Abstract

Background

Carers are key providers of care and support to mental health patients and mental health policies consistently mandate carer involvement. Understanding carers' experiences of and views about assessment for involuntary admission and subsequent detention is crucial to efforts to improve policy and practice.

Aims

We aimed to synthesise qualitative evidence of carers' experiences of the assessment and detention of their family and friends under mental health legislation.

Method

We searched five bibliographic databases, reference lists and citations. Studies were included if they collected data using qualitative methods and the patients were aged 18 or older; reported on carer experiences of assessment or detention under mental health legislation anywhere in the world; and were published in peer-reviewed journals. We used meta-synthesis.

Results

The review included 23 papers. Themes were consistent across time and setting and related to the emotional impact of detention; the availability of support for carers; the extent to which carers felt involved in decision-making; relationships with patients and staff during detention; and the quality of care provided to patients. Carers often described conflicting feelings of relief coupled with distress and anxiety about how the patient might cope and respond. Carers also spoke about the need for timely and accessible information, supportive and trusting relationships with mental health professionals, and of involvement as partners in care.

Conclusions

Research is needed to explore whether and how health service and other interventions can improve the involvement and support of carers prior to, during and after the detention of family members and friends.

Keywords: Systematic review, meta-synthesis, qualitative, carers, involuntary admission

Background

Over the past 70 years, mental health services have transitioned from providing care in psychiatric institutions to providing care in the community. Care in the community often requires the support of family members or friends, referred to as ‘carers’. Greater carer involvement in treatment is associated with significant improvements in symptoms and quality of life, reduced risk of relapse and fewer in-patient admissions.1–4 Accordingly, mental health policies consistently mandate carer involvement in treatment and care.5–8 Although research has highlighted some positive experiences of support,9 many carers report that they feel marginalised or excluded by mental health services10–12 and that their needs and views are often unrecognised and unaddressed,13 which may contribute to carers experiencing stress, burnout and mental health problems.14

Carers report that they find it difficult to be meaningfully involved in their relatives' and friends' care in in-patient as well as community settings, and involuntary in-patient treatment comes with particular challenges.15–18 Despite efforts to reduce the number of patients being treated as psychiatric in-patients, the rates of involuntary admission have been increasing in several European countries.19 Detention under mental health legislation is likely to have a profound impact on both patients and their families and friends. Understanding carers' experiences of and views about assessment for involuntary admission and subsequent detention is crucial to efforts to improve policy and practice and to our knowledge there has been no previous reviews on this subject.

Aims

This review therefore aimed to synthesise qualitative evidence of carers' experiences of the formal assessment of their family and friends for involuntary admission and subsequent detention in a psychiatric hospital. For brevity we frequently refer to ‘detention’ rather than ‘involuntary admission under the Mental Health Act. Any legal processes related to assessment and detention in any country's legislative system were included, for example hearings related to admission or to the appropriateness of continued detention.

Method

Design

We undertook a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis.20

Protocol and registration

Initially we aimed to update two earlier reviews of patient experiences of formal assessment and legal detention21,22 and include the experiences of carers. The search strategy and inclusion criteria were therefore designed for both patients and carers and we registered a single systematic review protocol with PROSPERO (reference CRD42018091721). It became clear during preliminary analysis that the findings for patients and carers were too heterogeneous for a single synthesis. Patient experiences have therefore been reported separately.23 This paper reports the experiences of carers only.

Search strategy

We searched Medline, PsycINFO, HMIC, Embase and Social Sciences Citation Index in January 2018. The search terms are listed in supplementary Appendix 1 (available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.101). Searches were supplemented by reference list screening and forward citation tracking of all included articles and the two earlier reviews.21,22 Citation tracking was conducted using Google Scholar and Web of Science. Searches were limited to papers published after 1983 (the year the Mental Health Act 1983 came into force). This legislative framework for involuntary admission to hospital and treatment in England was updated in 2007 but we chose the earlier date to support identification and retrieval of results over a longer time period. No restrictions were placed on language or country of study.

Inclusion criteria

The original inclusion criteria were applied to identify studies examining either carers' or patients' experiences, but only papers pertaining to the experiences of carers are included in the current review. The original inclusion criteria required that papers (a) reported on patient experiences of being formally assessed for involuntary admission under the Mental Health Act 1983 or equivalent mental health legislation and/or of legal detention in hospital and the experiences of their accompanying carers; (b) reported on patients aged 18 years or above and carers of patients aged 18 years or above; (c) collected data using qualitative methods; and (d) were published in peer-reviewed scientific journals. Studies were excluded if (a) they used a mixed sample of carers of both involuntarily and voluntarily admitted patients with no separate analysis for carers of involuntary patients; (b) reported on assessment for or receiving involuntary treatment in the community only; (c) collected data using individual case studies, auto-ethnography, questionnaires, or surveys; or (d) were systematic reviews, books, commentaries, conference abstracts, dissertations, editorials, government reports or PhD theses. The decision to exclude grey literature was taken because of resource restraints and the difficulties of conducting a systematic and reproducible search of this literature. Multiple papers reporting on the same study could be eligible for inclusion if they presented analyses of different aspects of carer (or patient) experiences of formal assessment for involuntary hospital admission or legal detention.

We defined carers as individuals who provided or intended to provide practical or emotional support to someone with a mental health problem; who may live or not live with the person they cared for; and who may be relatives, partners, friends, or neighbours, in line with the definition used by the UK Department of Health and Social Care.24 Paid carers (i.e. care workers) were not included within this definition. Although the age of patients was limited to 18 years and older, carers of any age were included.

Data screening and extraction

Citations were downloaded to and managed in EndNote. S.F.A. and R.S. screened all titles and abstracts and subsequently S.F.A. independently screened a random 10% of citations. There was 100% agreement. Full texts were screened by R.S. and S.F.A. independently screened all studies selected for inclusion and a random 15% of excluded studies. Again, there was 100% agreement. Bibliographic details and information about study characteristics were extracted into an Microsoft Excel table.

Data synthesis

Data were analysed and synthesised thematically, in a four-stage process. First R.S., S.F.A., P.S. and S.O. independently read the results sections of two carer papers and, line by line, inductively created their own lists of initial codes. Next, R.S., S.F.A., P.S. and S.O. discussed the similarities and differences between their codes and produced a combined list of descriptive themes that they grouped into a hierarchal framework. This thematic framework was shared with the NIHR Mental Health Policy Research Unit's Lived Experience Working Group for feedback. In the third stage, R.S. applied the thematic framework to the remaining manuscripts, and added new themes and collapsed others in an iterative process of coding and analysis. Finally, R.S. and S.O. went beyond the initial synthesis of original study findings and abstracted analytical themes.

Quality appraisal

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative checklist was used to appraise the quality of included studies;25 see supplementary Appendix 2. Quality appraisal was conducted independently by R.S. and Gergana Manolova and they resolved any discrepancies through discussion.

Results

Study characteristics

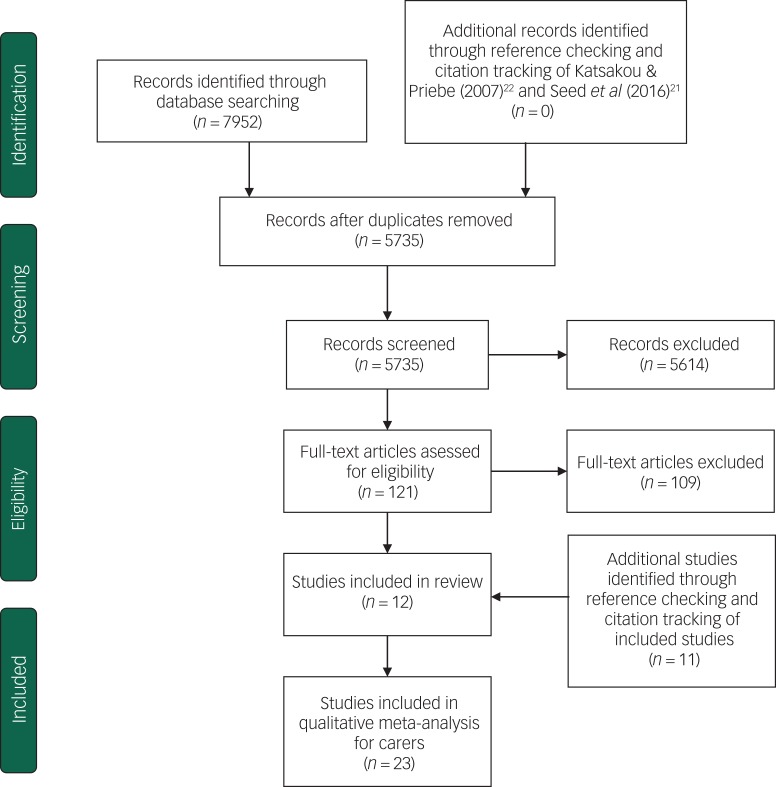

As shown in Fig. 1,26 23 papers were selected:12,16,27–47 16 reported on the experiences of carers only,12,16,34–47 while seven reported on the experiences of patients, carers and other stakeholders.27–33 Study characteristics are summarised in supplementary Table 1 including quality appraisal results that show that 20 of the 23 papers were rated as high-quality studies. Where studies were marked down during quality appraisal, this was often because of studies not having explicitly addressed the relationship between the researcher/s and participants (n = 19). A smaller number of studies were marked down because of a lack of clarity regarding the recruitment strategy or some aspect of the analysis, or because of a lack of information regarding ethical approval. We consider this to have had limited implications for the analysis.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart detailing number of included studies.26

Twelve papers reported on studies conducted in the UK (6 in England,16,29,30,32,34,35 1 in Wales,36 2 in Northern Ireland,28,31 1 in Scotland,12 and 2 not specified37,38), with the remaining studies conducted elsewhere in Europe (Germany,39,40 Greece,41 Norway,42–44 and the Republic of Ireland33), Canada,45 the USA46 and Australia.27,47 Although most studies reported on detention in general psychiatric hospitals, three papers – all conducted in the UK – reported on carers' experiences of assessment and treatment units and forensic services.36–38

At least 260 carers were included in the reviewed studies. It is not possible to be precise because two studies28,30 collected data from groups of an unspecified number, and two studies from Leipzig39,40 analysed subsamples of transcripts from a total of 103 interviews; the subsample sizes were 28 and 42 and the extent of overlap between them is not clear. Study samples ranged in size from 3 participants45 to 103 participants,39,40 with 17 of the 23 selected papers reporting on fewer than 20 carers. Studies generally reported the gender of participants (19 papers included both males and females, two females only,31,45 and 2 did not report participant gender28,32). Across studies reporting the gender of participants, over 70% were female.

Only six studies reported carers' ethnicities: four included all White participants.12,32,34,37 The other two were Gault et al29 who included three African–Caribbean participants and three White participants; and Gerson et al46 who interviewed three African Americans, five White, one East Asian and four Hispanic carers. Another study16 reported patients' ethnicities as White, Asian, Black or mixed but did not provide similar data for carers. Relationships to patients were not reported in three studies.28,29,32 In all but one of the other studies,12 every participant was a relative of the patient they cared for: parents (18 studies), partners (7 studies), and children, siblings or other relatives (10 studies). Only one study reported on the experiences of young carers (i.e. carers under the age of 18).43

Carers' experiences of supporting patients detained under mental health legislation: key themes

Five major themes were identified, relating to (a) the emotional impact of detention on carers; (b) the availability of support for carers of patients assessed for involuntary admission or detained under mental health legislation; (c) the extent to which carers felt involved in decision-making and the provision of care; (d) relationships with patients and staff during detention; and (e) perceptions of care quality. Participant quotes have not been used. Any references to participant names are pseudonyms provided by the authors. Any quotes that refer to a patient as a child are referring to a patient aged 18 years or older.

Emotional impact of detention

Distress was the emotion most frequently described but carers also reported a range of other, often conflicting, emotions in response to the detention of the person for whom they cared.

‘Distress…encompassed mixed feelings including anger, disappointment and frustration.’37

Positive emotions included feelings of relief, hope and gratitude. Reasons for relief included that their concerns about the severity of the person's illness were being acknowledged; that the person was in a safe place; that there was an opportunity for respite and to share responsibility for care with health professionals; and in some cases, that the person they cared for being provided with a diagnosis and information about their illness. Accordingly, some carers felt that detention had been necessary and of benefit to the patient and to them as carers.

‘Participants' accounts of hospitalisation framed it overwhelmingly as an appropriate intervention that brought relief and respite. The young person was understood to be physically contained, with access to appropriate treatment, and hospital was seen as a place of safety, for self and society.’34

Feelings of relief were sometimes accompanied by gratitude, typically when the carer felt acknowledged, supported, and listened to by staff; and had a named contact to provide information. Often, however, feelings of relief were accompanied by a range of negative emotions including distress, guilt, fear, anger, frustration and stress.

For others, feelings of relief were undermined by the realisation that mental health professionals were unable to provide a ‘radical cure’ or clear answers about the aetiology of their relative's illness.41

‘Some …ended up frustrated because of the lack of treatment or experiencing the hospital stay as “only storage.” The gap between expectations and actual experiences could result in retrospective regrets, feelings of blame, and moral distress about initiating the hospitalization process.’44

Feelings of distress were variously attributed by carers to their struggles to find help; their perception that help was not available until the health of their family member or friend had deteriorated to the extent that detention was necessary; the process of detention and their role in it; the treatment provided to their family members and friends; and the lack of opportunity for dialogue with staff. Some carers reported that their distress had a direct impact on their health and well-being.

‘Coping, often with little or no support, with the traumatic and stressful impact of compulsory detention of their relative, had taken significant toll on the carers' physical and mental health. …Common themes among the carers interviewed were depression and suicidal thoughts as they struggled to prevent health crises in households with multiple and complex needs.’12

Some reported that they avoided visiting their relative in hospital to protect themselves from distress. In a small number of cases, distress resulted in carers' complete disengagement from mental health services.

Many carers reported that they felt guilt, feeling responsible for the detention of the person they cared for and believing that they could or should have done more to prevent it. Others felt blamed by health professionals for patients' illnesses.

Fear encompassed fear for the safety of the person they cared for (including the risk that they may be physically harmed by police), of the hospital environment and the risk that the person's health may deteriorate again in future necessitating further admissions. Carers also feared prejudice and stigma being directed against the person they cared for, with examples of carers not speaking to others about their caring responsibilities or the detention of the person they cared for, deepening their sense of isolation.

Anger, frustration and stress were also commonly reported, and related to the difficulty of obtaining help for someone in crisis at the same time as trying to look after them, the lack of accessible information about the assessment and detention process, and not being listened to or consulted.

Availability of support for carers

The lack of adequate support for carers of patients being assessed or detained under mental health legislation was a prominent theme across all papers. Prior to assessment and detention, carers spoke about being overwhelmed by too much responsibility, isolated from sources of support, and expected to manage situations they were ill-equipped to deal with, including risks of self-harm and threats of suicide, until assistance became available.

‘Help to initiate admission was often needed ‘out of hours’, and many reported that it was difficult to access help at these times. Relatives reported not knowing what to do, where to get information and help from, and expressed that this was an extremely stressful and difficult time for them… at this early point, you were “on your own”, struggling to persuade others for assistance.’33

One study suggested that carers could feel fearful about being able to cope and to manage risk when an assessment did not lead to an admission, and the requirements of patient confidentiality left some carers feeling that they did not have enough information to protect themselves.

‘When a mental health assessment did not result in hospital admission, this often led to an increased risk to the family especially when confronted with symptoms resulting in aggression and violence. Family members found a lack of service responsibility particularly when aggression and violence was present.’47

Carers were not always present during detention. One study30 describes the impact on a patient's partner when the decision to detain the patient was taken after she had left the hospital. This carer was at home alone when she received a letter about the detention, news that felt like a ‘clout’. In another study, a daughter caring for her mother, was not informed at all when her mother was detained.44

Visiting hospital was often difficult for carers with multiple caring responsibilities, caring for others who were elderly, disabled or had serious mental or physical health conditions. Many carers also had their own support needs arising from physical and mental health problems, including anxiety and depression. In some cases, carers attributed these problems to the strain of their caring responsibilities:

‘One carer was supporting a spouse with severe mental health problems, a parent with a life-threatening disease, and two adult children both with severe mental health problems, one of whom had recently been detained under the MHCT Act [Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003]. In addition, she suffered debilitating physical health problems that limited her capacity to visit her son when detained in hospital.’12

These carers described needing support and, finding it lacking over successive detentions, a subsequent ‘progressive loss of emotional strength’.39

Although the overwhelming sense of responsibility for care was partially relieved during a period of detention, some also spoke about a loss of purpose during this time, exacerbated by feeling that staff did not recognise them as partners in care or seem to value their insights. Others highlighted that any respite was temporary. Carers' concern about their family member or friend did not diminish during periods of admission to hospital, and fears about the patients' well-being were exacerbated by feeling forgotten about or ignored:

‘Parents' experience of hospitalisation is distressing and bewildering because they are left feeling disregarded and confused about their [18+] child's care. Initial perceptions of feeling contained by hospitalisation appear to subside as parents feel increasingly excluded.’34

Carers reported that they needed support not only in the period prior to assessment and detention but also during this time and afterwards, including to understand what had happened and their role in it.

Carer involvement in decision-making and the provision of care

The extent to which carers felt involved in decision-making and the provision of care was a key influence on carers' experiences of supporting patients detained under mental health legislation. Dimensions of involvement were closely interrelated, but included sharing information, recognising carer expertise and maintaining dialogue. Carers' legal status in relation to the patient (either as their relative or a person nominated to represent their interests) afforded them different rights to information and involvement and thus affected their experience of supporting patients who were subject to detention.

Carers spoke frequently about needing accessible information prior to, during and after detention. This included information about patients' illnesses, medication and needs; plans for assessment, admission, care and for discharge; hospital and community care processes; and the legal rights and entitlements of both patients and them as carers. Yet, information was often lacking. This was particularly challenging for carers of people who had not previously been in contact with mental health services, who reported that it could be very difficult to find out where and how to seek help while looking after a person who was acutely unwell. Martinsen et al found that no one talked to young next of kin about detention even when they had been the one who telephoned for assistance or had witnessed their family member being detained.43

After detention it was a source of frustration to many carers to not be involved in discharge planning, reporting that they found themselves having to take responsibility for patients who were discharged from hospital but whom they did not consider to be well.

Carers identified a major barrier to accessing information as the claims made by staff regarding patient confidentiality.

‘Family caregivers…understood that confidentiality was a delicate issue, but sometimes considered that if they were providing care for the patient they needed to know relevant information. This information was important in protecting family caregivers from risks but also in allowing them to optimise the level of care.’16

Carers also described frustrations arising from wanting to be able to provide staff with information confidentially, rather than the information being shared with the patient. Indeed, carers felt that they had useful knowledge and experience to share with staff but reported that they had not had opportunities to do so or were not listened to or taken seriously by staff.

‘Parents wanted to be treated as a resource and described recognizing patterns of emotions and behaviours. They hoped that by sharing these with health professionals, they would make better and more informed treatment decisions.’37

In addition to discussing the need for timely and accessible information, carers spoke about their expectations around the quality and tone of communication and the need for dialogue rather than a one-way flow of information. These expectations were often not met. The information that was provided before, during and after detention was often given during times of chaos and stress, making it hard to process and recall.

‘Some relatives described being so traumatized by the experience that, when asked if they had been the signatory to the application [for involuntary admission in the Republic of Ireland], they were not sure if they were or not.’33

Carer relationships with patients and staff during detention

The detention of a patient could lead to the breakdown of the relationship between the patient and carer. Some spoke about how their friend or family member had refused contact with them during the time they were detained, and about the distress this had caused them. Many carers described how the person they cared for blamed them for their detention and felt betrayed that they had called the emergency services or agreed to their admission to hospital.

‘Throughout participants' accounts, there was the perception that the young person blamed the parent as the cause of their distress [at being detained], and this was difficult for parents to reconcile with their belief that they were “doing the best” for them.’34

Where carers were able to visit patients there was, nonetheless, often a reduction in contact with them and, for some carers, efforts to maintain involvement and relationships were hampered by their geographical distance from the hospital.

‘[Carers] describe how they and their sick family member “lose each other” due to long hospitalisations. This breaking of family bonds is particularly problematic if the family is responsible for practical and emotional support following hospitalisation.’42

Carers spoke about the impact of detention on the family.16 Other carers, particularly young carers, felt the loss of being with the patient as they had been before, a sibling or parent they missed and loved.43 One study also described how a carer's role in seeking detention and the power imbalance that revealed could cast a ‘shadow’ over couples, requiring the renegotiation of relationships and the regaining of trust.30

Across several papers many, though not all, carers described their relationships with healthcare professionals, and their experiences of mental health services, prior to and during detention as having been unsatisfactory.

‘“It's a terrible battle” … describes the relationships between parent caregivers and mental health professionals before and after admission …. The majority of parents described a strained and invalidating relationship with professionals.’37

During the time their relatives were detained, many carers described being disregarded or treated as strangers by staff, who they felt, as well as not engaging with them in an effective partnership, did not acknowledge the impact that detention might be having on their family. Positive relationships with members of staff were infrequently reported but had a powerful impact on how carers experienced detention:

‘Whether the healthcare professionals smile, show respect, and demonstrate that they acknowledge the family member is an important indicator of whether coercion is perceived as a violation or help, as a failure or success.’44

Quality of care

Quality of care was the final theme and seemed ultimately to define carers' feelings about the detention of their family members. It was discussed predominantly in relation to the timeliness, appropriateness and responsiveness of care provided to family members in the period leading up to detention. Carers were desperate to get earlier, preventative help rather than having to wait until patients were in crisis and posed a risk of harm to themselves or others. By the time assessment and detention occurred many carers already felt let down by health services. While acknowledging the necessity of detention at that point, they had profound misgivings.

‘… the fact that Linda's mother was offered help too late was a heavy load on the family because they ended up with coercive interventions that they had to take responsibility for. What followed coercive hospitalization was perceived as deeply problematic…’44

However, carers also spoke about the quality of care received during the period of hospital admission, with some regretting the detention after being disappointed by an apparent lack of treatment and meaningful recovery.

‘…several participants reported that their distress regarding coercion stemmed from what they considered low-quality care, such as a lack of adequate treatment and custodial care and the use of coercion based on staff convenience or bad attitudes, shortage of staff or available services.’44

Carers described various delays to assessment and treatment prior to detention (especially out of hours), and difficulties navigating services and finding a member of staff with whom to speak. This, they suggested contributed to the deterioration both of patients' conditions and of relationships with patients and staff. Many carers reported that services were not proactive or sufficiently responsive either to the needs of the patients or of carers. Services were described by many carers as not recognising the severity of patients' illnesses, which was particularly problematic when patients also did not acknowledge how unwell they had become, and as not intervening until patients had deteriorated to such an extent that detention became inevitable.

‘Family members were unable to obtain early intervention […]; they had difficulty obtaining assistance until the [patient] consumer was acutely unwell or at crisis point. The family felt ignored by the [mental health service] despite their persistence.’47

Detention processes were described by many carers as inappropriate or heavy-handed. Examples included the use in Australia of caged police vehicles to transport patients,27 the use of police stations and accident & emergency departments32 as places of safety in the UK, and armed police attending to detain a young woman at risk of self-harm in the USA.46 Conversely, Bradbury et al also reported a response that was proactive, gentle and de-escalating.

‘One carer described [that] a police officer had spent time talking with her child, managing to de-escalate the situation to the point where the child had no longer needed to be transported for assessment. The police officer then returned the following day to check that the child had remained stable. The carer described this with deep gratitude and relief.’27

A small number of studies described carers' shock upon visiting their relatives in hospital. This related predominantly to the security measures in place – such as close observation of their interactions with patients and having their bags checked on entry to the ward – as well as to observing their relatives having been heavily medicated.

‘When he visited Rob in hospital, he was shocked by his son's vacant, heavily medicated condition (there was “just nothing there”) and by the environment in which he found him …For Jim, this early experience of engaging with his son's connection to mental health services was powerful, emotive and very negative in its impact.’35

Carers also reported dissatisfaction with the duration of admissions, reporting having had to care for patients discharged at short notice or while still very unwell. In two studies, conducted in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, carers questioned whether mental health tribunals were working in the best interests of their family members. In one study, carers described cases in which tribunals had revoked orders before they believed their family members was ready for discharge33 and in the second, the author reported cases having been ‘regraded’ to voluntary status shortly before Tribunal hearings.28

Discussion

Main findings

Despite the potential for different legal systems resulting in different experiences for carers, the themes of this review were strikingly consistent across the included studies and across time and setting. Themes also resonated with the wider literature on carers' experiences of supporting patients and engaging with mental health services.48–50 In describing their experiences of the detention of their family members under mental health legislation, and the period leading up to this, carers spoke about the need for timely and accessible information, of supportive and trusting relationships with mental health professionals, and of involvement as partners in care.

Carers' information needs included information about their family members' illnesses, why they were being detained for treatment, procedures for discharge, the legal rights of both the patient and of them as carers, and the boundaries and implications of patient confidentiality. Carers stressed the importance of dialogue with staff but reported that verbal information was difficult to process in stressful or chaotic situations. Written information was therefore also important. During a process that could be frightening, carers' experience could be transformed by staff who treated them with kindness and respect, valued them as a resource, and actively acknowledged and addressed their needs. Similar findings have been discussed in previous guidelines and reports.7,14,51,52

Across several papers, carers spoke about the impact of detention on their own emotional well-being. Detention was described by many as traumatic, a process of extreme stress and internal conflict when, out of desperate concern for the safety of the patient (and in some cases that of themselves and/or others) and a desire to see the relief of patients' suffering, they consented to an intervention they had been struggling to avoid.53 In some cases detention was described by carers as humiliating both for the patient and themselves. This compounded the impact of having witnessed deterioration in the mental health of the person they cared for in the lead up to detention and the strain of providing support during this time. When speaking about the emotional impact of detention, carers also described anger, frustration, grief, guilt and fear. Anger and frustration were associated with the often-protracted difficulties of obtaining help for the patient, and, during detention, feeling disregarded or excluded by staff. Grief, guilt and sadness arose from feelings of failure to prevent detention, of separation and, in some cases, new information of or about a diagnosis and its long-term implications.

Carers felt conflicted about detention of their relatives. Although they ultimately felt it was the right decision, given the deterioration in their relatives' mental health, they were anxious about how patients would be treated while detained and about how they would cope in a hospital environment. They were also fearful of the consequences for their relationship with their relative, worrying that the patient would react negatively to their having had a role in initiating the detention and about a consequent loss of trust. In places with arrangements for alternative signatories to applications for admission for assessment such as approved social workers in Northern Ireland,31 carers were keen that these individuals should be meaningfully available so that carers were not required to take on this responsibility by default.

While their family members were in hospital, carers' feelings of powerlessness and isolation were exacerbated by limited opportunities for involvement in care. The loss of ordinary interaction and time simply ‘being together’ with a loved patient was felt keenly by young next of kin.43 Carers, who, out of a sense of loyalty to the patient, had avoided talking to family and friends about their mental illness, were particularly vulnerable and isolated, describing feelings of ‘deep loneliness and insufficient social support’.42

The observed consistency of themes across time is disappointing, suggesting a lack of progress in improving carers' experiences of supporting patients prior to, during and after assessment and detention under mental health legislation. For example, Crisanti writing in Canada in 2000,45 and Finlay-Carruthers and colleagues, writing in Scotland in 2018,37 both highlight carers' struggles to have their child admitted to hospital and their exasperation at their knowledge and experience being ignored. We note that a number of the issues raised by the studies included in this review have also been highlighted by guidelines aimed at improving carer experiences, such as the carer-co-authored ‘Triangle of Care: A Guide to Best Practice in Acute Mental Health’ which was first published in England almost a decade ago.14

Strengths and limitations of the review

This review employed a robust search strategy and independent screening of random samples of downloaded records demonstrated a high level of agreement. Analysis and interpretation of data was informed by discussion with the NIHR Mental Health Policy Research Unit's Lived Experience Working Group. S.F.A., K.M. and K.P. are experienced carers. However, some limitations should be noted. Carers of child and adolescent patients were not included in the scope of this review. Also excluded were carers' experiences of community treatment orders (CTOs, a form of compulsory community treatment) and the perspectives of mental health and other professionals involved in the assessment of patients for involuntary admission and detention under mental health legislation.

Few studies explored the experiences of carers of patients detained in forensic settings, precluding analysis of whether and how they differed to those of carers of patients detained in acute care settings. The process of synthesising findings across multiple qualitative studies, conducted in different settings, with different legislative systems, and using different methods, involved simplification and loss of nuance. During analysis we were not able to analyse data separately by patient or carer characteristics (such as experiences of Black, Asian, and minority ethnic participants) because of small samples and lack of focus on these questions. For example, although more than 70% of participants in studies that reported the gender of carers were female, studies did not analyse whether experiences differed between men and women. Similarly, studies did not analyse potential differences accordingly to patient diagnosis. We were not able to analyse similarities and differences by country or period, because of the limited time and resources available. Although a high degree of consistency was found across studies with regards to the themes generated, generalisability beyond the included studies cannot be assumed.

Future research

Although themes were consistent across studies, we found little analysis of whether carers' experiences varied with regards to, for example, the gender of either the patient or the carer, the patient's diagnosis, their age or their ethnicity. Future research should seek to explore whether these factors influence carers' experiences of detention and should investigate the experiences of young carers and Black, Asian and minority ethnic carers, who were underrepresented within research on this topic. Research should also seek to explore how different legislative arrangements have an impact on carer experiences of involuntary admission.

In our selected studies there was little specifically about assessments under mental health legislation but the review does demonstrate that detention under mental health legislation has an impact on the well-being of not only patients but also their carers and wider families. There is a clear need for mental health services to work in partnership with carers, whether patients are in the community, in crisis at home, or on in-patient wards and to work to mitigate the negative consequences of detention for carers' well-being and relationships. We do not underestimate the skill, commitment, resources and time needed by health professionals to do this work well.54 Future research should develop and test strategies, co-produced by patients, carers and clinicians, to inform, involve and support carers prior to, during and after the detention of their relatives and friends.

Box 1.

A lived experience commentary

This study was limited to considering the results from a very specific range of qualitative studies of carers' experiences around detention. The research team identified several gaps and offer the realistic conclusion that there is a need for further research to explore how to support carers.

However, carers rarely talk about their own needs. They might talk about their own feelings of distress at their relative's experiences, but they will swiftly move on to talk about the support their relative needs; or they will talk about their need for information, advice and guidance on how best to support their relative or friend. Discussions of support for carers consequently focus on supporting carers to support someone else, not support for themselves. Future researchers need to appreciate the challenge of enabling carers to talk about their own needs.

Additionally, we highlight the range of carers' experiences. There is a risk throughout in referring to ‘carers’ as if this is one homogenous group. The caring role crosses all demographic characteristics and uses of different services. People from Black African–Caribbean communities have a disproportionately high rate of detention, as well as longer duration of untreated illness, with an impact on social networks. Young carers may not be identified where other family members are considered to be the primary carer. There are also experiences that are not talked about, such as supporting someone with a history of self-harm and suicide attempts, or the impact on the wider family of police involvement.

However, while agreeing with the need for further research, we are also mindful that carers have been repeatedly consulted for decades, as reported in the grey literature and other papers that were not included in this review. We would argue that it is also time for services to act, taking on initiatives such as ‘Triangle of Care’, so that carers become equal ‘Partners in Care’.

Karen Machin and Karen Persaud

Acknowledgements

We thank all the authors and participants of the selected studies on whose work and experiences we have drawn. We gratefully acknowledge feedback and support provided by members of the NIHR Mental Health Policy Research Unit's Lived Experience Working Group in providing expert commentary, analysing and interpreting data and advising on terminology. We are also grateful to P.S. for contributing to the development of the thematic framework and implications for practice; and to Gergana Manolova for assisting with the quality appraisal as an independent reviewer.

Funding

This paper is based on independent research commissioned and funded by the National Institute for Health Research Policy Research Programme. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, the Department of Health and Social Care or its arm's length bodies, or other Government Departments.

Author contributions

R.S. searched and selected studies; conducted reference and citation tracking, quality appraisal and data extraction; developed the thematic framework; analysed data; and drafted the first version of the manuscript. S.F.A. developed the review protocol and search terms, searched databases, screened selection as second reviewer, reference and citation tracking, data extraction and thematic framework. K.M. critically revised the thematic framework, implications for practice and the draft manuscript. K.P. critically revised the thematic framework and the draft manuscript and contributed to the development of implications for practice. A.S. advised on the scope of review and implications for practice. S.J. conceptualised the review and advised on scope and implications for practice. S.O. supervised the review; oversaw the development of thematic framework and analysis; contributed to implications for practice; and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.101.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- 1.Fleury MJ, Grenier G, Caron J, Lesage A. Patients’ report of help provided by relatives and services to meet their needs. Community Ment Health J 2008; 44: 271–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tempier R, Balbuena L, Lepnurm M, Craig TK. Perceived emotional support in remission: results from an 18-month follow-up of patients with early episode psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2013; 48: 1897–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scofield N, Quinn J, Haddock G, Barrowclough C. Schizophrenia and substance misuse problems: a comparison between patients with and without significant carer contact. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2001; 36: 523–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norman RM, Malla AK, Manchanda R, Harricharan R, Takhar J, Northcott S. Social support and three-year symptom and admission outcomes for first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res 2005; 80: 227–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Australian Government. Carer Recognition Act 2010 Australian Government, 2010.

- 6.Liu J, Ma H, He Y-L, Xie B, Xu Y-F, Tang H-Y, et al. Mental health system in China: history, recent service reform and future challenges. World Psychiatry 2011; 2011: 210–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Psychosis and Schizophrenia in Adults. National Clinical Guideline 178 NICE, 2014.

- 8.Department of Health. Recognised, Valued and Supported: Next Steps for the Carers Strategy. Cross-Government publication, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scottish Executive. The Future of Upaid Care in Scotland - Appendices 1–5 Scottish Executive, 2006.

- 10.Cree L, Brooks HL, Berzins K, Fraser C, Lovell K, Bee P. Carers’ experiences of involvement in care planning: a qualitative exploration of the facilitators and barriers to engagement with mental health services. BMC Psychiatry 2015; 15: 208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Commission on Acute Adult Psychiatric Care. Old Problems New Solutions: Improving Acute Psychiatric Care for Adults in England. Commission on Acute Adult Psychiatric Care, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ridley J, Hunter S, Rosengard A. Partners in care?: Views and experiences of carers from a cohort study of the early implementation of the Mental Health (Care & Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003. Health Soc Care Community 2010; 18: 474–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee M. Improving Services and Support for Older People with Mental Health Problems: The second report from the UK Inquiry into Mental Health and Well-Being in Later Life Age Concern, 2007. (http://www.mentalhealthpromotion.net/resources/improving-services-and-support-for-older-people-with-mental-health-problems.pdf).

- 14.Carers Trust. The Triangle of Care. Carers Included: A Guide to Best Practice in Mental Health Care in England. Carers Trust, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clissett P, Porock D, Harwood RH, Gladman JR. Experiences of family carers of older people with mental health problems in the acute general hospital: a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs 2013; 69: 2707–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jankovic J, Yeeles K, Katsakou C, Amos T, Morriss R, Rose D, et al. Family caregivers’ experiences of involuntary psychiatric hospital admissions of their relatives--a qualitative study. PLoS One 2011; 6: e25425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nurjannah I, Mills J, Usher K, Park T. Discharge planning in mental health care: an integrative review of the literature. J Clin Nurs 2014; 23: 1175–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkinson C, McAndrew S. ‘I'm not an outsider, I'm his mother!’ A phenomenological enquiry into carer experiences of exclusion from acute psychiatric settings. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2008; 17: 392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fakhoury W, Priebe S. Deinstitutionalization and reinstitutionalization: major changes in the provision of mental healthcare. Psychiatry 2007; 6: 313–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lachal J, Revah-Levy A, Orri M, Moro MR. Metasynthesis: an original method to synthesize qualitative literature in psychiatry. Front Psychiatry 2017; 8: 269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seed T, Fox JR, Berry K. The experience of involuntary detention in acute psychiatric care. A review and synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Nurs Stud 2016; 61: 82–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katsakou C, Priebe S. Patient's experiences of involuntary hospital admission and treatment: a review of qualitative studies. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc 2011; 16: 172–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akther SF, Molyneaux E, Stuart R, Johnson S, Simpson A, Oram S. Patients’ experiences of assessment and detention under mental health legislation: systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. BJPsych Open 2019. May; 5: e37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Department of Health. Refocusing the Care Programme Approach Department of Health, 2008.

- 25.CASP. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Qualitative Checklist. CASP, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. The PRISMA statement: preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bradbury J, Hutchinson M, Hurley J, Stasa H. Lived experience of involuntary transport under mental health legislation. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2017; 26: 580–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell J. Stakeholders’ views of legal and advice services for people admitted to psychiatric hospital. J Soc Welfare Family Law 2008; 30: 219–32. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gault I, Gallagher A, Chambers M. Perspectives on medicine adherence in service users and carers with experience of legally sanctioned detention and medication: a qualitative study. Patient Prefer Adherence 2013; 7: 787–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henderson J. Experiences of ‘care’ in mental health. J Adult Prot 2002; 4: 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manktelow R, Hughes P, Britton F, Campbell J, Hamilton B, Wilson G. The experience and practice of approved social workers in Northern Ireland. Br J Soc Work 2002; 32: 443–61. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riley G, Freeman E, Laidlaw J, Pugh D. ‘A frightening experience’: detainees’ and carers’ experiences of being detained under Section 136 of the Mental Health Act. Med Sci Law 2011; 51: 164–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smyth S, Casey D, Cooney A, Higgins A, McGuinness D, Bainbridge E, et al. Qualitative exploration of stakeholders’ perspectives of involuntary admission under the Mental Health Act 2001 in Ireland. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2017; 26: 554–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hickman G, Newton E, Fenton K, Thompson J, Boden ZV, Larkin M. The experiential impact of hospitalisation: parents’ accounts of caring for young people with early psychosis. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2016; 21: 145–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wane J, Larkin M, Earl-Gray M, Smith H. Understanding the impact of an assertive outreach team on couples caring for adult children with psychosis. J Fam Ther 2009; 31: 284–309. [Google Scholar]

- 36.James N. Family carers’ experience of the need for admission of their relative with an intellectual disability to an assessment and treatment unit. J Intellect Disabil 2016; 20: 34–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Finlay-Carruthers G, Davies J, Ferguson J, Browne K. Taking parents seriously: the experiences of parents with a son or daughter in adult medium secure forensic mental health care. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2018; 27: 1535–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williamson H, Meddings S. Exploring family members’ experiences of the Assessment and Treatment Unit supporting their relative. Br J Learn Disabil 2018; 46: 233–240. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jungbauer J, Angermeyer MC. Living with a schizophrenic patient: a comparative study of burden as it affects parents and spouses. Psychiatry 2002; 65: 110–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jungbauer J, Wittmund B, Dietrich S, Angermeyer MC. The disregarded caregivers: subjective burden in spouses of schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Bull 2004; 30: 665–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Darmi E, Bellali T, Papazoglou I, Karamitri I, Papadatou D. Caring for an intimate stranger: parenting a child with psychosis. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2017; 24: 194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Forde R, Norvoll R, Hem MH, Pedersen R. Next of kin's experiences of involvement during involuntary hospitalisation and coercion. BMC Med Ethics 2016; 17: 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martinsen EH, Weimand BM, Pedersen R, Norvoll R. The silent world of young next of kin in mental healthcare. Nurs Ethics 2019; 26: 212–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Norvoll R, Hem MH, Lindemann H. Family members’ existential and moral dilemmas with coercion in mental healthcare. Qual Health Res 2018; 28: 900–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crisanti AS. Experiences with involuntary hospitalization: a qualitative study of mothers of adult children with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2000; 45: 79–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gerson R, Davidson L, Booty A, Wong C, McGlashan T, Malespina D, et al. Families’ experience with seeking treatment for recent-onset psychosis. Psychiatr Serv 2009; 60: 812–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hallam L. How involuntary commitment impacts on the burden of care of the family. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2007; 16: 247–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuipers E, Onwumere J, Bebbington P. Cognitive model of caregiving in psychosis. Br J Psychiatry 2010; 196: 259–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rowe J. Great expectations: a systematic review of the literature on the role of family carers in severe mental illness, and their relationships and engagement with professionals. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2012; 19: 70–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lavis A, Lester H, Everard L, Freemantle N, Amos T, Fowler D, et al. Layers of listening: qualitative analysis of the impact of early intervention services for first-episode psychosis on carers’ experiences. Br J Psychiatry 2015; 207: 135–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Service-User Experience in Adult Mental Health: Improving the Experience of Care for People using Adult NHS Mental Health Services NICE, 2011. [PubMed]

- 52.Department of Health. Reference Guide to the Mental Health Act 1983. The Stationery Office, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Albert R, Simpson A. Double deprivation: a phenomenological study into the experience of being a carer during a mental health crisis. J Adv Nurs 2015; 71: 2753–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eassom E, Giacco D, Dirik A, Priebe S. Implementing family involvement in the treatment of patients with psychosis: a systematic review of facilitating and hindering factors. BMJ Open 2014; 4: e006108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.101.

click here to view supplementary material