Abstract

Background

Parotid gland and duct injuries are rare complications following surgery of parotid gland and temporomandibular joint. Sialocele is a cavity filled with saliva, usually formed as a result of trauma to salivary gland/duct or an iatrogenic complication of surgery. Several methods of managing parotid duct injury have been reported in the literature. In this article, we describe an indigenous way of internalisation of salivary fistula that resulted from traumatic injury to the parotid duct.

Methods

The authors present two cases of parotid sialocele managed using Foley’s catheter through an intraoral opening, and catheter was internalised, secured and left in situ for 15 days.

Results

The salivary flow was found to be normal through the intraoral opening, and no recurrence was observed postoperatively.

Conclusion

Parotid duct injury associated with sialocele and cutaneous salivary fistula could be effectively internalised using Foley’s catheter, under local anaesthesia. This technique of internalisation of parotid sialocele is simple, less invasive and may be performed as an outpatient procedure.

Keywords: Parotid duct, Sialocele, Fistula, Foley’s catheter, Internalisation

Introduction

Deep lacerations over the buccal area constitute one of the commonly observed maxillofacial injuries. Such lacerations make the regional vital structures such as a parotid duct, facial nerve branches and transverse facial artery vulnerable to injury [1].

Parotid duct injuries may be post-traumatic or iatrogenic. A continuous salivary secretion without proper drainage leads to extravasation of saliva that results in the formation of a cutaneous fistula. These fistulae are non-healing because of a continuous flow of saliva, infection and the presence of the foreign body. Quite frequently, these parotid fistulae result from penetrating injury to the parotid gland from sharp weapons or injury due to the shattered glass after a motor vehicle accident. The other causes can include malignancy, operative complications of parotid gland or rhytidectomy and infections of the parotid gland. Rarely, they occur as a congenital malformation during foetal development leading to the ectopic accessory parotid gland [2].

A parotid fistula is a communication between the skin and a salivary duct or gland, through which saliva is discharged. The opening site for fistula can be external at the retro-auricular region/skin over the facial cheek or internal through the oral mucosa. A parotid fistula is distressing to the patient because of a continuous dribble of saliva during mastication. Timely treatment is important since fistulae may result in wound dehiscence and infection of the buccal space.

Several cases of sialocele management have been reported in the literature. Here, we present two cases in which internalisation of sialocele with cutaneous fistula was managed indigenously with the use of urinary (Foley’s) catheter.

Review of Literature

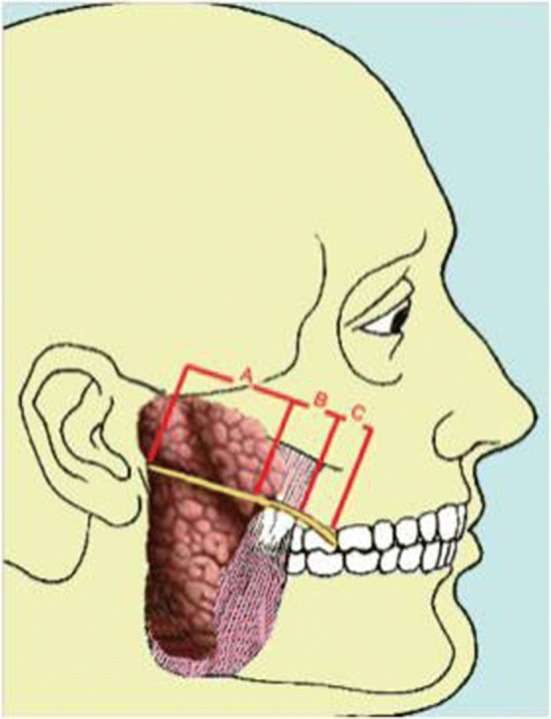

A classification of parotid injuries has been devised by Van Sickels [3] based on the anatomic location. This system divides the parotid injuries into the following: (1) posterior to the masseter or intra-glandular (site A), (2) overlying the masseter (site B) and (3) anterior to the masseter (site C) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Classification of parotid duct injury

The common clinical features of parotid injuries include salivary extravasations into the adjacent tissues causing swelling over or adjacent to parotid gland (sialocele), expanding neck mass and cutaneous fistula formation. In glandular fistulae, discharge is less and tends to heal spontaneously with conservative treatment, whereas ductal fistulae discharge saliva continuously, and hence, spontaneous healing is very rare.

The examination of such injuries should start from obtaining a history from the patient. When trauma to the salivary glands is suspected, the clinician should ask when the patient ate his last meal, because eating stimulates salivary gland function; and if the patient has had his last meal after the trauma, it is more probable to notice saliva oozing out of the wound. The next step in the physical examination of injuries should include an assessment of the location, size, shape, type (e.g. puncture, laceration, avulsion, crush, abrasion), asymmetry, drainage (i.e. quality, character, odour) tenderness, surrounding erythema, oedema, cellulitis, or crepitation and facial nerve status. A penetrating injury existing along a line joining the tragus of the ear and the mid-portion of the upper lip is likely to be associated with injury of the parotid gland, the parotid duct or both [4].

The most straightforward way to diagnose a parotid duct injury is to cannulate the intraoral parotid duct papilla with a small silastic tube and inject normal saline to check whether it appears extraorally. Methylene blue should not be used as it would contaminate the field [5]. In cases of cutaneous fistula diagnosed after a week, the ductal papilla would be obliterated. In such instances, ultrasonography and computed tomography would be helpful in diagnosing the sialocele or ductal injury. To reconfirm, the discharge can also be checked for salivary amylase level [6].

Case Report

Case I

A 43-year-old male patient reported with a laceration on the left side of the face following occupational injury with a saw. Computed tomography suggested a zygomaticomaxillary complex fracture. Under general anaesthesia, open reduction and internal fixation of the fracture were performed and exploration was done to locate the parotid duct. As the injury was caused by a saw, the duct could not be isolated and the wound was closed primarily. The parotid duct injury here was difficult to be classified, but it could be either A or B based on the site of the injury. Two weeks later, the patient presented with a complaint of fluid discharge during mastication. Ultrasonographic examination revealed a sialocele with an external fistula. Successive aspirations and compressive dressing were applied to the region for 5 days along with anti-sialogogue therapy (glycopyrrolate), with no clinical improvement.

The local anaesthetic solution was infiltrated around the fistula. A No 8 Foley’s catheter was inserted through the extraoral fistula under ultrasound guidance (Fig. 2). Once the position of the catheter was confirmed to be within the sialocele, the bulb of the catheter was inflated using normal saline. Intraorally, the inflated catheter was palpated and a puncture wound was made using no 11 BP blade, over the mucosa. Blunt dissection was done using a haemostat, and the bulb of the catheter was grabbed. The catheter was deflated and pulled out intraorally (Fig. 3). The remaining part of the catheter extraorally was severed, and ultrasound confirmed the position of the catheter as present within the sialocele. The catheter was secured intraorally using non-resorbable sutures thus establishing a new intraoral opening of the parotid duct. Extraorally, the fistula was de-epithelised and layerwise closure was done using 3′0 vicryl (Fig. 4). External pressure was applied over the parotid region for 2 days. The parotid gland was milked to check the flow of saliva intraorally. Antibiotics and analgesics were administered for 5 days postoperatively. The catheter was left in situ for 15 days and then removed. After its removal, normal salivary flow was observed through the newly formed ductal opening.

Fig. 2.

Ultrasound-guided insertion of Foley’s catheter through the fistula in case 1

Fig. 3.

Ultrasound image confirms the position of the catheter bulb in the sialocele in case 1

Fig. 4.

Secured catheter left in situ and sutured in case 1

Case II

A 25-year-old male patient reported with a laceration on the left side of face extending from the pre-auricular region to the chin, following a road traffic accident. Initial management consisted of debridement and suture of the wounds under local anaesthesia (Fig. 5). The patient was not willing for any other treatment including parotid duct repair. He was explained about the sequelae of parotid duct injury and was discharged against medical advice. Here, the parotid duct injury was found to be of type B. One week later, the patient presented with a complaint of fluid discharge during mastication. An ultrasound was performed which revealed the presence of a sialocele with an external fistula. Successive aspirations and compression dressing were applied to the region for 5 days, with no change in clinical findings. Once the resolution of the fistula was not achieved, internalisation of the salivary fistula was done using Foley’s catheter with the help of ultrasonography. The catheter was secured intraorally using non-resorbable sutures. Salivary flow was observed through the catheter. Fifteen days later, the catheter was removed, the gland was milked to check for patency of the duct and salivary flow was observed through it. The extraoral salivary leak was absent, and complete closure of skin was observed (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Pre- and intraoperative images of case 2

Fig. 6.

Postoperative image of healed fistula in case 2

Discussion

Facial trauma can cause significant aesthetic and functional impairment. Lacerations in the parotid–masseter region can cause damage to the facial nerve, the transverse artery of the face and parotid gland. Injury to the parotid duct occasionally causes accumulation of salivary secretion in the adjacent soft tissue leading to a phenomenon known as sialocele. Sialocele typically develops 8–14 days after injury [4, 7]. The first case mentioned in this article developed discharge of salivary fluid 2 weeks after facial trauma, and the second one presented with a similar complaint, a week after injury.

According to the classification proposed by Van Sickels, the treatment option for parotid sialocele varies according to the site of injury. Site A injury corresponds to the part of the duct which is located intra-glandular whose treatment involves only closure of the lacerated parotid capsule. No effort is made to anastomose the duct because these injuries have a lower complication rate and healing usually occurs fast and uneventfully [9]. When an injury in site B or C exists and both ductal ends are identified, they must be sutured together without tension.

Initially, a small silicone catheter or a probe is inserted through both ends and the stumps are brought together and sutured over the catheter to prevent suturing the anterior wall of one stump with the posterior wall of the other [6, 8].

There are various treatment options reported in the literature for management for parotid duct injuries which include aspiration and pressure dressings, anti-sialogogues, radiation therapy, Botox therapy, parasympathetic denervation (tympanic denervation), cauterisation of the fistulous, reconstruction of the duct, superficial or total parotidectomy [4, 6]. The first line of management of parotid duct injury is usually by a conservative approach using repeated aspirations and pressure dressings. Anti-sialogogues such as glycopyrrolate and propantheline bromide can also be used as adjuncts to control the flow of saliva [9–12]. However, this need not be effective in all patients. In cases where the conservative approach has failed, radiation therapy for the specific gland to induce fibrosis and stop the production of saliva is usually performed [13]. Botulinum toxin is a good alternative to radiation therapy. If the patient does not respond to such measures, invasive procedures such as denervation of the nerve supply to the gland, cauterisation of the fistula, superficial or total parotidectomy should be considered [11, 14, 15]. Finally, reconstruction of the duct by the end-to-end anastomosis using silastic tube cannulation is a very effective surgical method, though it must be done before the obliteration of the ductal papilla sets in. Also, it cannot be performed in case of multiple injuries to the duct.

Diversion of parotid secretion into the mouth can be done by various reconstructive methods which mandate general anaesthesia; including reconstruction of the duct with vein graft, mucosal flaps or suturing of the proximal duct to the buccal mucosa. The other method is the formation of a controlled internal fistula which could be done by double J stent (JJ) urethral catheter [16].

In our case series, both patients did not want a re-surgery under general anaesthesia. The literature reviews on internalisation of sialocele are very few, and a case report by Tandon et al. [17] for post-infection parotid duct sialocele catheterisation with paediatric Ryle’s tube resulted in immediate flow of saliva and patency of duct was effective. However, in our case 1, a Ryle’s feeding tube was used first, but it started to coil inside the cyst and could not be palpated intraorally. So, Foley’s catheter was used in both the cases so that it could be palpated intraorally when inflated. The follow-up time for case 1 was 2 years and case 2 was 3 years. Periodically, the gland was milked and the patient was asked to suck lemon to confirm the salivary flow from the newly formed ductal opening. No extraoral salivary leak was observed thereafter. This is one of the first cases where internalisation is performed using Foley’s catheter.

Our procedure of internalisation of sialocele with cutaneous fistula, using Foley’s catheter, was a very simple outpatient procedure which was performed under local anaesthesia. The catheter can be inflated and deflated whenever necessary. The other main advantage of this procedure is the achievement of immediate results rather than a waiting period as with repeated aspirations, radiotherapy and Botox therapy. This technique is not associated with any complications such as xerostomia which is seen in anti-sialogogue and radiation therapy. It does not need extensive invasive surgery or surgical training on anastomosis. This procedure is also cost-effective. The main limitation of this procedure is that it can be done only in cases where there is sialocele with cutaneous fistula. It cannot be performed where sialocele is absent or immediately after the injury. It can only be done after a few days of injury when the cutaneous fistula is observed. Another limitation is the need for an ultrasonographic machine to confirm the presence of Foley’s catheter inside the sialocele.

Conclusion

Parotid duct injury associated with sialocele and cutaneous salivary fistula could be effectively internalised using Foley’s catheter, under local anaesthesia. This is an indigenous, quick and easy alternative to other complex surgical modalities employed in the management of “parotid duct injury with sialocele”. This is the first case of parotid sialocele managed indigenously by Foley’s catheter.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gehrking E, Remmert S, Meyer S, Krappen S. Microsurgical reanastomosis of the parotid duct. HNO. 1999;47:283–286. doi: 10.1007/s001060050397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naragund AI, Halli VB, Mudhol RS, Sonali SS. Parotid fistula secondary to suppurative parotitis in a 13-year-old girl: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:249. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-4-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Sickels JE. Management of parotid gland and duct injuries. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2009;21(2):243–246. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srinidhi D, Shruthi R. Parotid sialocele and fistulae: current treatment options. Int J Contemp Dent. 2011;2(1):9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marchese-Ragona R, De Filippis C, Marioni G, Staffieri A. Treatment of complications of parotid gland surgery. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2005;25:174–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinberg MJ, Herréra AF. Management of parotid duct injuries. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99(2):136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevenson JH. Parotid duct transaction associated with facial trauma: experience with 10 cases. Br J Plast Surg. 1983;36(1):81–82. doi: 10.1016/0007-1226(83)90019-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis G, Knottenbelt JD. Parotid duct injury: Is immediate surgical repair necessary? Injury. 1991;22:407–409. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(91)90107-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parekh D, Glezerson G, Stewart M, Esser J, Lawson HH. Post-traumatic parotid fistulae and sialoceles. A prospective study of conservative management in 51 cases. Ann Surg. 1989;209(1):105–111. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198901000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Epker BN, Burnette JC. Trauma to the parotid gland and duct: primary treatment and management of complications. J Oral Surg. 1970;28(9):657–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewkowicz AA, Hasson O, Nahlieli O. Traumatic injuries to the parotid gland and duct. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60(6):676–680. doi: 10.1053/joms.2002.33118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sparkman RS. Laceration of parotid duct further experiences. Ann Surg. 1950;131(5):743–754. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195005000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krausen AS, Ogura JH. Sialoceles: medical treatment first. Trans Sect Otolaryngol Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1977;84(5):ORL890-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinberg MJ, Herréra AF. Management of parotid duct injuries. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99:136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canosa A, Cohen MA. Post-traumatic parotid sialocele report of two cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57:742–745. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(99)90445-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aloosi SN, Khoshnaw N. Surgical management of Stenson’s duct injury by using double J stent urethral catheter. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;17:75–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tandon P, Saluja H. Catheterization of post infection parotid duct sialocele with paediatric Ryles tube: a case report. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2018;8:217–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]