Abstract

Cannabis use is of increasing public health interest globally. Here we examined the effect of heavy cannabis use, with and without tobacco, on genome-wide DNA methylation in a longitudinal birth cohort (Christchurch Health and Development Study, CHDS). A total of 48 heavy cannabis users were selected from the CHDS cohort, on the basis of their adult exposure to cannabis and tobacco, and DNA methylation assessed from whole blood samples, collected at approximately age 28. Methylation in heavy cannabis users was assessed, relative to non-users (n = 48 controls) via the Illumina Infinium® MethylationEPIC BeadChip. We found the most differentially methylated sites in cannabis with tobacco users were in the AHRR and F2RL3 genes, replicating previous studies on the effects of tobacco. Cannabis-only users had no evidence of differential methylation in these genes, or at any other loci at the epigenome-wide significance level (P < 10−7). However, there were 521 sites differentially methylated at P < 0.001 which were enriched for genes involved in neuronal signalling (glutamatergic synapse and long-term potentiation) and cardiomyopathy. Further, the most differentially methylated loci were associated with genes with reported roles in brain function (e.g. TMEM190, MUC3L, CDC20 and SP9). We conclude that the effects of cannabis use on the mature human blood methylome differ from, and are less pronounced than, the effects of tobacco use, and that larger sample sizes are required to investigate this further.

Subject terms: Psychiatric disorders, Genomics, Genetics

Introduction

Cannabis use is an important global public health issue, and a growing topic of controversy and debate1,2. It is the most widely used illicit psychoactive substance in the world3, and the potential medicinal and therapeutic benefits of cannabis and its main active ingredients tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) are gaining interest4–6. There is strong evidence to suggest that the heavy and prolonged use of cannabis may be associated with increased risk of adverse outcomes in a number of areas, including mental health (psychosis7–9, schizophrenia10,11, depression12,13) and illicit drug abuse14.

Drug metabolism, drug response and drug addiction have known genetic components15, and multiple genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified genes and allelic variants that are likely contributors to substance use disorders16,17. There are aspects of cannabis use disorder that are heritable18–21, and several candidate loci for complex phenotypes such as lifetime cannabis use have recently been identified3,22 that explain a proportion of the variance in cannabis use heritability. Complex phenotypes like these are influenced by multiple loci, each of which usually has a small individual effect size23, and such loci are frequently located in non-coding regions of the genome24,25, making their biological role difficult to elucidate.

Epigenetic mechanisms are involved in the interaction between the genome and environment; they respond to changes in environmental stimuli (such as diet, exercise, drugs), and act to alter chromatin structure and thus regulate gene expression26. Epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation, contribute to complex traits and diseases27,28. Methylation of cytosine residues within CpG dinucleotides is an important mechanism of variation and regulation in the genome29–32. Cytosine methylation, particularly in the promoter region of genes, is often associated with a decrease in transcription33, and DNA methylation in the first intron and gene expression is correlated and conserved across tissues and vertebrate species34. Furthermore, modulation of methylation at CpG sites within the human genome can result in an epigenetic pattern that is specific to individual environmental exposures, and these may contribute to disease26,35–37. For example, environmental factors such as drugs, alcohol, stress, nutrition, bacterial infection, and exercise36,38–41 have been associated with methylation changes. A number of these methylation changes have been shown to endure and induce lasting biological changes36, whereas others are dynamic and transient. For example, alcohol consumption affects genome-wide methylation patterns in a severity-dependent manner42 and some of these changes revert upon abstinence from alcohol consumption43. A similar observation is reported for former tobacco smokers, with DNA methylation changes after cessation eventually reaching levels close to those who had never smoked tobacco44. Thus, DNA methylation can be indicative of a particular environmental exposure, shed light on the dynamic interaction between the environment and the genome, and provide new insights in to the biological response.

Recreational drug use (an environmental stimulus) has been associated with adverse mental health outcomes, particularly in youth45–49, and epigenetics may play a role in mediating the biology involved. Therefore, we sought to determine whether regular cannabis users displayed differential cytosine methylation compared with non-cannabis users. Cannabis users in this study are participants from the Christchurch Health and Development Study (CHDS), a longitudinal study of a birth cohort of 1265 children born in 1977 in Christchurch, New Zealand. Users often consume cannabis in combination with tobacco. Unusually, the CHDS cohort contains a subset of cannabis users who have never consumed tobacco, thus enabling an investigation of the specific effects of cannabis consumption, in isolation, on DNA methylation in the human genome.

Methods

Cohort and study design

The Christchurch Health and Development Study includes individuals who have been studied on 24 occasions from birth to the age of 40 (n = 987 at age 30, with blood collected at approximately age 28). In the early 1990s, research began into the initiation and consequences of cannabis use amongst CHDS participants; cannabis use was assessed prospectively over the period up to the collection of DNA11–14,48–54. A subset of n = 96 participants for whom a blood sample was available are included in the current study. Cases (regular cannabis users, n = 48) were matched with controls (n = 48) for sex (n = 37 male, n = 11 female each group, for additional information see Supplementary Table 1). Case participants were partitioned into two subsets: one that contained cannabis-only users (who had never consumed tobacco, “cannabis-only”, n = 24 [n = 21 male, n = 3 female]), and one that contained cannabis users who also consumed tobacco (“cannabis with tobacco”, n = 24 [n = 16 male, n = 8 female]) and were selected on the basis that they either met DSM-IV55 diagnostic criteria for cannabis dependence, or had reported using cannabis on a daily basis for a minimum of three years, prior to age 28. Of the 48 cannabis users, 6 participants had ceased cannabis use by 28 years of age, however, still met the diagnostic criteria for cannabis dependence. Mode of cannabis consumption was via smoking, for all participants. The median duration of regular use was 9 years (range 3–14 years). Control participants had never used cannabis or tobacco. In addition, comprehensive single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data was available for all participants56. All aspects of the study were approved by the Southern Health and Disability Ethics Committee, under application number CTB/04/11/234/AM10 “Collection of DNA in the Christchurch Health and Development Study”, and the CHDS ethics approval covering collection of cannabis use: “16/STH/188/AM03 The Christchurch Health and Development Study 40 Year Follow-up”.

DNA extraction and methylation arrays

DNA was extracted from whole blood using the KingFisher Flex System (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), as per the published protocols. DNA was quantified via NanoDropTM (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and standardised to 100 ng/μl. Equimolar amounts were shipped to the Australian Genomics Research Facility (AGRF, Melbourne, VIC, Australia) for analysis with the Infinium® MethylationEPIC BeadChip (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

Bioinformatics and statistics

All analysis was carried out using R (Version 3.5.257). Prior to normalisation, quality control was performed on the raw data. Firstly, sex chromosomes and 150 failed probes (detection P value > 0.01 in at least 50% of samples) were excluded from analysis. Furthermore, potentially problematic CpGs with adjacent SNVs, or that did not map to a unique location in the genome58, were also excluded, leaving 700,296 CpG sites for further analysis. The raw data were then normalised with the NOOB procedure in the minfi package59 (Supplementary Fig. 1). Normalisation was checked by visual inspection of intensity densities and the first two components from Multi-Dimensional Scaling of the 5000 most variable CpG sites (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). The proportions of cell types (CD4+, CD8+ T cells, natural killer, B cells, monocytes and granulocytes) in each sample were estimated with the Flow.Sorted.Blood package60. Linear models were fitted to the methylated/unmethylated or M ratios using limma61. Separate models were fitted for cannabis-only vs. controls, and cannabis plus tobacco users vs. controls. Both models contained covariates for sex (bivariate), socioeconomic status (three levels), batch (bivariate), population stratification (four principal components from 5000 most variable SNPs) and cell type (five continuous). β values were calculated, defined as the ratio of the methylated probe intensity (M)/the sum of the overall intensity of both the unmethylated probe (U) + methylated probe (M). P values were adjusted for multiple testing with the Benjamini and Hochberg method and assessed for genomic inflation with bacon62. Differentially methylated CpG sites that were intergenic were matched to the nearest neighbouring genes in Hg19 using GRanges63, and the official gene symbols of all significantly differentially methylated CpG sites (nominal P < 0.001) in cannabis-only users were tested for enrichment in KEGG 2019 human pathways with EnrichR64.

Results

Data normalisation

Modelled effects showed no indication of genomic inflation with λ = 1.04 for cannabis-only users (Supplementary Fig. 4a) and λ = 0.855 for cannabis with tobacco users (Supplementary Fig. 4b), versus controls. These were confirmed with bacon for cannabis-only (inflation = 0.98, bias = 0.044) and cannabis with tobacco users (inflation = 0.91, bias = 0.19). Inflation values <1 suggest that the results may be conservative.

Cannabis with tobacco users had a significantly lower estimated proportion of natural killer cells than controls (1.8%, 0.4–3.2%, P < 0.014) with no other proportions differing significantly. After adjusting for multiple comparisons this was not significant (P = 0.08), however, we note that it is consistent with other findings that NK-cells are suppressed in the plasma of tobacco smokers65,66.

Differential methylation

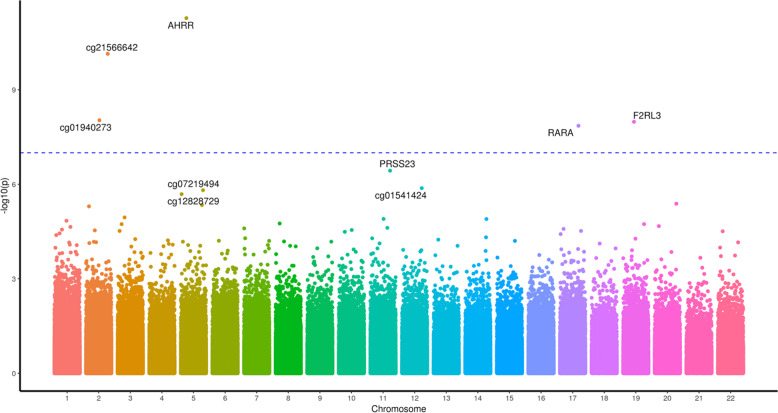

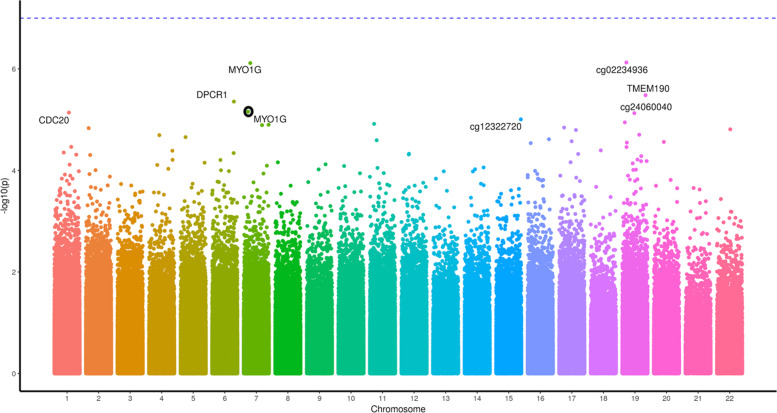

The most differentially methylated CpG sites for cannabis users relative to controls differed in the absence (Table 1) and presence (Table 2) of tobacco smoking. Five individual CpG sites were significantly differentially methylated (P adjusted <0.008) between cannabis users and controls when cannabis with tobacco was used (Table 2 and Fig. 1). The top CpG sites in the AHRR, ALPG and F2RL3 genes (Table 2) are consistent with previous studies on tobacco use without cannabis (e.g. refs. 44,67–69), and cg17739917 is in the same CpG-island as other CpGs previously shown to be hypomethylated in response to tobacco70. Cannabis-only users showed no CpG sites differentially methylated after correction for multiple testing (Table 1 and Fig. 2), however, the most differentially methylated site was hypermethylation of cg12803068 in the gene MYO1G, which has been reported to be hypermethylated in response to tobacco use67. We identified 28 genes with multiple (two or more) differentially methylated CpG probes (Supplementary Table 2). Of these 28 genes, 25 have all sites hypermethylated, one has two sites hypomethylated, two have one hypermethylated and one hypomethylated probe.

Table 1.

Top 15 differentially methylated CpG sites in cannabis-only users vs controls.

| CpG | Gene | Location | Distance | Cannabis | Control | Difference | P value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (bp) | βU | βC | βU − βC | Nominal | Adjusted | |||

| cg12803068 | MYO1G | Intron | 0.8 | 0.71 | 0.1 | 6.30E−07 | 0.4 | |

| cg02234936 | ARHGEF1 | Intron | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 1.10E−06 | 0.4 | |

| cg01695406 | TMEM190 | Intron | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.05 | 3.00E−06 | 0.6 | |

| cg24875484 | MUCL3 | Intron | 0.1 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 3.90E−06 | 0.6 | |

| cg05009104 | MYO1G | Intron | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.05 | 5.90E−06 | 0.6 | |

| cg00470351 | CDC20 | Exon | 0.4 | 0.38 | 0.02 | 6.10E−06 | 0.6 | |

| cg24060040 | DUS3L | Upstream | 11,018 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 6.30E−06 | 0.6 |

| cg12322720 | FOXB1 | Downstream | 150,921 | 0.58 | 0.52 | 0.06 | 8.90E−06 | 0.7 |

| cg16746471 | KIAA1324L | Promoter | 374 | 0.1 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 1.10E−05 | 0.7 |

| cg04180046 | MYO1G | Intron | 0.56 | 0.52 | 0.04 | 1.20E−05 | 0.7 | |

| cg06955687 | DDX25 | Downstream | 28,769 | 0.74 | 0.7 | 0.04 | 1.20E−05 | 0.7 |

| ch.22.707049R | TNRC6B | Downstream | 159,737 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 1.30E−05 | 0.7 |

| cg09344183 | SP9 | Downstream | 5964 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 1.40E−05 | 0.7 |

| cg06693983 | TMEM190 | Exon | 0.84 | 0.76 | 0.08 | 1.40E−05 | 0.7 | |

| cg26069230 | ADAP2 | Exon | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 1.50E−05 | 0.7 |

Beta values with P values, nominal and adjusted by the Benjamini and Hochberg method. Locations are relative to hg19 with gene names for overlapping genes or nearest 5ʹ gene with distance to the 5ʹ end shown.

Table 2.

Top 15 differentially methylated CpG sites in cannabis with tobacco users vs controls.

| CpG | Gene | Location | Distance | Cannabis | Control | Difference | P value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (bp) | βU | βC | βU − βC | Nominal | Adjusted | |||

| cg05575921 | AHRR | Intron | 0.66 | 0.89 | −0.24 | 1.40E−11 | 0.00001 | |

| cg21566642 | ALPG | Downstream | 13,109 | 0.44 | 0.62 | −0.17 | 9.90E−11 | 0.00003 |

| cg03636183 | F2RL3 | Exon | 0.59 | 0.68 | −0.09 | 2.60E−09 | 0.0006 | |

| cg01940273 | ALPG | Downstream | 13,382 | 0.53 | 0.63 | −0.09 | 3.60E−08 | 0.00636 |

| cg17739917 | RARA | Intron | 0.37 | 0.47 | −0.1 | 5.60E−08 | 0.00783 | |

| cg01541424 | LINC02393 | Upstream | 491,508 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 6.30E−07 | 0.07 |

| cg12828729 | TIFAB | Upstream | 35,880 | 0.56 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 7.10E−07 | 0.07 |

| cg10148067 | MTFR1 | Upstream | 3928 | 0.91 | 0.88 | 0.02 | 7.70E−07 | 0.07 |

| cg14391737 | PRSS23 | Intron | 0.36 | 0.42 | −0.06 | 9.60E−07 | 0.07 | |

| cg07219494 | TENM2 | Upstream | 303,359 | 0.7 | 0.75 | −0.05 | 1.40E−06 | 0.1 |

| cg05723029 | PIEZO2 | Intron | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.05 | 1.50E−06 | 0.1 | |

| cg03329539 | ALPG | Downstream | 11,777 | 0.36 | 0.41 | −0.05 | 3.20E−06 | 0.2 |

| cg24994593 | LDLRAD3 | Intron | 0.9 | 0.89 | 0.02 | 4.20E−06 | 0.2 | |

| cg25009999 | LINC01168 | Downstream | 14,152 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.01 | 5.60E−06 | 0.3 |

| cg13957017 | TTLL6 | Intron | 0.72 | 0.69 | 0.03 | 7.30E−06 | 0.3 |

Beta values with P values, nominal and adjusted by the Benjamini and Hochberg method. Locations are relative to hg19 with gene names for overlapping genes or nearest 5ʹ gene with distance to the 5ʹ end shown.

Fig. 1. A Manhattan plot of the genome-wide CpG sites found in the cannabis with tobacco analysis.

The Y axis presents −log10(p) values with the most significantly differentially methylated sites labelled with the gene the CpG site resides in.

Fig. 2. A Manhattan plot of the genome-wide CpG sites found in the cannabis-only analysis.

The Y axis presents −log10(p) values with the most nominally significantly differentially methylated sites labelled with the gene the CpG site resides in. NB, where a gene name is near multiple points, the appropriate point is circled in black.

To describe the data we chose a nominal P value of 0.001, and observed that both cannabis-only and cannabis with tobacco users showed relatively higher rates of hypermethylation than hypomethylation compared with controls and that the distribution of these CpG sites was similar with respect to annotated genomic features (Table 3). Four CpG sites overlapped between the cannabis-only and cannabis with tobacco users analyses; two were hypermethylated; cg02514528, in the promoter of MARC2, and cg27405731 in CUX1, and one, cg26542660 in the promoter of CEP135, was hypomethylated in comparison to controls. The second most differentially methylated site (ranked by P value) in cannabis-only users was cg02234936 which maps to ARHGEF1; this was hypermethylated in the cannabis with tobacco users.

Table 3.

Summary of CpG sites from cannabis-only and cannabis with tobacco users vs. non-users.

| Cannabis-only | Tobacco + Cannabis | Both | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differentially methylated loci (FWER = 0.05) | 0 | 6 | |||

| Differentially methylated loci (P < 0.001) | |||||

| Total | 521 | 533 | |||

| Hypermethylated | 420 | 80.6% | 403 | 75.6% | 2 |

| Hypomethylated | 101 | 19.4% | 130 | 24.4% | 1 |

| Hyper (cannabis) Hypo (cannabis + tobacco) | 1 | ||||

| Location | |||||

| Intron | 216 | 41.5% | 264 | 49.5% | |

| Exon | 97 | 18.6% | 65 | 12.2% | |

| Exon Boundary | 0 | 0 | |||

| Promoter | 89 | 17.1% | 60 | 11.3% | |

| 3ʹ UTR | 3 | 0.6% | 1 | 0.2% | |

| 5ʹ UTR | 0 | 0 | |||

| 3ʹ (downstream) | 62 | 11.9% | 76 | 14.3% | |

| 5ʹ (upstream) | 54 | 10.4% | 67 | 12.6% |

Counts of significant sites at P = 0.001 and at a Benjamini and Hochberg adjusted P < 0.05. ‘Both’ indicates the number of CpG sites of each type that are present and shared across both analyses.

FWER family-wise error rate.

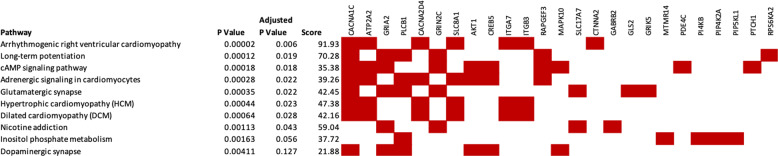

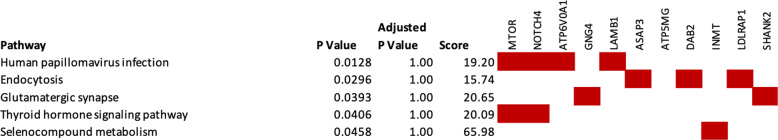

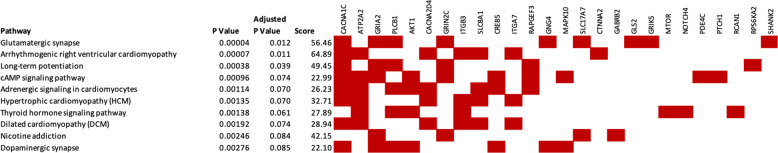

Pathway enrichment analyses

We then took the genes containing differentially methylated CpG sites at P < 0.001 for the cannabis-only group, or the closest gene where that CpG was intergenic (Supplementary Table 3) and compared them with human KEGG pathways using Enrichr. The hypermethylated CpG sites (n = 420) showed enrichment in the arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, long-term potentiation, cAMP signalling, adrenergic signalling in cardiomyocytes, glutamatergic synapse, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, dilated cardiomyopathy and nicotine addiction pathways at an adjusted P < 0.05 (Fig. 3). Enrichment analysis of hypomethylated loci (n = 101) in cannabis-only users did not identify any KEGG pathways at or near adjusted significance (P > 0.05, Fig. 4). We further submitted all differentially methylated CpG sites (hyper and hypomethyated) at a nominal P < 0.001 to Enrichr, revealing significant enrichment for genes involved in the glutamatergic synapse (adjusted P = 0.012), arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (adjusted P = 0.011) and long-term potentiation pathways (adjusted P = 0.039) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3. Genetic networks enriched within the hypermethylated CpG sites identified in the cannabis-only analysis.

Pathways from KEGG 2019. Genes shown by filled cells are hypermethylated in cannabis-only users and included in named pathway.

Fig. 4. Genetic networks enriched within the hypomethylated CpG sites identified in the cannabis-only users.

Pathways from KEGG 2019. Genes shown by filled cells are hypomethylated in cannabis-only users and included in named pathway.

Fig. 5. Genetic networks enriched within the hypomethylated or hypermethylated CpG sites identified in the cannabis-only users.

Pathways from KEGG 2019. Genes shown by filled cells are hypomethylated in cannabis-only users and included in named pathway.

Discussion

Many countries have recently adopted, or are considering, lenient polices regarding the personal use of cannabis71–73. This approach is supported by the evidence that the prohibition of cannabis can be harmful53. Further, the therapeutic benefits of cannabis are gaining traction, most recently as an opioid replacement therapy74. However, previous studies, including analyses of the CHDS cohort, have reported an association between cannabis use and poor health outcomes, particularly in youth75,76. Epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation, provide the interface between the environment (e.g. cannabis exposure) and genome. Therefore, we investigated whether changes in an epigenetic mark, DNA methylation, were altered in cannabis users, versus controls, a comparison made possible by the deep phenotyping of the CHDS cohort with respect to cannabis use, and the fact that the widespread practice of mulling or mixing cannabis with tobacco, is not common in New Zealand.

Consistent with previous reports of tobacco exposure, we observed greatest differential methylation in cannabis with tobacco users in the AHRR and F2RL3 genes44,67–69. These changes, however, were not apparent in the cannabis-only data. Only two nominally significantly differentially methylated (P < 0.05) CpG sites were observed in both the cannabis-only and cannabis with tobacco analyses. This suggests that tobacco may have a more pronounced effect on DNA methylation and/or dominates any effects of cannabis on the human blood methylome, and that caution should be taken when interpreting similar cannabis exposure studies which do not, or cannot, exclude tobacco smokers. Interestingly, the two nominally significant CpG sites (P < 0.05) that overlap between the cannabis-only and the cannabis with tobacco data are located within the MARC2 and CUX1 genes, which both have reported roles in brain function; a SNP in MARC2 has been provisionally associated with the biological response to antipsychotic therapy in schizophrenia patients77, and the CUX1 gene has an established role in neural development78.

Cannabis affects the brain, leading to perceptual alterations, euphoria and relaxation18, and prolonged use is associated with mood disorders, including adult psychosis7,8,49,79,80, mania13, and depression12. We did not detect significantly differentially methylated loci associated with exclusive cannabis use at the epigenome-wide level. However, an assessment of those top loci reaching nominal significance (P < 0.05) identified CpG sites within genes involved in brain function and mood disorders, including MUC3L81,82, CDC2083, DUS3L84, TMEM19085, FOXB186–88, KIAA1324L/GRM382,89–94, DDX2581,95,96, TNRC6B97,98 and SP999.

Pathway enrichment revealed that differential methylation in cannabis-only users was over-represented in genes associated with neural signalling and cardiomyopathies. This is consistent with the literature which raises clinical concerns around cardiac complications potentially associated with cannabis use100–103. The enrichment of genes associated with neural signalling pathways is also consistent with the literature, including previous analyses of the CHDS cohort, which report associations between cannabis exposure and brain related biology such as mood disorders7,12,48,49,51–54,104,105. Our study was limited by sample size, achieving ~10% power at P = 10−7 to detect the largest standardised effect size found. However, while we have not implicated any gene at the genome-wide significance level with respect to differential methylation associated with cannabis-only exposure, our data are suggestive of a role for DNA methylation in the biological response to cannabis, a possibility which definitely warrants further investigations in larger cohorts.

In summary, while tobacco use has declined on the back of state-sponsored cessation programmes106, rates of cannabis use remain high in New Zealand and globally, and might be predicted to increase further with the decriminalisation or legalisation of cannabis use for therapeutic and/or recreational purposes107. Therefore, analysis of the potential effects of cannabis (an environmental stimuli) on DNA methylation, an epigenetic mechanism, is timely. Our data are suggestive of a role for DNA methylation in the biological response to cannabis, significantly contributes to the growing literature studying the biological effects of heavy cannabis use, and highlights areas of further analysis in particular with respect to the epigenome.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Allison Miller for technical assistance. CHDS, University of Otago Division of Health Sciences Collaborative Postdoctoral Fellowship to A.J.O., University of Otago Research Grant to M.A.K., The Carney Centre for Pharmacogenomics. CHDS was funded by the Health Research Council of New Zealand (Programme Grant 16/600) and the Canterbury Medical Research Foundation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Amy J. Osborne, John F. Pearson

Contributor Information

Amy J. Osborne, Email: amy.osborne@canterbury.ac.nz

Martin A. Kennedy, Email: martin.kennedy@otago.ac.nz

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41398-020-0800-3).

References

- 1.Cressey D. The cannabis experiment. Nature. 2015;524:280–283. doi: 10.1038/524280a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldman D. America’s cannabis experiment. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:969–970. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stringer S, et al. Genome-wide association study of lifetime cannabis use based on a large meta-analytic sample of 32 330 subjects from the International Cannabis Consortium. Transl. Psychiatry. 2016;6:e769. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robson P. Therapeutic aspects of cannabis and cannabinoids. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2001;178:107–115. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amar MB. Cannabinoids in medicine: a review of their therapeutic potential. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006;105:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whiting PF, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama. 2015;313:2456–2473. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fergusson DM, Poulton R, Smith PF, Boden JM. Cannabis and psychosis. Br. Med. J. 2006;332:172–176.. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7534.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fergusson DM, Hall W, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Rethinking cigarette smoking, cannabis use, and psychosis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:581–582. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00208-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radhakrishnan R, Wilkinson ST, D’Souza DC. Gone to pot—a review of the association between cannabis and psychosis. Front. Psychiatry. 2014;5:54. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Power RA, et al. Genetic predisposition to schizophrenia associated with increased use of cannabis. Mol. Psychiatry. 2014;19:1201. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gage SH, et al. Assessing causality in associations between cannabis use and schizophrenia risk: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Psychological Med. 2017;47:971–980. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716003172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horwood LJ, et al. Cannabis and depression: an integrative data analysis of four Australasian cohorts. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;126:369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibbs M, et al. Cannabis use and mania symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2015;171:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Cannabis use and other illicit drug use: Testing the gateway hypothesis. Addiction. 2006;101:556–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang JC, Kapoor M, Goate AM. The genetics of substance dependence. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. G. 2012;13:241–261. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-090711-163844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adkins DE, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of longitudinal alcohol consumption across youth and early adulthood. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2015;18:335–347. doi: 10.1017/thg.2015.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costello EJ, et al. Genes, environments, and developmental research: methods for a multi-site study of early substance abuse. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2013;16:505–515. doi: 10.1017/thg.2013.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall W, Solowij N. Adverse effects of cannabis. Lancet. 1998;352:1611–1616. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verweij KJ, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on cannabis use initiation and problematic use: a meta-analysis of twin studies. Addiction. 2010;105:417–430. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02831.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gillespie NA, et al. Associations between personality disorders and cannabis use and cannabis use disorder: a population-based twin study. Addiction. 2018;113:1488–1498. doi: 10.1111/add.14209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gillespie NA, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Pathways to cannabis abuse: a multi-stage model from cannabis availability, cannabis initiation and progression to abuse. Addiction. 2009;104:430–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02456.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pasman, J. A. et al. Genome-wide association analysis of lifetime cannabis use (N = 184,765) identifies new risk loci, genetic overlap with mental health, and a causal influence of schizophrenia on cannabis use. bioRxiv 234294 (2018).

- 23.Visscher PM, Brown MA, McCarthy MI, Yang J. Five years of GWAS discovery. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;90:7–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ward LD, Kellis M. Interpreting noncoding genetic variation in complex traits and human disease. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:1095. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fagny M, et al. Exploring regulation in tissues with eQTL networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E7841–E7850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1707375114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaenisch R, Bird A. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: how the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nat. Genet. 2003;33:245–254. doi: 10.1038/ng1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petronis A. Epigenetics as a unifying principle in the aetiology of complex traits and diseases. Nature. 2010;465:721. doi: 10.1038/nature09230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spadafora R. The Key Role of Epigenetics in Human Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018;379:400. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1805989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lister R, et al. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature. 2009;462:315–322. doi: 10.1038/nature08514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee HJ, Hore TA, Reik W. Reprogramming the methylome: erasing memory and creating diversity. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:710–719. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lowdon RF, Jang HS, Wang T. Evolution of epigenetic regulation in vertebrate genomes. Trends Genet. 2016;32:269–283. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lea AJ, et al. Genome-wide quantification of the effects of DNA methylation on human gene regulation. ELife. 2018;7:e37513. doi: 10.7554/eLife.37513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore LD, Le T, Fan G. DNA methylation and its basic function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:23. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anastasiadi D, Esteve-Codina A, Piferrer F. Consistent inverse correlation between DNA methylation of the first intron and gene expression across tissues and species. Epigenet. chromatin. 2018;11:37. doi: 10.1186/s13072-018-0205-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jirtle RL, Skinner MK. Environmental epigenomics and disease susceptibility. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007;8:253–262. doi: 10.1038/nrg2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feil R, Fraga MF. Epigenetics and the environment: emerging patterns and implications. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012;13:97–109. doi: 10.1038/nrg3142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garg P, Joshi RS, Watson C, Sharp AJ. A survey of inter-individual variation in DNA methylation identifies environmentally responsive co-regulated networks of epigenetic variation in the human genome. PLoS Genet. 2018;14:e1007707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dominguez-Salas P, et al. Maternal nutrition at conception modulates DNA methylation of human metastable epialleles. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3746. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barres R, et al. Acute exercise remodels promoter methylation in human skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 2012;15:405–411. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pacis A, et al. Bacterial infection remodels the DNA methylation landscape of human dendritic cells. Genome Res. 2015;25:1801–1811. doi: 10.1101/gr.192005.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rönn T, et al. A six months exercise intervention influences the genome-wide DNA methylation pattern in human adipose tissue. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003572. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Philibert RA, Plume JM, Gibbons FX, Brody GH, Beach SRH. The impact of recent alcohol use on genome wide DNA methylation signatures. Front. Genet. 2012;3:54. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Philibert RA, et al. A pilot examination of the genome-wide DNA methylation signatures of subjects entering and exiting short-term alcohol dependence treatment programs. Epigenetics. 2014;9:1212–1219. doi: 10.4161/epi.32252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zeilinger S, et al. Tobacco smoking leads to extensive genome-wide changes in DNA methylation. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e63812. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Macleod J, et al. Psychological and social sequelae of cannabis and other illicit drug use by young people: a systematic review of longitudinal, general population studies. Lancet. 2004;363:1579–1588. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16200-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGee R, Williams S, Poulton R, Moffitt T. A longitudinal study of cannabis use and mental health from adolescence to early adulthood. Addiction. 2000;95:491–503. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.9544912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moore TH, et al. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2007;370:319–328. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Psychosocial sequelae of cannabis use and implications for policy: findings from the Christchurch Health and Development Study. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2015;50:1317–1326. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fergusson DM, Horwood L, Swain-Campbell N. Cannabis dependence and psychotic symptoms in young people. Psychological Med. 2003;33:15–21. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fergusson DM. Is there a causal linkage between cannabis use and increased risk of psychotic symptoms? (Commentary) Addiction. 2010;105:1336–1337. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Boden JM. Is driving under the influence of cannabis becoming a greater risk to driver safety than drink driving? Findings from a 25-year longitudinal study. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2008;40:1345–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Tests of causal linkages between cannabis use and psychotic symptoms. Addiction. 2005;100:354–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fergusson DM, Swain-Campbell NR, Horwood LJ. Arrests and convictions for cannabis related offences in a New Zealand birth cohort. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70:53–63. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00336-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Horwood LJ, et al. Cannabis use and educational achievement: findings from three Australasian cohort studies. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Association, A. P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth edition (American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, 1994).

- 56.Pearson JF, et al. Increased risk of major depression by childhood abuse is not modified by CNR1 genotype. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2013;2:224. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Team, R. C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (Vienna, Austria, 2019).

- 58.Pidsley R, et al. Critical evaluation of the Illumina MethylationEPIC BeadChip microarray for whole-genome DNA methylation profiling. Genome Biol. 2016;17:208. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1066-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Triche TJ, Jr, Weisenberger DJ, Van Den Berg D, Laird PW, Siegmund KD. Low-level processing of Illumina Infinium DNA methylation beadarrays. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e90–e90. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jaffe, A. E. FlowSorted.Blood.450k: Illumina HumanMethylation Data on Sorted Blood Cell Populations (2019).

- 61.Ritchie ME, et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47–e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Iterson M, van Zwet EW, Heijmans BT, Consortium B. Controlling bias and inflation in epigenome-and transcriptome-wide association studies using the empirical null distribution. Genome Biol. 2017;18:19. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1131-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lawrence M, et al. Software for computing and annotating genomic ranges. PLoS Computational Biol. 2013;9:e1003118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kuleshov MV, et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W90–W97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ferson M, Edwards A, Lind A, Milton G, Hersey P. Low natural killer‐cell activity and immunoglobulin levels associated with smoking in human subjects. Int. J. Cancer. 1979;23:603–609. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910230504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mian MF, Lauzon NM, Stämpfli MR, Mossman KL, Ashkar AA. Impairment of human NK cell cytotoxic activity and cytokine release by cigarette smoke. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008;83:774–784. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0707481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ambatipudi S, et al. Tobacco smoking-associated genome-wide DNA methylation changes in the EPIC study. Epigenomics. 2016;8:599–618. doi: 10.2217/epi-2016-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Breitling LP, Yang RX, Korn B, Burwinkel B, Brenner H. Tobacco-smoking-related differential DNA methylation: 27K discovery and replication. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011;88:450–457. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shenker NS, et al. DNA methylation as a long-term biomarker of exposure to tobacco smoke. Epidemiology. 2013;24:712–716. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31829d5cb3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Joehanes R, et al. Epigenetic signatures of cigarette smoking. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genet. 2016;9:436–447. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.116.001506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kilmer B. Recreational cannabis—minimizing the health risks from legalization. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;376:705–707. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1614783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cerdá M, Kilmer B. Uruguay’s middle-ground approach to cannabis legalization. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2017;42:118. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bifulco M, Pisanti S. Medicinal use of cannabis in Europe. EMBO Rep. 2015;16:130–132. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wiese B, Wilson-Poe AR. Emerging evidence for cannabis’ role in opioid use disorder. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2018;3:179–189. doi: 10.1089/can.2018.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hall W. Challenges in minimizing the adverse effects of cannabis use after legalization. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2015;50:1013–1015. doi: 10.1007/s00127-015-1067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Boden JM, Fergusson DM. Cannabis law and cannabis-related harm. N.Z. Med. J. (Online) 2019;132:7–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Åberg K, et al. Genomewide association study of movement-related adverse antipsychotic effects. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;67:279–282. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Platzer K, et al. Haploinsufficiency of CUX1 causes nonsyndromic global developmental delay with possible catch-up development. Ann. Neurol. 2018;84:200–207. doi: 10.1002/ana.25278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Caspi A, et al. Moderation of the effect of adolescent-onset cannabis use on adult psychosis by a functional polymorphism in the catechol-O-methyltransferase gene: longitudinal evidence of a gene X environment interaction. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;57:1117–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Henquet C, Di Forti M, Morrison P, Kuepper R, Murray RM. Gene-environment interplay between cannabis and psychosis. Schizophrenia Bull. 2008;34:1111–1121. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Consortium C-DGotPG. Identification of risk loci with shared effects on five major psychiatric disorders: a genome-wide analysis. Lancet. 2013;381:1371–1379. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62129-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Consortium TASDWGoTPG. Meta-analysis of GWAS of over 16,000 individuals with autism spectrum disorder highlights a novel locus at 10q24. 32 and a significant overlap with schizophrenia. Mol. Autism. 2017;8:1–17. doi: 10.1186/s13229-017-0137-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Winham SJ, et al. Genome-wide association study of bipolar disorder accounting for effect of body mass index identifies a new risk allele in TCF7L2. Mol. Psychiatry. 2014;19:1010. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Linnér RK, et al. Genome-wide association analyses of risk tolerance and risky behaviors in over 1 million individuals identify hundreds of loci and shared genetic influences. Nat. Genet. 2019;51:245. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0309-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wong M-L, et al. The PHF21B gene is associated with major depression and modulates the stress response. Mol. Psychiatry. 2017;22:1015. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Davies G, et al. Study of 300,486 individuals identifies 148 independent genetic loci influencing general cognitive function. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2098. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04362-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cox AJ, et al. Heritability and genetic association analysis of cognition in the Diabetes Heart Study. Neurobiol. Aging. 2014;35:1958. e1953–1958. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lee JJ, et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nat. Genet. 2018;50:1112. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0147-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Goes FS, et al. Genome-wide association study of schizophrenia in Ashkenazi Jews. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part B: Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2015;168:649–659. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ikeda M, et al. Genome-Wide Association Study Detected Novel Susceptibility Genes for Schizophrenia and Shared Trans-Populations/Diseases Genetic Effect. Schizophrenia Bull. 2018;45:824–834. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lam, M. et al. Pleiotropic meta-analysis of cognition, education, and schizophrenia differentiates roles of early neurodevelopmental and adult synaptic pathways. bioRxiv, 519967 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 92.Li Z, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies 30 new susceptibility loci for schizophrenia. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:1576. doi: 10.1038/ng.3973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Periyasamy S, et al. Association of schizophrenia risk with disordered niacin metabolism in an Indian genome-wide association study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:1026–1034. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ripke S, et al. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511:421. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Herold C, et al. Family-based association analyses of imputed genotypes reveal genome-wide significant association of Alzheimer’s disease with OSBPL6, PTPRG, and PDCL3. Mol. Psychiatry. 2016;21:1608. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ripke S, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies five new schizophrenia loci. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:969. doi: 10.1038/ng.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Karpova A, Sanna P, Behnisch T. Involvement of multiple phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent pathways in the persistence of late-phase long term potentiation expression. Neuroscience. 2006;137:833–841. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sui L, Wang J, Li B-M. Role of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase-Akt-mammalian target of the rapamycin signaling pathway in long-term potentiation and trace fear conditioning memory in rat medial prefrontal cortex. Learn. Mem. 2008;15:762–776. doi: 10.1101/lm.1067808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kichaev G, et al. Leveraging polygenic functional enrichment to improve GWAS power. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2019;104:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Singh A, et al. Cardiovascular complications of marijuana and related substances: a review. Cardiol. Ther. 2018;7:45–59. doi: 10.1007/s40119-017-0102-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rezkalla S, Kloner RA. Cardiovascular effects of marijuana. Trends Cardiovas. Med. 2018;29:403–407. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Jones RT. Cardiovascular system effects of marijuana. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002;42:58S–63S. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.2002.tb06004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Goyal H, Awad HH, Ghali JK. Role of cannabis in cardiovascular disorders. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017;9:2079. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.06.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Soto D, Altafaj X, Sindreu C, Bayés À. Glutamate receptor mutations in psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders. Communicative Integr. Biol. 2014;7:e27887. doi: 10.4161/cib.27887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Billingsley KJ, et al. Regulatory characterisation of the schizophrenia-associated CACNA1C proximal promoter and the potential role for the transcription factor EZH2 in schizophrenia aetiology. Schizophrenia Res. 2018;199:168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ministry of Health. Annual Update of Key Results 2017/18: New Zealand Health Survey (ed. M.o. Health) (Ministry of Health, Wellington, 2018).

- 107.World Health Organization. The Health and Social Effects of Nonmedical Cannabis Use (World Health Organization, 2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.