Abstract

Hydatid disease or echinococcosis is a zoonotic parasitic disease. The lung is the second most commonly affected organ after the liver. Intra-thoracic and extra-pulmonary hydatid disease is uncommon and may involve the pleura, mediastinum, heart, diaphragm, and chest wall. Unusual locations or complications of thoracic hydatid disease may pose a diagnostic challenge. We present imaging findings of cases with unusual location and presentations of thoracic hydatid disease with emphasis on their clinical implications.

Keywords: Hydatid, Thoracic, Cysts, Imaging, Unusual, Extra-pulmonary

Core tip: Hydatid disease is a parasitic zoonosis which is prevalent in sheep-rearing regions of the world. The thoracic cavity can be affected by hydatid cysts in multiple different ways. Although lungs are the most common affected site, hydatid cyst can be located in any part of the chest. Unusual location or complications can pose a diagnostic challenge and may influence treatment options. Radiologists and clinicians should be aware of the imaging manifestations of hydatid disease and consider the diagnosis upon encountering unusual cystic lesions in the chest, particularly in patients who lived in endemic areas or have evidence of hydatid disease elsewhere in the body

INTRODUCTION

Hydatid disease or echinococcosis is a zoonotic disease transmitted from animals to humans. It is caused by tapeworm parasites and most prevalent in rural sheep-raising areas of the Middle East, Mediterranean regions, South America, Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. Human disease is most commonly caused by echinococcus granulosus and rarely echinococcus multilocularis. Dogs and sheep are the most common primary and intermediate hosts respectively, and human transmission is caused after ingestion of food or water contaminated with the parasite’s eggs, or by direct handling of animal hosts[1-3].

Hydatid disease may affect any organ-system and anatomical site of the human body. The liver is most commonly affected site in about 75% of cases followed by the lungs. Hydatid cysts may cause symptoms due to direct mass effect or complications related to cyst rupture or superinfection[1,2]. Cyst rupture may result in life-threatening anaphylactic reactions due to the antigenic properties of the cyst fluid[3,4]. Intra-thoracic and extra-pulmonary hydatid disease is uncommon and may involve the pleura, mediastinum, heart, diaphragm, and chest wall[1,2].

Unusual locations or complications of hydatid disease in the chest may pose a diagnostic challenge or influence treatment options. The aim of this article is to review imaging findings of unusual locations and complications of hydatid disease involving the chest with emphasis on clinical implications.

HYDATID CYST STRUCTURE AND PATHOGENESIS

Understanding the structure of Hydatid cyst and review of the parasite’s life cycle is relevant to understanding imaging findings and pathogenesis of disease spread. Hydatid cyst is composed of the outer pericyst, the middle ectocyst, and the inner endocyst. The outer pericyst is a dense fibrous protective shell around the parasite that is formed by the reactive inflammatory host tissue. The acellular elastic laminated middle membrane is the ectocyst. The endocyst is the inner single germinal epithelial layer. The endocyst may form internal protrusions that eventually become daughter cysts within the larger mother cyst[1,3].

The echinococcus granulosus life cycle requires both a definitive canine host (most commonly dogs) and an intermediate host (usually sheep). Echinococcus granulosus eggs are excreted into the host faeces. Humans can become accidental hosts after ingesting food or water contaminated with parasite eggs. The larvae get released from the ingested eggs and gain access to the liver through the intestinal mucosa via mesenteric veins and the portal vein. About 75% of hydatid infections affect the liver. In about 15% of the cases, larvae bypass the liver filtration to gain access to the lungs. Hematogenous spread of echinococcus granulosus to any part of the body can also occur[1,3].

CLINICAL OVERVIEW OF EXTRAPULMONARY AND INTRATHORACIC HYDATID CYSTS

The extrapulmonary intrathoracic hydatid cysts may be silent with no symptoms and may present with symptoms commonly related to mass effect and compression of adjacent organs. Hydatid cyst rupture can cause anaphylactic shock and even death. Imaging findings of hydatid cysts are variable, ranging from purely cystic lesions to solid appearing lesions. Diagnosis of such cases can be challenging and usually based on clinical data including history of exposure or immigration from endemic area as well as supportive radiologic and serology findings[2,5,6]. Casoni’s intradermal skin test and indirect haemagglutination test (IHA) may detect the presence of antibodies to the parasite. Casoni’s intradermal test is still used for its simplicity, though it has a variable sensitivity (57%–93%) and limited specificity. The IHA test is one of the most sensitive serological tests for the diagnosis of hydatid disease. IHA test reported sensitivity ranging from 66% to 100% and it is used as a screening test[7]. Percutaneous transthoracic aspiration should be avoided or performed with caution, because it may result is allergic reactions or cause spreading of disease. Surgical removal of hydatid cyst is the treatment of choice for most patients. Medical therapy with mebendazole or albendazole is used as a complement to surgical treatment. Medical therapy is a primary treatment in patients with recurrent hydatidosis, patients who may not tolerate surgery, or patients with small cysts[5,6].

IMAGING FINDINGS

Hydatid cysts are generally classified into four types based on their imaging appearance[2].

Type I or simple cysts

Simple hydatids cysts appear as well-defined and anechoic masses on ultrasound and may include hydatid sand and septa. On computed tomography (CT), they are homogeneous lesions of fluid attenuation. On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), simple hydatid cysts show fluid signal intensity with homogeneous low signal on T1-weighted images and high signal on T2-weighted images, and have a dark rim on both sequences.

Type II or cysts with daughter cysts and cyst matrix

Daughter cysts appear as smaller cysts within the largest mother cyst. On imaging, daughter cysts are commonly located peripherally within the mother cyst. Daughter cysts tend to be lower in attenuation on CT and iso-intense or hypointense compared to the maternal matrix. Occasionally, daughter cysts can be irregular in shape and occupy most of the mother cyst. The higher attenuation surrounding maternal matrix fluid may resemble septae, resulting in a “rosette” appearance.

Type III or calcified cysts

Total calcification of hydatid cysts reflects death of hydatid cysts. Calcifications appear as echogenic areas on ultrasound with posterior shadowing, hyperattenuated areas on CT, and hypo-intense areas on MRI.

Type IV or complicated Cysts

Complications of hydatid cysts include rupture and/or superinfection. Cyst degeneration, response to treatment, or trauma are suggested etiologies of cyst rupture. Hydatid cyst rupture can be contained or communicate with surrounding structures. In contained rupture, floating membranes can manifest as serpentine linear structures of low attenuation on CT and low signal on MRI within the cyst matrix. This imaging sign is highly suggestive of hydatid cyst and has earned the moniker ‘‘water-lily sign''. The presence of intra-cystic air suggests direct or communicating rupture with or without superimposed infection.

MEDIASTINAL HYDATID CYST

Hydatid cyst involving the mediastinum is very uncommon with reported incidence of 2.6% in patients with hydatid disease. Mediastinal hydatid cysts can be primary with no evidence of other organ involvement or a result of ruptured lung hydatid cyst[8]. Primary intra-thoracic extra pulmonary hydatid cyst can be explained by hematogenous spread of hydatid scolices that bypass the filtration processes in both liver and lung, or via diaphragmatic lymphatic drainages to parasternal lymph nodes anteriorly or intercostal lymph nodes posteriorly[9].

The mediastinal hydatid cysts can cause symptoms depending on the size and location of the cyst and the involvement or mass effect on adjacent structures. Presenting symptoms are non-specific and may include chest pain, cough, shortness of breath, and dysphagia. Chest pain is reported as a common presenting symptom of mediastinal hydatid cysts. Hydatid cysts can be solitary or multiple and can involve anterior, middle, or posterior mediastinal compartments, though the posterior mediastinum is most commonly affected[8].

Cross sectional imaging with CT and MRI provides valuable diagnostic information about the cysts including morphologic features, densities, signal changes, locations, and relationship with surrounding structures. On imaging, hydatid cysts in the mediastinum can have variable imaging appearances ranging from unilocular cyst to multivesicular cyst with or without calcification. Calcifications are better detected on CT. The inherent superior contrast resolution of MRI for cystic lesions makes it invaluable in assessing for the presence of daughter cysts and resolving them from the mother cyst matrix (Figure 1)[2].

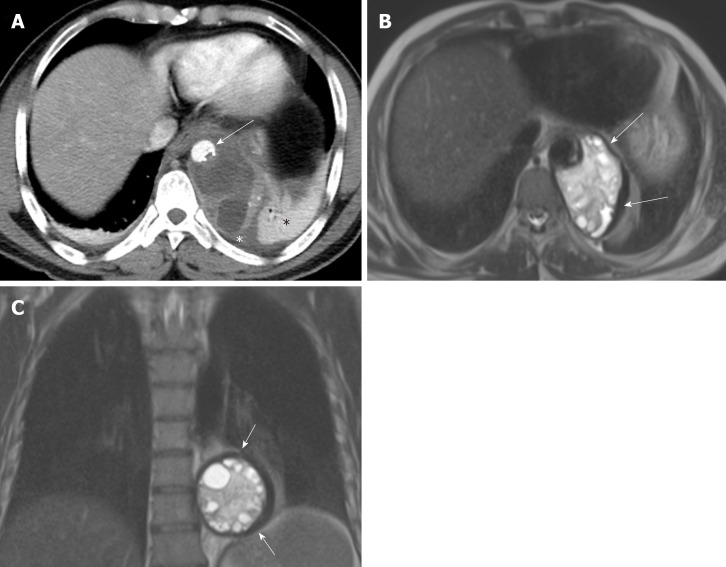

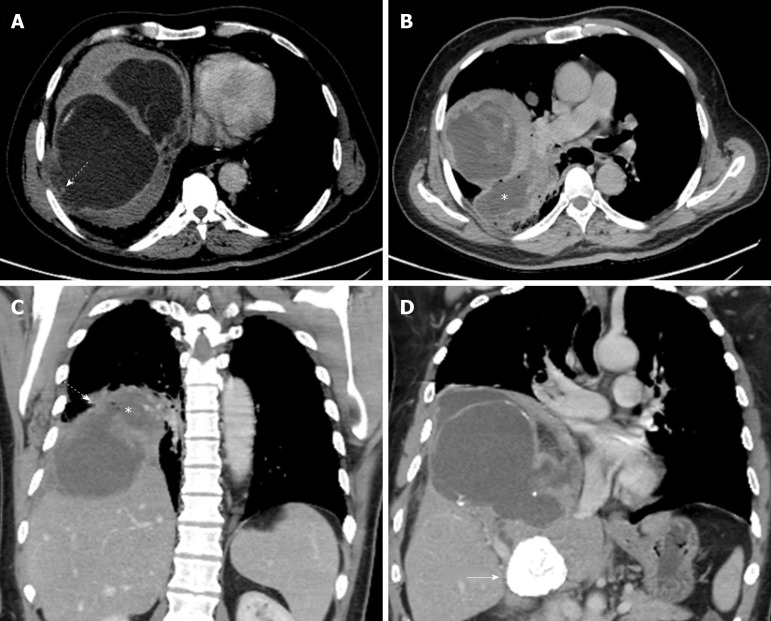

Figure 1.

A 48-year old male with mediastinal hydatid cyst presented with acute chest pain. A: Axial image of enhanced computed tomography angiogram shows a complex cystic lesion with thick wall (white arrows) that is predominately located in the left side of the posterior mediastinum with evidence small calcifications at the periphery of the lesions at the site of abutment with descending thoracic aorta. There is adjacent pleural effusion (white asterisk) and enhancing left lower lobe atelectasis (white asterisk); B, C: Axial and coronal T2 weighted images show a complex cystic lesion with thick dark rim (arrows) abutting the descending thoracic aorta with multiple peripheral daughter cysts of higher signal intensity compared to the intermediately hyperintenese matrix of the mother cyst. Magnetic resonance imaging findings are highly suggestive of hydatid cyst, likely primary given absence of evidence of lung and liver hydatid disease.

Hydatid disease should be considered in the differential diagnosis of mediastinal cystic lesion especially in patients from an endemic area or if associated with hydatid cysts elsewhere in the body[8]. Hydatid cysts in the mediastinum should be differentiated from other mediastinal cystic lesions such as benign congenital cysts (i.e., bronchogenic, esophageal duplication, neuroenteric, pericardial, and thymic cysts), meningocele, mature cystic teratoma, and lymphangioma, as well as tumors with predominant necrotic or cystic components such as thymomas, germ cell tumors, and mediastinal carcinomas[10].

Treatment of mediastinal hydatid cyst is usually surgical and includes cystectomy with total or partial pericystectomy. The surgical approach depends of the cyst location and involvement of any associated surrounding structures[8].

PULMONARY ARTERY EMBOLIZATION OF HYDATID CYSTS

Pulmonary arterial embolization of hydatid cysts is a rare complication. Hepatic echinococci may rupture into the inferior vena cava, and daughter vesicles may cause embolisms in the pulmonary arteries spontaneously or during liver surgery[11,12]. Right sided cardiac hydatid cysts can rupture directly into the pulmonary arteries[1,13]. Pulmonary embolism with hydatid cysts can present acutely with coughing, hemoptysis, and chest pain[13,14] while some cases may present with subacute presentation and may develop pulmonary hypertension[14].

Diagnosis can be made on pulmonary CT angiography where non enhancing hydatid cysts cause widening of the lumen of pulmonary arteries. MRI displays the cystic nature of lesions better than CT. Cystic nature of the pulmonary artery filling defects as well as the lack of enhancement distinguish this entity from pulmonary thromboembolism and primary or secondary pulmonary arterial tumors (Figure 2). The presence of associated cardiac or hepatic hydatid cysts are supportive findings[12,15,16]. Though surgical treatment may be recommended for low risk patients, some patients have been treated medically with variable outcomes (resolution, stability, or development of pulmonary hypertension)[15-17].

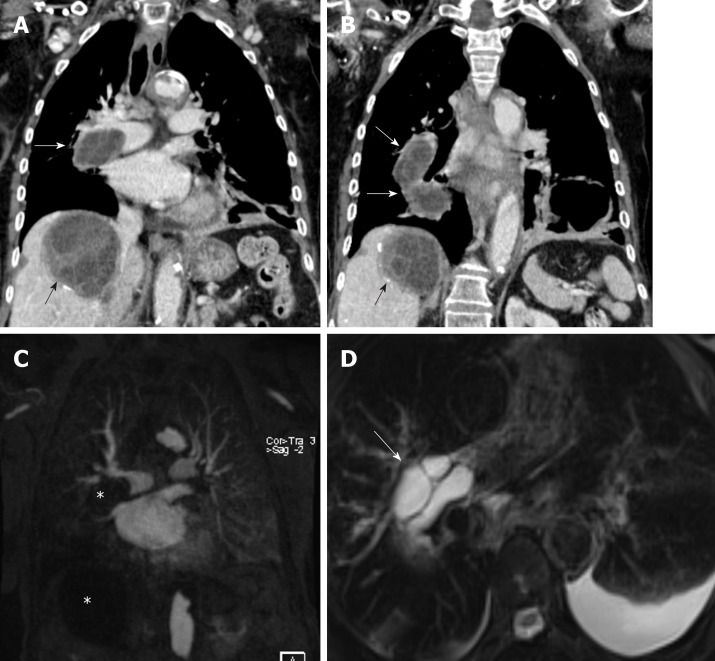

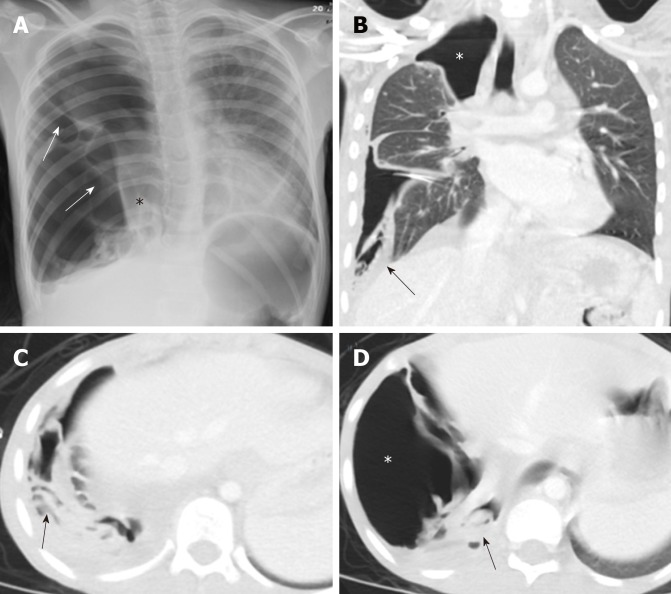

Figure 2.

An 82-year-old female with pulmonary artery hydatid cyst embolism presented with shortness of breath. A, B: Coronal images of enhanced computed tomography scan show right main pulmonary artery intra-luminal cystic filling defects causing expansion and near occlusion of the artery with extension into the right interlobar pulmonary artery (white arrows). There is hepatic hydatid cyst with internal septation and daughter cysts and scattered wall calcifications (black arrows); C: Coronal image of T1 weighted magnetic resonance angiography confirms the presence of filling defect of low signal intensity within the right pulmonary artery and low signal intensity liver lesion (asterisks) with no evidence of contrast enhancement; D: Axial T2 weighted image with fat saturation shows right main pulmonary artery intra-luminal cystic filling defects of high signal intensity with septations suggestive of daughter cysts (arrow). Left pleural effusion is noted.

CARDIAC HYDATID CYST

Cardiac involvement by hydatid disease is rare with reported incidence of 0.23% out of 842 thoracic hydatid disease cases[18]. The cardiac hydatid cysts can be asymptomatic or result in symptoms related to localization, size, and complications. Symptoms are non-specific and may include chest pain, dyspnea, and palpitations. Cardiac hydatid disease depending on location, can cause acute ischemic stroke, arrhythmias, pericardial reaction and pain, and pulmonary hypertension[19-22].

The left ventricle is the most frequently involved site (50%–60%), though the interventricular septum, right ventricle, pericardium (Figure 3), and atria can be involved[2,14]. The cysts may be single or multiple, uniloculated or multiloculated, and thin or thick walled. Presences of calcification of the cyst wall, daughter cysts, and detached floating membranes are suggestive imaging features of hydatid cysts[23]. The hydatid cysts can simulate solid mass on imaging and can be difficult to differentiate from heart tumors[24]. Transthoracic echocardiography can suggest the initial diagnosis. CT and MRI can provide additional details of the location and extension of intra-cardiac hydatid cysts. CT best shows wall calcification. MRI delineates the exact anatomic location and signal characteristic of the internal and external structures (Figure 3). MRI can depict characteristic cystic appearance with low-signal and high-signal changes on T1W and T2W images respectively, and a hypo-intense peripheral ring on T2 weighted images which represents the pericyst[23,25]. Intra-cardiac hydatid cyst may lead to severe symptoms or even sudden death due to complications, and treatment is usually surgical[14].

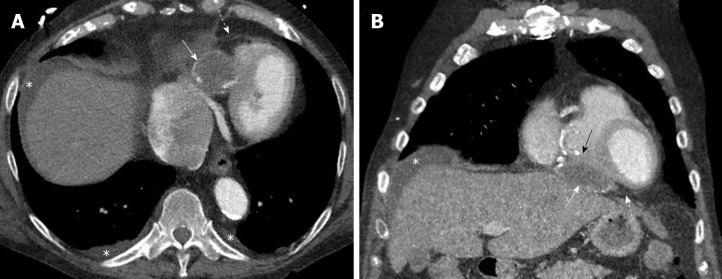

Figure 3.

Pericardial hydatid cyst. A, B: Axial and coronal contrast enhanced computed tomography images show a partially peripherally calcified cystic lesion (white arrows) along the inferior aspect of the heart and within the pericardial sac (dashed arrows) with mild mass effect and displacement of the right ventricle (black arrow). Small pleural effusions and ascites are shown (asterisks).

TRANS-DIAPHRAGMATIC EXTENSION

Hepatic hydatid disease with diaphragmatic involvement or extension into the thoracic cavity is reported in 0.16%-16% of cases[26]. The lack of a peritoneal covering over the bare area of the liver makes it less resistant to cyst growth and more vulnerable for trans-diaphragmatic extension of hepatic hydatid cysts[1]. The presence of air within hepatic or diaphragmatic hydatid cysts should raise the possibility of bronchial communication especially if associated with parenchymal findings in the adjacent lung. Associated pleural effusions, atelectasis, or pulmonary consolidation are suggestive findings of thoracic involvement[4,27].

CT scan is valuable for detection and assessment of trans-diaphragmatic extension and extension of hepatic hydatid cysts into the thoracic cavity[26,28]. Multi-planar imaging with sagittal and coronal reconstruction is very helpful in depicting trans-diaphragmatic extension[1] and plays a role in accurate pre-surgical planning. There are proposed surgical grading of diaphragmatic or trans-diaphragmatic thoracic involvement in hepatic hydatid disease based on the degree of cyst evolution and involvement[26]. Firm adherence between the diaphragm and the cyst surface without diaphragmatic perforation reflects grade 1. Diaphragmatic perforation with minimal invasion of the thoracic cavity is grade 2 (Figure 4). Grade 3 involves diaphragmatic perforation associated with either cyst growth inside the thoracic cavity or daughter vesicle formation. Involvement of the lung parenchyma either by communication between the cyst and the bronchial tree or compression of the lung parenchyma is considered grade 4[26]. Formation of a broncho-biliary communication and fistula formation reflects grade 5 (Figure 5). Hydatid daughter cysts may be expectorated with sputum. Bile expectoration is a clinical warning sign of broncho-biliary fistula. Preoperative diagnosis of trans-thoracic extension with broncho-biliary fistula will potentially alter the surgical approach as a transthoracic approach is generally preferred in such cases. The surgical approach is complex and may include bronchial fistula ligation, lung segmentectomy or lobectomy, decortication, and diaphragmatic repair, as well as treatment of the underlying hepatic hydatid cysts. Placement of abdominal and thoracic drainage tubes may be necessitated[29,30].

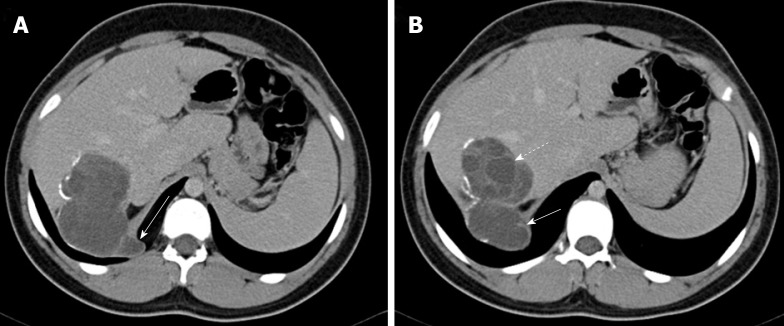

Figure 4.

Hepatic hydatid cyst complicated by trans-diaphragmatic rupture in a 17 year old male patient. A, B: Axial contrast enhanced computed tomography images show a segment 7 cyst with scattered wall calcifications and multiple daughter cysts (dashed arrow). There is cyst perforation through the right hemi-diaphragm with little invasion of the thoracic cavity (arrows).

Figure 5.

A 42-year old male presented with liver hydatid cyst complicated by broncho-biliary fistula presented with coughing bile. Axial and coronal computed tomography scan images using liver window (A) and standard soft tissue window (B-D) show intercommunicating multiple liver cystic lesions with internal non-enhancing septations and peripheral calcifications within hepatic segments 8 and 7. The right lower lobe lung cystic lesion (asterisks) contains multiple air foci indicating bronchial communication with evidence of wide communication with the hepatic cystic lesion through the diaphragmatic defect (dashed arrows in A and C). A calcified hepatic lesion near the porta hepatis represents a healed hydatid cyst (arrow in D).

INTRA-PLEURAL RUPTURE OF HYDATID CYST

Lung tissue is mostly filled by air and allows hydatid cysts to increase in size particularly in children. Rupture is not an uncommon complication and more frequent in children (reported 26.7%)[31]. Rupture can occur spontaneously when cyst increases to 7–10 cm in diameter or secondary to infection or trauma[32]. Allergic reaction like urticaria or anaphylactic shock is rare complication of hydatid cyst rupture. Pulmonary hydatid cyst rupture can be contained or communicate with the bronchial tree or pleural cavity[31]. Pleural necrosis secondary to pressure from peripherally located pulmonary cysts likely plays a role in the rupture of cysts into the pleural cavity[33]. Chest pain, cough, shortness of breath, fever, sputum production and hemoptysis have been reported in patients with pleural hydatid disease with the latter two symptoms likely related to concomitant rupture to airways[34].

Rupture into pleural cavity can present with pleural effusion, pneumothorax or hydropneumothorax, empyema, pleural thickening, collapsed lung, and bronchopleural fistula[34,35]. Ruptured hydatid cysts into the pleura can pose a diagnostic challenge for both radiologists and clinicians, especially if presenting acutely with no available prior images or evidence to suggest hepatic or lung hydatidosis. It can be misdiagnosed as empyema due to other infection such as tuberculosis[31,35].

Chest radiographs are usually the initial imaging exam and my show pleural effusion, pneumothorax, hydropneumothorax, and lung opacities. Lung opacities may represent atelectasis, pneumonia, or ruptured infected hydatid cysts. Chest CT exam are valuable in demonstrating pleural thickening and lung or pleural cysts, although ruptured cysts may collapse after spillage of cyst contents into the pleural cavity (Figure 6)[34,35]. MRI may demonstrate detached membranes within the ruptured pleural cysts[36]. The definitive diagnosis of intra-pleural rupture of hydatid cyst is sometimes made intra-operatively[35].

Figure 6.

A 10-year old female with spontaneous ruptured lung hydatid cyst presenting with pneumothorax and complicated by broncho-pleural fistula. Patient presented with oxygen desaturation and chest pain with chronic history of shortness of breath and cough for 3 months. A: Frontal chest radiograph shows large right-sided pneumothorax with small pleural effusion and multiple pleural septations (arrows), medially displaced collapsed right lung (asterisk), mild contralateral shift of the mediastinum to the left, and flattening of the right hemidiaphragm; B-D: Coronal and axial images of chest computed tomography scan after placement of chest tube show improvement of lung aeration with persistent large right-sided pneumothorax (asterisks) which suggest broncho-plural fistula, multiple collapsed membranes (arrows), and adjacent plural effusion.

The primary treatment of pleural hydatid disease is surgical intervention. Cystostomy or cystectomy and capitonnage (obliterating the cavity by suturing the cavity walls) are commonly performed with or without pleural decortication[34,35]. Bronchopleural fistula can be identified intraoperatively and subsequently repaired[35]. Pulmonary resections (segmentectomy or lobectomy) is occasionally performed when the pulmonary parenchyma adjacent to the cyst is destroyed, unable to expand, or both[34].

CONCLUSION

The thoracic cavity can be affected by hydatid cysts in different ways. Although lungs are the most common affected site, hydatid cyst can be located in any part of the chest. Unusual location or complications can pose a diagnostic challenge and may influence treatment options. Radiologists and clinicians should consider hydatid disease when they encounter unusual cystic lesions in the chest especially in patients who lived in endemic areas or have evidence of hydatid disease elsewhere in the body.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: There is no conflict of interest.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: December 25, 2019

First decision: January 17, 2020

Article in press: March 22, 2020

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kung WM, Raja S S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A E-Editor: Xing YX

Contributor Information

Mnahi Bin Saeedan, Department of Radiology, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, Riyadh 11211, Saudi Arabia.

Ibtisam Musallam Aljohani, Department of Radiology, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, Riyadh 11211, Saudi Arabia.

Khalefa Ali Alghofaily, Medical Imaging Department, Qassim University, College of Medicine, Buraydah 52571, Saudi Arabia.

Shukri Loutfi, Medical Imaging Department, Chest Radiology Section, King Abdulaziz Medical City, Riyadh 12746, Saudi Arabia.

Subha Ghosh, Imaging Institute, Section of Thoracic Imaging, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44195, United States. ghoshs2@ccf.org.

References

- 1.Pedrosa I, Saíz A, Arrazola J, Ferreirós J, Pedrosa CS. Hydatid disease: radiologic and pathologic features and complications. Radiographics. 2000;20:795–817. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.3.g00ma06795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Polat P, Kantarci M, Alper F, Suma S, Koruyucu MB, Okur A. Hydatid disease from head to toe. Radiographics. 2003;23:475–494; quiz 536-537. doi: 10.1148/rg.232025704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewall DB. Hydatid disease: biology, pathology, imaging and classification. Clin Radiol. 1998;53:863–874. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(98)80212-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marti-Bonmati L, Menor Serrano F. Complications of hepatic hydatid cysts: ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance diagnosis. Gastrointest Radiol. 1990;15:119–125. doi: 10.1007/BF01888753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ulkü R, Eren N, Cakir O, Balci A, Onat S. Extrapulmonary intrathoracic hydatid cysts. Can J Surg. 2004;47:95–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thameur H, Abdelmoula S, Chenik S, Bey M, Ziadi M, Mestiri T, Mechmeche R, Chaouch H. Cardiopericardial hydatid cysts. World J Surg. 2001;25:58–67. doi: 10.1007/s002680020008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gonlugur U, Ozcelik S, Gonlugur TE, Celiksoz A. The role of Casoni's skin test and indirect haemagglutination test in the diagnosis of hydatid disease. Parasitol Res. 2005;97:395–398. doi: 10.1007/s00436-005-1473-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eroğlu A, Kürkçüoğlu C, Karaoğlanoğlu N, Tekinbaş C, Kaynar H, Onbaş O. Primary hydatid cysts of the mediastinum. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;22:599–601. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00398-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isitmangil T, Toker A, Sebit S, Erdik O, Tunc H, Gorur R. A novel terminology and dissemination theory for a subgroup of intrathoracic extrapulmonary hydatid cysts. Med Hypotheses. 2003;61:68–71. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(03)00108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeung MY, Gasser B, Gangi A, Bogorin A, Charneau D, Wihlm JM, Dietemann JL, Roy C. Imaging of cystic masses of the mediastinum. Radiographics. 2002;22 Spec No:S79–S93. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.22.suppl_1.g02oc09s79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Röthlin MA. Fatal intraoperative pulmonary embolism from a hepatic hydatid cyst. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:2606–2607. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Damiani MF, Carratù P, Tatò I, Vizzino H, Florio C, Resta O. Recurrent pulmonary embolism due to echinococcosis secondary to hepatic surgery for hydatid cysts. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2012;36:534–535. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e318264e618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bayraktaroglu S, Ceylan N, Savaş R, Nalbantgil S, Alper H. Hydatid disease of right ventricle and pulmonary arteries: a rare cause of pulmonary embolism--computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings (2009: 5b) Eur Radiol. 2009;19:2083–2086. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-1165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kardaras F, Kardara D, Tselikos D, Tsoukas A, Exadactylos N, Anagnostopoulou M, Lolas C, Anthopoulos L. Fifteen year surveillance of echinococcal heart disease from a referral hospital in Greece. Eur Heart J. 1996;17:1265–1270. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akgun V, Battal B, Karaman B, Ors F, Deniz O, Daku A. Pulmonary artery embolism due to a ruptured hepatic hydatid cyst: clinical and radiologic imaging findings. Emerg Radiol. 2011;18:437–439. doi: 10.1007/s10140-011-0953-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Namn Y, Maldjian PD. Hydatid cyst embolization to the pulmonary artery: CT and MR features. Emerg Radiol. 2013;20:565–568. doi: 10.1007/s10140-013-1130-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salem R, Zrig A, Joober S, Trimech T, Harzallah W, Jellali MA, Mnari W, Saad J, Hmida B, Elkamel A, Golli M. Pulmonary embolism in echinococcosis: two case reports and literature review. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2011;105:85–89. doi: 10.1179/136485911X12899838413466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qian ZX. Thoracic hydatid cysts: a report of 842 cases treated over a thirty-year period. Ann Thorac Surg. 1988;46:342–346. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)65941-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan M, Demirtas M, Cimen S, Ozler A. Cardiac hydatid cysts with intracavitary expansion. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71:1587–1590. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02443-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guven A, Sokmen G, Yuksel M, Kokoglu OF, Koksal N, Cetinkaya A. A case of asymptomatic cardiopericardial hydatid cyst. Jpn Heart J. 2004;45:541–545. doi: 10.1536/jhj.45.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Acartürk E, öZeren A, Koç M, Yaliniz H, Biçakci S, Demir M. Left ventricular hydatid cyst presenting with acute ischemic stroke: case report. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2004;17:1009–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2004.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pakis I, Akyildiz EU, Karayel F, Turan AA, Senel B, Ozbay M, Cetin G. Sudden death due to an unrecognized cardiac hydatid cyst: three medicolegal autopsy cases. J Forensic Sci. 2006;51:400–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2006.00056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dursun M, Terzibasioglu E, Yilmaz R, Cekrezi B, Olgar S, Nisli K, Tunaci A. Cardiac hydatid disease: CT and MRI findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:226–232. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ben-Hamda K, Maatouk F, Ben-Farhat M, Betbout F, Gamra H, Addad F, Fatima A, Abdellaoui M, Dridi Z, Hendiri T. Eighteen-year experience with echinococcosus of the heart: clinical and echocardiographic features in 14 patients. Int J Cardiol. 2003;91:145–151. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(03)00032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kotoulas GK, Magoufis GL, Gouliamos AD, Athanassopoulou AK, Roussakis AC, Koulocheri DP, Kalovidouris A, Vlahos L. Evaluation of hydatid disease of the heart with magnetic resonance imaging. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1996;19:187–189. doi: 10.1007/BF02577618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gómez R, Moreno E, Loinaz C, De la Calle A, Castellon C, Manzanera M, Herrera V, Garcia A, Hidalgo M. Diaphragmatic or transdiaphragmatic thoracic involvement in hepatic hydatid disease: surgical trends and classification. World J Surg. 1995;19:714–719; discussion 719. doi: 10.1007/BF00295911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alghofaily KA, Saeedan MB, Aljohani IM, Alrasheed M, McWilliams S, Aldosary A, Neimatallah M. Hepatic hydatid disease complications: review of imaging findings and clinical implications. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2017;42:199–210. doi: 10.1007/s00261-016-0860-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kilani T, El Hammami S, Horchani H, Ben Miled-Mrad K, Hantous S, Mestiri I, Sellami M. Hydatid disease of the liver with thoracic involvement. World J Surg. 2001;25:40–45. doi: 10.1007/s002680020006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Athanassiadi K, Kalavrouziotis G, Loutsidis A, Bellenis I, Exarchos N. Surgical treatment of echinococcosis by a transthoracic approach: a review of 85 cases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1998;14:134–140. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(98)00144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tocchi A, Mazzoni G, Miccini M, Drumo A, Cassini D, Colace L, Tagliacozzo S. Treatment of hydatid bronchobiliary fistulas: 30 years of experience. Liver Int. 2007;27:209–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balci AE, Eren N, Eren S, Ulkü R. Ruptured hydatid cysts of the lung in children: clinical review and results of surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:889–892. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03785-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sadrieh M, Dutz W, Navabpoor MS. Review of 150 cases of hydatid cyst of the lung. Dis Chest. 1967;52:662–666. doi: 10.1378/chest.52.5.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ozer Z, Cetin M, Kahraman C. Pleural involvement by hydatid cysts of the lung. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1985;33:103–105. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1014097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aribas OK, Kanat F, Gormus N, Turk E. Pleural complications of hydatid disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;123:492–497. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.119341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puri D, Mandal AK, Kaur HP, Mahant TS. Ruptured hydatid cyst with an unusual presentation. Case Rep Surg. 2011;2011:730604. doi: 10.1155/2011/730604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emlik D, Kiresi D, Sunam GS, Kivrak AS, Ceran S, Odev K. Intrathoracic extrapulmonary hydatid disease: radiologic manifestations. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2010;61:170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.carj.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]