Abstract

Objective

To retrospectively study the cases diagnosed with osteomyelitis of jaw in AMC Dental Hospital.

Study Design

A total of 27 cases of osteomyelitis of jaw were analysed retrospectively from 2014 to 2018 at Department of oral and maxillofacial surgery, AMC Dental Hospital, Ahmedabad, India.

Result

Totally 27 cases of osteomyelitis were noted; 12 (44.44%) patients had involvement of maxilla, and 15 (55.55%) patients had involvement of the mandible. Twenty-one patients had underlying systemic disease, and 13 patients had history of substance abuse. The underlying aetiology in 20 patients was found due to odontogenic cause. There were only 3 patients having osteomyelitis without any underlying disease or any other predisposing factors.

Conclusion

Incidence of osteomyelitis and its outcome in the present study led to a better understanding of the aetiologic factors and its treatment. The results hypothesized a substantial correlation for onset of osteomyelitis with the underlying medical conditions and substance abuse. There was a higher correlation found between comorbid conditions and osteomyelitis of maxilla. Thorough study of the treatment revealed that conventional treatment plan is adequate for treating cases of osteomyelitis if the associated medical problem is also simultaneously treated and given due importance.

Keywords: Osteomyelitis, Jaws, Immunocompromised condition, Substance abuse

Introduction

Osteomyelitis is defined as an inflammation of medullary portion of bone or bone marrow or cancellous bone [1]. It may also be considered as an inflammatory condition of bone that usually begins as an infection of the medullary cavity, rapidly involving haversian systems, and quickly extends to the periosteum of the area. Osteomyelitis is truly an infection of bone [1–5].

Osteomyelitis was a common disease before the advent of the antibiotic era, but after the discovery of antibiotics and antimicrobial chemotherapeutic agents, the occurrence has significantly reduced. Recent studies show an increase in the incidence of osteomyelitis [3, 4]. Osteomyelitis is more frequently found in mandible and predominant in men along with a wide range of age [5].

Local and systemic host factors are important in the pathogenesis of osteomyelitis. These factors tend to compromise the immune system of an individual, and this immunocompromised state of patient eventually might contribute to osteomyelitis [6]. It is hypothesized through this study that a well-controlled systemic condition might evert the progress of osteomyelitis compared to an uncontrolled one.

The present study is reported with the following aims:

to create awareness that a high index of suspicion should be kept in mind in immunocompromised patients presenting with exposed bone in oral cavity;

to emphasize the need for early diagnosis and prompt and aggressive surgical management and institution of appropriate chemotherapy to ensure a favourable outcome;

to study the clinical presentation of osteomyelitis due to various causative agents.

Materials and Methods

The complete documented medical records and radiographs were audited and studied retrospectively by the authors for analysis of patients’ details and various variables. A total of 186 patients were admitted in Oral and maxillofacial surgery department at AMC Dental hospital, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India, for oro-facial infections in period of 4 years from 2014 to 2018. Out of that, there were 27 cases of osteomyelitis of jaw which were diagnosed and treated. Retrospective data were obtained for these 27 patients and studied thoroughly with the data including age, sex, anatomical area, aetiology, clinical features, associated systemic conditions, histopathological report, treatment given, days for antibiotic therapy, follow-up and complications encountered. Prior permission was taken from institutional ethics committee for the study.

Results

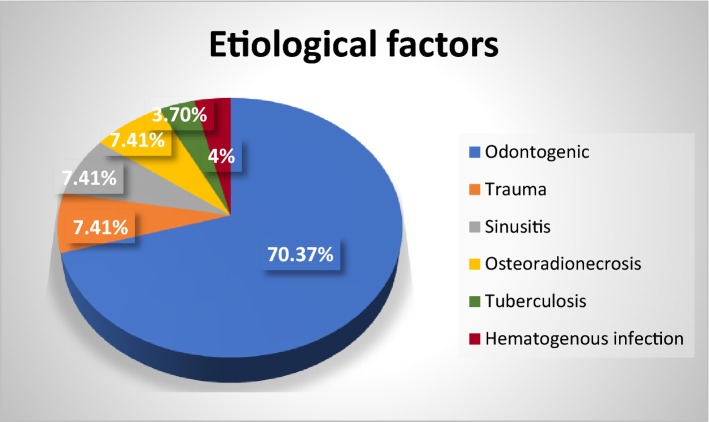

In the present study of total 27 patients, there were 12 cases (44.44%) of osteomyelitis of maxilla and 15 cases (55.55%) of mandibular osteomyelitis. There were 21 male and 6 female patients, and male/female ratio was found to be 7:2. The patients’ age ranged from 15 to 76 years with mean age of 53 years. The study showed varied results for aetiologic factors of osteomyelitis cases. The most common factor was found to be odontogenic (70.37%), and other factors were trauma (7.41%), post-radiation (7.41%), sinusitis (7.41%), tuberculosis (3.70%) and haematogenous infection (4%) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Aetiology of osteomyelitis

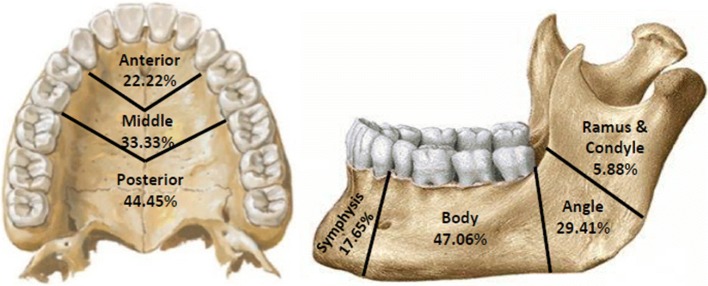

The data for affected anatomic site were also analysed (Table 1). The result showed higher incidence of osteomyelitis on the left side of face. The occurrence of osteomyelitis on the left side was in 55.55% of cases, that on the right side was in 25.92% cases, and 18.52% cases were found to be in midline. Distribution of osteomyelitis was further analysed by locus. It showed higher incidence of disease in posterior region in maxilla and body region in mandible (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Clinical findings, diagnosis, treatment and post-operative review

| Patients | Region | Aetiology | Medical status/predisposing factors | Diagnosis | Microorganism growth | Days of antibiotics | Post-operative complication | Treatment and rehabilitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | Right ant., middle and Post maxillary region | Odontogenic | Exanthemata, diabetes and hypertension | Chronic non-suppurative diffused sclerosing osteomyelitis | No growth | 9 days | None | Debridement, curettage, sequestrectomy, extraction |

| Patient 2 | Left mandibular body region | Odontogenic |

Rheumatic arthritis Tobacco chewing since 10 years |

Chronic suppurative osteomyelitis | No growth | 8 days | None | Deep debridement and curettage |

| Patient 3 | Left ant., middle and post-maxillary region | Haematogenous infection due to Bee sting | Diabetes and hypertension | Chronic non-suppurative diffused sclerosing osteomyelitis | No growth | 10 days | None | Debridement, curettage, sequestrectomy, extraction, acrylic splint |

| Patient 4 | Right post-maxillary region | Odontogenic | Malnutrition, hypertension and rheumatic arthritis | Chronic suppurative osteomyelitis | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 8 days | None | Debridement, curettage, sequestrectomy, acrylic splint |

| Patient 5 | Left mandibular body region | Odontogenic |

Diabetes Bidi smoking |

Chronic suppurative osteomyelitis | No growth | 7 days | Persistent pus discharge | Debridement, curettage and trans osseous wiring of pathological fracture followed by removal of infected hardware after 1.5 year |

| Patient 6 | Left middle and post-maxillary region | Odontogenic |

Iron deficiency anaemia, low serum calcium level and low PTH levels Masala chewing habit since 10 years |

Chronic suppurative osteomyelitis | No growth | 20 days | None |

Debridement, curettage, sequestrectomy, surgical removal of multiple impacted teeth, acrylic splint Followed by removable partial denture |

| Patient 7 | Right Mandibular body and angle region | ORN |

Ca. Oropharynx and hypertension Bidi smoking, alcoholism and masala chewing |

Radiation Osteomyelitis | No growth | 11 days | None | Debridement, curettage, sequestrectomy |

| Patient 8 | Left middle maxillary region | Left max. Sinusitis | Masala chewing and Bidi smoking since 20 years | Chronic suppurative osteomyelitis with fungal infection | Pseudomonas aeruginosa + Mucormycosis | 17 days | Paraesthesia and Recurrence | Surgical excision of necrotic bone and, extraction followed by sequestrectomy on recurrence after 4 months and antifungal medications |

| Patient 9 | Left post-maxillary region | Odontogenic |

Rheumatic arthritis and malnutrition Smoking since 40 years |

Chronic non-suppurative diffused sclerosing osteomyelitis | No growth | 10 days | Wound dehiscence | Debridement, curettage, decortication, sequestrectomy |

| Patient 10 | Left mandibular angle region | Trauma | None | Chronic suppurative osteomyelitis | No growth | 8 days | None | Debridement, curettage, sequestrectomy followed by 2.5 mm titanium plate fixation |

| Patient 11 | Left post-maxillary region | Odontogenic | None | Chronic suppurative osteomyelitis | No growth | 8 days | None | Debridement, curettage, saucerization of necrotic bone, extraction |

| Patient 12 | Right mandibular body region | Odontogenic |

Diabetes and asthma Bidi smoking since 30 years |

Chronic suppurative osteomyelitis | Gram-negative Bacilli, E. coli | 7 days | None | Extraoral curettage and debridement, acrylic splint |

| Patient 13 | Right mandibular body and angle region | ORN |

Ca. Left tonsillar region Alcoholism since 10 years |

Radiation osteomyelitis | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 9 days | None | Debridement, curettage, sequestrectomy, extraction |

| Patient 14 | Right mandibular body region | Odontogenic |

Diabetes Tobacco and betel nut chewing since 20 years |

Chronic suppurative osteomyelitis | No growth | 8 days | None | Segmental resection, acrylic splint |

| Patient 15 | Left mandibular body region | Odontogenic | None | Chronic suppurative osteomyelitis | No growth | 8 days | None | Debridement, curettage, sequestrectomy, extraction |

| Patient 16 | Left mandibular angle region | Odontogenic |

Diabetes and hypertension Smoking since 30 years |

Chronic non-suppurative diffused sclerosing osteomyelitis | No growth | 7 days | None | Debridement, curettage, sequestrectomy |

| Patient 17 | Mandibular symphysis region | Odontogenic | None | Acute suppurative osteomyelitis | No growth | 10 days | None |

Debridement, curettage, sequestrectomy, acrylic splint followed by RPD |

| Patient 18 | Left middle and post-maxillary region | Odontogenic | Diabetes and hypertension | Actinomycotic osteomyelitis | Actinomycosis | 7 days | None | Debridement, curettage, sequestrectomy |

| Patient 19 | Midline of palate including premaxillary region and infra orbital region of right side | Odontogenic and pansinusitis |

Diabetes Alcoholism since 35 years Bidi smoking since 40 years |

Chronic non-suppurative diffused sclerosing osteomyelitis with fungal infection | Mucormycosis | 22 days | Paraesthesia and change in nasal tone | Debridement, curettage, sequestrectomy, acrylic splint and antifungal medications |

| Patient 20 | Left mandibular angle region | Odontogenic |

Anaemia Tobacco chewing |

Acute suppurative osteomyelitis | No growth | 8 days | None | Debridement, curettage, extraction and peripheral ostectomy |

| Patient 21 | Left mandibular sigmoid and ramus region | Tuberculosis | Diabetes and TB | Specific infective osteomyelitis—tuberculous | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 15 days | None | Anti-Kochs treatment protocol was followed, and after that, sequestrectomy was done |

| Patient 22 | Mandibular symphysis region | Trauma | None | Chronic non-suppurative diffused sclerosing osteomyelitis | No growth | 10 days | Restriction in tongue movement and slight incompetency of lips | Debridement, curettage, sequestrectomy, extraction, removal of infected hardware followed by 2.5-mm titanium plate fixation |

| Patient 23 | Maxillary anterior region | Odontogenic |

Diabetes Bidi smoking Alcoholism |

Chronic suppurative osteomyelitis | Fungal hyphae, aspergillosis | 25 days | None | Debridement, curettage, sequestrectomy, extraction and antifungal medications |

| Patient 24 | Right mandibular body region | Odontogenic | Diabetes | Actinomycotic osteomyelitis | Actinomycosis | 12 days | None | Debridement, curettage, sequestrectomy, extraction |

| Patient 25 | Mandibular symphysis region | Odontogenic | Hypertension | Chronic non-suppurative diffuse sclerosing osteomyelitis | No growth | 8 days | Paraesthesia | Debridement, curettage, sequestrectomy |

| Patient 26 | Left maxillary middle region | Odontogenic | Diabetes | Chronic suppurative osteomyelitis | Enterococcus spp. | 21 days | None | Debridement, curettage, sequestrectomy, extraction, acrylic splint |

| Patient 27 | Left post-maxillary region | Odontogenic | Anaemia | Chronic non-suppurative diffuse sclerosing osteomyelitis | None | 8 days | None | Debridement, curettage, saucerization extraction |

Fig. 2.

Distribution of osteomyelitis by locus

The study showed the common chief complaints were pain (72%), exposed bone (68%), persistent pus discharge (48%) and swelling (35%). The other chief complaints included fracture, malocclusion, fever and trismus.

The data revealed significant correlation including various endocrinal diseases and substance abuse with occurrence of maxillofacial infection. These patients had various comorbidities as diabetes mellitus, malnutrition, alcoholism, smoking, tobacco chewing, anaemia, malignancy, hypertension, tuberculosis, arthritis, exanthemata, steroid use which might have led to immunocompromised state (Table 1). Among all 27 cases, 21 patients had underlying systemic disease (77.77%), 13 patients had history of substance abuse (48%), and only 3 patients (11.11%) were without any associated factors (Table 2). Of these 3 patients, 2 were adolescent males and other 1 female.

Table 2.

Predisposing factors in cases of osteomyelitis

| Factor | Maxillary | Mandibular | Total number | Total Percentage |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percentage | Number | Percentage | |||

| Diabetes | 6 | 50.00 | 6 | 40.00 | 12 | 44.44 |

| Smoking | 4 | 33.33 | 4 | 26.66 | 8 | 29.63 |

| Hypertension | 4 | 33.33 | 3 | 20.00 | 7 | 25.92 |

| Tobacco chewing | 2 | 16.66 | 4 | 26.66 | 6 | 22.22 |

| Alcohol | 2 | 16.66 | 2 | 13.33 | 4 | 14.81 |

| Anaemia | 2 | 16.66 | 1 | 6.66 | 3 | 11.11 |

| Arthritis | 2 | 16.66 | 1 | 6.66 | 3 | 11.11 |

| Malnutrition | 2 | 16.66 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 7.41 |

| Asthma | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6.66 | 1 | 3.70 |

| Post-radiation | 0 | 0 | 2 | 13.33 | 2 | 7.41 |

| Tuberculosis | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6.66 | 1 | 3.70 |

| Exanthemata | 1 | 8.33 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.70 |

| None | 1 | 8.33 | 2 | 13.33 | 3 | 11.11 |

The diagnosis was reached by evaluating the clinical examination, radiological investigations and histopathological results. There were 25 (92.59%) chronic cases and 2 (7.41%) acute cases. From 25 chronic cases, there were 12 cases (48%) of suppurative osteomyelitis and 13 cases of non-suppurative diffuse sclerosing osteomyelitis. There were three cases (11.11%) of osteomyelitis associated with mucormycosis in maxilla. There were two cases of actinomycotic osteomyelitis, two cases of post-trauma, two cases of post-radiation osteomyelitis and one case of tuberculous osteomyelitis (Table 1).

All the patients which were diagnosed with osteomyelitis were treated by a standard protocol followed in department. After the clinical examination and related radiological investigations, all the lesions were biopsied. All patients were given standard pre-operative empirical antibiotic regimen. In cases where pus discharge was persistent, the sample was sent for culture sensitivity and gram staining, and accordingly, the medications were changed if needed. The surgical management included extraction of associated teeth, curettage, sequestrectomy and decortication. In one patient (patient 25), there was pathological fracture present pre-operatively, so open reduction and fixation was done along with sequestrectomy. There was only one case of recurrence on 4-month follow-up which was then found to be associated with mucormycotic growth (patient 8). Three patients of mandibular osteomyelitis were given post-operative IML to prevent pathological fracture, due to thin bone left after the surgical curettage and decortication. Obturators and possible rehabilitation were done in all the cases.

The number of days for antibiotic management was analysed. It ranged from 7 to 25 days with mean of 11 days. Long-term antibiotic treatment was needed in all the cases. The standard antibiotic protocol followed in our unit is intravenous injections of amoxicillin + clavulanic acid or cefotaxime + metronidazole. In few cases, drugs were changed according to the culture sensitivity reports, when pus was persistent even after the empirical medical treatment. Gentamycin or amikacin was used in few cases for 5 days. Three patients who were diagnosed with osteomyelitis are associated with fungal growth (mucormycosis) in maxilla, and additional protocol was followed for antifungal medications. These patients were treated additionally with amphotericin B 50 mg. Fluconazole 400 mg was also advised orally for 6–8 weeks post-operatively after physicians consult.

Follow-up period ranged from 1 to 32 months with an average of 7.2 months. The result showed a wide variation in the follow-up between patients. During follow-up visits, all patients were examined clinically as well as radiographically. Out of 27 patients, 22 patients (77.77%) showed no signs of any complication. Two patients (7.41%) had complaint of paraesthesia. One patient had persistent pus discharge on 1-month follow-up, 1 patient had wound dehiscence, 1 had restriction of tongue movement and slight incompetency of lips, and 1 patient showed recurrence with re-exposed bone and pus discharge when follow-up examination was done after 4 months.

The patient with persistent pus discharge was readmitted and given IV antibiotics, and re-suturing was done in patient with wound dehiscence. One patient that showed recurrence on 4th month follow-up was re-biopsied and re-evaluated. Necessary systemic evaluation, culture sensitivity and microbial analysis were done which revealed the association of mucormycosis. That patient was re-operated, and antibiotics and amphotericin B medications were given.

Discussion

The term ‘osteomyelitis’ was introduced by Nelaton in 1844, and it is said to be truly an infection of bone and marrow [7]. Fungi, parasites and viruses affect the bone and marrow, but still osteomyelitis is found to be most commonly caused by bacterial infections. One might expect the incidence of osteomyelitis to increase along with the increased number of immunocompromised patients. So, further study related to causes, demographics, predisposing factors and management of this disease was carried out.

Osteomyelitis has traditionally been classified into three categories [8]. The categories were initially divided as haematogenous osteomyelitis, which will be a bone infection that has been seeded through the bloodstream. Further, it was osteomyelitis due to spread from a contiguous focus of infection without vascular insufficiency, is seen most often after trauma or surgery, and is caused by bacteria which gain access to bone by direct inoculation or extension to bone from adjacent contaminated soft tissue. Lastly, osteomyelitis is due to contiguous infection with vascular insufficiency. The change of organisms resistant to commonly used antibiotics, existence of more individuals who are medically compromised, lack of experience in managing the disease by many practitioners, and its varying manifestations when jaws are affected have made the effective management of osteomyelitis ever more difficult [1].

In our institute, male to female ratio was 3.5:1. These findings are comparable with other studies [4, 5] as the male to female predilection range is found vary up to 5.2:1 [3]. Male predominance is seen since they have higher habit of substance abuse as compared to females. The age ranged from 15 and 76 years. These findings are also similar with other studies where a uniform distribution of patients is seen across the various age groups [4, 5].

It is a well-established fact that osteomyelitis affects maxilla less frequently than mandible. The mandible/maxilla ratio in our study is found to be 5:4. It is reasoned with the presence of significant collateral blood flow in the midface and the porous nature of membranous maxillary bone [9]. Demographically, in our study, the infection is found more frequently in the mandible as compared to maxilla. Yet the results showed a surprising finding that our cases for osteomyelitis are maxilla were almost same as that in mandible. Higher involvement of body region in mandible and posterior region in maxillary osteomyelitis was found which is comparable to previous reports [4, 5].

Although osteomyelitis is a difficult disease to treat, certain conditions make it even more difficult to manage. Diabetes, radiotherapy, malnutrition, alcoholism and other substance abuse, anaemia, malignancy, hypertension, immunosuppression, multi-drug resistant tuberculosis are all comorbidities that interfere with wound healing and therefore make the treatment of osteomyelitis challenging. In our study, there were 24 patients of osteomyelitis with predisposing factors, out of which there were 8 patients who had underlying systemic disease but were unaware regarding the condition.

Studies have showed that contiguous infections like sinusitis and odontogenic infections have contributed to acute forms of osteomyelitis. In the present study, it was found that odontogenic infections were preceded by diabetes and smoking more (Table 2). Results also revealed that there was higher association of diabetes and other comorbid conditions with osteomyelitis in maxilla. Trauma too acts as a predisposing cause for chronic osteomyelitis. Chronic systemic disease, compromised host defences and alterations in the vascularity of bone are all factors that predispose patients to osteomyelitis [5].

Diabetes is a significant factor in the phenomenon of osteomyelitis of the jaw bones. A patient in our study had a history of a honey bee sting on the left side of face which got infected, and through haematological route, it spreads till left maxillary arch on the same side following to osteomyelitis in the same region within a period of 1 month (Table 1—patient 3). That patient had an uncontrolled diabetes. It is already a proven fact that patient with diabetes has an altered immune response to infection, as hyperglycaemia allows bacteria to replicate at an increased rate providing a suitable environment and contributes to defects in leucocyte function. These defects in their defence mechanism consist of defective chemotaxis and decreased bactericidal function. Defective antibody synthesis and decreased complement levels are the other abnormalities associated with diabetes that can affect the immune defences [10]. In our study, a strong correlation between diabetic status and the incidence of osteomyelitis among the diabetic patients was evident.

The incidence of tuberculosis is increased worldwide and so has its significance. Tuberculous involvement of mandibular condyle is the rarest one, and very few cases have been registered till now [11]. We had one case of tuberculous osteomyelitis in mandibular condyle and sigmoid region which is rare condition. Anaemia and malnutrition might also complicate the situation significantly by altering the host immune response of the patients to fight infections [6]. The post-radiation injury evolves in chronic hypovascularity and hypocellularity, and ultimately, hypoxemia leads to ischaemic necrosis [12]. Autoimmune process may also lead to endarteritis and vascular insufficiency which makes the person prone to osteomyelitis [13]. The vascular supply to infected bone has a major impact on its ability to heal. Poor blood flow acts as a host factor and makes it difficult for antimicrobial agents and host immune cells to access the bacteria [14]. Bone biopsy with histopathological examination and tissue culture is considered the gold standard for the diagnosing osteomyelitis [6]. Most of the studies have shown a mixed floral infection. Coviello and Stevens had concluded the result in their study: 93% of chronic osteomyelitis cases are polymicrobial [15]. The present study also showed infections of a mixed flora (aerobic and anaerobic) correlating with other studies.

The chronic condition of osteomyelitis is due to multiple factors. The infected area and sequestrum show ischaemic characteristics and relatively avascular condition due to which an area with reduced oxygen tension is produced which cannot be penetrated even by antibiotics. The diffusion rate of antibiotics into dead bone is so low that frequently it is impossible for the antibiotic to reach the nidus of infection in adequate manner, regardless of the antibiotic concentrations at the site of infection [16]. So, the treatment protocol consisted of a combination of surgery and antimicrobial treatment. The aim of surgery is to eliminate all infected and necrosed tissues, so a chance for reperfusion and drainage can be facilitated in the area of insult.

The underlying systemic conditions were treated, and patients were counselled for cessation of deleterious habits. Then, empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy was started. Various combinations of antibiotics were used as previously described. Gentamycin or amikacin was added when gram-negative organism was seen during culture sensitivity. Due to poor vascularity in cases of osteomyelitis, long-term antibiotic treatment is mandatory; the duration of post-operative antibiotics in patients was 7–25 days as listed in Table 1 and in contrast to the long-term antibiotic therapy the duration ranging from 30 to 195 days was recommended by other authors [3, 4].

After correcting underlying systemic condition, surgical intervention forms one of the mainstay treatments for the definitive management of osteomyelitis of jaws. It is intended at providing drainage to the area of infection, removal of sequestrum and other foreign bodies to provide new source of vascularity. It ranges from simple sequestrectomy, to segmental resection and reconstruction in refractory cases. In most of our cases, a conservative surgical treatment approach was used. Biopsy was done in few aggressive cases to rule out neoplastic lesion.

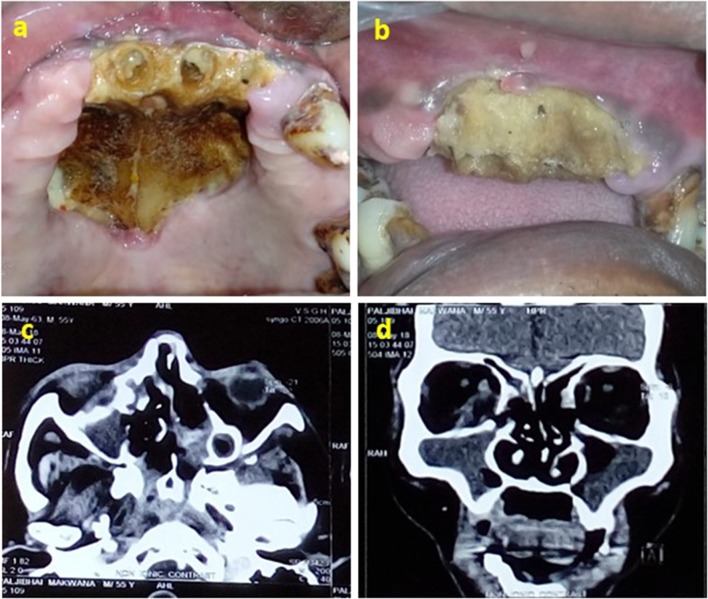

Fungal growth was seen in 3 patients having lesion in maxilla. When a fungal aetiology was discovered, an antifungal protocol was followed with amphotericin B and antifungal drugs (fluconazole) (Fig. 3). All patients showed satisfactory resolution of the condition in 4 weeks. Early intervention seems to provide a better prognosis and may be a key factor in avoiding ablative surgical procedures [17].

Fig. 3.

Clinical photograph—patient 19: a, b intra-oral picture of exposed dead bone in maxilla and on palate. c Axial view of CT scan showing erosion in right lamina papyracea and intra-orbital extension, abuts right optic nerve with focal loss of fat plane, d coronal view of CT scan showing pansinusitis and involvement of right orbit

The complication rate in our study was 22.22%, among which most common complication encountered was paraesthesia which was probably due to the proximity of the nerve to the infected site. One patient with post-trauma osteomyelitis showed restricted tongue movement and incompetent lips post-operatively. Although the condition was present as a complication after first surgery was done previously by another hospital (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Clinical photograph—patient 22: a, b intra-oral pre-operative view of sequestrum and exposed hardware on buccal and lingual side, c removed sequestrum, d fixation of pathological fracture with titanium plate

Conclusion

In this retrospective study, we conclude that there is a strong correlation of the immunocompromised status of the patients with the incidence of osteomyelitis of the jaws. Immunocompromised status of the patients poses challenges in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of osteomyelitis. Diabetes and smoking were the main predisposing factors in osteomyelitis according to our study which showed higher association with maxillary osteomyelitis. A high index of suspicion of possible osteomyelitis should be kept in mind in immunocompromised patients presenting with exposed bone. So, it is important to understand local and systemic conditions which can deteriorate the immune system and precede to a chronic bone infection. We should precisely examine signs and symptoms in the complex cases with multiple comorbidities and decide a firm diagnosis that leads to an exact treatment plan. Resolution of osteomyelitis of the jaws is majorly affected by correction of the underlying systemic contributing medical problems. Early diagnosis and prompt surgical intervention in the form of conservative resection of diseased bone with good margins and long-term antibiotics give better results in dealing with chronic osteomyelitis in immunocompromised patients.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ramita Sood, Email: dr.soodramita@gmail.com.

Mruga Gamit, Email: mrugagamit@gmail.com.

Naiya Shah, Email: naiya1993@gmail.com.

Yusra Mansuri, Email: yusramansuri@gmail.com.

Gaurav Naria, Email: gauravnaria@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Topazian RG, Goldberg MH, Hupp JR, editors. Oral and maxillofacial infections. 4. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 2002. pp. 214–242. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marx RE. Acute osteomyelitis of the jaws. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1991;3(2):367–381. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rangne A, Rudd A. Osteomyelitis of the jaws. Int J Oral Surg. 1978;7:523–527. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9785(78)80068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taher AAY. Osteomyelitis of the mandible in Tehran, Iran analysis of 88 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;76:28–31. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(93)90288-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koorbusch GF, Fotos P, Terhark-Goll K. Retrospective assessment of osteomyelitis: etiology, demographics, risk factors, and management in 35 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;74(2):149–154. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90373-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peravali RK, Jayade B, Joshi A, Shirganvi M, Bhasker Rao C, Gopal Krishnan K. Osteomyelitis of maxilla in poorly controlled diabetics in a rural Indian population. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2012;11(1):57–66. doi: 10.1007/s12663-011-0283-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelaton A. Elements de pathologie chirurgicale. Paris: Germer-Bailliere; 1844. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lew DP, Waldvogel FA. Osteomyelitis. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(14):999–1007. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704033361406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hudson JW. Osteomyelitis of Jaws: a 50-year perspective. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:1294–1301. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(10)80131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hannan CM. Special considerations in the management of osteomyelitis defects (diabetes, the ischemic or dysvascular bed, and irradiation) Semin Plast Surg. 2009;23(2):132–140. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheikh S, Pallagatti S, Gupta D, Mittal A. Tuberculous osteomyelitis of mandibular condyle: a diagnostic dilemma. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2012;41:169–174. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/56238546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koorbusch GF, Deatherage JR, Curé JK. How can we diagnose and treat osteomyelitis of the jaws as early as possible? Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2011;23:557–567. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gudmundsson T, Torkov P, Thygesen TH. Diagnosis and treatment of osteomyelitis of the jaw: a systematic review (2002–2015) of the literature. J Dent Oral Disord. 2017;3(4):1066. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fritz JM, McDonald JR. Osteomyelitis: approach to diagnosis and treatment. Phys Sportsmed. 2008;36(1):nihpa116823. doi: 10.3810/psm.2008.12.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coviello V, Stevens MR. Contemporary concepts in the treatment of chronic osteomyelitis. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2007;19:523–534. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eckardt JJ, Wirganowicz PZ, Mar T. An aggressive surgical approach to the management of chronic osteomyelitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;298:229–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krakowiak PA. Alveolar osteitis and osteomyelitis of the jaws. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2011;23:401–413. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]