Abstract

Insect symbionts are major manipulators of host’s behavior. Their effect on parameters such as fecundity, male mating competitiveness, and biological quality in general, can have a major influence on the effectiveness of the sterile insect technique (SIT). SIT is currently being developed and applied against human disease vectors, including Ae. albopictus, as an environment-friendly method of population suppression, therefore there is a renewed interest on both the characterization of gut microbiota and their exploitation in artificial rearing. In the present study, bacterial communities of eggs, larvae, and adults (both males and females) of artificially reared Ae. albopictus, were characterized using both culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches. Mosquito-associated bacteria corresponding to thirteen and five bacteria genera were isolated from the larval food and the sugar solution (adult food), respectively. The symbiont community of the females was affected by the provision of a blood meal. Pseudomonas and Enterobacter were either introduced or enhanced with the blood meal, whereas Serratia were relatively stable during the adult stage of females. Maintenance of these taxa in female guts is probably related with blood digestion. Gut-associated microbiota of males and females were different, starting early after emergence and continuing in older stages. Our results indicate that eggs contained bacteria from more than fifteen genera including Bacillus, Chryseobacterium, and Escherichia–Shigella, which were also main components of gut microbiota of female adults before and after blood feeding, indicating potential transmission among generations. Our results provided a thorough study of the egg- and gut-associated bacteria of artificially reared Ae. albopictus, which can be important for further studies using probiotic bacteria to improve the effectiveness of mosquito artificial rearing and SIT applications.

Keywords: Aedes albopictus, gut, microbiota, artificial rearing, SIT, culture-dependent, culture-independent

Introduction

The tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, is known to carry dengue, chikungunya, and Zika viruses. Together with its closely related species Aedes aegypti they represent, in addition to significant biting nuisance, a serious health threat to more than three billion people in over 120 countries (Brady et al., 2012; WHO, 2017). The population control of these mosquito species is challenging due to the inefficiency of current conventional control methods, which are largely based on the removal of breeding sites and use of insecticides (Bourtzis et al., 2016; Pang et al., 2017; Flores and O’Neill, 2018). Several novel population suppression methods have been developed against Aedes species and some of them, including the sterile insect technique (SIT), the incompatible insect technique (IIT), the combined SIT/IIT and the Release of Insects carrying Dominant Lethals (RIDL), are currently being tested in small scale pilot trials (Bourtzis et al., 2016; Flores and O’Neill, 2018; Zheng et al., 2019).

All these methods should ideally be used as a component in area-wide integrated pest management programs (AW-IPM) (Bourtzis et al., 2016; Bouyer and Marois, 2018). They all depend on the mass rearing, sex separation, sterilization (or lethality), handling, packing, transportation and continuous release, at overflooding ratios, of males in the field to suppress a target population (Lees et al., 2015; Bourtzis et al., 2016). So, large production of high-quality males is required since they should be released at large numbers and should also be able to compete with wild males for mating with wild females. However, the mass rearing process, handling, packing, transportation and release as well as the irradiation (SIT), the infection with a bacterial symbiont such as Wolbachia (IIT or combined SIT/IIT) or the insertion of a transgene (RIDL) may have a negative effect in the life history traits of the mass reared insect strain and the overall biological quality of the released males (Lees et al., 2015; Bourtzis et al., 2016).

Many bacterial species have established long evolutionary and intimate symbiotic associations with insects affecting many aspects of their biology, ecology and evolution including nutrition, metabolism, immune function, physiology as well as reproduction and behavior (Dillon and Dillon, 2004; Bourtzis and Miller, 2009; Zchori-Fein and Bourtzis, 2011; Engel and Moran, 2013). There have been several studies which have focused on the characterization of the bacterial communities associated with insects, their role in the host biology as well as their potential exploitation to develop and/or enhance novel strategies to control populations of pests and disease vectors including mosquitoes (Douglas, 2015; Berasategui et al., 2016; Arora and Douglas, 2017; Flores and O’Neill, 2018).

As previous studies in fruit flies have shown, the biological quality and the overall ecological fitness of the insects highly depends on their associated bacterial and other microbial partners (Shelly and McInnis, 2003; Niyazi et al., 2004; Ben-Yosef et al., 2008; Ben Ami et al., 2010; Gavriel et al., 2011; Storelli et al., 2011; Blum et al., 2013; Hamden et al., 2013; Sacchetti et al., 2014; Augustinos et al., 2015; Kyritsis et al., 2017; Cai et al., 2018; Khaeso et al., 2018; Akami et al., 2019). Therefore, insect symbiotic bacterial species can be used as probiotics to improve key parameters of population suppression strategies, including the productivity of mass reared strains as well as the mating performance and longevity of sterile males (Niyazi et al., 2004; Ben Ami et al., 2010; Gavriel et al., 2010; Yuval et al., 2013; Augustinos et al., 2015; Kyritsis et al., 2017; Cai et al., 2018).

There is an increasing interest in the structure of mosquito-associated microbiota as well as the interactions between the host and the microbes (for recent reviews see Guegan et al., 2018; Strand, 2018; Scolari et al., 2019), due to the role of the associated microbes in the biology of their hosts and the immunity and pathogen interference. The latter is critical for the development and application of novel population suppression and population modification strategies against major mosquito vector species (Flores and O’Neill, 2018; Guegan et al., 2018). Many studies have investigated the role of the environment and the breeding sites on microbial acquisition in Aedes, Anopheles, and Culex mosquitoes and have shown that there is a clear overlap of bacterial composition between mosquito species, developmental stages, and habitats (for a recent review see Guegan et al., 2018). In addition, the concept of mosquito core- and pan-microbiota has been investigated and recent data clearly indicate that environmental factors and food resources play a major role in the environmental bacterial acquisition and this may determine key biological properties of the mosquito hosts (Pastoris et al., 1989; Lindh et al., 2005; Rani et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2011, 2018; Minard et al., 2013a, b; Guegan et al., 2018). Sex, female size, and genetic diversity have been shown to affect the associated microbiota in Ae. albopictus with the overall bacterial diversity of both Ae. albopictus and Ae. koreicus being significantly lower in recently invaded regions (Minard et al., 2018; Rosso et al., 2018).

Interestingly, some bacterial species (such as Wolbachia, Asaia, and Elizabethkingia) may have interstadial transmission, for example from pupae to adults or via maternal transmission (Kittayapong et al., 2002; Favia et al., 2007; Akhouayri et al., 2013; Ngwa et al., 2013). Differences in the bacterial diversity between males and females have been partly attributed to differences in the flight dispersal and blood feeding (Foster, 1995; Demaio et al., 1996; Pumpuni et al., 1996; Zayed and Bream, 2003; Gusmao et al., 2010; Kumar et al., 2010; Benoit et al., 2011; Gaio et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011; Zouache et al., 2011). A number of studies has also shown that mosquito-associated bacterial species may affect both metabolism and life history traits including blood and sugar digestion, supply of vitamins and amino acids, body size, oviposition site choice and egg production, longevity, sex ratio, larval development as well as virus dissemination (Chouaia et al., 2012; Mitraka et al., 2013; Sharma et al., 2013; Coon et al., 2014, 2016a,b, 2017; Muturi et al., 2016; Dickson et al., 2017; Guegan et al., 2018).

The Insect Pest Control Laboratory of the Joint FAO/IAEA Division of Nuclear Applications in Food and Agriculture has been developing the SIT-based approaches for the population control of Ae. albopictus and guidelines for mass-rearing laboratory populations of insects that are targets for SIT. Given the importance of the gut-associated microbiota for the rearing process and the overall biological quality of artificially produced insects for SIT-based applications, the present study focused on the characterization of the gut-associated bacterial species of a laboratory strain of Ae. albopictus under artificial rearing conditions for potential SIT-based applications. The characterization was performed using culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches, throughout the mosquito developmental stages (egg, larva and adult), at different adult ages (both young and old males and females) and female feeding regimes (sugar or blood). The density levels of key bacterial partners were assessed, and the overall findings are discussed from an applied perspective towards the use of SIT-based approaches for the population suppression of this major mosquito vector species.

Materials and Methods

Mosquito Strains and Maintenance

The experiments were conducted at the Joint FAO/IAEA Insect Pest Control Laboratory (hereafter IPCL), Seibersdorf, Austria. Aedes albopictus wild type strain (Guangzhou, China), known as GUA strain (Zhang et al., 2015) at F13 generation, was used in these experiments. Egg hatching, larval rearing, and adult maintenance were carried out as previously reported (Zhang et al., 2015). Laboratory-reared cyclic colony was maintained under at 26 ± 1°C, 60 ± 10% RH with a photoperiod of 12: 12 h (L: D).

Sample Collection and Dissection

Blood meals were provided to the GUA females aged 7- to 9-days post emergence. Two days after the blood meal, a plastic 250-ml beaker containing 100 mL sterilized deionized water and a strip of sterilized white filter paper (white creped papers IF C140, Industrial Filtro S.r.l., Cologno Monzese, Italy) were placed in the cage (30 × 30 × 30 cm, BugDorm 1, MegaView, Taichung, Taiwan). Fresh eggs (less than 4 h) were collected and counted (approximately 100 for each replicate) as materials for bacterial culture. The rest of the eggs were maintained in the adult rearing room for 7 days for maturation and then hatched as previously described (Zhang et al., 2015). Larvae were fed on modified IAEA liquid larvae diet (Balestrino et al., 2014). The whole gut of the 3rd instar larvae (L3) was dissected and was used as source for the isolation of cultivable bacterial species. Pupae were collected and separated using an improved Fay-Morlan separator (Dame et al., 1974; Focks, 1980).

Male and female pupae were reared separately in sterilized deionized water and placed in cage for emergence. Non-fed less than 24 h old adults (both males and females) were collected and were used for the dissection of whole guts. The rest of the adults were supplied with 10% sucrose solution. Part of the females were offered with defibrinated pig blood (Rupert Seethaler, Vienna, Austria) in sausages (EDICAS, Girona, Spain) from 7th day to 9th day after emergence. Whole guts of blood-fed females were dissected at the 14th day after emergence to allow full digestion of blood. In parallel, whole guts of males and non-blood fed females were also collected. Ventral diverticulum and Malpighian tubules were removed from all gut samples.

Samples from seven groups, including eggs (EGG), dissected guts of larvae (LAR), up to 1-day old non-fed males (1DM), up to 1-day old non-fed females (1DF), 14 days old sucrose-fed males (14DM), 14 days old non-blood fed (sucrose-fed) females (NBF), and 14 days old blood-fed females (BFF) were included in both culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches. Fresh eggs were collected with sterilized dissecting needles. Alive adults which had been anesthetized at 4°C and alive larvae were surface disinfected by dipping in 70% ethanol for 1 min, placed into 1 × PBS (phosphate buffer saline) for rinsing, and then dissected in PBS under a binocular microscope with sterilized needles to get whole guts under aseptic conditions. One hundred fresh eggs or 5 whole guts were pooled to create one sample (replicate).

Culture-Dependent Approaches

For the isolation of cultivable gut bacteria, samples were collected in 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes with 200 μL sterile LB medium (Invitrogen). Samples were mechanically crushed using sterile pestles and 800 μL LB were added to make a total volume of 1,000 μL. The homogenate was serially diluted (from 100 to 10–4) and plated on three types of agar media, one non-selective (LB Agar, Life technologies) and two types of selective media, Chromocult Agar ES and XLD Agar (Merck Millipore). Three replicates with 100 μL solution were used for each medium. Plates were incubated in incubator (IPP110, Memmert, United States) at 26°C for 16 h (or until bacterial colonies were visible but incubation did not exceed 48 h). From the dilution series, those plates with 10 to 300 bacterial colonies were used and the number of colony-forming units (CFU) in the original solution was calculated.

Appropriate controls were also prepared, including (a) EGG-liquid: one hundred eggs were washed in 200 μL LB medium by vortex and gently centrifuged to get 100 μL supernatant as potential source of bacteria; (b) Larval food: this control was prepared with larvae diet (30 mL/L) which was maintained in a rearing room for 48 h and (c) Sugar solution: this was collected from both females’ and males’ cages at the 14th day post emergence.

Twenty bacterial isolates for each sample treatment and 12 for each control sample (eggs, larval food or sugar solution) were selected based on bacterial colony characteristics such as color, size, shape, opacity, margin, elevation and viscosity. Three rounds of streaking and isolation were performed on the corresponding medium to ensure that the bacterial isolates were pure cultures. Purified isolates were cultivated in LB medium at 26°C for 16–20 h, and then stored in 25% glycerol at −80°C.

Colony Characterization Using 16S rRNA Gene-Based RFLP Assay

PCR was performed on 1 μL fresh culture liquid using 2 × Taq mix (Qiagen) and the universal 16S rRNA gene primers 27F/1492R (Edwards et al., 1989; Weisburg et al., 1991) with MJ Research Tetrad PTC-225 Thermal Cycler (GMI, United States). The PCR cycling conditions were template denaturation at 95°C for 10 min followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 45 s, primer annealing at 55°C for 1 min, and primer extension at 72°C for 2 min; a final extension step of 10 min at 72°C was also included. In case that amplification failed, PCR was carried out again with DNA extracted using Dneasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen) after lysozyme (SIGMA) digestion (resuspended in the lysis buffer with 10 mg/mL lysozyme and digested at 37°C for 2 h). Part of each PCR reaction (5/50 μL) was electrophoresed on 1.5% agarose gels, and all amplicons of the expected size were individually digested with restriction endonucleases TaqI, EcoRI, HaeIII and RsaI (Thermo) according to manufacturer’s suggestions. Specifically, 5–15 μL per amplicon were digested, using 2 μL 10 × buffer and 3–5 μL enzyme, in a final volume of 20 μL. Reactions were kept for 3–4 h at 37°C, then inactivated at 80°C and electrophoresed on 2% agarose gels. In case the selected bacterial isolates with different colony morphology characteristics were found to present quite similar RFLP patterns for all 4 enzymes, digestion with an additional restriction enzyme (AsuII, MfeI or HgaI, Thermo) was included for its genotyping or their 16S rRNA gene was sequenced double stranded (see below).

16S rRNA Gene Sequencing and Data Analyzing

From each bacterial group and taking into consideration the RFLP pattern and colony morphology, 2–7 bacterial isolates were selected for sequencing of almost the entire 16S rRNA gene. PCR products were purified using the High Pure PCR product purification kit (Roche, Germany) and sequenced double stranded (VBC, Austria by using the 27F-1492R initial primer set and 4 internal primers: 519R, 596F, 960R and 1114F (Reed et al., 2002).

All 16S rRNA gene sequences were assembled in Sequencher 4.14, aligned with Clustal X 1.83 and BioEdit 7.01. Isolates with identical sequences were recognized with a different number. Sequences were examined for chimeras using the DECIPHER’s web tool1 and USEARCH 6.02. Taxonomy assignment was performed using BLASTN3 and the closest relative was assigned using RDP classifier4. Alignment of sequences was carried out using MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004). A phylogenetic tree, based on the distance matrix method, was constructed using the software package Geneious 8. Evolutionary distances were calculated using the Jukes-Cantor model, and topology was inferred using the “neighbor-joining” method. A phylogenetic tree calculated by maximum parsimony, using the PAUP phylogenetic package, was also generated. Sequences with 1180 bp length were used for tree constructions.

Culture-Independent Approaches-Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) and Statistical Analysis

Eggs and guts were mechanically crushed using sterile pestles in liquid nitrogen. DNA was extracted following the protocol of Dneasy Blood and Tissue Kit. If required, DNA was concentrated into >15 ng/μL, and three replicates per sample were prepared and sent for 16S rRNA gene sequencing using the MiSeq Illumina platform to the IMGM Laboratories GmbH (Martinsried, Germany) targeting two different regions with primers U341F (5′-CCTACGGGRSGCAGCAG-3′) and 805R (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′) and 909F (5′-ACTCAAAKGAATWGACGG-3′) and 1391R (5′-GACGGGCGGTGWGTRCA-3′). The 16S rRNA gene sequences reported in this study have been deposited in NCBI under Bioproject number PRJNA575054, while the Sanger generated sequences have been deposited under accession numbers MN540103 to MN540125.

De-multiplexing and conversion to FASTQ format was performed using Qiime 1.9.1 (Caporaso et al., 2010b). Pair-end reads were assembled, trimmed and corrected for error using PandaSeq (Masella et al., 2012). Unassembled reads and reads outside the range of 440 to 450 bp once assembled were discarded. All subsequent analyses were conducted in QIIME version 1.9.1 (Caporaso et al., 2010b). Sequences were clustered into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) using USEARCH (Edgar, 2010) by open-reference OTU picking. Chimeras were detected and omitted using the program UCHIME (Edgar et al., 2011) with the QIIME-compatible version of the SILVA 111 release database (Quast et al., 2013). The most abundant sequence was chosen as the representative for each OTU. Taxonomy was assigned to representative sequences by BLAST (Altschul et al., 1990) against the SILVA 111 release database (Quast et al., 2013). Representative sequences were aligned against the SILVA core reference alignment using PyNAST (Caporaso et al., 2010a). Alpha-diversity indices, as well as indices depicting the population structure, were calculated with the QIIME pipeline (Caporaso et al., 2010b) based on the rarefied OTU table at a depth of 15,000 sequences/sample (observed species, PD whole tree, chao1 and simpson reciprocal). Inter-sample diversity was calculated using Bray-Curtis distances while Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) and multidimensional scaling (MDS) plot (Anderson, 2001) was performed on the resulting distance matrix. These calculations and those for alpha diversity were performed in QIIME version 1.9.1. ANOVA and Tukey–Kramer post hoc tests were employed to detect statistical differences (Edgar, 2010). Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA) analyses were applied to Bray–Curtis similarity matrices to compute similarities between groups (Anderson, 2001). Community structure differences were viewed using the constrained ordination technique CAP (Canonical Analysis of Principal Coordinates), using the CAP classification success rate and CAP traceQ_m’HQ_m statistics, and were performed with 9999 permutations within PRIMER version 6+ (Anderson and Willis, 2003).

Semi-Quantitative Analysis of Main Gut Bacteria Groups

qPCR-based semi-quantitative analysis was performed for some of the most relatively abundant genera (Aeromonas, Asaia, Elizabethkingia and Chryseobacterium, Enterococcus, and Wolbachia) detected by the 16S rRNA gene next generation sequencing (NGS). The qPCR analysis was carried out in three replicates on the same samples used for the NGS. It was difficult to design genus specific primers for Elizabethkingia, so this genus was studied as a group together with Chryseobacterium. The sequence of the primers and other relevant information for the qPCRs are presented in Supplementary Table 1. The Ae. albopictus ribosomal protein S6 (rps6) gene was used as control (for calibration).

A gradient PCR was initially performed to standardize the PCR conditions. PCR amplification was performed with an initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 57–64°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 45 s, and kept under 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were analyzed on agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm the presence of the specific amplicon. These conditions were then used to perform qPCR analysis (Supplementary Table 1). The amplification was performed using iQTM SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, United States). The reaction mixture (15 μL) consisted of 5 ng DNA template, 2–5 pmol of each primer and 7.5 μL of 2 × Supermix. qPCR was performed with a CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, United States). Due to the different annealing temperatures (Supplementary Table 1), the reactions for the target genes and the housekeeping gene were put on different plates. An initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 min was followed by 40 cycles consisting of denaturation at 95°C for 10 s, at annealing temperature for 60 s. To check and confirm the quality of amplification, a melting profile was generated for the amplicon over a temperature range of 65°C to 95°C. Melting curves for each sample were analyzed after each run to check the specificity of amplification. Cq of products was calculated using CFX ManagerTM Software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Relative density of selected bacterial taxa was determined by using the 2–ΔΔCT calculation method. Three biological replicates were employed for each sample (with the exception of 14DM for which only 2 replicates were used for the Asaia and Chryseobacterium-Elizabethkingia group reactions), and 2 technical replicates of qPCR were carried out for each reaction.

Statistical Analysis of Data

Statistical analysis were carried out with JMP 14.3.0 (2018, SAS, Cary, NC, United States). The average of relative density of 2 technical replicates was used for each biological replicate. The mean and standard error (SE) of relative density was calculated, and comparisons of relative density of selected bacterial taxa between sample groups were assessed using ANOVA followed by Tukey–Kramer HSD.

Results

Isolation and Characterization of Cultivable Bacterial Species During the Development of Aedes albopictus

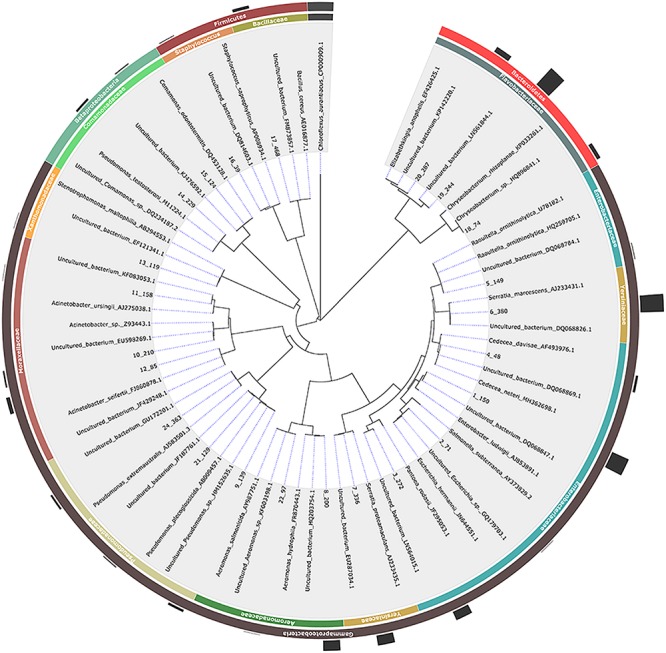

Using three different microbiological media (LB Agar, Chromocult Agar ES and XLD Agar), 462 bacterial isolates were isolated in total including 73 isolates from the three control samples. The selection of the colonies was mainly based on colony morphology since our goal was to isolate as many different bacterial species as possible for further investigation. A 16S rRNA gene-based PCR-RFLP assay was employed for the initial characterization and grouping of the bacterial isolates. Restriction endonucleases EcoRI, AsuII, MfeI and HgaI exhibited up to maximum one recognition site, whereas TaqI, HaeIII and RsaI displayed multiple ones (Supplementary Table 2). According to the PCR-RFLP data, the bacterial isolates were placed in 27 groups. Up to two representatives from each group were selected for 16S rRNA gene sequencing and the sequencing data revealed the presence of 23 unique bacterial isolates, belonging to Proteobacteria (mainly members of Gammaproteobacteria), Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes (mainly members of Flavobacteriaceae) (Table 1 and Figure 1). Members of the Acinetobacter, Bacillus, Cedecea, Chryseobacterium, Comamonas, Elizabethkingia, Enterobacter, Escherichia, Pseudomonas, Serratia, Staphylococcus, and Stenotrophomonas genera, were retrieved from eggs and the digestive track of adult mosquitoes. Members of the Raoultella genus, as well as members of the Acinetobacter and Pseudomonas (but different from the ones detected in the eggs and the digestive track of adult mosquitoes), were isolated only in larval food, but not in adult mosquitoes (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial isolates obtained from Ae. albopictus; and cultivable close phylogenetic relatives (identity > 97%) from Aedes, other mosquito or other insects.

| Sample code | Accession Number | Stage/Medium (Times isolated) | Phylogenetic linkage | Phylogenetic relative and Isolation source | References | Accession No. | Identity(%) |

| 1_150 | MN540103 | Sugar solution from females’ cage-CC, LB, XLD (24) | Enterobacter sp. | Enterobacter sp., Ae. albopictus male adult, wild-caught | Zouache et al., 2011 | GU726184.1 | 98.84 |

| BFF-CC (1) | |||||||

| LAR-CC, LB, XLD (24) | |||||||

| Larval food-CC, LB, XLD (19) | |||||||

| 2_71 | MN540104 | LAR-LB (1) | Escherichia sp. | Klebsiella pneumoniae, Ae. aegypti (Rockefeller) female adult, lab-rearing | Terenius et al., 2012 | JN201948.1 | 97.54 |

| Escherichia hermannii (non-mosquito source) | JN644551.1 | 100 | |||||

| 3_272 | MN540105 | BBF-CC, XLD (3) | Enterobacter sp. | Enterobacter sp., Ae. albopictus male adult, wild-caught | Zouache et al., 2011 | GU726182.1 | 97.54 |

| 1DF-CC, LB (26) | |||||||

| 1DM-CC, LB (5) | |||||||

| 4_48 | MN540106 | EGG-CC (5) | Cedecea sp. | Enterobacter sp., Ae. albopictus male adult, wild-caught | Zouache et al., 2011 | GU726183.1 | 97.75 |

| Cedecea neteri (non-mosquito source) | MH362698.1 | 100 | |||||

| EGG-liquid-CC (3) | |||||||

| LAR-LB (1) | |||||||

| 5_149 | MN540107 | Larval food-XLD (2) | Raoultella sp. | Serratia marcescens, Ae. aegypti (Rockefeller) female adult, lab-rearing | Terenius et al., 2012 | JN201947.1 | 97.75 |

| Raoultella ornithinolytica_ | HQ259705.1 | 100 | |||||

| 6_380 | MN540108 | NBF-CC, LB, XLD (47) | Serratia sp. | Serratia marcescens, Ae. aegypti (Rockefeller) female adult, lab-rearing | Terenius et al., 2012 | JN201947.1 | 99.52 |

| EGG-CC, LB, XLD (41) | |||||||

| 7_336 | MN540109 | BFF-CC, LB, XLD (35) | Serratia sp. | Serratia sp., Delia radicum larvae, lab-rearing | Welte et al., 2016 | KP836246.1 | 97.95 |

| NBF-CC (1) | |||||||

| 1DF-CC (2) | |||||||

| 8_200 | MN540110 | 1DF-CC, LB, XLD (5) | Aeromonas sp. | Aeromonas hydrophila, An. maculipennis, stage unknown, wild-caught | GU204971.1 | 98.64 | |

| 1DM-LB, XLD (32) | |||||||

| LAR-XLD (2) | |||||||

| 9_139 | MN540111 | Larval food-CC, LB (9) | Pseudomonas sp. | Pseudomonas sp., Ae. albopictus, female adult, lab-rearing | Zouache et al., 2009 | FJ688378.1 | 97.40 |

| 10_230 | MN540112 | 1DM-CC (6) | Acinetobacter sp. | Acinetobacter beijerinckii, Cx. Quinquefasciatus, female adult, wild-caught | Chandel et al., 2013 | JN644620.1 | 97.34 |

| 11_158 | MN540113 | Larval food-CC (1) | Acinetobacter sp. | Acinetobacter sp., Glossina pallidipes, stage unknown, wild-caught | MG162615.1 | 98.15 | |

| 12_85 | MN540114 | 1DM-CC (3) | Acinetobacter sp. | Acinetobacter sp. Ae. albopictus, female adult, lab-rearing | Zouache et al., 2009 | FJ688379.1 | 99.25 |

| LAR-CC, LB (11) | |||||||

| 13_119 | MN540115 | LAR-CC (1) | Stenotrophomonas sp. | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, An. gambiae, female adult, lab-rearing | Lindh et al., 2008 | EF426435.1 | 99.45 |

| 14_229 | MN540116 | 1DF-LB (1) | Comamonas sp. | Comamonas sp., Ae. albopictus, female adult, lab-rearing | Zouache et al., 2009 | FJ688377.1 | 100 |

| 1DM-CC, LB (7) | |||||||

| 15_124 | MN540117 | LAR-CC, LB (4) | Comamonas sp. | Comamonas odontotermitis, Odontotermes formosanus, wild-caught | Chou et al., 2007 | NR_043859.1 | 99.93 |

| 16_39 | MN540118 | EGG-LB (2) | Staphylococcus sp. | Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Cx. Quinquefasciatus, female adult, wild-caught | Chandel et al., 2013 | JN644617.1 | 99.46 |

| 17_468 | MN540119 | Sugar solution from females’ cage-LB (6) | Bacillus sp. | Bacillus cereus, Ae. albopictus female adult, wild-caught | Zouache et al., 2011 | GU726173.1 | 99.66 |

| Sugar solution from females’ cage-LB (2) | |||||||

| LAR-LB (1) | |||||||

| Larval food-LB (2) | |||||||

| 18_74 | MN540120 | LAR-CC, LB (14) | Chryseobacterium sp. | Chryseobacterium sp., Cx. Quinquefasciatus, female adult, wild-caught | Chandel et al., 2013 | HQ154575.1 | 97.98 |

| 19_244 | MN540121 | BFF-LB (14) | Elizabethkingia sp. | Elizabethkingia meningoseptica, Ae. aegypti (Rockefeller) female adult, lab-rearing | Terenius et al., 2012 | JN201943.1 | 97.92 |

| NBF-LB (12) | |||||||

| 14DM-CC, LB (40) | |||||||

| EGG-CC, LB (12) | |||||||

| EGG-liquid-CC (4) | |||||||

| 20_287 | MN540122 | 1DF-CC, LB (21) | Elizabethkingia sp. | Elizabethkingia meningoseptica, Ae. aegypti (Rockefeller) female adult, lab-rearing | Terenius et al., 2012 | JN201943.1 | 98.34% |

| 21_129 | MN540123 | Larval food-LB (3) | Pseudomonas sp. | Pseudomonas sp., Ae. albopictus, female adult, lab-rearing | Zouache et al., 2009 | FJ688378.1 | 97.26 |

| 22_97 | MN540124 | Larval food-XLD (1) | Aeromonas sp. | Aeromonas hydrophila, An. maculipennis, stage unknown, wild-caught | GU204971.1 | 98.57 | |

| 24_363 | MN540125 | BFF-CC, LB (7) | Pseudomonas sp. | Pseudomonas ficuserectae, Cx. Quinquefasciatus, female adult, wild-caught | Chandel et al., 2013 | JN644593.1 | 97.61 |

FIGURE 1.

Phylogenetic relationships based on 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis of members of the bacterial communities associated with Aedes albopictus. In the cases where no published mosquito-derived sequences belonging to the same bacterial species were available, the closest hit deriving from mosquitos and the closest hit regardless of origin were included (to avoid misinterpretation of results). Evolutionary distances were calculated using the method of Jukes and Cantor and the topology was inferred using the neighbor-joining method. A representative isolate per each phylotype with their taxonomy assigned is indicated in the outer circle while the number of isolates is graphically represented. The 16S rRNA gene sequence of Chloroflexus aurantiacus was arbitrarily chosen as outgroup.

Although the initial selection of colonies from all three microbiological media was based on morphological criteria and only up to 20 colonies per sample were selected, it’s still worth noting the following: (a) representatives of nine genera were isolated from LAR samples while only one bacterial strain, Elizabethkingia sp., was isolated from 14DM; (b) some genera were represented by multiple representatives (in some cases, they may represent different species); (c) some bacterial isolates were recovered from just a single developmental stage while others from multiple ones and (d) representatives of several bacterial genera were isolated from both mosquito and control samples including Acinetobacter sp., Bacillus sp., Cedecea sp., Elizabethkingia sp., Enterobacter sp., and Pseudomonas sp. isolates (Table 1).

16S rRNA Gene-Based Taxonomic Composition of Artificially Reared Aedes albopictus

The sequence data obtained for the two targeted regions of the 16S rRNA gene (amplified by the primer pairs U341F/805R and 909F/1391R) were compared in selected samples and no statistically significant differences were observed (Supplementary Figures 1–5). For this reason, all results presented below and in the respective figures and tables have been prepared by combining the raw data of the two 16S rRNA gene regions.

In total, seven samples (EGG, LAR, 1DM, 1DF, 14DM, NBF, and BFF with three replicates each) were sequenced producing 546,136 reads for bioinformatic analysis with an average of 78,014 reads per sample (Table 2). Based on alpha-diversity indices, the larval samples were the most species rich in Ae. albopictus (Table 2). Males and females fed with sucrose and/or blood together with the teneral females exhibited the lowest species richness and diversity indices (Table 2). Interestingly, teneral mosquitoes exhibited a sex specific differentiation (Table 2). Richness indices like Chao1 were within the range of the number of OTUs indicating, like the rarefaction analysis (Supplementary Figure 5), that sampling of each treatment has reached saturation, which was supported by the Good’s coverage index (Table 2). The dominant OTUs that were identified in the present study were classified into 5 phyla, 8 classes, 17 orders, 23 families, and 29 genera (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Richness and diversity estimation of the 16S rRNA gene libraries of Aedes albopictus through the amplicon sequence analysis.

|

Samples |

Number of OTUs | Good’s coverage | Number of reads |

Species richness indices |

Species diversity indices |

||||

| Stage/Sex | Age | Diet | Chao1 | ACE | Shannon | Simpson | |||

| Eggs | Eggs | BFA | 114.13 ± 7.30a | 0.998 | 111,107 | 138.37 ± 9.61a | 137.7 ± 9.38a | 2.57 ± 0.03a | 0.72 ± 0.007a |

| Larva | Larva | LLD | 318.13 ± 9.86b | 0.995 | 62,223 | 362.61 ± 9.45b | 363.9 ± 9.41b | 5.21 ± 0.15b | 0.91 ± 0.009b |

| Males | 1 days | Teneral | 142.47 ± 3.43c | 0.998 | 54,555 | 157.50 ± 3.68c | 157.45 ± 4.09c | 2.64 ± 0.05c | 0.64 ± 0.021c |

| Females | 1 days | Teneral | 61.20 ± 2.69d | 0.999 | 82,200 | 72.63 ± 3.65d | 69.97 ± 2.93d | 0.84 ± 0.06d | 0.17 ± 0.014d |

| Males | 14 days | Sucrose | 67.17 ± 7.61d | 0.999 | 101,620 | 76.74 ± 8.10d | 76.61 ± 7.47d | 2.22 ± 0.16e | 0.57 ± 0.044e |

| Females | 14 days | Sucrose | 61.57 ± 3.01d | 0.998 | 57,246 | 86.67 ± 4.72e | 81.43 ± 3.15e | 1.59 ± 0.13f | 0.50 ± 0.043e |

| Females | 14 days | Blood | 61.70 ± 2.29d | 0.998 | 77,145 | 81.27 ± 3.54e | 80.48 ± 3.32e | 1.02 ± 0.02g | 0.30 ± 0.002f |

For each diversity index, ANOVAs followed by the Tukey HSD test, (p < 0.05) were performed. Significant differences are indicated by different letters.

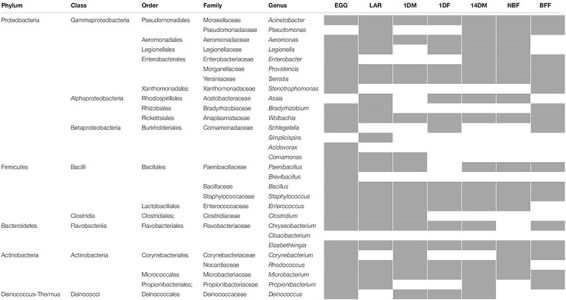

TABLE 3.

Taxonomic composition of the 16S rRNA gene sequencing data in the three analyzed populations.

|

Cells with a RA more than 1% they appear gray.

Our amplicon sequence analysis indicated that the EGG samples were dominated by Alphaproteobacteria (89.5%), mainly by Wolbachia, followed by Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes at 5.8% and 1% respectively (Figures 2A,B). In LAR samples, bacterial diversity was high and was evenly distributed between Bacteroidetes (31%), Firmicutes (28.8%), and Actinobacteria (20.8%), followed by Betaproteobacteria (10.6%), Gammaproteobacteria (6.8%), and Alphaproteobacteria (3.3%) (Figure 2A). The most dominant genera were those of Chryseobacterium, and Clostridium and to a lesser degree Microbacterium, Comamonas, Rhodococcus, and Acinetobacter (Figure 2B). The 1DM samples were dominated by Gammaproteobacteria (72%) followed by Alphaproteobacteria (16.6%), Firmicutes (4.3%), Actinobacteria (3%), Betaproteobacteria (2.2%), and Bacteroidetes (1%), while the 1DF samples were displaying a more even distribution between Gammaproteobacteria (31.1%), Firmicutes (32.2%), and Bacteroidetes (33.2%) (Figure 2A). This clear differentiation was also reflected at the genus level. The 1DM samples were dominated by Aeromonas sp. followed by Wolbachia and Serratia sp., while the 1DF samples were dominated by Elizabethkingia sp., Enterococcus sp. and Aeromonas sp. (Figure 2B). The 14DM samples, the bacterial diversity was evenly distributed between Gammaproteobacteria (30.4%), Alphaproteobacteria (28.8%), and Bacteroidetes (32.5%), followed by Firmicutes (5.1%) and Actinobacteria (2.6%) while the NBF exhibited a similar diversity but with the Gammaproteobacteria being abundant (62.4%) followed by Alphaproteobactreria (22.6%), and Bacteroidetes (13.1%) (Figure 2A). Interestingly, the BFF were almost exclusively dominated by Bacteroidetes (96.4%) (Figure 2A). At the genus level, the 14DM samples were characterized by the presence of Elizabethkingia sp. followed by Asaia sp., Serratia sp., Enterobacter sp., Providencia sp., and Wolbachia sp., the NBF samples were dominated by Serratia sp. and Asaia sp. followed by Elizabethkingia sp., while the BFF samples were dominated by Elizabethkingia sp., (95.4%) and Chryseobacterium sp. (0.94%) (Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Heatmaps of bacterial taxa identified by 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis in Aedes albopictus eggs (EGG), guts of larvae (LAR), and guts of 1-day old teneral males (1DM), 1-day old teneral females (1DF), 14-day old sugar-fed males (14DM), 14-day old sugar-fed females (NBF) and 14-day old blood-fed females (BFF). Taxa were grouped at (A) phylum level, except Proteobacteria that were grouped at the class level and (B) genus level. Cells with a RA less than 1% they appear empty.

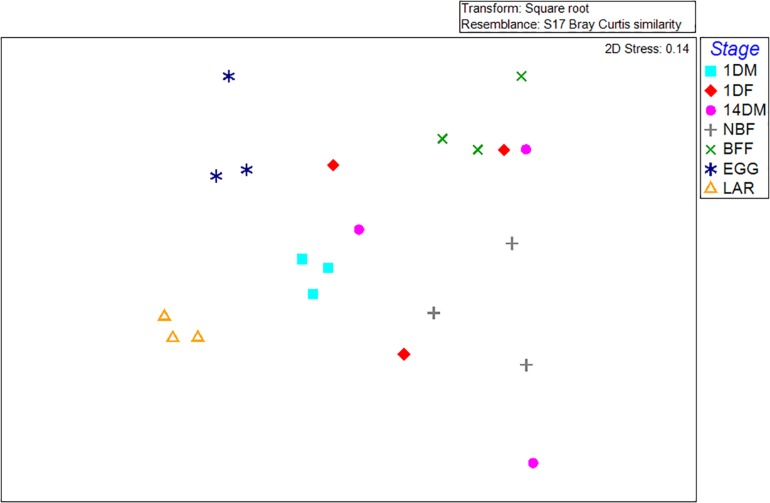

Non-metric multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) and principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) indicated that the samples examined were clustered mainly based on the developmental stage and the diet used (Figures 3, 4). In more detail, the clusters between eggs and larvae were statistically significant (PERMANOVA, P < 0.001), as were those between the guts of 1-day and 14-day old adults (PERMANOVA, P < 0.001). Interestingly, there was a statistically significant difference between the gut samples of 14-day old Ae. albopictus females fed with sucrose (NBF) or blood (BFF) (PERMANOVA, P < 0.001).

FIGURE 3.

Non-metric multidimensional scaling (MDS) plot based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarities visualizes differences in bacterial community structures according to age, developmental stage, sex and diet. Orange triangles inverted blue and cyan squares, red diamonds, pink circles, gray crosses, and green multiplication sign represent Aedes albopictus eggs (EGG), guts of larvae (LAR), and guts of 1-day old teneral males (1DM), 1-day old teneral females (1DF), 14-day old sugar-fed males (14DM), 14-day old sugar-fed females (NBF) and 14-day old blood-fed females (BFF), respectively.

FIGURE 4.

Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of bacterial communities based on the relative abundance of OTUs with ordinations from Aedes albopictus eggs (EGG), guts of larvae (LAR), and guts of 1-day old teneral males (1DM), 1-day old teneral females (1DF), 14-day old sugar-fed males (14DM), 14-day old sugar-fed females (NBF) and 14-day old blood-fed females (BFF). Variance explained by each PCoA axis is given in parentheses, while the main taxa that affect ordination clustering is presented.

Relative Density of Selected Bacterial Taxa During Aedes albopictus Development

Based on the NGS data, we selected some of the most abundant bacterial taxa, Aeromonas, Asaia, Chryseobacterium-Elizabethkingia groups, Enterococcus and Wolbachia, to investigate their relative density by qPCR (Figure 5 and Supplementary Table 3). The data clearly indicated that: (a) Wolbachia was dominant in the EGG samples and it could also be detected at lower densities in 1DM, 14DM, NBF and BFF samples (Tukey HSD, P < 0.0001); (b) Asaia was detected at higher densities in the NBF samples and at much lower densities in 14DM samples (Tukey HSD, P < 0.0001); (c) Aeromonas was detected in the 1DM samples and in one of the biological replicates of the 1DF samples (Tukey HSD, P = 0.0950); (d) the Elizabethkingia–Chryseobacterium group was present in high densities in BFF samples, and it was also detected in some biological replicates of the LAR, 1DF, 14DM as well as in the NBF samples; however, there was no statistically significant difference among the different groups (Tukey HSD, P = 0.0496). It is worth noting that, based on the NGS data, Elizabethkingia-Chryseobacterium was only detected in BFF, NBF, 14DM, 1DF but not in LAR, and (e) Enterococcus was detected at higher densities in one replicate of the 1DF samples and at lower densities in one replicate of the NBF samples (Tukey HSD, P = 0.0950).

FIGURE 5.

Relative abundance of five bacterial groups based on qPCR. (A) Wolbachia; (B) Asaia; (C) Aeromonas; (D) Elizabethkingia-Chryseobacterium group; (E) Enterococcus.

Discussion

By employing a cultivation-dependent and a cultivation-independent approach, significant information on the composition of gut-associated microbiota of lab-reared Ae. albopictus along developmental stages, sex and feeding regimes was obtained. Although our study provides useful information for a colonized population of an SIT targeted species, the results can not be generalized. However, this information can be used to improve the effectiveness of mosquito population control strategies such as SIT, IIT and others through, for example, the assessment of cultivable bacteria as potential probiotics to enhance the rearing efficiency and quality of mass-produced insects.

The Composition of Gut-Associated Microbiota of Lab-Reared Aedes albopictus

The cultivation-dependent approach resulted in the isolation of mosquito-associated bacteria which were assigned to 13 different genera (Table 1). The majority of them were Gram-negative, and mainly Gammaproteobacteria of the Enterobacteriaceae family, which have been previously described in other mosquito species such as Ae. triseriatus, An. albimanus, An. gambiae, An. stephensi, C. pipiens, C. quinquefasciatus, and C. tarsalis (Chao and Wistreich, 1959; Demaio et al., 1996; Pumpuni et al., 1996; Straif et al., 1998; Fouda et al., 2001; Gonzalez-Ceron et al., 2003; Pidiyar et al., 2004; Lindh et al., 2005), as well as in Ae. albopictus (Zouache et al., 2011; Otta et al., 2012; Minard et al., 2013b, 2014; Valiente Moro et al., 2013; Yadav et al., 2015), suggesting that they are widespread and constantly associated with mosquitoes.

Some gut-associated bacteria genera detected in the present study have been related with host’s biological process. Acinetobacter play a role in both blood digestion and nectar assimilation of Ae. albopictus (Minard et al., 2013b). Asaia may provide An. stephensi with vitamins (Crotti et al., 2010). Asaia and Elizabethkingia have been considered as candidates in paratransgenic approaches for mosquito control (Favia et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2015). Serratia and Enterobacter contain hemolytic enzymes and play a role in blood digestion of Ae. aegypti (Gaio et al., 2011). Serratia also play a role in chitin degradation of puparium (Iverson et al., 1984). However, S. marcescens was reported as pathogen of artificial-reared insects (Grimont and Grimont, 2015). As strains of Enterobacter have been proved candidates of probiotic for the Mediterranean fruit fly (Augustinos et al., 2015), isolation of these bacteria from Ae. albopictus provide potential material for further probiotic studying. Asaia played a specific role in the larval development of An. stephensi and reduced the developmental time before pupation (Crotti et al., 2010). It’s also worth noting that Cedecea spp. have been reported in the midgut of Psorophora columbiae (Demaio et al., 1996) and both field-collected and lab-reared An. gambiae (Pumpuni et al., 1996; Straif et al., 1998) while Cedecea spp. was also detected in the midgut of Ae. aegypti females (Gusmao et al., 2010). Interestingly, we isolated Cedecea spp. from larval guts as well from the egg surface of lab-reared Ae. albopictus suggesting a potential route for their inter-stadial transmission and these isolates may also represent potential probiotic candidates.

Previous studies in Anopheles showed lower diversity of gut-associated bacteria in lab-reared mosquitoes than wild populations (Gonzalez-Ceron et al., 2003; Rani et al., 2009). Klebsiella, which has been proven to be an effective probiotic of the Mediterranean fruit fly (Ben Ami et al., 2010; Gavriel et al., 2011; Kyritsis et al., 2017), has also been reported as a component of gut-associated bacterial communities in mosquitoes (Chao and Wistreich, 1960; Demaio et al., 1996; Straif et al., 1998; Terenius et al., 2012) including wild populations of Ae. albopictus (Crotti et al., 2009; Gusmao et al., 2010; Zouache et al., 2011; Valiente Moro et al., 2013; Yadav et al., 2015). However, this group was not detected in our study through both the cultivation-dependent and the cultivation-independent assays. Since there are documented differences among populations (Demaio et al., 1996; Zouache et al., 2011), this could be attributed to its absence from the original wild population. However, it could also be a result of a domestication process and the continuous artificial rearing. Similar to genetic changes, symbiotic changes may happen due to phenomena such as bottlenecks and small effective population size. Moreover, symbionts that are not crucial in the new environment may disappear and new may emerge, depending on the new rearing conditions.

Some of the bacterial isolates, such as Enterobacter, Cedecea (Enterobacteriaceae), Stenotrophomonas (Xanthomonadaceae), Pseudomonas (Pseudomonadaceae), and Staphylococcus (Staphylococcaceae) were not very abundant groups in NGS. It is well known that many factors including selectivity of culture-medium for specific bacterial taxa, growth rate and small colony number bias could influence the isolation process (Jannasch and Jones, 1959; Amann et al., 1995). NGS based culture-independent methods give relatively complete, albeit semi-quantitative, profile of the bacteria community. However, bias of Illumina could be induced too, for example, by PCR amplification protocols, primer choice and short read lengths (Claesson et al., 2010; Schloss et al., 2011; Pinto and Raskin, 2012; Tremblay et al., 2015; Gohl et al., 2016). It is interesting to note, however, that our NGS study provided similar Shannon diversity indices with those of previous studies which investigated either laboratory populations or populations of recent invasions and clearly lower when compared with that observed in established wild populations (Coon et al., 2016b; Hegde et al., 2018; Rosso et al., 2018). The bacterial profiles including the Aeromonas and Serratia co-occurrence pattern detected in the present study have also been previously observed (Hegde et al., 2018).

Impact of Sex, Age and Diet on Gut-Associated Bacteria

Our study clearly shows that there are differences between males and females, and age and diet may also contribute to these differences. Clustering analysis suggested that the effect of diet was more significant than that of sex. After the full digestion of blood meal, bacteria diversity decreased significantly in accordance with previous study in An. gambiae (Wang et al., 2011). Over 95% of the gut-associated bacteria were Elizabethkingia and Chryseobacterium, mostly the former one. This closely related group may possess a competitive advantage over the other bacteria. Elizabethkingia was dominant in the guts of both sugar-fed and blood-fed females (Wang et al., 2011). It has been reported that Elizabethkingia anophelis could contribute nutrients by participating in erythrocyte lysis in the mosquito midgut (Chen et al., 2015).

Among cultivable strains, Serratia could not be isolated after blood feeding, in contrast to Enterobacter and Pseudomonas. These genera have also been reported in field-caught female Anopheles and Culex mosquitoes (Gonzalez-Ceron et al., 2003; Pidiyar et al., 2004; Lindh et al., 2005; Rani et al., 2009; Chavshin et al., 2012). In wild-caught An. stephensi, Cryseobacterium, Pseudomonas and Serratia were identified only in females (Rani et al., 2009). Our results indicated that Pseudomonas and Enterobacter may be enhanced with blood meal in Ae. albopictus, and a similar observation has been made in An. gambiae (Wang et al., 2011). On the other hand, Serratia were relatively stable during the adult stage of Ae. albopictus females while in An. gambiae, it increased after blood meal and decreased later (Wang et al., 2011). Interestingly, Enterobacter sp. and Serratia sp. showed strong hemolytic activity among bacteria isolated from Ae. aegypti midgut while Serratia was found to be dominant in all isolations during blood digestion in the same species (Gaio et al., 2011) (Gusmao et al., 2010). It’s also worth noting that Azambuja and colleagues (Azambuja et al., 2004) isolated a S. marcescens strain which was able to lyse erythrocytes from guts of blood feeding Rhodnius prolixus. The nutrient composition of food sources was considered an explanation of the differential bacterial population structure between sexes (Minard et al., 2013b). Our results suggested that there was a strong effect of adult diet, like blood meal, on the structure of gut-associated bacterial communities.

Our study indicated that age also plays an important role in shaping the bacterial communities. For example, Wolbachia and Aeromonas were found at high densities in 1-day old males but their densities were drastically decreased in older males. On the other hand, the Elizabethkingia-Chryseobacterium group was essentially absent in young males and drastically increased in 14-days old males.

Dynamics and Trans-Stadial Transmission of Gut-Associated Bacteria Under Lab-Rearing Conditions

The present study identified several genera shared among control groups and mosquito samples. The isolates from larval food and sugar solution belonged to Acinetobacter, Bacillus, Enterobacter, Pseudomonas and Raoultella bacterial genera. In previous studies, Enterobacter sp. was shown to immigrate successfully in both larval and adult stages, Bacillus sp. to settle through food into larval guts whereas Raoultella sp. and Pseudomonas sp. to fail to settle in larval guts or to be maintained in a detectable level. In addition, the Acinetobacter sp. was found not only in mosquito guts but also in breeding sites and food sources (reviewed in Minard et al., 2013b).

Our study also provided a view of the bacterial dynamic among life stages of Ae. albopictus clearly indicating that gut-associated bacteria diversity changed significantly between eggs and larvae, teneral and 14-day old adults. Food (larval food, sugar solution, blood) is certainly a contributing factor for these changes and the transmission of some of these bacteria. Wolbachia, Asaia, and Elizabethkingia have been shown to pass on to eggs from parents (Kittayapong et al., 2002; Favia et al., 2007; Akhouayri et al., 2013). Gusmao and colleagues (Gusmao et al., 2010) identified Asaia sp. and Enterobacter sp. from Ae. aegypti eggs and considered them to be probably transovarially transmitted. Based on our NGS data, it was shown that Ae. albopictus eggs contained bacteria from more than 15 genera including Bacillus, Chryseobacterium and Escherichia-Shigella which were among the main groups in female adults both before and after blood feeding. Cedecea sp. and Elizabethkingia sp. were isolated from Ae. albopictus eggs and detected outside the eggs, suggesting that they are transmitted vertically via “egg smearing.” Akhouayri et al. (2013) externally treated embryos of An. gambiae with antiseptic solution and dramatically reduced the melanotic pathology which was caused by Elizabethkingia meningoseptica suggesting that it could be transmitted to embryos via “egg smearing.” In An. gambiae, one of the transmission routes of Asaia was also reported to be “egg smearing” (Damiani et al., 2010). Further studies are necessary to get knowledge on how these taxa are transmitted.

In conclusion, using culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches, we characterized mainly the microbiota associated with a laboratory strain of Ae. albopictus, which is reared under artificial rearing conditions for potential SIT-based applications, throughout the mosquito developmental stages (egg, larva and adult), at different adult ages (both young and old males and females) and female feeding regimes (sugar or blood). It is worth noting that a relatively high diversity of bacteria was detected in eggs (a stage understudied in mosquitoes), some of which were also found in adult females. Overall, our study clearly shows that developmental stage and diet are the key factors shaping the microbiota. The density levels of some of the most abundant taxa (Aeromonas, Asaia, Chryseobacterium-Elizabethkingia groups, Enterococcus, and Wolbachia) in different developmental stages and diets were determined by PCR. However, this should in the future be extended to other abundant bacterial taxa such as Serratia, Clostridium, and Providencia. Our study identified several species which may worth be investigated about their potential probiotic properties including members of the Enterobacteriaceae (Aeromonas, Elisabethkingia, Enterococcus, Enterobacter, Providencia) and Acetobacteriaceae (Asaia) families to enhance production and improve quality of mass-reared mosquito species which are to be used for SIT and other related population suppression programs.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the 16S rRNA gene sequences reported in this study have been deposited in NCBI under Bioproject number PRJNA575054, while the Sanger generated sequences have been deposited under accession numbers MN540103 to MN540125.

Author Contributions

SC performed the experiments and drafted the manuscript. DZ performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. AA performed the experiments and critically revised the manuscript. VD and NB performed the bioinformatic analysis and critically revised the manuscript. GT performed the bioinformatic analysis, interpreted the data, contributed to the drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. HM performed gut samples dissection and collection and critically revised the manuscript. KB conceived the study, designed the experiments, interpreted the data, contributed to the drafting, and critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jeremie Gilles for his overall support to this project.

Funding. This study was supported by the Joint FAO/IAEA Insect Pest Control Subprogramme. DZ was supported by the China Postdoctoral Innovation Program (BX20180394) and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2018M643317).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00605/full#supplementary-material

References

- Akami M., Andongma A. A., Zhengzhong C., Nan J., Khaeso K., Jurkevitch E., et al. (2019). Intestinal bacteria modulate the foraging behavior of the oriental fruit fly Bactrocera dorsalis (Diptera: Tephritidae). PLoS One 14:e0210109. 10.1371/journal.pone.0210109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhouayri I. G., Habtewold T., Christophides G. K. (2013). Melanotic pathology and vertical transmission of the gut commensal Elizabethkingia meningoseptica in the major malaria vector Anopheles gambiae. PLoS One 8:e77619. 10.1371/journal.pone.0077619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215 403–410. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amann R. I., Ludwig W., Schleifer K. H. (1995). Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol. Rev. 59 143–169. 10.1128/mmbr.59.1.143-169.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. J. (2001). A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral. Ecol. 26 32–46. 10.1046/j.1442-9993.2001.01070.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M. J., Willis T. J. (2003). Canonical analysis of principal coordinates: a useful method of constrained ordination for ecology. Ecology 84 511–525. 10.1890/0012-9658(2003)084 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arora A. K., Douglas A. E. (2017). Hype or opportunity? Using microbial symbionts in novel strategies for insect pest control. J. Insect. Physiol. 103 10–17. 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2017.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustinos A. A., Kyritsis G. A., Papadopoulos N. T., Abd-Alla A. M. M., Cáceres C., Bourtzis K. (2015). Exploitation of the medfly gut microbiota for the enhancement of sterile insect technique: use of Enterobacter sp. in larval diet-based probiotic applications. PLoS One 10:e0136459. 10.1371/journal.pone.0136459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azambuja P., Feder D., Garcia E. S. (2004). Isolation of Serratia marcescens in the midgut of Rhodnius prolixus: impact on the establishment of the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi in the vector. Exp. Parasitol. 107 89–96. 10.1016/j.exppara.2004.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balestrino F., Puggioli A., Gilles J. R. L., Bellini R. (2014). Validation of a new larval rearing unit for Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) mass rearing. PLoS One 9:e91914. 10.1371/journal.pone.0091914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Ami E., Yuval B., Jurkevitch E. (2010). Manipulation of the microbiota of mass-reared Mediterranean fruit flies Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) improves sterile male sexual performance. ISME J. 4 28–37. 10.1038/ismej.2009.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit J. B., Lopez-Martinez G., Patrick K. R., Phillips Z. P., Krause T. B., Denlinger D. L. (2011). Drinking a hot blood meal elicits a protective heat shock response in mosquitoes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 108 8026–8029. 10.1073/pnas.1105195108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yosef M., Behar A., Jurkevitch E., Yuval B. (2008). Bacteria-diet interactions affect longevity in the medfly Ceratitis capitata. J. Appl. Entomol. 132 690–694. 10.1111/j.1439-0418.2008.01330.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berasategui A., Shukla S., Salem H., Kaltenpoth M. (2016). Potential applications of insect symbionts in biotechnology. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100 1567–1577. 10.1007/s00253-015-7186-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum J. E., Fischer C. N., Miles J., Handelsman J. (2013). Frequent replenishment sustains the beneficial microbiome of Drosophila melanogaster. MBio 4:e0860-13. 10.1128/mBio.00860-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourtzis K., Lees R. S., Hendrichs J., Vreysen M. J. B. (2016). More than one rabbit out of the hat: radiation, transgenic and symbiont-based approaches for sustainable management of mosquito and tsetse fly populations. Acta Trop. 157 115–130. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourtzis K., Miller T. (eds) (2009). Insect Symbiosis 3. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bouyer J., Marois E. (2018). “Genetic control of vectors,” in Pests and Vector-Borne Diseases in the livestock Industry, eds Garros C., Bouyer J., Takken W., Smallegange R. C., (Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers; ), 435–451. [Google Scholar]

- Brady O. J., Gething P. W., Bhatt S., Messina J. P., Brownstein J. S., Hoen A. G., et al. (2012). Refining the global spatial limits of dengue virus transmission by evidence-based consensus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6:e1760. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z., Yao Z., Li Y., Xi Z., Bourtzis K., Zhao Z., et al. (2018). Intestinal probiotics restore the ecological fitness decline of Bactrocera dorsalis by irradiation. Evol. Appl. 11 1946–1963. 10.1111/eva.12698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso J. G., Bittinger K., Bushman F. D., DeSantis T. Z., Andersen G. L., Knight R. (2010a). PyNAST: a flexible tool for aligning sequences to a template alignment. Bioinformatics 26 266–267. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso J. G., Kuczynski J., Stombaugh J., Bittinger K., Bushman F. D., Costello E. K., et al. (2010b). QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7 335–336. 10.1038/nmeth.f.303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandel K., Mendki M. J., Parikh R. Y., Kulkarni G., Tikar S. N., Sukumaran D., et al. (2013). Midgut microbial community of Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito populations from India. PLoS One 8:e80453. 10.1371/journal.pone.0080453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao J., Wistreich G. A. (1959). Microbial isolations from the Mid-gut of Culex tarsalis coquillett. J. Insect Pathol. 1 311–318. [Google Scholar]

- Chao J., Wistreich G. A. (1960). Microorganisms from the midgut of larval and adult Culex quinquefasciatus Say. J. Insect Pathol. 2 220–224. [Google Scholar]

- Chavshin A. R., Oshaghi M. A., Vatandoost H., Pourmand M. R., Raeisi A., Enayati A. A., et al. (2012). Identification of bacterial microflora in the midgut of the larvae and adult of wild caught Anopheles stephensi: a step toward finding suitable paratransgenesis candidates. Acta Trop. 121 129–134. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.-G., Jiang X., Gu J., Xu M., Wu Y., Deng Y., et al. (2015). Genome sequence of the Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, reveals insights into its biology, genetics, and evolution. Proc. the Natl., Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 112 E5907–E5915. 10.1073/pnas.1516410112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou J.-H., Sheu S.-Y., Lin K.-Y., Chen W.-M., Arun A. B., Young C.-C. (2007). Comamonas odontotermitis sp. nov., isolated from the gut of the termite Odontotermes formosanus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57 887–891. 10.1099/ijs.0.64551-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouaia B., Rossi P., Epis S., Mosca M., Ricci I., Damiani C., et al. (2012). Delayed larval development in Anopheles mosquitoes deprived of Asaia bacterial symbionts. BMC Microbiol. 12 (Suppl. 1):S2. 10.1186/1471-2180-12-S1-S2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claesson M. J., Wang Q., O’Sullivan O., Greene-Diniz R., Cole J. R., Ross R. P., et al. (2010). Comparison of two next-generation sequencing technologies for resolving highly complex microbiota composition using tandem variable 16S rRNA gene regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 38:e200. 10.1093/nar/gkq873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon K. L., Brown M. R., Strand M. R. (2016a). Gut bacteria differentially affect egg production in the anautogenous mosquito Aedes aegypti and facultatively autogenous mosquito Aedes atropalpus (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasit. Vectors 9:375. 10.1186/s13071-016-1660-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon K. L., Brown M. R., Strand M. R. (2016b). Mosquitoes host communities of bacteria that are essential for development but vary greatly between local habitats. Mol. Ecol. 25 5806–5826. 10.1111/mec.13877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon K. L., Valzania L., McKinney D. A., Vogel K. J., Brown M. R., Strand M. R. (2017). Bacteria-mediated hypoxia functions as a signal for mosquito development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114 E5362–E5369. 10.1073/pnas.1702983114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coon K. L., Vogel K. J., Brown M. R., Strand M. R. (2014). Mosquitoes rely on their gut microbiota for development. Mol. Ecol. 23 2727–2739. 10.1111/mec.12771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crotti E., Damiani C., Pajoro M., Gonella E., Rizzi A., Ricci I., et al. (2009). Asaia, a versatile acetic acid bacterial symbiont, capable of cross-colonizing insects of phylogenetically distant genera and orders. Environ. Microbiol. 11 3252–3264. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02048.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crotti E., Rizzi A., Chouaia B., Ricci I., Favia G., Alma A., et al. (2010). Acetic acid bacteria, newly emerging symbionts of insects. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76 6963–6970. 10.1128/AEM.01336-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dame D. A., Loforen C., Ford H. R., Boston M. D., Baldwin K. F., Jeffery G. M. (1974). Release of chemosterilized males for the control of Anopheles albimanus in El Salvador. II. Methods of rearing, sterilization, and distribution. Am., J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 23 282–287. 10.4269/ajtmh.1974.23.282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damiani C., Ricci I., Crotti E., Rossi P., Rizzi A., Scuppa P., et al. (2010). Mosquito-bacteria symbiosis: the case of Anopheles gambiae and Asaia. Microb. Ecol. 60 644–654. 10.1007/s00248-010-9704-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demaio J., Pumpuni C. B., Kent M., Beier J. C. (1996). The midgut bacterial flora of wild Aedes triseriatus, Culex pipiens, and Psorophora columbiae mosquitoes. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 54 219–223. 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson L. B., Jiolle D., Minard G., Moltini-Conclois I., Volant S., Ghozlane A., et al. (2017). Carryover effects of larval exposure to different environmental bacteria drive adult trait variation in a mosquito vector. Sci. Adv. 3:e1700585. 10.1126/sciadv.1700585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon R. J., Dillon V. M. (2004). The gut bacteria of insects: nonpathogenic interactions. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 49 71–92. 10.1146/annurev.ento.49.061802.123416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas A. E. (2015). Multiorganismal insects: diversity and function of resident microorganisms. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 60 17–34. 10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 1792–1797. 10.1093/nar/gkh340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2010). Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26 2460–2461. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C., Haas B. J., Clemente J. C., Quince C., Knight R. (2011). UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27 2194–2200. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards U., Rogall T., Blöcker H., Emde M., Böttger E. C. (1989). Isolation and direct complete nucleotide determination of entire genes. Characterization of a gene coding for 16S ribosomal RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 17 7843–7853. 10.1093/nar/17.19.7843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel P., Moran N. A. (2013). The gut microbiota of insects - diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37 699–735. 10.1111/1574-6976.12025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favia G., Ricci I., Damiani C., Raddadi N., Crotti E., Marzorati M., et al. (2007). Bacteria of the genus Asaia stably associate with Anopheles stephensi, an Asian malarial mosquito vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 9047. 10.1073/pnas.0610451104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores H. A., O’Neill S. L. (2018). Controlling vector-borne diseases by releasing modified mosquitoes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16 508–518. 10.1038/s41579-018-0025-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Focks D. A. (1980). An improved separator for the developmental stages, sexes, and species of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 17 567–568. 10.1093/jmedent/17.6.567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster W. A. (1995). Mosquito sugar feeding and reproductive energetics. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 40 443–474. 10.1146/annurev.en.40.010195.002303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fouda M., Hassan M., Al-Daly A., Hammad K. (2001). Effect of midgut bacteria of Culex pipiens L. on digestion and reproduction. J. Egypti Soc. Parasitol. 31 767–780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaio A., de O., Gusmao D. S., Santos A. V., Berbert-Molina M. A., Pimenta P. F. P., et al. (2011). Contribution of midgut bacteria to blood digestion and egg production in aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) (L.). Parasit. Vectors 4:105. 10.1186/1756-3305-4-105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavriel S., Gazit Y., Yuval B. (2010). Effect of diet on survival, in the laboratory and the field, of sterile male Mediterranean fruit flies. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 135 96–104. 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2010.00972.x 15568345 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gavriel S., Jurkevitch E., Gazit Y., Yuval B. (2011). Bacterially enriched diet improves sexual performance of sterile male Mediterranean fruit flies. J. Appl. Entomol. 135 564–573. 10.1111/j.1439-0418.2010.01605.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gohl D. M., Vangay P., Garbe J., MacLean A., Hauge A., Becker A., et al. (2016). Systematic improvement of amplicon marker gene methods for increased accuracy in microbiome studies. Nat. Biotechnol. 34 942–949. 10.1038/nbt.3601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Ceron L., Santillan F., Rodriguez M. H., Mendez D., Hernandez-Avila J. E. (2003). Bacteria in midguts of field-collected Anopheles albimanus block Plasmodium vivax sporogonic development. J. Med. Entomol. 40 371–374. 10.1603/0022-2585-40.3.371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimont F., Grimont P. A. D. (2015). “Serratia,” in Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria, ed. Whitman W. B., (New York, NY: American Cancer Society; ), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Guegan M., Zouache K., Demichel C., Minard G., Tran Van V., Potier P., et al. (2018). The mosquito holobiont: fresh insight into mosquito-microbiota interactions. Microbiome 6:49. 10.1186/s40168-018-0435-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusmao D. S., Santos A. V., Marini D. C., Bacci M. J., Berbert-Molina M. A., Lemos F. J. A. (2010). Culture-dependent and culture-independent characterization of microorganisms associated with Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) (L.) and dynamics of bacterial colonization in the midgut. Acta Trop. 115 275–281. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamden H., Guerfali M. M., Fadhl S., Saidi M., Chevrier C. (2013). Fitness improvement of mass-reared sterile males of ceratitis capitata (Vienna 8 strain) (Diptera: Tephritidae) after gut enrichment with probiotics. J. Econ. Entomol. 106 641–647. 10.1603/EC12362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegde S., Khanipov K., Albayrak L., Golovko G., Pimenova M., Saldaña M. A., et al. (2018). Microbiome interaction networks and community structure from laboratory-reared and field-collected aedes aegypti, aedes albopictus, and Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito vectors. Front. Microbiol. 9:2160. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson K. L., Bromel M. C., Anderson A. W., Freeman T. P. (1984). Bacterial symbionts in the sugar beet root maggot, tetanops myopaeformis (von Röder). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 47 22–27. 10.1128/aem.47.1.22-27.1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jannasch H. W., Jones G. E. (1959). Bacterial populations in sea water as determined by different methods of enumeration1. Limnol. Oceanogr. 4 128–139. 10.4319/lo.1959.4.2.0128 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khaeso K., Andongma A. A., Akami M., Souliyanonh B., Zhu J., Krutmuang P., et al. (2018). Assessing the effects of gut bacteria manipulation on the development of the oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis (Diptera; Tephritidae). Symbiosis 74 97–105. 10.1007/s13199-017-0493-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kittayapong P., Baisley K. J., Sharpe R. G., Baimai V., O’Neill S. L. (2002). Maternal transmission efficiency of Wolbachia superinfections in Aedes albopictus populations in Thailand. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 66 103–107. 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Molina-Cruz A., Gupta L., Rodrigues J., Barillas-Mury C. (2010). A peroxidase/dual oxidase system modulates midgut epithelial immunity in Anopheles gambiae. Science 327 1644–1648. 10.1126/science.1184008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyritsis G. A., Augustinos A. A., Cáceres C., Bourtzis K. (2017). Medfly gut microbiota and enhancement of the sterile insect technique: similarities and differences of Klebsiella oxytoca and Enterobacter sp. AA26 probiotics during the larval and adult stages of the VIENNA 8D53+genetic sexing strain. Front. Microbiol. 8:2064. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees R. S., Gilles J. R., Hendrichs J., Vreysen M. J., Bourtzis K. (2015). Back to the future: the sterile insect technique against mosquito disease vectors. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 10 156–162. 10.1016/j.cois.2015.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindh J. M., Borg-Karlson A.-K., Faye I. (2008). Transstadial and horizontal transfer of bacteria within a colony of Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) and oviposition response to bacteria-containing water. Acta Trop. 107 242–250. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2008.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindh J. M., Terenius O., Faye I. (2005). 16S rRNA gene-based identification of midgut bacteria from field-caught Anopheles gambiae sensu lato and A. funestus mosquitoes reveals new species related to known insect symbionts. Appl. Environ, Microbiol. 71 7217–7223. 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7217-7223.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masella A. P., Bartram A. K., Truszkowski J. M., Brown D. G., Neufeld J. D. (2012). PANDAseq: paired-end assembler for illumina sequences. BMC Bioinform. 13:31. 10.1186/1471-2105-13-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minard G., Mavingui P., Moro C. V. (2013a). Diversity and function of bacterial microbiota in the mosquito holobiont. Parasit. Vectors 6:146. 10.1186/1756-3305-6-146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minard G., Tran F. H., Raharimalala F. N., Hellard E., Ravelonandro P., Mavingui P., et al. (2013b). Prevalence, genomic and metabolic profiles of Acinetobacter and Asaia associated with field-caught Aedes albopictus from Madagascar. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 83 63–73. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2012.01455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minard G., Tran F.-H., Dubost A., Tran-Van V., Mavingui P., Moro C. V. (2014). Pyrosequencing 16S rRNA genes of bacteria associated with wild tiger mosquito Aedes albopictus: a pilot study. Front. Cell.Infect. Microbiol. 4:59. 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minard G., Tran F.-H., Van V. T., Fournier C., Potier P., Roiz D., et al. (2018). Shared larval rearing environment, sex, female size and genetic diversity shape Ae. albopictus bacterial microbiota. PloS One 13:e0194521. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitraka E., Stathopoulos S., Siden-Kiamos I., Christophides G. K., Louis C. (2013). Asaia accelerates larval development of Anopheles gambiae. Pathog. Global Health 107 305–311. 10.1179/2047773213Y.0000000106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muturi E. J., Bara J. J., Rooney A. P., Hansen A. K. (2016). Midgut fungal and bacterial microbiota of Aedes triseriatus and Aedes japonicus shift in response to La Crosse virus infection. Mol. Ecol. 25 4075–4090. 10.1111/mec.13741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngwa C. J., Glockner V., Abdelmohsen U. R., Scheuermayer M., Fischer R., Hentschel U., et al. (2013). 16S rRNA gene-based identification of Elizabethkingia meningoseptica (Flavobacteriales: Flavobacteriaceae) as a dominant midgut bacterium of the Asian malaria vector Anopheles stephensi (Dipteria: Culicidae) with antimicrobial activities. J. Med. Entomol. 50 404–414. 10.1603/me12180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niyazi N., Lauzon C. R., Shelly T. E. (2004). Effect of probiotic adult diets on fitness components of sterile male Mediterranean fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) under laboratory and field cage conditions. J. Econ. Entomol. 97 1570–1580. 10.1603/0022-0493-97.5.1570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otta D. A., Rott M. B., Carlesso A. M., da Silva O. S. (2012). Prevalence of Acanthamoeba spp. (Sarcomastigophora: Acanthamoebidae) in wild populations of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasitol. Res. 111 2017–2022. 10.1007/s00436-012-3050-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang T., Mak T. K., Gubler D. J. (2017). Prevention and control of dengue-the light at the end of the tunnel. Lancet Infect. Dis. 17 e79–e87. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30471-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastoris M. C., Passi C., Maroli M. (1989). Evidence of Legionella pneumophila in some arthropods and related natural aquatic habitats. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 5 259–263. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1989.tb03700.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pidiyar V. J., Jangid K., Patole M. S., Shouche Y. S. (2004). Studies on cultured and uncultured microbiota of wild Culex quinquefasciatus mosquito midgut based on 16s ribosomal RNA gene analysis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 70 597–603. 10.4269/ajtmh.2004.70.597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto A. J., Raskin L. (2012). PCR biases distort bacterial and archaeal community structure in pyrosequencing datasets. PLoS One 7:e43093. 10.1371/journal.pone.0043093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pumpuni C. B., Demaio J., Kent M., Davis J. R., Beier J. C. (1996). Bacterial population dynamics in three anopheline species: the impact on Plasmodium sporogonic development. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 54 214–218. 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]