Abstract

Background

Throughout China, during the recent epidemic in Hubei province, frontline medical staff have been responsible for tracing contacts of patients infected with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). This study aimed to investigate the psychological impact and coping strategies of frontline medical staff in Hunan province, adjacent to Hubei province, during the COVID-19 outbreak between January and March 2020.

Material/Methods

A cross-sectional observational study included doctors, nurses, and other hospital staff throughout Hunan province between January and March 2020. The study questionnaire included five sections and 67 questions (scores, 0–3). The chi-squared χ2 test was used to compare the responses between professional groups, age-groups, and gender.

Results

Study questionnaires were completed by 534 frontline medical staff. The responses showed that they believed they had a social and professional obligation to continue working long hours. Medical staff were anxious regarding their safety and the safety of their families and reported psychological effects from reports of mortality from COVID-19 infection. The availability of strict infection control guidelines, specialized equipment, recognition of their efforts by hospital management and the government, and reduction in reported cases of COVID-19 provided psychological benefit.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 outbreak in Hubei resulted in increased stress for medical staff in adjacent Hunan province. Continued acknowledgment of the medical staff by hospital management and the government, provision of infection control guidelines, specialized equipment and facilities for the management of COVID-19 infection should be recognized as factors that may encourage medical staff to work during future epidemics.

MeSH Keywords: Coronavirus Infections; Emotions; Medical Staff; Stress, Psychological; COVID-19

Background

Since the beginning of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak began in Hubei province from November 2019, frontline medical staff throughout China have experienced an increase in workload, increased working hours, and increased psychological stress. According to previous studies, during the outbreaks of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), frontline medical staff had reported high levels of stress that resulted in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [1,2]. The risk factors of psychological stress in medical staff had been previously investigated during the SARS and MERS epidemics. In 2008, Styra et al., in Toronto, identified four major risk factors for stress in medical staff during the SARS outbreak, including the perception of the medical of their risk of infection, the impact of SARS on their work, feelings of depression, and working in high-risk medical units [3]. The perception of infection risk by medical staff was previously reported by Tam et al. in 2003 to be significantly associated with their risk of developing PTSD [1]. Other factors, including social stigmatization and contact with infected patients, has previously been shown to be associated with increased levels of stress and anxiety in medical staff [2].

Although recent reports have shown that 80% of patients with COVID-19 have mild symptoms and will recover and the mortality rate is low at up to 2%, because of the high transmission rate, total mortality from COVID-19 is greater than SARS and MRES combined [4]. Recently, Peeri et al. reported that the infection rate of medical staff during the SARS and MERS outbreaks reached 21% and 18.6%, respectively, which resulted in adverse psychological effects, including anxiety and depression [5]. Medical staff have been infected and have died during the COVID-19 epidemic in China, there are no treatments for this infection, and no vaccines have been developed [6]. All these factors contribute to increased psychological stress of frontline medical staff in China, which may have immediate or long-psychological consequences that may have acute or chronic somatic effects that result in conditions such as cardiac arrhythmia and myocardial infarction [7]. However, there have been few studies that have investigated the coping strategies that frontline medical staff can use during disease epidemics. Personality traits, such as optimism, resilience, and altruism, have previously been shown to have positive effects on reducing psychological stress [6,8]. Objective measures may reduce psychological stress, including effective infection control, personal protective measures, clear institutional policies and protocols, which may help to reduce stress in medical staff [9]. Recognition and appreciation of the work and efforts by the medical profession, hospital management, government, and society have a positive impact on stress experienced by medical staff during epidemics [10]. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the psychological impact and coping strategies of frontline medical staff in Hunan province, adjacent to Hubei province, during the COVID-19 outbreak between January and March 2020.

Material and Methods

Ethical approval

A cross-sectional observational study included doctors, nurses, and other hospital staff throughout Hunan province between January and March 2020. The Institutional Review Board of the 3rd Xiangya Hospital of Central South University provided ethical approval for this study.

Study participants

Questionnaires were sent to frontline medical staff who were working during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The participants included doctors and nurses from departments of infectious diseases, emergency medicine, fever clinics, and intensive care units, and included technicians from radiology and laboratory medicine, and hospital staff from the section of infection prevention. A questionnaire was used that was previously designed by Lee et al. [11], which was used to evaluate medical staff during the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic. The questionnaire was modified for this study and included five sections with 67 questions. All participants were required to understand the meaning of the question and to answer the questions on their own.

Study questionnaire

The first section of the questionnaire included 14 questions that examined the feelings of the medical staff during the COVID-19 outbreak. Each question had four choices on a four-point scale (0=not at all; 1=slightly; 2=moderately; 3=very much). The second section investigated 19 possible factors that could induce stress for the medical staff (0=not at all; 1=slightly; 2=moderately; 3=very much). The third section included 14 questions to identify factors that might reduce their stress (0=never; 1=sometimes; 2=often; 3=always). The fourth section included 11 questions, which aimed to identify personal coping strategies in response to the stress of the outbreak, with four choices with responses that ranged from not important to most important (scores, 0–3). The fifth section included questions on what would encourage medical staff to be more confident in future outbreaks and included nine questions, consisting of four choices with responses that ranged from not important to most important (scores, 0–3).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was performed with GraphPad Prism version 7.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). The chi-squared χ2 test was used to compare the responses between professional groups, age-groups, and gender for the first four sections of the questionnaire. Descriptive statistics were used to present the data collected from the survey and included the mean, standard deviation (SD), and median of the data collected for all the sections. A P-value<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the study participants

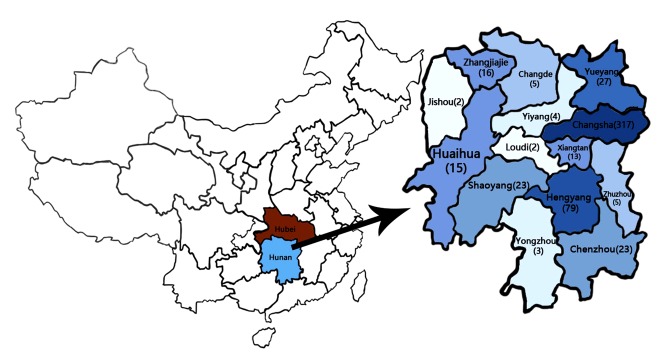

A total of 534 questionnaires were completed from 167 men and 367 women. The majority of participants were between the ages of 18–30 years (42.4%) and 31–40 years (60.7%). All the participants were working in hospitals in Hunan province. Doctors and nurses together accounted for 90% of the total participants. Most of the study participants were married (79%) and had children (76.6%). The average clinical experience was 14.5 years. Medical staff with a postgraduate degree represented the majority of the study participants (64.4%). The demographic characteristics of the study participants was shown in Table 1. All of the study participants were Chinese citizens and worked in different levels of hospital in Hunan, an adjacent province to Hubei. The questionnaires were evenly distributed to all administrative districts in Hunan. The top three participating districts were Changsha, Hengyang, and Yueyang (Figure 1), which were adjacent to the Jing-Guang Line, the most important railway and highway combining Hunan and Hubei.

Table 1.

Medical staff demographics (n=534).

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 36.4 (16.18) |

|

| |

| Gender, N (%) | |

| Female | 367 (68.7) |

| Male | 167 (31.3) |

|

| |

| Professional, N (%) | |

| Nurse | 248 (46.4) |

| Doctor | 233 (43.6) |

| Medical Technician | 48 (9.0) |

| Hospital staff | 5 (1.0) |

|

| |

| Married, N (%) | 422 (79.0) |

|

| |

| Having children, N (%) | 409 (76.6) |

|

| |

| Education degree, N (%) | |

| Undergraduate | 344 (64.4) |

| Master | 96 (18.0) |

| Doctor | 56 (10.5) |

| Others | 38 (7.1) |

Figure 1.

The distribution of the study participants from Hunan province, China, during the epidemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) between January and March 2020. (1) Hunan province is located in the central southern area of China, adjacent to Hubei province. (2) There were 534 completed questionnaires that included medical staff from 13 administrative districts of Hunan province, including Changsha (317), Hengyang (79), Yueyang (27), Chenzhou (23), Shaoyang (23), Zhangjiajie (16), Huaihua (15), Xiangtan (13), Zhuzhou (5), Changde (5), Yongzhou (3), Loudi (2), and Jishou (2).

The emotions of the medical staff in Hunan during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in Hubei

The emotions of the medical staff from the different medical professionals are shown in Table 2. The chi-squared χ2 test showed that differences in responses from eight of the 14 questions were statistically significant. The most important element was their social and moral responsibility, which drove them to continue working during the outbreak (P=0.03), and doctors had the highest mean score (2.47±0.66). Medical staff also expected to receive recognition from hospital authorities (P<0.001), and nurses had more concerns regarding extra financial compensation during or after the outbreak when compared with other healthcare workers (P=0.002). However, nursing staff also felt more nervous and anxious when on the ward when compared with other groups (P=0.02). Doctors were more unhappy about working overtime during the COVID-19 outbreak than other healthcare workers (P=0.02). There was no significant difference between the medical professionals for regarding stopping work, and work overload.

Table 2.

Staff feeling during COVID-19 outbreak among different position.

| Question | Condition | Groups | χ2 | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurses N=248 |

Doctors N=233 |

Medical Technician N=48 |

Hospital staff N=5 |

Total N=534 |

||||

| 1. You think that your current front-line job comes from your social and moral responsibility | Not at all | 13 (5.2) | 3 (1.3) | 2 (4.2) | 0 (0) | 18 (3.4) | 13.59 | 0.03* |

| Slight | 11 (4.4) | 13 (5.6) | 5 (10.4) | 0 (0) | 29 (5.4) | |||

| Moderate | 114 (50.0) | 89 (38.2) | 16 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 219 (41.0) | |||

| Very Much | 110 (44.4) | 128 (54.9) | 25 (52.1) | 5 (100) | 268 (50.2) | |||

| Mean±SD | 2.29±0.78 | 2.47±0.66 | 2.33±0.83 | 3.00±0.00 | 2.38±0.74 | |||

| 2. You have felt nervous or frighten in the ward | Not at all | 40 (16.2) | 46 (19.7) | 10 (20.8) | 2 (40) | 98 (18.4) | 15.02 | 0.02* |

| Slight | 88 (35.5) | 108 (46.4) | 22 (45.8) | 1 (20) | 219 (41.0) | |||

| Moderate | 96 (38.7) | 71 (30.5) | 13 (27.1) | 1 (20) | 181 (33.9) | |||

| Very Much | 24 (10.0) | 8 (3.4) | 3 (6.3) | 1 (20) | 36 (6.7) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.42±0.87 | 1.18±0.78 | 1.19±0.84 | 1.20±1.30 | 1.29±0.84 | |||

| 3. You were unhappy about working overtime during the outbreak. | Not at all | 133 (53.6) | 96 (41.2) | 31 (64.6) | 2 (40) | 262 (49.1) | 15.08 | 0.02* |

| Slight | 66 (26.6) | 85 (36.5) | 12 (25) | 1 (20) | 164 (30.7) | |||

| Moderate | 43 (17.4) | 42 (18.0) | 5 (10.4) | 1 (20) | 91 (17.0) | |||

| Very Much | 6 (2.4) | 10 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 17 (3.2) | |||

| Mean±SD | 0.69±0.84 | 0.85±0.86 | 0.46±0.68 | 1.20±1.30 | 0.74±0.85 | |||

| 4. You expect recognition of your work from the hospital authorities | Not at all | 12 (4.8) | 2 (0.9) | 8 (16.7) | 0 (0) | 22 (4.1) | 98.12 | <0.001*** |

| Slight | 21 (8.5) | 33 (14.1) | 24 (50) | 1 (20) | 79 (14.8) | |||

| Moderate | 103 (41.5) | 105 (45.1) | 16 (33.3) | 2 (40) | 226 (42.3) | |||

| Very Much | 112 (45.2) | 93 (39.9) | 0 (0) | 2 (40) | 207 (38.8) | |||

| Mean±SD | 2.27±0.81 | 2.24±0.72 | 2.17±0.69 | 2.20±0.84 | 2.25±0.76 | |||

| 5. You expect to receive bonus compensation during or after the outbreak | Not at all | 22 (8.9) | 18 (7.7) | 8 (16.7) | 2 (40) | 50 (9.4) | 20.67 | 0.002** |

| Slight | 38 (15.3) | 66 (28.3) | 15 (31.3) | 0 (0) | 119 (22.3) | |||

| Moderate | 94 (37.9) | 84 (36.1) | 15 (31.3) | 0 (0) | 193 (36.1) | |||

| Very Much | 94 (37.9) | 65 (27.9) | 10 (20.7) | 3 (60) | 172 (32.2) | |||

| Mean±SD | 2.05±0.94 | 1.84±0.92 | 1.56±1.01 | 1.80±1.64 | 1.91±0.96 | |||

| 6. You try to reduce exposure to patients diagnosed with COVID-19 | Not at all | 66 (26.5) | 54 (23.2) | 9 (18.8) | 2 (40) | 131 (24.5) | 11.74 | 0.07 |

| Slight | 78 (31.5) | 77 (33.0) | 19 (39.6) | 0 (0) | 174 (32.6) | |||

| Moderate | 82 (33.1) | 72 (30.9) | 9 (18.8) | 2 (40) | 165 (30.9) | |||

| Very Much | 22 (8.9) | 30 (12.9) | 11 (22.8) | 1 (20) | 64 (20.0) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.24±0.95 | 1.33±0.97 | 1.46±1.05 | 1.40±1.34 | 1.30±0.97 | |||

| 7. You want to stop your present job | Not at all | 156 (62.9) | 142 (60.9) | 45 (93.8) | 4 (80) | 347 (65.0) | 20.83 | 0.02** |

| Slight | 53 (21.4) | 57 (24.5) | 2 (4.2) | 1 (20) | 113 (21.2) | |||

| Moderate | 23 (9.3) | 23 (9.9) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 47 (8.8) | |||

| Very Much | 16 (6.4) | 11 (4.7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 27 (5.0) | |||

| Mean±SD | 0.59±0.90 | 0.58±0.85 | 0.08±0.35 | 0.20±0.45 | 0.54±0.85 | |||

| 8. You think HCWs who have not been exposed to COVID-19 should reduce their contact with you | Not at all | 53 (21.4) | 40 (17.2) | 14 (29.2) | 2 (40) | 109 (20.4) | 90.4 | <0.001*** |

| Slight | 41 (16.5) | 45 (19.3) | 14 (29.2) | 0 (0) | 100 (18.7) | |||

| Moderate | 70 (28.2) | 89 (38.2) | 12 (25.0) | 2 (40) | 173 (32.4) | |||

| Very Much | 84 (33.9) | 59 (25.3) | 8 (16.6) | 1 (20) | 152 (28.5) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.75±1.14 | 1.72±1.03 | 1.29±1.07 | 1.40±1.34 | 1.69±1.09 | |||

| 9. You want to be able to work in a unit where you don’t have to deal with patients with COVID-19 | Not at all | 96 (38.7) | 79 (33.9) | 23 (47.9) | 1 (20) | 199 (37.2) | 10.79 | 0.09 |

| Slight | 60 (24.2) | 69 (29.6) | 15 (31.3) | 2 (40) | 146 (27.3) | |||

| Moderate | 59 (23.8) | 47 (20.2) | 9 (18.7) | 0 (0) | 115 (21.5) | |||

| Very Much | 33 (13.3) | 38 (16.3) | 1 (2.1) | 2 (40) | 74 (14.0) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.12±1.07 | 1.19±1.08 | 0.75±0.84 | 1.60±1.34 | 1.12±1.06 | |||

| 10. You notice that other HCWs outside your department are avoiding contact with infected patients | Not at all | 47 (19.0) | 27 (11.6) | 12 (25.0) | 3 (60) | 89 (16.7) | 22.17 | 0.01** |

| Slight | 47 (19.0) | 47 (20.2) | 17 (35.4) | 1 (20) | 112 (21.0) | |||

| Moderate | 78 (31.5) | 83 (35.6) | 16 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 177 (33.1) | |||

| Very Much | 76 (30.5) | 76 (32.6) | 3 (6.3) | 1 (20) | 156 (29.2) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.74±1.09 | 1.89±0.99 | 1.21±0.90 | 0.80±1.30 | 1.75±1.05 | |||

| 11. If the epidemic suddenly gets worse, you will have to stop your job | Not at all | 166 (66.9) | 142 (610) | 41 (85.4) | 3 (60) | 352 (65.9) | 11.22 | 0.08 |

| Slight | 49 (20.0) | 56 (24.0) | 3 (6.3) | 2 (40) | 110 (20.6) | |||

| Moderate | 25 (10.1) | 27 (11.6) | 3 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 55 (10.3) | |||

| Very Much | 8 (3.0) | 8 (3.4) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 17 (3.2) | |||

| Mean±SD | 0.50±0.80 | 0.58±0.83 | 0.25±0.67 | 0.40±0.55 | 0.51±0.81 | |||

| 12. You feel angry because your workload is greater and more dangerous than other doctors who have not been exposed to COVID-19 | Not at all | 134 (54.0) | 124 (53.0) | 29 (60.4) | 3 (60) | 290 (54.3) | 8.303 | 0.22 |

| Slight | 53 (21.4) | 61 (26.0) | 15 (31.3) | 2 (40) | 131 (24.5) | |||

| Moderate | 44 (17.7) | 34 (15.0) | 4 (8.3) | 0 (0) | 82 (15.4) | |||

| Very Much | 17 (6.9) | 14 (6.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 31 (5.8) | |||

| Mean±SD | 0.77±0.97 | 0.73±0.92 | 0.48±0.65 | 0.40±0.55 | 0.73±0.93 | |||

| 13. You want to call in sick | Not at all | 207 (82.5) | 195 (83.7) | 46 (95.8) | 5 (100) | 453 (84.8) | 9.17 | 0.16 |

| Slight | 22 (8.9) | 28 (12.0) | 2 (40) | 0 (0) | 52 (9.7) | |||

| Moderate | 16 (6.5) | 8 (3.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 24 (4.5) | |||

| Very Much | 3 (12.1) | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (0.9) | |||

| Mean±SD | 0.25±0.63 | 0.21±0.54 | 0.04±0.20 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.22±0.56 | |||

| 14. You’ve been off work at least once | Not at all | 228 (92.0) | 219 (94.0) | 48 (100) | 5 (100) | 500 (93.6) | 8.555 | 0.2 |

| Slight | 10 (4.0) | 10 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 20 (3.7) | |||

| Moderate | 10 (4.0) | 3 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 13 (2.4) | |||

| Very Much | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | |||

| Mean±SD | 0.12±0.43 | 0.08±0.36 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.09±0.38 | |||

<0.05;

<0.01;

<0.001.

χ2 test was only performed among the groups of nurse, doctor and medical technician because of pretty small sample size in the group of hospital staff.

Factors that caused stress, according to the age of the medical staff

The study population was divided into four age-groups (Table 3). The main factors associated with stress were concerns for personal safety (P<0.001), concerns for their families (P<0.001), and concerns for patient mortality (P=0.001). Medical staff in the 31–40 year age-group were more worried about infecting their families compared with other groups (2.46±0.72). Staff>50 years of age felt greater stress when seeing their patients die. Worry about their own safety were also an important factor in anxiety in medical staff, particularly in the group aged 41–50 years. Lack of protective clothing (P=0.0195) and exhaustion due to increased duration of working (P=0.03) were also significantly increased in older staff. Stress from other colleagues affected staff >50 years old when compared with other groups (P=0.0034). The safety of their colleagues and the lack of treatment for COVID-19 were considered to be important factors that inducd stress in all medical staff, with no significant differences between the study groups.

Table 3.

Factors that caused stress among staff with different ages.

| Question | Condition | Groups (years old) | Total N=534 |

χ2 | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–30 N=150 |

31–40 N=215 |

41–50 N=117 |

50+ N=52 |

|||||

| 1. See your colleagues were infected | Not at all | 23 (15.3) | 24 (11.2) | 16 (13.7) | 9 (17.3) | 72 (13.5) | 8.109 | 0.52 |

| Slight | 26 (17.3) | 33 (15.3) | 20 (17.1) | 9 (17.3) | 88 (16.5) | |||

| Moderate | 45 (30.0) | 75 (34.9) | 31 (26.5) | 21 (40.4) | 172 (32.2) | |||

| Very Much | 56 (37.4) | 83 (38.6) | 50 (42.7) | 13 (25.0) | 202 (37.8) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.89±1.08 | 2.01±1.00 | 1.98±1.07 | 1.73±1.03 | 1.94±1.04 | |||

| 2. You’re worried about infecting your family | Not at all | 8 (5.33) | 3 (1.4) | 2 (1.7) | 3 (5.8) | 16 (3.0) | 137 | <0.001*** |

| Slight | 19 (12.7) | 20 (9.3) | 24 (20.5) | 5 (9.6) | 68 (12.7) | |||

| Moderate | 47 (31.3) | 68 (31.6) | 28 (24.0) | 20 (38.5) | 163 (30.6) | |||

| Very Much | 76 (50.7) | 124 (57.7) | 64 (53.8) | 24 (46.1) | 287 (53.7) | |||

| Mean±SD | 2.27±0.88 | 2.46±0.72 | 2.30±0.85 | 2.25±0.86 | 2.35±0.81 | |||

| 3. Small mistakes or inattentions can make you or others infected | Not at all | 6 (4.0) | 8 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (13.5) | 21 (3.9) | 37.69 | <0.001*** |

| Slight | 37 (25.0) | 41 (19.1) | 25 (21.4) | 3 (5.8) | 106 (19.9) | |||

| Moderate | 56 (37.0) | 93 (43.3) | 34 (29.1) | 25 (48.0) | 208 (39.0) | |||

| Very Much | 41 (34.0) | 73 (34.0) | 58 (49.5) | 17 (32.7) | 199 (37.2) | |||

| Mean±SD | 2.01±0.87 | 2.07±0.82 | 2.28±0.80 | 2.00±0.97 | 2.10±0.85 | |||

| 4. Take care of your infected colleagues | Not at all | 35 (23.3) | 44 (20.5) | 17 (14.5) | 9 (17.3) | 105 (19.7) | 12.88 | 0.17 |

| Slight | 37 (24.7) | 42 (19.5) | 33 (28.2) | 11 (21.1) | 123 (23.0) | |||

| Moderate | 50 (33.3) | 83 (38.6) | 32 (27.4) | 21 (40.4) | 186 (34.8) | |||

| Very Much | 28 (18.7) | 46 (21.4) | 35 (29.9) | 11 (21.2) | 120 (22.5) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.47±1.05 | 1.61±1.04 | 1.73±1.05 | 1.65±1.01 | 1.60±1.04 | |||

| 5. See your infected patient die in front of you | Not at all | 16 (10.7) | 25 (11.6) | 9 (7.7) | 2 (3.9) | 52 (9.7) | 27.06 | 0.001** |

| Slight | 19 (12.7) | 30 (14.0) | 35 (29.9) | 6 (11.5) | 70 (13.1) | |||

| Moderate | 57 (38.0) | 64 (29.8) | 40 (34.1) | 18 (34.6) | 168 (31.5) | |||

| Very Much | 58 (38.6) | 96 (44.7) | 33 (28.3) | 26 (50.0) | 244 (45.7) | |||

| Mean±SD | 2.05±0.97 | 2.07±1.02 | 2.26±0.96 | 2.31±0.83 | 2.13±0.98 | |||

| 6. You don’t know when the outbreak will be contained | Not at all | 7 (4.6) | 6 (2.8) | 9 (7.7) | 2 (3.9) | 24 (4.5) | 11.41 | 0.25 |

| Slight | 39 (26.0) | 69 (32.1) | 35 (29.9) | 18 (34.6) | 161 (30.1) | |||

| Moderate | 73 (48.7) | 94 (43.7) | 40 (34.2) | 19 (36.5) | 226 (42.3) | |||

| Very Much | 31 (20.7) | 46 (21.4) | 33 (28.2) | 13 (25.0) | 123 (23.1) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.85±0.80 | 1.84±0.79 | 1.83±0.93 | 1.83±0.86 | 1.84±0.83 | |||

| 7. New infections or suspected cases ask for your help. | Not at all | 12 (8.0) | 17 (7.9) | 15 (12.8) | 4 (7.7) | 48 (9.0) | 8.36 | 0.5 |

| Slight | 45 (30.0) | 73 (34.0) | 40 (34.2) | 20 (38.5) | 178 (33.3) | |||

| Moderate | 61 (40.7) | 89 (41.4) | 35 (29.9) | 19 (36.5) | 204 (38.2) | |||

| Very Much | 32 (21.3) | 36 (16.7) | 27 (23.1) | 9 (17.3) | 104 (19.5) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.75±0.88 | 1.67±0.85 | 1.63±0.98 | 1.63±0.86 | 1.68±0.89 | |||

| 8. Lack of specific treatment for COVID-19 | Not at all | 11 (7.3) | 11 (5.1) | 8 (6.8) | 3 (5.8) | 33 (6.2) | 6.732 | 0.67 |

| Slight | 46 (30.7) | 56 (26.0) | 29 (24.8) | 14 (26.9) | 145 (27.2) | |||

| Moderate | 61 (40.7) | 94 (43.7) | 42 (35.9) | 20 (38.5) | 217 (40.6) | |||

| Very Much | 32 (21.3) | 54 (25.1) | 38 (32.5) | 15 (28.8) | 139 (26.0) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.76±0.87 | 1.89±0.84 | 1.94±0.92 | 1.90±0.89 | 1.87±0.87 | |||

| 9. News, Weibo, WeChat, etc. report the number of new cases every day | Not at all | 9 (6.1) | 10 (4.7) | 7 (6.0) | 6 (11.5) | 32 (6.0) | 9.149 | 0.42 |

| Slight | 59 (39.3) | 80 (37.2) | 45 (38.5) | 15 (28.9) | 199 (37.3) | |||

| Moderate | 53 (35.3) | 96 (44.7) | 43 (36.8) | 22 (42.3) | 214 (40.0) | |||

| Very Much | 29 (19.3) | 29 (13.5) | 22 (18.7) | 9 (17.3) | 89 (16.7) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.68±0.85 | 1.67±0.77 | 1.68±0.85 | 1.65±0.90 | 1.67±0.82 | |||

| 10. You feel exhausted | Not at all | 43 (28.7) | 44 (20.5) | 26 (22.2) | 12 (23.1) | 125 (23.4) | 18.43 | 0.03* |

| Slight | 65 (43.3) | 97 (45.1) | 43 (36.8) | 31 (59.6) | 236 (44.2) | |||

| Moderate | 35 (23.3) | 57 (26.5) | 35 (29.9) | 4 (7.7) | 131 (24.5) | |||

| Very Much | 7 (4.7) | 17 (7.9) | 13 (11.1) | 5 (9.6) | 42 (7.9) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.04±0.85 | 1.22±0.86 | 1.30±0.94 | 1.04±0.84 | 1.17±0.88 | |||

| 11. When you see your colleagues showing symptoms of infection | Not at all | 17 (11.3) | 16 (7.4) | 8 (6.8) | 6 (11.5) | 47 (8.8) | 13.51 | 0.14 |

| Slight | 30 (20.0) | 46 (21.4) | 26 (22.2) | 3 (5.8) | 105 (19.7) | |||

| Moderate | 61 (40.7) | 77 (35.8) | 37 (31.6) | 23 (44.2) | 198 (37.0) | |||

| Very Much | 42 (28.0) | 76 (35.3) | 46 (39.4) | 20 (38.5) | 184 (34.5) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.85±0.96 | 1.99±0.93 | 2.03±0.95 | 2.10±0.96 | 1.97±0.95 | |||

| 12. When you have some respiratory symptoms, worry about whether you will be infected | Not at all | 7 (4.7) | 7 (3.3) | 7 (6.0) | 6 (11.5) | 27 (5.1) | 13.27 | 0.15 |

| Slight | 45 (30.0) | 50 (23.3) | 33 (28.2) | 13 (25.0) | 141 (26.4) | |||

| Moderate | 61 (40.7) | 107 (49.8) | 43 (36.8) | 24 (46.2) | 235 (44.0) | |||

| Very Much | 37 (24.6) | 51 (23.7) | 34 (29.0) | 9 (17.3) | 131 (24.5) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.85±0.85 | 1.94±0.77 | 1.89±0.90 | 1.69±0.90 | 1.88±0.84 | |||

| 13. You were infected by an infected patient while working at the hospital | Not at all | 24 (16.0) | 31 (14.4) | 18 (15.4) | 6 (11.5) | 79 (14.8) | 7.044 | 0.63 |

| Slight | 27 (18.0) | 34 (15.8) | 29 (24.8) | 11 (21.2) | 101 (18.9) | |||

| Moderate | 48 (32.0) | 74 (34.4) | 30 (25.6) | 20 (38.5) | 172 (32.2) | |||

| Very Much | 51 (34.0) | 76 (35.3) | 40 (34.2) | 15 (28.8) | 182 (34.1) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.84±1.07 | 1.91±1.04 | 1.79±1.08 | 1.85±0.98 | 1.86±1.05 | |||

| 14. You often feel weak and contradictory, between your own responsibility and life safety | Not at all | 33 (22.0) | 30 (14.0) | 24 (20.6) | 10 (19.2) | 97 (18.2) | 13.84 | 0.128 |

| Slight | 58 (38.7) | 86 (40.0) | 35 (29.9) | 12 (23.1) | 191 (35.8) | |||

| Moderate | 43 (28.6) | 75 (34.9) | 39 (33.3) | 20 (38.5) | 177 (33.1) | |||

| Very Much | 16 (10.7) | 24 (11.2) | 19 (16.2) | 10 (19.2) | 69 (12.9) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.28±0.93 | 1.43±0.87 | 1.45±1.00 | 1.58±1.02 | 1.41±0.93 | |||

| 15. Seeing stress or fear from your colleagues | Not at all | 41 (27.3) | 30 (14.0) | 10 (8.5) | 7 (13.5) | 88 (16.5) | 24.62 | 0.0034** |

| Slight | 54 (36.0) | 80 (37.2) | 55 (47.1) | 18 (34.6) | 207 (38.8) | |||

| Moderate | 45 (30.0) | 84 (39.1) | 39 (33.3) | 19 (36.5) | 187 (35.0) | |||

| Very Much | 10 (6.7) | 21 (9.8) | 13 (11.1) | 8 (15.4) | 52 (9.7) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.16±0.91 | 1.45±0.85 | 1.47±0.80 | 1.54±0.92 | 1.38±0.87 | |||

| 16. Constantly screen yourself for infection | Not at all | 41 (27.3) | 67 (31.2) | 43 (36.8) | 17 (32.7) | 167 (31.3) | 6.957 | 0.6416 |

| Slight | 61 (40.7) | 78 (36.3) | 34 (29.1) | 22 (42.3) | 195 (36.5) | |||

| Moderate | 35 (23.3) | 53 (24.7) | 33 (28.2) | 9 (17.3) | 130 (24.3) | |||

| Very Much | 13 (8.7) | 17 (7.9) | 8 (6.9) | 4 (7.7) | 42 (7.9) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.13±0.92 | 1.09±0.93 | 1.06±0.96 | 1.00±0.91 | 1.09±0.93 | |||

| 17. Every day for a long time stay in protective clothing | Not at all | 25 (16.7) | 23 (10.7) | 23 (19.7) | 10 (19.2) | 81 (15.2) | 19.76 | 0.0195* |

| Slight | 46 (30.7) | 77 (35.8) | 29 (24.8) | 14 (26.9) | 166 (31.1) | |||

| Moderate | 61 (40.6) | 85 (39.5) | 35 (29.9) | 20 (38.5) | 201 (37.6) | |||

| Very Much | 18 (12.0) | 30 (14.0) | 30 (25.6) | 8 (15.4) | 86 (16.1) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.48±0.91 | 1.57±0.86 | 1.62±1.07 | 1.50±0.98 | 1.55±0.94 | |||

| 18. You think the current protection measures are still lacking | Not at all | 24 (16.0) | 31 (14.4) | 28 (23.9) | 10 (19.2) | 96 (18.0) | 7.941 | 0.9401 |

| Slight | 64 (42.7) | 91 (42.3) | 41 (35.0) | 19 (36.5) | 215 (40.2) | |||

| Moderate | 46 (30.7) | 65 (30.2) | 36 (30.8) | 20 (38.5) | 167 (31.3) | |||

| Very Much | 16 (10.6) | 25 (11.6) | 12 (10.3) | 3 (5.8) | 56 (10.5) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.36±0.88 | 1.38±0.89 | 1.27±0.94 | 1.31±0.85 | 1.34±0.89 | |||

| 19. Often faced with a lack of more medical staff, medical equipment, medical resources | Not at all | 21 (14.0) | 20 (9.3) | 15 (12.8) | 5 (9.6) | 61 (11.4) | 3.773 | 0.9257 |

| Slight | 52 (34.7) | 75 (34.9) | 38 (32.5) | 17 (32.7) | 182 (34.1) | |||

| Moderate | 53 (35.3) | 76 (35.3) | 39 (33.3) | 20 (38.5) | 188 (35.2) | |||

| Very Much | 24 (16.0) | 44 (20.5) | 25 (21.4) | 10 (19.2) | 103 (19.3) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.53±0.92 | 1.67±0.91 | 1.63±0.96 | 1.67±0.90 | 1.62±0.92 | |||

<0.05;

<0.01;

<0.001.

Factors that helped to reduce stress of medical staff during the COVID-19 outbreak, according to gender

Section 3 of the study questionnaire aimed to identify could directly or indirectly help to reduce stress for a COVID-19 outbreak according to the previous severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreaks, and these were evaluated in Section 3 (Table 4). In this section, we would like to look for differences from the sexual perspective. The safety of family was the biggest impact in reducing staff stress (P=0.37>0.05), though there are no significant difference in different genders. However, factors like correct guidance and effective safeguards for prevention from disease transmission eased more female staff anxiety (P<0.001). The positive attitude from their colleagues was also important factor to reduce staff distress during the outbreak (P=0.04). In general, factors of reducing stress had larger impact on female staff than male ones.

Table 4.

Factors that helped in reducing stress during COVID-19 outbreak between genders.

| Question | Condition | Groups | Total N=534 | χ2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male N=167 | Female N=367 | |||||

| 1. Positive attitude from your colleagues | Never | 7 (4.2) | 9 (2.5) | 16 (3.0) | 8.586 | 0.04* |

| Sometimes | 54 (32.3) | 83 (22.6) | 137 (25.7) | |||

| Often | 77 (46.1) | 184 (50.1) | 261 (48.8) | |||

| Always | 29 (17.4) | 91 (24.8) | 120 (22.5) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.77±0.78 | 1.97±0.76 | 1.91±0.77 | |||

| 2. After effective protection measures have been taken, none of your colleagues have been infected with the virus | Never | 21 (12.6) | 26 (7.1) | 47 (8.8) | 20 | <0.001*** |

| Sometimes | 31 (18.6) | 37 (10.1) | 68 (12.7) | |||

| Often | 63 (37.7) | 122 (33.2) | 185 (34.7) | |||

| Always | 52 (31.1) | 182 (49.6) | 234 (43.8) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.87±1.00 | 2.25±0.90 | 2.13±0.95 | |||

| 3. Your patient is getting better | Never | 7 (4.2) | 9 (2.5) | 16 (3.0) | 9.167 | 0.03* |

| Sometimes | 27 (16.2) | 37 (10.0) | 64 (12.0) | |||

| Often | 80 (47.9) | 161 (43.9) | 241 (45.1) | |||

| Always | 53 (31.7) | 160 (43.6) | 213 (39.9) | |||

| Mean±SD | 2.07±0.80 | 2.29±0.74 | 2.22±0.77 | |||

| 4. Your infected colleague is getting better | Never | 23 (13.8) | 29 (7.9) | 52 (9.7) | 17.56 | <0.001*** |

| Sometimes | 26 (15.6) | 32 (8.7) | 58 (10.9) | |||

| Often | 72 (43.1) | 144 (39.2) | 216 (40.4) | |||

| Always | 46 (27.5) | 162 (44.2) | 208 (39.0) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.84±0.98 | 2.20±0.90 | 2.09±0.94 | |||

| 5. Your hospital provides you with effective safeguards | Never | 4 (2.4) | 3 (0.8) | 7 (1.3) | 5.117 | 0.16 |

| Sometimes | 26 (25.6) | 45 (12.3) | 71 (13.3) | |||

| Often | 74 (44.3) | 151 (41.1) | 225 (42.1) | |||

| Always | 63 (37.7) | 168 (45.8) | 231 (43.3) | |||

| Mean±SD | 2.17±0.78 | 2.32±0.72 | 2.27±0.74 | |||

| 6. Hospital’s correct guidance for infection prevention | Never | 4 (2.4) | 5 (1.4) | 9 (1.7) | 2.932 | 0.4 |

| Sometimes | 17 (10.2) | 33 (9.0) | 50 (9.4) | |||

| Often | 75 (44.9) | 146 (39.7) | 221 (41.3) | |||

| Always | 71 (42.5) | 183 (49.9) | 254 (47.6) | |||

| Mean±SD | 2.28±0.74 | 2.38±0.71 | 2.35±0.72 | |||

| 7. None of your family members are infected and are in a relatively safe state | Never | 8 (4.8) | 13 (3.5) | 21 (3.9) | 3.158 | 0.37 |

| Sometimes | 10 (6.0) | 16 (4.4) | 26 (4.9) | |||

| Often | 48 (28.7) | 91 (24.8) | 139 (26.0) | |||

| Always | 101 (60.5) | 247 (67.3) | 348 (65.2) | |||

| Mean±SD | 2.45±0.81 | 2.56±0.74 | 2.52±0.76 | |||

| 8. Decrease in reported cases | Never | 6 (3.6) | 7 (1.9) | 13 (2.4) | 6.195 | 0.1 |

| Sometimes | 25 (15.0) | 39 (10.6) | 64 (12.0) | |||

| Often | 71 (42.5) | 141 (38.4) | 212 (39.7) | |||

| Always | 65 (38.9) | 180 (49.1) | 245 (45.9) | |||

| Mean±SD | 2.17±0.81 | 2.35±0.74 | 2.29±0.77 | |||

| 9. You get extra financial compensation when you work in the field. | Never | 24 (14.4) | 43 (11.7) | 67 (12.5) | 1.568 | 0.67 |

| Sometimes | 76 (45.5) | 158 (43.1) | 234 (43.8) | |||

| Often | 39 (23.4) | 100 (27.2) | 139 (26.0) | |||

| Always | 28 (16.8) | 66 (18.0) | 94 (17.7) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.43±0.93 | 1.51±0.92 | 1.49±0.92 | |||

| 10. Your familiar friends, colleagues, leaders work with you in the field | Never | 6 (3.6) | 10 (2.7) | 16 (3.0) | 11.18 | 0.01* |

| Sometimes | 42 (25.1) | 59 (16.1) | 101 (18.9) | |||

| Often | 75 (44.9) | 153 (41.7) | 228 (42.7) | |||

| Always | 44 (26.3) | 145 (39.5) | 189 (35.4) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.94±0.81 | 2.18±0.80 | 2.10±0.81 | |||

| 11. Once you get infected, your trust in the hospital will give you peace of mind | Never | 14 (8.4) | 17 (4.6) | 31 (5.8) | 5.751 | 0.12 |

| Sometimes | 35 (21.0) | 93 (25.4) | 128 (24.0) | |||

| Often | 74 (44.3) | 141 (38.4) | 215 (40.2) | |||

| Always | 44 (26.3) | 116 (31.6) | 160 (30.0) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.89±0.89 | 1.98±0.87 | 1.95±0.88 | |||

| 12. Joking and chatting with your colleagues | Never | 6 (3.6) | 9 (2.5) | 15 (2.8) | 2.689 | 0.44 |

| Sometimes | 39 (23.4) | 75 (20.3) | 114 (21.3) | |||

| Often | 79 (47.3) | 165 (45.0) | 244 (45.8) | |||

| Always | 43 (25.7) | 118 (32.2) | 161 (30.1) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.95±0.80 | 2.07±0.79 | 2.03±0.79 | |||

| 13. No overtime | Never | 23 (13.8) | 28 (7.7) | 51 (9.5) | 8.537 | 0.04* |

| Sometimes | 72 (43.1) | 138 (37.6) | 210 (39.3) | |||

| Often | 45 (26.9) | 122 (33.2) | 167 (31.3) | |||

| Always | 27 (16.2) | 79 (21.5) | 106 (19.9) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.46±0.92 | 1.69±0.89 | 1.61±0.91 | |||

| 14. Received free lunch, milk tea prepared by the hospital for frontline staff | Never | 10 (6.0) | 18 (4.9) | 28 (5.2) | 8.726 | 0.03* |

| Sometimes | 51 (30.5) | 76 (20.7) | 127 (23.8) | |||

| Often | 61 (36.5) | 135 (36.8) | 196 (36.7) | |||

| Always | 45 (26.9) | 138 (37.6) | 183 (34.3) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.84±0.89 | 2.07±0.88 | 2.00±0.89 | |||

<0.05;

<0.01;

<0.001.

Personal coping strategies used by the medical staff to reduce stress among professionals

Section 4 of the study questionnaire was designed to provide insights into the personal coping strategies used by the different professional groups of the medical staff (Table 5). Strategies, such as strict protective measures, knowledge of virus prevention and transmission, social isolation measures, and positive self-attitude resulted in the highest scores (mean scores <2.5), with nurses giving the highest scores in every question. Seeking help from family and friends was a significant supportive measure (P<0.001). Medical staff did not express a significant wish to reduce stress by consulting a psychologist to discuss their emotions, especially in the populations of doctors and medical technicians.

Table 5.

Personal coping strategies used by the staff to alleviate stress among professionals.

| Question | Condition | Groups | Total N=534 |

χ2 | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurses N=248 |

Doctors N=233 |

Medical Technician N=48 |

Hospital staff N=5 |

|||||

| 1. Follow strict protective measures, such as hand washing, masks, face masks, protective clothing, etc. | Not at all important | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.86) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.6) | 9.025 | 0.17 |

| Slightly important | 3 (1.2) | 6 (2.58) | 2 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (2.1) | |||

| Important | 30 (12.1) | 45 (19.31) | 10 (20.8) | 0 (0.0) | 85 (15.9) | |||

| Very Important | 214 (86.3) | 180 (77.25) | 36 (75.0) | 5 (1.0) | 435 (81.4) | |||

| Mean±SD | 2.84±0.43 | 2.73±0.55 | 2.71±0.54 | 3.00±0.00 | 2.78±0.50 | |||

| 2. Every fever patient may be infected with COVID-19, even if the nucleic acid test is negative | Not at all important | 4 (1.6) | 3 (1.29) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (1.3) | 19.16 | 0.004** |

| Slightly important | 11 (4.4) | 30 (12.88) | 4 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) | 45 (8.4) | |||

| Important | 74 (29.8) | 89 (38.20) | 17 (35.4) | 2 (0.4) | 182 (34.1) | |||

| Very Important | 159 (64.1) | 111 (47.64) | 27 (56.3) | 3 (0.6) | 300 (56.2) | |||

| Mean±SD | 2.56±0.66 | 2.32±0.75 | 2.48±0.65 | 2.60±0.55 | 2.45±0.70 | |||

| 3. Learn about COVID-19, its prevention and mechanism of transmission | Not at all important | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 9.207 | 0.16 |

| Slightly important | 6 (2.4) | 5 (2.15) | 2 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (2.4) | |||

| Important | 46 (18.5) | 68 (29.18) | 12 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 126 (23.6) | |||

| Very Important | 195 (78.6) | 160 (68.67) | 34 (70.8) | 5 (1.0) | 394 (73.8) | |||

| Mean±SD | 2.75±0.51 | 2.67±0.52 | 2.67±0.56 | 3.00±0.00 | 2.71±0.52 | |||

| 4. Choose a more single mode of travel, such as self-driving, and avoid transportation such as subways | Not at all important | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.86) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.9) | 54.37 | <0.001*** |

| Slightly important | 4 (1.6) | 16 (6.87) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (3.9) | |||

| Important | 56 (22.6) | 65 (27.90) | 12 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 133 (24.9) | |||

| Very Important | 186 (75.0) | 150 (64.38) | 34 (70.8) | 5 (1.0) | 375 (70.3) | |||

| Mean±SD | 2.72±0.53 | 2.56±0.66 | 2.65±0.64 | 3.00±0.00 | 2.64±0.60 | |||

| 5. Do some leisure activities in your free time, such as watching movies, reading, etc. | Not at all important | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.43) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.6) | 13.68 | 0.03* |

| Slightly important | 18 (7.3) | 26 (11.16) | 5 (10.4) | 0 (0.0) | 49 (9.1) | |||

| Important | 78 (31.5) | 96 (41.20) | 24 (50.0) | 1 (0.2) | 199 (37.3) | |||

| Very Important | 150 (60.5) | 110 (47.21) | 19 (39.6) | 4 (0.8) | 283 (53.0) | |||

| Mean±SD | 2.52±0.67 | 2.35±0.69 | 2.29±0.65 | 2.80±0.45 | 2.43±0.68 | |||

| 6. Chatted with family and friends to relieve stress and obtain support | Not at all important | 2 (0.8) | 8 (3.43) | 3 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (2.4) | 29.42 | <0.001*** |

| Slightly important | 27 (10.9) | 54 (23.18) | 12 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 93 (17.4) | |||

| Important | 90 (36.3) | 93 (39.91) | 15 (31.3) | 1 (0.2) | 199 (37.3) | |||

| Very Important | 129 (52.0) | 78 (33.48) | 18 (37.5) | 4 (0.8) | 229 (42.9) | |||

| Mean±SD | 2.40±0.71 | 2.03±0.84 | 2.00±0.95 | 2.8±0.45 | 2.21±0.81 | |||

| 7. Talking to yourself and motivating to face the COVID-19 outbreak with positive attitude | Not at all important | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.86) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.6) | 10.23 | 0.12 |

| Slightly important | 15 (6.0) | 14 (6.01) | 6 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 35 (6.6) | |||

| Important | 74 (29.8) | 94 (40.34) | 14 (29.2) | 0 (0.0) | 182 (34.0) | |||

| Very Important | 158 (63.7) | 123 (52.79) | 28 (58.3) | 5 (1.0) | 314 (58.8) | |||

| Mean±SD | 2.57±0.63 | 2.45±0.65 | 2.46±0.71 | 3.00±0.00 | 2.51±0.64 | |||

| 8. Seek help from a psychologist | Not at all important | 26 (10.5) | 75 (32.19) | 17 (35.4) | 1 (0.2) | 119 (22.3) | 69.11 | <0.001*** |

| Slightly important | 64 (25.8) | 80 (34.33) | 19 (39.6) | 2 (0.4) | 165 (30.9) | |||

| Important | 78 (31.5) | 53 (22.75) | 6 (12.5) | 1 (0.2) | 138 (25.8) | |||

| Very Important | 80 (32.3) | 25 (10.73) | 6 (12.5) | 1 (0.2) | 112 (21.0) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.85±0.99 | 1.12±0.98 | 1.02±1.00 | 1.40±1.14 | 1.46±1.06 | |||

| 9. Avoided doing overtime to reduce exposure to COVID-19 patients in hospital | Not at all important | 33 (13.3) | 45 (19.31) | 12 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 90 (16.9) | 26.88 | <0.001*** |

| Slightly important | 65 (26.2) | 73 (31.33) | 21 (43.8) | 2 (0.4) | 161 (30.1) | |||

| Important | 79 (31.9) | 81 (34.76) | 12 (25.0) | 1 (0.2) | 173 (32.4) | |||

| Very Important | 71 (28.6) | 34 (14.59) | 3 (6.3) | 2 (0.4) | 110 (20.6) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.76±1.01 | 1.45±0.96 | 1.13±0.87 | 2.00±1.00 | 1.57±1.00 | |||

| 10. Avoided media news about COVID-19 and related fatalities | Not at all important | 80 (32.3) | 108 (46.35) | 26 (54.2) | 2 (0.4) | 216 (40.4) | 27.12 | <0.001*** |

| Slightly important | 61 (24.6) | 66 (28.33) | 15 (31.3) | 0 (0.0) | 142 (26.6) | |||

| Important | 68 (27.4) | 36 (15.45) | 6 (12.5) | 2 (0.4) | 112 (21.0) | |||

| Very Important | 39 (15.7) | 23 (9.87) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (0.2) | 64 (12.0) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.27±1.08 | 0.89±1.00 | 0.63±0.79 | 1.40±1.34 | 1.04±1.05 | |||

| 11. Vented emotions by crying, screaming etc. | Not at all important | 83 (33.5) | 135 (57.94) | 35 (72.9) | 2 (0.4) | 255 (47.8) | 45.82 | <0.001*** |

| Slightly important | 87 (35.1) | 56 (24.03) | 11 (22.9) | 1 (0.2) | 155 (29.0) | |||

| Important | 50 (20.2) | 29 (12.45) | 2 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | 81 (15.2) | |||

| Very Important | 28 (11.3) | 13 (5.58) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | 43 (8.1) | |||

| Mean±SD | 1.09±0.99 | 0.66±0.90 | 0.31±0.55 | 1.40±1.52 | 0.84±0.96 | |||

<0.05;

<0.01;

<0.001.

χ2 test was only performed among the groups of nurse, physician and medical technician because of pretty small sample size in the group of others.

Motivational factors to encourage continuation of work in future outbreaks of infection

Section 5 of the study questionnaire included questions for the medical staff about motivators to continue working during any future COVID-19 or other epidemic outbreaks (Table 6). Adequate protective equipment provided by the hospitals was considered to be the most important motivational factor to encourage continuation of work in future outbreaks. The availability of strict infection control guidelines, specialized equipment, recognition of their efforts by hospital management and the government, and reduction in reported cases of COVID-19 provided psychological benefit.

Table 6.

Motivational factors to encourage continuation of work in future outbreaks (N=534, Maximum score=3)

| Motivational factors for future outbreaks | Mean (SD) | Median | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Similar adequate personal protective equipment supply by the Hospital | 2.71 | 3 | 0.56 |

| 2. Treatments effective for diseases or application of vaccines | 2.66 | 3 | 0.59 |

| 3. Family support | 2.61 | 3 | 0.61 |

| 4. Social, media identity | 2.59 | 3 | 0.64 |

| 5. Compensation to family if disease related infection or death at work | 2.36 | 3 | 0.83 |

| 6. Reduce working hours and more flexible scheduling during epidemics | 2.29 | 2 | 0.81 |

| 7. The hospital’s financial support for you | 2.28 | 2 | 0.83 |

| 8. Hospital can provide psychologist support | 2.11 | 2 | 0.96 |

| 9. Reduce overtime | 2.05 | 2 | 0.93 |

Discussion

Frontline medical staff during epidemics of infectious disease include doctors and nurses from departments of infectious disease, emergency medicine, fever clinics, and intensive care units, and technicians mainly from radiology and laboratory medicine, and hospital staff from infection control [11]. Previous studies during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreaks have shown that medical staff are not only under stress during epidemics, but they may also suffer psychologically long after the initial outbreak is over [10,12]. Although each epidemic has significant differences due to geographic location, pathogen characteristics, route of transmission, infectivity, mortality rate, and availability of treatments, based on previous studies, epidemics have a significant impact on the psychological wellbeing of medical staff [13]. The present study was the first to investigate the psychological effects of the recent outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei, China, on the medical staff of Hunan province, from the aspects of emotions, perceived stressors, and coping strategies. This study also investigated motivational factors that might encourage the continuation of work in future similar outbreaks.

Dongting Lake separates the adjacent provinces of Hunan and Hubei, which have similar cultures and are linked by transportation, and there is frequent migration between these two provinces. Therefore, the development of an epidemic in Hubei province is likely to affect Hunan, and the degree of clinical work and psychological stress of medical staff in Hunan is second only to that of Hubei. An understanding of psychological effects, perceived stressors, and coping strategies from the Hunan medical staff is important and may have implications for medical staff in other Chinese provinces, and other countries.

The findings from the present study showed that frontline medical staff experienced emotional stress during the COVID-19 outbreak, which has been supported by previous studies on other epidemics, although their extent differs [9,10]. However, in the present study, expectations of financial compensation during or after the outbreak were not established, which differed from other studies [10,14]. However, medical staff in Hunan expected recognition from the health authorities, as reported during previous epidemics [9,10]. Also, the most important factors that motivated them to continue working were their social and moral responsibilities and professional obligations.

For medical staff in Hunan, safety from infection was the main concern as they worried most that they might infect their families with COVID-19. Medical staff between 31–40 years of age had the greatest concern regarding viral transmission to their families, possibly because most of them had young children and living parents in their families. These findings were also reported among medical staff during the SARS epidemic but were less significant [15]. Another cause of stress for the medical staff in this study was an awareness of the mortality rate from COVID-19 infection. All age groups in this study expressed psychological stress when they saw their colleagues under stress. Therefore, hospital managers and governments should improve interventions for preventing the spread of epidemics, promote disease treatment methods, and also offer psychological support for medical staff. In the present study, the study participants showed less concern regarding the new cases and lack of treatment for COVID-19, which was not consistent with previous studies during other infectious disease epidemics [10]. Medical staff were satisfied with current protection measures, the numbers of medical staff, medical equipment, and medical resources, although these were identified as problems by the general public and the media [8]. This finding might be explained because, at the time of this study, the COVID-19 epidemic in Hunan was not as severe as that in Wuhan and Hubei, and disease prevention measures in Hunan were being instigated, and medical workers and the general population were better informed about these measures [16].

Previous studies have shown that gender differences exist regarding the ability to cope with stress [17,18]. Women in society and at work are more likely than men to develop social and personal mechanisms to cope with stress [17,18]. The responses to the questionnaires in the present study showed that the most important factor that helped ease the stress of the medical staff was when their family was well, not infected with COVID-19, and were not believed to be at risk of infection. A positive working environment with the re-assurance of personal safety while at work during the COVID-19 epidemic were the two main factors that might be key to encourage medical staff to continue working during the epidemic. Also, awareness of the effects of disease prevention measures with reduced numbers of reported cases reduced staff stress. Financial or other forms of remuneration were not significant concerns by medical staff in this study. The personal coping strategies that were used by medical staff to reduce stress during the COVID-19 epidemic is an important topic to investigate that requires further long-term studies as in China and throughout the world. During this study, medical staff in Hunan who were under stress from the COVID-19 epidemic were reassured by the implementation of clear disease prevention guidelines, including handwashing, the use of face masks, and protective clothing [19].

Recently, Cheng et al. commented that with the development of the COVID-19 epidemic, infection control was important as there is still no vaccine or antiviral therapy, but that testing based on the identification of viral RNA using polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based tests may show false-negatives [20]. Li et al. have recently reported that both anti-virus IgM and IgG could be used for confirmed diagnosis when molecular testing is negative [21]. Screening of all individuals with a fever is recommended, and awareness of aerosol and droplet spread of COVID-19 has supported avoiding social gatherings and public transport. During infectious disease epidemics, support from family and friends, as well as a positive attitude, have previously been shown to reduce stress [22]. However, in China, medical staff are less likely to seek help from a psychologist or to express their emotions, when compared with medical staff in western countries.

There have been recent epidemics with novel forms of coronavirus that have included the SARS outbreak in 2003, and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreak in 2014, which are now followed by the COVID-19 outbreak from 2019. In 2005, Wang et al. reported the findings from a study on the psychological impact of the SARS outbreak on emergency healthcare workers [23]. The findings showed that psychological stress was greatest for emergency nurses, followed by emergency doctors, and then for healthcare assistants [23]. This previous study showed that the most important variables associated with stress included loss of control and vulnerability to infection, the fear for personal health, and the spread of the novel virus [23]. The most common coping strategies by emergency medical staff were previously reported to include acceptance of the medical situation, the active use of coping strategies, and positive framing or outlook while working [23].

This study had several limitations. The study was designed as a cross-sectional observational study that included doctors, nurses, and other hospital staff throughout Hunan province and was of short duration, conducted between January and March 2020. However, psychological stress can accumulate over time and have an impact later in the outbreak, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which should be investigated in future studies. Also, although the staff included in this study were all from frontline medical departments that included departments of infectious diseases, emergency medicine, fever clinics, intensive care units, radiology, and laboratory medicine, this study did not analyze the differences between workers in different departments. Following the findings from this preliminary observational study, the risk factors associated with the psychological impact of the COVID-19 infection should be investigated in future long-term studies. Because this was a cross-sectional study, the effects of continuous changes on the psychological status of medical workers were not studied. Finally, the data from this study was based on subjective responses using questionnaires, and in future studies, these findings should be supported by objective measurements of stress.

Conclusions

This study aimed to investigate the psychological impact and coping strategies of frontline medical staff in Hunan province, adjacent to Hubei province, during the COVID-19 outbreak between January and March 2020. The findings showed that the COVID-19 epidemic in Hubei resulted in increased workload and stress for medical staff in the adjacent province of Hunan. The main factors associated with stress included the perceived risk of infection to themselves and their families, patient mortality, the availability of clear infection control guidance, the availability of effective protective equipment, recognition of their work by hospital authorities, and a decrease in reported cases of COVID-19. Staff support and the provision of facilities and equipment by hospital managers and the government are required to retain and encourage medical staff involvement in future epidemics.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

Source of support: Grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81700658 and 81974079), the National Science and Technology Major Project (No. 2017ZX10202203), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (No. 2016JJ4105), and the New Xiangya Talent Project of the Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (No. JY201629)

References

- 1.Tam CWC, Pang EPF, Lam LCW, Chiu HFK. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Hong Kong in, 2003: Stress and psychological impact among frontline healthcare workers. Psychol Med. 2004;34(7):1197–204. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704002247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee SM, Kang WS, Cho A, et al. Psychological impact of the, 2015 MERS outbreak on hospital workers and quarantined hemodialysis patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2018;87:123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Styra R, Hawryluck L, Robinson S, et al. Impact on health care workers employed in high-risk areas during the Toronto SARS outbreak. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64(2):177–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahase E. Coronavirus covid-19 has killed more people than SARS and MERS combined, despite lower case fatality rate. BMJ. 2020;368:m641. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peeri NC, Shrestha N, Rahman MS, et al. The SARS, MERS and novel coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemics, the newest and biggest global health threats: What lessons have we learned? Int J Epidemiol. 2020 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa033. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z, et al. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: Exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54(5):302–11. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esler M. Mental stress and human cardiovascular disease. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;74(Pt B):269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park J-S, Lee E-H, Park N-R, Choi YH. Mental Health of Nurses Working at a Government-designated Hospital During a MERS-CoV Outbreak: A Cross-sectional Study. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2018;32(1):2–6. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koh D, Lim MK, Chia SE, et al. Risk perception and impact of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) on work and personal lives of healthcare workers in Singapore: what can we learn? Med Care. 2005;43(7):676–82. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000167181.36730.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khalid I, Khalid TJ, Qabajah MR, et al. Healthcare workers emotions, perceived stressors and coping strategies during a MERS-CoV outbreak. Clin Med Res. 2016;14(1):7–14. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2016.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee SH, Juang YY, Su YJ, et al. Facing SARS: psychological impacts on SARS team nurses and psychiatric services in a Taiwan general hospital. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27(5):352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gee S, Skovdal M. The role of risk perception in willingness to respond to the, 2014–2016 West African Ebola outbreak: A qualitative study of international health care workers. Glob Health Res Policy. 2017;2:21. doi: 10.1186/s41256-017-0042-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin CY, Peng YC, Wu YH, et al. The psychological effect of severe acute respiratory syndrome on emergency department staff. Emerg Med J. 2007;24(1):12–17. doi: 10.1136/emj.2006.035089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koh Y, Hegney DG, Drury V. Comprehensive systematic review of healthcare workers’ perceptions of risk and use of coping strategies towards emerging respiratory infectious diseases. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2011;9(4):403–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-1609.2011.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ly T, Selgelid MJ, Kerridge I. Pandemic and public health controls: Toward an equitable compensation system. J Law Med. 2007;15(2):296–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Balderson KE, et al. Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(12):1924–1932. doi: 10.3201/eid1212.060584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunan Provincial Center For Disease Control and Prevention Emergency Office Director. Timely Response To The Outbreak Changes, To Prevent The Outbreak Rebound. Mar, 2020. Avalable at [URL]: http://hunan.voc.com.cn/article/202003/202003061951235674.html.

- 18.Eisenbarth CA. Coping with stress: Gender differences among college students. College Student Journal. 2019;53(2):151–162. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen-Louck K, Levy I. Risk perception of a chronic threat of terrorism: Differences based on coping types, gender and exposure. Int J Psychol. 2020;55(1):115–22. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng VCC, Wong SC, To KKW, et al. Preparedness and proactive infection control measures against the emerging novel coronavirus in China. J Hosp Infect. 2020;104(3):254–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Z, Yi Y, Luo X, et al. Development and Clinical Application of A Rapid IgM-IgG Combined Antibody Test for SARS-CoV-2 Infection Diagnosis. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25727. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lai THT, Tang EWH, Chau SKY, et al. Stepping up infection control measures in ophthalmology during the novel coronavirus outbreak: An experience from Hong Kong. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00417-020-04641-8. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong TW, Yau JKY, Chan CLW, et al. The psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak on healthcare workers in emergency departments and how they cope. Eur J Emerg Med. 2005;12(1):13–18. doi: 10.1097/00063110-200502000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.16 Cases a Day! China’s Epidemic Prevention and Control Faces New Challenges as Overseas Imports Increase. Available at [URL]: http://news.sina.com.cn/o/2020-03-06/doc-iimxxstf6983661.shtml.