Abstract

Background

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) epidemiology has been largely studied using symptom-based case definitions, without assessment of objective sinus findings.

Objective

To describe radiologic sinus opacification and the prevalence of CRS, defined by the co-occurrence of symptoms and sinus opacification, in a general population-based sample.

Methods

We collected questionnaires and sinus CT scans from 646 participants selected from a source population of 200,769 primary care patients. Symptom status (CRSS) was based on guideline criteria and objective radiologic inflammation (CRSO) was based on the Lund-Mackay (L-M) score using multiple L-M thresholds for positivity. Participants with symptoms and radiologic inflammation were classified as CRSS+O. We performed negative binomial regression to assess factors associated with L-M score and logistic regression to evaluate factors associated with CRSS+O. Using weighted analysis, we calculated estimates for the source population.

Results

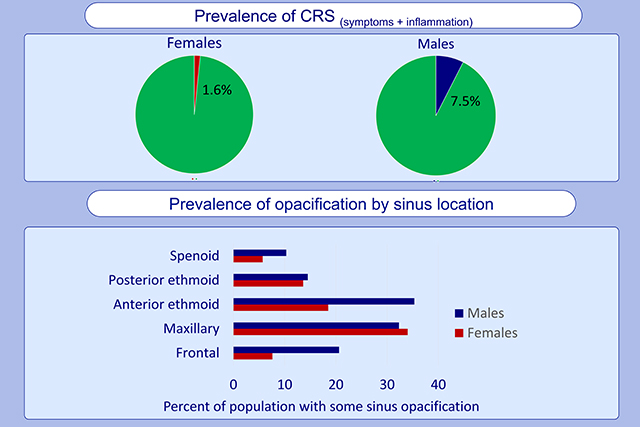

The proportion of women with L-M scores greater than or equal to three, four, or six (CRSO) was 11.1%, 9.9%, and 5.7%, respectively, and 16.1%, 14.6%, and 8.7% among men. The respective proportion with CRSS+O was 1.7%, 1.6%, and 0.45% among women and 8.8%, 7.5%, and 3.6% among men. Men had higher odds of CRSS+O compared to women. A greater proportion of men (vs. women) had any opacification in the frontal, anterior ethmoid, and sphenoid sinuses.

Conclusion

In a general population-based sample in Pennsylvania, sinus opacification was more common among men than in women and opacification occurred in different locations by sex. Male sex, migraine headache, and prior sinus surgery were associated with higher odds of CRSS+O.

Keywords: Chronic rhinosinusitis, CT scan, Epidemiology, Sex, Sinus

Graphical Abstract

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) has been referred to as “the unrecognized epidemic” because of reports of its high prevalence and burden, coupled with a limited understanding of its epidemiology.1 CRS is defined by the presence of nasal and sinus symptoms for at least three months, accompanied by sinus inflammation, documented by either sinus computed tomography (CT) scan or endoscopy.2,3 However, most of the knowledge of the epidemiology of CRS has been derived from studies that defined CRS based on symptoms alone, despite discordance between symptoms and CT evidence of disease.4,5 Such case definitions, while informative about sinus symptom epidemiology, may not accurately identify persons with sinus inflammation. This could potentially result in incorrect assumptions about the pathophysiology of CRS.

CRS epidemiologic studies generally depend on symptoms due to the logistical challenges of obtaining endoscopy or CTs. The Lund-Mackay (L-M) scoring system, the opacification staging system recommended by the Task Force on Rhinosinusitis,6 was developed for patients undergoing sinus surgery. Studies that have incorporated this measure have largely been confined to patients seeking care for sinus disease in tertiary care settings, representing the severe end of the disease spectrum.4,6,7,8 These studies tell us little about the full spectrum of CRS in the general population. In 2018, the GA2LEN study attempted to address this limitation in a study of CRS prevalence in Europe. This study was confined to patients in a non-rhinologic population undergoing CT for clinical indications other than sinus disease.9 Excluding patients undergoing sinus CT scans may have resulted in an underestimate of CRS prevalence and a patient population having a sinus CT scan may not be representative of the full spectrum of disease in the general population. No study to date has evaluated the prevalence of CRS, based on sinus CT and appropriate symptoms, in the general population.

We report on a cross-sectional study of nasal and sinus symptoms and sinus CT opacification among a general population sample. The goals of the analysis were to describe radiologic sinus inflammation patterns by sex; estimate the prevalence of CRS, defined by the co-occurrence of symptoms and sinus inflammation; and evaluate risk factors for these outcomes in a general population-representative sample in the U.S.

METHODS

Study population

We conducted sinus CT scans on 646 subjects from a previously-reported cohort,10 the 7847 baseline questionnaire respondents in the Chronic Rhinosinusitis Integrative Study Program’s (CRISP) study. Briefly, 23,700 individuals were selected from 200,769 Geisinger adult primary care patients to receive questionnaires regarding nasal and sinus symptoms. Stratified random sampling was used to over-sample those with sinus symptoms and racial/ethnic minorities to ensure adequate sample sizes. Geisinger is a health system serving more than 40 counties in Pennsylvania. Geisinger’s primary care population is representative of the general population in the region.11 This study was approved by Geisinger’s Institutional Review Board.

Participant selection and recruitment

Stratified random sampling was used to over-sample those with nasal and sinus symptoms based on previously completed questionnaires. We sent letters to eligible participants asking them to return a signed consent form if they were interested in participating. We scheduled a sinus CT examination with consented participants and mailed them a sinus symptom questionnaire to be returned prior to the CT visit. Individuals who were pregnant were excluded. CT visits were postponed for individuals reporting a cold or upper respiratory infection. Patients received a $60 gift card for participating. A total of 3269 subjects were invited to participate.

CT imaging and scoring

Non-contrast sinus CT scans (coronal 3 mm slices) were obtained with a low radiation dose research protocol approved by Geisinger’s Radiation Safety Committee. All CT images were de-identified and then independently read by two otorhinolaryngologists who were blinded to subject data, using a modified L-M protocol that scored each of five sinus locations (maxillary, anterior ethmoid, posterior ethmoid, sphenoid, frontal sinus) on the left and right side for degree of opacification on a scale of 0 to 4 (0 = 0% opacification, 1 = 1–33%, 2 = 34–66%, 3 = 67–99%, or 4 = 100%). Reviewers scored the osteomeatal complex from 0 to 2 (0 = not occluded, 1 = partially occluded, or 2 = occluded); and the degree of nasal cavity opacification from 0 to 4 (0 = none, 1 = above middle turbinate, 2 = above inferior turbinate, 3 = at or below inferior turbinate, or 4 = total opacification). When reviewer scores on a sinus location differed by two or more points, reviewers were asked to reconcile scores. Average scores were used when scores differed by one point. Finally, reviewers were asked to indicate if there was evidence on the CT images of prior sinus surgery. Reviewer scores were converted to the standard L-M scoring for sinuses (0 = no opacification, 1 = partial, or 2 = complete) and osteomeatal complex (0 = not occluded or 2 = occluded). Converted scores were then summed to generate a total L-M score,4 ranging from 0 to 24. Objective evidence of CRS (CRSO, o for objective) was evaluated using multiple thresholds for L-M score positivity.

Clinical and demographic characteristics

CRS symptom status (CRSS) was determined based on responses to a questionnaire sent at time of CT study recruitment. As previously reported,10 participants were categorized into one of three CRSS categories based on the European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis (EPOS) symptom criteria: “current” if participants met EPOS criteria at the time of the questionnaire, “past” if they reported EPOS symptoms in the past, and “never” if they did not meet EPOS criteria in their lifetime.10 Subjects were defined as meeting the CRS clinical criteria if they had both CRSS current and CRSO (CRSS+O).

Demographic data were obtained from electronic health records. Migraine headache, asthma, and anxiety sensitivity index (ASI) data were collected via CRISP questionnaires.12,13 Migraine headache status was based on the ID Migraine questionnaire12 and asthma was based on self-report of a doctor diagnosis. Anxiety sensitivity refers to the fear of anxiety-related physical sensations resulting from the belief that these sensations may have potentially harmful consequences.13,14 The ASI is a validated instrument with total scores ranging from 0 to 64; higher scores indicate higher anxiety sensitivity.14 We hypothesized that ASI scores could be used as an indicator of the propensity to overreport symptoms. Sinus surgery history (yes vs. no) was based on evidence of surgery on the sinus CT scan.

Statistical analysis

The goal of the analysis was to describe the prevalence of CRSO and CRSS+O in the general population in our study region and to evaluate associations between demographic and clinical factors with CRSS+O. We first estimated the prevalence of CRSO and CRSS+O in the source population, the original 200,769 primary care patients from whom participants were selected, using three different L-M thresholds for positivity (≥ 3, ≥ 4, ≥ 6). Analysis was weighted using native weights for sampling and participation by symptom status and race/ethnicity for the baseline questionnaire and CT portions of the study, enabling the calculation of these estimates for the source population (Online Repository).

We used chi-square tests to compare the proportion of individuals with CRSO by sex; race/ethnicity (white, non-white); age (years); migraine headache status (yes/no); CRSS (current, past, never); ASI score (below median vs. at or above median); self-reported physician-diagnosed asthma status (yes/no); and prior sinus surgery (yes/no). We then compared the proportions of subjects who had any opacification (L-M score > 0) by sinus location using chi-square tests by the previously described subject characteristics. Next, we determined the proportion of subjects with CRSS+O by these characteristics.

To assess what factors were associated with L-M score, we conducted negative binomial regression with integer L-M score as the outcome. We developed a model that included demographic (sex, age, race/ethnicity) characteristics and CRSS, parameterized as described above. We then added the following variables one at a time: migraine headache, asthma, surgery history, ASI, and smoking status from the electronic health record (current, past, never). Variables were retained if they were associated with L-M score. Next, we evaluated whether sex, migraine headache, or ASI score modified associations between CRSS and L-M score, by adding interaction terms to the previously described model. Finally, we used logistic regression to evaluate associations between this same set of covariates and CRSS+O status (yes/no).

For all models, we conducted analysis using unweighted, native weighting, and truncated weighting. For weighted analysis using native weights, we applied the weighting methods described above to balance bias with precision in association estimates; bias is reduced with weighted analysis but precision is also reduced.15,16 Using this weighting approach inflated standard errors, a known consequence of large sampling weights,15,16 so we truncated our native weights to a maximum relative weight of 30 times the smallest weight, a standard method for dealing with larger weights (Online Repository). Interpretation of models using native weights are presented in the online repository. When evaluating associations with CRSO and CRSS+O, we conducted sensitivity analysis, excluding individuals with evidence of prior sinus surgery on the CT images, as sinus surgery has the potential to cause changes to the sinuses that change L-M scores.17

RESULTS

Study population

Of the 3269 subjects invited to participate in the sinus CT study, 646 (19.8%) completed the scan. In the study sample, two-thirds were women and the mean age was 58 years, similar to the CRISP cohort from which individuals were recruited.10 (Table I).

Table I.

Characteristics of participants with completed sinus CT scans (n = 646)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 431 (66.7) |

| Male | 215 (33.3) |

| Age, years | |

| 18–39 | 57 (8.8) |

| 40–49 | 111 (17.2) |

| 50–59 | 184 (28.5) |

| 60–69 | 190 (29.4) |

| 70+ | 104 (16.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non- Hispanic white | 620 (96.0) |

| Other | 26 (4.0) |

| Migraine headache† | |

| Yes | 229 (35.4) |

| No | 417 (64.6) |

| Anxiety sensitivity index‡ | |

| High | 309 (47.8) |

| Low | 337 (52.2) |

| Asthma, self-reported physician diagnosis, ever | |

| Yes | 197 (30.5) |

| No | 449 (69.5) |

| Prior sinus surgery§ | |

| Yes | 120 (18.6) |

| No | 526 (81.4) |

| TOTAL | 646 (100.0) |

Based on questions from the ID Migraine Questionnaire

Divided at the median: high = at/above median; low = less than the median.

Evidence of sinus surgery on sinus CT.

Prevalence of CRSS, CRSO and CRSSS+O

Reviewers agreed, within one point, on 95 to 98% of the scores for the five sinus locations. In the source population analysis (native weights), 16.1% of individuals had current CRSS (Table II). An estimated 50% had an L-M score of 0, 38.6% had an L-M score of 1 – 3, and 11.2% had an L-M ≥ 4. CRSO estimates in the source population ranged from 6.6% for L-M ≥ 6 to 12.4% for L-M ≥ 3. Opacification (any versus none) was most common in the maxillary (28.6%) and anterior ethmoid (21.7%) sinuses and least common in the sphenoid (5.1%) and frontal sinuses (8.3%).

Table II.

Proportion of study participants meeting various CRS symptom and radiologic opacification definitions in study sample (unweighted) and as estimated prevalence in source population (native weights)

| Characteristic | Study Sample (n = 646) Unweighted Percent (SE) | Source Population Weighted† Percent (SE) |

|---|---|---|

| CRSS status‡ | ||

| Current (n = 324) | 50.2 (2.0) | 16.1 (1.9) |

| Past (n = 249) | 38.5 (1.9) | 24.5 (1.8) |

| Never (n = 73) | 11.3 (1.2) | 59.5 (2.0) |

| CRSO status§ | ||

| Lund-Mackay ≥ 3 (n = 168) | 26.0 (1.7) | 12.4 (2.3) |

| Lund-Mackay ≥ 4 (n = 137) | 21.2 (1.6) | 11.2 (2.3) |

| Lund-Mackay ≥ 6 (n = 89) | 13.8 (1.4) | 6.6 (1.9) |

| CRSS-O status¶ | ||

| Lund-Mackay ≥ 3 (n = 89) | 13.8 (1.4) | 3.6 (0.80) |

| Lund-Mackay ≥ 4 (n = 73) | 11.3 (1.2) | 3.2 (0.79) |

| Lund-Mackay ≥ 6 (n = 41) | 6.3 (0.96) | 1.3 (0.67) |

| Frontal sinus opacification¥ | 13.0 (1.3) | 8.3 (2.5) |

| Maxillary sinus opacification¥ | 42.6 (1.9) | 28.6 (7.1) |

| Anterior ethmoid opacitication¥ | 28.8 (1.8) | 21.7 (7.1) |

| Posterior ethmoid opacification¥ | 19.4 (1.6) | 14.7 (6.7) |

| Sphenoid opacification¥ | 9.9 (1.2) | 5.1 (1.7) |

| Ostiomeatal complex opacification¥ | 12.9 (1.3) | 8.1 (2.2) |

| Nasal cavity opacification¥ | 5.3 (0.88) | 1.6 (0.48) |

Weighted for sampling and participation rates to estimate prevalence in source population.

Never: did not report European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis (EPOS) CRS symptoms in lifetime; past: met EPOS CRS symptoms in lifetime but not currently; current: met EPOS CRS symptoms in the last 3 months.

Lund-Mackay score based on CT scoring by two otolaryngologists blinded to CRSS status.

Met criteria for current CRSS and CRSO criteria at different Lund-Mackay cut-points.

Any opacification/occlusion score >0.

Among those with evidence of radiologic inflammation, the prevalence of CRS symptoms varied by L-M score threshold (Table III). In the source population, we estimated that 28.3% of individuals with an L-M score ≥ 4 had current CRSS, 30.1% had CRSS in the past, and 41.6% had no history of CRSS. An estimated 20% of the source population with current CRSS had an L-M score ≥ 4.

Table III.

Proportion with CRSS† at different Lund-Mackay thresholds for positivity of radiologic inflammation in study sample (unweighted) and as estimated in source population (native weights)

| Study Sample (n = 646) Unweighted | Source Population Weighted‡ |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lund-Mackay score | CRSS Current | CRSS Past | CRSS Never | CRSS Current | CRSS Past | CRSS Never |

| ≥ 3 (%) | 53.0 | 37.5 | 9.5 | 29.2 | 31.9 | 39.0 |

| ≥ 4 (%) | 53.3 | 37.2 | 9.5 | 28.3 | 30.1 | 41.6 |

| ≥ 6 (%) | 46.1 | 41.6 | 12.4 | 19.7 | 32.4 | 48.0 |

Never: did not report European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis (EPOS) CRS symptoms in lifetime; past: met EPOS CRS symptoms in lifetime but not currently; current: met EPOS CRS symptoms in the last 3 months.

Weighted for sampling and participation rates back to source population

CRSO by demographic and clinical characteristics

Prior sinus surgery was associated with more sinus opacification. As estimated in the source population, the prevalence of CRSO among those with sinus surgery was over 50% (using L-M score ≥ 3 or 4), more than five times the prevalence of those without evidence of sinus surgery (Table IV). In the 646 study participants, the prevalence of CRSO in men was nearly double that of women, depending on the L-M score threshold. This trend was present in source population estimates as well, though the magnitude of the differences were attenuated. In the source population 14.6% of men and 9.9% of women were estimated to have a L-M score ≥ 4. These sex differences remained when the analysis was restricted to participants with no evidence of sinus surgery (n = 526) (Online Repository Table E2).

Table IV.

Proportion of study participants meeting various criteria for Lund-Mackay (L-M) scores by subject characteristics, in study sample (unweighted) and estimated in source population (native weights)

| Characteristic | N (%) | Study Sample (n = 646) Unweighted Percent (SE) |

Source Population Weighted† Percent (SE) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-M ≥ 3 | L-M ≥ 4 | L-M ≥ 6 | L-M ≥ 3 | L-M ≥ 4 | L-M ≥ 6 | ||

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 431 (66.7) | 20.7 (2.0)* | 15.7 (1.8)* | 10.7 (1.5)** | 11.1 (3.0) | 9.9 (3.0) | 5.7 (2.3) |

| Male | 215 (33.3) | 36.7 (3.3) | 32.1 (3.2) | 20.0 (2.7) | 16.1 (5.0) | 14.6 (4.7) | 8.7 (3.6) |

| Age, years | |||||||

| 18–39 | 57 (8.8) | 26.3 (5.8) | 21.1 (5.4) | 19.3 (5.2) | 25.5 (9.9) | 22.0 (9.5) | 21.8 (9.4)** |

| 40–49 | 111 (17.2) | 19.8 (3.8) | 15.3 (3.4) | 9.9 (2.8) | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.1 (1.1) | 1.5 (0.9) |

| 50–59 | 184 (28.5) | 27.7 (3.3) | 22.3 (3.1) | 12.0 (2.4) | 17.2 (7.8) | 15.7 (7.6) | 3.9 (2.0) |

| 60–69 | 190 (29.4) | 24.7 (3.1) | 21.6 (3.0) | 14.2 (2.5) | 14.7 (6.0) | 14.4 (6.0) | 11.5 (5.5) |

| 70+ | 104 (16.1) | 31.7 (4.6) | 25.0 (4.2) | 17.3 (3.7) | 10.2 (4.6) | 6.8 (3.0) | 2.6 (1.4) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 620 (96.0) | 26.3 (1.8) | 21.3 (1.6) | 13.7 (1.4) | 11.8 (2.3) | 10.5 (2.2) | 5.7 (1.7) |

| Non-white | 26 (4.0) | 19.2 (7.7) | 19.2 (7.7) | 15.4 (7.1) | 28.6 (21.5) | 28.6 (21.5) | 27.8 (21.5) |

| Migraine headache‡ | |||||||

| Yes | 229 (35.4) | 22.3 (2.8) | 15.7 (2.4)* | 9.2 (1.9)** | 9.6 (4.0) | 8.0 (3.5) | 4.3 (2.3) |

| No | 417 (64.6) | 28.1 (2.2) | 24.2 (2.1) | 16.3 (1.8) | 13.2 (3.0) | 12.0 (3.0) | 7.2 (2.4) |

| CRSS status§ | |||||||

| Current | 324 (50.2) | 27.5 (2.5) | 22.5 (2.3) | 12.7 (1.8) | 22.5 (4.7)** | 19.7 (4.6) | 8.0 (4.1) |

| Past | 249 (38.5) | 25.3 (2.8) | 20.5 (2.6) | 14.9 (2.3) | 16.2 (3.2) | 13.8 (2.9) | 8.7 (2.5) |

| Never | 73 (11.3) | 21.9 (4.8) | 17.8 (4.5) | 15.1 (4.2) | 8.1 (3.4) | 7.8 (3.4) | 5.3 (2.7) |

| Anxiety sensitivity index¶ | |||||||

| High | 309 (47.8) | 27.5 (2.5) | 19.6 (2.2) | 14.6 (2.0) | 21.1 (7.3)3 | 19.7 (7.1)* | 11.3 (5.4) |

| Low | 337 (52.2) | 24.6 (2.3) | 23.0 (2.4) | 13.1 (1.8) | 8.5 (1.7) | 7.4 (1.6) | 4.4 (1.4) |

| Asthma, self-reported physician diagnosis, ever | |||||||

| Yes | 197 (30.5) | 33.0 (3.4)** | 27.4 (3.2)** | 19.8 (2.8)** | 28.1 (8.8)** | 22.8 (8.5)** | 11.2 (3.5) |

| No | 449 (69.5) | 22.9 (2.0) | 18.5 (1.8) | 11.1 (1.5) | 9.6 (2.2) | 9.1 (2.2) | 5.7 (2.1) |

| Prior sinus surgery¥ | |||||||

| Yes | 120 (18.6) | 50.8 (4.6)* | 41.7 (4.5)* | 29.2 (4.2)* | 56.0 (7.4)* | 53.2 (7.7)* | 31.3 (12.6)* |

| No | 526 (81.4 | 20.3 (1.8) | 16.5 (1.6) | 10.3 (1.3) | 10.1 (2.3) | 9.1 (2.3) | 5.3 (1.8) |

| TOTAL | 646 (100.0) | 26.01 (1.7) | 21.2 (1.6) | 13.8 (1.4) | 12.4 (2.3) | 11.2 (2.3) | 6.6 (1.9) |

Weighted for sampling and participation rates back to source population.

p < 0.0001

p < 0.05

Based on questions from the ID Migraine Questionnaire.

Never: did not report European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis (EPOS) CRS symptoms in lifetime; past: met EPOS CRS symptoms in lifetime but not currently; current: met EPOS CRS symptoms in the last 3 months.

Divided at the median: high = at/above median; low = less than the median.

Evidence of sinus surgery on sinus CT.

In unadjusted analysis migraine headache was negatively associated with CRSO. The presence of asthma, current CRSS, and high ASI were positively associated with CRSO in the source population in unadjusted analysis (Table IV). Among participants with no prior sinus surgery, similar trends were observed for migraine headache and asthma, but not for CRSS and ASI (Online Repository Table E2).

CRSS+O by demographic and clinical characteristics

Similar to CRSO, in unadjusted analysis the proportion with CRSS+O differed by sex and sinus surgery history. In the source population, 7.5% of men and 1.6% of women met CRSS+O criteria (using L-M ≥ 4). More than one-third of those with a prior sinus surgery in the source population (34.5%) met CRSS+O (using L-M ≥ 4), compared to 1.6% among those without evidence of surgery. A similar trend for sex was observed among participants with no prior sinus surgery (Online Repository Table E3).

Opacification of sinus location by demographic and clinical characteristics

In the source population, in unadjusted analysis a greater proportion of men compared to women had evidence of opacification (any) in the frontal, anterior ethmoid, and sphenoid sinuses (Table V). Opacification was more common among those who did not meet (vs. met) the criteria for migraine headache, in all sinus locations except the posterior ethmoid. Prior sinus surgery (vs. none) was associated with opacification in all sinus locations. In the subgroup of non-surgical participants, men (vs. women) were more likely to have at least some opacification in all locations and those with no (vs. yes) migraine headache were more likely to have opacification in a subset of sinus locations (Online Repository Tables E4 and E5).

Table V.

Opacification of nasal or sinus location for selected participant characteristics, native weights (n = 646)†

| Estimated percent in source population with any opacification (SE)‡ | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Frontal | Maxillary | Anterior Ethmoid | Posterior Ethmoid | Sphenoid | Osteomeatal Complex | Nasal cavity opacification |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 7.6 (3.4)* | 34.0 (6.4) | 18.5 (4.9) | 13.6 (4.8) | 5.7 (3.0) | 12.4 (4.2) | 2.6 (1.0) |

| Male | 20.6 (7.2) | 32.3 (7.6) | 35.3 (8.7) | 14.5 (4.3) | 10.3 (3.7) | 9.5 (2.6) | 1.5 (0.70) |

| Migraine headache§ | |||||||

| Yes | 4.5 (2.4)* | 30.7 (5.9) | 12.1 (3.2)* | 14.6 (9.0) | 5.6 (2.7) | 9.0 (3.4) | 3.8 (2.4) |

| No | 13.7 (4.4) | 34.3 (6.1) | 27.2 (5.8) | 13.6 (3.4) | 7.6 (2.9) | 12.2 (3.4) | 1.9 (0.5) |

| CRSS¶ | |||||||

| Current | 13.8 (4.1) | 45.3 (6.5) | 23.1 (4.5) | 12.1 (4.4) | 10.1 (4.1) | 9.1 (2.8) | 1.4 (0.66) |

| Past | 12.4 (7.1) | 34.1 (8.0) | 31.4 (8.4) | 12.2 (2.9) | 5.5 (2.2) | 9.3 (2.8) | 3.8 (1.7) |

| Never | 9.9 (5.3) | 26.8 (8.8) | 18.0 (7.6) | 16.2 (7.6) | 6.9 (4.6) | 14.5 (6.6) | 1.6 (0.8) |

| Anxiety sensitivity index¥ | |||||||

| High | 18.2 (7.9) | 37.2 (7.6) | 26.5 (7.8) | 14.5 (5.8) | 10.5 (5.1) | 20.9 (6.9)** | 1.3 (0.5) |

| Low | 7.8 (2.0) | 31.4 (5.6) | 22.1 (5.4) | 13.5 (4.3) | 5.1 (1.9) | 6.0 (1.6) | 2.9 (1.1) |

| Asthma, self-reported physician diagnosis, ever | |||||||

| Yes | 9.2 (3.2) | 41.5 (10.2) | 20.4 (5.1) | 12.2 (3.2) | 7.9 (3.0) | 22.5 (8.7) | 6.8 (3.0) |

| No | 12.3 (4.3) | 31.3 (5.1) | 24.7 (5.7) | 14.3 (4.5) | 6.9 (2.9) | 8.4 (3.1) | 1.1 (0.4) |

| Prior sinus surgery£ | |||||||

| Yes | 47.7 (8.3)** | 61.6 (6.8)** | 56.0 (7.4)** | 39.9 (12.6)** | 24.8 (12.6)** | 15.1 (4.7) | 12.1 (3.8)** |

| No | 9.0 (3.6) | 31.5 (5.2) | 21.4 (4.9) | 12.0 (3.7) | 5.8 (2.3) | 11.2 (3.3) | 1.6 (0.70) |

| TOTAL | 8.3 (2.5) | 28.6 (7.1) | 21.7 (7.1) | 13.8 (1.4) | 5.1 (1.7) | 8.1 (2.2) | 1.6 (0.48) |

Weighted for sampling and participation rates, weights of 6 participants at the highest weight were truncated to next highest weight for these bivariate comparisons because of large influence on estimates.

Score on Lund-Mackay > 0

p ≤ 0.05

p < 0.01

Based on questions from the ID Migraine questionnaire.

Never: did not report European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis (EPOS) CRS symptoms in lifetime; past: met EPOS CRS symptoms in lifetime but not currently; current: met EPOS CRS symptoms in the last 3 months.

Divided at the median: high = at/above median; low = less than the median.

Evidence of sinus surgery on sinus CT.

Factors associated with integer Lund-Mackay score

In adjusted models reflected to the source population (truncated weighting), sex and sinus surgery were associated with L-M scores. Women had an average L-M score 31% lower than men (incident rate ratio, 95% confidence interval (IRR, CI): 0.69, 0.48 – 0.98) and those with prior sinus surgery had two times the average L-M score of those without (IRR, CI: 2.06, 1.28 – 3.30). Similar sex differences were observed among participants without sinus surgery (Online Repository Table E6). There was no evidence of effect modification of the association between CRSS and L-M score by sex, migraine headache status, or ASI score in the source population or when analysis was restricted to participants without prior sinus surgery (results not shown).

Factors associated with CRSS+O status

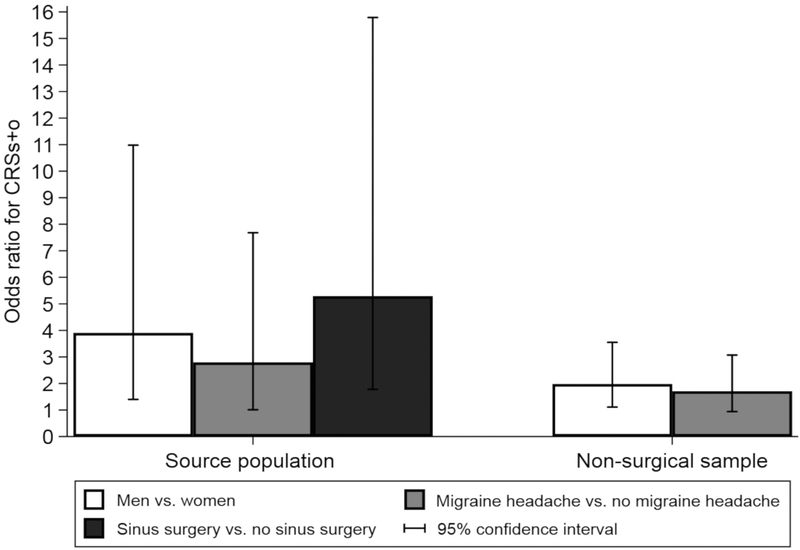

Sex, migraine headache, and sinus surgery history were associated with CRSS+O status in the source population (truncated weighting), adjusting for age and ASI (Figure I). Men had three to nearly five times the odds of CRSS+O compared to women, depending on the L-M score criterion. Subjects with prior sinus surgery had five to more than eight times the odds of CRSS+O compared to subjects with no prior sinus surgery. Those with migraine headache had 2.8 times the odds of CRSS+O compared to those without migraine headache (p < 0.05) when L-M ≥ 3 was used as the threshold for positivity. Thus, while migraine headache was not associated with radiologic inflammation in adjusted models, it was associated with the co-occurrence of inflammation and CRS symptoms. This trend was also observed at other L-M thresholds. Similar, but attenuated, sex and migraine associations were observed in analysis restricted to participants without evidence of prior sinus surgery (Figure I).

Figure I.

Associations (odds ratios) of sex, migraine headache, and prior sinus surgery with CRSS+O (CRS symptoms with Lund-Mackay ≥ 3) in the source population (646 sinus CT participants weighted for sampling and participation using truncated weights) and among participants with no evidence of prior sinus surgery on sinus CT (n = 526). Adjusted for age (centered), sex, anxiety sensitivity index, and patient-reported asthma diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

Prior reports on the epidemiology of CRS are largely based on studies that used symptoms alone to identify persons with CRS. To our knowledge, this is the first U.S. population-based study to investigate the epidemiology of CRSS+O, based on the co-occurrence of radiologic sinus inflammation and nasal and sinus symptoms. In contrast to symptom-based studies, our study found that CRSS+O is more common in men than in women. Male sex, migraine headache, and prior sinus surgery were positively associated with CRSS+O.

Prior to this study, radiologic sinus inflammation was generally studied in patients being evaluated for sinus surgery or other clinical indications. The L-M cut-off of four as the criterion for sinus surgery was originally based on the observation that the mean “normal” score in patients who undergo imaging for non-rhinologic symptoms was 4.3.4,18 In the general population, we found that 14.6% of men and 9.9% of women had an L-M score ≥ 4 (CRSO).

The prevalence of CRSS+O using an L-M score positivity criterion ≥ 4 was 7.5% for men and 1.6% for women, a large enough difference to suggest that an overall prevalence would be dependent on the proportion of men and women in the study. Two other studies, outside the U.S., have evaluated the prevalence of CRSS+O. A study in Korea used symptoms and endoscopy and reported a CRSS+O prevalence of 9.6% in men and 7.1% in women.19 The European GA2LEN study used CT images from patients who underwent CT imaging for non-rhinologic indications to estimate CRSS+O prevalence.9 Similar to our overall prevalence, the GA2LEN study had an overall prevalence of 3.0%, and a population that was over two-thirds women. Prevalence by sex was not reported. Given the overrepresentation of women and the exclusion of rhinologic patients, a prevalence of 3.0% may be an underestimate of CRS in Europe.

Prior studies reported that CRS symptoms did not differ by sex or were more prevalent in women.20–22 One hypothesis is that women, in whom migraine headache is more prevalent, may be more often misclassified as CRSS. While prior studies did not formally test this hypothesis, we accounted for sex and migraine headache status, and the odds of CRSS+O was higher in both persons with migraine headache and in males. Potential mechanisms for the migraine association are the crossover interactions of neurogenic and immunogenic inflammation or the association could be due to the overlapping symptoms of these conditions.10,23 Sex differences in CRSS+O could be due to different CRS endotypes by sex with different clinical presentations.24 Endotypes may vary in their tendency to cause radiologic opacification, a measure of inflammation observable from sinus CT scan.25,26 Future studies should explore alternative methods of measuring inflammation.27

In our study, persons with radiologic inflammation had a range of symptoms. An estimated 28% of the source population with an L-M score ≥ 4 had current CRSS, while more than 40% had no history of CRSS. Thus, radiologic inflammation does not necessarily lead to symptoms. Similarly, symptoms cannot always be attributed to sinus inflammation. An estimated 20% of the source population with current CRSS had an L-M score ≥ 4. Consistent with our findings, 23% of those with CRS symptoms in the GA2LEN study had radiologic evidence of inflammation.9 Prior studies have hypothesized that symptom overreporting may explain why many persons who meet CRSs do not have CRSo;24 such overreporting may differ by sex. However, we found no evidence that ASI (a surrogate measure for symptom over-reporting), sex, or migraine headache modified associations between CRSO and CRSS. It may also be that current approaches to measuring CRS symptoms identify other diseases that are unrelated to sinus inflammation and, thus, do not align with objective evidence of disease. Alternative approaches to symptom measurement may identify symptom subgroups differentially associated with sinus inflammation; findings that would have potential relevance to targeted disease management strategies.28

Prior sinus surgery was associated with both higher L-M scores and higher odds of CRSS+O. Sinus surgery can cause sinus changes that would be scored as opacification using L-M criteria and recurrent sinus inflammation is common after surgery.29,30 Sinus surgery may also be a surrogate for disease severity, such that individuals with the most severe disease burden are more likely to seek surgical intervention. Thus, excluding patients with prior sinus surgery or seeking sinus surgery from epidemiologic studies might fail to capture the severe end of the disease spectrum.

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to assess and report differences in the prevalence of opacification by sinus location in a population-based sample. Associations of sex and migraine with opacification differed by sinus location. Location of sinus opacification may be indicative of the pathophysiology of a CRS subtype.31 Future studies should assess how specific patterns of radiologic opacification relate to CRS phenotypes and endotypes.

This study had a number of strengths. First, we prospectively collected sinus CT scans from the general population. Prior studies have depended upon existing sinus CT scans obtained from patients in tertiary care settings who may not be representative of the full spectrum of disease. Second, we were able to account for sampling and participation rates using weighting methods. This strategy enabled us to account for potential selection and participation bias by CRS symptom status and demographic characteristics. This study had the following limitations. First, while our weighting strategy largely mitigated participation bias by symptom status assessed prior to selection into the CT study, we were unable to account for symptoms that were present at time of recruitment. If individuals with new sinus symptoms were more likely to participate, prevalence estimates may be slightly inflated. Participation rates did not differ by sex or sinus surgery history. Differences in participation by unmeasured factors were likely non-differential and would not have impacted our observed associations. Second, the findings of our study may not be generalizable to populations with different sociodemographic characteristics or from different regions of the U.S. However, our findings provide a valid estimate of the prevalence of CRS in the region studied. Finally, we measured inflammation using sinus CT, a surrogate measure. Future studies should incorporate alternative measures of inflammation.

Conclusion

Radiologic sinus inflammation was prevalent in the general population in central and northeastern Pennsylvania, and more common among men than in women. The odds of CRS meeting symptom and objective criteria was higher in men and persons with migraine headache and prior sinus surgery. There were sex differences in the sinus locations with opacification. Differences observed across sinus locations may reflect different disease endotypes that should be further explored.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank Dione Mercer, Jacob Mowery, and Caroline Price for coordinating the recruitment, collection, and scoring of sinus CT scans.

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [U19AI106683].

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement:

Dr. Hirsch reports grants from NIAID, during the conduct of the study; Dr. Bandeen-Roche reports grants from Geisinger, during the conduct of the study; grants from National Institutes of Health, grants from Centers for Disease Control, outside the submitted work; Dr. Tan reports grants from NIH, personal fees from Optinose, personal fees from Sanofi, outside the submitted work; Dr. Schleimer reports grants from NIH, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Intersect ENT, personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline, other from Allakos, other from Aurasense, personal fees from Merck, other from BioMarck, personal fees from Sanofi, personal fees from AstraZeneca/Medimmune, personal fees from Genentech, other from Exicure Inc, personal fees from Otsuka Inc, other from Aqualung Therapeutics Corp, personal fees from Actobio Therapeutics, personal fees from Lyra Therapeutics, personal fees from Astellas Pharma Inc, outside the submitted work; In addition, Dr. Schleimer has a patent Siglec-8 and Siglec-8 ligand related patents licensed to Allakos Inc.; Dr. Kern reports personal fees from Sanofi, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Lyra Pharmaceutical, personal fees from Neurent, outside the submitted work; Dr. Sundaresan reports grants from NIH, during the conduct of the study; Dr. Pinto reports personal fees from Optinose, personal fees from Genentech, personal fees from ALK, personal fees from Stallergenes, grants from NIH, outside the submitted work; Dr. Kennedy has nothing to disclose; Dr. Greene has nothing to disclose; Dr. Kuiper has nothing to disclose; Dr. Schwartz reports grants from NIAID, during the conduct of the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tan BK, Kern RC, Schleimer RP, Schwartz BS. Chronic rhinosinusitis: the unrecognized epidemic. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013. December 1;188(11):1275–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Mullol J, Bachert C, Alobid I, Baroody F, et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2012. Rhinol Suppl. 2012. March;23:3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orlandi RR, Kingdom TT, Hwang PH, Smith TL, Alt JA, Baroody FM, et al. International consensus statement on allergy and rhinology: rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016. February;6 Suppl 1:S22–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hopkins C, Browne JP, Slack R, Lund V, Brown P. The Lund-Mackay staging system for chronic rhinosinusitis: how is it used and what does it predict?. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007. October;137(4):555–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Havas TE, Motbey JA, Gullane PJ. Prevalence of incidental abnormalities on computed tomographic scans of the paranasal sinuses. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988. August;114(8):856–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lund VJ, Kennedy DW. Staging for rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997. September;117(3 Pt 2):S35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris JN. Uses of epidemiology. Br Med J. 1955. August 13;2(4936):395–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashraf N, Bhattacharyya N. Determination of the “incidental” Lund score for the staging of chronic rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001. November;125(5):483–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dietz de Loos D, Lourijsen ES, Wildeman MAM, Freling NJM, Wolvers MDJ, Reitsma S, et al. Prevalence of chronic rhinosinusitis in the general population based on sinus radiology and symptomatology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019. March;143(3):1207–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirsch AG, Stewart WF, Sundaresan AS, Young AJ, Kennedy TL, Scott Greene J, et al. Nasal and sinus symptoms and chronic rhinosinusitis in a population‐based sample. Allergy. 2017. February;72(2):274–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu AY, Curriero FC, Glass TA, Stewart WF, Schwartz BS. The contextual influence of coal abandoned mine lands in communities and type 2 diabetes in Pennsylvania. Health Place. 2013. July;22:115–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lipton RB, Dodick D, Sadovsky R, Kolodner K, Endicott J, Hettiarachchi J, et al. A self-administered screener for migraine in primary care: The ID Migraine validation study. Neurology. 2003. August 12;61(3):375–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sundaresan AS, Hirsch AG, Young AJ, Pollak J, Tan BK, Schleimer RP, et al. Longitudinal Evaluation of Chronic Rhinosinusitis Symptoms in a Population-based Sample. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018. Jul-Aug;6(4):1327–1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodriguez BF, Bruce SE, Pagano ME, Spencer MA, Keller MB. Factor structure and stability of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index in a longitudinal study of anxiety disorder patients. Behav Res Ther. 2004. January;42(1):79–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chowdhury S, Khare M, Wolter K. Weight trimming in the national immunization survey. Proceedings of the Joint Statistical Meetings, Section on Survey Research Methods, American Statistical Association 2007. July 29;26512658:2651–2658. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Little R, Lewitzky S, Heeringa S, Lepkowski J, Kessler RC. Assessment of weighting methodology for the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 1997. September 1;146(5):439–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhattacharyya N. Computed tomographic staging and the fate of the dependent sinuses in revision endoscopic sinus surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999. September;125(9):994–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhattacharyya N, Fried MP. The accuracy of computed tomography in the diagnosis of chronic rhinosinusitis. The Laryngoscope. Laryngoscope. 2003. January;113(1):125–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahn JC, Kim JW, Lee CH, Rhee CS. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic rhinosinusitus, allergic rhinitis, and nasal septal deviation: results of the Korean National Health and Nutrition Survey 2008–2012. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016. February;142(2):162–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hastan D, Fokkens WJ, Bachert C, Newson RB, Bislimovska J, Bockelbrink A, et al. Chronic rhinosinusitis in Europe--an underestimated disease. A GA2LEN study. Allergy. 2011. September;66(9):1216–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pleis JR, Lucas JW, Ward BW. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2008. Vital Health Stat 10 2009. December;(242):1–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Dales R, Lin M. The epidemiology of chronic rhinosinusitis in Canadians. Laryngoscope. 2003. July;113(7):1199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cady RK, Schreiber CP. Sinus headache or migraine? Neurology 2002;58(9, suppl 6):S10–S14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ference EH, Tan BK, Hulse KE, Chandra RK, Smith SB, Kern RC, et al. Commentary on gender differences in prevalence, treatment, and quality of life of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy Rhinol (Providence). 2015. January;6(2):82–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lam M, Hull L, McLachlan R, Snidvongs K, Chin D, Pratt E, et al. Clinical severity and epithelial endotypes in chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2013. February;3(2):121–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bachert C, Akdis CA. Phenotypes and emerging endotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016. Jul-Aug;4(4):621–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akdis CA, Bachert C, Cingi C, Dykewicz MS, Hellings PW, Naclerio RM, et al. Endotypes and phenotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis: a PRACTALL document of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013. June;131(6):1479–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cole M, Bandeen‐Roche K, Hirsch AG, Kuiper JR, Sundaresan AS, Tan BK, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of clustering of chronic sinonasal and related symptoms using exploratory factor analysis. Allergy. 2018. August;73(8):1715–1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stankiewicz JA, Lal D, Connor M, Welch K. Complications in endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis: a 25‐year experience. Laryngoscope. 2011. December;121(12):2684–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamilos DL. Chronic rhinosinusitis: epidemiology and medical management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011. October;128(4):693–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sedaghat AR, Bhattacharyya N. Radiographic density profiles link frontal and anterior ethmoid sinuses behavior in chronic rhinosinusitis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2012. November;2(6):496–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.