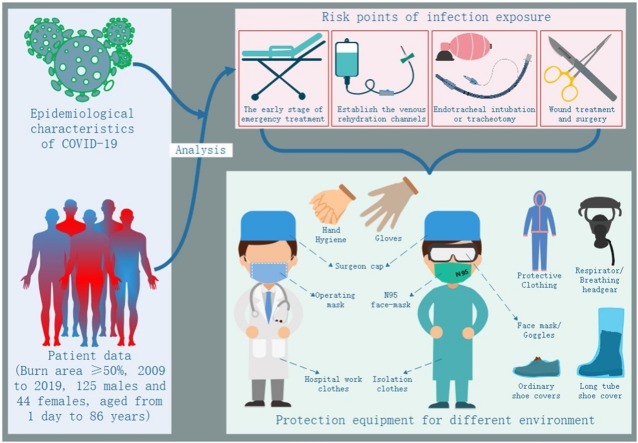

Graphical abstract

Abbreviations: ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; COVID-19, coronavirus disease; ICTV, International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; WHO, World Health Organization; IgM, immunoglobulin M; IgG, immunoglobulin G; NGS, next-generation sequencing

Keywords: Burns, COVID-19, Healthcare-associated infections, Epidemic prevention and control, Exposure risk, Protection

Abstract

Epidemic prevention and control measures for the new coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has achieved significant results. As of 8 April 2020, 22,073 infection cases of COVID-19 among healthcare workers from 52 countries had been reported to WHO. COVID-19 has strong infectivity, high transmission speeds, and causes serious infection among healthcare worker. Burns are an acute-care condition, and burn treatment needs to be initiated before COVID-19 infection status can be excluded. The key step to infection prevention is to identify risk points of infection exposure, strengthen the protection against those risk points, and formulate an appropriate diagnosis and treatment protocol. Following an in-depth study of the latest literature on COVID-19 diagnosis and treatment, we reviewed the protocols surrounding hospitalization of patients with extensive burns (area≥50 %) in our hospital from February 2009 to February 2019 and, in accordance with the epidemiological characteristics of COVID-19, developed an algorithm for protection during diagnosis and treatment of burns. Therefore, the aspects of medical protection and the diagnosis and treatment of burns appear to be particularly important during the prevention and control of the COVID-19. This algorithm was followed for 4 patients who received emergency treatment in February 2020 and were hospitalized. All healthcare worker were protected according to the three-tiered protective measures, and there was no nosocomial infection. During the COVID-19 epidemic, the early stages of emergency treatment for patients with extensive burns requiring the establishment of venous access for rehydration, endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy, wound treatment, and surgery are the risk points for exposure to infection. The implementation of effective, appropriate-grade protection and formulation of practical treatment protocols can increase protection of healthcare worke and reduce the risk of COVID-19 infection exposure.

1. Introduction

Since December 2019, a new type of coronavirus has continued to spread throughout the country in China [1,2]. Globally, nearly 1.5 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 have now been reported to the World Health Organization (WHO), and more than 92,000 deaths [3]. After initial virus-typing tests, the WHO officially named the new coronavirus causing the Wuhan pneumonia epidemic the "2019 new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2)" on 12 January 2020. And the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) announced an official nomenclature of the new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) as the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, SARS-CoV-2). On the same day, the WHO announced that the official name of the disease caused by the virus is coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [4].

On 20 January 2020, China’s “National Infectious Diseases Law” was amended to make COVID-19 a Class B notifiable disease and the management of a Class A infectious diseases has been adopted [5]. A WHO–China joint mission shared findings and recommendations on 25 February 2020, wherein 3387 cases of COVID-19 was reported from among medical staff in 476 medical institutions in China, of whom 25 died [6]. As of 8 April 2020, 22,073 infection cases of COVID-19 among healthcare workers from 52 countries had been reported to WHO [7]. These data show that COVID-19 has strong infectivity, high transmission speed, and can cause serious infections among healthcare worker.

Burns are an acute-care condition, and the treatment of patients with extensive burns poses a race against the time. Therefore, burn treatments need to be initiated before COVID-19 infection status can be excluded. The key step is to identify the risk points of infection exposure, strengthen the protection against those risk points, and formulate an appropriate diagnosis and treatment process. Improper protection can easily lead to the occurrence of medical infections. Therefore, the aspects of medical protection and the diagnosis and treatment of burns appear to be particularly important during the prevention and control of the COVID-19.

To found the identify risk points of infection exposure, strengthen the protection against those risk points, and formulate an appropriate diagnosis and treatment protocol. Following an in-depth study of the latest literature on COVID-19 diagnosis and treatment, we reviewed the protocols surrounding hospitalization of patients with extensive burns in our hospital and, in accordance with the epidemiological characteristics of COVID-19, developed an algorithm for protection during diagnosis and treatment of burn patients.

2. Materials and methods

From 2009 to February 2019, we reviewed and analyzed the treatment conditions and protocols followed in patients with (area≥50 %) burns patients Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital. To identify the risk points of infection exposure during burn treatment according to the epidemiological characteristics of COVID-19, we obtained patient data, including the sex, age, diagnosis, admission time, operation time, endotracheal intubation or tracheotomy operation, central vein puncture operation, anesthesia mode, etc., from the medical records department of the hospital.

2.1. Laboratory confirmation

Laboratory confirmation of the SARS-CoV-2 was achieved through the concerted efforts of the Guangdong Center for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC),Guangzhou ardent clinical laboratory. The RT-PCR assay was conducted in accordance with the protocol established by the World Health Organization [8].

2.2. Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± SD whereas qualitative variables were presented as frequencies. The chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was carried out for data analysis. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiological characteristics

3.1.1. Source of infection

The source of infection seen so far is mainly patients with new type of coronavirus infection. Asymptomatic infection can also be a source of infection [9].

3.1.2. Route of transmission

Respiratory droplets and close contact transmission are the main transmission routes. It is possible to propagate through aerosols when exposed to high concentration aerosols for a long time in a relatively closed environment. Because novel coronavirus can be isolated from feces and urine, attention should be paid to the spread of aerosols or contacts caused by environmental pollution [10].

3.1.3. Susceptible population

The population is generally susceptible

3.2. Clinical characteristics

The incubation period is 1–14 days, and is frequently 3–7 days. The main symptoms are fever, fatigue, and dry cough. A few patients have symptoms such as nasal congestion, runny nose, sore throat, and diarrhea. Severe patients often develop dyspnea and/or hypoxemia 1 week after disease onset and progress rapidly to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), septic shock, refractory metabolic acidosis, and coagulopathy. Notably, the course of severe and critically ill patients can be marked by moderate to low fever, or they may even be afebrile. Mildly affected patients show only low fever and mild fatigue without symptoms of pneumonia. Judging from the current cases, most patients have a good prognosis, and a few patients do become critically ill. The prognosis for the elderly and patients with chronic underlying disease is poor. Fortunately, symptoms in children are relatively mild.

3.3. Laboratory investigations

The peripheral white blood cell count in patients with early onset was normal or decreased, the lymphocyte count was normal or decreased, and some patients had elevated liver enzymes, muscle enzymes, and myoglobin; some critically ill patients showed increased troponin levels. In most patients, C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) increased, and procalcitonin level was normal. In some patients, d-dimer increased and peripheral blood lymphocyte decreased progressively. Most severe and critically ill patients present showed elevated levels of inflammatory factors. SARS-CoV-2 was detected by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and/or next-generation sequencing (NGS) in nasopharyngeal swabs, sputum and other lower respiratory secretions, blood, and feces. The virus was more accurately detected in lower respiratory tract samples (sputum or airway extracts). Samples were sent for examination as soon as possible after collection.

3.3.1. Serological examination

Most of the specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies of SARS-CoV-2 began to test positive 3–5 days after disease onset. The titer of IgG antibody in the recovery period was 4 times higher than that in the acute period.

3.3.2. Chest imaging

In the early stages, there were multiple, small, patchy shadows and interstitial changes on imaging, especially in the lateral zone of the lung. Later on, patients developed multiple ground-glass shadows and infiltrates in both lungs. In severe cases, lung consolidation may occur, although pleural effusion is rare.

3.4. Diagnostic criteria for suspected cases

Any one of the epidemiological histories with any two of the clinical manifestations, or three of the clinical manifestations without epidemiological history are suspected cases.

3.4.1. Epidemiological history

Details of the epidemiological history and clinical manifestations in patients with suspect COVID-19 are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Diagnosis and treatment of 4 suspected cases of COVID-19.

| Patient | A | B | C | D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | F | M | F | M | |

| Age (years) | 22 | 44 | 34 | 53 | |

| Reception time | 2020/2/8 Emergency | 2020/2/8 Emergency | 2020/2/11 Emergency | 2020/2/24 Emergency | |

| Diagnosis | 1. < 10 % burns2. Pulmonary hypertension | Necrotizing fasciitis | Flame burn 85 % TBSA | Flame burn 65 % TBSA | |

| Epidemiological history | ① | – | – | – | – |

| ② | – | + | – | – | |

| ③ | + | – | – | – | |

| ④ | – | – | – | – | |

| Clinical manifestation | ① | – | – | + | + |

| ② | – | – | + | – | |

| ③ | + | + | + | + | |

| COVID-19 nucleic acid detection | + | – | – | – | |

| Consultation expert conclusion | Asymptomatic carrier of SARS-CoV-2 virus | Suspected cases of COVID-19 | Suspected cases of COVID-19 | Exclude suspected cases | |

| Transfer after consultation | Negative pressure ward of infection department | Isolated ward of infection department | Burn isolated ward | Burn ward | |

| Endotracheal intubation | – | – | √ | – | |

| Skin puncture | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Wound treatment | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Protection level | Tertiary protection | Secondary protection | Tertiary protection | Primary protection | |

1. Epidemiological history.

a. History of travel or residence in Wuhan and surrounding areas or other communities with reported cases within 14 days preceding illness onset.

b. History of contact with COVID-19-infected persons (positive nucleic acid test) within 14 days preceding symptom onset.

c. Patients with fever or respiratory symptoms from Wuhan and surrounding areas, or from communities with reported cases within 14 days preceding illness onset.

d. Aggregation onset (Two or more cases of fever and/or respiratory symptoms within the preceding 2 weeks in small areas, such as family, office, school class).

2. Clinical manifestations.

a. Fever and/or respiratory symptoms.

b. With the above imaging characteristics of pneumonia.

c. Total number of white blood cells normal or decreased, or normal or decreased lymphocyte count in early-stage disease.

3. Diagnostic criteria for suspected cases.

Any one of the epidemiological histories with any two of the clinical manifestations, or three of the clinical manifestations without epidemiological history are suspected cases.

3.5. Diagnostic criteria for confirmed cases

Suspected cases were diagnosed as confirmed cases based on one of the following evidences: a. real-time fluorescent RT-PCR detection of SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid positive; b. Gene sequencing highly homologous to known SARS-CoV-2; and c. SARS-CoV-2-specific IgM and IgG antibodies positive. The specific serum IgG antibody levels against SARS-CoV-2 changed from negative to positive or increased 4 times or more in the recovery period than in the acute period.

We reviewed the "Regulations on Biosafety Management of Pathogenic Microbiology Laboratories” [11], and developed an algorithm for the protection of healthcare worker during burn treatment. The above protective measures and treatment processes were carried out for 4 patients who required emergency treatment in February 2020 and were hospitalized (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Protective equipment.

| Protection degree with specific environment | Protective Equipment |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hand Hygiene | Surgeon cap | Respiratory protection |

Face mask/ Goggles | Medical rubber glove | Body protection |

Lower limb protection |

||||||

| Operating mask | N95 face-mask | Respirator/ Breathing headgear | Hospital work clothes | Isolation clothes | Protective Clothing | Ordinary shoe covers | Long tube shoe cover | |||||

| Routine protection (Daily work of all medical staff) | + | – | + | – | – | – | ± | + | – | – | – | – |

| Primary protection (Stay in the ward of febrile patients (without contact with patients)) | + | + | + * | – | – | + | + | + | – | ± | – | |

| Secondary protection(General diagnosis and treatment for suspected or confirmed patients) | + | + | / | + | – | ± | + | + | + * | + * | ||

| Tertiary protection(Aerosol-generating procedures for suspected or confirmed patients) | + | + | / | + * | + | Double gloves | + | / | + | / | + | |

“+”Required; “-”Not required (except for exceptional circumstances); “±”Use as needed; “/”Insufficient protection; “+ *”Protective products for selective use / simultaneous use according to the actual conditions of medical institutions. "General diagnosis and treatment": This refers to non-aerosol-generating operations (aerosol-generating operations include sputum suction, respiratory tract, and endotracheal intubation).

4. Theory

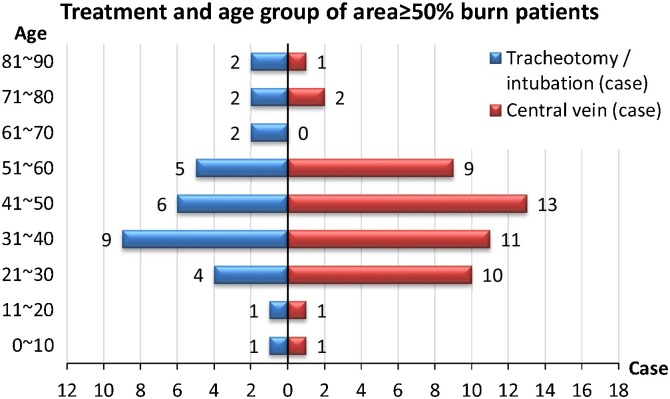

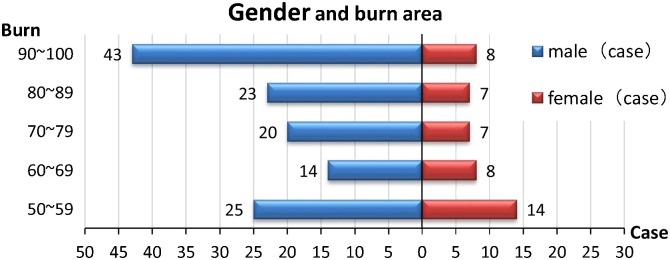

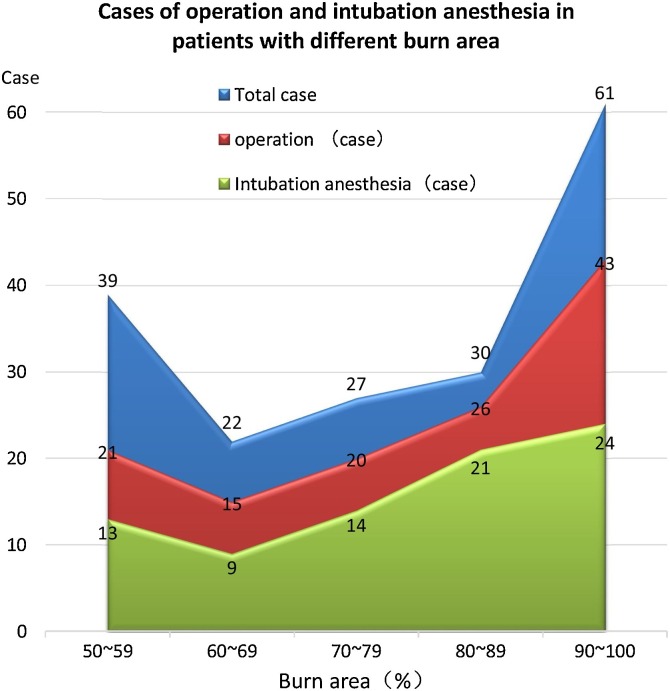

1. From 2009–2019, 169 patients with burns (area≥50 %) were admitted, including 125 males and 44 females (age range: 1 day to 86 years [mean ± SD, 34.51 ± 20.11 years]), and 94.67 % (160/169) were cured and discharged ( Fig. 1 ). In the early stage of burn treatment (<14 days after burn injury), 100 % (169 / 169) of the patients received intravenous rehydration through venous canulae, 28.40 % (48/169) required central venous canulae; 18.93 % (32/169) of the patients underwent tracheal intubation or tracheostomy ( Fig. 2 ); 100 % (169/169) of patients underwent wound treatment; 63.31 % (107/169) of the patients underwent surgical treatment, and 82.24 % (88/107) of them required general anesthesia and underwent tracheal intubation (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 1.

Treatment and age group of area≥50 % burn patients.

Fig. 2.

Gender and burn area.

Fig. 3.

Operation and anesthesia intubation.

2. During the COVID-19 epidemic, requirements for medical staff protection and a diagnosis and treatment flowchart for burn treatment were formulated (Table 2 ). As of 29 February 2020, the abovementioned protective measures and procedures were implemented for 4 patients suspected of COVID-19 infection in the emergency department. One patient was diagnosed as an asymptomatic carrier of the COVID-19 virus and was treated in the negative-pressure ward of the infectious diseases department. Two patients were suspected cases of COVID-19 and needed to be isolated for 14 days. CT examination of lung and tests for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid examination were negative when tested at two different timepoints. After the COVID-19 infection was ruled out, two patients were transferred back to the burn ward. One patient was considered free of COVID-19 infection and received treatment in the burn ward (Table 3 ). During the diagnosis and treatment of all four patients, all the healthcare worker carried out protective measures according to the three-level protection requirements, without contracting nosocomial infection.

Table 2.

Standard protection protocol during burn treatment.

| Specific environment | Protection degree | Protective Equipment |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hand Hygiene | Surgeon cap | Respiratory protection |

Face mask/ Goggles | Medical rubber glove | Body protection |

Lower limb protection |

||||||||

| Operating mask | N95 face-mask | Respirator/ Breathing headgear |

Hospital work clothes | Isolation clothes | Protective Clothing | Ordinary shoe covers | Long tube shoe cover | |||||||

| Burn clinic and emergency | Without contact with patients | Routine | + | – | + | – | – | – | ± | + | – | – | – | – |

| General diagnosis and treatment | Secondary | + | + | / | + | – | ± | + | + | + * | + * | |||

| Burn ward and ICU | Without contact with patients | Primary | + | + | + * | – | – | + | + | + | – | ± | – | |

| General diagnosis and treatment | Secondary | + | + | / | + | – | ± | + | + | + * | + * | |||

| Perform an aerosol-generating operation | Tertiary | + | + | / | + * | + | Double gloves | + | / | + | / | + | ||

| Burn operation | Patients excluded from infection | According to the routine of operating room | ||||||||||||

| Non-suspected emergency patients | Secondary | + | + | / | + | – | ± | + | + | + * | + * | |||

| Confirmed/highly suspect patient | Tertiary | + | + | / | + * | + | Double gloves | + | / | + | / | + | ||

| Patient screening (sputum culture, pharyngeal swab collection) | ||||||||||||||

“+”Required; “-”Not required (except for exceptional circumstances); “±”Use as needed; “/”Insufficient protection; “+ *”Protective products for selective use / simultaneous use according to the actual conditions of medical institutions. "General diagnosis and treatment": This refers to non-aerosol-generating operations(Aerosol-generating operations include sputum suction, respiratory tract, and endotracheal intubation).

5. Discussion

SARS-CoV-2 is highly infectious and pathogenic. COVID-19 is a new and sudden acute infectious disease that can be spread through person-to-person transmission. At present, COVID-19 has no significant known curative treatment. After the virus invades the human body, it mainly destroys the respiratory tract and causes pneumonia, which may lead to respiratory failure and endanger life [[12], [13], [14]].

In Wang’s paper, as of 28 January 2020, of the 138 patients with COVID-19 in a general hospital at Wuhan, 57 (41.3 %) were presumed to have been infected in the hospital, including 17 patients (12.3 %) who were already hospitalized for other reasons and 40 healthcare workers (29 %). Of the infected healthcare workers, 31 (77.5 %) worked in the general wards, 7 (17.5 %) in the emergency department, and 2 (5%) in the ICU [15]. More than 10 healthcare workers in the surgical department were presumed to have been infected by the first COVID-19 patient. Patient-to-patient and healthcare-worker-to-healthcare-worker transmission was presumed to have occurred. Therefore, the general department, especially the surgical department, is a department with high incidence of nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 infection. According to an article by the China Center for Disease Control and prevention, as of 11 February 2020, there were 3019 cases of COVID-19 infection among healthcare worker in 422 medical institutions in China, of which 5 died [16]. COVID-19 is more virulent than SARS and Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome (MERS). In the WHO–China joint mission shared findings and recommendations of 25 February 2020, 3387 cases of COVID-19 infection among healthcare worker in 476 medical institutions in China were reported, of which 25 died [6]. As of 8 April 2020, 22,073 infection cases of COVID-19 among healthcare workers from 52 countries had been reported to WHO [7]. These data show that COVID-19 has strong infectivity, high transmission speed, and can cause serious infection among healthcare worker. The lack of COVID-19 research in the early stages of the disease is one reason for healthcare worker to have neglected protection. In the middle stage of the disease, it was confirmed that COVID-19 is transmitted through respiratory droplets, close contact, and aerosol transmission. However, due to a large number of patients beyond Wuhan's urban medical allocation, the supply of medical protective materials is seriously insufficient, which leads to the continuous occurrence of nosocomial infections [17]. In fact, a large number of healthcare worker infected in a short period easily increase the work pressure and psychological pressures on other healthcare worker. Therefore, it is very important to identify the risk points of infection exposure, strengthen the protection of healthcare worker, and develop a standard protocol for the diagnosis and treatment.

5.1. Exposure risk points of COVID-19 infection in early treatment of burns

5.1.1. The process of establishing intravenous fluid channels

Patients with extensive burns need to receive a large amount of fluid resuscitation after being hospitalized. In our study, 100 % (169/169) of the patients underwent establishment of venous-access channels, of which 28.40 % (48/169) simultaneously received a central venous catheter. At this time, burn patients could not have been quickly screened for COVID-19 infection. When performing a peripheral or a central venipuncture to establish a fluid replacement channel, healthcare worker need to have close contact with the patient. In fact, close contact is one of the main routes of transmission of COVID-19. Therefore, the process of establishing venous access channels is the earliest point of exposure to COVID-19 infection in the early treatment of burn patients.

5.1.2. Endotracheal intubation or tracheotomy

Patients with extensive burns are prone to systemic edema, and neck edema causes narrowing of the trachea. When combined with respiratory burns, the airway mucosa is damaged, and throat edema increases the possibility of asphyxia. Early treatment often requires endotracheal intubation or tracheotomy, and if necessary, ventilator-assisted breathing. In the process of endotracheal intubation or tracheotomy, healthcare worker must have come into contact with the patient’s respiratory droplets. However, droplet transmission is the main mode of transmission of COVID-19. After endotracheal intubation or tracheal intubation, sputum aspiration and other related operations are easy routes to contact aerosols. In our study, 18.93 % (32/169) of severely burned patients underwent endotracheal intubation or tracheotomy. Because most of the patients with severe burns are treated in the burns ICU, the more difficult tracheotomy is undertaken at the bedside. Compared with the operating conditions and equipment in the operating room, bedside procedures are deficient in terms of safety protocols, and the neck of patients often has tissue edema, which necessitates longer tracheostomy times than in normal procedures. The risk of exposure to infection is thus increased. Therefore, the establishment of endotracheal intubation or tracheotomy is the highest risk-exposure point for COVID-19 infection in the early treatment of burn patients.

5.1.3. Wound treatment and surgical procedures

The function of the skin barrier is destroyed in patients with extensive burns, which leads to wound exposure and wound exudation. Early treatment requires topical drugs and wound dressings. This procedure will be performed every 2–3 days until the wound is completely closed. And the time of wound treatment was positively correlated with the size of burn wounds. In our study, 100 % (169/169) of the patients underwent wound management. Early burn escharectomy and skin grafting are also common operations for burn patients. When general anesthesia with tracheal intubation is needed, medical staff come into contact not only with patients, but also with patients' respiratory droplets and aerosols. In our study, 63.31 %% (107/169) patients underwent surgical treatment within 14 days after injury, of which 82.24 % (88/107) underwent general anesthesia through tracheal intubation. In the process of wound treatment and operation, healthcare worker would not only operate in a relatively closed environment, but also closely experience contact with the patient's body fluids, droplets, and aerosols. In the process of wound treatment and operation, healthcare worker not only need to operate in a relatively closed environment, but also closely contact with the patient's body fluids. Both intimate contact with patients' body fluids and long-time exposure to high concentrations of aerosols in a relatively closed environment are routes of transmission of COVID-19. Therefore, the process of wound treatment and surgery is the highest risk point of COVID-19 infection exposure in the early treatment of burn patients.

5.2. Protection and treatment protocols for burns in the epidemic-prevention period of COVID-19

5.2.1. Protocol for treatment of severe fever and burns

Fever is common in patients with extensive burns. Combined with respiratory tract burns, the patient can progress to have lung and bronchial injury. Because of systemic inflammatory response syndrome and large amount of rehydration treatment, burn patients are prone to pulmonary edema. X-ray examination of both lungs in burn patients showed multiple, small, spots and interstitial changes. This is very similar to the early chest-imaging findings of COVID-19. Therefore, it is not easy to differentiate and diagnose the two conditions clinically. In our study, 2 cases of large area burns were treated in emergency, 2 cases were febrile, and 1 case had multiple, small, spots on chest imaging.

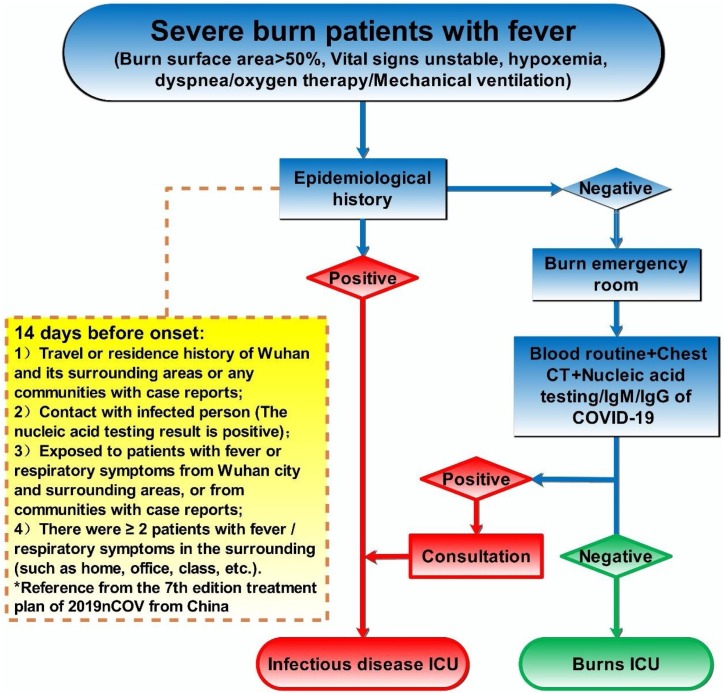

Quickly complete lung CT and blood routine examinations for new patients who are admitted to the emergency ward and screening, based on a new COVID-19-infected pneumonia diagnosis and treatment plan (Trial version 7), should be combined with clinical symptoms and epidemiological history. Healthcare worker should establish secondary protective measures. As all new patients are routinely admitted to the emergency ward or the emergency ICU for regional isolation, the departmental healthcare worker should take primary protections. If it is necessary to perform invasive procedures in these patients, healthcare worker should undertake secondary protection. For the suspected or confirmed NCP patients, healthcare worker should strictly follow the emergency treatment plan, and promptly seek a consultation with an infectious diseases specialist, modify the treatment plan, and transfer the patient to the infectious diseases specialized ward. In cases where patients need to be treated with close contact, healthcare worker need to establish tertiary protection (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Schematic representing the treatment process of burn patients with high fever.

5.2.2. Protection of endotracheal intubation and tracheotomy

Patients with extensive burns are prone to anasarca or neck edema leading to tracheal compression stenosis. When combined with respiratory burns, damage to airway mucosa, and tracheal edema, there is an increased possibility of asphyxia. Intubation or tracheostomy is often needed during early treatment in these patients. In this study, 1 burn patient needed endotracheal intubation and ventilator-assisted ventilation.

Related literature suggests that medical procedures, such as endotracheal intubation, tracheotomy, mechanical ventilation, and fiberoptic bronchoscopy, can increase the risk of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV transmission [18]. Therefore, according to the requirements of the WHO "Infection Prevention And Control During Health Care When Novel Coronavirus (NCoV) Infection Is Suspected" interim guidance and the opinions of the clinical expert committee, healthcare worker need to undertake tertiary protection (including hand hygiene, use of personal protective equipment, respiratory hygiene, needlestick prevention, cleaning of medical supplies, and treatment of medical waste, etc.) For suspected/confirmed patients of COVID-19, droplet isolation and contact isolation are required, and air-isolation measures need to be undertaken for medical procedures that can generate aerosols [19]. For patients who have not been confirmed free of COVID-19 infection, medical procedures can be carried out in the negative-pressure ward; alternatively, these procedures can be conducted in a well-ventilated ward to avoid operations in the positive-pressure ward.

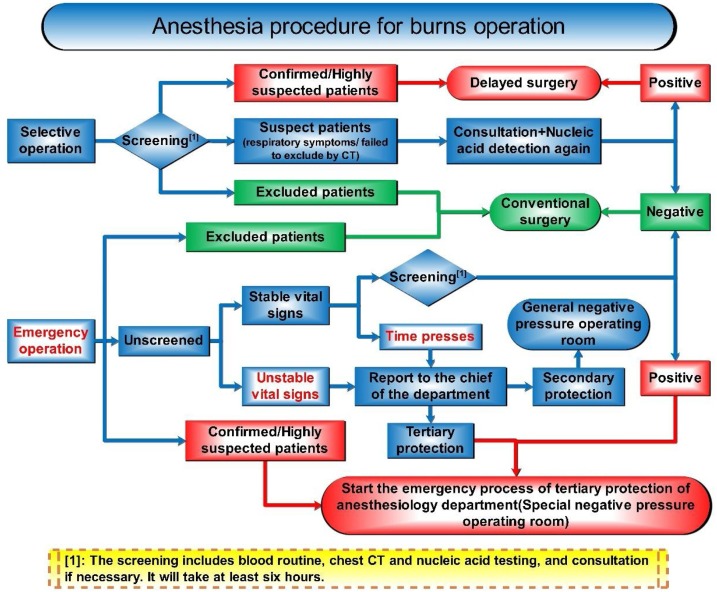

5.2.3. Surgical anesthesia process

For emergency surgery, complete lung CT and blood routine examinations are necessary immediately before surgery, and COVID-19 screening should be undertaken on the basis of clinical symptoms and epidemiology. Thereafter, strict adherence to emergency protocols for patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should be enforced. Relevant protective tasks should be carried out during the perioperative period and intraoperatively, and all items and surfaces should be disinfected and sterilized in strict adherence to the disinfection protocol. Patients should be isolated in a single room during hospitalization. During dressing change and ward rounds, attention is needed toward the implementation of a series of protective measures against nosocomial infections. For patients who are not confirmed to be free of COVID-19 infection, emergency procedures such as general anesthesia of endotracheal intubation should be undertaken in the negative-pressure operating room, and the healthcare worker need to establish tertiary protective measures (Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 5.

Schematic of the burns surgical anesthesia process.

In general, COVID-19 is an acute respiratory disease with diverse transmission routes and a high transmission rate. During the epidemic period, the treatment of burns patients not confirmed to be free of COVID-19 infection, the processes of establishing intravenous access, endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy, wound treatment, and surgery are risk points of infection exposure. The implementation of effective, appropriate-grade protection and development of practical treatment procedures will increase the protection levels for healthcare worker and reduce the risk of COVID-19 infection exposure.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province [grant number A2017004, A2016108], Science and Technology Project of Guangzhou City [grant number 201804010232], and Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province [grant number 2018A0303130040]. The authors gratefully acknowledge Elsevier Premium Language Editing Services for the English edited.

References

- 1.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J., Zhao X., Huang B., Shi W., Lu R., Niu P., Zhan F., Ma X., Wang D., Xu W., Wu G., Gao G.F., Tan W. China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team, A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perlman S. Another decade, another coronavirus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:760–762. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2001126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2020. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19 - 10 April.https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---10-april-2020 10 April 2020 (accessed 10 April 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorbalenya A.E., Baker S.C., Baric R.S., de Groot R.J., Drosten C., Gulyaeva A.A., Haagmans B.L., Lauber C., Leontovich A.M., Neuman B.W., Penzar D., Perlman S., Poon L.L.M., Samborskiy D., Sidorov I.A., Sola I., Ziebuhr J. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus – the species and its viruses, a statement of the Coronavirus Study Group. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.07.937862. (accessed 11 Feb 2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China . 2020. Announcement of the National Health Committee of the People’s Republic of China, 20 January.http://www.nhc.gov.cn/jkj/s7916/202001/44a3b8245e8049d2837a4f27529cd386.shtml (Accessed 20 Jan 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2020. WHO-China Joint Mission Shares Findings and Recommendations 25 February.https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pdf 25 February 2020 (Accessed 25 Feb 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)Situation Report – 82.https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200411-sitrep-82-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=74a5d15_2 11 April 2020 (Accessed 11 April 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2020. Laboratory Diagnostics for Novel Coronavirus.(https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus/laboratory-diagnostics-for-novel-coronavirus) 6 February (Accessed 6 February 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, Interpretation of "New Coronavirus Pneumonia Diagnosis and Treatment Scheme (Trial Version 7)" [EB/OL], (accessed 4 Feb 2020) http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7652m/202003/a31191442e29474b98bfed5579d5af95.shtml.

- 10.Jiang Y., Wang H., Chen L., He J., Chen L., Liu Y., Hu X., Li A., Liu S., Zhang P., Zou H., Hua S. Clinical data on hospital environmental hygiene monitoring and medical staffs protection during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak. bioRxiv. 2020 https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.02.25.20028043v1.full.pdf (Accessed 27 Feb 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liuyi L., Yuxiu G., Liubo Z., et al. Regulation for prevention and control of healthcare associated infection of airborne transmission disease in healthcare facilities. Chin. J. Infect. Control. 2017;16:490–492. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-9638.2017.05.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan J.F., Yuan S., Kok K.H., To K.K.-W., Chu H., Yang J., Xing F., Liu J., Yip C.C.-Y., Poon R.W.-S., Tsoi H.-W., Lo S.K.-F., Chan K.-H., Poon V.K.-M., Chan W.-M., Ip J.D., Cai J.-P., Cheng V.C.-C., Chen H., Hui C.K.-M., Yuen K.-Y. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., Cheng Z., Yu T., Xia J., Wei Y., Wu W., Xie X., Yin W., Li H., Liu M., Xiao Y., Gao H., Guo L., Xie J., Wang G., Jiang R., Gao Z., Jin Q., Wang J., Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y., Qiu Y., Wang J., Liu Y., Wei Y., Xia J., Yu T., Zhang X., Zhang L. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu Z., Zhang J., Wang B., Xiang H., Cheng Z., Xiong Y., Zhao Y., Li Y., Wang X., Peng Z. China, JAMA; 2020. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-infected Pneumonia in Wuhan. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Chin. J. Epidemiol. 2020;41:145–151. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. (Accessed 24 Feb 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaki A.M., Van Boheemen S., Bestebroer T.M., Osterhaus A.D., Fouchier R.A. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization . 2020. Infection Prevention and Control During Health Care When Novel Coronavirus (nCoV) Infection Is Suspected (Interim Guidance), 25 January.https://www.who.int/publications-detail/infection-prevention-and-control-during-health-care-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected-20200125 (Accessed 25 Jan 2020) [Google Scholar]