Abstract

Despite immense concern over amplified warming in the Arctic, physiological research to address related conservation issues for valuable cold-adapted fish, such as the Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus), is lacking. This crucial knowledge gap is largely attributable to the practical and logistical challenges of conducting sensitive physiological investigations in remote field settings. Here, we used an innovative, mobile aquatic-research laboratory to assess the effects of temperature on aerobic metabolism and maximum heart rate (fHmax) of upriver migrating Arctic char in the Kitikmeot region of Nunavut in the central Canadian Arctic. Absolute aerobic scope was unchanged at temperatures from 4 to 16°C, while fHmax increased with temperature (Q10 = 2.1), as expected. However, fHmax fell precipitously below 4°C and it began to plateau above ~ 16°C, reaching a maximum at ~ 19°C before declining and becoming arrhythmic at ~ 21°C. Furthermore, recovery from exhaustive exercise appeared to be critically impaired above 16°C. The broad thermal range (~4–16°C) for increasing fHmax and maintaining absolute aerobic scope matches river temperatures commonly encountered by migrating Arctic char in this region. Nevertheless, river temperatures can exceed 20°C during warm events and our results confirm that such temperatures would limit exercise performance and thus impair migration in this species. Thus, unless Arctic char can rapidly acclimatize or alter its migration timing or location, which are both open questions, these impairments would likely impact population persistence and reduce lifetime fitness. As such, future conservation efforts should work towards quantifying and accounting for the impacts of warming, variable river temperatures on migration and reproductive success.

Keywords: Arctic char, Arctic fisheries, cardiorespiratory, climate change, fish physiology, thermal tolerance

Introduction

The Canadian Arctic has warmed at close to three times the average global rate, raising concern among northerners, scientists, and policymakers alike (Galappaththi et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). Despite this concern, we know little about the environmental physiology of many Arctic species, even though such knowledge is fundamental to a mechanistic understanding of the ecological impacts of climate change (Cooke and O’Connor, 2010; Cooke et al., 2012; Cooke et al., 2013; Patterson et al., 2016). Indeed, knowledge regarding thermal limitations to metabolism, growth, and exercise performance is increasingly being used to develop evidence-based management strategies for many fishes (Cooke et al., 2012; DFO, 2012; Patterson et al., 2016). For instance, the allowable harvest of Pacific and Atlantic salmon is now adjusted based on river temperatures, in part, using knowledge that high temperatures, by impairing salmon cardiac performance, capacity for aerobic exercise, and recoverability, can reduce survival during migration (Farrell et al., 2008; Eliason et al., 2011; DFO, 2012; Patterson et al., 2016). Equivalent knowledge for use in management decisions remains sparse for Arctic fishes, largely due to the exorbitant cost of northern research (Mallory et al., 2018), technical limitations of conducting sensitive physiological research in remote field settings (Farrell et al., 2003; Mochnacz et al., 2017; Gilbert and Tierney, 2018), and the absence of field-based infrastructure available to support such research.

This limited physiological knowledge base is particularly concerning for keystone species such as the Arctic cod (Boreogadus saida; Drost et al., 2016) and for our focal species, the Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus), which has immense cultural, subsistence and economic value to northern communities (Roux et al., 2011; Day and Harris, 2013; Roux et al., 2019). What little is known regarding wild Arctic char thermal physiology indicates that, like other anadromous salmonids, their thermal physiology likely varies with life stage, thermal history and population of origin. For instance, juvenile Arctic char in the central Canadian Arctic can maintain their exercise capacity over temperatures from 10 to 21°C but nevertheless struggle to recover from exhaustive exercise above 20°C (Gilbert and Tierney, 2018). In contrast, the maximum heart rate (fHmax) of larger sea-run Arctic char in Greenland (presumably acclimated to sea surface temperatures of ~ 7°C) became thermally limited at just 13°C and the heart failed altogether by 15°C (Hansen et al., 2016); the optimal temperature for cardiorespiratory performance was estimated as ~ 7°C, based on the rate of increase in fHmax decreasing above 7°C. This temperature is well below the maximums seen in Canadian Arctic rivers through which Arctic char migrate in summer (Gilbert et al. 2016).

Anadromous Arctic char certainly experience dramatic shifts in available and experienced temperatures throughout their life history and broad, circumpolar distribution (Gilbert et al. 2016; Mulder et al., 2019; Harris et al. 2020). Juveniles typically rear in cool freshwater lakes (typically < 4°C; Godiksen et al., 2012) until they are large enough (~3–6 years old, > 180 mm; Johnson, 1989; Gilbert et al., 2016) to undertake a spring migration to their marine feeding environment where they spend most of their time at milder temperatures (~4–11°C; Rikardsen et al., 2007; Spares et al., 2012; Mulder et al., 2019; Harris et al., 2020), with occasional brief dives to frigid waters (−2 to 0°C). Unlike most anadromous salmonids, to avoid freezing over winter in seawater Arctic char must return to freshwater in late summer or fall and typically repeat this migration cycle many times throughout their life (Johnson, 1989; Gyselman, 1994; Klemetsen et al., 2003; Moore et al., 2016). Their up-river return migrations are among the greatest physical and thermal challenges in their lives (Gilbert et al., 2016). They can encounter conditions ranging from high-flow rapids to water so shallow that they are only partially submerged, and temperatures that can vary dramatically from ~ 0 to 21°C (present study; Gilbert et al., 2016; Gilbert and Tierney, 2018).

This variable thermal history, the rapid warming of the Arctic and inter-study differences in thermal tolerance provide the impetus for field-based research on the thermal physiology of Arctic char. To this end, we used innovative mobile Arctic research infrastructure and simplified physiological techniques to allow for a field-based assessment of the thermal limits to cardiorespiratory performance for migrating Arctic char in the central Canadian Arctic. Based on their range of encountered migration temperatures, we predicted that Arctic char in this region should have a relatively broad cardiorespiratory thermal performance and would tolerate temperatures warmer than those found in the only other comparable study of wild Arctic char (Hansen et al., 2016). The overall goal of the study is to provide insight into how current and future thermal regimes may impact Arctic char cardiorespiratory physiology and thus migration success in the face of rapid warming.

Methods

Study animals and mobile research laboratory

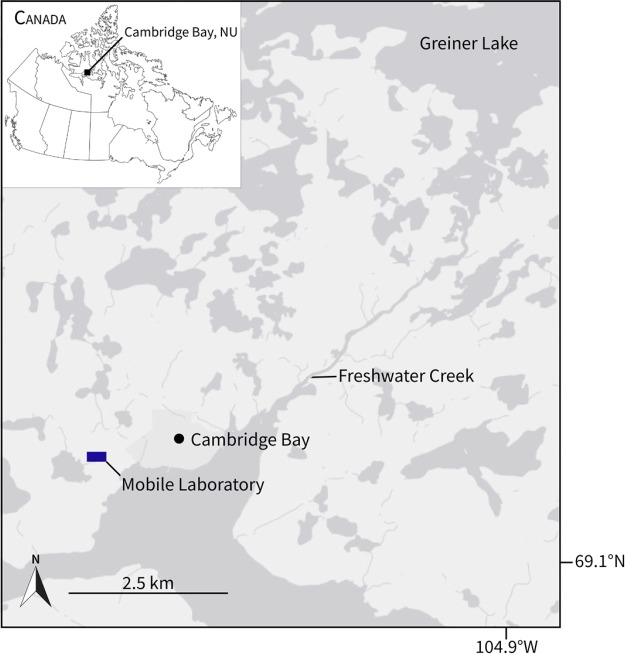

All sampling and animal use was approved by Fisheries and Oceans Canada Freshwater Institute (AUP 2016-033, AUP 2017-039, LFSP S-16/17 1028-NU, LFSP S-17/18 1023-NU). In the summers of 2016 and 2017, anadromous Arctic char (2016: n = 20 length = 385 ± 13 mm (mean ± SEM), mass = 605 ± 61 g; 2017: n = 12 length = 407 ± 27 mm, mass = 711 ± 209 mm) were caught by angling with barbless hooks at the mouth or in the lower reach (850 m) of Freshwater Creek, NU, Canada (69°07′N, 104°59′W; Fig. 1), where there is an important subsistence fishery for Inuit from the community of Cambridge Bay. Captured fish were transported in an aerated 90-L cooler by all-terrain vehicle (ATV) to a nearby (<7 km) mobile research laboratory (Arctic Research Foundation, Winnipeg, CAN; Fig. S1) equipped with a 450-L temperature-controlled fish holding system (Aqua Logic Inc., San Diego, USA), where they were held at commonly encountered river temperatures (~10–12°C). The mobile laboratory was constructed out of a standard 6.1 × 2.4 × 2.4 m (20 × 8 × 8 feet) shipping container and equipped with 15 × 305 W solar panels, 2 × 1.1 kW wind turbines, a backup 10 kW diesel generator, 24 × 2 V batteries and 2 × 6.8 kW inverter and charging systems (Fig. S1). The laboratory was also fitted with bench space (~2 m2), equipment storage and a composting toilet.

Figure 1.

Study area around the hamlet of Cambridge Bay in the Kitikmeot region of Nunavut, Canada. Anadromous Arctic char were captured at the mouth or in the lower 850 m of Freshwater Creek, which drains the Greiner watershed into the Arctic Ocean.

Respirometry and critical thermal maxima

In 2017, respirometry was conducted at temperatures from 3.7 to 20.0°C (n = 12). Arctic char were allowed to recover overnight (>12 h) following capture prior to these experiments. To begin, fish were warmed at 2°C h−1 to the test temperature and held at that temperature for 1 h. They were then chased to fatigue (time to fatigue: 4.4 ± 0.2 min), given 1.3 ± 0.1 min air exposure, during which a ~ 200 μL caudal blood sample was drawn, and the fish was rapidly sealed in a 30-L respirometer (90 cm long × 20.3 cm diameter). Fatigue was defined as the fish being refractory to a tail and mid-body grab for > 5 s. Fish were then allowed to recover for a minimum of 18 h in the respirometer after which they were warmed at rate of 5°C h−1 until they reached their critical thermal maximum (CTMax), the temperature at which they could no longer maintain dorsoventral equilibrium. This protocol allowed us to reliably estimate maximum (ṀO2Max) and minimum (ṀO2Min) oxygen consumption rates, calculate absolute and factorial aerobic scope (AAS: ṀO2Max − ṀO2Min; FAS: ṀO2Max/ṀO2Min), record MO2 during acute warming and estimate CTMax. AAS serves as a measure of the net aerobic capacity available above rest while FAS is a measure of the capacity to increase ṀO2 above ṀO2Min in a multiplicative manner. Whether an aerobic function is constrained by AAS or FAS as temperature increases will depend on how its aerobic cost scales with temperature relative to the available scope (see Farrell, 2016; Hasley et al., 2018). Hematocrit (Hct), haemoglobin (Hb) content (HB 201, HemoCue, Ängelholm, SWE), blood glucose (Accu-Chek Aviva, Roche, Basel, CHE) and blood lactate concentration (Lactate Pro, Arkray KDK, JPN) were measured in duplicate immediately following the chase and at CTMax. Hb values were adjusted as previously described for fish (Clark et al., 2008) and mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration (MCHC) was also calculated (Hb/Hct). Once the fish was sealed in the respirometer, intermittent flow respirometry was performed as previously described (Svendsen et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2018) and the measurement and flush period varied based on the temperature, size of the fish and time post-chase to ensure an adequate ṀO2 signal was obtained (R2 > 0.8) and dissolved oxygen remained above 80% air saturation (Chabot et al., 2016). A full water change was conducted between each experiment to limit microbial load and waste accumulation. ṀO2Max was estimated using an iterative algorithm to identify the steepest slope in dissolved oxygen over any measurement period (Zhang et al., 2018). ṀO2Min was taken as the lowest 25% of the data recorded after 12 h of recovery (Chabot et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2018). ṀO2 was recorded once every 12 min during warming from the test temperature at ~ 1°C increments as previously described (Gilbert et al., 2019).

Heart rate assessment

Cardiac thermal tolerance was assessed in 2016 on anaesthetized fish fitted with electrocardiogram (ECG) electrodes in a manner similar to previous studies on other salmonids (Casselman et al., 2012; Anttila et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2015) and notably, in Greenlandic Arctic char (Hansen et al., 2016) and Arctic cod (Drost et al., 2016). To begin each experiment, two fish were anesthetized in 150 mg L−1 buffered tricaine methanesulfonate (TMS; 1:1.5 sodium bicarbonate) at 10°C until ventilation slowed, almost to a stop and was only intermittent. Fish were then weighed and transferred to a well-aerated anaesthetic bath containing 65 mg L−1 buffered TMS where they were placed supine, their gills were irrigated with a pump. Stainless steel electrodes were inserted into the skin over the heart on the right side of the ventral midline and just posterior to the left pectoral fin, and an ECG was acquired and processed as previously described (Gilbert et al., 2019). The fish were then given an intraperitoneal injection of 1.2 mg/kg atropine sulphate and 4 μg kg−1 isoproterenol in a total volume of 1 mL kg−1 0.8% NaCl solution to stimulate their fHmax. Once the heart rate stabilized (~20 min), the anaesthetic bath was warmed (n = 12) or cooled (n = 8) from 5 and 10°C, respectively, at a rate of 5°C h−1 in 1°C increments every 12 min using a drop-in coil heater–chiller (Isotemp II, Fisher Scientific, Hampton, USA), and a flow-through aquarium chiller (Tr15, Teco, Ravenna, ITA). The experiment continued until the heartbeat became arrhythmic or the bath began to freeze at which point the fish was euthanized with an overdose of anaesthetic (150 mg/L buffered TMS) followed by spinal pithing. The ECG was analyzed using automated heartbeat detection as in Gilbert et al. (2019). The temperature at the first Arrhenius break point (TwarmAB), peak fHmax, temperature at peak fHmax (Tpeak) and temperature at arrhythmia (Tarr) were identified for each individual as previously described (Casselman et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2015; Hansen et al., 2016). We also identified an Arrhenius break point temperature (TcoldAB) for each fish that was acutely cooled from 10°C. Briefly, Arrhenius break point temperatures were identified using a segmented linear regression and indicate a temperature at which there is a notable transition in the thermal sensitivity of a given rate with further warming or cooling. Tpeak and peak fHmax are the temperature and fH at which fHmax ceased to increase or began decreasing with further warming and thus indicate the fHmax and temperature at which a cardiac performance limitation occurred. Tarr is the temperature at which the heart began skipping beats (became irregular), thus indicating severe cardiac dysfunction.

Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in R Studio (R Core Team, 2014) except for the segmented regression analysis which, along with all data presentation, was done using Prism v.8.3 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, USA). To account for allometric scaling, ṀO2Max, ṀO2Min and ṀO2 during acute warming were adjusted to a common body mass by summing the residual values from the respective log(ṀO2) vs. log(mass) linear relationship with the predicated value at the average mass (0.71 kg). This adjustment was done prior to all other analyses. Based on relationships identified in previous studies (e.g. Eliason et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2015), the effect of test temperature on ṀO2Max and ṀO2Min was examined using linear and second-order polynomial models and the model with the lowest AICc value was presented. The effect of temperature (fixed effect) on ṀO2 and fHmax during acute warming was assessed using linear mixed effects models (LMMs; lme4 package; Bates et al, 2015) with Fish ID included as a random factor to account for the fact that multiple measurements were made on each individual. The fHmax model was restricted to values recorded below an individual’s Tpeak. Test statistics for LMM were generated using Satterthwaite’s degrees of freedom method in the ‘lmertest’ package (Kuznetsova et al., 2017) and marginal and condition correlation coefficients were calculated using the ‘MuMIn’ package (Barton and Barton, 2015). The normality of model residuals was confirmed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Arrhenius break point temperatures were determined during cooling and warming as previously described (Casselman et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2015). All data are presented as mean ± SEM unless otherwise noted and α = 0.05.

Results

Respirometry and CTMax

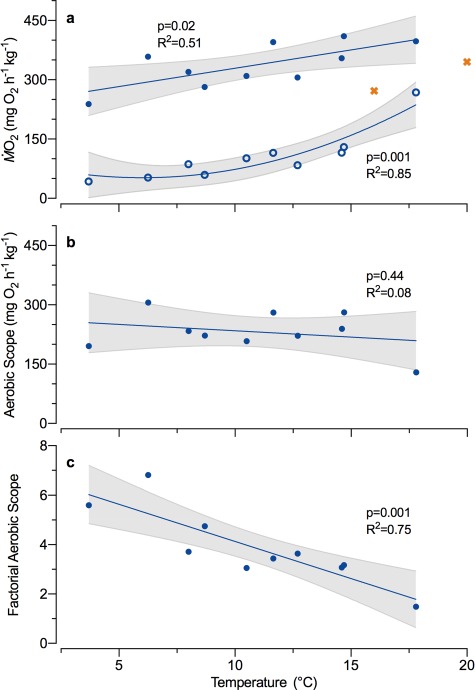

River temperatures ranged from 8.9 to 14.5°C (mean ± SD: 11.0 ± 1.4°C; recorded every 15 min) during the period when fish were captured for the respirometry experiments. Arctic char were acutely brought (2°C h−1) to their test temperature (T) before being chased to fatigue, which lasted 4.4 ± 0.2 min, independent of temperature (f1,10 = 0.49, P = 0.50, R2 = 0.05). ṀO2Max increased linearly with increasing test temperature (Fig. 2a; Eq. 1, f1,8 = 8.3, P = 0.02, R2 = 0.51), while ṀO2Min increased exponentially (Fig. 2a; Eq. 2, f2,7 = 19.9, P = 0.001, R2 = 0.85). Even so, AAS did not change significantly with increased temperature (Fig. 2b; Eq. 3, f1,8 = 0.65, P = 0.44, R2 = 0.08), whereas FAS decreased markedly (Fig. 2c; Eq. 4, f1,8 = 23.6, P = 0.001, R2 = 0.75).

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

Figure 2.

The effect of environmentally relevant temperatures on (a) minimum (ṀO2Min; open circles; n = 10) and maximum oxygen uptake (ṀO2Max; closed circles; n = 12) and aerobic scope of migratory Arctic char following a chase to exhaustion and air exposure. (b) Absolute aerobic scope (AAS) and (c) factorial aerobic scope (FAS). Two individuals at warm temperatures died after being exhausted (orange ‘x’) and were excluded from all regression analyses. A linear model and a second-order polynomial model were compared for each variable. The model with the lowest AICc is presented (blue lines) with its 95% confidence interval (shaded area), R2 and P value.

Importantly, two of the three fish exercised to exhaustion above 15°C died during recovery and had a lower ṀO2Max than would be predicted based on the linear model for the remaining fish (Fig. 2a). The individual that did recover after being chased at > 15°C exhibited the lowest AAS and CTMax and had the highest blood lactate concentration (15.1 mM) post-CTMax. Whether this elevated lactate was a result of the notably elevated ṀO2Min (Figs 1a and 2) or a more severe degree of exhaustion is unclear.

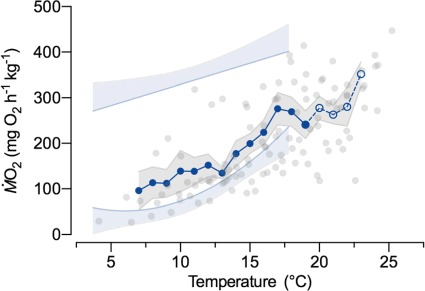

Acute warming following the post-chase recovery period doubled ṀO2 (LMM: f1,8.9 = 145.1, P < 0.001, marginal R2 = 0.50, conditional R2 = 0.83) from 138.8 ± 37.2 mg O2 h kg−1 at 10°C to 277.7 ± 22.0 mg O2 h kg−1 at 20°C (Q10 = 2.0). Peak ṀO2 during acute warming was 319.1 ± 33.6 mg O2 h kg−1 (at 19.8 ± 1.1°C), a value similar to that measured immediately after exhaustive exercise at warm temperature (Figs 2a and 3). Likewise, a similar ṀO2 (291.1 ± 42.7 mg O2 h kg−1) also was seen immediately prior to reaching CTMax (23.0 ± 0.6°C; range 19.0 to 25.2; Fig. 5).

Figure 3.

Oxygen uptake (ṀO2) of anadromous Arctic char during acute warming to loss of equilibrium (CTMax). Individual ṀO2 values at their measured temperatures (grey circles; n = 8 individuals and 111 data points) and mean ± sem values in 1°C bins (blue circles and grey shading) are presented. Mean values were calculated at all points where data were available for three or more individuals. The dashed line indicates temperatures where individuals were removed after reaching CTMax. For reference, the models for maximum ṀO2 and ṀO2Min (Fig. 1) are presented with their upper or lower 95% confidence intervals, respectively (light blue lines with shaded areas).

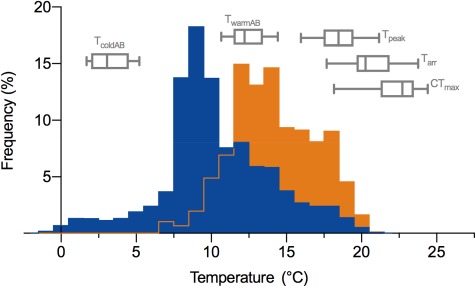

Figure 5.

Transition temperatures for maximum heart rate (fHmax) and the critical thermal maximum (CTMax) for anadromous Arctic char relative to frequency distributions for water temperatures during their upriver migration. Arrhenius break point temperatures (cooling: TcoldAB warming: TwarmAB) and temperatures at peak fHmax (Tpeak), onset of arrhythmia (Tarr) and loss of equilibrium (CTMax) are shown relative to the average (blue) and warmest (orange; Gilbert et al. 2016) river temperature frequencies recorded during upriver migrations in the Kitikmeot region of Nunavut, Canada. River temperatures were compiled for four rivers from past (Gilbert et al. 2016) and ongoing fisheries research (M.J.H.G. and L.N.H. unpublished data). Boxes represent the median and interquartile range and whiskers indicate the 5th and 95th percentile of data.

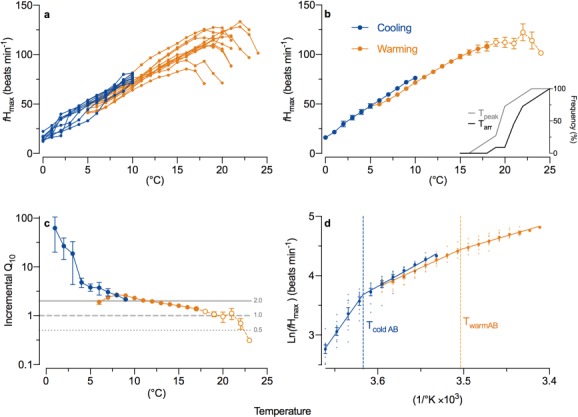

f Hmax and cardiac thermal tolerance

River temperatures ranged from 9.7 to 12.4°C (mean: 10.6 ± 0.24) at the site of capture of fish used for the cardiac thermal tolerance experiments. fHmax in Arctic char acutely transferred to 5°C was 47.7 ± 1.3 beats min−1. Acute warming of these fish increased their fHmax (LMM: f1,9.6 = 807.5, P < 0.001, marginal R2 = 0.92, conditional R2 = 0.98), attaining a peak fHmax of 115.4 ± 4.7 beats min−1 at 19.4 ± 0.5°C (Tpeak; Figs 4 and 5). Above Tpeak, fHmax declined to 99.0 ± 5.9 beats min−1 and became arrhythmic at 21.4 ± 0.5°C (Tarr; Figs 4 and 5) before the experiment was terminated. The temperature of the first Arrhenius break point in fHmax during warming (TwarmAB) was 12.5 ± 0.3°C (Fig. 4a and b), which was similar to common ambient river temperatures (Fig. 5). The instantaneous Q10 for fHmax decreased progressively with warming (Fig. 4c), falling below 2.0 at ~ 11°C; the Q10 of 1.0 at ~ 19°C indicated that, on average, fHmax had peaked or plateaued (Fig. 4c). With acute cooling from 10 to 0°C, fHmax progressively decreased from 76.3 ± 1.3 beats min−1 to 16.1 ± 1.2 beats min−1 (LMM: f1,7.0 = 1273.9, P < 0.001, marginal R2 = 0.93 conditional R2 = 0.97) and exhibited a clear break point at ~ 3.3 ± 0.5°C (Fig. 4d), below which the thermal dependence of fHmax increased sharply with an instantaneous Q10 > 10 (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4.

Maximum heart rate (fHmax) of anadromous Arctic char during acute warming from 5°C (orange; n = 12) and cooling from 10°C (blue; n = 8) as (a) individual and (b) average responses. The cumulative proportion of individuals that reached their temperature at peak fHmax (Tpeak) and arrhythmia (Tarr) are inset (b). The thermal sensitivity of fHmax is shown using (c) the temperature coefficient (Q10) calculated over 2°C increments, with reference lines indicating rates of change that would correspond to a doubling (2.0), plateau (1.0) or halving (0.5) of fHmax over 10°C and (d) an Arrhenius plot of fHmax showing the first Arrhenius break points during warming (TwarmAB) and cooling (TcoldAB). Averaged data (b–d) are presented ± sem and dashed connecting lines with open circles indicate temperatures where some individuals were removed from the analysis following arrhythmia.

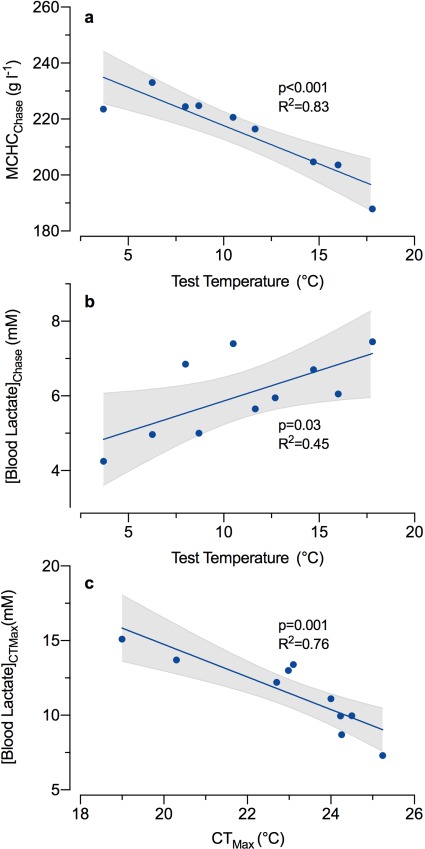

Blood properties

The MCHC decreased (Fig. 6a; f1,7 = 33.3, P < 0.001, R2 = 0.83) and blood lactate concentration increased (Fig. 6b; f1,8 = 6.6, P = 0.03, R2 = 0.45) with test temperature when measured immediately after Arctic char were chased to exhaustion. Blood lactate measured immediately after CTMax was negatively correlated with CTMax (Fig. 6c; f1,8 = 21.2, P = 0.001, R2 = 0.76). Additional blood parameters were correlated with each other, but not with the test temperature or CTMax (Fig. S2).

Figure 6.

Correlations between blood properties and either the test temperature or the critical thermal maximum (CTMax). Blood was drawn immediately following the chase to exhaustion (a and b) or immediately after fish lost equilibrium at their CTMax (c). Significant relationships were identified through a pairwise Spearmen’s correlation analysis (α = 0.05; Fig. S2). Relationships for mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration (MCHC; a) and blood lactate (b and c) are shown with their corresponding linear model (solid line) and with 95% confidence intervals (dashed line).

Discussion

Anadromous Arctic char can encounter a broad range of temperatures from ~ 0 to 21°C during their physically demanding, upriver migrations in the Canadian Arctic (Fig. 5; Gilbert et al., 2016) and even lower when at sea (Harris et al., 2020). Here we show that wild migrating Arctic char can impressively maintain absolute aerobic scope and a high regular heart rate over a large proportion (~4–16°C) of this thermal range. However, factorial aerobic scope (FAS), their ability to recover from exhaustive exercise and their fHmax can become critically limited > 16°C, temperatures that are well within current extremes (Fig. 5). Moreover, and unexpectedly, fHmax was greatly depressed with acute cooling to 0°C. As we discuss below, these traits may be intimately linked to the need for Arctic char to repeatedly perform prolonged swimming bouts over a wide range of temperatures in order to complete their migrations and successfully reproduce. Importantly, our findings were made possible by the use of innovative mobile research infrastructure (Fig. S1). Thus, the present study demonstrates the critical importance of such infrastructure and logistical support in any effort to understand pressing conservation and management issues in remote Arctic locations.

Cold performance

Early research on cold-adapted fish species suggested that they may exhibit elevated metabolic rates at cold temperatures to allow elevated growth and activity when compared to related species that were not cold-adapted (Scholander et al., 1953; Wohlschlag, 1960). This idea, which was termed ‘metabolic cold adaptation’, has largely been disproven and currently has limited support (Holeton, 1973; Holeton, 1974; Steffensen et al., 1994; Steffensen, 2002; White et al., 2012). Indeed, when Holeton (1973) tested this hypothesis on wild juvenile Arctic char in the Canadian Arctic, he found that their resting ṀO2 was no higher than would be predicted for more temperate salmonids despite the Arctic char being adapted and acclimatized to a cold environment. However, Holeton’s measurements of resting ṀO2 measurements at ambient temperatures (2°C) were technically limited by available equipment, facilities and technology. Although our ṀO2 data do not extend to 0°C, our ṀO2 data for cool temperatures similarly indicate that Arctic char do not exhibit elevated metabolism when compared with other salmonids (e.g. Hvas et al., 2017). Instead, fHmax clearly and sharply declined (high Q10) at < 3.3°C, suggesting the potential for Arctic char to undergo metabolic rate suppression rather elevation metabolism at frigid temperatures. Further, we propose this transition in fHmax may be part of a suite of behavioural and physiological overwintering strategies that conserve energy during a period of limited food availability. Indeed, other species display an active depression of metabolic rate (Guppy and Withers, 1999), fasting and suppression of activity (Speers-Roesch et al., 2018). However, as we did not directly characterize acute or prolonged responses of ṀO2 to cold temperature (<3°C), this possibility remains to be tested.

While the observed limitation in fHmax at cold temperatures could be part of an adaptive energy conservation strategy, it would likely limit maximum cardiac output and thus aerobic exercise capacity. This cold limitation could, in turn, impact performance during demanding activities such as river migrations or diving down to frigid waters to forage. Indeed, telemetry data suggest that dives to colder, deeper ocean waters are typically very brief (Spares et al., 2012; Harris et al., 2020). If this is indeed an issue, cold acclimation could help mitigate the observed effects of acute cold exposure. Fish in the present study were presumably acclimated to near the ambient river temperatures at which they were caught (~11°C), while Arctic char at sea (e.g. ~ 5–8°C, Harris et al., 2020) or overwintering (e.g. 0.5–2°C; Mulder et al., 2018) would be acclimated to colder water. Indeed, the only other comparable study of fHmax, which focused on ocean-caught Arctic char, did not find such a pronounced change in fHmax at cold temperatures (Hansen et al., 2016). Furthermore, cold acclimation has previously been shown to increase intrinsic and maximum fH in many fishes, which helps counteract rate limitations inherently associated with cold exposure (Aho and Vornanen, 2001; Drost et al., 2016; Eliason and Anttila, 2017).

Warm performance

While debate continues over the ecological relevance of CTMax and similar acute lethal thermal tolerance measures (Pörtner and Peck, 2010; Sunday et al., 2011), such metrics remain useful, relative indicators of whole-organism heat tolerance and are unarguably the ceiling for thermal performance (Sandblom et al., 2016). Previous measures of CTMax in hatchery-reared (~0.02–0.05 kg) European Arctic char parr (e.g. ~ 26–28°C; Baroudy and Elliott, 1994; Anttila et al., 2015) are significantly higher than CTMax for adults in the present study (23°C). In contrast, CTmax for adult Arctic char (0.7 kg) reared in a marine aquaculture in eastern Canada and acclimated to ~ 10°C (23°C; Penney et al., 2014) was identical to the present result. By comparison, adult Arctic cod, a classic polar stenotherm and important food source for Arctic char, have a much lower CTMax (~15–17°C, Drost et al., 2016), whereas the CTMax of adult rainbow trout (0.3–0.7 kg) and Atlantic salmon (0.7 kg), both temperate relatives of Arctic char, is notably higher (~26–27°C; Ekström et al., 2014; Penney et al., 2014; Gilbert et al., 2019). In the present study, elevated blood lactate was associated with a lower CTMax, indicating that anaerobic stress prior to or during acute warming may subsequently decrease heat tolerance, which could be particularly important for exercising (migrating)fish.

Sub-lethal thermal limitations to physiological performances, such as a collapse in aerobic scope and heart rate, or cardiac arrhythmia, are arguably of greater ecological relevance than acutely lethal limitations because they occur at lower, more commonly encountered temperatures (Fig. 4). Penney et al. (2014) monitored fH and ṀO2 in Arctic char during acute warming and found an identical peak fH to that found here (115 beats min−1). This similarity suggests that acutely warmed adult Arctic char reach their physiological maximum fH prior to CTMax, leaving little to no scope for fH available to support further warming. At 10°C the same study (Penney et al., 2014) found that resting fH was ~ 44 beats min−1 whereas fHmax at 10°C was ~ 74 beats min−1 in the present study, highlighting a significant scope to increase fH at cooler temperatures. Despite the similarities, Penney et al. (2014) found that the peak ṀO2 achieved during warming was only 223 mg O2 h kg−1 compared to ~ 319 mg O2 h kg−1 in the present study, which may indicate a loss of aerobic performance following captive rearing or domestication, as found in Atlantic salmon (Zhang et al., 2016).

Hansen et al. (2016) examined cardiac heat tolerance in sea run char from Greenland and found that Twarmab, Tpeak, Tarr and peak fHmax were only 7.5, 12.8, 15.2 and 61.8 beats min−1, respectively. All of these thermal performance indicators are all markedly lower (Twarmab: −5.0°C Tpeak: −6.6°C, Tarr: −6.2°C and peak fHmax: −53.6 beats min−1) than in the present study, despite similar methodology and fish size. There were, however, key differences between the studies including the life history period (marine vs. upstream fall migrating), fish provenance (Greenland vs. central Canadian Arctic) and possibly acclimation temperatures (~7 vs ~ 11°C). The most parsimonious explanation for these differences is the potential for either thermal acclimation or thermal adaptation among populations (as discussed below).

Gilbert and Tierney (2018) found that acutely warmed wild smolts and lab-reared juvenile Arctic char (~0.1 kg) maintained swimming performance up to 21°C, but their recovery was impaired above > 20°C. This impaired recoverability was associated with highly elevated blood lactate concentrations, which can be indicative o increased anaerobic demand and metabolic acidosis. Here, blood lactate levels also increased with temperature and we observed impaired recoverability following exhaustive exercise albeit in much larger animals at an even lower temperature (>15–16°C). We measured blood lactate immediately following chasing although lactate release from tissues can continue over a longer time course (Milligan, 1996). As such, our results could be a product of increased rate of lactate release into the blood rather than elevated anaerobic metabolism. However, we also observed a decrease in MCHC with increased temperature, which is indicative of red blood cell swelling in response to metabolic acidosis (Nikinmaa et al., 1987). Gilbert and Tierney (2018) also found that a handling challenge in large migrating adult Arctic char (~4 kg) resulted in an increase in reflex impairment above 12°C, which was associated with early mortality. These post-handling impairments were particularly severe (>50%) above 15°C, which is lower than their observations in smolts (>20°C) and consistent with results for adults in the present study. Together these data suggest that access to cold-water refugia in lakes or pools may be critical for recovery if they encounter and can swiftly pass through warm temperatures during their up-river migration.

Arctic char are clearly more heat tolerant than classically stenothermal polar fishes, likely as a result of the extreme thermal variability they can encounter over the course of their lives (Janzen, 1967; Verde et al., 2008). Nonetheless, they are among the least heat-tolerant salmonids (Elliott and Elliott, 2010; Penney et al., 2014; Gilbert and Tierney, 2018), yet they are already encountering temperatures warm enough to impair vital physiological functions and impact survival. Given that fish only recruit maximum physiological performances (e.g. MO2Max and fHmax) during demanding activities (e.g. navigating rapids) and operate at a sub-maximal performance level most of the time, further research is needed to examine temperature effects on sub-maximal performances such as routine swimming, growth, feeding and digestion.

Future directions: examining sources of variation in Arctic char thermal physiology

The inter-study differences in thermal physiology highlighted above suggest that thermal history, ontogeny, and genetic background likely all contribute to thermal performance in Arctic char in a similar manner to other salmonids. For example, in Atlantic salmon warm acclimation can markedly increase cardiac thermal tolerance (Anttila et al., 2014). However, comparable knowledge for Arctic char is almost completely lacking. Ontogeny also has a pronounced effect on thermal physiology (Elliott and Elliott, 2010; Portner et al., 2017; Hines et al., 2019). Such effects have not been well characterized in Arctic char but likely contribute to incongruences between the present and past studies (see Larsson, 2005; Larsson and Berglund, 2005; Mortensen et al., 2007; Mulder et al., 2019; Harris et al. 2020).

In temperate salmonids (e.g. Oncorhynchus spp.), thermal tolerance tends to be higher in strains from warm habitats (Rodnick et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2015; Verhille et al., 2016; Poletto et al., 2017). Based on the current literature, European Arctic char may appear more thermally tolerant than Arctic char from Greenland and the Canadian Arctic. European Arctic char are from a different glacial lineage than Greenlandic and northern Canadian Arctic char and have therefore evolved independently for > 250 000 years (Brunner et al., 2001; Moore et al., 2015). This isolation may provide a genetic basis for regional differences in thermal physiology. Even within a watershed, the cardiorespiratory thermal performance curves of sockeye salmon (O. nerka) appear locally adapted to the conditions they encounter during their upriver migration (Eliason et al., 2011). While a recent study has shown that Kitikmeot Arctic char exhibit genetic differences among populations that are consistent with the hypothesis that they may be locally adapted (Moore et al., 2017), no study to date has examined this at the phenotypic level.

Conclusions: thermal barriers to migration

Extreme heat events have repeatedly been shown to impose thermal barriers on the migration of temperate salmonids (Baisez et al., 2011; Martins et al., 2011; Hinch et al., 2012; Martins et al., 2012) by critically impairing physiological performances (Cooke et al., 2006; Farrell et al., 2008; Farrell, 2009; Eliason et al., 2011). Here we clearly show that, like these temperate salmonids, migrating Arctic char experience limitations in cardiac performance, FAS and recoverability at water temperatures that already occur during their migrations in some Arctic rivers (Fig. 4; Gilbert et al., 2016). Such limitations can critically impair migration, and they are only going to become more common as the Canadian Arctic is among the most rapidly warming regions on our planet (Zhang et al., 2019). The consequences of migration failure and associated reductions in fitness may be particularly dire in regions like the Kitikmeot, NU, where Arctic char are heavily harvested and relied upon as both a subsistence and economic resource (Day and Harris, 2013; Roux et al., 2019). As such, understanding and mitigating the impacts of extreme temperature events should be an urgent priority for fisheries managers, researchers and conservationists alike.

Funding

This research was funded by Polar Knowledge Canada through the Science and Technology Program (2017) and the Northern Scientific Training Program (M.J.H.G.) as well as by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council through Discovery and Canada Research Chair awards (A.P.F.) and an Alexander Graham Bell Canada Graduate Scholarship (M.J.H.G.).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the Ekaluktutiak Hunters and Trappers Organization (EHTO) and the community of Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, for their support in completing this work. We would also like to thank Paul Waechter, Helen Drost and Arctic Research Foundation staff for their contributions to the development, setup and maintenance of the mobile laboratory, as well as Angulalik Pedersen and other Polar Knowledge Canada (POLAR) staff who provided logistical assistance.

References

- Aho E, Vornanen M (2001) Cold acclimation increases basal heart rate but decreases its thermal tolerance in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). J Comp Physiol B 171: 173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anttila K, Couturier CS, Øverli Ø, Johnsen A, Marthinsen G, Nilsson GE, Farrell AP (2014) Atlantic salmon show capability for cardiac acclimation to warm temperatures. Nat Commun 5: 4252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anttila K, Lewis M, Prokkola JM, Kanerva M, Seppanen E, Kolari I, Nikinmaa M (2015) Warm acclimation and oxygen depletion induce species-specific responses in salmonids. J Exp Biol 218: 1471–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baisez A, Bach J-M, Leon C, Parouty T, Terrade R, Hoffmann M, Laffaille P (2011) Migration delays and mortality of adult Atlantic salmon Salmo salar en route to spawning grounds on the River Allier, France. Endanger Species Res 15: 265–270. [Google Scholar]

- Baroudy E, Elliott J (1994) The critical thermal limits for juvenile Arctic charr Salvelinus alpinus. J Fish Biol 45: 1041–1053. [Google Scholar]

- Barton K., Barton M. K. (2015). Package ‘MuMIn’. Version 1, 18.

- Bates D., Maechler M., Bolker B.. Walker S. (2015). Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4. J Stat Softw 67: 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Brunner PC, Douglas MR, Osinov A, Wilson CC, Bernatchez L (2001) Holarctic phylogeography of Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus L.) inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences. Evol 55: 573–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casselman MT, Anttila K, Farrell AP (2012) Using maximum heart rate as a rapid screening tool to determine optimum temperature for aerobic scope in Pacific salmon Oncorhynchus spp. J Fish Biol 80: 358–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabot D, Steffensen JF, Farrell AP (2016) The determination of standard metabolic rate in fishes. J Fish Biol 88: 81–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Snow M, Lawrence CS, Church AR, Narum SR, Devlin RH, Farrell AP (2015) Selection for upper thermal tolerance in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss Walbaum). J Exp Biol 218: 803–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark T, Eliason E, Sandblom E, Hinch S, Farrell A (2008) Calibration of a hand-held haemoglobin analyser for use on fish blood. J Fish Biol 73: 2587–2595. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke SJ, Hinch SG, Crossin GT, Patterson DA, English KK, Shrimpton JM, Kraak GVD, Farrell AP (2006) Physiology of individual late-run Fraser River sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) sampled in the ocean correlates with fate during spawning migration. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 63: 1469–1480. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke SJ, et al. (2012) Conservation physiology in practice: how physiological knowledge has improved our ability to sustainably manage Pacific salmon during up-river migration. Philos T R Soc B 367: 1757–1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke SJ, O’Connor CM (2010) Making conservation physiology relevant to policy makers and conservation practitioners. Conserv Lett 3: 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke SJ, Sack L, Franklin CE, Farrell AP, Beardall J, Wikelski M, Chown SL (2013) What is conservation physiology? Perspectives on an increasingly integrated and essential science(dagger). Conserv Physiol 1: cot001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day AC, Harris LN (2013) Information to Support an Updated Stock Status of Commercially Harvested Arctic Char (Salvelinus alpinus) in the Cambridge Bay region of Nunavut, 1960–2009. Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, Ottawa, ON.

- DFO (2012) Temperature threshold to define management strategies for Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) fisheries under environmentally stressful conditions. Can Sci Advis Sec Sci Advis Rep 2012: 17. [Google Scholar]

- Drost HE, Lo M, Carmack EC, Farrell AP (2016) Acclimation potential of Arctic cod (Boreogadus saida) from the rapidly warming Arctic Ocean. J Exp Biol 219: 3114–3125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekström A, Jutfelt F, Sandblom E (2014) Effects of autonomic blockade on acute thermal tolerance and cardioventilatory performance in rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss. J Therm Biol 44: 47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliason EJ, Anttila K (2017) Temperature and the cardiovascular system In Gamperl AK, Gillis TE, Farrell AP, Brauner CJ, eds, The Cardiovascular System: Development, Plasticity and Physiological Responses Vol 36, Academic Press Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, pp. 235–297. [Google Scholar]

- Eliason EJ, Clark TD, Hague MJ, Hanson LM, Gallagher ZS, Jeffries KM, Gale MK, Patterson DA, Hinch SG, Farrell AP (2011) Differences in thermal tolerance among sockeye salmon populations. Science 332: 109–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliason EJ, Clark TD, Hinch SG, Farrell AP (2013) Cardiorespiratory collapse at high temperature in swimming adult sockeye salmon. Conserv Physiol 1: cot008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott J, Elliott J (2010) Temperature requirements of Atlantic salmon Salmo salar, brown trout Salmo trutta and Arctic charr Salvelinus alpinus: predicting the effects of climate change. J Fish Biol 77: 1793–1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell A, Hinch S, Cooke S, Patterson D, Crossin G, Lapointe M, Mathes M (2008) Pacific salmon in hot water: applying aerobic scope models and biotelemetry to predict the success of spawning migrations. Physiol Biochem Zool 81: 697–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell A, Lee C, Tierney K, Hodaly A, Clutterham S, Healey M, Hinch S, Lotto A (2003) Field-based measurements of oxygen uptake and swimming performance with adult Pacific salmon using a mobile respirometer swim tunnel. J Fish Biol 62: 64–84. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AP. (2009) Environment, antecedents and climate change: lessons from the study of temperature physiology and river migration of salmonids. J Exp Biol 212: 3771–3780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AP. (2016) Pragmatic perspective on aerobic scope: peaking, plummeting, pejus and apportioning. J Fish Biol 88: 322–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galappaththi EK, Ford JD, Bennett EM, Berkes F (2019) Climate change and community fisheries in the arctic: a case study from Pangnirtung, Canada. J Environ Manag 250: 109534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert MJH, Donadt CR, Swanson HK, Tierney KB (2016) Low annual fidelity and early upstream migration of anadromous Arctic char in a variable environment. Trans Am Fish Soc 145: 931–942. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert MJH, Rani V, McKenzie SM, Farrell AP (2019) Autonomic cardiac regulation facilitates acute heat tolerance in rainbow trout: in situ and in vivo support. J Exp Biol 222 1–10 doi: 10.1242/jeb.194365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert MJH, Tierney KB (2018) Warm northern river temperatures increase post-exercise fatigue in an Arctic migratory salmonid but not in a temperate relative. Funct Ecol 32: 687–700. [Google Scholar]

- Godiksen JA, Power M, Borgstrøm R, Dempson JB, Svenning MA (2012) Thermal habitat use and juvenile growth of Svalbard Arctic charr: evidence from otolith stable oxygen isotope analyses. Ecol Freshw Fish 21: 134–144. [Google Scholar]

- Guppy M, Withers P (1999) Metabolic depression in animals: physiological perspectives and biochemical generalizations. Biol Rev 74: 1–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyselman EC. (1994) Fidelity of anadromous Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus) to Nauyuk Lake, N.W.T., Canada. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 51: 1927–1934. [Google Scholar]

- Harris LN, Yurkowski DJ, Gilbert MJH, Else BGT, Duke PJ, Tallman RF, Fisk AT, Moore J-S (2020) Depth and temperature preference of anadromous Arctic char, Salvelinus alpinus, in the Kitikmeot Sea, a shallow and low salinity area of the Canadian Arctic. Mar Ecol Progr Ser 634: 175–197. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen AK, Byriel DB, Jensen MR, Steffensen JF, Svendsen MBS (2016) Optimum temperature of a northern population of Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus) using heart rate Arrhenius breakpoint analysis. Polar Biol 40: 1063–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Hinch S, Cooke S, Farrell A, Miller K, Lapointe M, Patterson D (2012) Dead fish swimming: a review of research on the early migration and high premature mortality in adult Fraser River sockeye salmon Oncorhynchus nerka. J Fish Biol 81: 576–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines CW, Fang Y, Chan VKS, Stiller KT, Brauner CJ, Richards JG (2019) The effect of salinity and photoperiod on thermal tolerance of Atlantic and coho salmon reared from smolt to adult in recirculating aquaculture systems. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol 230: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holeton G. (1973) Respiration of arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus) from a high arctic lake. J Fish Board Can 30: 717–723. [Google Scholar]

- Holeton GF. (1974) Metabolic cold adaptation of polar fish: fact or artefact? Physiol Zool 47: 137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Hvas M, Folkedal O, Imsland A, Oppedal F (2017) The effect of thermal acclimation on aerobic scope and critical swimming speed in Atlantic salmon Salmo salar. J Exp Biol. 220: 2757–2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janzen DH. (1967) Why mountain passes are higher in the tropics. Am Nat 101: 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson L. (1989) The anadromous arctic charr, Salvelinus alpinus, of Nauyuk Lake, NWT, Canada. Physiol Ecol Jap 1: 201–227. [Google Scholar]

- Klemetsen A, Amundsen PA, Dempson JB, Jonsson B, Jonsson N, O’Connell MF, Mortensen E (2003) Atlantic salmon Salmo salar L., brown trout Salmo trutta L. and Arctic charr Salvelinus alpinus (L.): a review of aspects of their life histories. Ecol Freshw Fish 12: 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB (2017) lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J Stat Softw 82: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson S. (2005) Thermal preference of Arctic charr, Salvelinus alpinus, and brown trout, Salmo trutta–implications for their niche segregation. Environ Biol Fish 73: 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson S, Berglund I (2005) The effect of temperature on the energetic growth efficiency of Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus L.) from four Swedish populations. J Therm Biol 30: 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mallory ML, Gilchrist HG, Janssen M, Major HL, Merkel F, Provencher JF, Strøm H (2018) Financial costs of conducting science in the Arctic: examples from seabird research. Arctic Sci 4: 624–633. [Google Scholar]

- Martins EG, Hinch SG, Patterson DA, Hague MJ, Cooke SJ, Miller KM, Lapointe MF, English KK, Farrell AP (2011) Effects of river temperature and climate warming on stock-specific survival of adult migrating Fraser River sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka). Glob Change Biol 17: 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Martins EG, Hinch SG, Patterson DA, Hague MJ, Cooke SJ, Miller KM, Robichaud D, English KK, Farrell AP, Jonsson B (2012) High river temperature reduces survival of sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) approaching spawning grounds and exacerbates female mortality. Can J Fisher Aquat Sci 69: 330–342. [Google Scholar]

- Milligan CL. (1996) Metabolic recovery from exhaustive exercise in rainbow trout. Comp Biochem Phys A 113: 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Mochnacz NJ, Kissinger BC, Deslauriers D, Guzzo MM, Enders EC, Anderson WG, Docker MF, Isaak DJ, Durhack TC, Treberg JR (2017) Development and testing of a simple field-based intermittent-flow respirometry system for riverine fishes. Conserv Physiol 5: cox048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore J-S, Bajno R, Reist JD, Taylor EB (2015) Post-glacial recolonization of the North American Arctic by Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus): genetic evidence of multiple northern refugia and hybridization between glacial lineages. J Biogeogr 42: 2089–2100. [Google Scholar]

- Moore J-S, Harris LN, Kessel ST, Bernatchez L, Tallman RF, Fisk AT (2016) Preference for nearshore and estuarine habitats in anadromous Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus) from the Canadian high Arctic (Victoria Island, Nunavut) revealed by acoustic telemetry. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 73: 1434–1445. [Google Scholar]

- Moore JS, Harris LN, Le Luyer J, Sutherland BJG, Rougemont Q, Tallman RF, Fisk AT, Bernatchez L (2017) Genomics and telemetry suggest a role for migration harshness in determining overwintering habitat choice, but not gene flow, in anadromous Arctic Char. Mol Ecol. 26: 6784–6800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen A, Ugedal O, Lund F (2007) Seasonal variation in the temperature preference of Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus). J Therm Biol 32: 314–320. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder IM, Morris CJ, Dempson JB, Fleming IA, Power M (2018) Overwinter thermal habitat use in lakes by anadromous Arctic char. Can J Fisher Aquat Sci 75: 2343–2353. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder IM, Morris CJ, Dempson JB, Fleming IA, Power M (2019) Marine temperature and depth use by anadromous Arctic Char correlates to body size and diel period. Can J Fisher Aquat Sci. doi: 10.1139/cjfas-2019-0097 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nikinmaa M, Steffensen JF, Tufts BL, Randall DJ (1987) Control of red cell volume and pH in trout: effects of isoproterenol, transport inhibitors, and extracellular pH in bicarbonate/carbon dioxide-buffered media. J Exper Zool 242: 273–281. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson DA, Cooke SJ, Hinch SG, Robinson KA, Young N, Farrell AP, Miller KM (2016) A perspective on physiological studies supporting the provision of scientific advice for the management of Fraser River sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka). Conserv Physiol 4: cow026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penney CM, Nash GW, Gamperl AK (2014) Cardiorespiratory responses of seawater-acclimated adult Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus) and Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) to an acute temperature increase. Can J Fisher Aquat Sci 71: 1096–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Poletto JB, Cocherell DE, Baird SE, Nguyen TX, Cabrera-Stagno V, Farrell AP, Fangue NA (2017) Unusual aerobic performance at high temperatures in juvenile Chinook salmon, Oncorhynchus tshawytscha. Conserv Physiol 5: cow067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portner HO, Bock C, Mark FC (2017) Oxygen- and capacity-limited thermal tolerance: bridging ecology and physiology. J Exp Biol 220: 2685–2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pörtner HO, Peck MA (2010) Climate change effects on fishes and fisheries: towards a cause-and-effect understanding. J Fish Biol 77: 1745–1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2014) R: a language and environment for statistical computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. http://www.R-project.org/.

- Rikardsen AH, Elliott DJM, Dempson JB, Sturlaugsson J, Jensen AJ (2007) The marine temperature and depth preferences of Arctic charr (Salvelinus alpinus) and sea trout (Salmo trutta), as recorded by data storage tags. Fisher Oceanogr 16: 436–447. [Google Scholar]

- Rodnick KJ, Gamperl AK, Lizars KR, Bennett MT, Rausch RN, Keeley ER (2004) Thermal tolerance and metabolic physiology among redband trout populations in south-eastern Oregon. J Fish Biol 64: 310–335. [Google Scholar]

- Roux M-J, Tallman RF, Martin ZA (2019) Small-scale fisheries in Canada’s Arctic: combining science and fishers knowledge towards sustainable management. Mar Policy 101: 177–186. [Google Scholar]

- Roux MJ, Tallman RF, Lewis CW (2011) Small-scale Arctic charr Salvelinus alpinus fisheries in Canada’s Nunavut: management challenges and options. J Fish Biol 79: 1625–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandblom E, Clark TD, Gräns A, Ekström A, Brijs J, Sundstrom LF, Odelström A, Adill A, Aho T, Jutfelt F (2016) Physiological constraints to climate warming in fish follow principles of plastic floors and concrete ceilings. Nat Commun 7: 11447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholander P, Flagg W, Walters V, Irving L (1953) Climatic adaptation in arctic and tropical poikilotherms. Physiol Zool 26: 67–92. [Google Scholar]

- Spares AD, Stokesbury MJW, O’Dor RK, Dick TA (2012) Temperature, salinity and prey availability shape the marine migration of Arctic char, Salvelinus alpinus, in a macrotidal estuary. Mar Biol 159: 1633–1646. [Google Scholar]

- Speers-Roesch B, Norin T, Driedzic WR (2018) The benefit of being still: energy savings during winter dormancy in fish come from inactivity and the cold, not from metabolic rate depression. Proc Biol Sci 285. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2018.1593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffensen J, Bushnell P, Schurmann H (1994) Oxygen consumption in four species of teleosts from Greenland: no evidence of metabolic cold adaptation. Polar Biol 14: 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Steffensen JF. (2002) Metabolic cold adaptation of polar fish based on measurements of aerobic oxygen consumption: fact or artefact? Artefact! Comp Biochem Physiol A 132: 789–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunday JM, Bates AE, Dulvy NK (2011) Global analysis of thermal tolerance and latitude in ectotherms. Proc Roy Soc B-Biol Sci 278: 1823–1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svendsen MBS, Bushnell P, Steffensen JF (2016) Design and setup of intermittent-flow respirometry system for aquatic organisms. J Fish Biol 88: 26–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verde C, Giordano D, Prisco G (2008) The adaptation of polar fishes to climatic changes: structure, function and phylogeny of haemoglobin. IUBMB Life 60: 29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhille CE, English KK, Cocherell DE, Farrell AP, Fangue NA (2016) High thermal tolerance of a rainbow trout population near its southern range limit suggests local thermal adjustment. Conserv Physiol 4: cow057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White CR, Alton LA, Frappell PB (2012) Metabolic cold adaptation in fishes occurs at the level of whole animal, mitochondria and enzyme. Proc Biol Sci 279: 1740–1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlschlag DE. (1960) Metabolism of an Antarctic fish and the phenomenon of cold adaptation. Ecology 41: 287–292. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Flato G., Kirchmeier-Young M., Vincent L., Wan H., Wang X., Rong R., Fyfe J., Li G. and Kharin V. V. (2019). Changes in temperature and precipitation across Canada. Canada’s Changing Climate Report, Government of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Chapter 4, pp. 112–193.

- Zhang Y, Claireaux G, Takle H, Jorgensen SM, Farrell AP (2018) A three-phase excess post-exercise oxygen consumption in Atlantic salmon Salmo salar and its response to exercise training. J Fish Biol 92: 1385–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Timmerhaus G, Anttila K, Mauduit F, Jørgensen SM, Kristensen T, Claireaux G, Takle H, Farrell AP (2016) Domestication compromises athleticism and respiratory plasticity in response to aerobic exercise training in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Aquaculture 463: 79–88. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.