Abstract

This secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial assesses the association of specialty team-based services for first-episode psychosis with criminal justice outcomes compared with usual treatment.

New-onset psychotic disorders can increase entanglements with the criminal justice system.1 The resulting convictions and incarcerations can increase risk of suicide, delay access to care, and irrevocably impair employment and other opportunities for already vulnerable young adults.1 Specialty team-based services for first-episode psychosis (FES) are effective across a range of outcomes,2 but little is known about their effect on criminality.3 We report a secondary analysis of a pragmatic randomized clinical trial of an FES (Specialized Treatment Early in Psychosis [STEP]) vs usual treatment (UT) for criminal justice outcomes.4

Methods

All participants in the original study4 gave written informed consent for review of judicial data, and the study was approved by the Yale Human Investigations Committee. The original trial protocol can be found in Supplement 1. The original trial followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guideline. Randomized treatment allocation occurred between April 2006 and April 2012 (eFigure in Supplement 2), and publicly available databases (Connecticut Judicial Branch and Criminal/Motor Vehicle Convictions) were queried through December 31, 2016, allowing extended follow-up before enrollment (median [range] follow-up, 4.2 [1.0-23.4] years) and after enrollment (median [range] follow-up, 6.6 [4.8-10.6] years). Data on juvenile (younger than 18 years) and out-of-state convictions were unavailable. Number of criminal convictions, crime description, category, type of sentence (jail vs probation), and offense dates were retrieved for each participant. Judicial categories reflect seriousness: infractions designate petty crimes or rule violations, felonies typically lead to jail sentences of 1 year or greater, and misdemeanors fall between these. We added the category of violent crime for offenses involving physical contact. Data were analyzed from January 2017 to November 2019.

Logistic regression with Wald test was used to evaluate differences in 16 conviction profiles after enrollment by randomization group, with adjustment for prior convictions. Time to first crime after enrollment by group was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method with log-rank test. Statistical significance was set at a 2-sided P value less than .05. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Of the 117 included patients with recent-onset psychosis (median [interquartile range] duration of untreated psychosis, 3 [0-72] months), 95 (81.2%) were male, and the mean (SD) age was 22.7 (5.1) years. Patients allocated to STEP vs UT did not differ by age, sex, race/ethnicity, duration of untreated psychosis,4 or prior convictions (Table). A minority (14 [12.0%]) had convictions prior to allocation.

Table. Criminal Justice Involvement in a First-Episode Psychosis Sample.

| Conviction | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STEP (n = 60) | Usual treatment (n = 57) | |||

| Before enrollment | After enrollment | Before enrollment | After enrollment | |

| Any offense | 6 (10) | 3 (5) | 8 (14) | 11 (19) |

| Felony | 3 (5) | 1 (2) | 4 (7) | 4 (7) |

| Misdemeanor | 2 (3) | 2 (3) | 7 (12) | 9 (16) |

| Motor vehicle | 2 (3) | 0 | 1 (2) | 4 (7) |

| Violation of probation | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Violent crime | 2 (3) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 4 (7) |

| Sentenced to jail | 5 (8) | 3 (5) | 8 (14) | 10 (18) |

| Probation | 3 (5) | 3 (5) | 5 (9) | 8 (14) |

Abbreviation: STEP, Specialized Treatment Early in Psychosis.

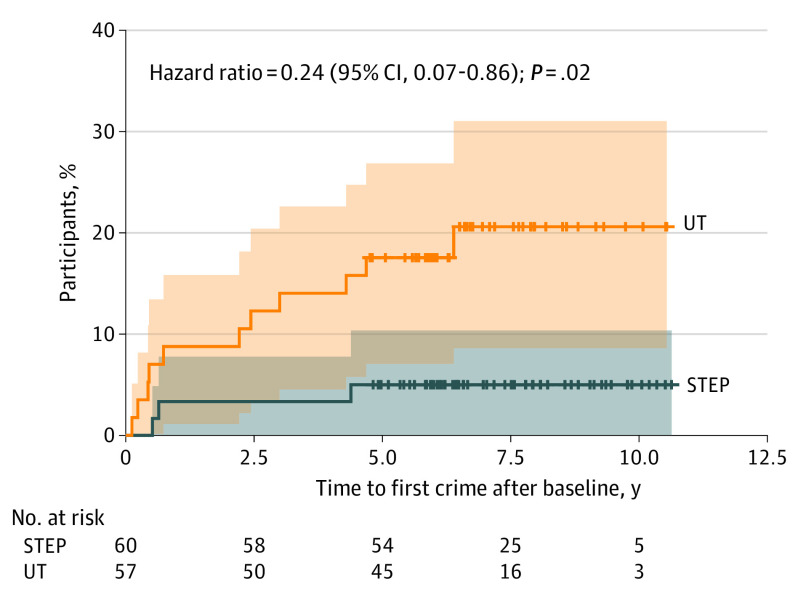

The overall number and seriousness of offenses was reassuringly low (Table). Only 13 of 85 total convictions (15%) were for violent offenses and 18 (21%) for felonies, with a predominance of misdemeanors (54 of 85 [64%]). After adjusting for prior convictions, patients allocated to STEP were significantly less likely to be convicted of any crime (odds ratio, 0.19; 95% CI, 0.04-0.85; P = .03) and nonsignificantly less likely to be sentenced to jail (odds ratio, 0.22; 95% CI, 0.05-1.01; P = .05). The number of new offenders was nonsignificantly lower in those assigned to STEP vs UT (1 of 60 [2%] vs 6 of 57 [11%]; P = .06). Notably, there was a 76% reduction in the risk of committing a first crime for those assigned to STEP vs UT (hazard ratio, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.07-0.86; P = .02) (Figure). Participants assigned to STEP also had a nonsignificantly lower 5-year first crime rate (5.00%; 95% CI, 0.51-10.51) compared with those assigned to UT (17.54%; 95% CI, 7.66-27.42). Participants convicted of at least 1 crime did not differ across STEP vs UT by age at enrollment, race/ethnicity, sex, or duration of untreated psychosis.

Figure. Time to First Crime After Enrollment in Specialized Treatment Early in Psychosis (STEP) vs Usual Treatment (UT).

Discussion

This analysis found that FES is associated with reduced criminality. The low overall prevalence of convictions in this sample was reassuring but limited detection of group differences. Nevertheless, allocation to STEP reduced subsequent and first-time convictions and was less than levels in a larger European trial.3 Putative mechanisms include STEP’s improvement of vocational functioning,4 which is associated with reduced youth criminality,5 and reduction of psychiatric hospitalizations,4 which disrupt work and school functioning but may also signal reductions in episodes of behavioral dysregulation that can result in arrests.6 However, these speculations need to be tested against more granular information about the circumstances of each arrest. Such replication with a larger sample and more comprehensive (eg, adding juvenile, jail diversion, and department of corrections data) databases is urgently needed to inform service design and policy.

Trial protocol.

eFigure. CONSORT flowchart.

References

- 1.Ford E. First-episode psychosis in the criminal justice system: identifying a critical intercept for early intervention. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015;23(3):167-175. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Correll CU, Galling B, Pawar A, et al. Comparison of early intervention services vs treatment as usual for early-phase psychosis: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(6):555-565. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stevens H, Agerbo E, Dean K, Mortensen PB, Nordentoft M. Reduction of crime in first-onset psychosis: a secondary analysis of the OPUS randomized trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(5):e439-e444. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srihari VH, Tek C, Kucukgoncu S, et al. First-episode services for psychotic disorders in the US public sector: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(7):705-712. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heller SB. Summer jobs reduce violence among disadvantaged youth. Science. 2014;346(6214):1219-1223. doi: 10.1126/science.1257809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wasser T, Pollard J, Fisk D, Srihari V. First-episode psychosis and the criminal justice system: using a sequential intercept framework to highlight risks and opportunities. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(10):994-996. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201700313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol.

eFigure. CONSORT flowchart.