Abstract

This cohort study assesses the association of inflammatory symptoms with the progression of hair loss in women with frontal fibrosing alopecia.

Frontal fibrosing alopecia (FFA) is a cicatricial alopecia that results in hair follicle destruction on the frontotemporal hairline. To our knowledge, the association of inflammation with progression of the disease has not been studied prospectively.

Methods

We conducted this prospective cohort study between January 2016 and June 2019. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Hospital Ramón y Cajal. Verbal informed consent was obtained from each participant. Patient inclusion criteria were an age of 18 years or older and fulfillment of the diagnostic criteria of FFA.1 All patients started treatment with oral dutasteride (0.5 mg 3 times weekly), topical clobetasol (twice weekly), and triamcinolone injections (4-8 mg/mL every 6 months). Every patient was assessed with the Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia Severity Score (FFASS) during every 6-month visit.2 To improve the accuracy of the inflammation score, perifollicular scaling and erythema were evaluated by trichoscopy (grade 2, trichoscopic and clinical inflammatory signs present; grade 1, inflammatory signs not clinically evident, but present in trichoscopy; grade 0, absence of inflammatory signs). We considered that there was no progression of alopecia when there was not any increase in the FFASS extent score and that inflammation was controlled when the mean FFASS inflammation score remained less than 1. Exclusion criteria were changes in the initial treatment, a follow-up for less than 12 months, and coexistence of other hair loss conditions. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study participants and the FFASS scores. A t test was used to compare continuous variables. A 2-sided P value <.05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis was performed with SPSS statistical software version 15.0 (IBM Corp).

Results

A total of 62 patients were candidates to participate in the study, and 57 patients completed follow-up and were included in the analysis. All participants were women, and the mean (SD) age was 62.4 (10.4) years. A total of 47 (82%) had reached menopause. Mean (range) follow-up was 45.3 (30-48) months. Mean FFASS score in the first visit was 13.2 (range, 2-23). Mean FFASS extent score was 12.0 (range, 2-20), and inflammation score was 1.2 (range, 0-3). A total of 34 patients (60%) maintained a stabilization of their hairline recession. Of these, 26 (77%) also had an improvement of inflammatory signs, but inflammation persisted in 8 patients (24%). In 23 patients (40.4%), the hairline continued to recede despite treatment. In this group of patients, inflammation persisted in 16 patients (70%), but 7 patients (30%) had no inflammatory signs or experienced improvement in inflammation (Figure). Differences in progression of hair loss between patients with persistent inflammation and no inflammation are presented in the Table.

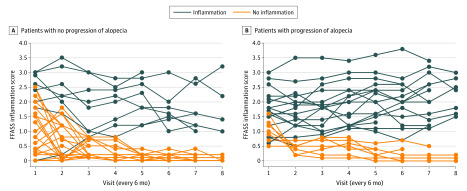

Figure. Grade of Inflammation According to the Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia Severity Score (FFASS).

Patients with no progression of alopecia (A) tended to have less inflammation than patients with progression of alopecia (B). However, we found patients with persistent inflammatory signs in both groups.

Table. Clinical Characteristics of Women With Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia (FFA) With and Without Persistent Inflammation During Follow-Up.

| Characteristic | FFA type | All patients with FFA (N=57) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With persistent inflammation (n=24) | Without persistent inflammation (n=33) | |||

| Age, mean (range), y | 63.6 (45-73) | 61.1 (42-70) | 62.4 (42-73) | .14 |

| Duration of the disease, mean (range), y | 6.7 (2-8) | 6.6 (2-9) | 6.6 (2-9) | .34 |

| Onset before menopause, No. (%) | 6 (25) | 4 (12) | 10 (18) | >.05 |

| FFASS at first visit, mean (range) | ||||

| Extent | 12.0 (2-20) | 12.5 (2-18) | 12.0 (2-20) | .24 |

| Inflammation | 1.9 (0-3) | 1.0 (0-2.5) | 1.2 (0-3) | .74 |

| Total | 13.9 (2-23) | 13.5 (2-20.5) | 13.2 (2-23) | .33 |

| Pruritus, No. (%) | 24 (100) | 30 (91) | 54 (95) | >.05 |

| Trichodynia, No. (%) | 8 (33) | 12 (36) | 20 (35) | >.05 |

| Eyebrow loss, No. (%) | 18 (75) | 25 (76) | 43 (75) | >.05 |

| Rosacea, No. (%) | 19 (79) | 5 (15) | 24 (42) | >.05 |

Abbreviation: FFASS, Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia Severity Score.

Discussion

The presence of a follicular lichenoid infiltrate was described in the first report of FFA in 1997.3 It is likely that a collapse of the immune privilege of the hair follicle induces its formation.4 The use of local corticosteroids has also been related to an improvement of erythema and peripilar casts.5 This is the most common scenario, as we observed that many patients with receding hairline had persistent inflammatory signs.

However, it is a fairly frequent occurrence in clinical practice to find patients with FFA who have no progression of their alopecia and persistent inflammatory signs; this has been noted in a large case series.6 The present study confirms this observation and establishes that 1 of 4 patients undergoing treatment presents with this situation. Furthemore, in some patients, hair loss progresses without inflammatory signs. This suggests that inflammatory infiltrates restricted to the isthmus are not visible at the skin surface.

The reasons for this discrepancy have yet to be determined. The biological processes between inflammation and the final destruction of the hair follicle comprise different steps that might be controlled with medical therapies. Thus, the presence of inflammatory infiltrate would not lead to formation of fibrosis if there is a concomitant medical treatment.

Limitations of this study must be noted. All of the included patients were women undergoing medical treatment. Nevertheless, every patient received the same therapeutic treatment, and data from real clinical practice are relevant in understanding the evolution of the disease. In addition, we cannot conclude a clear association of inflammation with progression of the disease, because the most definitive way to assess inflammation is biopsy.

In conclusion, the detection of inflammatory signs in FFA has an association with the progression of alopecia, but there is a noteworthy group of patients who show a discordance between inflammatory signs and progression of hair loss. The FFASS allows us to assess the efficacy of medical treatment for stopping clinical inflammation, but this is not necessarily associated with halting the progression of the alopecia.

References

- 1.Vañó-Galván S, Saceda-Corralo D, Moreno-Arrones ÓM, Camacho-Martinez FM. Updated diagnostic criteria for frontal fibrosing alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(1):e21-e22. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saceda-Corralo D, Moreno-Arrones ÓM, Fonda-Pascual P, et al. Development and validation of the Frontal Fibrosing Alopecia Severity Score. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(3):522-529. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.09.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kossard S, Lee MS, Wilkinson B. Postmenopausal frontal fibrosing alopecia: a frontal variant of lichen planopilaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(1):59-66. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(97)70326-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harries MJ, Meyer KC, Chaudhry IH, Griffiths CEM, Paus R. Does collapse of immune privilege in the hair-follicle bulge play a role in the pathogenesis of primary cicatricial alopecia? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35(6):637-644. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03692.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tosti A, ed. Dermoscopy of the Hair and Nails. 2nd ed Apple Academic Press Inc; 2015. doi: 10.1201/b18594 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacDonald A, Clark C, Holmes S. Frontal fibrosing alopecia: a review of 60 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(5):955-961. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.12.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]