Abstract

Policies that improve the socioeconomic conditions of families have been identified as one of the most promising strategies to prevent child maltreatment, particularly neglect. In this study, we examined the impact of integrated Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) and child welfare (CW) systems on child maltreatment-related hospitalizations and Child Protective Services investigations and substantiations in nine counties in Colorado from 1996 to 2014. Regression analyses showed TANF-CW integration was associated with subsequent year, but not second-year, increases rates of substantiated child maltreatment overall and neglect specifically (that is, there was no longer a difference in the rate two years after the change in integration). Neither unemployment nor the one- or two-year lagged effect of integration were significant for investigations or child maltreatment-related hospitalizations. Increased opportunities to interact with a family in crisis using an integrated case management model may help explain these findings. Implications for future research are discussed.

Keywords: Child abuse, child neglect; TANF; Child welfare policy; Evaluation

1. Introduction

Child maltreatment (CM) is a serious public health issue in the United States, with one in four children experiencing some form of maltreatment before the age of 18 (Finkelhor, Turner, Shattuck, & Hamby, 2015). All forms of CM, including physical, sexual and emotional abuse and neglect, can affect long-term brain development and leave children vulnerable to a range of short- and long-term mental and physical health problems, such as substance abuse, obesity, and heart disease (Felitti et al., 1998; Leeb, Lewis, & Zolotor, 2011; Shonkoff, Boyce, & McEwen, 2009). Given the magnitude of the problem and the burden it places on the health of the public, the primary prevention of CM has risen to a significant public health priority. A key strategy in preventing CM is the promotion of safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments, particularly through policies that support children, parents, and families (Fortson, Klevens, Merrick, Gilbert, & Alexander, 2016).

Policies that improve the socioeconomic conditions of families have been identified as one of the most promising strategies to prevent CM (Fortson et al., 2016; Klevens, Barnett, Florence, & Moore, 2015; Paxson & Waldfogel, 2002, 2003). Policies such as strengthening household financial security through Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) or tax credits have the potential to prevent CM by improving parents’ mental health, caregiving behaviors, family dynamics and ability to satisfy children’s basic needs (e.g., food, shelter) (Cancian, Yang, & Slack, 2013; Raissian & Bullinger, 2017). Such interventions may be especially important in the prevention of neglect, the form of CM which has the strongest relationship with poverty (Drake & Jonson-Reid, 2014; Sedlak et al., 2010). In fact, Raissian and Bullinger (2017) found that a $1 increase in minimum wage ($2080 per year) was associated with a 10% reduction in Child Protective Service (CPS) reports of CM, particularly neglect. On the other hand, lifetime welfare limits were found to be associated with increases in substantiated cases of CPS reports of neglect (Paxson & Waldfogel, 2003). These studies point to the key role that economic assistance may play in the prevention of CM, particularly neglect.

Economic assistance to families is often administered through the TANF program, the hallmark Federal policy enacted through the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (replacing Aid to Families with Dependent Children [AFDC]). States receive block grants to design and operate programs that accomplish one of the purposes of the TANF program, including providing aid to needy families so that children can be cared for at home (Administration for Children and Families [ACF], 2017) – potentially reducing the risk for child welfare (CW) involvement. It has been hypothesized by scholars and government agencies that collaboration and cross-system integration between the TANF and CW systems will lead to better outcomes across both systems, potentially preventing some TANF-involved families from becoming involved with the CW system (ACF, 2016; Ehrle, Andrews Scarcella, & Geen, 2004). Cross-system integration (a broad range of activities that range from development of a shared vision to joint planning, cross-training, cross-agency team case management and shared data) may facilitate pooling of limited resources, sharing of expertise among staff, reduction in duplication of efforts, and sharing information about families’ needs to develop the more responsive approach to supporting families (Ahonen et al., 2016). Cross-system integration and related efficiencies may be particularly important in the context of the Great Recession (2007–2009), which lead many states to seek cost savings by reducing TANF administrative and program costs (Brown & Derr, 2015).

In the current study, we examine the relationship between changes in the level of integration in the TANF-CW systems on CM in nine counties in the state of Colorado. In Colorado, CW services are county-administered and state-supervised by the Colorado Department of Human Services (CDHS) Division of Child Welfare. It is in this policy context that counties can create innovation in program and service delivery, including integrated TANF-CW system models. El Paso County, Colorado, has served as a model of the innovative use of existing welfare policies since the late 1990s (Berns & Drake, 1999; Capizzano, Koralek, Botsko, & Bess, 2001; Hutson, 2003) and is central to the current study. Starting in the late 1990s, El Paso County implemented policy reform that supported integrated CW-TANF systems focused on providing family-centered services, regardless of how families came to the attention of the CDHS. A case study of the El Paso County experience documented the process whereby integration occurred (e.g., implementation of new vision statements, staff trainings, and case planning) and the context that supported this change – predominately visionary leadership, flexibility and cultural change (Hutson, 2003). After initiating new policies and procedures, El Paso County reportedly saw a reduction in abuse and neglect court filings (Hutson, 2003). Importantly, however, this case study was not in the context of a study design that would allow for inferences about the links between integration and CM. Furthermore, it is important to note that despite funding pressures, Colorado retained a largely similar pre- and post- economic recession TANF program – at least in terms of staffing and budget. During this period, Colorado only lost one full-time position at the state level (versus, e.g., New Hampshire, which experienced a 50% reduction in its statewide eligibility staff) and saw a less than 1% reduction in its TANF budget (versus, e.g., 50% in Illinois) (Brown & Derr, 2015). Thus, promising case study findings – paired with the relative staffing stability of its TANF program – make Colorado an ideal state in which to examine TANF-CW integration.

Leveraging the rich documentation of the El Paso experience and other similar counties in Colorado, the goal of the current study is to rigorously evaluate the impact of TANF-CW integration on CM in nine Colorado counties. We extend prior work, which has predominately focused on either describing the nature of TANF-CW collaboration and/or integration (e.g., Tungate, 2008), and the implementation of policies and programmatic efforts to increase agency integration (e.g., Ahonen et al., 2016; Ehrle et al., 2004), by examining a range of CM indicators following changes in TANF-CW integration. Specifically, we seek to answer the question: Does increased TANF-CW integration result in reduced rates of CM outcomes (CPS investigations and substantiations, and CM-related hospitalizations)? Understanding the impact of TANF-CW system integration on CM is in line with the public health goal of identifying effective population-based prevention policies to prevent CM (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2015).

2. Method

In the present study, we leverage “natural” variation in the level of integration in nine Colorado counties between 1995 and 2015 to estimate the effects of TANF-CW integration on CM. We focus on Colorado counties with the most similar demographic and geographic characteristics to El Paso County, including a population size of greater than 100,000 persons. Population size is important characteristic to consider as Colorado includes many counties that are quite rural, have very small population size, and therefore have much smaller child welfare caseloads. In these smaller counties, extant data is less stable for trend examinations, and very unique social services systems are designed to respond to small caseloads using minimal financial resources since funding is often based on per capita or caseload formulas. The nine included counties include Adams, Boulder, Denver, Douglas, El Paso, Jefferson, Larimer, Mesa, and Pueblo.

2.1. Integration status

TANF-CW integration status is the primary independent variable. Although servive integration is often cited as a desirable service characteristic across many human service fields, there is surprisingly little agreement about how to define this construct (Browne, Kingston, Grdisa, & Markle-Reid, 2007; Fletcher et al., 2009; Gajda & Koliba, 2007; Marek, Brock, & Savla, 2015; Woodland & Hutton, 2012), particularly with regard to CW and TANF systems and services (Horwath & Morrison, 2007). Thus, guided by the literature on domains relevant to service integration across sectors (Bai, Wells, & Hillemeier, 2009; Ehrle et al., 2004; Horwath & Morrison, 2007), the literature on defining and measuring the integration continuum (Ahgren & Axxelson, 2005; Browne et al., 2007; Fletcher et al., 2009; Gajda, 2004; Gajda & Koliba, 2007; Horwath & Morrison, 2007; Woodland & Hutton, 2012), and descriptions of El Paso County’s approach to integration (Berns & Drake, 1999; Hutson, 2003), we derived a study definition of CW-TANF service integration. This definition (the coordination of TANF and child welfare activities, procedures, and policies that link services across service boundaries for newly identified clients, dual-system clients, or clients with multiple co-occurring needs) served to both help articulate our key independent variable but to help respondents in our study understand exactly what we meant by integration. Building from the literature cited above and resulting definition, we developed the TANF-CW Integration Implementation Index (TANF-CW III), a measurement tool designed to systematically assess the extent of integration across ten domains (see Table 1). The TANF-CW III was refined following a pilot of the full study protocol in one county.2

Table 1.

Domains and scoring of the TANF-Child Welfare Integration Implementation Index (TANF-CW III).

| Level of Integration | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Less Intense | More Intense | ||||

| Domain Score | Independence | Communication/ Awareness |

Cooperation | Collaboration | Integration |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|

Vision/Mission of Agency (or Division) The extent to which the vision and mission of an organization is shared throughout the organization and across partnerships |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leadership/Managerial The extent to which leadership drives collaboration between TANF and child welfare |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Client-Serving Staff The extent to which staff works together to provide integrated services to TANF or child welfare or dual-system clients1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Funding The extent to which the financial resources of agencies have been pooled to support jointly administered staff, programs, or services in support of CW and TANF integration activities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cross-Training The extent to which staff members from each agency are trained to provide services to TANF or child welfare or dual-system clients |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Data Systems The extent to which agencies use a single, shared data and reporting system that enables staff to access data on clients of both agencies, as needed |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Decision Making The extent to which management and leadership of child welfare and TANF are involved in a wide range of shared decision making that affects clients served by both agencies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Case Planning and Management The extent to which a single case plan is co-developed and co-managed |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Programs and Services The extent to which programs or services are jointly planned (i.e., direct or contracted services) and designed to the meet the spectrum of needs for clients seen in child welfare and TANF caseloads, thereby reducing duplication of efforts. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Committees or Workgroups Related to Integration The extent to which cross-agency committees and workgroups are formed with the purpose of increasing and maintaining integrated programs and services |

|

|

|

|

|

These clients are simultaneously involved in both TANF and child welfare.

Shared funding is a single source of funding used jointly.

Pooled funding is when multiple flexible funding sources are combined into one funding pool.

Blended funding is when funds provided by multiple entities are pooled and do not have any restrictions on their use. This is more flexible than braided funding because the funds are allocated collectively and can be used however they are needed to achieve the goals of the partnership. This may also be referred to as “decategorization.”

Braided funding is when multiple entities provide funds to a partnership, but each entity’s funds maintain their distinct requirements. The use of the funds is clearly defined and cannot change. This also may be referred to as “coordination.”

In-kind indicates that the support is non-monetary (e.g., volunteered time, non-cash donations).

Wraparound services means an arrangement of individualized, coordinated, family-driven care to meet complex needs of children and families who are involved with several child- and family-serving systems (e.g., child welfare, TANF). Wraparound services aim to emphasize the strengths of the child and family and to deliver coordinated, unconditional services to achieve positive outcomes while maintaining the child and family safety in the community.

Family-centered practice is a way of working with families, both formally and informally, across service systems to enhance their capacity to care for and protect their children. It focuses on children’s safety and needs within the context of their families and communities and builds on families’ strengths to achieve optimal outcomes. Families are defined broadly to include birth, blended, kinship, and foster and adoptive families.

We populated the TANF-CW III retrospectively for each study year (1996 through 2014) by triangulating multiple data sources: in-person interviews, brief surveys completed by all interviewees, and a document review. Each data source is described in more detail below.

2.1.1. Interviews

Interview guides were developed by the researchers to assess the historical and current level of system integration between TANF and CW. The interview guides (available upon request) were tailored for respondent type and included: County Director of Human Services, Leaders/Managers, Case Managers, Data Managers, Allied Staff and Agency External Partners. The interviews, semi-structured in nature, lasted approximately one hour and included questions about the current and historical nature of system integration. The questions in the guides were aligned to each domain of the TANF-CW III. About 12–15 in-person interviews were conducted in each county and the sample was segmented by level of leadership and type of service program to obtain a comprehensive look at integration. All efforts were made to identify staff with long tenure in each county who would be able to offer historical insight. Two members of the research team were present for each interview.

2.1.2. Surveys

A brief survey about TANF and CW activities, procedures, and policies (available upon request) was electronically self-administered to all interviewees in each county. Like the interview, survey questions were designed to provide a quantitative assessment of both current and historical levels of integration on each of the TANF-CW III domains. The survey was informed by work of Tungate (2008), who developed a brief self-administered survey for the purposes of describing the extent and nature of TANF-CW service coordination and collaboration.

2.1.3. Document review

The research team reviewed a wide range of county-level documents relevant to TANF and CW programs and policies, provided to the study team by county-level points of contact. Documents reviewed include, but are not limited to, annual reports, training requirements, attendance records for trainings, contracts for programs and services, case planning documents, memoranda of understanding with partners, and policy and mission statements. The documents were coded by TANF-CW III domain.

2.1.4. Integration index scoring

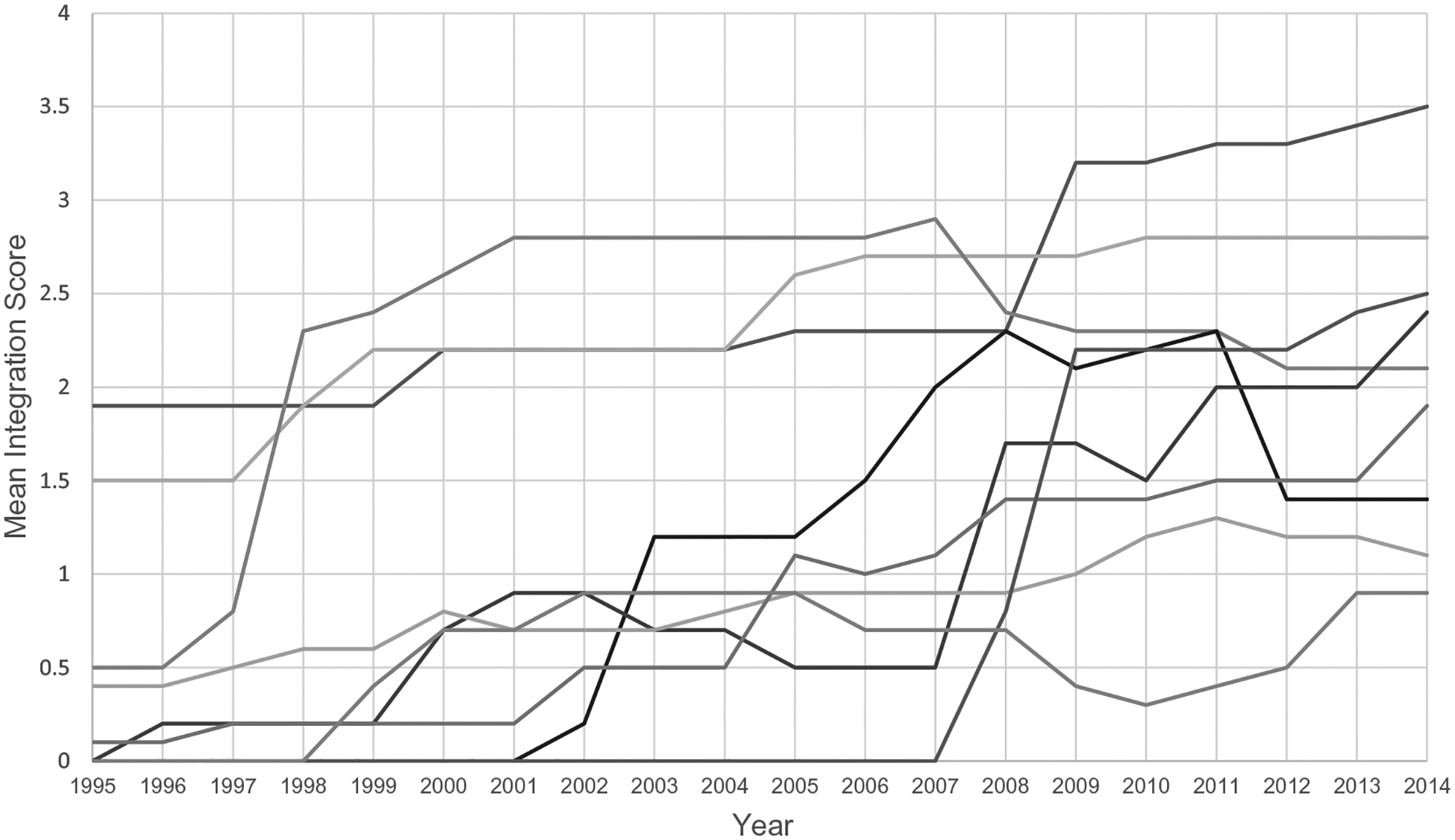

Using the domains of the TANF-CW III, we assessed each county’s level of implementation of integrated TANF–CW service model for each study year. Like other work examining organizational integration (e.g., Browne et al., 2007; Woodland & Hutton, 2012), each domain was scored on an integration continuum: Independence (0), Communication (1), Cooperation (2), Collaboration (3), and Integration (4). Table 1 describes scoring indicators for each domain. Two researchers – those present for the interviews – independently completed the TANF-CW III for each county, and then met with a third study team member to compare scores, discuss discrepancies, and reach consensus on the final score for each domain for each study year. The scores were then combined across all domains, yielding an average integration score for each year in each county to use as our independent variable.3 The scoring of each county on the TANF-CW III served to differentiate levels of integration in each county by study year in the outcome analyses. (See Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mean TANF-CW III integration scores, by study county, 1995–2014.

Note: Each line represents one of nine Colorado counties included in analyses.

2.2. Child maltreatment outcomes

For the purposes of this study, we used a combination of measures to estimate rates of CM. Schorr & Marchand (2007) advocate for evaluating rates of CM using a combination of measures, because policies, procedural changes, and other unrelated issues can influence involvement with the child welfare system. CM reports may be influenced by high profile cases, norms for mandated reporters, and family involvement with social services agencies more generally (Ross & Vandivere, 2009). CM substantiations, on the other hand, have other limitations, including variations in the legal system or in social work practice across communities and staffing issues that influence determinations of substantiation (Institute of Medicine, National Research Council, 2014). By itself, each measure is biased and prone to fluctuations in response to policy; therefore, in this study, we explore the following CM outcomes: substantiated CM – as measured by the substantiated victimization rate and substantiated case rate; CM investigations – as measured by the rate of CM referrals; and hospital zations for CM – as measured by hospitalizations for suspected or definitive CM. Although overlapping (e.g., substantiated cases also include referrals), these indicators potentially offer unique information as outcomes (Institute of Medicine & National Research Council, 2014).

These indicators were compiled from multiple sources, including the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2004–2014), Colorado KIDS COUNT reports (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2015), Colorado Trails, and the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project-State Inpatient Databases (HCUP-SID, 2014). The full range of CM outcomes explored for this analysis are described below.

2.2.1. CM substantiations – substantiated case rate

We used two data sources to estimate the substantiated case rate (number of cases substantiated per 1000 children) for both overall maltreatment and neglect4 specifically. First, NCANDS child files from 2002 to 2014 were used to assess rates of CM over time, by county. The NCANDS is a federally sponsored national data collection effort that tracks the number and nature of CM reporting each year within the United States. Second, because a few of the early years in our time series preceded the tracking of data in NCANDS, we worked with the Colorado Children’s Campaign to obtain data from the archive of Colorado KIDS COUNT reports. These data served as a source for CM substantiations for the years in our study (1996–2000) that preceded the systematic collection and reporting of CM data in state or Federal systems such as NCANDS.

2.2.2. CM substantiations – substantiated victimization rate

To estimate the victimization rate (number of child victims per 1000 children) for both overall CM and neglect specifically, we used NCANDS files from 2002 to 2014. The victimization rate includes a child each time they were found to be a “victim” (i.e., designations of substantiated, indicated, or an alternative response). For example, a child with three substantiated victimization incidents and two indicated victimization incidents counts as a total of five victimizations.

2.2.3. CM investigations – rate of referrals

Data from Colorado’s automated case management system for child welfare (Colorado Trails) were used to assess the number of reports or referrals for CM for the years 2002–2013. Data were obtained from the CDHS Division of Child Welfare and are not otherwise available in publicly available datasets such as NCANDS.

2.2.4. Rate of children hospitalized

HCUP-SID data were used to produce counts of the number of children who were hospitalized each year for suspected or definitive CM. The HCUP-SID dataset includes information on all hospitalizations across the country, including the length of stay, patient demographics, and primary diagnosis as captured by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM), the official system of assigning codes to diagnoses and procedures associated with hospital utilization in the United States. The classification of ICD-9 codes used for suspected CM were drawn from the work of Schnitzer, Slusher, Kruse, and Tarleton (2011), who developed a scheme based on their efforts to improve the accuracy of medical data for public health surveillance of CM. ICD-9-CM codes for definitive CM were based on CDC’s uniform definitions (Leeb, Paulozzi, Melanson, Simon, & Arias, 2008). Using these ICD-9-CM codes, we computed maltreatment-related hospitalization (including both suspected and definitive CM) rates per 100,000 children for the years 1998–2013 For the denominator of rates in all outcomes, population estimates were computed using the data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s annual county-level estimates of population by age groups. For years prior to 2010, we used data from the intercensal population estimates, which uses actual population data from the decennial census to adjust the annual estimates. For years 2011–2014, we used the post-census population estimates, which estimates populations after a census by combining the decennial census data from the previous census with birth, death, migration, and net international immigration data. These census data allowed for computation of county-level CM indicators expressed as a rate per 1000 children under the age of 18 (except for hospitalization rates which are expressed as a rate per 100,000)

2.3. Control variables

When evaluating the impact of TANF-CW integration, we explored the effects of three measures of community-level socioeconomic conditions that could potentially influence both TANF participation and CM rates: unemployment rate, poverty rate, and median household income. For the years 1995–2014, poverty and household income were pulled from the Census Bureau’s Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates (SAIPE) and unemployment (percentage of adults in the workforce who were unemployed during the year) from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Local Area Unemployment Statistics (LAUS). Because poverty, unemployment, and median household income are conceptually and empirically related, each of the three measures were examined in separate models predicting the effect of integration on each outcome of interest. Unemployment was the only economic variable that had explanatory power in any of the models; therefore, it is the only control retained in the final models.

3. Data analyses

We estimated the effect of the level of TANF-CW integration on CM, taking advantage of the “natural” variation of the level of integration within study counties over time. The statistical model controls for either observed or unobserved confounding characteristics (differences across counties that may explain differences in both the level of integration and the level of CM) as long as these characteristics remain relatively constant over the period analyzed. To that end, a set of so called “fixed-effects,” one for each county, was included in the regression. Additional covariates were included to account for time-varying differences between counties. In particular, we included the contemporaneous unemployment rate, which was found to make a significant difference on model fit. Finally, to capture both immediate and longer term-effects of integration, we included indicators of the level of integration during the prior one, two and three or more years.

The model was estimated using the first differencing approach (i.e., changes in the response variable were regressed on the change in the regressors), a method that accounts for the county unobserved effect, and can eliminate residuals serial correlation (Wooldridge, 2010). All analyses were implemented with R (R Core Team, 2015), the “plm” package for panel data analysis (Croissant & Millo, 2008) and the package “sandwich” to obtain robust standard errors (Lumley & Zeileis, 2007). The regression equation for the final model is detailed in Appendix A.

The research team examined the integration scores multiple ways to assess the relationship between level of integration and CM outcomes. We expected that the effects of integration would likely not be immediate, and instead have an impact that was delayed by a year or more depending on the particular outcome. Therefore, we created lagged versions of the integration index to estimate the effect at one year following integration and at two years following integration. We estimated a series of models predicting the effect of integration (measured using a one-year and two-year lag) and the unemployment rate on each of the identified CM outcomes. Alternative specifications including additional covariates, differences in linear trends on maltreatment rates across counties, and change over time affecting all counties simultaneously were also considered but none resulted in a significantly improved fit to the data.

4. Results

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and number of county-years of data for variables included in the analysis. Across years and counties, TANF-CW Integration scores ranged from 0 to 3.5; percentage unemployed range from 1.4 to 10.4%; rates of substantiated cases ranged from 0.6 to 11.3 per 1000 children; substantiated victimization rates ranged from 0.6 to 18.4 per 1000 children; and hospitalization rates ranged from 1.4 to 10.4 per 100,000 children. As expected, neglect comprised a substantial proportion of CM reports, cited in the majority of Colorado CM cases over the study period (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2015; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010a, 2010b, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for predictors and outcomes.

| Mean (Standard Deviation) | Number of County Years | |

|---|---|---|

| Predictors | ||

| TANF-Child Welfare Integration Implementation Index Total Score | 1.3 (1.0) | 180 |

| Unemployment Rate | 5.3 (2.0) | 180 |

| Outcomes | ||

| Substantiated case rate (all types of CM) (× 1000) | 5.4 (2.3) | 161 |

| Substantiated child victimization rate (all types of CM) (× 1000) | 8.3 (3.7) | 117 |

| Substantiated child victimization rate (neglect) (× 1000) | 5.7 (3.1) | 117 |

| Child maltreatment referral rate (all types of CM) (× 1000) | 61.0 (21.7) | 136 |

| Maltreatment-related hospitalization rate (suspected or definitive child maltreatment) (× 100,000) | 81.8 (32.1) | 144 |

Table 3 presents the results of models estimating the effect of integration on the four CM outcomes, using unemployment as a covariate. Specifically, this table presents the parameter estimates and significance levels (p-values) for each parameter estimate resulting from adjusting standard errors for unequal variance across counties and assuming a common variance within each county.

Table 3.

Models predicting the effect of integration on child maltreatment outcomes.

| Predictors | Substantiated Case Rate | Substantiated Victim Rate (All Types of CM) | Substantiated Victim Rate (Neglect) | Referral Rate | Hospitalizations Due to Child Maltreatment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | β | p-value | |

| Unemployment | −0.04 | 0.61 | 0.01 | 0.95 | 0.04 | 0.76 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.062 | 0.98 |

| TANF-CW Integration (1-year lag) | 0.68 | 0.01 | 1.36 | 0.00 | 0.91 | 0.05 | 2.71 | 0.17 | 4.54 | 0.46 |

| TANF-CW Integration (2-year lag) | 0.19 | 0.44 | 0.25 | 0.57 | 0.29 | 0.51 | −0.98 | 0.48 | −7.13 | 0.49 |

Note. Standard errors adjusted for unequal variance across counties and assuming a common variance within each county.

4.1. CM substantiations – substantiated case rate

In the model examining the rate of substantiated cases, there was a significant positive effect of integration, measured with a one-year lag. In other words, changes in the level of integration score of one unit (e.g. from independence to communication or from cooperation to collaboration) were followed the subsequent year by an increase in the rate substantiated cases of one additional case per 1471 children. Neither unemployment nor the two-year lagged effect of integration was significant when predicting the rate of substantiated cases.

4.2. CM substantiations – substantiated victimization rate

In the model examining the substantiated victimization rate, there was a positive effect of integration, measured with a one-year lag, on the rate of substantiated victims overall, as well as for substantiated victims of neglect. Neither unemployment nor the two-year lagged effect of integration was significant for either of these outcomes.

4.3. CM Investigations – Rate of Referrals

In the model examining the rate of referrals for CM, there were no significant effects of integration when measured with a one-year or two-year lag. Similarly, the effects of unemployment were also not significant when predicting the rate of referrals for CM.

4.4. Rate of Children Hospitalized

Finally, in the model examining the effect of TANF-CW integration on hospitalizations due to suspected and/or definitive maltreatment, the effect was not significant in either a one-year or two-year lag. The effects of unemployment were also not significant when predicting the rate of CM-related hospitalizations.

5. Discussion

The current study examined the relationship between TANF-CW integration on CM (CPS investigations and substantiations, and CM-related hospitalizations) in nine Colorado counties. We leveraged the “natural” variation of the level of integration within study counties over time and used a robust design and analytic strategies to isolate effects of integration on county-level CM outcomes. Our analyses considered socioeconomic variables conditions that could potentially influence both TANF participation and CM rates. Contrary to expectations, we did not find that increased levels of TANF–CW system integration results in reductions in CM outcomes of interest. Rather, the findings indicate that integration was associated with subsequent year increases rates of substantiated CM (overall) and neglect specifically. Although these findings are different from the experience described in Hutson’s (2003) case study, there are potential explanations. It is possible that the integration model itself may influence the likelihood of substantiation upon investigation. Changing the way of doing business, even if it represents an improved model and is intended to more effectively support families who are experiencing challenges, might also subject a family to more scrutiny. Increased opportunities to interact with a family in crisis using an integrated case management model could result in a fuller understanding of the family’s situation and enough evidence when investigating CM to lead to substantiation. As is typically the case when relying on CPS data, an increase in rates of CM may suggest an improvement in the surveillance system or an actual increase in CM within the population. The lack of effects on CM hospitalizations (not influenced by greater scrutiny in either TANF or child welfare system), however, suggests possible surveillance bias. If an integrated approach is substantiating more cases of actual CM, this is a desirable end state as it offers the potential to safeguard vulnerable children from harm using the best available evidence (Fortson et al., 2016).

As noted, the positive effect of integration on overall CM and neglect substantiations was found only when assessed using a one-year, but not two-year, lag in the effect on outcomes (i.e. there was no longer a difference in the rate two years after the change in integration). Thus, integration of activities across TANF–CW systems appears to have a relatively quick effect on trends in several CM outcomes. This may reflect a training effect; caseworkers may initially be more vigilant and this may wane over time if additional trainings are not offered. It is also possible that increased vigilance post-integration may not be sustainable in the economic context covering a portion of our study period. As noted earlier, during the economic recession, Colorado saw few reductions in TANF program staff and funding (Brown & Derr, 2015). However, from 2007 to 2012, Colorado’s TANF and SNAP average monthly cases increased by approximately 25% and 100%, respectively. Therefore, during the economic downturn, caseworkers had increasingly larger caseloads – without relief in administrative duties regarding federal requirements for timeliness and determining initial and ongoing eligibility in multiple programs (Brown & Derr, 2015). Understanding effects of integration over time will be an important area for future work to pursue.

5.1. Limitations and future directions

The present study provides a valuable contribution to understanding coordinated case planning by offering a systematic assessment of how TANF–CW integration affects CM-related outcomes. Nonetheless, it is important to note that our study provides a “first look” at TANF-CW integration in Colorado. We acknowledge that this is a complicated, multi-dimensional topic. For example, over time, TANF has served a decreasing share of eligible families. In 2014, for every 100 Colorado families in poverty, only 34 received cash assistance from TANF — down from 66 families when TANF was first enacted in 1996 (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2018). Although TANF has helped reduce the depth of poverty, the benefits may be too low to lift many families out of deep poverty (families living with incomes below half the poverty line) (Ben-Shalom, Moffitt, & Scholz, 2012; Sherman, 2009). Our study focused on the policy context and analyses performed with county-level variables; although we considered the unemployment rate, poverty rate, and median household income, future research could examine these variables at the family-level. Examination of family-level deep poverty and the impact of integration for those families that are struggling most to satisfy children’s basic needs is an important area for future work to explore.

Related, future research could examine components of the TANF program vis-à-vis county CW-TANF integration. Across Colorado counties, providing families cash assistance has generally been a priority; in the face of limited budgets, this has meant that counties have reduced eligibility and provider reimbursement rates in their child care subsidy programs (Buck, Cucili, & Baker, 2013). Without access to child care subsidies, working families may be unable to afford quality child care programs which offer the kind of early environment that supports safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments that decreases the risk of CM (Fortson et al., 2016; Klevens et al., 2015). Along these lines, research on the impact of multi-system and program integration including and beyond TANF and CW may also help elucidate study findings. Evidence suggests that programs as Supplemental Nutrition and Assistance Program (SNAP), Unemployment Insurance, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and the Child Tax Credit are important components of the safety net (Moffitt, 2013).

Our findings should be also considered in the context of several other limitations. First, our analysis was limited by the use of county-level data on instances of CM known to CPS, rather than household-level data and all instances of CM occurring within homes. Thus, it is difficult to examine the pathway by which integration may affect the experience of children and families (Paxson & Waldfogel, 2003). We acknowledge that many other factors may be at play within the life of a family – including context of a community/county, and the nature of the systems that serve families (e.g., changes in children’s health insurance programs) – all of which could impact CM outcomes.

Second, our study includes a limited number of units (9 counties) with fewer than 20 years in the study period (1996–2014), and an even more limited number of county-years with complete data on all CM outcomes of interest. Specifically, we did not have data for the entire time series (data for the earliest years of our analysis for substantiated victimization rate and number of reports or referral were not available). Further, the substantiated case rate was obtained by using two sources of data (Colorado KIDS COUNT reports for the years 1996–2000 and NCANDS for 2002–2014). A comparison of rates for years when both data sources were available (i.e., 2003, 2004, and 2006) showed the earlier system, KIDS COUNT, reporting consistently higher rates of CM (by 31 to 35%) when compared to NCANDS. As integration scores increased over time, changing to a system reporting lower rates for the later years might have increased the probability of showing a decrease in substantiated rates associated with integration. However, the opposite was observed.

The limitations of child welfare administrative data are described thoroughly elsewhere (e.g., Brownell & Jutte, 2013) and not easily overcome. Federal CW data tracking systems were just being developed in the mid-1990s and participation in reporting was not required for many more years. At the state level, the Colorado Division of Child Welfare changed to a new data management system in 2003, and data collected prior to that year are either not available or of limited reliability. For these reasons, we did not rely on any single indicator and pulled data from numerous sources, including a broad range of ICD-9 codes – including codes suggestive of neglect (Schnitzer et al., 2011). Future research should continue to consider a broad range of sources (e.g., outpatient healthcare, education, law enforcement) and additional CW-relevant outcomes (e.g., placement changes) to estimate the effects of integration on CM. Along these lines, future research may want to consider comparing rates of CM outcomes to other community-level variables to isolate the effect of integration on CM specifically. We attempted to pursue this approach post hoc by comparing rates of CM to the outcome of intimate partner violence, pulling the incidents (number of adult victims per 1000 adults) for each county from the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS; Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, 2015). However, there were five counties where information on IPV victimization was missing from NIBRS and others that were missing partial data from some of the years in the series. Future research could explore other community-level outcomes (e.g., hospitalizations not due to CM) where more complete data may be available.

Third, there is no “gold-standard” measure of system integration. Our team sought to develop a comprehensive, evidence-informed assessment of the history of TANF–CW integration using multiple methods and data sources. Nonetheless, there is likely unknown bias in our assessment of levels of integration in each county – most especially in the first decade of the time series. It is possible that the Index missed important aspects of integration, which could lead to imprecise measurement of this key variable. Even with a strong measurement tool, however, the data sources available to inform the measurement are subject to recall biases and limited documentation of system integration activities. We believe these issues may most likely lead to under-estimating levels of system integration, especially in the early years of the study. If true, this may have the effect of inaccurately categorizing some counties for some study years as being less integrated in their service delivery than in fact they were. Future research may want to continue to refine the measurement of system integration and seek to validate and/or improve upon our methods of measuring integration. Such approaches as abstraction of case files and prospective case study designs may help refine measurement in this area and further our ability to test its effects with stronger confidence.

Finally, future research may want to replicate our analyses with larger county samples in other states with similar policy structures to Colorado, or with Tribal TANF grantees, who have the authority to independently administer TANF programs (see Ahonen et al., 2016 for a description of grantees funded to improve service coordination between Tribal TANF and CW). Such studies could offer corroboration or refute the findings we have presented using Colorado counties and add to the evidence base for policy strategies that may prevent CM.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the leadership and staff who agreed to participate in this study including those in county-level executive management and county-level TANF and child welfare divisions in the participating counties. We also thank the leadership at the Colorado Department of Human Services for their assistance with outreach to counties during the recruitment process.

Financial

This study was supported by an award to ICF International (CDC Contract 200-2012-52326). Writing and editing supported in part by RTI International.

Appendix A. Statistical model

We estimated the effect of the level of TANF-CW integration on child maltreatment (CM), taking advantage of the “natural” variation of the level of integration within study counties over time. Specifically, we relied on the following statistical model.

For CM rate y in county i during year t, we proposed that:

, i = 1, 2, …, I, t = 4, 5, …, T,

where:

I and T are the total number of counties and years, respectively;

xit−1 is the level of TANF-CW integration the previous year;

xit−2 is the level of TANF-CW integration two years before then; and

is the cumulative moving average of the level of TANF-CW integration in the previous three years;

wit is the unemployment rate in the county the same year;

ci is represents time-constant differences across counties, potentially related with the level of integration (sometimes termed ‘fixed effect’);

uit is a random error unrelated with eitherxit−1, xit−2, , or wit;

The parameters β1, β2 and β3 capture systematic differences in CM rates associated with past changes in the level of integration in the county, respectively, changes during the previous year, two years ago, or sometime before. The parameter β4 captures systematic differences in CM rates associated with simultaneous changes in unemployment. The model was estimated using the first differencing approach (i.e., changes in the response variable were regressed on the change in the regressors), a method that accounts for the county unobserved effect, ci, and can eliminate residuals serial correlation (Wooldridge, 2010).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval and informed consent

This study was conducted with approval from ICF International’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB Control Number 0920–1025). Informed consent was obtained from the participants after the nature of the procedure were fully explained.

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer

Publisher's Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Following the pilot, all interview guides were slightly revised for clarity purposes. For example, questions were simplified and redundant questions were removed. In addition, a new interview guide was created specifically for individuals who serve as data managers or staff who work directly with CW and/or TANF data systems.

We also computed a dichotomous version which considered average values 2 and above as “integrated” and values below 2 as “not integrated.” The results of models using the dichotomous coding largely mirrored the results using the average scores. For this reason, and because the CW-TANF III was originally conceptualized and scored as a scale, we decided to present the results using the average TANF-CW III score.

Colorado defines neglect as parental failure to take actions to provide adequate food, clothing, shelter, medical care, supervision, or education, thereby endangering the well-being of the child (Colorado Rev. Stat. §§ 19–1–103; 19–3–102). Colorado does not include a poverty exemption in their statutory definition of neglect.

References

- Administration for Children and Families [ACF] (2017). About TANF. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/programs/tanf/about.

- Administration for Children and Families [ACF]. ACF (2016). Collaboration with TANF/Public Assistance. Retrieved from https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/management/practice-improvement/collaboration/tanf/.

- Ahgren B, & Axelsson R (2005). Evaluating integrated health care: a model for measurement. International Journal of Integrated Care, 5(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahonen P, Buckless B, Hafford C, Keating K, Keene K, Morales J, & Park CC (2016). Study of Coordination of Tribal TANF and Child Welfare Services: Final Report. OPRE Report #2016–52. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Retrieved from: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/ttcwfinalreport2016_b508.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Annie E. Casey foundation. KIDS COUNT data center (2015). Retrieved from https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data#CO/2/0/char/0.

- Bai Y, Wells R, & Hillemeier MM (2009). Coordination between child welfare agencies and mental health service providers, children’s service use, and outcomes. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33, 372–381. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shalom Y, Moffitt R, & Scholz JK (2012). An assessment of the effect of anti-poverty programs in the United States In Jefferson P (Ed.). Oxford handbook of the economics of poverty. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berns DA, & Drake BJ (1999). Combining child welfare and welfare reform at a local level. Policy & Practice of Public Human Services, 57(1), 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Brown E, & Derr MK (2015). Serving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) recipients in a post-recession environment. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation; Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/ib_tanf_needyfamilies_021815_final_0.PDF. [Google Scholar]

- Browne G, Kingston D, Grdisa V, & Markle-Reid M (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of integrated human service networks for evaluation. International Journal of Integrated Care, 7 10.5334/ijic.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell MD, & Jutte DP (2013). Administrative data linkage as a tool for child maltreatment research. Child abuse & neglect, 37(2–3), 120–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck B, Cucili PL, & Baker R (2013). Moving families forward: An introduction to TANF in Colorado during the recession. Colorado Children’s Campaign. Retrieved from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED559529.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cancian M, Yang M, & Slack KS (2013). The effect of additional child support income on the risk of child maltreatment. Social Service Review, 87, 417–437. 10.1086/671929. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capizzano J, Koralek R, Botsko C, & Bess R (2001). Recent changes in Colorado welfare and work, child care, and child welfare systems. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; Retrieved from: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/61326/310299-Recent-Changes-in-Colorado-Welfare-and-Work-Child-Care-and-Child-Welfare-Systems.PDF. [Google Scholar]

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (2018). TANF financial assistance to poor families has lost ground in Colorado. Washington, DC: Author; Retrieved from https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/tanf_trends_co.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Core Team, R. (2015). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Croissant Y, & Millo G (2008). Panel data econometrics in R: The plm package. Journal of Statistical Software, 27, 1–43. 10.18637/jss.v027.i02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drake B, & Jonson-Reid M (2014). Poverty and child maltreatment In Korbin JE, & Krugman RD (Eds.). Handbook of Child Maltreatment (pp. 131–148). Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrle J, Andrews Scarcella C, & Geen R (2004). Teaming up: Collaboration between welfare and child welfare agencies since welfare reform. Children and Youth Services Review, 26, 265–285. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. American Journal of Prevention Medicine, 14, 245–258. 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, & Hamby SL (2015). Prevalence of childhood exposure to violence, crime, and abuse: Results from the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence. JAMA Pediatrics, 169, 746–754. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher BW, Lehman WEK, Wexler HK, Melnick G, Taxman FS, & Young DW (2009). Measuring collaboration and integration activities in criminal justice and substance abuse treatment agencies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 103, S54–S64. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortson BL, Klevens J, Merrick MT, Gilbert LK, & Alexander SP (2016). Preventing child abuse and neglect: A technical package for policy, norm, and programmatic activities. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and. Prevention; Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/can-prevention-technical-package.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gajda R, & Koliba C (2007). Evaluating the imperative of intraorganizational collaboration: A school improvement perspective. American Journal of Evaluation, 28, 26–44. 10.1177/1098214006296198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gajda R (2004). Utilizing Collaboration Theory to Evaluate Strategic Alliances. American Journal of Evaluation, 25(1), 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. (2014). Overview of the Statewide Inpatient Databases. Retrieved from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/sidoverview.jsp

- Horwath J, & Morrison T (2007). Collaboration, integration and change in children’s services: Critical issues and key ingredients. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31, 55–69. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson R (2003). A vision for eliminating poverty and family violence: Transforming child welfare and TANF in El Paso County, Colorado. Center for Law and Social Policy: Policy Brief, Child Welfare Series, 1, 1–7. Retrieved from: https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/public/resources-and-publications/files/0108.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. (2015). National Incident-Based Reporting System. Retrieved from: http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/NACJD/NIBRS/

- Institute of Medicine & National Research Council (2014). New directions in child abuse and neglect research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 10.17226/18331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klevens J, Barnett SB, Florence C, & Moore D (2015). Exploring policies for the reduction of child physical abuse and neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect, 40, 1–11. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeb RT, Lewis T, & Zolotor AJ (2011). A review of physical and mental health consequences of child abuse and neglect and implications for practice. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 5, 454–468. 10.1177/1559827611410266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leeb RT, Paulozzi L, Melanson C, Simon T, & Arias I (2008). Atlanta. GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. [Google Scholar]

- Lumley T, & Zeileis A (2007). Sandwich: Model-robust standard error estimation for cross-sectional, time series and longitudinal data. R package version 2.0–2 http://CRAN.R-project.org.

- Marek LI, Brock D-JP, & Savla J (2015). Evaluating collaboration for effectiveness: Conceptualization and measurement. American Journal of Evaluation, 36, 67–85. 10.1177/1098214014531068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt RA (2013). The Great recession and the social safety net. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 650, 143–166. 10.1177/0002716213499532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2015). CDC Injury Center Research Priorities. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/pdfs/researchpriorities/cdc-injury-research-priorities.pdf

- Paxson C, & Waldfogel J (2002). Work, welfare and child maltreatment. Journal of Labor Economics, 20, 435–474. 10.1086/339609. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paxson C, & Waldfogel J (2003). Welfare reforms, family resources, and child maltreatment. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 22, 85–113. 10.1002/pam.10097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raissian KM, & Bullinger LR (2017). Money matters: Does the minimum wage affect child maltreatment rates? Children and Youth Services Review, 72, 60–70. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.09.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ross T, & Vandivere S (2009). Indicators for child maltreatment prevention programs. Washington, DC: Quality Improvement Center on Early Childhood. [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzer PG, Slusher PL, Kruse RL, & Tarleton MM (2011). Identification of ICD codes suggestive of child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 35, 3–17. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorr LB, & Marchand V (2007). Pathway to the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, Peta I, McPherson K, & Greene A (2010). Fourth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect (NIS-4). Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman A (2009). Safety net effective at fighting poverty but has weakened for the very poorest. Washington, DC: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; Retrieved from: http://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=2859. [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Boyce WT, & McEwen BS (2009). Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: Building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. Journal of the American Medical Association, 301 10.1001/jama.2009.7542252-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tungate SL (2008). Welfare and child welfare collaboration. Dissertation abstracts international section a: humanities and social sciences. 70(2-A). Dissertation abstracts international section a: humanities and social sciences (pp. 706–). Ann Arbor, MI: ProQuest Information & Learning. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau (2004). Child maltreatment 2002. Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/resource/child-maltreatment-2002.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau (2005). Child Maltreatment 2003. Retrieved fromhttp://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/resource/child-maltreatment-2003.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau (2006). Child maltreatment 2004. Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/resource/child-maltreatment-2004.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau (2007). Child maltreatment 2005. Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/pubs/cm05/cm05.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau (2008). Child maltreatment 2006. Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/pubs/cm06/cm06.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau (2009). Child maltreatment 2007. Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/pubs/cm07/cm07.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau (Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau, 2010a). Child maltreatment 2008 Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/pubs/cm08/cm08.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau (Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau, 2010b). Child maltreatment 2009 Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/resource/child-maltreatment-2009.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau (2011). Child Maltreatment 2010. Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/resource/child-maltreatment-2010.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau (2012). Child maltreatment 2011. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/resource/child-maltreatment-2011.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau (2013). Child maltreatment 2012. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/resource/child-maltreatment-2012.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau (2014). Child maltreatment 2013. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/resource/child-maltreatment-2013.

- Woodland RH, & Hutton MS (2012). Evaluating organizational collaborations: Suggested entry points and strategies. American Journal of Evaluation, 33, 366–383. 10.1177/1098214012440028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge J (2010). Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data, Second Edition Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]