Introduction

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is one of the most common and important diseases worldwide.1 The prevalence of dyspepsia in Thailand is 66%, and 60-90% of these patients exhibit FD.2 Although, FD is a benign disease, it significantly decreases the quality of life.3,4

Most guidelines recommend an empirical trial of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for 4-8 weeks as first-line treatment.5-7 However, the overall response rate of FD patients to PPI treatment varies between 30-50%, and only 10-20% achieve a therapeutic gain over placebo.8-12 Approximately half of FD patients do not respond well to PPI treatment.

The management of PPI non-responsive FD is a challenge. Several pathophysiological mechanisms were proposed, and the treatment options directly target the underlying processes.13,14 Tricyclic antidepressants modify visceral hypersensitivity and brain-gut interactions and prokinetics, which regulate gut motility, and the use of these agents is proposed in clinical guidelines.5,6 However, some of the treatment options have limited evidence to support their use, including antispasmodics, analgesics, and over-the-counter remedies.15

Clidinium bromide is an anticholinergic/antispasmodic agent, and chlordiazepoxide hydrochloride is a benzodiazepine/anxiolytic drug. The United States Food and Drug Administration approved the use of this combination, clidinium/chlordiazepoxide, as an adjunct therapy for the treatment of peptic ulcer, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and acute enterocolitis. Based on pathophysiological abnormalities in FD, clidinium/chlordiazepoxide may act on the gastroduodenal motor and psychosocial disturbance16-18 to potentially benefit FD patients. However, to date, there are no adequate trials to support their efficacy. Therefore, we assessed the efficacy and safety of clidinium/chlordiazepoxide as an add-on to PPI therapy in refractory FD.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This study was a prospective, single-center, double-blind, randomized control, placebo-controlled trial study conducted at our hospital from March 2017 through February 2018. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All patients provided written informed consent to participate in the study. This trial is registered with the Thai Clinical Trials Registry (No. TCTR20171016004).

Participants

Eligible patients, aged 18 years to 70 years, who were diagnosed with FD according to Rome IV criteria,19 were invited to participate in this study. All patients had normal upper endoscopy and no evidence of Helicobacter pylori infection within 1 year before enrolment. FD subtypes were determined from a structured interview during the baseline visit. All patients remained symptomatic after treatment with a standard dose of PPI for 8 weeks prior to enrolment.

Exclusion criteria included predominant symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or IBS; a history of using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelets or anticoagulants within 1 month before enrolment; severe comorbid diseases; a history of psychological distress, mental health problems, uncontrolled glaucoma, or obstructive uropathy; and current or planned pregnancy.

Randomisation and Intervention

Randomisation was done using computer-generated blocking randomization. Patients were randomized into 1 of 2 study arms. An independent staff member assigned the treatments according to consecutive numbers, which were kept in sealed envelopes. All investigators and patients were blinded to treatment allocation.

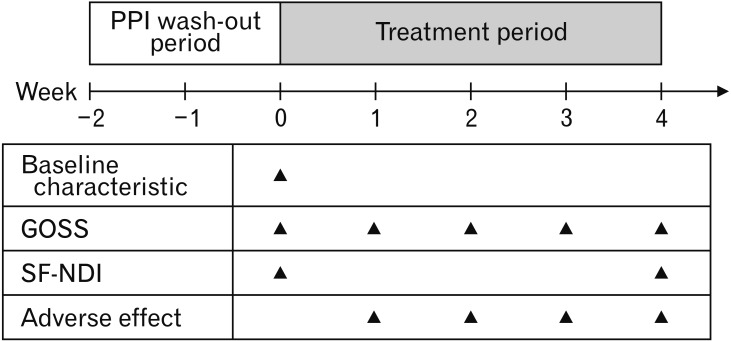

Eligible patients had a 2-week PPI wash-out and baseline assessment period before randomisation. Patients received clidinium/chlordiazepoxide or placebo 3 times daily together with a standard dose of omeprazole once daily for 4 weeks. Patients in the treatment arm were given a capsule containing 2.5 mg of clidinium bromide and 5 mg of chlordiazepoxide hydrochloride (Tumax; Sriprasit Pharma Co, Ltd, Samut Skhon, Thailand), and patients in the placebo arm were given an identical capsule containing starch as the add-on therapy to omeprazole. Patients were advised to avoid the use of over-the-counter medications during the study. Compliance was checked via interview and pill count.

Outcome Assessment

Baseline characteristics (age, sex, body mass index, smoking, alcohol drinking, underlying medical disease, FD subtype, and symptom duration) were recorded.

Symptom severity was evaluated by a global overall symptom scale (GOSS, using a 7-point Likert dyspepsia severity scale).20 The scores of each symptom were summed and resulted in a total score of 8 to 56. The GOSS was assessed at baseline and weekly until completion of the 4 weeks of study. Patients who exhibited decreased GOSS > 50% from baseline were considered responders.

The short form Nepean dyspepsia index (SF-NDI) was used to assess FD quality of life at baseline and week 4 of treatment. NDI scores were summarized into overall quality of life and 5 subscales (Interference, Knowledge/Control, Eating/Drinking, Sleep Disturbance, and Work/Study), which resulted in a total score of 10 to 50. Higher scores of GOSS and NDI indicated more severe symptoms and a lower quality of life.21 The timeline of the study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study design. PPI, proton pump inhibitor; GOSS, global overall symptom scale; SF-NDI, short form Nepean dyspepsia index.

The primary outcome was the percentage of responders. The secondary outcomes were improvement in the quality of life at 4 weeks and the safety profile.

Statistical Methods

To date, the placebo response in FD is approximately 30% to 40% among patients in randomized-controlled trials.22 In 1961, Holloman23 reported the clinical experience of 106 patients using clidinium/chlordiazepoxide for upper gastrointestinal diseases, primarily peptic ulcer disease, and ulcer-like dyspepsia, and showed that 85% of patients had marked symptom improvement. Since the sample size calculations were based on the estimation that the proportions of responders would be 30% in the placebo group and 70% in the treatment group, and the additive effect would expect to be 40%, with a 5% β-error and a 20% β-error. Taking a 20% drop-out rate into account, the number of participants in this study was 30 patients in each arm. The primary outcomes were based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis. For the primary outcome, the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used to analyse the difference between the 2 treatment groups using the proportion of responders and the dyspepsia symptom score. For the secondary outcomes, quality of life scores was compared between the 2 treatment groups using unpaired t test or Mann-Whitney U test. For the safety assessment, the incidences of adverse events were compared using the chi-square test. Analyses were performed in SPSS version 18 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Enrollment and Baseline Characteristics

Between March 2017 and February 2018, 78 patients were enrolled and randomly assigned to the clidinium/chlordiazepoxide group (n = 39) or placebo group (n = 39). The patients’ baseline clinical and laboratory characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between treatment and placebo groups in baseline characteristics, including age, sex, body mass index, underlying diseases, smoking, and alcohol status, duration of symptoms, dyspepsia subtypes, and disease severity score. However, the quality of life in the treatment group was worse than that in the placebo group. Two patients (5%) in the treatment group and 3 patients (8%) in the placebo group were lost to follow up. Therefore, 73 patients completed the study (37 with treatment and 36 with placebo, shown in Figure 2. The overall compliance with the study medications was greater than 90% for all participants.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristics | Clidinium/Chlordiazepoxide (n = 39) | Placebo (n = 39) | P-values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 43 (36.5-60.5) | 50 (39-59) | 0.204 |

| Female | 25 (75.8) | 21 (67.7) | 0.664 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.3 (19.6-24.5) | 22.6 (20.4-25.2) | 0.188 |

| Underlying disease | 15 (45.5) | 11 (35.5) | 0.578 |

| Hypertension | 8 (53.3) | 6 (54.5) | 0.865 |

| Other | 7 (46.7) | 5 (45.5) | |

| Smoker | 1 (3.0) | 3 (9.7) | 0.347 |

| Alcohol drinker | 4 (12.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.114 |

| Duration of symptom (months) | 16 (10-24) | 12 (12-36) | 0.608 |

| FD Subtype | 0.399 | ||

| PDS | 9 (27.3) | 12 (38.7) | |

| EPS | 11 (33.3) | 6 (19.4) | |

| Mixed type | 13 (39.4) | 13 (41.9) | |

| GOSS | 32.6 ± 7.2 | 31.2 ± 8.1 | 0.427 |

| Short form NPI | 30.1 ± 5.9 | 26.8 ± 6.6 | 0.026 |

BMI, body mass index; FD, functional dyspepsia; PDS, postprandial distress syndrome; EPS, epigastrium pain syndrome; GOSS, global overall symptom scale; NPI, Nepean dyspepsia index.

Data are presented as median (interquartile range), number (%), or mean ± SD.

Figure 2.

Study flow chart.

Dyspepsia Symptom Score

In the ITT analysis, the rates of responders in the treatment and placebo groups were 7.69% and 0.00% at week 1 (P = 0.077), 25.64% and 5.13% at week 2 (P = 0.012), 28.21% and 5.13% at week 3 (P = 0.006), and 41.03% and 5.13% at week 4 (P < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 3). The treatment group had a therapeutic gain of 35.73% over the placebo group. Per-protocol analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1) did not substantially change as compared to ITT analysis. Comparison of the mean difference in GOSS pre- and post-treatment within each group revealed a significant decrease in overall and symptom-specific score in the clidinium/chlordiazepoxide group compared to the placebo group (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Rate of responders between groups by intention to treat analysis.

Table 2.

The Mean Difference in Severity Score (Global Overall Symptom Scale) Between Groups

| Symptom | Clidinium/chlordiazepoxide (n = 37) | Placebo (n = 36) | P-values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (mean ± SD) | Week 4 (mean ± SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | Baseline (mean ± SD) | Week 4 (mean ± SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | ||

| Overall symptoms | 32.30 ± 7.22 | 16.51 ± 5.58 | –15.78 (–18.24, –13.33) | 31.53 ± 7.64 | 26.75 ± 10.50 | –4.78 (–7.43, –2.13) | < 0.001 |

| Epigastric pain | 4.89 ± 1.52 | 2.51 ± 1.17 | –2.38 (–2.83, –1.93) | 5.00 ± 1.55 | 4.14 ± 1.84 | –0.86 (–1.34, –0.38) | < 0.001 |

| Epigastric burning | 4.62 ± 1.74 | 2.08 ± 0.95 | –2.54 (–3.10, –1.98) | 3.72 ± 2.08 | 3.33 ± 2.19 | –0.39 (–0.78, 0.00) | < 0.001 |

| Heartburn or regurgitation | 4.76 ± 1.79 | 2.32 ± 1.16 | –2.43 (–3.02, –1.85) | 4.91 ± 1.36 | 3.89 ± 1.85 | –1.03 (–1.58, –0.48) | 0.001 |

| Early satiety | 3.27 ± 1.97 | 1.76 ± 1.12 | –1.51 (–2.07, –0.96) | 3.36 ± 1.93 | 2.83 ± 1.70 | –0.53 (–0.94, –0.11) | 0.005 |

| Nausea | 2.57 ± 1.90 | 1.38 ± 0.79 | –1.19 (–1.73, –0.65) | 2.56 ± 1.71 | 2.22 ± 1.62 | –0.33 (–0.67, 0.00) | 0.008 |

| Belching | 4.32 ± 1.75 | 2.57 ± 1.39 | –1.76 (–2.28, –1.23) | 4.78 ± 1.49 | 4.03 ± 1.63 | –0.75 (–1.16, –0.34) | 0.003 |

| Postprandial fullness | 4.30 ± 1.76 | 2.16 ± 1.26 | –2.14 (–2.65, –1.62) | 4.08 ± 1.70 | 3.64 ± 1.71 | –0.44 (–0.87, –0.02) | < 0.001 |

| Epigastric bloating | 3.57 ± 2.05 | 1.73 ± 0.99 | –1.84 (–2.41, –1.263) | 3.11 ± 2.14 | 2.67 ± 2.03 | –0.44 (–0.88, –0.01) | < 0.001 |

According to dyspepsia subtype (Supplementary Fig. 2), the responder rate at week 4 in postprandial distress syndrome (PDS) subtype (n = 21) was 33.33% (treatment group) and 0.0% (placebo group) (P = 0.025), in epigastrium pain syndrome (EPS) subtype (n = 17) was 28.57% (treatment group) and 16.67% (placebo group) (P = 0.573), in mixed subtype (n = 26) was 64.29% (treatment group) and 5.88% (placebo group) (P = 0.001).

Quality of Life

Evaluation using the SF-NDI index demonstrated that at baseline the treatment group was significantly higher than the placebo group (30.1 ± 5.9 vs 26.8 ± 6.6, P = 0.026). This means the treatment group has a poorer quality of life compared to the placebo group, this may occur from small sample size and potential cause bias for the study. Nevertheless, SF-NDI is not affected in the primary outcome analysis and the change of overall SF-NDI at week 4 of the study was significantly different between the treatment group –14.35 (–16.48, –12.23) and placebo group –3.44 (–5.77, –1.11) (Table 3).

Table 3.

The Mean Difference in the Quality of Life Scale (Short Form Nepean Dyspepsia Index) Between Groups

| Parameter | Clidinium/chlordiazepoxide (n = 37) | Placebo (n = 36) | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (mean ± SD) | Week 4 (mean ± SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | Baseline (mean ± SD) | Week 4 (mean ± SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | ||

| Overall | 30.38 ± 6.15 | 16.03 ± 4.86 | –14.35 (–16.48, –12.23) | 27.75 ± 7.24 | 24.31 ± 8.59 | –3.44 (–5.77, –1.11) | < 0.001 |

| Tension | 7.38 ± 1.69 | 3.76 ± 1.16 | –3.62 (–4.30, –2.94) | 6.58 ± 1.30 | 5.50 ± 1.80 | –1.08 (–1.71, –0.46) | < 0.001 |

| Interference with daily activities | 4.89 ± 2.71 | 2.73 ± 1.37 | –2.16 (–2.99, –1.34) | 4.44 ± 2.80 | 4.14 ± 2.44 | –0.31 (–0.92, 0.30) | 0.001 |

| Eating/drinking | 4.76 ± 1.86 | 3.14 ± 1.18 | –1.62 (–2.23, –1.02) | 5.08 ± 2.10 | 4.83 ± 1.96 | –0.25 (–0.91, 0.41) | 0.003 |

| Knowledge/control | 7.89 ± 1.54 | 3.62 ± 1.25 | –4.27 (–4.92, –3.62) | 7.31 ± 1.85 | 5.64 ± 2.03 | –1.67 (–2.38, –0.95) | < 0.001 |

| Work/study | 5.46 ± 2.86 | 2.78 ± 1.27 | –2.68 (–3.58, –1.77) | 4.33 ± 2.61 | 4.19 ± 2.55 | –0.14 (–0.76, 0.48) | < 0.001 |

Safety and Tolerability

There were 24 adverse events reported (Fig. 4). The most frequently reported adverse event was drowsiness/somnolence. The treatment group had more frequent drowsiness than the placebo group (30.27% and 6.52%, respectively, P = 0.034). However, no patient dropped out due to adverse events. No serious adverse events were reported during the 4 weeks of study.

Figure 4.

Rates of adverse events.

Discussion

The pathogenesis of FD is an expected heterogeneous condition. Most of the standard treatment usually focuses on gastric abnormality, typically PPIs and prokinetics, however, the overall results are still inadequate. Recent researches supported that subtle inflammation in the duodenum may be involved in the pathophysiology of FD, followed by sensory-motor dysfunction.24 According to this data, anxiolytics combined with antispasmodics may be a potential new therapeutic option in FD. We noticed that the anti-spasmodic drug can use to treat FD well in our clinic, particularly when it combined with neuromodulator such as clidinium/chlordiazepoxide. In 1961, Holloman23 reported the clinical experience of 106 patients using clidinium/chlordiazepoxide for upper gastrointestinal diseases, primarily peptic ulcer disease and ulcer-like dyspepsia, and showed that 85% of patients had marked symptom improvement without evidence of adverse events. However, this study only reported a clinical experience without placebo control.

Our randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial showed the effectiveness of clidinium/chlordiazepoxide as an add-on to PPI for the treatment of refractory FD patients with a therapeutic gain of approximately 36% over placebo and improved quality of life, as indicated in the significant decrease of SF-NDI scores from baseline (–14.35) at week 4 compared to placebo with PPI (–3.44). The response rate in the treatment group compared to the placebo group tended to increase over time (7.69% vs 0.00% at week 1, 25.64% vs 5.13% at week 2, 28.21% vs 5.13% at week 3, and 41.03% vs 5.13% at week 4, respectively) with a significant superiority of treatment over placebo from the second week of treatment. However, the response rate of the placebo group in our study (5.13%) was lower than previous studies (around 30-40%),25 which may be because the patients enrolled in our trial were truly PPI-nonresponsive patients at a tertiary care center.

Clidinium/chlordiazepoxide add-on to PPI improved almost all symptom subtypes, including epigastrium pain, epigastrium burning, early satiety, postprandial fullness, belching and bloating, and only nausea did not improve. This result indirectly suggests that clidinium/chlordiazepoxide may be used for EPS and PDS in FD patients. However, in subgroup analysis for FD subtype, clidinium/chlordiazepoxide add-on was effective in PDS subtype (33.33% vs 0.0%, P = 0.025) and mixed subtype (64.29% vs 5.88%, P = 0.001), but not for EPS subtype (28.57% vs 16.67%, P = 0.573). In our opinion, the response rate of placebo group (PPI alone) in the EPS subtype was higher than PDS and mixed subtype; these made the therapeutic gain in EPS subtype lower, together with a lower number of patients in EPS subtype (n = 17), these may cause insufficient power to interpret this result.

Clidinium bromide is an anticholinergic (specifically a muscarinic antagonist) drug as opposed to the acotiamide which is known to effective in FD.26 The anticholinergic effect can decrease gastric contraction and accommodation that may worsen the symptom of FD.27 However, our study showed that clidinium/chlordiazepoxide is effective in PDS and mixed subtype. We do not understand the exact mechanism behind this result; in our opinion, we think this may be related to small bowel dysmotility. Several studies, using manometry in FD patients, suggested abnormal motility is not only confined to the stomach; proximal small intestinal also showed a high prevalence of dysmotility.28,29 The recent study using 24-hour antrojejunal ambulatory manometry in severe motility-like dyspepsia showed small bowel dysmotility postprandial period; also the most frequent qualitative abnormalities pattern has been observed in previous IBS studies.29,30 We hypothesis that antispasmodic may modulate abnormal small bowel contractility; possibly the same effect that antispasmodic showed effectiveness in IBS treatment. Nevertheless, we did not perform manometry to prove our hypothesis.

The adverse events in our study were similar in the treatment and placebo groups, except for drowsiness, which was significantly more common in the clidinium/chlordiazepoxide group (30%) than in the placebo group (7%). However, most of the patients reported only mild drowsiness, and they maintained normal daily activity. No patient withdrew from our study due to drowsiness. The dropout rate was not significantly different between the treatment group (5%) and the placebo group (8%).

The strengths of our study include that it is the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to support the benefit of a combination of a low dose of an antispasmodic agent with a benzodiazepine add-on to PPI in FD patients. Second, all patients in our study were truly FD diagnosed using the Rome IV criteria, and all patients had a normal endoscopic examination and no evidence of H. pylori infection. Third, our trial strictly excluded patients with IBS symptoms to avoid the benefit of the antispasmodic in IBS patients. Many studies support the benefit of antispasmodics in patients with IBS,31,32 and the incidence of FD and IBS overlap in Asia varies from 2% to 49%.33

Our study has several limitations. First, we did not perform a physiological study to demonstrate the effect of the antispasmodic on gastric emptying time, gastric accommodation or small intestine motility. Second, the standard mental health screening tool was not used to exclude psychiatric diseases. Therefore, we cannot conclude that the results of our study were produced exclusively from the synergistic response to both drugs or occurred primarily because of the antispasmodic or anxiolytic drug. Third, this trial evaluated only 4 weeks of treatment instead of the typical 8-12 weeks used in other trials, because of concerns about the addictive potential of chlordiazepoxide and lack of extended follow-up period after treatment to assess the long-term efficacy and adverse effects of treatment.

In conclusion, this prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial showed that clidinium/chlordiazepoxide significantly improved dyspeptic symptoms and quality of life. It may be used as an add-on therapy in FD patients who failed to respond to PPI without any major adverse event. However, we recommend the use of clidinium/chlordiazepoxide as an adjunctive treatment for only a short duration to avoid the addiction potential.

Footnotes

Supplementary Materials

Note: To access the supplementary figures mentioned in this article, visit the online version of Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility at http://www.jnmjournal.org/, and at https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm19186.

Financial support: This study was supported by the Gastroenterological Association of Thailand. Sriprasit Pharma Co, Ltd, Thailand only provided clidinium/chlordiazepoxide and placebo, and it was not involved in the study design, data collection or interpretation, writing the report or the decision to submit the results.

Conflicts of interest: None.

Author contributions: Siripa Puasripun and Nithi Thinrungroj performed the research, collected, and analysed the data; Nithi Thinrungroj designed the research study and guarantor of the article; Siripa Puasripun and Nithi Thinrungroj wrote the paper; Kanokwan Pinyopornpanish, Phuripong Kijdamrongthum, Apinya Leerapun, and Taned Chitapanarux contributed to the design of the study; and Satawat Thongsawat and Ong-Ard Praisontarangkul helped revise the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript, including the authorship list.

References

- 1.Ford AC, Marwaha A, Sood R, Moayyedi P. Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, uninvestigated dyspepsia: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2015;64:1049–1057. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kachintorn U. Epidemiology, approach and management of functional dyspepsia in Thailand. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(suppl 3):32–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahadeva S, Yadav H, Rampal S, Everett SM, Goh KL. Ethnic variation, epidemiological factors and quality of life impairment associated with dyspepsia in urban Malaysia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:1141–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahadeva S, Yadav H, Rampal S, Goh KL. Risk factors associated with dyspepsia in a rural Asian population and its impact on quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:904–912. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talley NJ, Ford AC. Functional dyspepsia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1853–1863. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1501505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moayyedi P, Lacy BE, Andrews CN, Enns RA, Howden CW, Vakil N. ACG and CAG clinical guideline: management of dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:988–1013. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miwa H, Kusano M, Arisawa T, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for functional dyspepsia. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:125–139. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-1022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Talley NJ, Lauritsen K. The potential role of acid suppression in functional dyspepsia: the BOND, OPERA, PILOT, and ENCORE studies. Gut. 2002;50(suppl 4):iv36–iv41. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.suppl_4.iv36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Rensburg C, Berghöfer P, Enns R, et al. Efficacy and safety of pantoprazole 20 mg once daily treatment in patients with ulcer-like functional dyspepsia. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:2009–2018. doi: 10.1185/03007990802184545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Zanten SV, Armstrong D, Chiba N, et al. Esomeprazole 40 mg once a day in patients with functional dyspepsia: the randomized, placebo-controlled “ENTER” trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2096–2106. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki H, Kusunoki H, Kamiya T, et al. Effect of lansoprazole on the epigastric symptoms of functional dyspepsia (ELF study): a multicentre, prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. United European Gastroenterol J. 2013;1:445–452. doi: 10.1177/2050640613510904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwakiri R. Commentary: rabeprazole improves symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia in Japan - author’s reply. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:1322–1323. doi: 10.1111/apt.12512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stanghellini V, Chan FK, Hasler WL, et al. Gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1380–1392. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drossman DA. Functional gastrointestinal disorders: history, pathophysiology, clinical features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1262–1279.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brun R, Kuo B. Functional dyspepsia. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2010;3:145–164. doi: 10.1177/1756283X10362639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Talley NJ, Stanghellini V, Heading RC, Koch KL, Malagelada JR, Tytgat GN. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gut. 1999;45(suppl 2):II37–II42. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talley NJ, Silverstein MD, Agréus L, Nyrén O, Sonnenberg A, Holtmann G. AGA technical review: evaluation of dyspepsia. American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:582–595. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70542-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamawaki H, Futagami S, Shimpuku M, et al. Impact of sleep disorders, quality of life and gastric emptying in distinct subtypes of functional dyspepsia in Japan. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2014;20:104–112. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2014.20.1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stanghellini V, Chan FK, Hasler WL, et al. Gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1380–1392. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Chiba N, Armstrong D, et al. Validation of a 7-point global overall symptom scale to measure the severity of dyspepsia symptoms in clinical trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:521–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Talley NJ, Verlinden M, Jones M. Quality of life in functional dyspepsia: responsiveness of the Nepean Dyspepsia Index and development of a new 10-item short form. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:207–216. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Talley NJ, Locke GR, Lahr BD, et al. Predictors of the placebo response in functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:923–936. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holloman JL Jr. Librax in gastrointestinal disorders. J Natl Med Assoc. 1961;53:504–507. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jung HK, Talley NJ. Role of the duodenum in the pathogenesis of functional dyspepsia: a paradigm shift. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;24:345–354. doi: 10.5056/jnm18060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moayyedi P, Delaney BC, Vakil N, Forman D, Talley NJ. The efficacy of proton pump inhibitors in nonulcer dyspepsia: a systematic review and economic analysis. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1329–1337. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsushita M, Masaoka T, Suzuki H. Emerging treatments in neurogastroenterology: acotiamade, a novel treatment option for functional dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:631–638. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim BJ, Kuo B. Gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia: a blurring distinction of pathophysiology and treatment. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;25:27–35. doi: 10.5056/jnm18162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bassotti G, Pelli MA, Morelli A. Duodenojejunal motor activity in patients with chronic dyspeptic symptoms. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1990;12:17–21. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199002000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jebbink HJ, vanBerge-Henegouwen GP, Akkermans LM, Smout AJ. Small intestinal motor abnormalities in patients with functional dyspepsia demonstrated by ambulatory manometry. Gut. 1996;38:694–700. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.5.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kellow JE, Gill RC, Wingate DL. Prolonged ambulant recordings of small bowel motility demonstrate abnormalities in the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1990;98(5 Pt 1):1208–1218. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90335-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruepert L, Quartero AO, de Wit NJ, van der Heijden GJ, Rubin G, Muris JW. Bulking agents, antispasmodics and antidepressants for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD003460. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003460.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chey WD, Kurlander J, Eswaran S. Irritable bowel syndrome: a clinical review. JAMA. 2015;313:949–958. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.0954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghoshal UC, Singh R, Chang FY, Hou X, Wong BC, Kachintorn U. Epidemiology of uninvestigated and functional dyspepsia in Asia: facts and fiction. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:235–244. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2011.17.3.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.