Abstract

During my postdoc interview in June of 1998, I asked Günter why he was moving more towards the nucleus in his latest studies. He said, “Well Joe, that’s where everything starts.” By the end of the interview, I accepted the postdoc. He had a way of making everything sound so cool. Günter’s progression was natural, since the endoplasmic reticulum and the nucleus are the only organelles that share the same membrane. The nuclear envelope extends into a double membrane system with Nuclear Pore Complexes embedded in the pore membrane openings. Even while writing this review, I remember Günter stressing; it is the Nuclear Pore Complex. Just saying Nuclear Pore doesn’t encompass the full magnitude of its significance. The Nuclear Pore Complex is one of the largest collection of proteins that fit together for an overall function: transport. This review will cover the Blobel lab contributions in the quest for the blueprint of the Nuclear Pore Complex from isolation of the nuclear envelope and nuclear lamin to the ring structures.

Keywords: Blobel, Nuclear Pore Complex, NPC, Nuclear Envelope, Nucleoporin, Nup, Pore Membrane, POM, Nuclear Lamin, Y-complex

Introduction

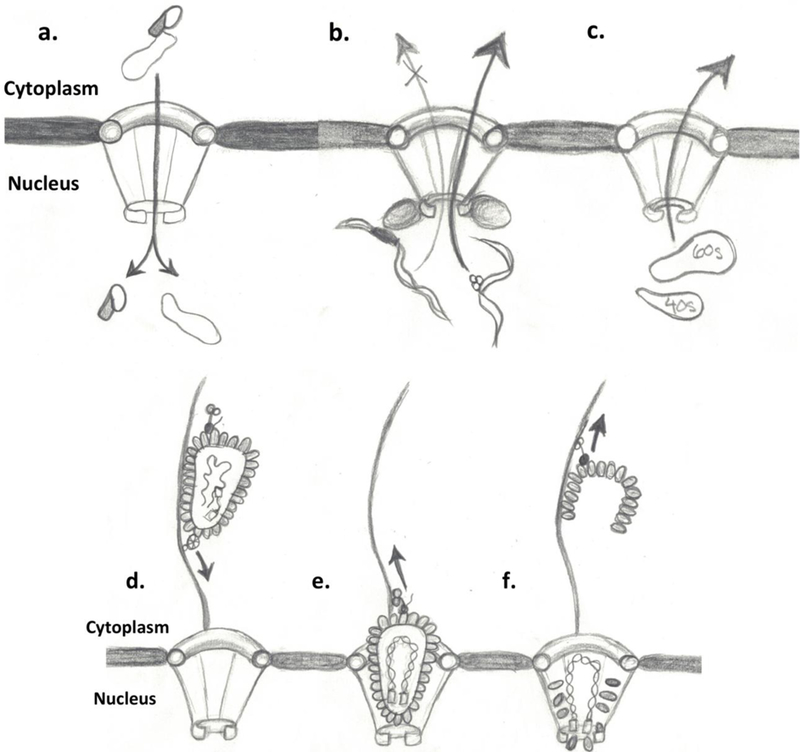

The nucleus and endoplasmic reticulum are the only organelles to share the same related membrane. The Nuclear Envelope (NE) is defined as a specialized endoplasmic reticulum membrane with a double bilayer containing inner and outer membrane systems [1]. While this separation protects the genome, it also is needed to organize nuclear entry and exit for basic cellular processes. The NE separates into three domains: the outer nuclear membrane (ONM), the inner nuclear membrane (INM) and the pore membrane (POM) [2,3]. The POM is the region of the NE where INM and ONM merge. The POM curvatures are coated with specific membrane proteins believed to anchor Nuclear Pore Complexes (NPCs) like the prongs of a diamond ring. NPCs, the gateways for macromolecular traffic into and out of the nucleus, are set in circular openings [4,2,5,6,3]. There are extremely regulated pathways that control nuclear entry and exit of molecules such as transcription factors, RNAs, kinases and viral particles. Overall, proteins with transport signal sequences to be imported or exported from the nucleus 1) bind to transport receptors, 2) are transported through an NPC and 3) translocate from the NPC to intranuclear or cytoplasmic target sites [7,4,8,9,5,3](Fig. 1a, see legend). Additional functions include recognition of properly spliced mRNA or ribosomal subunits for export (Fig. 1b–c). In addition, viruses exploit the NPC to passage into the nucleus from the cytoplasm [10,11]. Nuclear localization signal (NLS) can be collected from host proteins or contained within viral expressed proteins allowing for viral component translocation across NPCs (Fig. 1d–f, bottom panel)[12,13].

Fig. 1. Functions of the Nuclear Pore Complex (NPC).

Molecules smaller than 40 kDa can passively diffuse across the NPC but higher molecular weight proteins, a coordinated receptor-mediated transport to facilitate crossing into the nucleus [4,9,91,143–145]. Binding molecules, known as karyopherins (kaps), fasten to cargo in the cytosol and carry it into the nucleus (shown in panel a); in contrast, they bind cargo in the nucleus and deliver it to the cytoplasm. Kaps recognize their cargo by binding short amino acid sequence segments of the protein [146]. Cargos have nuclear localization signal (NLS) that are classically rich in basic residues for import (shaded area of protein in panel a) [4,9,147,146]. This form of transport is coupled to a cycle of GTP-binding and hydrolysis conducted through the protein Ran (not shown)[8]. The concentration of RanGTP is much higher in the nucleus. Therefore, once the complex has entered the nucleus, the high concentration allows for the disassembly and release of the components [9]. Another function of the NPC is to export properly spliced mRNA through recognition of spliced areas by recognition protein like MEX and TAP (panel b) and the export of ribosomal subunits from the nucleus (panel c). In bottom panels (d-f), viral transport through the NPC using microtubule network in combination with motor proteins like kinesin (panel d) lead to the docking of viral components to the NPC (panel e). Then translocation of viral genetic material and integration complexes into the nucleus (panel F) and disengaged viral coating traveling back up the microtubular network (panel f)[12,13](Pencil sketches courtesy of Grace Glavy).

Foundation for the Blueprint of the NPC

University of Wisconsin, Ph.D.: Van Potter’s Lab

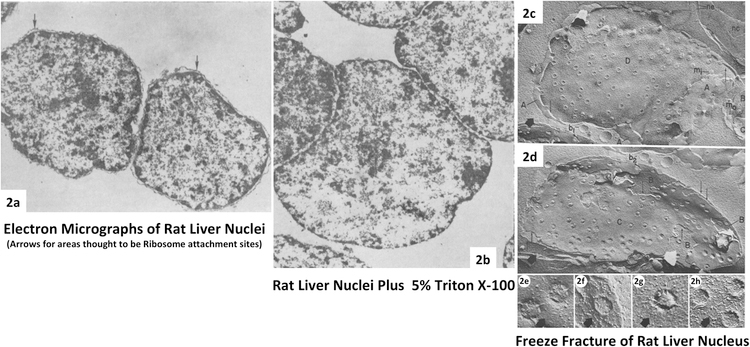

My labmates and I were discussing how one of Günter’s interns was taking a transatlantic cruise back to Germany and how wild that was; Günter interjected, “That’s how I arrived in New York.” Except he also brought his Volkswagen beetle on the ship and then drove it to Madison, Wisconsin for his medical research internship. Günter later decided to stay and pursue his Ph.D. in Van Potter’s laboratory at the University of Wisconsin. In 1966, Blobel and Van Potter described a protocol to generate a highly quantitative separation of nuclei from a homogenate of rat liver [14]. The rat liver offered a uniform population of cells containing nuclei. This protocol used concentrated sucrose solutions rather than detergents or citric acid which permitted better fractionation of cytoplasmic components while using certain parts of the Chauveau method [15–17] (Fig. 2a)[14]. To reduce contaminants seen with the Chauveau method, sucrose concentrations were raised to 2.3M. In the end, an estimated 91 percent of the nuclear DNA was recovered and nuclei contain 4.3 percent of the total RNA. Remnants of the ER with ribosomal attachment sites pointed out (Fig. 2a) were removed through low concentration treatment with Triton X-100 or deoxycholate and Tween 40 in Fig. 2b with little disruption to DNA content [14]. This work helped set the stage to isolate the NE and the nuclear matrix [18–31].

Fig. 2. Isolated Rat Liver Nuclei.

2a. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of isolated rat liver Nuclei, arrows identify residual ER ribosomal attachment sites. 2b. TEM of rat liver Nuclei after treatment with 5% Triton X-100 to eliminate ER and ribosomal attachment sites (Adapted from Blobel, G., Potter, VR. 1966 [14]). Freeze-cleaved preparation of rat liver nuclei, shown is the outer leaflet (2c)(Labeled as A&D within image) then the inner leaflet (2d) (Labeled as B&C within image). Bottom panel (2e-2h) arrows direct to corresponding NPC freeze fracture impressions. (Adapted from Monneron, A., Blobel, G., Palade, G.E. 1972 [26].

Rockefeller University, Post-Doc: George Palade’s Lab

In classic work in George Palade’s lab, freeze-cleaved preparations of nuclear fractions showed the two membrane configuration of the NE indicated in Fig. 2c [26]. In Fig. 2c, the face of the inner leaflet is marked as A (Fig. 2c), the complementary outer leaflet is marked as B (Fig. 2d) [26]. Higher magnification craters embedded in the double membrane [26]. These noted polygonal impressions in the NE are individual NPCs (bottom panel 2e-2h)[26,32,33,6,34]. The pores were referred to as circumvallate papillae like structures with long whiskers and found to have a mostly octagonal conformation [26,32,33]. Fractionation of nuclear component was enhanced by selective exposure to charged molecules [26]. Different concentrations of MgCl2 could uncover the different layers of the NE by competing with ionic interactions [26]. It was thought that with increasing concentrations and combinations of divalent cations, one could tear down the structure leading to ghost pores [35].

Principal Investigator: Rockefeller University

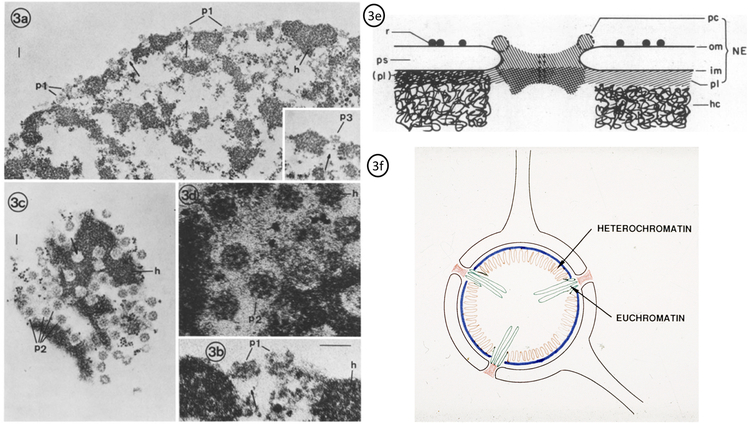

One of the first papers from the Blobel lab dealt with the attachment of the NPC. It was found that envelope-denuded nuclei (partially stripped of membrane) still retained their shape and NPCs maintained their position (Fig. 3a–b (NPCs), p1). After 2% Triton X-100 treatment, the eight-fold symmetry is clearly visible with distinct features (Fig. 3c–d, p2)[36,27,28,37]. The isolated NPCs from several different species maintain this octagonal configuration [38–43]. This arrangement may be necessary to ensure transport clearance for large protein complexes such as ribosomal subunits. Triton X-100 treatments greatly reduced phospholipids in the final pellets. DNA content and histone concentrations were not significantly affected. Early studies of the NE and NPC were ineffective in eliminating DNA and lamina. In later studies the addition of DNAse I digestion steps [44,29] reduced DNA content and revealed lamina connections to NPCs. Triton X-100 treatment followed by salt treatment led to the extraction of lamina-NPC fractions with little DNA/RNA and/or histone content [29,27]. NPCs remained intact and attached to lamina as seen by EM [29]. An early schematic diagram of the nuclear periphery lists the basic components as nuclear envelope, NE; NPC, pc; outer nuclear membrane, om; perinuclear space, ps; inner nuclear membrane, im; peripheral lamina, pl; heterochromatin, hc and ribosomes, r (Fig. 3e)[29]. The NE could be mapped as three distinct structures: the double membrane system, NPCs, and peripheral lamina [29,27], all separate from the nuclear matrix, which is the network of fibres found inside the cell nucleus. Further refinement of the NE was initially achieved through multiple DNAse digestion at pH 8.5 then pH 7.5 (further removal of histones observed) followed by Triton X-100 treatment and salt treatments [36]. Mild sonication led to laminar fragmentation with NPCs remaining intact [36]. Development of anti-sera against the lamina fractions allowed for accuracy while characterizing NE preparations [45]. Through reduction and alkylation, three distinct proteins between 60 and 70 kilodaltons were separated and used to produce an antiserum against each [45]. Later identified as lamin A/C and lamin B, these antisera produced nuclear staining with slight cytoplasmic background in some cases [45–49]. Lamin A/C was found depolymerized during mitosis while lamin B retained attachment to membrane or membrane fragments [46,50]. Intermediate filaments were found to attach to the lamins through studies focused on vimentin and desmin attachments [51,52]. Binding studies with radioactive lamin B labeled its receptor and attachment point to the NE [49,53]. In 1985, Günter proposed the “Gene Gating” hypothesis in PNAS (Fig. 3f) which postulates the idea that transcribed genes are positioned in close proximity to NPCs thereby stream-lining mRNA export [54]. From this early electron microscopy (EM), the position of euchromatin “active/open” and heterochromatin “inactive/closed” could be observed (Fig. 3f). Due to this relationship, NPCs potentially play a role in the adjustment of genomic structure corresponding to different stages in development, differentiation, and the cell cycle. NPCs are proposed as gene gating organelles capable of interacting specifically with expressing genes [54]. All transcripts of a specific gene are projected to exit the nucleus via the NPC to which the gene is gated [54]. The orderly distribution of NPC may reflect underlying genomic organization. Additionally, the nuclear lamin is proposed to participate in organization of compacted regions of the genome [54].

Fig. 3. Eight-fold Symmetry of NPCs.

The periphery of isolated rat liver nuclei after treatment with 2% Triton X-100 (a & b). Panels c & d demonstrate eight-fold symmetry of NPCs. (e) Schematic diagram of the nuclear periphery, lists the basic components as nuclear envelope, NE; the nuclear pore complex, pc; outer nuclear membrane, om; perinuclear space, ps; inner nuclear membrane, im; peripheral lamina, pl; heterochromatin, hc and ribosomes, r. (Adapted from Aaronson, RP., Blobel, G. 1974 & Aaronson, RP., Blobel, G. 1975 [28,29]). (f) Schematic diagram of the position of euchromatin “active/open” and heterochromatin “inactive/closed” relative to NPCs. NPCs are proposed as gene gating organelles capable of interacting specifically with expressing genes [54](Gift from Günter Blobel).

Nucleoporins: Proteins of the NPC.

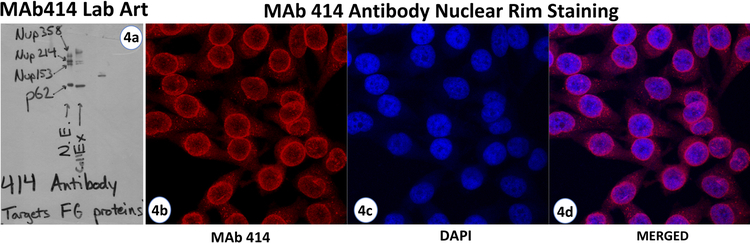

The proteins composing the NPC were termed nucleoporins (Nups) in 1986 and initially discovered by immune approaches similar to the nuclear lamina. Each NPC contains eight subunits or spokes (Fig. 3 c & d)[37,28,29]. By injection of the Triton X-100 treated rat liver nuclei into a BALB/c mouse, followed by spleen excision and fusion to hybridoma [55,56], a panel of monoclonal antibodies was produced against the nuclear components. Screens of this panel revealed a number of NPC reactive antibodies, none better than clone number 414 (Mab414)[55,56]. Initial studies revealed a specific recognition of a protein at 62 kilodaltons. Initially called p62 but later referenced as Nup62 for its membership as nuclear pore protein and molecular weight (Fig. 4A)[55,56]. This is the major theme of the nomenclature: Nup classification followed by kilodalton weight (Fig. 4A, MAb Lab Art). Of the reactive antibody clones, MAb414 gave a very clear NE or nuclear rim staining by immunofluorescence (Fig. 4B). This landmark study produced the gold standard antibody for decades. While the initial discovery was Nup62, MAb414 recognized more Nups. Nups: 358, 214, 153 and 62 all reacted (Fig. 4A). This was the reason for such pronounced nuclear rim staining, not one Nup but four. Our MAb Lab Art (western blot from my lab’s refrigerator door) answers the question before it’s asked, as MAb recognizes FG domains of these Nups (Fig. 4A). FG domains of Nup62 are used to further purify the antibody from ascites. Purified MAb414 immunoprecipitation in 2% Triton X-100 pulls down all four proteins plus Nup88, CRM1 and Karyopherin beta 1 as identified by mass spectrometry (Glavy, unpublished). A number of Nups have O-linked GlcNAc glycosylation including Nups: 358, 214, 153 and 62 (Fig. 4A). Through a combination of molecular genetics and immunoselection using the panel of monoclonal antibodies against Triton X-100 treated rat liver nuclei, several Nups were localized and isolated to begin characterization [57,58]. Immunoselection was achieved both by antibodies and glycoprotein recognition. Further work in the Blobel lab led to the identification of more Nups as well as pore membrane proteins (POM) both in yeast and human cells [57–64]. A procedure using wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) as a ligand binds a particular class of glycoprotein (N-Acetyl glucosamine groups or sialic acid residues) from the NPC-lamina fraction. Wheat germ agglutinins recognize sugar groups attached to amino acids of NE proteins, POM proteins, and Nups [59–64].

Fig. 4. MAb414 Lab Art-Western Analysis of MAb414.

4a. HeLa nuclear envelope preparation compared to cell extract. Lane 1: Heparin Treated HeLa Nuclear Envelope, labeled NE, Lane 2: HeLa cell extract (labeled Cell Ex). Proteins were separated on 4–20% SDS/PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose for western analysis probed with MAb414. Enriched NE clearly reacts with Nups 62, 153, 214, 358. Immunofluorescence Microscopy Analysis of MAb414. 4b-4d. HeLa cells were analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy. Labeled with MAb414 yielding a pronounced nuclear rim staining (red, 4b), Nucleus stained with DAPI (blue, 4c) and merged images (4d).

Although, officially, the Blobel lab only published one collaborative paper with the Brian Chait group at the Rockefeller on the cycle dependent phosphorylation of Y-Nups [65] this had a profound influence on the field because it led to many collaborations with former Blobel post docs with the Chait lab [66–69]. Through two separate studies, the composition of both the yeast and rat NPCs were inventoried [66–69]. In the case of rat liver nuclei preps, the isolated nuclei were subjected to a series of refined treatments [67,69]. The first step was the classic DNase/RNase digestion to eliminate nucleic acids [67,69]. This crude NE was then treated with low molecular weight heparin to further reduce DNA/histone content [67,69]. Next, enriched NE was subjected to Triton-X100 treatment allowing a NPC-lamina fraction to be isolated. This fraction was then solubilized with Emigen BB detergent (Zwitterionic, Amphoteric surfactant) [67,69]. The Chait lab used mass spectrometry (MS) to characterize the purified nucleoporin fraction [66–69]. C4-separated Emigen BB treated fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and stained bands were excised for tryptic digestion followed by mass spectrometric analysis. Mammalian NPCs contained at least seven novel Nups including ALADIN, Nup358, POM210, POM121, NDC1, Nup43, and Nup37 from yeast (Fig. 5)[67]. However results for both yeast and rat revealed approximately thirty Nups exist in both NPCs. These Nups are present in multiple copies, which added to the puzzle of this large transporter. Cloning of several Nups laid the foundation for structural studies leading to the investigations into the blueprint of the NPC.

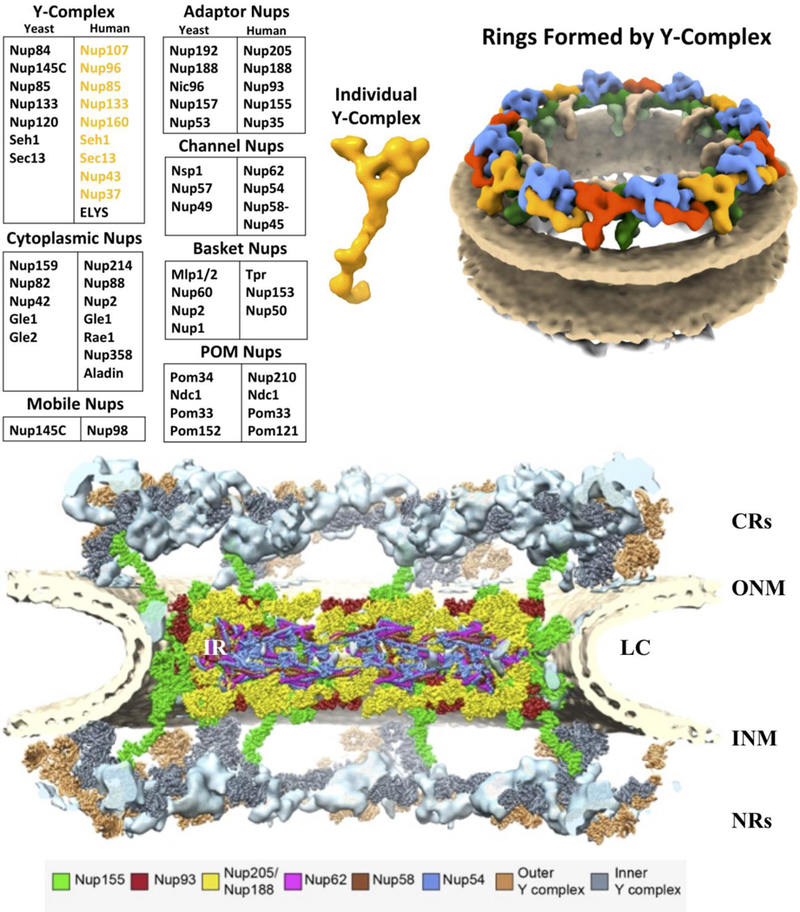

Fig. 5. Nucleoporin (Nups) Classification, Y-complex And Double Ring Structure.

Shown is the grouping of Nups for both yeast and human Nups (left panel)[3,1]. Structural model of individual Y-complex (middle panel, yellow). Human Double Ring structure formed by collections Y-complex dimers (red/blue and yellow/green)(right panel). [40].

The Quest

The NPC is a collection of a thousand proteins that form subunits leading to the overall structure (Fig. 5)[5,1,3]. The human NPC is approximately 110 MDa with a diameter of ≈60 nm and approximately 33 Nups [1,3,70]. As shown in Fig. 5, the Nups are sorted into 7 groups: Y-complex, Adaptor, Channel, Cytoplasmic, Basket, Mobile and POM. To help give a clearer beginning to the blueprint of the NPC, the stoichiometry was assessed by a mass spectrometry approach to calculate the copy number of individual Nups [71].

Y-complex:

Nup160, Nup133, Nup107, Nup96, Nup75, Nup43, Nup37, Seh1, and Sec13

Y-complex is the most abundant with nine members on the cytoplasmic side (human NPC: Nup160, Nup133, Nup107, Nup96, Nup75, Nup43, Nup37, Seh1, and Sec 13) and ten on the nuclear side with the addition of ELYS (Fig. 5)[72,73,5,3,65,74–77]. These Y-Nups can be pulled down both at G1 and mitosis as an intact unit [65]. Early negative-stained electron microscopy revealed a simple Y shape to this complex, which was later confirmed by Cryo-electron tomography (Cryo-ET) studies, hence the nomenclature [78,40,79]. The tenth member, ELYS, can be found under select conditions but is guaranteed to be crosslinked with the nuclear Y-complex [40,72,73]. ELYS is the only Y-complex protein found with a copy number of 16; the rest have 32. [71]. The complex is sometimes referred to as the coat nucleoporin complex (CNC)[76] as the Y-Nups form an imbricated ring structure of the NPC as shown in Fig. 5 [40]. Y-complexes within the ring are arranged in a head-to-tail fashion [43,40]. Sec13 is classified as a Y-complex member but has multiple locations and binding partners such Sec31 and Sec16 of the COPII vesicles in the ER and members of mTOR regulating SEA/GATOR2 complex [3,80,81]. The first crystal structure of the Y-complex from the Blobel lab was the N-terminus of Nup133 which possessed a seven bladed propeller [82]. Following structures from the Blobel lab (Nup107–133 [83], Nup107-Nup85-Nup96 [84], Nup85-Seh1 [85], and Nup96-Sec13 [86]) helped to begin to resolve the Y-complex configuration.

Adaptor Nups:

Nup93, Nup205, Nup188, Nup155, and Nup35

The Adaptor complex includes five members in humans: Nup93, Nup205, Nup188, Nup155, and Nup35 [87,41]. The X-ray crystal structure of Nup93 reveals an elongated, alpha-helical structure [88]. This form is evolutionarily conserved and therefore functionally maintained [88,89]. Members of the Adaptor complex contain mainly alpha-helical domains [88]. Nup93 and Nup155 are most abundant with 48 copies within the NPC [71]. The adaptor complex aids inner ring (IR) stabilization [88] and is needed for correct NPC assembly and homeostasis [88,89]. This has been confirmed by structure studies that Nup93 is a key component of the IR. Furthermore, Nup62 (Channel Nup) has been shown to interact with Nup93, illustrating interdependence between IR Nups and the Channel Nups [90]. Using an integrated approach (Fig. 6), we found in our studies that 32 copies of both Nup188 and Nup205 (yellow), Nup93 (red), Nup155 (green) and the Channel Nups (Next section: Nup:62, 58–45, 54) fit into the IR with additional Nup155 protein reaching up connecting to the outer ring (green). As shown in Fig. 6, the IRs comprise units similar to the Y-complex, suggesting their evolutionary connection [41], and resolving the ssubdomain of Nup205 and Nup188 and the asymmetric structures of Nup93 have been confirmed by structure studies to be a key component of the IR [41].

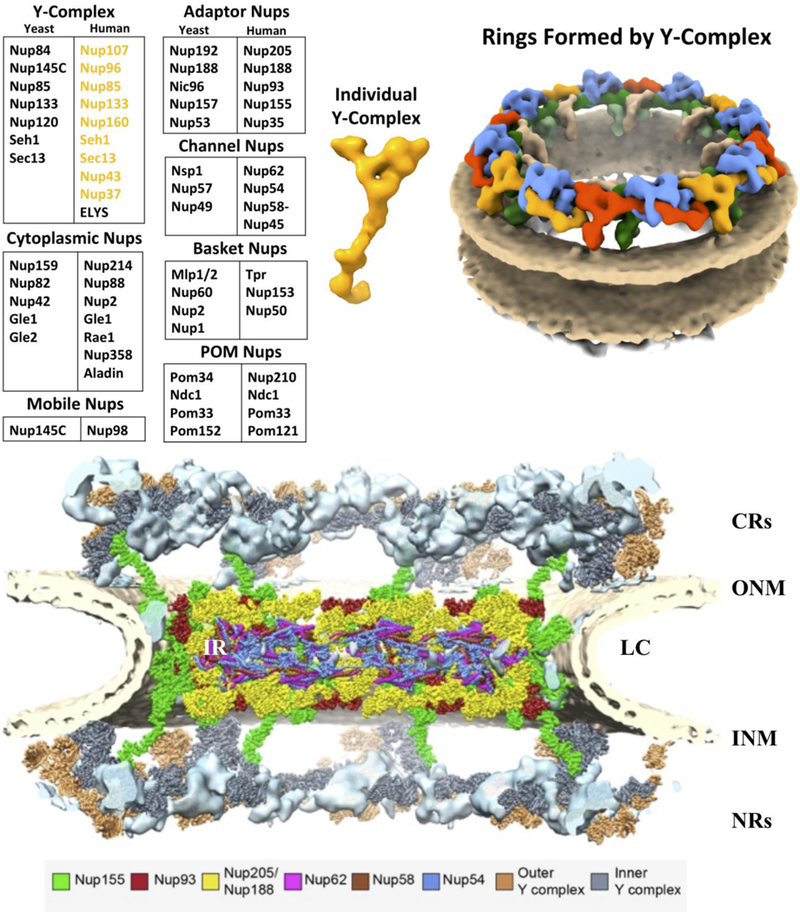

Fig. 6. Cross-section of the NPC.

NPC viewed from the cytosol side (top) to the nuclear side (bottom), structure is based on cryo-electron tomography (23Å)[41,40,43]. The curvature of the NE is shown: outer nuclear membrane (ONM), luminal curve (LC) and inner nuclear membrane (INM). The NPC is labeled: Inner Ring (IR) Cytoplasmic Rings (CRs) and Nuclear Ring (NRs)[41].

Channel Nups:

Nup62, Nup58-Nup45, and Nup54

Channel Nups have stretches of FG (Phe-Gly) repetitive residues, which are separated, by polar spacer regions of variable lengths [4,91–93]. FG repeat domains form unstructured regions that form weak interactions with transporting proteins called karyopherins (kaps)(Fig. 1)[4]. Channel Nups are located in the inner pore region or central core inner ring [39,38]. The complex includes Nup62, Nup58-Nup45, and Nup54 (Fig. 6)[94–96]. At one point this complex was referred to as the central plug region of the NPC. While these transport Nups line the inner NPC, it is unlikely that they form a plug against transport, but rather a dynamic transport area of the complex. The FG repeat domains form tentacle-like structures that emanate from and line the channel of the pore to form an FG barrier, which is highly disordered and dynamic [97,98]. In Fig. 6, they are shown to line the IR region. The crystal structure of Nup58-Nup45 produced by the Blobel lab displayed lateral displacements along the alpha-helical axes of their dimeric building blocks [95]. This gave rise to the hypothesis that this section of ring could slide and hence change the overall diameter [95]. Structural analysis of a larger Nup62–58-54 complex denied that sliding could occur while maintaining the trimeric structure [96]. Other channel Nups contain similar alpha-helical regions and may also slide [5], so questions still remain.

Nuclear Basket Nups:

Nup153, Nup50, and Tpr

Nup153 and Nup50 along with Tpr make up the nuclear basket and provide the surface to utilize binding areas for transport. Tpr (Translocated promoter region protein) is an unusual Nup (Nucleoporin Tpr) with more filament protein properties and is required for trafficking across the NE. Tpr coiled-coiled domains help give reliable support to form and maintain the nuclear basket [99]. A recent investigation implies that Tpr may be connected to the regulation of the total number of NPCs [100]. A mechanism for this regulation through extracellular signal– regulated kinases (ERK) pathways needs further investigation [100]. Tpr acts as a framework component in the nuclear segment and functions to tether chromatin. In addition, Tpr is anchored by Nup153 [101]. Tpr plays a role in mitotic spindle checkpoint signaling [102,103]. Furthermore, in concert with Nup153, it participates in both nuclear import and export pathways for proteins with or without nuclear export signal (NES) as well as the export of mRNA [102–104]. Within the nuclear basket, Nup153 is associated with Tpr and contains four zinc fingers. These zinc fingers increase the local Ran concentration to assist nuclear transport (167). Along with Nup50, Nup153 helps to terminate karyopherin mediated transport [4]. Nup153 provides the scaffold for Nup50 localization in the NPC [105].

Cytoplasmic Filament Nups:

Nup358, Nup214, Nup88, Nup2, Aladin, Rae1, and Gle1

As in the case of Channel Nups, Cytoplasmic Filament Nups possess FG regions. Their floppy tentacle nature is incompatible with crystal formation. Thus far, only non-FG regions of these Nups have been reported. The X-ray crystal structure of the non-FG repeat N-terminus of Nup214 reveals a seven bladed β-propeller with a segment of its C-terminus bound to the propeller [106]. Selective knockdown of Nup214 followed by Cryo-ET demonstrates that this subcomplex protrudes into the cytoplasmic ring region [40]. This position secures FG repeats onto the framework of the rings to facilitate nuclear transport [40]. Nup214, Nup88, and Gle1 interact with several Nups within the NPC. Nup358 is the largest Nup with multi-domain regions. It contains multiple Ran-binding domains including zinc finger domains and SUMO E3 ligase binding domains with many disordered areas mixed in [3,28]. The N-terminal alpha-helical domains serve as the anchor at the NPC while the C-terminus extends into the cytosol. Further application of gene-silencing/Cryo-ET uncovered a role for Nup358 to stabilize the cytoplasmic imbricated double ring structure [43]. These findings alter the once clear boundary concept between Y-complexes and Cytoplasmic filaments [43].

Mobile Nup:

Nup98

Nup98 is found both at NPC and within the nucleus [107–110,3]. It has multiple functions and binding partners [110,3,107]. Nup98 has roles in transport, mitotic progression, gene expression, epigenetic changes and viral infection [111–113,110,114,115]. It is not classified as a complex Nup with multiple locations along both sides of the NPC [107] and estimated to have a copy number of 48 within the human NPC [71]. Nup98 arises from a Nup98-Nup96 precursor form that splits by a self-cleavage domain similar to those found in Drosophila Hedgehog and Flavobacterium glycosylasparaginase [116,107]. This precursor gives rise to a mobile Nup (Nup98) and Y-complex Nup (Nup96). Yet to be explained is the fact that Nup96 is present in a different copy number of 32 [71].

The N-terminus of Nup98 contains FG repeats used as a docking site for kaps, but it not classified as an FG Nup but rather as a mobile Nup [107,108]. Nup98 ferries substrates between internuclear regions to NPCs, while regulating transcription of select genes implicated in development and growth [117–120,114,121]. Nup98 facilitates mRNA export from the nucleus [107,122]. Mitotic Phospho-Nup98 is a determining factor in NPC disassembly [119,120]. In NE breakdown (NEBD), the combination of phosphorylation and microtubule-based tearing are believed to lead to the resulting NEBD [123]. Several kinases lead to the hyperphosphorylation of Nup98 and Nup35 that may be contributing factors to NPC disassembly [119,124–128]. One of Nup98’s interacting partners is Rae1; together they act as temporal regulators of the anaphase-promoting complex [129]. Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) matrix (M) protein binds Nup98 and inhibits nuclear export of mRNA [122,130]. Studies suggest that Nup98 primes virus-stimulated genes to assist coordinating antiviral response [131].

Inhibition of Nup98 expression has been linked to impaired full expression of p21 and may regulate p53 [132]. Nup98 gene translocations have been linked to several forms of leukemia [114]. Chromosomal translocations involving Nup98 also alter expression of Nup96 [114,107]. Disrupted expression of Nup96 may serve as an additional contributing factor to disease phenotypes that arise from Nup98 translocations with transcription factors, as Nup96 plays a role in the regulation of export of mRNAs that are associated with immunity and cell cycle regulation [114,111,133]. Chromosome translocations of Nup98 are most frequently observed in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), chronic myeloid leukemia in blast crisis (CML-bc), and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) [134].

POM Nups:

gp210, Pom121, NDC1, and Pom33

The pore membrane (POM) curvature region of the NE is lined with select membrane proteins believed to anchor NPCs like the settings or prongs of a diamond ring [2,3]. POM Nup proteins are involved in the initiation of pore complex formation, stabilization, release and reformation of the NPC. To date, four POM Nups: gp210, Pom121, NDC1, and Pom33 have been classified through proteomic and genetic screenings. The largest POM protein, gp210 (Pom210), contains a single transmembrane domain as do the rest of the POM proteins. Gp210 was found to be essential for viability in HeLa cells [135]. Knockdowns of gp210 can trigger NE aberrant structures and NPC clusters [135].

NDC1 is found both in the POM region and the spindle pole body (SPB) during mitosis. It functions at the SPB, in yeast [136], helping to anchor the SPB at the NE, but in human cells its purpose is still unknown. RNAi experiments suggest a functional link between NE membrane NDC1 and members of the adaptor complex: Nup93 and Nup205 [137]. These results suggest an anchor point function for the Nup93 subcomplex [90]. The elimination of Pom121 results in the failure to assemble NPCs and to form continuous nuclear membranes [138]. XL-MS shows a direct linkage between Nup133 and Pom121 at the POM interface [40]. POM depletion studies point to the need for additional components to restore overall POM function[139]. NDC1 was shown to form a linkage between the NE and soluble Nups [140,137,139], and depletion of NDC1 shows markedly reduced Channel Nup staining compared to NDC1/control siRNA treatment [137,139].

The POM protein, Pom33 (TMEM33) is required for proper NPC distribution [141,142] as well as assembly. But a large percentage of Pom33 resides in the ER [142,141]. While an element of the tubular endoplasmic reticulum (ER) network, Pom33 also acts as a POM protein at NPCs [142,141]. The C-terminus of Pom33 contains several amphipathic regions that both bind to Kap123 and serve as attachment points that aid in positioning the POM region while N-terminal transmembrane regions anchor the POM [142].

EM and Cryo-ET Studies

Advances in a field are only possible with a solid foundation. Günter Blobel’s early work to isolate the NE helped lead to the characterization of the NPC. Even based on the first sets of EM images the eight-fold symmetry of the NPC was revealed (Fig.3) [28,29,38–43]. This eight-fold rotational symmetric structure is conserved across species [3,70]. The preserved arrangement may be related or proportional to conserved components of the cell such as preribosomal particle transport or perhaps the length and transport of mRNA or even related to the number of particles that can be transported at one time through the NPC. Although the symmetry remains, species differ in the layer construction of the entire NPC [3]. The NPC is a huge assemblage of proteins (110 MDa) making whole structure analyses a challenge [5,1,3]. Yet progress has been made through innovative techniques combining solid biochemistry/cell biology, proteomics, Cryo-ET and structural modelling.

Cytoplasmic Rings (CRs) and Nuclear Rings (NRs)

The Y-complex is a robust assembly [65,40]. For structural studies, the human Y-complex could be expressed from individual proteins to form a complex or the intact complex could be isolated [65,40,75,78]. It was reported in the Blobel lab that the Y-complex could be isolated as nine-member complex with minimal detergent application both at interphase and mitosis [65]. These properties were very advantageous for further analysis by crosslinking mass spectrometry (XL-MS) and structure analysis by Cryo-ET [40]. As shown in Fig. 5 (middle panel, yellow), the single Y-complex has two arms: long and short, leading to a stem region. The human Y-complexes form a basic element dimer of two shifted vertices (Fig. 5, dimers of Y-complexes, right panel, cytoplasmic side: red/blue dimer and yellow/green dimer) [40]. These elements, arranged in a head-to-tail conformation, assemble into two imbricated rings (Fig. 5, right panel), one each at the cytoplasmic side and the nuclear side of the NPC (Fig. 6. CR and NR)[40]. Nup358 RNAi perturbation experiments followed by structural modeling, found that Nup358 fastens the CRs to the NPC [43,40]. Reduction of Nup358 specifically affected CRs quantities [43] creating a hollow area in the rings. Only the Y-complex CRs, not the Y-complex NRs, were affected [43] both proving sidedness and the double ring structure. In the model organism, green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, the CRs contains only 8 copies of the Y-shape due to the lack of Nup358 [148]. This type of local interaction and conformations are most likely key to building an operational NPC.

Complexity of the Inner Ring (IR)

Based on our findings summarized in Fig. 6, the packing of the IR is by the assembly of channel and adaptor Nups. Within the IR, Nups 205,188, 93 and 155 integrate with the channel Nups [41]. Additionally Nup155 is set along the outer portions of the IR [41]. The IR comprises four core modules, each containing one copy of these channel and adaptor Nup combinations [41]. In the end, they come together through inter-complex interactions and oligomerize to form four horizontally stacked rings (Fig. 6.)[41]. The architectural principles are similar to the Y-complex of the outer rings of the CRs and NRs [41]. One of the fundamental hallmarks of this region is a membrane-binding coat of the NPC formed by the membrane engagement of the CR, NR and Nup155 [41]. Adaptor Nups 205 and 188 (Fig. 6, yellow) bind both to IR and Y-complex rings giving an interconnected stack of rings. Fig. 6 gives the current blueprint of the rings from top to bottom of the NPC. A key point of the structure is the combination of Nups in each ring and how they interlink between rings to form stacked layers. Not resolved or shown are the cytoplasmic Nups and the nuclear basket.

Summary

The combination of crystal structures (see recent review [3]) and cryo-ET reconstructions have made great advances in this quest for the blueprint of the NPC. Further studies will yield insights into the entire NPC structure. One vital area will be to elucidate the entire structure of the POM region and its role in the placement of the NPC. Next is to solve the structures of the components in the nuclear basket and cytoplasmic Nups. A method that will shed light on the regions of NPC is a combination of cryo-ET with selected knockdowns or knockouts of specific Nups [40,43]. Thus far, these advances were possible because of past experimentation. Günter Blobel’s work extended beyond the ER into the nucleus where everything starts. The separation of the nuclei to the point of intact NE set the stage to dive into structural studies. Günter’s endeavors led the way to study the NPC by individual crystal structures leading to further innovation and insights into the blueprint of the NPC.

Acknowledgments:

Much thanks goes to Thomas Cattabiani for critical reading and helpful discussions. The author is grateful to Grace Glavy, Michelle A. Veronin, Benjamin R. Jordan and Khanh Huy Bui for their contributions. And Günter Blobel for his influence.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Hoelz A, Glavy JS, Beck M (2016) Toward the atomic structure of the nuclear pore complex: when top down meets bottom up. Nat Struct Mol Biol 23 (7):624–630. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lusk CP, Blobel G, King MC (2007) Highway to the inner nuclear membrane: rules for the road. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8 (5):414–420. doi:nrm2165 [pii] 10.1038/nrm2165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin DH, Hoelz A (2019) The Structure of the Nuclear Pore Complex (An Update). Annu Rev Biochem 88:725–783. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-062917-011901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tran EJ, Wente SR (2006) Dynamic nuclear pore complexes: life on the edge. Cell 125 (6):1041–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoelz A, Debler EW, Blobel G (2011) The structure of the nuclear pore complex. Annu Rev Biochem 80:613–643. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060109-151030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gall JG (1954) Observations on the nuclear membrane with the electron microscope. Exp Cell Res 7 (1):197–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weis K (2003) Regulating access to the genome: nucleocytoplasmic transport throughout the cell cycle. Cell 112 (4):441–451. doi:S0092867403000825 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore MS, Blobel G (1993) The GTP-binding protein Ran/TC4 is required for protein import into the nucleus. Nature 365 (6447):661–663. doi: 10.1038/365661a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoelz A, Blobel G (2004) Cell biology: popping out of the nucleus. Nature 432 (7019):815–816. doi:432815a [pii] 10.1038/432815a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatch E, Hetzer M (2014) Breaching the nuclear envelope in development and disease. J Cell Biol 205 (2):133–141. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201402003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamauchi Y, Helenius A (2013) Virus entry at a glance. J Cell Sci 126 (Pt 6):1289–1295. doi: 10.1242/jcs.119685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strunze S, Engelke MF, Wang IH, Puntener D, Boucke K, Schleich S, Way M, Schoenenberger P, Burckhardt CJ, Greber UF (2011) Kinesin-1-mediated capsid disassembly and disruption of the nuclear pore complex promote virus infection. Cell Host Microbe 10 (3):210–223. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell EM, Hope TJ (2015) HIV-1 capsid: the multifaceted key player in HIV-1 infection. Nat Rev Microbiol 13 (8):471–483. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blobel G, Potter VR (1966) Nuclei from rat liver: isolation method that combines purity with high yield. Science 154 (3757):1662–1665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maggio R, Siekevitz P, Palade GE (1963) Studies on Isolated Nuclei. Ii. Isolation and Chemical Characterization of Nucleolar and Nucleoplasmic Subfractions. J Cell Biol 18:293–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maggio R, Siekevitz P, Palade GE (1963) Studies on Isolated Nuclei. I. Isolation and Chemical Characterization of a Nuclear Fraction from Guinea Pig Liver. J Cell Biol 18:267–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chauveau J, Moule Y, Rouiller C (1956) Isolation of pure and unaltered liver nuclei morphology and biochemical composition. Exp Cell Res 11 (2):317–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kashnig DM, Kasper CB (1969) Isolation, morphology, and composition of the nuclear membrane from rat liver. J Biol Chem 244 (14):3786–3792 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franke WW, Deumling B, Baerbelermen, Jarasch ED, Kleinig H (1970) Nuclear membranes from mammalian liver. I. Isolation procedure and general characterization. J Cell Biol 46 (2):379–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berezney R, Funk LK, Crane FL (1970) Electron transport in mammalian nuclei. II. Oxidative enzmes in a large-scale preparation of bovine liver nuclei. Biochim Biophys Acta 223 (1):61–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berezney R, Funk LK, Crane FL (1970) The isolation of nuclear membrane from a large-scale preparation of bovine liver nuclei. Biochim Biophys Acta 203 (3):531–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berezney R, Funk LK, Crane FL (1970) Nuclear electron transport. I. Electron transport enzymes in bovine liver nuclei and nuclear membrane. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 38 (1):93–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keenan TW, Berezney R, Funk LK, Crane FL (1970) Lipid composition of nuclear membranes isolated from bovine liver. Biochim Biophys Acta 203 (3):547–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ueda K, Matsuura T, Date N, Kawai K (1969) The occurrence of cytochromes in the membranous structures of calf thymus nuclei. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 34 (3):322–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zbarsky IB, Perevoshchikova KA, Delektorskaya LN, Delektorsky VV (1969) Isolation and biochemical characteristics of the nuclear envelope. Nature 221 (5177):257–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monneron A, Blobel G, Palade GE (1972) Fractionation of the nucleus by divalent cations. Isolation of nuclear membranes. J Cell Biol 55 (1):104–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scheer U, Kartenbeck J, Trendelenburg MF, Stadler J, Franke WW (1976) Experimental disintegration of the nuclear envelope. Evidence for pore-connecting fibrils. J Cell Biol 69 (1):1–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aaronson RP, Blobel G (1974) On the attachment of the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol 62 (3):746–754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aaronson RP, Blobel G (1975) Isolation of nuclear pore complexes in association with a lamina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 72 (3):1007–1011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berezney R (1974) Large-scale isolation of nuclear membranes from bovine liver. Methods Cell Biol 8 (0):205–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berezney R, Coffey DS (1974) Identification of a nuclear protein matrix. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 60 (4):1410–1417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watson ML (1954) Pores in the mammalian nuclear membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta 15 (4):475–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watson ML (1955) The nuclear envelope; its structure and relation to cytoplasmic membranes. J Biophys Biochem Cytol 1 (3):257–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patrizi G, Poger M (1967) The ultrastructure of the nuclear periphery. The zonula nucleum limitans. J Ultrastruct Res 17 (1):127–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diguilio AL, Glavy JS (2013) Depletion of nucleoporins from HeLa nuclear pore complexes to facilitate the production of ghost pores for in vitro reconstitution. Cytotechnology 65 (4):469–479. doi: 10.1007/s10616-012-9501-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dwyer N, Blobel G (1976) A modified procedure for the isolation of a pore complex-lamina fraction from rat liver nuclei. J Cell Biol 70 (3):581–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gall JG (1967) Octagonal nuclear pores. J Cell Biol 32 (2):391–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beck M, Forster F, Ecke M, Plitzko JM, Melchior F, Gerisch G, Baumeister W, Medalia O (2004) Nuclear pore complex structure and dynamics revealed by cryoelectron tomography. Science 306 (5700):1387–1390. doi:1104808 [pii] 10.1126/science.1104808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beck M, Lucic V, Forster F, Baumeister W, Medalia O (2007) Snapshots of nuclear pore complexes in action captured by cryo-electron tomography. Nature 449 (7162):611–615. doi:nature06170 [pii] 10.1038/nature06170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bui KH, von Appen A, Diguilio AL, Ori A, Sparks L, Mackmull MT, Bock T, Hagen W, Andres-Pons A, Glavy JS, Beck M (2013) Integrated structural analysis of the human nuclear pore complex scaffold. Cell 155 (6):1233–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kosinski J, Mosalaganti S, von Appen A, Teimer R, DiGuilio AL, Wan W, Bui KH, Hagen WJ, Briggs JA, Glavy JS, Hurt E, Beck M (2016) Molecular architecture of the inner ring scaffold of the human nuclear pore complex. Science 352 (6283):363–365. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf0643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beck M, Glavy JS (2014) Toward understanding the structure of the vertebrate nuclear pore complex. Nucleus 5 (2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.von Appen A, Kosinski J, Sparks L, Ori A, DiGuilio AL, Vollmer B, Mackmull MT, Banterle N, Parca L, Kastritis P, Buczak K, Mosalaganti S, Hagen W, Andres-Pons A, Lemke EA, Bork P, Antonin W, Glavy JS, Bui KH, Beck M (2015) In situ structural analysis of the human nuclear pore complex. Nature 526 (7571):140–143. doi: 10.1038/nature15381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kay RR, Fraser D, Johnston IR (1972) A method for the rapid isolation of nuclear membranes from rat liver. Characterisation of the membrane preparation and its associated DNA polymerase. Eur J Biochem 30 (1):145–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gerace L, Blum A, Blobel G (1978) Immunocytochemical localization of the major polypeptides of the nuclear pore complex-lamina fraction. Interphase and mitotic distribution. J Cell Biol 79 (2 Pt 1):546–566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gerace L, Blobel G (1980) The nuclear envelope lamina is reversibly depolymerized during mitosis. Cell 19 (1):277–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fisher DZ, Chaudhary N, Blobel G (1986) cDNA sequencing of nuclear lamins A and C reveals primary and secondary structural homology to intermediate filament proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 83 (17):6450–6454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Worman HJ, Lazaridis I, Georgatos SD (1988) Nuclear lamina heterogeneity in mammalian cells. Differential expression of the major lamins and variations in lamin B phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 263 (24):12135–12141 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Worman HJ, Yuan J, Blobel G, Georgatos SD (1988) A lamin B receptor in the nuclear envelope. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 85 (22):8531–8534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Georgatos SD, Blobel G (1987) Lamin B constitutes an intermediate filament attachment site at the nuclear envelope. J Cell Biol 105 (1):117–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Georgatos SD, Weber K, Geisler N, Blobel G (1987) Binding of two desmin derivatives to the plasma membrane and the nuclear envelope of avian erythrocytes: evidence for a conserved site-specificity in intermediate filament-membrane interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 84 (19):6780–6784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Djabali K, Portier MM, Gros F, Blobel G, Georgatos SD (1991) Network antibodies identify nuclear lamin B as a physiological attachment site for peripherin intermediate filaments. Cell 64 (1):109–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Appelbaum J, Blobel G, Georgatos SD (1990) In vivo phosphorylation of the lamin B receptor. Binding of lamin B to its nuclear membrane receptor is affected by phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 265 (8):4181–4184 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blobel G (1985) Gene gating: a hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 82 (24):8527–8529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davis LI, Blobel G (1986) Identification and characterization of a nuclear pore complex protein. Cell 45 (5):699–709. doi:0092-8674(86)90784-1 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Davis LI, Blobel G (1987) Nuclear pore complex contains a family of glycoproteins that includes p62: glycosylation through a previously unidentified cellular pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 84 (21):7552–7556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wente SR, Rout MP, Blobel G (1992) A new family of yeast nuclear pore complex proteins. J Cell Biol 119 (4):705–723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wente SR, Blobel G (1993) A temperature-sensitive NUP116 null mutant forms a nuclear envelope seal over the yeast nuclear pore complex thereby blocking nucleocytoplasmic traffic. J Cell Biol 123 (2):275–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Courvalin JC, Lassoued K, Bartnik E, Blobel G, Wozniak RW (1990) The 210-kD nuclear envelope polypeptide recognized by human autoantibodies in primary biliary cirrhosis is the major glycoprotein of the nuclear pore. J Clin Invest 86 (1):279–285. doi: 10.1172/JCI114696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wozniak RW, Blobel G (1992) The single transmembrane segment of gp210 is sufficient for sorting to the pore membrane domain of the nuclear envelope. J Cell Biol 119 (6):1441–1449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hallberg E, Wozniak RW, Blobel G (1993) An integral membrane protein of the pore membrane domain of the nuclear envelope contains a nucleoporin-like region. J Cell Biol 122 (3):513–521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Radu A, Blobel G, Wozniak RW (1993) Nup155 is a novel nuclear pore complex protein that contains neither repetitive sequence motifs nor reacts with WGA. J Cell Biol 121 (1):1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kraemer D, Wozniak RW, Blobel G, Radu A (1994) The human CAN protein, a putative oncogene product associated with myeloid leukemogenesis, is a nuclear pore complex protein that faces the cytoplasm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91 (4):1519–1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Radu A, Blobel G, Wozniak RW (1994) Nup107 is a novel nuclear pore complex protein that contains a leucine zipper. J Biol Chem 269 (26):17600–17605 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Glavy JS, Krutchinsky AN, Cristea IM, Berke IC, Boehmer T, Blobel G, Chait BT (2007) Cell-cycle-dependent phosphorylation of the nuclear pore Nup107–160 subcomplex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 (10):3811–3816. doi:0700058104 [pii] 10.1073/pnas.0700058104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rout MP, Aitchison JD, Suprapto A, Hjertaas K, Zhao Y, Chait BT (2000) The yeast nuclear pore complex: composition, architecture, and transport mechanism. J Cell Biol 148 (4):635–651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cronshaw JM, Krutchinsky AN, Zhang W, Chait BT, Matunis MJ (2002) Proteomic analysis of the mammalian nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol 158 (5):915–927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rout MP, Blobel G (1993) Isolation of the yeast nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol 123 (4):771–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Matunis MJ (2006) Isolation and fractionation of rat liver nuclear envelopes and nuclear pore complexes. Methods 39 (4):277–283. doi:S1046–2023(06)00094–6 [pii] 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.von Appen A, Beck M (2016) Structure Determination of the Nuclear Pore Complex with Three-Dimensional Cryo electron Microscopy. J Mol Biol 428 (10 Pt A):2001–2010. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ori A, Banterle N, Iskar M, Andres-Pons A, Escher C, Khanh Bui H, Sparks L, Solis-Mezarino V, Rinner O, Bork P, Lemke EA, Beck M (2013) Cell type-specific nuclear pores: a case in point for context-dependent stoichiometry of molecular machines. Mol Syst Biol 9:648. doi: 10.1038/msb.2013.4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rasala BA, Orjalo AV, Shen Z, Briggs S, Forbes DJ (2006) ELYS is a dual nucleoporin/kinetochore protein required for nuclear pore assembly and proper cell division. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103 (47):17801–17806. doi:0608484103 [pii] 10.1073/pnas.0608484103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Franz C, Walczak R, Yavuz S, Santarella R, Gentzel M, Askjaer P, Galy V, Hetzer M, Mattaj IW, Antonin W (2007) MEL-28/ELYS is required for the recruitment of nucleoporins to chromatin and postmitotic nuclear pore complex assembly. EMBO Rep 8 (2):165–172. doi:7400889 [pii] 10.1038/sj.embor.7400889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cristea IM, Williams R, Chait BT, Rout MP (2005) Fluorescent proteins as proteomic probes. Mol Cell Proteomics 4 (12):1933–1941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kampmann M, Blobel G (2009) Three-dimensional structure and flexibility of a membrane-coating module of the nuclear pore complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16 (7):782–788. doi:nsmb.1618 [pii] 10.1038/nsmb.1618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lin DH, Stuwe T, Schilbach S, Rundlet EJ, Perriches T, Mobbs G, Fan Y, Thierbach K, Huber FM, Collins LN, Davenport AM, Jeon YE, Hoelz A (2016) Architecture of the symmetric core of the nuclear pore. Science 352 (6283):aaf1015. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stuwe T, Correia AR, Lin DH, Paduch M, Lu VT, Kossiakoff AA, Hoelz A (2015) Nuclear pores. Architecture of the nuclear pore complex coat. Science 347 (6226):1148–1152. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lutzmann M, Kunze R, Buerer A, Aebi U, Hurt E (2002) Modular self-assembly of a Y-shaped multiprotein complex from seven nucleoporins. Embo J 21 (3):387–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Siniossoglou S, Lutzmann M, Santos-Rosa H, Leonard K, Mueller S, Aebi U, Hurt E (2000) Structure and assembly of the Nup84p complex. J Cell Biol 149 (1):41–54. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.1.41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dokudovskaya S, Waharte F, Schlessinger A, Pieper U, Devos DP, Cristea IM, Williams R, Salamero J, Chait BT, Sali A, Field MC, Rout MP, Dargemont C (2011) A conserved coatomer-related complex containing Sec13 and Seh1 dynamically associates with the vacuole in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Proteomics 10 (6):M110 006478. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.006478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dokudovskaya S, Rout MP (2011) A novel coatomer-related SEA complex dynamically associates with the vacuole in yeast and is implicated in the response to nitrogen starvation. Autophagy 7 (11):1392–1393. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.11.17347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Berke IC, Boehmer T, Blobel G, Schwartz TU (2004) Structural and functional analysis of Nup133 domains reveals modular building blocks of the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol 167 (4):591–597. doi:jcb.200408109 [pii] 10.1083/jcb.200408109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Boehmer T, Jeudy S, Berke IC, Schwartz TU (2008) Structural and functional studies of Nup107/Nup133 interaction and its implications for the architecture of the nuclear pore complex. Mol Cell 30 (6):721–731. doi:S1097–2765(08)00325–0 [pii] 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nagy V, Hsia KC, Debler EW, Kampmann M, Davenport AM, Blobel G, Hoelz A (2009) Structure of a trimeric nucleoporin complex reveals alternate oligomerization states. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106 (42):17693–17698. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909373106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Debler EW, Ma Y, Seo HS, Hsia KC, Noriega TR, Blobel G, Hoelz A (2008) A fence-like coat for the nuclear pore membrane. Mol Cell 32 (6):815–826. doi:S1097–2765(08)00840-X [pii] 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hsia KC, Stavropoulos P, Blobel G, Hoelz A (2007) Architecture of a coat for the nuclear pore membrane. Cell 131 (7):1313–1326. doi:S0092–8674(07)01542–5 [pii] 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hawryluk-Gara LA, Shibuya EK, Wozniak RW (2005) Vertebrate Nup53 interacts with the nuclear lamina and is required for the assembly of a Nup93-containing complex. Mol Biol Cell 16 (5):2382–2394. doi:E04–10-0857 [pii] 10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jeudy S, Schwartz TU (2007) Crystal structure of nucleoporin Nic96 reveals a novel, intricate helical domain architecture. J Biol Chem 282 (48):34904–34912. doi:M705479200 [pii] 10.1074/jbc.M705479200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stuwe T, Lin DH, Collins LN, Hurt E, Hoelz A (2014) Evidence for an evolutionary relationship between the large adaptor nucleoporin Nup192 and karyopherins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111 (7):2530–2535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311081111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Antonin W, Ellenberg J, Dultz E (2008) Nuclear pore complex assembly through the cell cycle: regulation and membrane organization. FEBS Lett 582 (14):2004–2016. doi:S0014–5793(08)00190–7 [pii] 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.02.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lim RY, Aebi U, Fahrenkrog B (2008) Towards reconciling structure and function in the nuclear pore complex. Histochem Cell Biol 129 (2):105–116. doi: 10.1007/s00418-007-0371-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kita K, Omata S, Horigome T (1993) Purification and characterization of a nuclear pore glycoprotein complex containing p62. J Biochem 113 (3):377–382. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Strawn LA, Shen T, Shulga N, Goldfarb DS, Wente SR (2004) Minimal nuclear pore complexes define FG repeat domains essential for transport. Nat Cell Biol 6 (3):197–206. doi: 10.1038/ncb1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schwartz TU (2005) Modularity within the architecture of the nuclear pore complex. Curr Opin Struct Biol 15 (2):221–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Melcak I, Hoelz A, Blobel G (2007) Structure of Nup58/45 suggests flexible nuclear pore diameter by intermolecular sliding. Science 315 (5819):1729–1732. doi:315/5819/1729 [pii] 10.1126/science.1135730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chug H, Trakhanov S, Hulsmann BB, Pleiner T, Gorlich D (2015) Crystal structure of the metazoan Nup62*Nup58*Nup54 nucleoporin complex. Science 350 (6256):106–110. doi: 10.1126/science.aac7420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Denning DP, Patel SS, Uversky V, Fink AL, Rexach M (2003) Disorder in the nuclear pore complex: the FG repeat regions of nucleoporins are natively unfolded. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100 (5):2450–2455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437902100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Timney BL, Raveh B, Mironska R, Trivedi JM, Kim SJ, Russel D, Wente SR, Sali A, Rout MP (2016) Simple rules for passive diffusion through the nuclear pore complex. J Cell Biol 215 (1):57–76. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201601004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Krull S, Thyberg J, Bjorkroth B, Rackwitz HR, Cordes VC (2004) Nucleoporins as components of the nuclear pore complex core structure and Tpr as the architectural element of the nuclear basket. Mol Biol Cell 15 (9):4261–4277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.McCloskey A, Ibarra A, Hetzer MW (2018) Tpr regulates the total number of nuclear pore complexes per cell nucleus. Genes Dev 32 (19–20):1321–1331. doi: 10.1101/gad.315523.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hase ME, Cordes VC (2003) Direct interaction with nup153 mediates binding of Tpr to the periphery of the nuclear pore complex. Mol Biol Cell 14 (5):1923–1940. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-09-0620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rajanala K, Nandicoori VK (2012) Localization of nucleoporin Tpr to the nuclear pore complex is essential for Tpr mediated regulation of the export of unspliced RNA. PLoS One 7 (1):e29921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rajanala K, Sarkar A, Jhingan GD, Priyadarshini R, Jalan M, Sengupta S, Nandicoori VK (2014) Phosphorylation of nucleoporin Tpr governs its differential localization and is required for its mitotic function. J Cell Sci 127 (Pt 16):3505–3520. doi: 10.1242/jcs.149112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Coyle JH, Bor YC, Rekosh D, Hammarskjold ML (2011) The Tpr protein regulates export of mRNAs with retained introns that traffic through the Nxf1 pathway. RNA 17 (7):1344–1356. doi: 10.1261/rna.2616111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Makise M, Mackay DR, Elgort S, Shankaran SS, Adam SA, Ullman KS (2012) The Nup153-Nup50 protein interface and its role in nuclear import. J Biol Chem 287 (46):38515–38522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.378893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Napetschnig J, Blobel G, Hoelz A (2007) Crystal structure of the N-terminal domain of the human protooncogene Nup214/CAN. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104 (6):1783–1788. doi:0610828104 [pii] 10.1073/pnas.0610828104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fontoura BM, Blobel G, Matunis MJ (1999) A conserved biogenesis pathway for nucleoporins: proteolytic processing of a 186-kilodalton precursor generates Nup98 and the novel nucleoporin, Nup96. J Cell Biol 144 (6):1097–1112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fontoura BM, Blobel G, Yaseen NR (2000) The nucleoporin Nup98 is a site for GDP/GTP exchange on ran and termination of karyopherin beta 2-mediated nuclear import. J Biol Chem 275 (40):31289–31296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004651200004651200 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Fontoura BM, Dales S, Blobel G, Zhong H (2001) The nucleoporin Nup98 associates with the intranuclear filamentous protein network of TPR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98 (6):3208–3213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.06101469898/6/3208 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Tamura K, Fukao Y, Iwamoto M, Haraguchi T, Hara-Nishimura I (2010) Identification and characterization of nuclear pore complex components in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 22 (12):4084–4097. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.079947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chakraborty P, Wang Y, Wei JH, van Deursen J, Yu H, Malureanu L, Dasso M, Forbes DJ, Levy DE, Seemann J, Fontoura BM (2008) Nucleoporin levels regulate cell cycle progression and phase-specific gene expression. Dev Cell 15 (5):657–667. doi:S1534–5807(08)00344–4 [pii] 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.08.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chakraborty P, Seemann J, Mishra RK, Wei JH, Weil L, Nussenzveig DR, Heiber J, Barber GN, Dasso M, Fontoura BM (2009) Vesicular stomatitis virus inhibits mitotic progression and triggers cell death. EMBO Rep 10 (10):1154–1160. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Liang Y, Franks TM, Marchetto MC, Gage FH, Hetzer MW (2013) Dynamic association of NUP98 with the human genome. PLoS Genet 9 (2):e1003308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Mor A, White MA, Fontoura BM (2014) Nuclear trafficking in health and disease. Curr Opin Cell Biol 28:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Franks TM, McCloskey A, Shokirev MN, Benner C, Rathore A, Hetzer MW (2017) Nup98 recruits the Wdr82-Set1A/COMPASS complex to promoters to regulate H3K4 trimethylation in hematopoietic progenitor cells. Genes Dev 31 (22):2222–2234. doi: 10.1101/gad.306753.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Rosenblum JS, Blobel G (1999) Autoproteolysis in nucleoporin biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96 (20):11370–11375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kalverda B, Pickersgill H, Shloma VV, Fornerod M (2010) Nucleoporins directly stimulate expression of developmental and cell-cycle genes inside the nucleoplasm. Cell 140 (3):360–371. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Capelson M, Liang Y, Schulte R, Mair W, Wagner U, Hetzer MW (2010) Chromatin-bound nuclear pore components regulate gene expression in higher eukaryotes. Cell 140 (3):372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Laurell E, Beck K, Krupina K, Theerthagiri G, Bodenmiller B, Horvath P, Aebersold R, Antonin W, Kutay U (2011) Phosphorylation of Nup98 by multiple kinases is crucial for NPC disassembly during mitotic entry. Cell 144 (4):539–550. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Laurell E, Kutay U (2011) Dismantling the NPC permeability barrier at the onset of mitosis. Cell Cycle 10 (14). doi:16195 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Stuwe T, von Borzyskowski LS, Davenport AM, Hoelz A (2012) Molecular basis for the anchoring of proto-oncoprotein Nup98 to the cytoplasmic face of the nuclear pore complex. J Mol Biol 419 (5):330–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.03.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Enninga J, Levy DE, Blobel G, Fontoura BM (2002) Role of nucleoporin induction in releasing an mRNA nuclear export block. Science 295 (5559):1523–1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Champion L, Linder MI, Kutay U (2017) Cellular Reorganization during Mitotic Entry. Trends Cell Biol 27 (1):26–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Linder MI, Kohler M, Boersema P, Weberruss M, Wandke C, Marino J, Ashiono C, Picotti P, Antonin W, Kutay U (2017) Mitotic Disassembly of Nuclear Pore Complexes Involves CDK1- and PLK1-Mediated Phosphorylation of Key Interconnecting Nucleoporins. Dev Cell 43 (2):141–156 e147. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.08.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Blethrow JD, Glavy JS, Morgan DO, Shokat KM (2008) Covalent capture of kinase-specific phosphopeptides reveals Cdk1-cyclin B substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105 (5):1442–1447. doi:0708966105 [pii] 10.1073/pnas.0708966105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.De Souza CP, Osmani SA (2007) Mitosis, not just open or closed. Eukaryot Cell 6 (9):1521–1527. doi:EC.00178–07 [pii] 10.1128/EC.00178-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.De Souza CP, Horn KP, Masker K, Osmani SA (2003) The SONB(NUP98) nucleoporin interacts with the NIMA kinase in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 165 (3):1071–1081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.De Souza CP, Hashmi SB, Horn KP, Osmani SA (2006) A point mutation in the Aspergillus nidulans sonBNup98 nuclear pore complex gene causes conditional DNA damage sensitivity. Genetics 174 (4):1881–1893. doi:genetics.106.063438 [pii] 10.1534/genetics.106.063438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Jeganathan KB, Malureanu L, van Deursen JM (2005) The Rae1-Nup98 complex prevents aneuploidy by inhibiting securin degradation. Nature 438 (7070):1036–1039. doi:nature04221 [pii] 10.1038/nature04221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.von Kobbe C, van Deursen JM, Rodrigues JP, Sitterlin D, Bachi A, Wu X, Wilm M, Carmo-Fonseca M, Izaurralde E (2000) Vesicular stomatitis virus matrix protein inhibits host cell gene expression by targeting the nucleoporin Nup98. Mol Cell 6 (5):1243–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Panda D, Pascual-Garcia P, Dunagin M, Tudor M, Hopkins KC, Xu J, Gold B, Raj A, Capelson M, Cherry S (2014) Nup98 promotes antiviral gene expression to restrict RNA viral infection in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111 (37):E3890–3899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410087111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Singer S, Zhao R, Barsotti AM, Ouwehand A, Fazollahi M, Coutavas E, Breuhahn K, Neumann O, Longerich T, Pusterla T, Powers MA, Giles KM, Leedman PJ, Hess J, Grunwald D, Bussemaker HJ, Singer RH, Schirmacher P, Prives C (2012) Nuclear pore component Nup98 is a potential tumor suppressor and regulates posttranscriptional expression of select p53 target genes. Mol Cell 48 (5):799–810. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Faria AM, Levay A, Wang Y, Kamphorst AO, Rosa ML, Nussenzveig DR, Balkan W, Chook YM, Levy DE, Fontoura BM (2006) The nucleoporin Nup96 is required for proper expression of interferon-regulated proteins and functions. Immunity 24 (3):295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Gough SM, Slape CI, Aplan PD (2011) NUP98 gene fusions and hematopoietic malignancies: common themes and new biologic insights. Blood 118 (24):6247–6257. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-328880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Cohen M, Feinstein N, Wilson KL, Gruenbaum Y (2003) Nuclear pore protein gp210 is essential for viability in HeLa cells and Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Biol Cell 14 (10):4230–4237. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e03-04-0260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kupke T, Malsam J, Schiebel E (2017) A ternary membrane protein complex anchors the spindle pole body in the nuclear envelope in budding yeast. J Biol Chem 292 (20):8447–8458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.780601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Mansfeld J, Guttinger S, Hawryluk-Gara LA, Pante N, Mall M, Galy V, Haselmann U, Muhlhausser P, Wozniak RW, Mattaj IW, Kutay U, Antonin W (2006) The conserved transmembrane nucleoporin NDC1 is required for nuclear pore complex assembly in vertebrate cells. Mol Cell 22 (1):93–103. doi:S1097–2765(06)00117–1 [pii] 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Antonin W, Mattaj IW (2005) Nuclear pore complexes: round the bend? Nat Cell Biol 7 (1):10–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Stavru F, Hulsmann BB, Spang A, Hartmann E, Cordes VC, Gorlich D (2006) NDC1: a crucial membrane-integral nucleoporin of metazoan nuclear pore complexes. J Cell Biol 173 (4):509–519. doi:jcb.200601001 [pii] 10.1083/jcb.200601001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Onischenko E, Stanton LH, Madrid AS, Kieselbach T, Weis K (2009) Role of the Ndc1 interaction network in yeast nuclear pore complex assembly and maintenance. J Cell Biol 185 (3):475–491. doi:jcb.200810030 [pii] 10.1083/jcb.200810030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Chadrin A, Hess B, San Roman M, Gatti X, Lombard B, Loew D, Barral Y, Palancade B, Doye V (2010) Pom33, a novel transmembrane nucleoporin required for proper nuclear pore complex distribution. J Cell Biol 189 (5):795–811. doi:jcb.200910043 [pii] 10.1083/jcb.200910043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Floch AG, Tareste D, Fuchs PF, Chadrin A, Naciri I, Leger T, Schlenstedt G, Palancade B, Doye V (2015) Nuclear pore targeting of the yeast Pom33 nucleoporin depends on karyopherin and lipid binding. J Cell Sci 128 (2):305–316. doi: 10.1242/jcs.158915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Weis K (2002) Nucleocytoplasmic transport: cargo trafficking across the border. Curr Opin Cell Biol 14 (3):328–335. doi:S095506740200337X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Bonner WM (1975) Protein migration into nuclei. II. Frog oocyte nuclei accumulate a class of microinjected oocyte nuclear proteins and exclude a class of microinjected oocyte cytoplasmic proteins. J Cell Biol 64 (2):431–437. doi: 10.1083/jcb.64.2.431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Bonner WM (1975) Protein migration into nuclei. I. Frog oocyte nuclei in vivo accumulate microinjected histones, allow entry to small proteins, and exclude large proteins. J Cell Biol 64 (2):421–430. doi: 10.1083/jcb.64.2.421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Stewart M (2007) Molecular mechanism of the nuclear protein import cycle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8 (3):195–208. doi:nrm2114 [pii] 10.1038/nrm2114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Lange A, Mills RE, Lange CJ, Stewart M, Devine SE, Corbett AH (2007) Classical nuclear localization signals: definition, function, and interaction with importin alpha. J Biol Chem 282 (8):5101–5105. doi:R600026200 [pii] 10.1074/jbc.R600026200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Mosalaganti S, Kosinski J, Albert S, Schaffer M, Strenkert D, Salome PA, Merchant SS, Plitzko JM, Baumeister W, Engel BD, Beck M (2018) In situ architecture of the algal nuclear pore complex. Nat Commun 9. doi:ARTN 2361 10.1038/s41467-018-04739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]