Abstract

Introduction

A generous exposure of the midface region is essential for a comprehensive and thorough execution of midface surgical procedures, especially bilateral procedures. Traditional approaches to the midface the midface like the lateral rhinotomy and Weber–Fergusson/Dieffenbach incision with their modifications leave a visible scar, and they are limited in their unilateral exposure. The midface degloving approach with its exclusive intranasal and intraoral incisions leaves no external scars and lends excellent bilateral exposure of the maxilla, zygoma, paranasal areas and infraorbital margins from one side to the other. The midface degloving approach is mainly used to expose pathologies of the maxilla, nasal cavities, paranasal sinuses, nasopharynx, and the central compartment of the anterior and middle cranial base. This approach can also be used to treat midface trauma and perform high-level osteotomies.

Materials and Methods

We describe the midface degloving procedure for nine cases operated in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery over a period of 7 years (2012–2018): seven maxillary tumors and two maxillary cysts.

Results

We obtained excellent exposure for all the cases using this approach. Complications included mild distortion of the lower lateral nasal cartilages and oro-nasal communication.

Conclusion

The midface degloving approach lends excellent surgical access to the midfacial skeleton including the maxilla, the paranasal areas, the maxillary sinus, the zygoma, and infraorbital rims. The advantages of this approach besides its generous exposure, is the excellent cosmesis it provides leaving no external scars.

Keywords: Midface degloving, Midfacial degloving, Maxillary tumors

Introduction

A generous exposure of the midface region is imperative for a comprehensive and thorough execution of midface surgical procedures, especially bilateral procedures. This includes, surgery for maxillary benign and malignant tumors, large cyst enucleations, high-level midface osteotomies, and surgery for extensive midface trauma.

The traditionally-employed approaches to access midface pathologies include, the lateral rhinotomy and Weber–Fergusson/Dieffenbach incisions along with their modifications. However, the main disadvantage with these approaches is a visible residual facial scar and the limited unilateral exposure. The palatal approach, albeit does not leave an extra-oral scar, is quite limited in its surgical exposure. The degloving approach to the midface can be utilized to enhance exposure provided by the conventional maxillary vestibular approach by dissecting through the external nasal skeleton. The midface degloving approach, therefore, combines the maxillary vestibular incision with endonasal incisions. This approach with its exclusive intranasal and intraoral incisions leaves no external scars. Thereby, the cosmesis provided is excellent and it lends excellent bilateral exposure of the maxilla, zygoma, paranasal areas, and infraorbital rims from one side to the other.

The midface degloving approach is usually employed to expose and treat tumors of the nasal cavities, paranasal sinuses, nasopharynx, orbits, and the central compartment of the anterior and middle cranial base. This approach can be used to treat a variety of neoplastic, vascular, and odontogenic lesions [1]. The use of the midface degloving approach for midface trauma and osteotomies has also been reported [2, 3].

Materials and Methods

We describe the midface degloving approach for 9 cases operated in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery over a period of 7 years (2012–2018): seven maxillary tumors (two ameloblastoma, two keratocystic odontogenic tumors, one squamous cell carcinoma of antrum, one low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma, and one fibrous dysplasia) and two maxillary cysts (one radicular and one mucous retention cyst of antrum) (Table 1). The surgical protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of our Institute, and written informed consent was obtained for all patients included in this series.

Table 1.

List of cases operated using the midface degloving approach

| Patient | Age/sex | Pathology | Procedure | Complication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 42/F | Ameloblastoma | Partial maxillectomy | |

| 2. | 37/M | Ameloblastoma | Partial maxillectomy | |

| 3. | 21/M | Keratocystic odontogenic tumor | Enucleation + ostectomy | |

| 4. | 19/M | Keratocystic odontogenic tumor | Enucleation + ostectomy | |

| 5. | 55/M | Squamous cell carcinoma | Subtotal maxillectomy | Oro-nasal communication |

| 6. | 38/F | Mucoepidermoid carcinoma | Subtotal maxillectomy | |

| 7. | 22/M | Fibrous dysplasia | Surgical debulking | |

| 8. | 17/M | Mucous retention cyst of antrum | Cyst enucleation | Mild lower lateral nasal cartilage distortion |

| 9. | 27/M | Radicular cyst | Cyst enucleation |

Surgical Technique

The midface degloving approach was performed for all patients under general oral endotracheal anesthesia. Lidocaine 2% with adrenaline 1:80,000 was infiltrated into the highly vascularized maxillary vestibular intercartilaginous area and columella to reduce the amount of bleeding during incision and dissection. The procedure was performed with a maxillary vestibular incision and three intranasal incisions that included (1) bilateral intercartilaginous, (2) complete transfixion, and (3) bilateral piriform aperture incision. The intercartilaginous incision divides the junction between the upper and lower lateral cartilages. The lower lateral cartilage will eventually be displaced superiorly during the degloving procedure, whereas the upper lateral cartilage will remain attached to the midface skeleton [4].

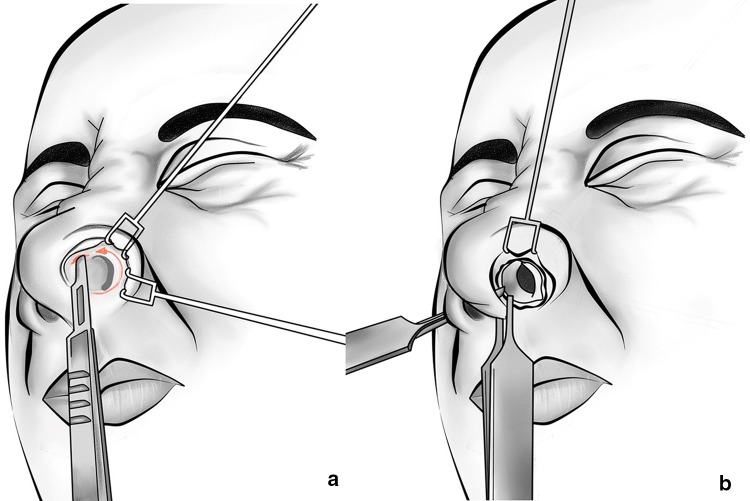

The ala of the nose was retracted with a double-skin hook, which helps to identify the scroll area. By using a two-prong retractor, the caudal margin of the nostril can be everted, and by applying digital pressure with the middle finger of the nondominant hand, a gap will be revealed between the caudal margin of the upper lateral and the cephalic margin of the lower lateral cartilages. With a scalpel, the intercartilaginous incision was made in this location. The incision and dissection were carried out with the lower lateral cartilage elevated, leaving the inferior edge of the upper lateral cartilage protruding into the vestibule. The incision was commenced along the inferior border of the upper lateral cartilage beginning at the lateral end and extending medially, curved into the membranous septum anterior to meet transfixion incision (Fig. 1a). Laterally, the incision must be sufficient enough so that it extends to the piriform aperture. A complete transfixion incision was made to separate the membranous septum/columella from the cartilaginous septum. An incision made along the caudal border of the septal cartilage from the medial end of the intercartilaginous incision toward the anterior spine is most effectively accomplished with a scalpel. A toothed Adson forceps can be used to grasp the columella right behind the caudal septum to avoid inadvertent transection of the medial crura (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

a An intercartilaginous incision is initiated at the inferior border of the upper lateral cartilage, beginning at the lateral end and extending medially curved into the membranous septum anteriorly to meet the transfixion incision. b A complete transfixion incision is used to separate the membranous septum/columella from the cartilaginous septum and converges with the intercartilaginous incision

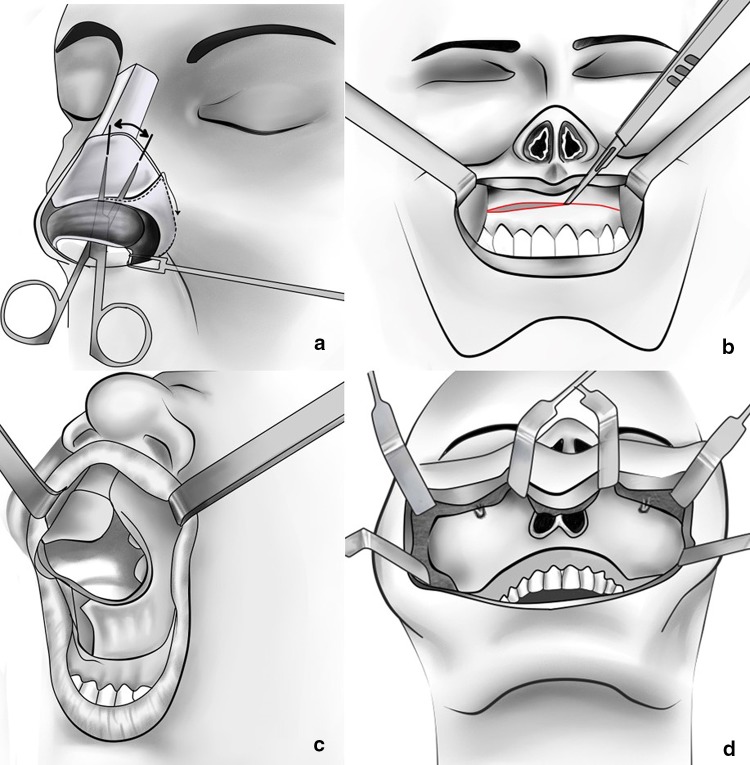

The bilateral piriform aperture incision was made with a full-thickness incision down through to the periosteum of the piriform margin and the nasal floor, which completes the circumvestibular release. Alternatively, this incision can be made through the nasal mucosa after the maxillary vestibular incision has been made. Dissection through the intercartilaginous incision allows access to the nasal dorsum and bones. Sharp subperichondrial dissection with a scalpel or a blunt dissection with scissors frees the soft tissues above the upper lateral cartilage as in a standard open rhinoplasty. The dissection should be within the subperichondrium plane to prevent injury to the overlying musculature and blood vessels of the nose. The elevation extends laterally to the nasomaxillary sutures and superiorly to the glabella. Retraction of the freed soft tissues allows sharp incisions to be made with a scalpel or with sharp periosteal elevators through the periosteum at the inferior edge of the nasal bones. Elevation of the soft tissue laterally to the piriform aperture was also performed, so that when a maxillary vestibular dissection is made, it would be easily connected to this pocket (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

a Dissection through the intercartilaginous incision allows access to the nasal dorsum and releases soft tissue from the underlying bony structures. b A standard sublabial incision in the maxillary vestibule is made approximately 3–5 mm superior to the mucogingival junction. c The periosteum along with the facial soft tissue envelope and the lower lateral nasal cartilages can then be degloved or ‘peeled off’ over the underlying nasal structures. d Exposure of the entire midfacial skeleton from one zygoma to the other to expose the infraorbital rims, the anterior maxilla, zygomatic buttress, and the piriform aperture

The standard maxillary vestibular incision was made approximately 5 mm superior to the mucogingival junction, leaving a cuff of free mucosa on the alveolus which facilitates closure. The incision extends as far posteriorly as necessary to provide exposure; however, the incision typically extends from the first molar to the contralateral first molar around the maxillary tuberosity down to periosteum (Fig. 2b). Periosteal elevators were used to elevate the tissues in the subperiosteal plane first over the anterior maxilla, and then extended widely to encompass posterior tissues behind the zygomaticomaxillary buttress. The infraorbital neurovascular bundle was identified superiorly and should be preserved unless involved in malignancy. Dissection medially and laterally facilitates its preservation. Subperiosteal dissection along the piriform aperture strips the attachments of the nasal labial musculature to allow its complete release from the midface skeleton. As the elevation continued, the entire midfacial soft tissue was separated from the maxilla and the nasal pyramid. The flap also includes the lower lateral cartilages and the columella (Fig. 2c). The entire midface including the maxilla, paranasal areas, infraorbital rims, zygomatic buttress, and the zygoma can easily be exposed, but reaching the zygomatic arch necessitates detachment of the some of the masseter muscle attachment (Fig. 2d). Depending upon the needs of the surgical procedure, additional exposure to deeper structures can be attained by midface osteotomies. The nasal pyramid can be removed to provide enhanced access to the nasofrontal duct and/or cribriform plate. The anterior maxilla can be removed to expose the maxillary and/or ethmoid sinuses. Segmental and/or complete LeFort osteotomies can also be performed to facilitate access to the central cranial base via this approach.

Restitution of the soft tissue of the face is paramount to limit cosmetic and/or functional deficits. If the medial canthal tendons were removed during surgery, they must be carefully reattached to the frontal process of the maxilla and lacrimal bone. The soft tissues were then redraped and the nasal tip brought back into position. The precise placement of the transfixion sutures is critical in determining the final position of the nasal tip and to prevent vestibular stenosis. The intranasal incisions were closed with 4.0 resorbable sutures. The maxillary vestibule was closed after properly reapproximating the nasolabial musculature, resetting the alar base, eversion of the vermillion, and finally closure of the oral mucosa. The nasal cavity was packed with Merocel nasal tampon for a day to prevent any nasal bleeds.

Results

We obtained generous exposure in all cases for adequate visualization and complete surgical removal of the pathologies. Figures 3a–d and 4a–d show a maxillary ameloblastoma and a mucous retention cyst of the antrum, respectively. One of the cases (mucous retention cyst of right antrum) had a mild residual deformity of the right lower lateral nasal cartilages (Fig. 4d). Residual oro-nasal communication was encountered with this approach in our patient treated for squamous cell carcinoma of antrum.

Fig. 3.

a and b CT showing the tumor involving the entire left maxillary sinus causing expansion and erosion of the anterior maxilla and alveolar process. c Intraoperative exposure for tumor resection. d Postoperative clinical appearance

Fig. 4.

a, b CT showing expansile cystic lesion involving the right maxillary sinus. c Intraoperative exposure for cyst enucleation. d Postoperative clinical appearance showing mild distortion of the right lower lateral nasal cartilages

Discussion

The first documented procedure performed via a facial degloving approach was a maxillectomy reported by Portmann and Retrouvey [5] in 1927. In 1974, Casson, Bonnano and Converse [6] published a series of cases employing the midface degloving approach, as described in its present technique.

Traditional approaches, such as Weber–Fergusson, Dieffenbach, or lateral rhinotomy, are easy to perform but result in facial scars and possible epiphora. These approaches may be associated with disfigurement of the face such as upward contracture of the ala and deviation of the nose, asymmetry of the upper lip and nasolabial groove, and medial canthal deformity [7]. Moreover, these approaches permit only unilateral exposure. The main advantage of the midface degloving approach over the traditional approaches is the combination of wide exposure, avoidance of facial incisions and scars, and facilitating bilateral exposure. The palatal approach does not leave an extra-oral scar but is limited in its surgical exposure and prone to palatal dysfunction. A summary of the varous approaches to the midface with respect to cosmesis, exposure, complications, and modifications is outlined in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of comparison of incisions and approaches to the midface/maxilla

| Midface degloving | Lateral rhinotomy | Weber–Fergusson/ Dieffenbach | Palatal approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| External scar | |||

| No external scar | External scar present | External scar present | No external scar |

| Exposure | |||

| Generous bilateral exposure of the midface | Limited unilateral exposure of the paranasal area | Extensive exposure of the midface but unilateral | Limited intraoral access to maxillary sinus and nasal cavity |

| Complications | |||

| Distortion of the lower lateral nasal cartilages | Possible upward contracture of the ala and deviation of the nose | Asymmetry of the upper lip and nasolabial groove | Palatal dysfunction |

| Modifications/ extensions | |||

| Can be combined with osteotomies of the midface for surgical access to the central cranial base | |||

Indications for the midface degloving approach include surgical access for a wide variety of benign maxillary or sinonasal conditions, such as ameloblastoma, inverted papilloma, angiofibroma, and various odontogenic or nonodontogenic cysts. Particularly advantageous is the use of this technique in the management of locally aggressive, histologically benign lesions such as odontogenic keratocyst, ameloblastoma, juvenile angiofibroma, and inverted papilloma, where a wide exposure is necessary to achieve a complete removal without facial incisions [8–11]. When combined with orbital incisions, such as the transconjunctival approach, wide exposure for an aggressive resection can be obtained with excellent cosmesis in the postoperative period [12]. Malignant tumors can also be treated with an en-bloc resection using this approach.

However, the operative feasibility of this procedure in sinonasal malignancy is relatively limited. Howard and Lund [10, 11] stated that the use of this technique should only be attempted in selected cases that can be successfully encompassed by the exposure. The midface degloving approach should therefore be indicated for small and slow-growing salivary gland malignancies (i.e., low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma, low-grade polymorphous adenocarcinoma, acinic cell carcinoma) and other malignant tumors where safe clean margins can be ensured [13].

Of late, neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy have gained acceptance in clinical oncology of head and neck cancer to reduce patient morbidity caused by major ablative surgery [14–17]. The midface degloving procedure can therefore be considered a viable option for patients post-chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy owing to its excellent vascularity and hence less likelihood for flap necrosis [10, 11]. The midfacial degloving technique will increasingly become popular in future as a preferred approach for midface oncologic surgery, where indicated [7].

Baumann and Ewers [2] used the midface degloving approach in 14 patients to correct post-traumatic deformities of the midface including deformities in the naso-orbito-ethmoid region corrected by orbitonasal osteotomy, telecanthus correction, orbital and nasal grafting, and zygomatic osteotomies for orbitozygomatic deformity.

Parameswaran et al. [3] operated on 9 patients using the midface degloving approach for extended osteotomies of the midface including LeFort 3 osteotomy for Crouzon Syndrome, Kufner quadrangular LeFort I osteotomy for advancement of the midface and the infraorbital complex en-bloc, and midface distraction at a modified LeFort 2 level for a secondary cleft deformity.

The midface degloving approach can be combined with osteotomies of the facial bones for surgical access to tumors of the central cranial base. A nasomaxillary osteotomy consisting of a transverse osteotomy of the nasal bone near the frontonasal suture, an infraorbital osteotomy medial to the nasolacrimal fossa, and a vertical osteotomy medial to the infraorbital foramen can be combined with a Le Fort I osteotomy pedicled on the cartilaginous septum to approach the central cranial base. This then essentially becomes a LeFort II osteotomy and provides excellent access to the lower clivus and upper cervical spine via a submucosal route without opening of the oropharyngeal mucosa [18].

A modification of the midface degloving approach was proposed by Krasue and Jafek [19], where bilateral nasal osteotomies and a septal transection was performed, thereby enabling the upper lateral cartilages and nasal bones to be retracted superiorly. In their technique, the anterior nasal spine along with a 1-cm anterior portion of maxillary crest was separated off the maxilla with a chisel. Heavy turbinate scissors were then used to transect the septal cartilage and overlying mucosa from 1 cm posterior to the anterior caudal edge of the septal cartilage all the way to the nasion. Lateral nasal osteotomies were made bilaterally in the usual fashion as for a rhinoplasty. The mucosa of the lateral nasal wall was cut with Metzenbaum scissors bilaterally, thereby releasing the final attachment of the nasal bones and upper and lower lateral cartilages from the midface. This modification allowed for better visualization of the nasal cavities and nasopharynx in general, as well as superior exposure of the nasofrontal duct and the cribriform plate area specifically.

The complications associated with the midface degloving approach are nasal cartilage distortion, nasal vestibule stenosis, oro-nasal communication, and injury to the infraorbital nerve. The nasal complications can be avoided by careful dissection around the cartilages and meticulous re-approximation of the nasal mucosa. A water-tight layered closure of the vestibular incision minimizes any sinus-related complications. Despite excessive undermining of the midfacial region, the patients in our series who underwent the midfacial degloving procedure showed excellent cosmetic results without sagging of tissue, deviation of the nose, or flattened alae. Stenosis of the nose is often considered to be a disadvantage of the midfacial, degloving procedure; however, this complication can be avoided if the nasal incisions are precisely sutured [20].

Conclusion

In conclusion, the midface degloving approach lends excellent bilateral surgical access to the midfacial skeleton including the maxilla, maxillary sinus, the paranasal areas, the zygoma, and infraorbital rims for tumor resection, cyst enucleation, midface osteotomies, and surgery for midface trauma. The main advantage of this approach besides its generous exposure is the excellent cosmesis it provides, leaving no external scars. The midface degloving must be included in the operative armamentarium of every head and neck surgeon for surgical access to the maxillary, nasal, sinonasal, paranasal, nasopharyngeal, and central skull base regions.

Acknowledgements

Line diagrams: courtesy of Dr Vidya Devi, MDS (OMFS). E-mail: vidya.devi.vuyyuru@gmail.com.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the individual participant included in the study. Additional informed consent was obtained from the individual participant for whom identifying information is included in this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Har-El G. Medial Maxillectomy via midfacial degloving approach. Oper Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;10(2):82–86. doi: 10.1016/S1043-1810(99)80024-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumann A, Ewers R. Midfacial degloving: an alternative approach for traumatic corrections in the midface. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;30(4):272–277. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2001.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parameswaran A, Jayakumar NK, Ramanathan M, et al. Mid-face degloving: an alternate approach to extended osteotomies of the midface. J Craniofac Surg. 2017;28(1):245–247. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaber JJ, Ruggiero F, Zender CA. Facial degloving approach to the midface. Oper Tech in Otolaryngol. 2010;21(3):171–174. doi: 10.1016/j.otot.2010.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Price JC, Holliday MJ, Johns ME, et al. The versatile midface degloving approach. Larynoscope. 1988;98(3):291–295. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198803000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casson PR, Bonnano PC, Converse JM. The midface degloving procedure. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1974;53(1):102–103. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197401000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitagawa Y, Baur D, King S, Helman JI. The role of midfacial degloving approach for maxillary cysts and tumors. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61(12):1418–1422. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2002.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maniglia AJ. Indications and techniques of midfacial degloving: a 15-year experience. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1986;112(7):750–752. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1986.03780070062013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maniglia AJ, Phillips DA. Midfacial degloving for the management of nasal, sinus, and skull-base neoplasms. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1995;28(6):1127–1143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howard DJ, Lund VJ. The midfacial degloving approach to sinonasal disease. J Laryngol Otol. 1992;106(12):1059–1062. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100121759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howard DJ, Lund VJ. The role of midfacial degloving in modern rhinological practice. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113(10):885–887. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100145505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Browne JD. The midfacial degloving procedure for nasal, sinus, and nasopharyngeal tumors. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2001;34(6):1095–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0030-6665(05)70368-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helman JI. Maxillectomy. Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1997;5(2):75–89. doi: 10.1016/S1061-3315(18)30084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adelstein DJ, Kalish LA, Adams GL, et al. An eastern cooperative oncology group pilot study: concurrent radiation therapy and chemotherapy for locally unresectable squamous cell head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(11):2136–2142. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.11.2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dragovic J, Doyle TJ, Tilchen EJ, et al. Accelerated fractionation radiotherapy and concomitant chemotherapy in patients with stage IV inoperable head and neck cancer. Cancer. 1995;76(9):1655–1661. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951101)76:9<1655::AID-CNCR2820760923>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benasso M, Corvo R, Numico G, et al. Concomitant administration of two standard regimens of chemotherapy and radiotherapy in advanced squamous carcinoma of the head and neck: a feasibility study. Anticancer Res. 1995;15(6B):2651–2654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitagawa Y, Sadato N, Azuma H, et al. FDG PET to evaluate combined intra-arterial chemotherapy and radiotherapy for head and neck neoplasms. J Nucl Med. 1999;40(7):1132–1137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kyoshima K, Matsuo K, Kushima H, et al. Degloving transfacial approach with Le Fort I and nasomaxillary osteotomies: alternative transfacial approach. Neurosurgery. 2002;50(4):813–820. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200204000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krause GE, Jafek BW. A modification of the midface degloving technique. Laryngoscope. 1999;109(11):1781–1784. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199911000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang SJ, Choi JW, Chung YS, et al. Midfacial degloving approach for resectioning and reconstruction of extensive maxillary fibrous dysplasia. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23(6):1658–1661. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31826460fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]