and the Verbal Fluency from the NEPSY.28 The Receptive Language Index comprised the Comprehension of Instructions, Sentence Repetition, and Phonological Processing subtest scores from the NEPSY.28

Statistical analysis

Sample sizes were determined for 80% power to detect a 0.5-SD IQ difference, a clinically meaningful difference observed in prior studies.10 The approach to analyses was similar to our prior publications on the NEAD study.17–19 The primary analysis used linear regression models with ASM and periconceptual folate as the main predictors of interest. All models were also adjusted for maternal IQ and standard dose (same as previous analyses). Additional covariates examined were maternal age, gestation age at birth, race/ethnicity, maternal education, epilepsy/seizure types, employment, socioeconomic status, US/UK site, alcohol/tobacco use, and unwanted pregnancy. Because specific ASM, ASM dose, and maternal IQ are important covariates, they were included as predictors in all linear models, along with periconceptional folate as the main predictor of interest and child cognitive measures as outcomes. Other covariates were selected into the model with a forward selection algorithm. Starting with a model including ASM, dose, maternal IQ, and folate, each additional covariate was individually assessed, and the covariate with the largest F statistic, provided that p < 0.5, was selected into the model. This process continued until no additional covariates were significant (p < 0.5) when added to the model. The forward selection algorithm was applied to the total enrolled analysis dataset, and the same covariates selected for that model were used for the completers analysis. Diagnostic plots were inspected to ensure that distributional assumptions of the models were met. For the total enrolled analysis, Markov chain Monte Carlo methods30,31 were used to impute missing age 6 or age 6 outcomes from available age 2, 3, and 4.5 IQs, baseline variables related to outcome, likelihood of missing data, and other additional covariates assessed for inclusion in the final models. As detailed previously,19 the number of completers at each age was 187 at 2 years, 230 at 3 years, 209 at 4.5 years, and 225 at 6 years. The imputation procedure generated 50 imputed datasets and fitted regression models to each. Regression parameter estimates were combined across imputations with standard errors that incorporated imputation uncertainty. Mothers of children with missing age 6 outcomes differed on maternal age and US/UK site (imputation model included these variables). Standard errors and CIs of parameter estimates incorporated imputation uncertainty. Intent-to-treat (ITT) analyses for age 6 were considered the primary analyses here. Secondary analyses for age 3 ITT and for age 3 and 6 completers without imputations for missing data were conducted. Analyses were performed at the NEAD Data and Statistical Center with SAS 9.4 and R statistical software. A major goal of the present study was to conduct exploratory comparisons across a variety of cognitive domains. In this context, we felt it was more important to avoid type 2 errors, so we did not correct for multiple comparisons.

Data availability

All data included in these analyses will be shared as anonymized data via request from any qualified investigator.

Results

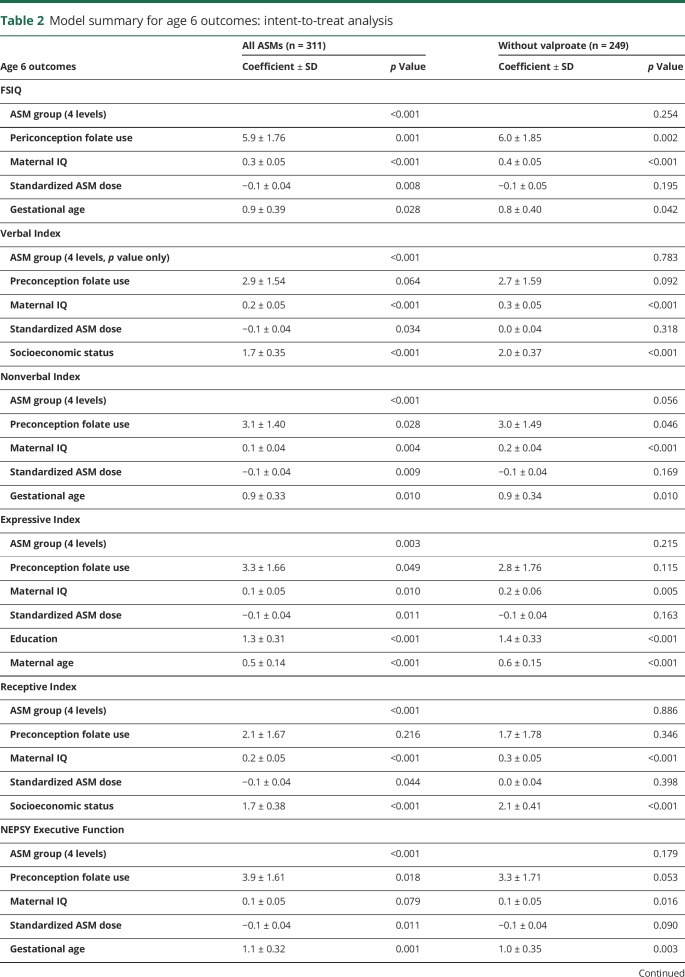

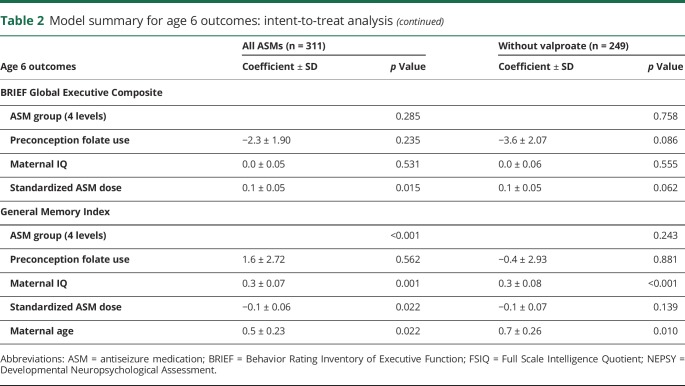

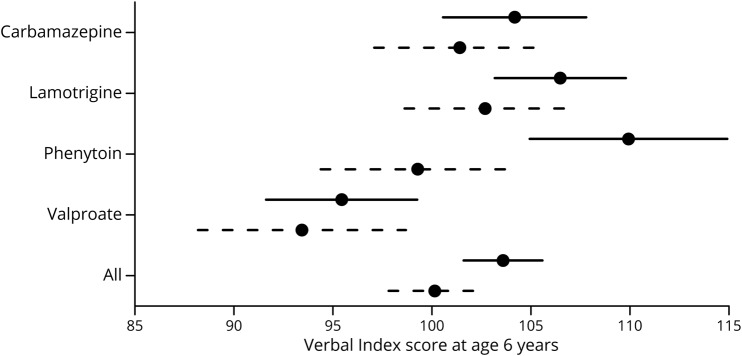

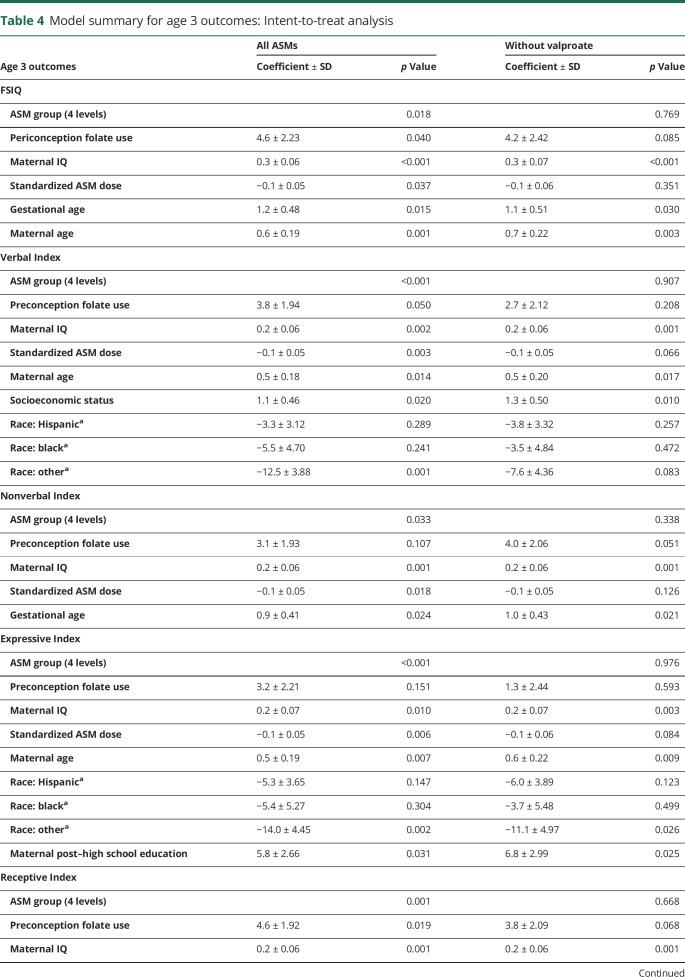

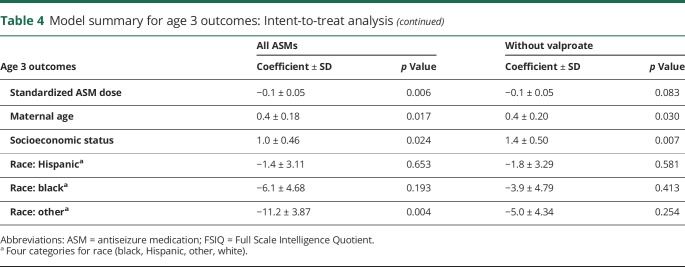

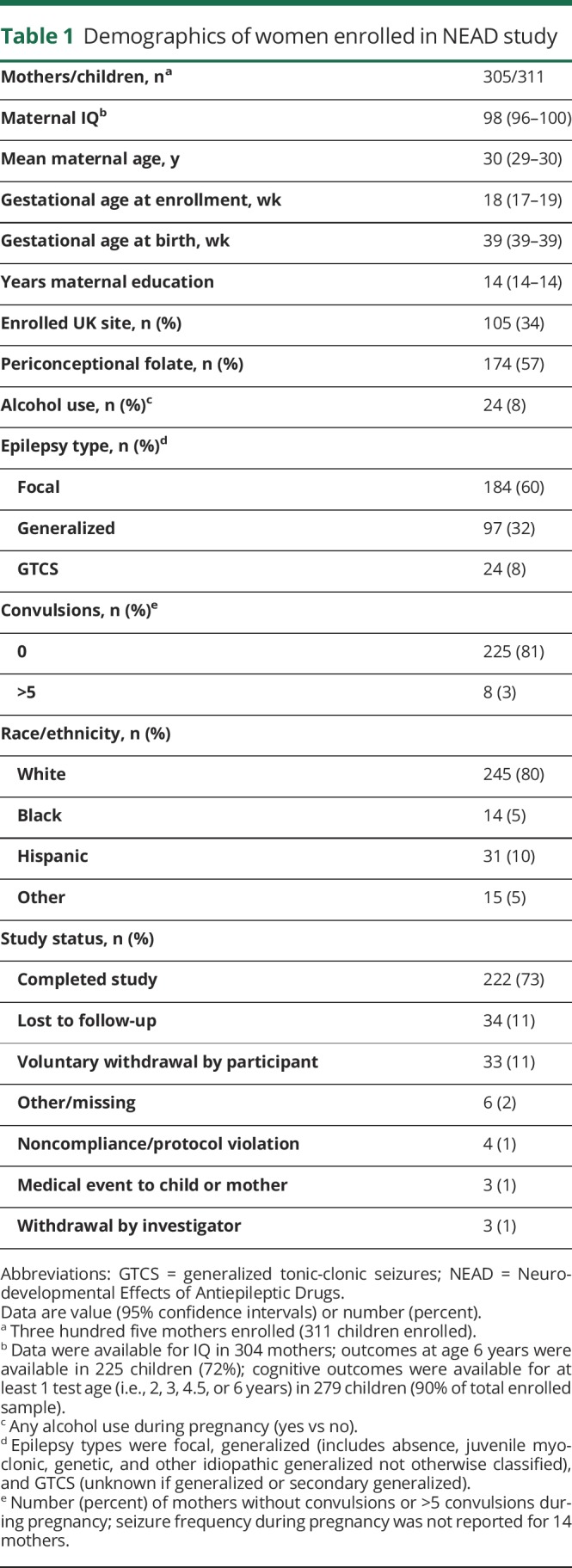

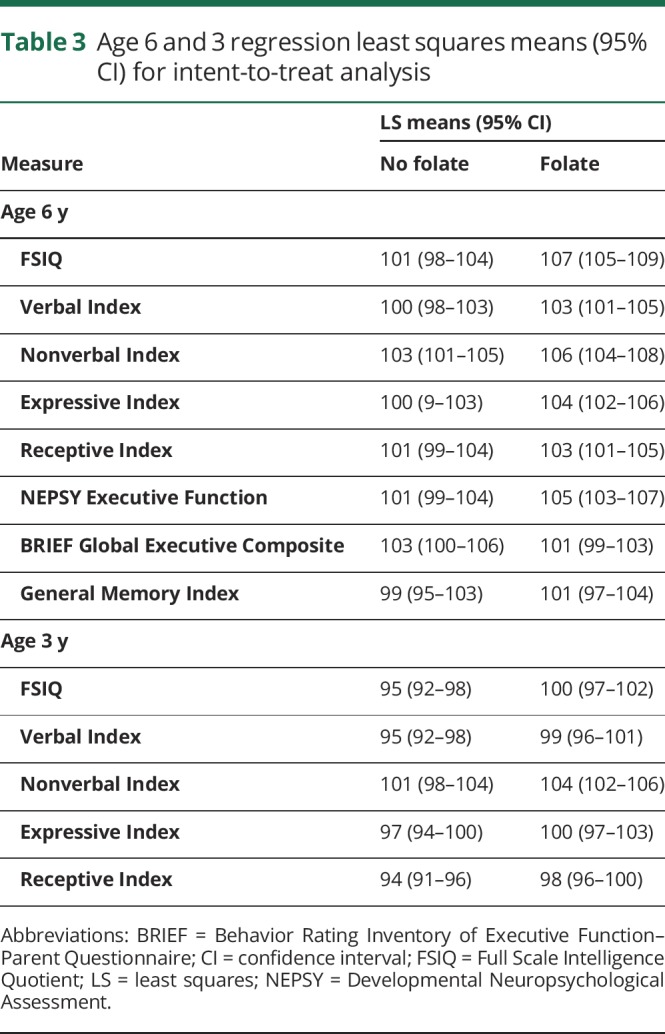

The NEAD study enrolled 305 women with epilepsy who had 311 live births. Demographics are depicted in table 1. Results of the ITT analyses at 6 years of age are the primary analyses and are depicted in table 2. As previously reported,19 FSIQ at 6 years of age was significantly related to ASM group, periconceptional folate use, maternal IQ, standardized dose, and gestational age. Periconceptional folate effects were also seen for Nonverbal Index, Expressive Language, and NEPSY Executive Function but not for Verbal Index, Receptive Index, BRIEF Executive Composite, and General Memory Index. Means (95% CIs) for individual cognitive measures as a function of folate vs no folate exposure at 6 years of age are presented in table 3. Means (95% CIs) for Verbal Index and Nonverbal Index for each ASM by folate exposure are depicted in figures 1 and 2. These differences for FSIQ was depicted in a prior publication.19

Table 1.

Demographics of women enrolled in NEAD study

Table 2.

Model summary for age 6 outcomes: intent-to-treat analysis

Table 3.

Age 6 and 3 regression least squares means (95% CI) for intent-to-treat analysis

Figure 1. Means and 95% confidence intervals for age 6 Verbal Index by antiseizure medication.

Folate (solid lines) and no folate (dashed lines).

Figure 2. Means and 95% confidence intervals for age 6 Nonverbal Index by antiseizure medication.

Folate (solid lines) and no folate (dashed lines).

Similar to 6 years of age, FSIQ at 3 years of age was significantly related to ASM group, periconceptional folate use, maternal IQ, standardized dose, and gestational age but also to maternal age (table 4). Periconceptional folate effects were also seen for Verbal Index and Receptive Index but not for Nonverbal Index and Expressive Language. Means (95% CIs) for individual cognitive measures as a function of folate vs no folate exposure at 3 years of age are presented in table 3.

Table 4.

Model summary for age 3 outcomes: Intent-to-treat analysis

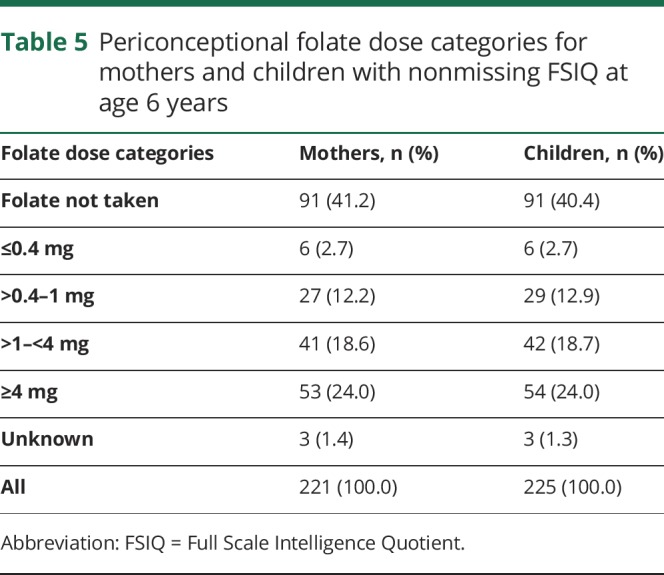

None of the ASM group by periconceptional folate interactions were significant, suggesting that the folate effects were similar across ASMs. Furthermore, similar effects were seen when children exposed to valproate were excluded (tables 2 and 4), but not as many factors were significant with the smaller sample sizes despite the fact the folate/nonfolate differences appeared less for valproate than other ASMs (figures 1 and 2). The numbers (percent) of mothers and children with nonmissing FSIQ at age 6 years exposed to different levels of folate are given in table 5. As previously published,19 an effect for periconceptional folate was seen for FSIQ at age 6 (F = 2.5, p = 0.045) with doses >0.04 mg/d showing significantly higher IQ than the no folate group.

Table 5.

Periconceptional folate dose categories for mothers and children with nonmissing FSIQ at age 6 years

Discussion

The NEAD study found positive associations of periconceptional folate exposure to better neurodevelopmental scores across a variety of cognitive variables in children of women with epilepsy taking ASMs. At 6 years of age, periconceptional folate was associated with higher FSIQ, Nonverbal Index, Expressive Language Index, and NEPSY Executive Function. However, significant effects were absent at 6 years of age for Verbal Index, Receptive Index, BRIEF Executive Function, and General Memory Index. Although the overall pattern at 3 years of age was similar, differences existed. At 3 years of age, positive associations were present for FSIQ, Verbal Index, Receptive Language Index, but nonsignificant effects were present for Nonverbal Index and Expressive Index. The pattern of findings was similar across all ASMs (see figures 1 and 2 for Verbal and Nonverbal indexes and a prior publication19 for FSIQ).

The findings from our analyses of the objective measures from the detailed neuropsychological battery of the NEAD study are consistent with the findings from the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort study in regard to the association of periconceptional folate with improved neurodevelopmental outcomes in children of women with epilepsy taking ASMs. In addition, the NEAD findings suggest that periconceptional folate effects involve multiple areas of neuropsychological function, including global, language, nonverbal, and executive functions, extending into the school-aged years, which are more predictive of adult cognitive abilities. Furthermore, the findings likely have implications beyond women with epilepsy because ASMs are among the most common teratogenic drugs prescribed to women of childbearing age, and fewer than half of ASM prescriptions are for epilepsy, the remainder being prescribed for pain and psychiatric disorders.32

Strengths of this study are our prospective design, use of assessor-blind objective cognitive assessment battery with standardized measures, and detailed monitoring of multiple potential confounding factors. Limitations are its relatively small non–population-based sample, loss to follow-up, nonrandomization, no pharmacokinetic measures, and no unexposed controls. We did not directly assess diagnoses of autism spectrum disorder. Periconceptional folate was assessed retrospectively at the time of enrollment (mean 18 weeks), and no folate levels were obtained early in pregnancy. Thus, we cannot confirm adherence to folate dosing, which is similar to the large majority of the literature on periconceptional folate.33 However, any misclassification due to errors in recollection about folate use would not be expected to be associated with the outcome measures because the information on folate collection was completed before the children were born. Ideally, a prospective study assessing folate intake and levels for folate or homocysteine before and during early pregnancy is needed to determine the effects on ultimate cognitive outcomes. In the absence of such data, we have to depend on observational studies with retrospective assessment of periconceptional folate intake. Randomized pregnancy trials of antiepileptic drugs are not possible, and observational studies might be confounded by differences in baseline characteristics (e.g., maternal IQ, ASM dose). Our analyses controlled for baseline group differences, but some residual confounding effects are possible. In addition, the present study extends assessment of periconceptional effects to several additional objective cognitive domains. Note that 7 of the 13 comparisons across 3 and 6 years of age were significant, with 1 additional measure exhibiting a statistical trend. We consider these clinically significant given that the effect of folate is seen across multiple domains.

The present study further highlights the importance of periconceptional folate to optimize outcomes in offspring from pregnancies of women taking ASMs. Note that these other studies were conducted in different cohorts and had their own strengths and limitations. The presence of a positive signal across different studies adds to the confidence in that signal.

Periconceptional folate is known to reduce the risk of spina bifida34 and may improve cognitive and behavioral neurodevelopment2–9 in pregnancies of the general population. The results of the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort study and the NEAD study suggest that periconceptional folate may be even more important for the children of women taking ASMs. Fewer than half of the pregnancies in the general population are planned, and the situation may be worse for women with epilepsy.35 About 25% of women in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort study and ≈43% in the NEAD study were not taking periconceptional folate.13,19 These issues emphasize the importance of informing women of childbearing age and encouraging folate supplementation, especially if they are taking ASMs.

The most appropriate dose of periconceptual folate is not clear. In the NEAD study, all dose groups >0.4 mg/d differed from the no folate group.19 The low-dose group (>0–0.4 mg/d) had an intermediate IQ between those of the no folate group and >0.4 mg/d groups, but it did not differ statistically from other groups. However, only 6 children were in the low-dose group (>0–0.4 mg), which limited exploring dose-dependent effects. Furthermore, the sample sizes in the higher-dose groups, although larger, are still rather small. Low folate levels as reflected by elevated maternal homocysteine at preconception are inversely associated with cognitive performance in children at 6 years after birth.36 However, concerns have been raised that higher doses of folate supplementation might be injurious and increase the risk of autism.37 Because some ASMs interfere with folate levels or mechanisms (e.g., enzyme-inducing ASMs and lamotrigine), the dose for women taking ASMs might differ from that for the general population. Higher doses could be considered for women taking ASMs that interfere with folate or women with personal or family history of neural tube defects in pregnancies, but the safety of doses >4 to 5 mg/d has been questioned.37 In addition, folic acid does not have the same metabolic pathway as folate. Folic acid requires hepatic conversion via methyl tetrahydrofolate dihydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) to be utilized, and the activity of hepatic dihydrofolate reductase varies greatly among individuals. Our study did not measure genetic variability such as the MTHFR gene. Clearly, additional studies are required to determine both the most effective and safe dose of folic acid and the timing of folate in both healthy women and women taking ASMs to achieve optimal neurodevelopment in humans. In the absence of definitive data, we recommend that folate supplementation in women of childbearing potential should be at least 0.4 to 1.0 mg/d.

The results of the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort study suggest that the critical period for folate exposure occurs in first trimester on the basis of time of supplementation; furthermore, plasma folate levels later in the pregnancy were not associated with cognitive outcomes, although they were inversely associated with autistic traits.13,14 In contrast, although the risk for congenital malformations occurs in the first trimester, the main adverse effects of ASMs on neuropsychological function might be due primarily to third trimester exposure.38,39 Fetal alcohol syndrome appears to be primarily from alcohol exposure of the immature brain in the third trimester, resulting in neuronal apoptosis and altered synaptogenesis.40 Similarly, some ASMs produce the same effect on the immature brain.38,39

The underlying mechanisms of both folate and ASMs on the immature brain and their potential interaction are poorly understood, and the precise clinical neuropsychological risks to children for most fetal ASMs exposures, including their combinations, remain unknown.41 A combination of basic and clinical research is critical to fully delineate the effects of folate and ASMs on the developing fetus to maximize the care of pregnant women who require ASMs.

Study funding

This work was supported by the NIH (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development) (NS038455 to K.J.M.), the United Kingdom Epilepsy Research Foundation (RB219738 to G.A.B.), and NIH National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke 2U01-NS038455 (K.J.M. R.M., P.B.P.).

Disclosure

K. Meador receives research support from the NIH National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, and Medtronic Navigation Inc; serves on the editorial boards of Neurology, Epilepsy & Behavior, Epilepsy & Behavior Case Reports, and Genes & Diseases; and has consulted for the Epilepsy Study Consortium, which receives money from multiple pharmaceutical companies (in relation to his work for Eisai, GW Pharmaceuticals, NeuroPace, Novartis, Supernus, Upsher Smith Laboratories, and UCB Pharma); the funds for consulting for the Epilepsy Study Consortium were paid to his university. P. Pennell has received research support from the NIH and the Epilepsy Foundation, as well as honoraria and travel support from the American Epilepsy Society, Epilepsy Foundation, NIH, and academic institutions for CME lectures. R. May and C. Brown report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. G. Baker received an educational support grant from Epilepsy Research UK and educational grants from Sanofi Aventis and UCB Pharma. Dr Baker has been an independent expert for litigation involving the administration of antiepileptic drugs in utero. R. Bromley receives research support from National Institute for Health Research and Epilepsy Research UK and has received industry consultation fees on a matter unrelated to pregnancy in epilepsy. D. Loring has received support from the NIH (2U01-NS038455) and compensation for consulting services for NeuroPace and Supernus and is an associate editor for Epilepsia, Critically Appraised Topics editor for The Clinical Neuropsychologist, and editor-in-chief for Neuropsychology Review. M. Cohen receives royalties from The Psychological Corporation, Pearson as author of the Children's Memory Scale. Go to https://n.neurology.org/lookup/doi/10.1212/WNL.0000000000008757 for full disclosures.

Glossary

- ASM

antiseizure medication

- CI

confidence interval

- DAS

Differential Ability Scales

- DTVMI-5

Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration–5th Edition

- FSIQ

Full Scale Intelligence Quotient

- ITT

intent-to-treat

- MTHFR

methyl tetrahydrofolate dihydrofolate reductase

- NEAD

Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs

- NEPSY

Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment

- PLS-4

Preschool Language Scale–4th Edition

- PPVT-4

Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test–4th Edition

Appendix 1. Author

Appendix 2. NEAD Sites and Study Group

Footnotes

CME Course: NPub.org/cmelist

References

- 1.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Folic Acid: Recommendations. Available at: cdc.gov/ncbddd/folicacid/recommendations.html. Accessed December 27, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roth C, Magnus P, Schjølberg S, et al. Folic acid supplements in pregnancy and severe language delay in children. JAMA 2011;306:1566–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatzi L, Papadopoulou E, Koutra K, et al. Effect of high doses of folic acid supplementation in early pregnancy on child neurodevelopment at 18 months of age: the mother-child cohort “Rhea” study in Crete, Greece. Public Health Nutr 2012;15:1728–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Julvez J, Fortuny J, Mendez M, et al. Maternal use of folic acid supplements during pregnancy and four-year-old neurodevelopment in a population-based birth cohort. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2009;23:199–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villamor E, Rifas-Shiman SL, Gillman MW, Oken E. Maternal intake of methyl-donor nutrients and child cognition at 3 years of age. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2012;26:328–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roza SJ, van Batenburg-Eddes T, Steegers EAP, et al. Maternal folic acid supplement use in early pregnancy and child behavioural problems: the Generation R Study. Br J Nutr 2010;103:445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schlotz W, Jones A, Phillips DIW, et al. Lower maternal folate status in early pregnancy is associated with childhood hyperactivity and peer problems in offspring. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2010;51:594–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wehby GL, Murray JC. The effects of prenatal use of folic acid and other dietary supplements on early child development. Matern Child Health J 2008;12:180–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao Y, Sheng C, Xie RH, et al. New perspective on impact of folic acid supplementation during pregnancy on neurodevelopment/autism in the offspring children: a systematic review. PLoS One 2016;11:e0165626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harden CL, Meador KJ, Pennell PB, et al. Practice parameter update: management issues for women with epilepsy-focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): teratogenesis and perinatal outcomes: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee and Therapeutics and Technology Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Neurology 2009;73:133–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ban L, Fleming KM, Doyle P, et al. Congenital anomalies in children of mothers taking antiepileptic drugs with and without periconceptional high dose folic acid use: a population-based cohort study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0131130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al. Comparative risk of major congenital malformations with eight different antiepileptic drugs: a prospective cohort study of the EURAP registry. Lancet Neurol 2018;17:530–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Husebye ESN, Gilhus NE, Riedel B, Spigset O, Daltveit AK, Bjørk MH. Verbal abilities in children of mothers with epilepsy: association to maternal folate status. Neurology 2018;91:e811–e821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bjørk M, Riedel B, Spigset O, et al. Association of folic acid supplementation during pregnancy with the risk of autistic traits in children exposed to antiepileptic drugs in utero. JAMA Neurol 2018;75:160–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasradze S, Gogatishvili N, Lomidze G, et al. Cognitive functions in children exposed to antiepileptic drugs in utero: study in Georgia. Epilepsy Behav 2017;66:105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker GA, Bromley RL, Briggs M, et al. IQ at 6 years after in utero exposure to antiepileptic drugs: a controlled cohort study. Neurology 2015;84:382–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, et al. Cognitive function at 3 years of age after fetal exposure to antiepileptic drugs. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1597–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, et al. Foetal antiepileptic drug exposure and verbal versus non-verbal abilities at three years of age. Brain 2011;134:396–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, et al. Fetal antiepileptic drug exposure and cognitive outcomes at age 6 years (NEAD study): a prospective observational study. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:244–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen MJ, Meador KJ, Browning N, et al. Fetal antiepileptic drug exposure: adaptive and emotional/behavioral functioning at age 6 years. Epilepsy Behav 2013;29:308–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sattler JM. Assessment of Children: Cognitive Foundations, 5th ed. San Diego: Jerome M. Sattler Publisher, Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elliott CD. Differential Abilities Scales. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zimmerman IL, Steiner VG, Pond RE. Preschool Language Scale, 4th ed. San Antonio: Pearson Education, Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunn L, Dunn D. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, 4th ed. Minneapolis: Pearson Assessments; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beery KE. Developmental Test of Visual Motor Integration. Cleveland: Modern Curriculum; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen MJ. The Children's Memory Scale. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gioa GA, Isquith PK, Guy SC, Kenworthy L. Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Korkman M, Kirk U, Kemp S. NEPSY: A Developmental Neuropsychological Assessment. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brownell R. Expressive One-word Picture Vocabulary Test. Novato: Academic Therapy Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li KH. Imputation using Markov chains. J Stat Comput Simul 1988;30:57–79. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical Analysis With Missing Data, 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bobo WV, Davis RL, Toh S, et al. Trends in the use of antiepileptic drugs among pregnant women in the US, 2001-2007: a medication exposure in pregnancy risk evaluation program study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2012;26:578–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tamura T, Goldenberg RL, Chapman VR, Johnston KE, Ramey SL, Nelson KG. Folate status of mothers during pregnancy and mental and psychomotor development of their children at five years of age. Pediatrics 2005;116:703–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De-Regil LM, Peña-Rosas JP, Fernández-Gaxiola AC, Rayco-Solon P. Effects and safety of periconceptional oral folate supplementation for preventing birth defects. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015. Dec 14;(12):CD007950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herzog AG, Mandle HB, MacEachern DB. Association of unintended pregnancy with spontaneous fetal loss in women with epilepsy: findings of the Epilepsy Birth Control Registry. JAMA Neurol 2019;76:50–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy MM, Fernandez-Ballart JD, Molloy AM, Canals J. Moderately elevated maternal homocysteine at preconception is inversely associated with cognitive performance in children 4 months and 6 years after birth. Matern Child Nutr 2017;13:e12289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murray LK, Smith MJ, Jadavji NM. Maternal oversupplementation with folic acid and its impact on neurodevelopment of offspring. Nutr Rev 2018;76:708–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forcelli PA, Kozlowski R, Snyder C, Kondratyev A, Gale K. Effects of neonatal antiepileptic drug exposure on cognitive, emotional, and motor function in adult rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2012;340:558–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ikonomidou C, Turski L. Antiepileptic drugs and brain development. Epilepsy Res 2010;88:11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ikonomidou C, Bittigau P, Ishimaru MJ, et al. Ethanol-induced apoptotic neurodegeneration and fetal alcohol syndrome. Science 2000;287:1056–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meador KJ, Loring DW. Developmental effects of antiepileptic drugs and the need for improved regulations. Neurology 2016;86:297–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data included in these analyses will be shared as anonymized data via request from any qualified investigator.