To the Editor,

the current outbreak of COVID-19 in Lombardy, a region of Northern Italy, has dramatically impacted the organization of healthcare activities. As the infection escalates, in the hopes of conserving resources, a number of hospitals reduced elective surgeries as part of their COVID-19 containment strategy.

Patients requiring oncologic resection were offered the possibility to be referred to the two COVID-19-free regional oncologic hubs, both located in Milan.

In our Institution, all available beds in intensive care units (ICU) were instantaneously saturated by COVID-19 patients [1] despite the fact that the overall ICU recovery capacity for adults increased from 29 to 57 beds. Surgery at our Head and Neck Department in Brescia was reduced from 3 operating theatres running 5 days per week, to 1 theater running 2 days per week.

For those refusing to be referred to the aforementioned structures, relevant adjustments in global management were mandatory. To cope with the very limited availability of anesthesiologists, and to avoid waste of precious resources, the surgical strategy was re-discussed in order to reduce operating times, possibly minimizing the risk of complications and postoperative ICU admission.

The aim of the demolition phase is radicality, and thus cancer resection remains standard. Conversely, the reconstructive phase can be tailored to better cope with current constraints.

In the first two weeks of March 2020, during the striking phase of the Italian COVID-19 emergency, 3 patients affected by HN-SCC underwent surgery at the Otolaryngology Unit of the University of Brescia, Italy.

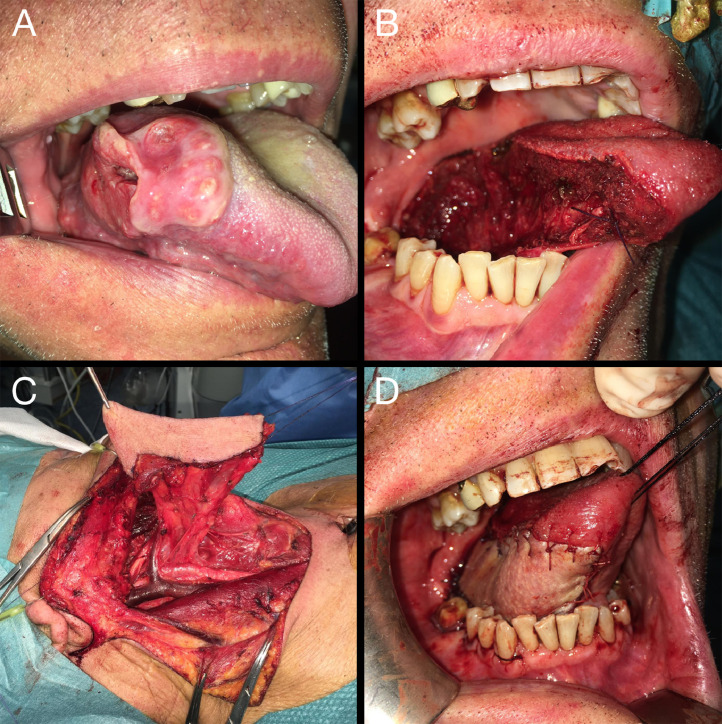

Patient 1, presenting a tongue cT3N0 SCC, underwent pull through resection with en-bloc selective neck dissection I-III and temporary tracheostomy. Initially scheduled for a radial forearm free flap (FF), he underwent infrahyoid pedicled flap (PF) reconstruction (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Clinical case of a right cT3N0-pT3N2b squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue (A). The patient underwent pull through tumor resection (B) with en bloc selective neck dissection I-III plus temporary tracheostomy. An infrahyoid PF was harvested (C) and transposed to cover the oral cavity defect (D). Operative time was 3 h and 35 min.

Patient 2, presenting a cT4aN0 inferior alveolar ridge tumor, underwent lateral segmental mandibular resection with en-bloc selective neck dissection I-IV, temporary tracheostomy, and pectoralis myocutaneous (PM) PF reconstruction instead of the initially planned osteo-cutaneous fibula FF.

Patient 3 presented a laryngeal SCC rT4aN2c post-chemoradiation (initially cT4aN2c), and underwent total laryngectomy extending to the right base of tongue and piriform sinus, and to the already existing tracheostoma with surrounding skin, total thyroidectomy, and bilateral neck dissection II-VI. Initially scheduled for an anterolateral thigh FF, he underwent reconstruction with a PM PF.

In order to reduce operating times, flap harvesting was performed simultaneously to the resection phase in all cases, with the goal of keeping the operating time under 5 h.

Patient 1 and 2 were discharged on postoperative day 7 and 9, respectively, without complications. At phone consultation speech intelligibility was excellent, and the patients had returned to normal diet. Both were scheduled for adjuvant radiotherapy.

For patient 3 the initial postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient's discharge was scheduled on postoperative day 11. However, a fistula was radiologically revealed by video fluoroscopy the day before discharge. The patient remained admitted and compressive dressing was applied daily. The fistula was solved after 10 days of conservative treatment.

The COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy has posed a critical challenge to the health care system. General recommendations for evaluation and surgery of the head and neck during the COVID-19 pandemic have been recently depicted by Givi et al. [2], although there has been no specific focus on reconstructive policy to date.

According to previous Institutional policy, all patients of the series were considered SARS-CoV-2 free based on the analysis of potential sources of contact, the absence of symptoms consistent with active infection and the evaluation of preoperative chest radiogram; these requirements to undergo elective surgery were recently implemented by adding a mandatory negative nasopharyngeal swab test.

Our dedicated anesthesiologists requested that we minimize surgical times in order to be available for management of the dramatic challenge represented by the current pandemic. Moreover, no postoperative ICU surveillance was available.

In this scenario, the greater advantage provided by PF is the relevant shortening of operative times, as reported by several series in literature; longer surgical time is also a significant factor for the development of postoperative complications and prolonged hospitalization [3,4]. Of note, the simultaneous rising of the flap during cancer resection was possible also with the PM flap.

Although suboptimal in specific cases (i.e. mandibular reconstruction), PF can provide satisfactory functional and esthetic results, in particular for lateral defects in weak patients.

The only complication experienced in the series was the development of a pharyngo-cutaneous fistula in Patient 3, who was at high risk in view of a poor nutritional status and persistent smoke habit. A multicentric review [5] showed no differences in terms of fistula formation between FF and PF after salvage laryngectomy with partial pharyngectomy, although in our opinion the selection of PM flap reconstruction was also appropriate because a PF can better withstand conservative management with compressive dressing in case of fistula [6].

The reshaping of the reconstructive strategy allowed us to save precious resources, without jeopardizing the overall validity of surgery and functional results. Our reconstructive viewpoint should be taken into consideration when facing a massive pandemic outbreak such as that experienced in Lombardy.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Grasselli G., Zangrillo A., Zanella A., Antonelli M., Cabrini L., Castelli A. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Givi B., Schiff B.A., Chinn S.B., Clayburgh D., Gopalakrishna Iyer N., Jalisi S. Safety recommendations for evaluation and surgery of the head and neck during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2020.0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahieu R., Colletti G., Bonomo P., Parrinello G., Iavarone A., Dolivet G. Head and neck reconstruction with pedicled flaps in the free flap era. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2016;36:459–468. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deganello A., Leemans C.R. The infrahyoid flap: a comprehensive review of an often overlooked reconstructive method. Oral Oncol. 2014;50:704–710. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Microvascular Committee of the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery Salvage laryngectomy and laryngopharyngectomy: multicenter review of outcomes associated with a reconstructive approach. Head Neck. 2019;41:16–29. doi: 10.1002/hed.25192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Busoni M., Deganello A., Gallo O. Pharyngocutaneous fistula following total laryngectomy: analysis of risk factors, prognosis and treatment modalities. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2015;35:400–405. doi: 10.14639/0392-100X-626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]