Abstract

Protein post-translational modifications (PTMs) have emerged to be combinatorial, essential mechanisms used by eukaryotic cells to regulate local chromatin structure, diversify and extend their protein functions and dynamically coordinate complex intracellular signalling processes. Most common types of PTMs include enzymatic addition of small chemical groups resulting in phosphorylation, glycosylation, poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation, nitrosylation, methylation, acetylation or covalent attachment of complete proteins such as ubiquitin and SUMO. Protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) and protein lysine methyltransferases (PKMTs) enzymes catalyse the methylation of arginine and lysine residues in target proteins, respectively. Rapid progress in quantitative proteomic analysis and functional assays have not only documented the methylation of histone proteins post-translationally but also identified their occurrence in non-histone proteins which dynamically regulate a plethora of cellular functions including DNA damage response and repair. Emerging advances have now revealed the role of both histone and non-histone methylations in the regulating the DNA damage response (DDR) proteins, thereby modulating the DNA repair pathways both in proliferating and post-mitotic neuronal cells. Defects in many cellular DNA repair processes have been found primarily manifested in neuronal tissues. Moreover, fine tuning of the dynamicity of methylation of non-histone proteins as well as the perturbations in this dynamic methylation processes have recently been implicated in neuronal genomic stability maintenance. Considering the impact of methylation on chromatin associated pathways, in this review we attempt to link the evidences in non-histone protein methylation and DDR with neurodegenerative research.

Keywords: DNA damage response, DNA repair, Non-histone protein methylation, Lysine methylation, Arginine methylation, Neurodegenerative diseases

Introduction

The precision and accuracy in the intracellular process of the repair of damaged nuclear and mitochondrial DNA is critical in maintaining the genomic integrity aiding in the survival of all organisms. Any irregularity in maintenance of genome stability and pathways ensuring it, result in a spectrum of human disorders with developmental defects, neurodegeneration, immune deficiency, premature aging, or cancer. The association between increase in DNA damage and decreased repair efficiency with neurodegenerative disease and premature aging has been well documented in literature (Borgesius et al. 2011; Hegde et al. 2017). In response to various endogenous and exogenous DNA damage, cells rapidly activate DNA damage response (DDR) mechanisms to channel the lesions into specific DNA repair pathways and further coordinate with cell cycle progression and apoptosis (Ciccia and Elledge 2010; Polo and Jackson 2011). Current status of the DDR molecular mechanisms has been extensively reviewed in many of the literature precedence (Branzei and Foiani 2008; Jackson and Bartek 2009; Raschella et al. 2017). The DNA damage-induced post translational modifications (PTMs) of chromatin associated histones and non-histone proteins are critical components of DDR machinery and proven to be significant to facilitate the accurate repair of the damaged DNA strand (Lukas et al. 2011; Gong and Miller 2019). Predominant PTMs being displayed by proteins under DNA damaging conditions include Phosphorylation, Ubiquitylation, SUMOylation, Acetylation, Methylation, and PARylation (Polo and Jackson 2011; Dabin et al. 2016). The intricate control of chromatin modifications that modulate DDR are available in the recent reviews (Polo and Almouzni 2015; Dabin et al. 2016; Gong and Miller 2019; Kim et al. 2019).

Progressive neuronal cell loss is a pathological hallmark of many neurodegenerative disorders including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), Huntington’s disease (HD) and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). Although most neurodegenerative diseases are heterogeneous, genetic mutations resulting in defective DNA repair, mitochondrial dysfunction, and metabolic stress act in tandem with environmental factors and ageing to contribute to the pathogenesis. Neurons are very sensitive to DNA damage due to high oxidative metabolism and the lower capacity to neutralize reactive oxygen species. Since the oxygen consumption of brain is high (about 20% of total oxygen consumed), rapid change in the chromatin architecture has a vital role to play in DDR to encounter the persistent oxidative damage to the neuronal genome (Hegde et al. 2017). The free radicals generated as a result of high oxidative load and cellular metabolism in the brain can cause many different types of DNA damage including deleterious DNA breaks and protein-DNA cross links that can block the active transcription and induce genomic instability and neuronal cell death (McKinnon 2009).

Methylation of lysine and arginine residues in proteins play key roles in modulating cellular response to DNA damage (Gong and Miller 2019). Multiple lines of evidence indicate that proteins involved in both the arms of cellular response to DNA damage, DNA repair and cell death pathways, undergoes extensive and dynamic methylation (Peng and Wong 2017; Zhang et al. 2018). In general, many methyltransferase enzymes modify both histone and non-histone proteins, and often in DDR, both these modifications cross talk in a well-coordinated manner to regulate DNA damage signalling cascades. While it was demonstrated that the fine balance of dynamic methylation of histone proteins effectively modulates the chromatin dynamics during DDR, emerging data imply that methylation of non-histone proteins could also have penetrating implications in neuronal DDR and pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disease. The consequence of defective methylation in DDR are just beginning to be understood in proliferating cells, mostly in the context of cancer, while their roles in modulating DDR in neuronal cells still remaining ambiguous. A lot of futuristic insight is needed to test whether such non-histone methylations perform identical functions in post-mitotic neuronal cells. The current review will focus on the emerging field of non-histone lysine and arginine methylation in regulating DNA damage response and DNA repair in neuronal cells, and their implications in neurodegenerative diseases.

DNA damage response in neuronal cells

DDR is achieved through the simultaneous collaborative actions of multiple checkpoint and repair proteins that detect the damage, remodel the chromatin, coordinating the repair with cell cycle progression, inducing apoptosis, autophagy, or senescence, if the damage is left unrepaired (Harper and Elledge 2007; Soria et al. 2012). Patients with genetic mutations in many DNA repair factors show common symptoms of neurodevelopmental abnormalities, in addition to cancer predisposition, suggesting important roles of these factors in neuronal genomic stability maintenance during both neurodevelopment and in the maturation of neuronal cells (Hegde et al. 2017). Specialized DDR and repair pathways are activated in response to different kinds of lesions, their locations in genome and the cell cycle phase at which such lesions appear. Consistent with this, the DNA repair mechanisms in the neuronal progenitor cells and mature neurons differ owing to the difference in their DNA replication, cell division, homologous recombination repair, and apoptotic status (McKinnon 2013). Therefore, because of their longer life span, mature neuronal cells with defective DNA repair machinery appears to be more susceptible to cell death as a consequence of endogenous DNA damage. Additionally, DNA damage may also be a by-product of glutamate receptor activation as evidenced by the presence of γH2AX, a marker associated with DNA damage and repair (Crowe et al. 2006). Recently, defects in RNA-DNA hybrid (R-loop) processing machinery and RNA processing factros has also been inplicated in the progression of a number of neurodegenerative diseases (Loomis et al. 2014; Lim et al. 2015). In the subsequent sub-sections, the neurodegenerative diseases resulting from the mutations in various DNA repair factors will be discussed.

Double strand break repair and neurodegenerative diseases

Although DNA double strand breaks (DSB) can be repaired by accurate homologous recombination (HR) pathways, non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway operates in the mature nervous system (Lieber et al. 2003). Mutations in the NHEJ factor, Ligase IV, showed developmental and growth delay, and some clinical features similar to the one found in Nijmegen breakage syndrome (NBS). These mutations either affect the enzymatic activity or interactions XRCC4 with other repair factors (O’Driscoll et al. 2001). Severely impaired neurological functions were observed in patients with mutant DNA-PKc (Woodbine et al. 2013). Neurodegeneration is a major clinical feature in ataxia-telangiectasia (A-T) where the DNA double strand break signalling serine/threonine kinase, Ataxia-Telangiectasia Mutated gene (ATM), is mutated (Savitsky et al. 1995). Mutations in the DNA damage signalling MRN complex (MRE11/RAD50/NBS1) lead to genomic instability disorders: Nijmegen breakage syndrome (NBS), and ataxia-telangiectasia like disease (ATLD) with prominent clinical features of microcephaly (Carney et al. 1998; Varon et al. 1998; Stewart et al. 1999). The single strand break and replication stress sensor kinase, ATR (Ataxia Telangiectasia and Rad3-related) associated mutations lead to Seckel syndrome (O’Driscoll et al. 2003). It was reported that ATM recruits huntingtin protein to the site of DNA damage where it acts as a scaffold protein for the repair of oxidative stress induced damage (Maiuri et al. 2017). Consistent with this, Huntington’s Disease (HD) patients show defective repair, chromatin modification and DNA methylation patterns (Horvath et al. 2016).

Base excision repair and single strand break repair in neurodegenerative diseases

Damage to only one DNA strand leading to single-strand breaks (SSB), is also a common DNA lesion occuring due to the direct effects of ROS or indirectly as an intermediate during DNA base excision repair (BER) (Poletto et al. 2017). A series of neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental disorders has been identified in BER and single strand break repair protein defects. Mutations in tyrosyl DNA-phosphodiesterase 1 (TDP1), aprataxin (APTX) and polynucleotide kinase/phosphatase (PNKP) results in Spinocerebellar Ataxia with Axonal Neuropathy (SCAN1), Ataxia-Ocular motor apraxia 1 (AOA1), and Microcephaly with Seizures (MCSZ) or Ataxia-ocular motor Apraxia 4 (AOA4), respectively (Bras et al. 2015; Ceccaldi et al. 2016; Date et al. 2001; Hoch et al. 2017; Moreira et al. 2001; Takashima et al. 2002). Mutations in XRCC1, a scaffold protein involved in SSB repair, were reported in cerebellar ataxia too (Hoch et al. 2017).

Necleotide excision repair and neurodegenerative diseases

Both global genome nucleotide excision repair (GG-NER) and transcription coupled NER (TC-NER) are active in brain as the mutations in the proteins involved in these pathways leads to various neurodevelopmental manifestations (McKinnon 2013). Mutations in GG-NER factors are implicated in human syndrome Xeroderma pigmentosum (XP). Defective TC-NER machinery results in Trichothiodystrophy (TTD), Cockayne Syndrome (CS), and infantile lethal cerebro-oculo-facio-skeletal syndrome (Kraemer et al. 2007; Laugel et al. 2010; McKinnon 2013; Hashimoto et al. 2016).

Mutations in RNA processing factors and neurodegenerative diseases

Aicardi-Goutières syndrome (AGS) results from mutations in genes encoding proteins TREX 1 (AGS1), RNase H2 (AGS2, 3 and 4) and SAMHD1 (AGS5). The mis-incorporated ribonucleotide triphosphates (rNTPs) into DNA are removed by rNTP excision repair proteins, TREX1 and RNase H2. Mutations in these genes in AGS cells results in increased RNA:DNA hybrid (R-loops) and epigenetic changes including decreased DNA methylation (Lim et al. 2015).

Mitochondrial DNA repair and neurodegenerative diseases

Damage to mitochondrial genome is also common, as it is the major site for ROS generation and dysfunctional mitochondria have been identified as a major cause of neurodegeneration (de Souza-Pinto et al. 2008). Active DNA repair mechanisms are required to safeguard mitochondrial DNA. Most of the nuclear DNA repair mechanisms exist in mitochondria due to the import of repair enzymes to mitochondria (Zinovkina 2018). Increasing evidences suggest that aberrant processing of mitochondrial DNA damage is indeed an important causal factor in many human diseases. Interestingly, a link between reactive oxygen species (ROS) mediated mitochondrial damage was implicated in aging and in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disease such as PD (Zinovkina 2018). Adding on, mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) can lead to mitochondrial dysfunction and cell death as seen in cases of AD and PD (de Souza-Pinto et al. 2008; Bender et al. 2006). Hence, it is also important in the future to address the mitochondrial dysfunction that leads to neuropathology of human syndromes resulting from DNA repair defects.

Now it is clear that most proteins involved in DDR and repair are regulated by multiple PTMs and their complex cross talk with each other (Dantuma and van Attikum 2016). Therefore, in addition to the presence of intact DNA repair proteins, the appropriate repair of damaged DNA also requires multiple PTMs including methylation (Jackson and Durocher 2013; Brinkmann et al. 2015; Polo and Almouzni 2015; Dantuma and van Attikum 2016; Dhar et al. 2017). Consistent with this, defect in the PTMs pathways could contribute to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases similar to the one observed in the respective DNA repair gene mutation. In this context, we will highlight the current understanding of the roles played by both arginine and lysine methylation in neuronal genome stability maintenance in the next sections.

Protein methylation and DNA damage response

The histone and non-histone protein methylations together play important roles in maintaining the genomic stability by persuading the DDR pathway choice and repair. Protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) and protein lysine methyltransferases (PKMTs) are responsible for the methylation of arginine and lysine residues in target proteins, respectively. Although many of the methylation sites in non-histone proteins were identified by proteomic approaches, future studies are necessary to determine their precise roles in DNA damage response and downstream signalling. Here we will highlight various arginine and lysine methylated DDR and cell cycle factors and their possible implications in neurodegenerative disorders.

Arginine methylation

Arginine methylation is a ubiquitous PTM and about 1% of arginine in proteins is found getting methylated (Bulau et al. 2006). Furthermore, immunoaffinity purification coupled with mass spectrometry identified monomethylated arginine in more than 3000 proteins (Guo et al. 2014; Larsen et al. 2016). As arginine residue is an important regulator of DNA-protein and protein-protein interactions, methylation can greatly influence DNA damage response and repair. The nine Protein Arginine Methyltransferase (PRMT) found in mammalian cells are further classified into three sub-types. Type I PRMTs (PRMT1–4, PRMT6, and PRMT8) produce asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA/ Rme2a). Type II PRMTs (PRMT5 and PRMT9) catalyse the formation of symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA/Rme2s). The only member in Type III (PRMT7), class catalyse the monomethylation (MMA/Rme1) reaction (Morales et al. 2016; Lorton and Shechter 2019). The most common amino acid sequences where arginine is methylated is the Glycine-and-arginine-rich (GAR/RGG) motifs. Methylation was also observed in motifs in which two arginine residues separated by another amino acid (RXR) motif or regions with disordered/low structural complexity (Geoghegan et al. 2015; Nott et al. 2015). The arginine methylation can be reversed by the action of demethylases or protein arginine deiminases (PADs) (Bicker and Thompson 2013). Additionally, few Jumonji domain-containing (JmjC) lysine demethylase enzymes also remove methyl group from arginine residues. However, how the activities of various PRMTs and demethylases are synchronized under different cellular conditions are not understood yet.

Arginine methylation of DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair proteins

DNA double strand processing proteins like 53BP1 (p53 binding protein), MRE11 (Meiotic recombination 11), and BRCA1 (breast cancer susceptibility protein) are dimethylated on arginine residues by PRMT1 (Table 1). DNA binding activity of 53BP1 is enhanced by the methylation of RGG motifs and stimulation of NHEJ pathway. The binding of 53BP1 to dsDNA break simultaneously inhibit the MRE11 binding and processing of DNA ends and thereby inhibiting HR mediated repair (Boisvert et al. 2005b). This 53BP1 methylation may be significant in mature neuronal cells owing to the obligatory dependence of post mitotic cells on the NHEJ pathway for DSB repair. Methylation of MRE11 by PRMT1 promote both DNA end resection activity and activation of the DNA damage checkpoint signalling protein, ATR, to initiate repair by HR pathway (Boisvert et al. 2005a; Yu et al. 2012). Currently, it is unclear why the same PRMT1 enzyme methylate two critical factors involved in alternative pathways of DSB repair and whether this type of methylation is distinctively regulated in different tissues. The DNA binding activity of another DSB repair factor, BRCA1, is altered by methylation of RXR motifs present at the DNA binding region to regulate both transcription and tumor suppressor function (Guendel et al. 2010). However, whether this methylation of BRCA1 has any role in brain cells is not understood or studied yet. The clues obtained from such studies on proliferating cancer cells provide an opportunity to determine how their activity impart on the neuronal DDR and cell death pathways.

Table 1.

Arginine methylated proteins involved in DDR and cell cycle

| Protein | Arginine (R) residue methylated | PRMT | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 53BP1 | R1398, R1400, R1401 | PRMT1 | (Boisvert et al. 2005b) |

| MRE11 | R566, R600 | PRMT1 | (Boisvert et al. 2005a) |

| BRCA1 | R residues between 504 and 802 | PRMT1 | (Guendel et al. 2010) |

| RUVBL1 | R205 | PRMT5 | (Clarke et al. 2017) |

| TDP1 | R361, R586 | PRMT5 | (Rehman et al. 2018) |

| hnRNPUL1 | R584, 5618, R620, R645, R656 | PRMT1 | (Gurunathan et al. 2015) |

| TOP3B | R833, R835 | PRMT1,3,6 | (Huang et al. 2018) |

| DDX5 | R502 | PRMT5 | (Mersaoui et al. 2019) |

| KLF4 | R417, R419, R420 | PRMT5 | (Hu et al. 2015) |

| FEN1 | R192 | Unknown | (Guo et al. 2010). |

| RAD9 | R172, R174, R175 | PRMT5 | (He et al. 2011) |

Symmetric dimethylation of RUVBL1 (Resistant to ultraviolet B-like protein 1) by PRMT5 plays important roles switching NHEJ to error-free HR during S/G2 phase of the cell cycle (Clarke et al. 2017). RUVBL1 is a coactivator of Histone H4 acetyltransferase TIP60. Mechanistically, acetylated Histone H4 (H4K16ac) prevents the binding of NHEJ factor 53BP1 to the DSBs and allows the HR pathway to repair the break. The hnRNPUL1 is recruited to the DNA DSBs by interacting with NBS1 protein present in the MRN complex (Polo et al. 2012). This recruitment is important for the DNA end resection pathway required for the repair of the breaks by HR. Methylation of hnRNPUL1 by PRMT1 was shown to be required for their recruitment to chromatin and DDR functions (Gurunathan et al. 2015). It appears that arginine methylation of RUVBL1 and hnRNPUL1 may be significant in neuronal cells as the mature neurons depends on HR pathway for the DSB repair. Moreover, since these factors regulate transcription and many neurodegenerative disease show problems in resolving R-loops (see section 3.1.2); future studies addressing these aspects is expected to provide how these factors and their arginine methylation is important in neuronal genome stability maintenance.

Mutation in tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterase 1 (TDP1) has been linked to Spinocerebellar ataxia with axonal neuropathy (SCAN1). TDP1 is involved in the repair of single strand breaks created by topoisomerase 1 (Top1) enzyme. PRMT5 mediated methylation of TDP1 is important for the repair of TOP1 associated DNA damage. Failure in the ligation of TOP1 cleaved DNA may result in deleterious covalently bound DNA-TOP1 cleavage complex (TOP1cc) that block replication fork and transcription. These TOPcc road blocks are cleaved by TDP1 and the arginine methylation enhances its activity (Rehman et al. 2018). It is likely that, in addition to TDP1 mutation, any imbalance in its methylation could also results in SCAN1.

Arginine methylation and RNA-DNA hybrid (R-loops) associated genomic instability

R-loops are three stranded structure composed of RNA-DNA hybrid and the displaced single stranded DNA, formed physiologically during the transcription (Aguilera and Garcia-Muse 2012). Although R-loops can positively influence gene expression, DNA replication, and DNA repair, it can also induce genomic instability (Alzu et al. 2012; Stirling et al. 2012). Even though RNA helicases, RNase H, and topoisomerase can dissolve the RNA-DNA hybrids under physiological conditions, persistent R-loops can cause DNA breaks and lead to both nuclear and mitochondrial genomic instability (Skourti-Stathaki et al. 2011; Wahba et al. 2011; Silva et al. 2018). Mechanistically, activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) can act on the cytosine residues to form uracil on the displaced single stranded DNA in R-loops that are further processed by the BER enzyme, uracil DNA glycosylase, generating single-stranded DNA breaks (Basu et al. 2011). In particular, the R-loops are associated with several repeat-expansion associated neurodegenerative diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) frontotemporal dementia (FTD), Friedreich ataxia (FRDA), fragile X syndrome (FXS), and fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) (Haeusler et al. 2014; Loomis et al. 2014; Groh et al. 2014). There are about 40 repeat associated human disorders are reported and it is not clear yet whether R-loops are involved in all these disease pathogenies (Groh et al. 2014). Since repeats can affect movement of RNA polymerases, it is likely that R-loops formed could be a common pathogenic mechanism in those diseases as well. Genetic mutations in the R-loop processing factors have been implicated in a large number of motor neuron diseases (Perego et al. 2019). In addition, transcription associated RNA splicing issues seen in repeat disease could also induce genomic instability, either directly or indirectly as seen in the case of myelodysplastic syndromes (Chen et al. 2018). Mammalian Topoisomerase 3B (TOP3B) is involved in resolving both negatively supercoiled DNA and R-loops formed by the RNA polymerase II transcription (Yang et al. 2014). TOP3B is methylated by PRMT1, 3, and 6 at the GAR motif (Huang et al. 2018). Methylation deficient mutant of TOP3B showed reduced activity and increased R-loops, in vitro. These results suggest that methylation of TOP3B may be an important factor involved in preventing R-loop mediated genomic instability. The RNA helicase, DDX5 was reported to unwind the RNA-DNA hybrids. Arginine methylation of DDX5 by PRMT5 is important for its association with XRN2 exonuclease and thereby suppress R-loop accumulation and genomic instability (Mersaoui et al. 2019). Considering the important roles played by R-loops processing factors in many neurodegenerative diseases, understanding their regulation by methylation or together with other PTMs may help to provide the molecular mechanism of pathogenesis and possible identification of therapeutic targets.

Arginine methylation and stress granules dynamics

The cytoplasmic stress granules (SG) are composed of untranslated mRNA, ribosomal subunits, eIFs, and various aggregated proteins. PTMs such as methylation and ubiquitination are shown to be involved in regulating SG dynamics. Mutations in TDP-43 and FUS/TLS gene was identified in familial form of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FLTD). In the patient’s brain, stress granules with mutant TDP-43, FUS/TLS, and heavily ubiquitinated proteins were detected (Neumann et al. 2006; Cairns et al. 2007; Kwiatkowski et al. 2009; Vance et al. 2009). PRMT1 was found in complex with TDP43 and FUS/TLS in the stress granules (Yamaguchi and Kitajo 2012) (Table 2). TDP-43 is recruited to the DSB and act as a scaffold protein for the NHEJ factor, XRCC-Ligase 4 complex (Mitra et al. 2019; Guerrero et al. 2019). FUS mediate the recruitment of XRCC1/DNA Ligase III to the oxidatively damaged DNA that is required for the ligation of DNA breaks (Wang et al. 2018; Wang and Hegde 2019). It still eludes the researchers as to whether arginine methylation play any direct role in regulating TDP-43 or FUS functions in RNA/DNA binding and DNA repair activity. Recently, the arginine methylated FUS/TLS was shown to be involved in the stress granule clearance by autophagy (Chitiprolu et al. 2018). Another factor involved in the assembly and disassembly of stress granules is the ubiquitin-associated protein 2-like (UBAP2L). PRMT1 mathylates the RGG motif present in the UBAP2L (Huang et al. 2019). PRMT7 mediated methylation of eIF2α is also important for stress granule formation (Haghandish et al. 2019). It will be interesting to study in the future to see the contribution of methylation of on stress granule dynamics and whether this can be modulated therapeutically to control the progression of neurodegenerative diseases.

Table 2.

Arginine and lysine methylated proteins implicated in Neurodegeneration

| Protein | Amino acid residue | PRMT/PKMT | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arginine methylation | |||

| FUS/TLS | Unknown | PRMT1 | (Yamaguchi and Kitajo 2012) |

| C/EBPα | R35, R156, R165 | PRMT1 | (Liu et al. 2019) |

| FOXO1 | R248, R150 | PRMT1 | (Yamagata et al. 2008) |

| eIF2α | R52, R53, R54, R56 | PRMT7 | (Haghandish et al. 2019) |

| PTEN | R159 | PRMT6 | (Feng et al. 2019) |

| Lysine methylation | |||

| Tau | K163, K174, K180, K254, K267, K290 | Unknown | (Thomas et al. 2012) |

| Tau | K24, K44, K67, K190, K259, K267, K290, K311, K317, K353, K385 | Unknown | (Thomas et al. 2012) |

| ERα | K302 | SET7/9 | (Subramanian et al. 2008) |

| ERα | K266 | SMYD2 | (Jiang et al. 2014) |

| ERα | K235 | G9a/GLP | (Zhang et al. 2016) |

| HSPA1A (HSP72) | K561 | SETD1A | (Cho et al. 2012) |

| HSPA1, HSPA5, HSPA8 | K561 | METTL21A | (Cho et al. 2012) |

| ANT | K52 | FAM173A (mitochondrial) | (Malecki et al. 2019) |

| AKT | K140K142, K64 | SETDB1 | (Guo et al. 2019) |

| AKT | K64 | SETDB1 | (Wang et al. 2019) |

Arginine methylation of cell cycle regulators and their cross-talk with other PTMs

KLF4 is a short-lived transcription factor involved in DDR, cell cycle progression and apoptosis. Under physiological conditions the KL4 is regulated by E3 ubiquitin ligase VHL (von Hippel-Lindau) mediated proteasomal degradation (Gamper et al. 2012). However, upon DNA damage, KLF4 is methylated by PRMT5 to inhibit the ubiquitination and degradation that in turn arrests cell cycle and apoptosis by increasing the expression of p21 (Hu et al. 2015).

A crosstalk between methylation and phosphorylation has been reported in the flap endonuclease FEN1. Methylated FEN1 attenuates the nearby phosphorylation site to facilitate binding to PCNA to regulate replication and repair (Guo et al. 2010). Rad9 (9–1-1 complex) is a conserved multifaceted protein involved in both DNA repair and cell cycle progression (Lieberman 2006). Methylation of Rad9 by PRMT5 is critical for its role in both DNA repair and checkpoint activation (He et al. 2011).

Methylation of p53 by PRMT5 and its interaction with methylated p300/CBP (methylation by CARM1) is involved in cell cycle arrest during DDR (Lee and Stallcup 2011). p53 is also highly methylated at lysine residues and regulated multiple signalling pathways (discussed in section 3.2.1). The basic leucine zipper (bZIP) family of transcription factor, C/EBPα is an inhibitor of cell division. C/EBPα is highly modified with various PTMs including phosphorylation, acetylation, SUMOylation, and methylation. All these modifications affect DNA-binding ability or interacting with other proteins. Methylated C/EBPα inhibit the binding of HDAC3 and de-repress Cyclin D1 that eventually leads to cell proliferation (Liu et al. 2019). How the multiple PTMs present in C/EBPα influence each other is not clearly understood.

The forkhead transcription factors of class O (FOXO1) is methylated by PRMT1 and it prevent its degradation by proteasome through the inhibition of AKT mediated phosphorylation and subsequent inhibition of apoptosis under oxidative damage (Yamagata et al. 2008). Additionally, AKT functions are also known to be regulated by lysine methylation (see below). Tumor suppressor protein PTEN is methylated by PRMT6 and modulate pre-mRNA alternate splicing (Feng et al. 2019). Although, the role of these factors in DDR and cell cycle factors and their methylation in proliferating cells are studied in detail, their underlying consequences in neuronal cells are still not lucidly outlined yet.

Lysine methylation

Bulk of the literature report the implications of lysine methylation of histones associated with cancer. In addition to altered histone lysine methylations resulting in dysregulated gene expression proven to be detrimental to brain cells; quite a large number of non-histone lysine methylation have also been observed playing critical role in the pathogenies of neurodegenerative disease (Tables 2 and 3). The mono, di or tri methylation of lysine residues on these proteins is carried out by two classes of PKMTs: (a) SET domain and (b) Non-SET domain containing PKMTs. Whereas, a set of 50 SET domain containing proteins with not so clear functions have been identified in humans with the existence of non-SET domain enzymes like DOT1L, METTL, METTL21A, and CaM KMT seen to be belonging to Seven-β-strand (7βS) family of lysine methylases (Del Rizzo and Trievel 2014; Falnes et al. 2016; Hamamoto et al. 2015). The mono and di methyl lysine residues are removed enzymatically by the demethylases (KDMs), Lysine-Specific Demethylase (LSD1/KDM1A) and LSD2 (KDM1B) and demethylases harboring Jumonji-C (JmjC) domain remove all three types of methylated lysine residues (Shi and Tsukada 2013; Agger et al. 2007; Whetstine et al. 2006).

Table 3.

Lysine methylated non-histone proteins involved in DDR, cell proliferation, and cell death pathways

| Protein | Lysine (R) residue methylated | PKMT | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| P53 | K382 | SETD8 | (Shi et al. 2007) |

| P53 | K372 | SETD7 | (Chuikov et al. 2004) |

| P53 | K370 | SMYD2 | (Huang et al. 2006) |

| P53 | K373 | G9a/GLP | (Huang et al. 2010) |

| E2F1 | K185 | SET9 | (Xie et al. 2011) |

| RB | K810/K873 | SET7/9 | (Saddic et al. 2010) |

| RB | K860 | SMYD2 | (Carr et al. 2014) |

| DNA-PKc | K1150, K2746, K3248 | Unknown | (Liu et al. 2013) |

| KU80 | K7 | Unknown | (Liu et al. 2013) |

| UHRF1 | K385 | SET7 | (Hahm et al. 2019) |

| SUV39H1 | K105, K123 | SET7/9 | (Wang et al. 2013a) |

| β-catenin | K180 | SET7/9 | (Shen et al. 2015) |

| PARP1 | K528 | SMYD2 | (Kassner et al. 2013) |

| PARP1 | K508 | SET7/9 | (Piao et al. 2014) |

| PCNA | K248 | SET8 | (Takawa et al. 2012) |

| Rad18 | – | SETD1A | (Alsulami et al. 2019) |

| SIRT1 | K233, K235, K236, K238 | SET7/9 | (Liu et al. 2011) |

| FOXO3 | K270 | SET9 | (Xie et al. 2012) |

| HSP90AB1 | K531 K574 | SMYD2 | (Hamamoto et al. 2014) |

| HSP70 | K561 | SETD1A | (Cho et al. 2012) |

Lysine methylation of proteins involved in DNA repair and cell cycle regulation

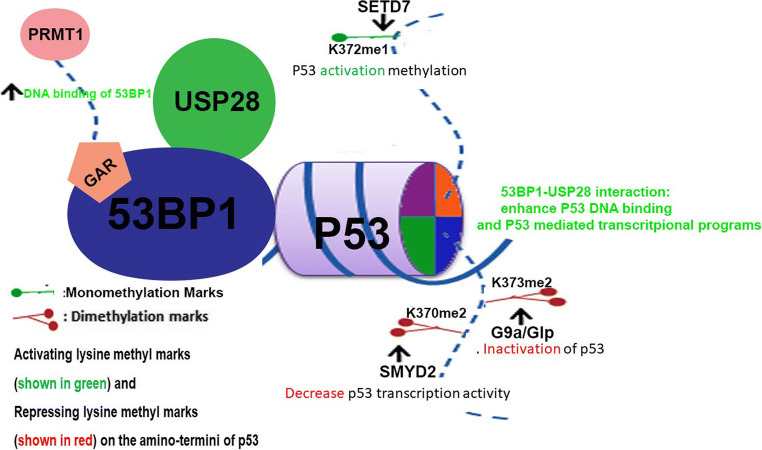

The cellular functions of tumor suppressor protein, p53, is regulated by various PTMs including methylation of multiple lysine residues (Table 3). Both the stability and transcription activity of p53 is enhanced by SETD7 mediated methylation of lysine 372 (Chuikov et al. 2004) restricting the localisation of p53 at the nucleus. Lysine 370 methylation of p53 by (SMYD2) play important roles in cell cycle regulation and apoptosis (Huang et al. 2006). K370 methylation was shown to decrease the transcriptional activity of p53 (decreased CDKN1A expression) and increased apoptosis. Mechanistically, the double strand break repair factor, 53BP1, through their Tudor domains interact with K370 dimethylated p53 and increase p53 function that eventually induce apoptosis (Fig. 1). Consistent with this, the demethylase LSD1 can demethylate and repress the activity of p53 modulating the regulation of p53 activity. Additionally, K372 methylated p53 inhibits the binding of SMYD2 and decreased methylation of K370 (Huang et al. 2006). Another p53 methylation K382 by SETD8 was reported to inhibit the transcription activity of p53 in cancer cells (Shi et al. 2007). K373 dimethylation by G9a/Glp methylase was also reported to regulate the tumor suppressor activity of p53 (Huang et al. 2010). The arginine methylation of 53BP1 (PRMT1 mediated) increase their affinity for DNA and thus helps to recruits various interacting factors including p53 and the deubiquitinase, USP28 (Cuella-Martin et al. 2016) (Fig. 1). The interaction of 53BP1 with USP28 is required for the cell cycle checkpoint function while their role in DNA repair is not clear yet (Fig. 1). p53 cellular functions are also modulated by SIRT1 dependent acetylation. SIRT1 histone deacetylase was shown to interact with SET7/9 and in response to DNA. This interaction in turn suppress the interaction between SIRT1 and p53 results in decreased acetylated p53 levels and regulate p53 function (Liu et al. 2011). The functions of multiple p53 lysine methylation was mostly studied in relation to rapidly dividing cancer cells and the precise roles of such methylations of p53 in neuronal DNA damage response and cell death require further detailed research.

Fig. 1.

Multiple Lysine methylation regulate cellular functions of p53. Activating methylation (K732me1) by SETD7 and repressing methylation (K370me2, K373me2) by SMYD2 and G9a/Glp methylases, respectively, are shown. Arginine methylation of 53BP1 also regulate their DNA binding, interaction with p53 and USP28 and thereby modulating transcriptional activity of p53

Lysine methylation of NHEJ factors, DNA-PKc and Ku80, are recognized by HP1β also mediating the localization of other DDR proteins (Table 3). NHEJ repair is also promoted by MDC1 demethylation by JMJD1C (Liu et al. 2013; Watanabe et al. 2013). The demethylation of MDC1 enhance the RAP80-BRCA1 to damage site, RNF8 mediated polyubiquitination, and reduce RAD51 foci formation thus helping to choose the appropriate DNA repair pathway (Lu and Matunis 2013). Rad18 is an ubiquitin E3 ligase enzyme playing important roles in bypassing the DNA damage during replication in a process known as DNA Damage Tolerance (DDT) (Branzei and Szakal 2016). Rad18 forms complex with E2 enzyme Rad6 and catalyses the K63 linked ubiquitination of replication processivity clamp PCNA when cells encounter DNA damage during replication. This modification of PCNA helps to recruit various HR proteins or trans lesion synthesis polymerases to bypass the DNA lesions and resume replication. Recently, physical interaction between Rad18 and SETD1A methylase was observed (Alsulami et al. 2019). Depletion of SETD1A or RAD18 individually leads to defect in cells response to DNA damage while depletion of both the factors together resulted in epistatic effect. This clearly suggest that these two proteins functions in the same genetic pathway. It is not clear currently whether these interaction results in the methylation of Rad18 and can direct its role in DDT and DNA repair in neuronas. PCNA methylation by SETD8 was shown to inhibit its polyubiquitination and enhanced interaction with the flap endonuclease FEN1 (Takawa et al. 2012). Although, this modification is important for the maturation of Okazaki fragments in the lagging strand, the mechanistic details of their defects are not completely understood. PCNA polyubiquitination in response to DNA damage in S phase is enhanced by lysine methylation of UHRF1 (Ubiquitin-like with PHD and RING finger domains) by SET7 and promote HR repair (Hahm et al. 2019).

Tumor suppressor retinoblastoma (RB) is methylated by both SMYD2 and SET7/9 at two different lysine residues (Saddic et al. 2010; Carr et al. 2014). SET7/9 mediated methylation is recognized by 53BP1 Tudor domain of 53BP1 and influences the DDR. The transcription factor FOXO induce neuronal cell death by increasing the expression of pro apoptotic Bim and FasL (van der Horst and Burgering 2007). Methylation of FOXO by SET9 (K270) reduces its transcription activity by inhibiting its DNA binding thus preventing oxidative stress conditions (Xie et al. 2012). The SUV39H1 is a histone H3K9 methylase whose activity is regulated by its own methylation by another methylase SETD7. SUV39H1 methylation activity is inhibited by SETD7 results in heterochromatin relaxation and genomic instability (Wang et al. 2013a). SETD7 also helps to recruit poly-ADP-ribosyl transferase 1 (PARP1) to the DNA damage sites by methylating the lysine residues (Kassner et al. 2013). Methylation of PARP1 by SMYD2 was shown to enhance its poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation activity under oxidative stress (Piao et al. 2014). Methylation of HSP90AB1 by SMYD2 increase the cancer survival by enhancing its interaction with co-chaperons CDC37 and STIP1 (Hamamoto et al. 2014). Oxidative stress induced methylation β-catenin SET7/9 was reported to play a role in cancer cell proliferation (Shen et al. 2015). From the above discussed literature, it is clear that lysine methylation plays important regulatory role in cell cycle regulation in proliferating cells. Whether these factors and their methylation is important for neuronal cell survival under genotoxic stress is still an open question.

Lysine methylation of mitochondrial proteins

Several lysine methylated mitochondrial proteins have been identified (Hornbeck et al. 2012) (Table 2). The three mitochondrial specific methyltransferases are: FAM173B, METTL20, and METTL12 targets ATP synthase c-subunit (trimethylation of K43), β-subunit of electron transfer flavoprotein (ETFβ) at K200 and K203, and K395 of mitochondrial citrate synthase (CS), respectively (Malecki et al. 2015; Rhein et al. 2017). Recently, FAM173B was shown to methylate another mitochondrial enzyme, Adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT) (Malecki et al. 2019). All these modifications affect the mitochondrial respiration and ATP production. Many experimental reports suggest that mitochondrial DNA damage responses play game changing roles in aging and in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases such as AD, PD, HD and ALS (Cha et al. 2015).. It has been seen that the damaged DNA lesions by oxidative stress are much higher in mtDNA of AD post-mortem tissues. The link between mitochondrial alteration and the progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is still ambiguous but some mutation analysis studies reveal that SOD1 is the cause of mitochondrial dysfunction in ALS (Pansarasa et al. 2018). Some of the reports display downregulation of the mitochondrial BER enzymes, OGG1 and POL-γ, in mutant SOD1 transgenic mice (Coppede 2011). Studies have suggested that mtDNA is a major target of mutant huntingtin protein (mHTT) associated oxidative stress and may lead to mitochondrial alteration and that BER enzyme APE1 is one of the crucial targets in the maintenance of mitochondrial activity in HD. Wang et al. suggested that HD cells, which have excessive mitochondrial Ca2+ levels, show higher level of mtDNA damage because of ROS generation (Wang et al. 2013b). Despite the fact that both methylases and DNA repair factors are present in the mitochondria, a direct role for methylation in mitochondrial DNA repair factors are not reported yet.

Lysine methylation and cross talk with other PTMs

Lysine methylation can affect phosphorylation, acetylation, and ubiquitination of nearby by or distant amino acids, directly or indirectly. K185 methylation of transcription factor E2F1 by SETD7 plays important roles in DNA damage response (Xie et al. 2011). Under conditions of DNA damage, acetylation and phosphorylation of E2F1 is inhibited by its methylation while promoting polyubiquitination and degradation. Diminished activity of E2F1 increase the activation of TP73, a pro-apoptotic gene. Methylation of E2F1 is reversed by the action of, LSD1 demethylase. The unmethylated E2F is acetylated by KAT2B and phosphorylated by CHK2 that influence the DNA damage induced cell death (Kontaki and Talianidis 2010). Methylation of kinases and phosphatases can affect their activity and ultimately altering the phosphorylation and acetylation status of their substrates, respectively (Mazur et al. 2014). Phosphorylated histone H3 (H3S10) inhibit the binding of chromodomain containing HP1β to the nearby methylated H3K9 chromatin mark (Fischle et al. 2005). Whereas the same methylated residue is recognized by tandem Tudor domain containing UHRF1 ubiquitin ligase (Rothbart et al. 2012). UHRF1 itself is methylated by SET7 to promote HR (see section 3.2.1). Since ubiquitination and methylation occurs on lysine residues, it was not surprising to find both these modifications competing each other under different cellular conditions. In this way, methylation can increase the stability of a protein by inhibiting lysine ubiquitination and their proteasomal degradation (Desiere et al. 2005). For example, H2BK120 methylation by EZH2 competitively inhibits ubiquitylation and suppresses the transcription (Kogure et al. 2013). In some cases, decrease in protein stability due to methylation was also reported. The so called “methyl degron” where the ubiquitin E3 enzyme complex, DCAF1–DDB1–CUL4, recognizes the methylated lysine residues on its substrates and ubiquitinate a neighbouring lysine residue within the same substrate protein and targets them for degradation (Lee et al. 2012). A complete understanding of the dynamic PTMs occurring on same protein in response to cellular stress is important to delineate the underlying disease mechanisms.

Lysine methylation of aggregated proteins in neurodegenerative diseases

AD is characterized by the presence of intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) of amyloid-beta (Aβ) and tau proteins in the brain leads to neuronal cell death. Lysine methylation of tau was shown to be involved in its proper interaction with microtubule associated actin and proposed to be involved in the aggregation of tau protein in AD (Thomas et al. 2012; Thomas and Yang 2017). However, it was demonstrated later that tau is methylated in normal human brains and are unaffected by tauopathies, made a setback in this area of research (Morris et al. 2015). Since the PKMT responsible for tau methylation is identified yet, it is worth investigating further about tau methylation and its cross talk with other PTMs identified in tau. It is possible that a direct competition between ubiquitination and methylation for the same lysine residues and subtle changes in dynamic tau PTMs may dictate the aggregation of tau in the pathogenesis of AD. Estrogen and Estrogen receptors role in AD has been extensively investigated. It was reported that the two Estrogen receptors, ERα and ERβ, have opposite effects on tau aggregation either by increasing or decreasing its phosphorylation (Xiong et al. 2015). Methylation of ERα by SET7/9 stabilize and activate the estrogen dependent transcription (Subramanian et al. 2008). SMYD2 methylate ERα at K266 to inhibit its activity (Jiang et al. 2014), whereas methylation by G9a at K235 stimulate the activity (Zhang et al. 2016). In order to understand the mechanisms by which dynamic PTMs regulate the tau aggregation in AD, the interplay between these methylations has to be subjected to further investigations.

Heat-shock proteins (HSPs) are ATP driven molecular chaperones function in general stress-related protein folding activities. Since AD, PD, HD, ALS, and many other neurodegenerative disorders show protein aggregation as a common pathological mechanism, HSP proteins are considered as a potential therapeutic target. HSP functions are regulated by multiple PTMs. Consistent with this, HSP72 (HSPA1A) is methylated by SETD1A and HSPA1, HSPA5, and HSPA8 by another methylase, METTL21A (Cho et al. 2012). The methylation of HSPA8 reduce the interaction with α-synuclein, and may have a very important regulatory role in accumulation of aggregated proteins found in the Lewy bodies in PD brain (Jakobsson et al. 2013).

Concluding remarks

The ongoing efforts towards profiling the mammalian neural epigenome and its perturbations have opened up mechanistic and exhaustive insights into the epigenetic secrets of not only neurodegeneration but also the cell fate of neuronal cells and diseases afflicted as a consequence of the non-histone PTMs getting skewed. Limited knowledge on the functions of protein methylations in the biology of the nervous system makes it even more elusive as to whether the aberrant or normal methylations regulating DDR are actually a cause or consequence of the neurological diseases or pathologies. Thus, the future certainly looks promising to unfold the hidden mechanisms of these aberrant non-histone protein methylation. Therefore, todays state of knowledge apparently indicates that not a single modification but truly a combination of several modifications as drug targets could be the clue to the success of future epigenetic-based therapeutic strategies for neurological disorders. Hence, mapping of the protein-protein, protein-RNA and protein-DNA interactions and the networks governing DNA repair pathways in neuronal cells will unfold an unexplored and rare dimension in the pursuit to discover the entire landscape of neural epigenome dictating the onset and etiology of neurodegenerative diseases. Thus, coupling the discovery of novel non-histone methylation substrates along with their cognate methyl transferases and demethylases will provide in near future, suitable druggable targets of therapeutic significance serving as foundation of clinical epigenomics in the days to come.

Acknowledgments

MU thank Prof. Asha Kishore, Dr. Srinivas G, and Dr. Cibin TR, SCTIMST, for their constant encouragement, stimulating discussion, suggestions and support throughout.

Abbreviations

- 53BP1

p53 binding protein

- Aβ

Amyloid-beta

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADMA/Rme2a

Asymmetric dimethylarginine

- AID

Activation-Induced cytidine deaminase

- ALS

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- AOA1

Ataxia-ocular motor Apraxia 1

- APTX

Aprataxin

- ATLD

Ataxia-telangiectasia like disease

- ATM

Ataxia telangiectasia mutated

- ATR

Ataxia telangiectasia mutated and Rad3 related

- BER

Base excision repair

- BRCA1

Breast cancer susceptibility protein 1

- BS

Bloom syndrome

- CS

Cockayne syndrome

- DDR

DNA damage response

- DSB

Double strand breaks

- ETFβ

Electron transfer flavoprotein

- FOXO1

Forkhead transcription factors of class O

- FRDA

Friedreich ataxia

- FTD

Frontotemporal dementia

- FUS/TLS

Fused in sarcoma/Translocated in liposarcoma

- FXS

Fragile X syndrome

- FXTAS

Fragile X-associated Tremor/Ataxia syndrome

- GAR/RGG

Glycine-and-arginine-rich

- GG-NER

Global genomic nucleotide excision repair

- HD

Huntington’s disease

- HP1

Heterochromatin protein 1

- HR

Homologous recombination

- JMJC

Jumonji domain-containing

- MCSZ

Microcephaly with seizures

- MMA/Rme1

Monomethylated arginine

- MMR

Mismatch repair

- MRE11

Meiotic recombination 11

- mtDNA

Mitochondrial DNA

- NBS

Nijmegen breakage syndrome

- NER

Nucleotide excision repair

- NFT

Neurofibrillary tangles

- NHEJ

Non-homologous end joining

- PAD

Protein arginine deiminases

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- PKMT

Protein lysine methyltransferases

- PNKP

Polynucleotide Kinase/Phosphatase

- PRMT

Protein arginine Methyltransferases

- PTMs

Post translational modifications

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- RTS

Rothmund–Thomson syndrome

- SCAN1

Spinocerebellar ataxia with axonal neuropathy

- SDMA/Rme2s

Symmetric dimethylarginine 4

- SSB

Single strand breaks

- TC-NER

Transcription coupled nucleotide excision repair

- TDP1

Tyrosyl DNA-phosphodiesterase 1

- TDP-43

TAR DNA binding protein-43

- TOP1

Topoisomerase 1

- TOP1cc

TOP1 cleavage complex

- TTD

Trichothiodystrophy

- UBAP2L

Ubiquitin-associated protein 2-like

- VHL

von Hippel-Lindau

- XP

Xeroderma pigmentosum

- WS

Werner syndrome

Author contributions

MU and AM equally contributed in conceptualization, writing, and editing the manuscript.

Funding information

MU acknowledge the “seed fund” (#6113) from the Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology (SCTIMST).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

9/29/2020

The original version of this article unfortunately requires correction where the name of a methyltransferase was represented wrongly.

Contributor Information

Madhusoodanan Urulangodi, Email: drmadhusoodanan@sctimst.ac.in.

Abhishek Mohanty, Email: abhishek.m.iisc@gmail.com.

References

- Agger K, Cloos PA, Christensen J, Pasini D, Rose S, Rappsilber J, Issaeva I, Canaani E, Salcini AE, Helin K. UTX and JMJD3 are histone H3K27 demethylases involved in HOX gene regulation and development. Nature. 2007;449(7163):731–734. doi: 10.1038/nature06145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera A, Garcia-Muse T. R loops: from transcription byproducts to threats to genome stability. Mol Cell. 2012;46(2):115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsulami M, Munawar N, Dillon E, Oliviero G, Wynne K, Alsolami M, Moss C, Ó Gaora P, O'Meara F, Cotter D, Cagney G. SETD1A Methyltransferase is physically and functionally linked to the DNA damage repair protein RAD18. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2019;18(7):1428–1436. doi: 10.1074/mcp.RA119.001518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzu A, Bermejo R, Begnis M, Lucca C, Piccini D, Carotenuto W, Saponaro M, Brambati A, Cocito A, Foiani M, Liberi G. Senataxin associates with replication forks to protect fork integrity across RNA-polymerase-II-transcribed genes. Cell. 2012;151(4):835–846. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu U, Meng FL, Keim C, Grinstein V, Pefanis E, Eccleston J, Zhang T, Myers D, Wasserman CR, Wesemann DR, Januszyk K, Gregory RI, Deng H, Lima CD, Alt FW. The RNA exosome targets the AID cytidine deaminase to both strands of transcribed duplex DNA substrates. Cell. 2011;144(3):353–363. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender A, Krishnan KJ, Morris CM, Taylor GA, Reeve AK, Perry RH, Jaros E, Hersheson JS, Betts J, Klopstock T, Taylor RW, Turnbull DM. High levels of mitochondrial DNA deletions in substantia nigra neurons in aging and Parkinson disease. Nat Genet. 2006;38(5):515–517. doi: 10.1038/ng1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicker KL, Thompson PR. The protein arginine deiminases: structure, function, inhibition, and disease. Biopolymers. 2013;99(2):155–163. [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert FM, Dery U, Masson JY, Richard S. Arginine methylation of MRE11 by PRMT1 is required for DNA damage checkpoint control. Genes Dev. 2005;19(6):671–676. doi: 10.1101/gad.1279805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert FM, Rhie A, Richard S, Doherty AJ. The GAR motif of 53BP1 is arginine methylatedby PRMT1 and is necessary for 53BP1 DNA binding activity. Cell Cycle. 2005;4(12):1834–1841. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.12.2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgesius NZ, de Waard MC, van der Pluijm I, Omrani A, Zondag GC, van der Horst GT, Melton DW, Hoeijmakers JH, Jaarsma D, Elgersma Y. Accelerated age-related cognitive decline and neurodegeneration, caused by deficient DNA repair. J Neurosci. 2011;31(35):12543–12553. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1589-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branzei D, Foiani M. Regulation of DNA repair throughout the cell cycle. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(4):297–308. doi: 10.1038/nrm2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branzei D, Szakal B. DNA damage tolerance by recombination: molecular pathways and DNA structures. DNA Repair. 2016;44:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bras J, Alonso I, Barbot C, Costa MM, Darwent L, Orme T, Sequeiros J, Hardy J, Coutinho P, Guerreiro R. Mutations in PNKP cause recessive ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 4. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96(3):474–479. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann K, Schell M, Hoppe T, Kashkar H. Regulation of the DNA damage response by ubiquitin conjugation. Front Genet. 2015;6:98. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulau P, Zakrzewicz D, Kitowska K, Wardega B, Kreuder J, Eickelberg O. Quantitative assessment of arginine methylation in free versus protein-incorporated amino acids in vitro and in vivo using protein hydrolysis and high-performance liquid chromatography. BioTechniques. 2006;40(3):305–310. doi: 10.2144/000112081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns NJ, Neumann M, Bigio EH, Holm IE, Troost D, Hatanpaa KJ, Foong C, White CL, 3rd, Schneider JA, Kretzschmar HA, Carter D, Taylor-Reinwald L, Paulsmeyer K, Strider J, Gitcho M, Goate AM, Morris JC, Mishra M, Kwong LK, Stieber A, Xu Y, Forman MS, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM, Mackenzie IR. TDP-43 in familial and sporadic frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin inclusions. Am J Pathol. 2007;171(1):227–240. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney JP, Maser RS, Olivares H, Davis EM, Le Beau M, Yates JR, 3rd, et al. The hMre11/hRad50 protein complex and Nijmegen breakage syndrome: linkage of double-strand break repair to the cellular DNA damage response. Cell. 1998;93(3):477–486. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr SM, Munro S, Zalmas LP, Fedorov O, Johansson C, Krojer T, Sagum CA, Bedford MT, Oppermann U, la Thangue NB. Lysine methylation-dependent binding of 53BP1 to the pRb tumor suppressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(31):11341–11346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403737111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceccaldi R, Rondinelli B, D'Andrea AD. Repair pathway choices and consequences at the double-Strand break. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26(1):52–64. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha MY, Kim DK, Mook-Jung I. The role of mitochondrial DNA mutation on neurodegenerative diseases. Exp Mol Med. 2015;47:e150. doi: 10.1038/emm.2014.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Chen JY, Huang YJ, Gu Y, Qiu J, Qian H, Shao C, Zhang X, Hu J, Li H, He S, Zhou Y, Abdel-Wahab O, Zhang DE, Fu XD. The augmented R-loop is a unifying mechanism for Myelodysplastic syndromes induced by high-risk splicing factor mutations. Mol Cell. 2018;69(3):412–425. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitiprolu M, Jagow C, Tremblay V, Bondy-Chorney E, Paris G, Savard A, et al. A complex of C9ORF72 and p62 uses arginine methylation to eliminate stress granules by autophagy. Nature Communications. 2018;9(1):2794. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05273-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho HS, Shimazu T, Toyokawa G, Daigo Y, Maehara Y, Hayami S, et al. Enhanced HSP70 lysine methylation promotes proliferation of cancer cells through activation of Aurora kinase B. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1072. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuikov S, Kurash JK, Wilson JR, Xiao B, Justin N, Ivanov GS, et al. Regulation of p53 activity through lysine methylation. Nature. 2004;432(7015):353–360. doi: 10.1038/nature03117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccia A, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol Cell. 2010;40(2):179–204. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke TL, Sanchez-Bailon MP, Chiang K, Reynolds JJ, Herrero-Ruiz J, Bandeiras TM, Matias PM, Maslen SL, Skehel JM, Stewart GS, Davies CC. PRMT5-dependent methylation of the TIP60 coactivator RUVBL1 is a key regulator of homologous recombination. Mol Cell. 2017;65(5):900–916. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppede F. An overview of DNA repair in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Sci World J. 2011;11:1679–1691. doi: 10.1100/2011/853474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe SL, Movsesyan VA, Jorgensen TJ, Kondratyev A. Rapid phosphorylation of histone H2A.X following ionotropic glutamate receptor activation. Eur J Neurosci. 2006;23(9):2351–2361. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04768.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuella-Martin R, Oliveira C, Lockstone HE, Snellenberg S, Grolmusova N, Chapman JR. 53BP1 integrates DNA repair and p53-dependent cell fate decisions via distinct mechanisms. Mol Cell. 2016;64(1):51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabin J, Fortuny A, Polo SE. Epigenome maintenance in response to DNA damage. Mol Cell. 2016;62(5):712–727. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantuma NP, van Attikum H. Spatiotemporal regulation of posttranslational modifications in the DNA damage response. EMBO J. 2016;35(1):6–23. doi: 10.15252/embj.201592595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Date H, Onodera O, Tanaka H, Iwabuchi K, Uekawa K, Igarashi S, Koike R, Hiroi T, Yuasa T, Awaya Y, Sakai T, Takahashi T, Nagatomo H, Sekijima Y, Kawachi I, Takiyama Y, Nishizawa M, Fukuhara N, Saito K, Sugano S, Tsuji S. Early-onset ataxia with ocular motor apraxia and hypoalbuminemia is caused by mutations in a new HIT superfamily gene. Nat Genet. 2001;29(2):184–188. doi: 10.1038/ng1001-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza-Pinto NC, Wilson DM, 3rd, Stevnsner TV, Bohr VA. Mitochondrial DNA, base excision repair and neurodegeneration. DNA Repair. 2008;7(7):1098–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Rizzo PA, Trievel RC. Molecular basis for substrate recognition by lysine methyltransferases and demethylases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1839(12):1404–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desiere F, Deutsch EW, Nesvizhskii AI, Mallick P, King NL, Eng JK, Aderem A, Boyle R, Brunner E, Donohoe S, Fausto N, Hafen E, Hood L, Katze MG, Kennedy KA, Kregenow F, Lee H, Lin B, Martin D, Ranish JA, Rawlings DJ, Samelson LE, Shiio Y, Watts JD, Wollscheid B, Wright ME, Yan W, Yang L, Yi EC, Zhang H, Aebersold R. Integration with the human genome of peptide sequences obtained by high-throughput mass spectrometry. Genome Biol. 2005;6(1):R9. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-6-1-r9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar S, Gursoy-Yuzugullu O, Parasuram R, Price BD (2017) The tale of a tail: histone H4 acetylation and the repair of DNA breaks. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci 372(1731) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Falnes PO, Jakobsson ME, Davydova E, Ho A, Malecki J. Protein lysine methylation by seven-beta-strand methyltransferases. Biochem J. 2016;473(14):1995–2009. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Dang Y, Zhang W, Zhao X, Zhang C, Hou Z, et al. PTEN arginine methylation by PRMT6 suppresses PI3K-AKT signaling and modulates pre-mRNA splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(14):6868–6877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1811028116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischle W, Tseng BS, Dormann HL, Ueberheide BM, Garcia BA, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Funabiki H, Allis CD. Regulation of HP1-chromatin binding by histone H3 methylation and phosphorylation. Nature. 2005;438(7071):1116–1122. doi: 10.1038/nature04219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamper AM, Qiao X, Kim J, Zhang L, DeSimone MC, Rathmell WK, Wan Y. Regulation of KLF4 turnover reveals an unexpected tissue-specific role of pVHL in tumorigenesis. Mol Cell. 2012;45(2):233–243. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geoghegan V, Guo A, Trudgian D, Thomas B, Acuto O. Comprehensive identification of arginine methylation in primary T cells reveals regulatory roles in cell signalling. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6758. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong F, Miller KM. Histone methylation and the DNA damage response. Mutat Res. 2019;780:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh M, Silva LM, Gromak N. Mechanisms of transcriptional dysregulation in repeat expansion disorders. Biochem Soc Trans. 2014;42(4):1123–1128. doi: 10.1042/BST20140049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guendel I, Carpio L, Pedati C, Schwartz A, Teal C, Kashanchi F, Kehn-Hall K. Methylation of the tumor suppressor protein, BRCA1, influences its transcriptional cofactor function. PLoS One. 2010;5(6):e11379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero EN, Mitra J, Wang H, Rangaswamy S, Hegde PM, Basu P et al (2019) Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated TDP-43 mutation Q331K prevents nuclear translocation of XRCC4-DNA ligase 4 complex and is linked to genome damage-mediated neuronal apoptosis. Hum Mol Genet. 10.1093/hmg/ddz062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Guo A, Gu H, Zhou J, Mulhern D, Wang Y, Lee KA, Yang V, Aguiar M, Kornhauser J, Jia X, Ren J, Beausoleil SA, Silva JC, Vemulapalli V, Bedford MT, Comb MJ. Immunoaffinity enrichment and mass spectrometry analysis of protein methylation. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13(1):372–387. doi: 10.1074/mcp.O113.027870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Dai X, Laurent B, Zheng N, Gan W, Zhang J, Guo A, Yuan M, Liu P, Asara JM, Toker A, Shi Y, Pandolfi PP, Wei W. AKT methylation by SETDB1 promotes AKT kinase activity and oncogenic functions. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21(2):226–237. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0261-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z, Zheng L, Xu H, Dai H, Zhou M, Pascua MR, Chen QM, Shen B. Methylation of FEN1 suppresses nearby phosphorylation and facilitates PCNA binding. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6(10):766–773. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurunathan G, Yu Z, Coulombe Y, Masson JY, Richard S. Arginine methylation of hnRNPUL1 regulates interaction with NBS1 and recruitment to sites of DNA damage. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10475. doi: 10.1038/srep10475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeusler AR, Donnelly CJ, Periz G, Simko EA, Shaw PG, Kim MS, Maragakis NJ, Troncoso JC, Pandey A, Sattler R, Rothstein JD, Wang J. C9orf72 nucleotide repeat structures initiate molecular cascades of disease. Nature. 2014;507(7491):195–200. doi: 10.1038/nature13124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghandish N, Baldwin RM, Morettin A, Dawit HT, Adhikary H, Masson JY, Mazroui R, Trinkle-Mulcahy L, Côté J. PRMT7 methylates eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2alpha and regulates its role in stress granule formation. Mol Biol Cell. 2019;30(6):778–793. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E18-05-0330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm JY, Kim JY, Park JW, Kang JY, Kim KB, Kim SR, Cho H. Methylation of UHRF1 by SET7 is essential for DNA double-strand break repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(1):184–196. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamoto R, Saloura V, Nakamura Y. Critical roles of non-histone protein lysine methylation in human tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(2):110–124. doi: 10.1038/nrc3884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamoto R, Toyokawa G, Nakakido M, Ueda K, Nakamura Y. SMYD2-dependent HSP90 methylation promotes cancer cell proliferation by regulating the chaperone complex formation. Cancer Lett. 2014;351(1):126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper JW, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: ten years after. Mol Cell. 2007;28(5):739–745. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto S, Anai H, Hanada K. Mechanisms of interstrand DNA crosslink repair and human disorders. Genes Environ. 2016;38:9. doi: 10.1186/s41021-016-0037-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He W, Ma X, Yang X, Zhao Y, Qiu J, Hang H. A role for the arginine methylation of Rad9 in checkpoint control and cellular sensitivity to DNA damage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(11):4719–4727. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegde ML, Bohr VA, Mitra S. DNA damage responses in central nervous system and age-associated neurodegeneration. Mech Ageing Dev. 2017;161(Pt A):1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoch NC, Hanzlikova H, Rulten SL, Tetreault M, Komulainen E, Ju L, et al. XRCC1 mutation is associated with PARP1 hyperactivation and cerebellar ataxia. Nature. 2017;541(7635):87–91. doi: 10.1038/nature20790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornbeck PV, Kornhauser JM, Tkachev S, Zhang B, Skrzypek E, Murray B, Latham V, Sullivan M. PhosphoSitePlus: a comprehensive resource for investigating the structure and function of experimentally determined post-translational modifications in man and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D261–D270. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath S, Langfelder P, Kwak S, Aaronson J, Rosinski J, Vogt TF, Eszes M, Faull RL, Curtis MA, Waldvogel HJ, Choi OW, Tung S, Vinters HV, Coppola G, Yang XW. Huntington's disease accelerates epigenetic aging of human brain and disrupts DNA methylation levels. Aging. 2016;8(7):1485–1512. doi: 10.18632/aging.101005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D, Gur M, Zhou Z, Gamper A, Hung MC, Fujita N, et al. Interplay between arginine methylation and ubiquitylation regulates KLF4-mediated genome stability and carcinogenesis. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8419. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Chen Y, Dai H, Zhang H, Xie M, Zhang H, Chen F, Kang X, Bai X, Chen Z (2019) UBAP2L arginine methylation by PRMT1 modulates stress granule assembly. Cell Death Differ 1–15. 10.1038/s41418-019-0350-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Huang J, Dorsey J, Chuikov S, Perez-Burgos L, Zhang X, Jenuwein T, et al. G9a and Glp methylate lysine 373 in the tumor suppressor p53. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(13):9636–9641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.062588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Perez-Burgos L, Placek BJ, Sengupta R, Richter M, Dorsey JA, Kubicek S, Opravil S, Jenuwein T, Berger SL. Repression of p53 activity by Smyd2-mediated methylation. Nature. 2006;444(7119):629–632. doi: 10.1038/nature05287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Wang Z, Narayanan N, Yang Y. Arginine methylation of the C-terminus RGG motif promotes TOP3B topoisomerase activity and stress granule localization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(6):3061–3074. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SP, Bartek J. The DNA-damage response in human biology and disease. Nature. 2009;461(7267):1071–1078. doi: 10.1038/nature08467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SP, Durocher D. Regulation of DNA damage responses by ubiquitin and SUMO. Mol Cell. 2013;49(5):795–807. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson ME, Moen A, Bousset L, Egge-Jacobsen W, Kernstock S, Melki R, Falnes PØ. Identification and characterization of a novel human methyltransferase modulating Hsp70 protein function through lysine methylation. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(39):27752–27763. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.483248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Trescott L, Holcomb J, Zhang X, Brunzelle J, Sirinupong N, Shi X, Yang Z. Structural insights into estrogen receptor alpha methylation by histone methyltransferase SMYD2, a cellular event implicated in estrogen signaling regulation. J Mol Biol. 2014;426(20):3413–3425. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassner I, Andersson A, Fey M, Tomas M, Ferrando-May E, Hottiger MO. SET7/9-dependent methylation of ARTD1 at K508 stimulates poly-ADP-ribose formation after oxidative stress. Open Biol. 2013;3(10):120173. doi: 10.1098/rsob.120173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JJ, Lee SY, Miller KM. Preserving genome integrity and function: the DNA damage response and histone modifications. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2019;54(3):208–241. doi: 10.1080/10409238.2019.1620676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogure M, Takawa M, Saloura V, Sone K, Piao L, Ueda K, et al. The oncogenic polycomb histone methyltransferase EZH2 methylates lysine 120 on histone H2B and competes ubiquitination. Neoplasia. 2013;11:1251–1261. doi: 10.1593/neo.131436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontaki H, Talianidis I. Lysine methylation regulates E2F1-induced cell death. Mol Cell. 2010;39(1):152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer KH, Patronas NJ, Schiffmann R, Brooks BP, Tamura D, DiGiovanna JJ. Xeroderma pigmentosum, trichothiodystrophy and Cockayne syndrome: a complex genotype-phenotype relationship. Neuroscience. 2007;145(4):1388–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski TJ, Jr, Bosco DA, Leclerc AL, Tamrazian E, Vanderburg CR, Russ C, et al. Mutations in the FUS/TLS gene on chromosome 16 cause familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2009;323(5918):1205–1208. doi: 10.1126/science.1166066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen SC, Sylvestersen KB, Mund A, Lyon D, Mullari M, Madsen MV, et al. Proteome-wide analysis of arginine monomethylation reveals widespread occurrence in human cells. Science Signal. 2016;9(443):rs9. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aaf7329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laugel V, Dalloz C, Durand M, Sauvanaud F, Kristensen U, Vincent MC, Pasquier L, Odent S, Cormier-Daire V, Gener B, Tobias ES, Tolmie JL, Martin-Coignard D, Drouin-Garraud V, Heron D, Journel H, Raffo E, Vigneron J, Lyonnet S, Murday V, Gubser-Mercati D, Funalot B, Brueton L, Sanchez del Pozo J, Muñoz E, Gennery AR, Salih M, Noruzinia M, Prescott K, Ramos L, Stark Z, Fieggen K, Chabrol B, Sarda P, Edery P, Bloch-Zupan A, Fawcett H, Pham D, Egly JM, Lehmann AR, Sarasin A, Dollfus H. Mutation update for the CSB/ERCC6 and CSA/ERCC8 genes involved in Cockayne syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2010;31(2):113–126. doi: 10.1002/humu.21154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JM, Lee JS, Kim H, Kim K, Park H, Kim JY, Lee SH, Kim IS, Kim J, Lee M, Chung CH, Seo SB, Yoon JB, Ko E, Noh DY, Kim KI, Kim KK, Baek SH. EZH2 generates a methyl degron that is recognized by the DCAF1/DDB1/CUL4 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex. Mol Cell. 2012;48(4):572–586. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YH, Stallcup MR. Roles of protein arginine methylation in DNA damage signaling pathways is CARM1 a life-or-death decision point? Cell Cycle. 2011;10(9):1343–1344. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.9.15379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber MR, Ma Y, Pannicke U, Schwarz K. Mechanism and regulation of human non-homologous DNA end-joining. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4(9):712–720. doi: 10.1038/nrm1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman HB. Rad9, an evolutionarily conserved gene with multiple functions for preserving genomic integrity. J Cell Biochem. 2006;97(4):690–697. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YW, Sanz LA, Xu X, Hartono SR, Chedin F (2015) Genome-wide DNA hypomethylation and RNA:DNA hybrid accumulation in Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome. eLife 4. 10.7554/eLife.08007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liu H, Galka M, Mori E, Liu X, Lin YF, Wei R, Pittock P, Voss C, Dhami G, Li X, Miyaji M, Lajoie G, Chen B, Li SS. A method for systematic mapping of protein lysine methylation identifies functions for HP1beta in DNA damage response. Mol Cell. 2013;50(5):723–735. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu LM, Sun WZ, Fan XZ, Xu YL, Cheng MB, Zhang Y. Methylation of C/EBPalpha by PRMT1 inhibits its tumor-suppressive function in breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2019;79(11):2865–2877. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-3211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Wang D, Zhao Y, Tu B, Zheng Z, Wang L, Wang H, Gu W, Roeder RG, Zhu WG. Methyltransferase Set7/9 regulates p53 activity by interacting with Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(5):1925–1930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019619108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomis EW, Sanz LA, Chedin F, Hagerman PJ. Transcription-associated R-loop formation across the human FMR1 CGG-repeat region. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(4):e1004294. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorton BM, Shechter D. Cellular consequences of arginine methylation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019;76(15):2933–2956. doi: 10.1007/s00018-019-03140-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Matunis MJ. A mediator methylation mystery: JMJD1C demethylates MDC1 to regulate DNA repair. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20(12):1346–1348. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas J, Lukas C, Bartek J. More than just a focus: the chromatin response to DNA damage and its role in genome integrity maintenance. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(10):1161–1169. doi: 10.1038/ncb2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiuri T, Mocle AJ, Hung CL, Xia J, van Roon-Mom WM, Truant R. Huntingtin is a scaffolding protein in the ATM oxidative DNA damage response complex. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26(2):395–406. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malecki J, Ho AY, Moen A, Dahl HA, Falnes PO. Human METTL20 is a mitochondrial lysine methyltransferase that targets the beta subunit of electron transfer flavoprotein (ETFbeta) and modulates its activity. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(1):423–434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.614115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malecki JM, Willemen H, Pinto R, Ho AYY, Moen A, Kjonstad IF, et al. Lysine methylation by the mitochondrial methyltransferase FAM173B optimizes the function of mitochondrial ATP synthase. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(4):1128–1141. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.005473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur PK, Reynoird N, Khatri P, Jansen PW, Wilkinson AW, Liu S, Barbash O, van Aller G, Huddleston M, Dhanak D, Tummino PJ, Kruger RG, Garcia BA, Butte AJ, Vermeulen M, Sage J, Gozani O. SMYD3 links lysine methylation of MAP3K2 to Ras-driven cancer. Nature. 2014;510(7504):283–287. doi: 10.1038/nature13320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon PJ. DNA repair deficiency and neurological disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(2):100–112. doi: 10.1038/nrn2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon PJ. Maintaining genome stability in the nervous system. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(11):1523–1529. doi: 10.1038/nn.3537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mersaoui SY, Yu Z, Coulombe Y, Karam M, Busatto FF, Masson JY, Richard S. Arginine methylation of the DDX5 helicase RGG/RG motif by PRMT5 regulates resolution of RNA:DNA hybrids. EMBO J. 2019;38(15):e100986. doi: 10.15252/embj.2018100986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra J, Guerrero EN, Hegde PM, Liachko NF, Wang H, Vasquez V et al (2019) Motor neuron disease-associated loss of nuclear TDP-43 is linked to DNA double-strand break repair defects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 10.1073/pnas.1818415116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Morales Y, Caceres T, May K, Hevel JM. Biochemistry and regulation of the protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs) Arch Biochem Biophys. 2016;590:138–152. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira MC, Barbot C, Tachi N, Kozuka N, Uchida E, Gibson T, Mendonça P, Costa M, Barros J, Yanagisawa T, Watanabe M, Ikeda Y, Aoki M, Nagata T, Coutinho P, Sequeiros J, Koenig M. The gene mutated in ataxia-ocular apraxia 1 encodes the new HIT/Zn-finger protein aprataxin. Nat Genet. 2001;29(2):189–193. doi: 10.1038/ng1001-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris M, Knudsen GM, Maeda S, Trinidad JC, Ioanoviciu A, Burlingame AL, Mucke L. Tau post-translational modifications in wild-type and human amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(8):1183–1189. doi: 10.1038/nn.4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]