Abstract

While uncommon, exertional-induced rhabdomyolysis is an important diagnostic consideration when encountering hyperintensity within one or more muscles on fluid sensitive sequences in conjunction with signal abnormality in the overlying superficial fascia and subcutaneous fat. The clinical history of recent extreme exercise helps distinguish this disorder from other possible diagnoses, such as cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis, compartment syndrome, inflammatory processes and diabetic myonecrosis. Patients diagnosed with severe exertional induced rhabdomyolysis often require hospital admission for intravenous hydration and serial laboratory monitoring due to the potential risk of acute renal failure. While contributory, magnetic resonance imaging findings can be nonspecific, and therefore the clinical history is often essential in making this diagnosis.

Keywords: Exertional rhabdomyolysis, MR imaging

Introduction

Rhabdomyolysis is a severe type of acute muscle injury characterized by the rapid destruction of muscle, leading to the release of intracellular contents into the blood [1,2]. One potential etiology includes excessive physical activity, or exertional rhabdomyolysis (ER), which is clinically characterized by acute, severe pain due to muscle breakdown temporally-associated with strenuous exercise or normal exercise under extreme circumstances. In our report of 4 cases we encountered 1 female patient and 3 male patients with ages ranging from 17 to 33, all of which who presented with at least 2 days of upper extremity pain following isolated upper extremity exercise, and were found to have elevated serum creatine kinase (CK) levels. All 4 patient underwent an upper extremity MR examination demonstrating nonspecific intramuscular hyperintensity on T2-weighted images with varying degrees of fascial and subcutaneous edema, without appreciable fluid collection or intramuscular signal abnormality on T1-weighted images. Conservative therapy in these patients resulted in clinical and laboratory improvement with subsequent discharge in stable condition. Our report of 4 cases of this disorder in the upper extremity reviews the pertinent MR imaging findings, which can be nonspecific; whereby the clinical history of recent extreme exercise, can suggest the diagnosis. Due to the rising popularity of extreme exercise programs, the incidence of this entity may increase, and familiarity with typical imaging findings is necessary for radiologists to suggest this diagnosis.

Case reports

Case 1

Patient 1 is a 25-year-old male who presented with a history of 2 days of right upper extremity pain; a delayed onset following heavy weightlifting training. Physical examination revealed marked tenderness to palpation of the right shoulder and upper scapular regions. The patient was subsequently hospitalized due to the severity of pain and an elevation of serum CK levels; the peak CK level during admission was 29,642 U/L (normal range, 30-220 U/L).

MR imaging of the right shoulder was performed 4 days after admission (approximately 6 days after symptom onset), and revealed hyperintensity throughout the supraspinatus muscle belly on fat suppressed T2-weighted images, as well as subcutaneous edema and signal abnormality along the superficial fascial plane (Fig. 1). There was no appreciable fluid collection, deep fascial signal abnormality, or intramuscular signal abnormality on T1-weighted images.

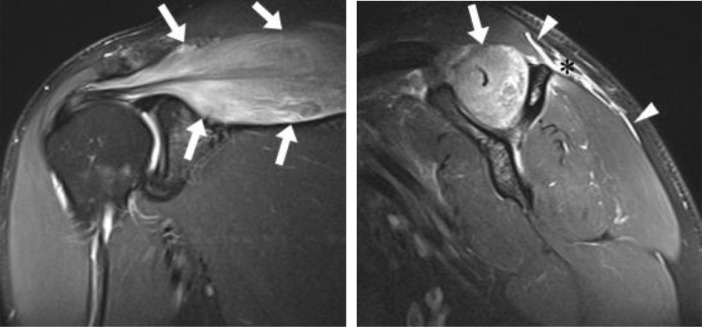

Fig. 1.

Twenty-five years old man with 2 days of right upper extremity pain following heavy weight lifting. Coronal (a) and sagittal (b) fat-suppressed T2-weighted images demonstrate hyperintensity in the supraspinatus muscle (white arrows), superficial fascial signal abnormality (white arrowheads), and subcutaneous edema (black asterisk).

Patient 1 received a clinical diagnosis of ER secondary to the elevated serum CK values, recent history of extreme exercise, and MR imaging findings. Management included intravenous fluids, analgesic agents, and serial laboratory monitoring of CK values and renal function. Patient 1 was subsequently discharged in stable condition once the CK values began to normalize.

Case 2

Patient 2 is a 33-year-old female who presented to the emergency department following 2 days of left upper extremity swelling, decreased range of motion and a reduction of strength after resistance training. The patient had completed kettlebell exercises and push-ups approximately 2 days prior to presenting to the emergency department. The patient's medical history was significant for hypothyroidism managed with levothyroxine. Physical examination revealed left upper extremity swelling with tenderness to palpation over the biceps and brachioradialis musculature, as well as a decreased range of motion at the left elbow. Laboratory analysis demonstrated a peak serum CK of 18,479 U/L.

On the day of presentation (2 days after symptom onset), the patient underwent MR imaging of her left elbow demonstrating abnormally increased signal intensity within the brachialis, brachioradialis, and extensor carpi radialis longus muscles and minimally in the lateral head of the triceps muscle on fat suppressed T2-weighted images. There was moderate superficial fascial signal abnormality, minimal deep fascial signal abnormality, and moderate to severe subcutaneous edema, (Fig. 2) however no discrete fluid collection or intramuscular signal abnormality of T1-weighted images.

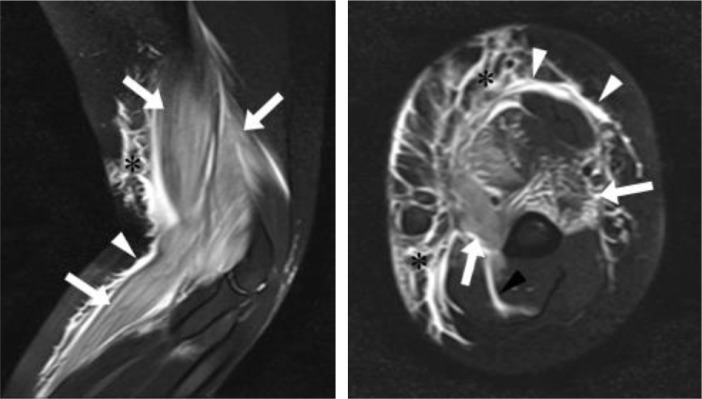

Fig. 2.

Thirty-three years old woman with 2 days of left upper extremity swelling and difficulty moving after partaking in weight lifting with kettlebell exercises and push-ups approximately 2 days prior to presentation. Sagittal (a) and axial (b) fat-suppressed T2-weighted images demonstrate hyperintensity in the brachialis, brachioradialis, extensor carpi radialis longus, and lateral head of the triceps muscles (white arrows), superficial fascial signal abnormality (white arrowheads), deep fascial signal abnormality (black arrowheads), and subcutaneous edema (black asterisks).

Patient 2 subsequently received a clinical diagnosis of ER secondary to the recent history of extreme exercise, elevated serum CK values, and supportive MR imaging findings. Conservative management included intravenous fluids, analgesic agents, and serial laboratory monitoring of CK values and renal function. Ultimately patient 2 was discharged in stable condition once the CK values began to normalize.

Case 3

Patient 3 is a 17-year-old male who presented to the emergency department with a 5-6 days history of right upper extremity swelling after performing biceps curls. On physical examination the right upper extremity appeared swollen from the shoulder to the hand with compressible soft tissues. Laboratory analysis yielded an elevated serum CK of 19,326 U/L. The patient was admitted to the hospital.

The patent underwent MR imaging of the right upper extremity on the day of admission, which was remarkable for abnormal increased signal intensity throughout the biceps and brachialis muscles on fluid-sensitive inversion recovery sequences. Severe subcutaneous signal abnormality/edema-like signal, moderate/severe superficial fascial signal abnormality and minimal deep fascial signal abnormality were also present (Fig. 3). Again, there was no appreciable fluid collection or intramuscular signal abnormality on T1-weighted images.

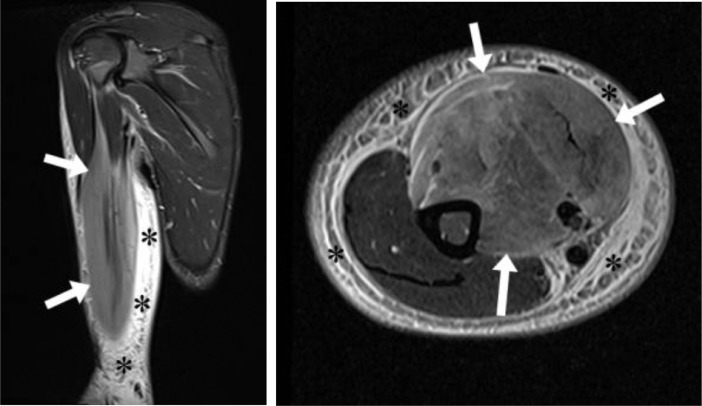

Fig. 3.

Seventeen years old boy with 5-6 days of right upper extremity swelling after performing biceps curls. Coronal (a) and axial (b) inversion recovery images demonstrate hyperintensity in the biceps and brachialis muscles (white arrows) and subcutaneous edema (black asterisks).

A clinical diagnosis of ER was made for patient 3, secondary to recent history of extreme exercise, the elevated serum CK values, and MR imaging findings. Patient 3 was treated with conservative management including intravenous fluids and analgesic agents, while monitoring serial laboratory tests including CK values and renal function. Once the CK values began to normalize the patient was discharged in stable condition.

Case 4

Patient 4 is a 23-year-old male who presented to the emergency department with a 1 day history of left upper extremity swelling, dyspnea, and chest tightness after resistance training and playing golf. On exam, swelling of the left upper extremity was noted, and the limb appeared grossly enlarged in comparison to the contralateral side. The peak serum CK value was 2732 U/L, and the patient was admitted.

The patient underwent MR imaging of the left upper extremity 3 days after presentation revealing abnormally increased signal intensity throughout the long head of the triceps muscle and minimally involving in the teres major muscle on fluid-sensitive inversion recovery sequences. Moderate superficial fascial signal abnormality, minimal deep fascial signal abnormality, and moderate subcutaneous edema were also appreciated (Fig. 4). There was no abnormal intramuscular signal on T1-weighted images and no appreciable fluid collections were present.

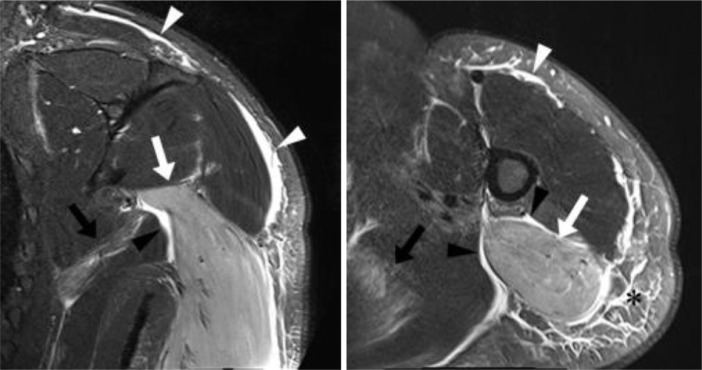

Fig. 4.

Twenty-three years old man with 1 day history of left upper extremity swelling, dyspnea, and chest tightness following recent weight lifting and golf. Coronal (a) and axial (b) inversion recovery images demonstrate hyperintensity in the long head of the triceps muscle (white arrows) and to a lesser extent teres major muscle (black arrows), superficial fascial signal abnormality (white arrowheads), deep fascial signal abnormality (black arrowheads), and subcutaneous edema (black asterisks).

Patient 4 received a clinical diagnosis of ER secondary to the elevated serum CK values, recent history of extreme exercise, and ancillary MR imaging findings. Management included intravenous fluids and analgesic agents, with serial monitoring of laboratory test including CK levels and renal function. Once the CK values began to normalize patient 4 was subsequently discharged in stable condition.

Discussion

ER, a potentially life-threatening condition with an incidence of approximately 29.9 per 100,000 patient years [4], is due to damage of the sarcolemma (cell membrane of striated muscle), leading to muscle necrosis and the release of intracellular contents including potassium, phosphate, myoglobin, CK, and urate [3]. Histologically, this release can precipitate microvascular damage, capillary leak and increased intracompartmental pressures, as well as reduce tissue perfusion and induce ischemia [3]. Overproduction of heat, often associated with ER, yields increased intracellular calcium via depletion of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). The loss of ATP causes dysfunction of Na/K–ATPase and Ca2+ATPase pumps, leading to this intracellular increase and subsequent activation of proteases and production of reactive oxygen species, eventually culminating in the death of skeletal muscle cells [4].

Potential etiologies of rhabdomyolysis includes both congenital and acquired causes. Enzymatic defects of carbohydrate metabolism, mitochondrial lipid metabolism and other disorders such as malignant hyperthermia, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and idiopathic rhabdomyolysis and myoadenylate deaminase deficiency are examples of congenital causes. Acquired causes include exposure to specific medications and illicit substances (such as heroin, morphine, methadone, statins, and alcohol), direct muscle injury (crushing, freezing, burning), ischemic injury (compression, vascular occlusion), excessive or prolonged exercise, convulsions, metabolic disorders (diabetic ketoacidosis, hypothyroidism), infection, heat stroke, and inflammatory myopathies [3].

The clinical manifestations of ER are broad and nonspecific, posing challenges with diagnosis in the early phase [3]. Local symptoms and signs of rhabdomyolysis can include pain, weakness, tenderness, and swelling of the specific muscles involved. Patients may also present with malaise, fever, tachycardia, nausea, vomiting, tea-colored urine, confusion, agitation, delirium or anuria [3]. Myoglobinuria can be an important manifestation of the condition, but rapid clearance of myoglobin from the urine makes it a less sensitive indicator for ER [3]. In comparison, a markedly elevated serum CK is a reliable and sensitive indicator of muscle injury [4].

The early complications of rhabdomyolysis can include hyperkalemia, hypocalcemia, hepatic inflammation, cardiac arrhythmia and cardiac arrest (due to hyperkalemia) [3]. The late complications can include acute kidney failure and/or disseminated intravascular coagulation [3]. Compartment syndrome due to muscle swelling can occur at any time during the course of this disease with the potential to compress nervous and/or vascular structures within the affected compartment [3].

Imaging findings are nonspecific with MRI yielding increased sensitivity when compared to CT or ultrasound. The affected muscle tissue typically demonstrates increased signal intensity on fluid-sensitive sequences. In the acute phase of the disease, an increased diameter of the involved muscle can also be appreciated. Gradient echo imaging may be helpful in the late phase of the disease to distinguish hemosiderin, which is seen in hemorrhagic transformation [3].

Clinical improvement and reductions in serum CK levels coincide with a decrease in the degree of signal abnormality within the affected muscle, though abnormal signal within the muscles may persist longer than abnormal laboratory values [3]. Treatment involves complete rest to the affected muscle and maintenance of adequate hydration [4]. In the setting of compartment syndrome, fasciotomy may be used to decompress the involved compartment [3].

In our 4 cases, patients generally presented for medical evaluation with localized pain and/or swelling approximately 1-2 days following physical exertion. On noncontrast MR imaging, varying degrees of hyperintensity were seen within the affected muscle or muscles on fluid-sensitive sequences, with normal intramuscular signal intensity on the T1-weighted images. Signal abnormality in the subcutaneous soft tissue and superficial fascia was present on fluid sensitive sequences in all patients, and deep intermuscular fascial signal abnormality was present in 3 of the 4 patients. None of the patients’ imaging studies revealed regional fluid collections. Clinically, each patient reported a history of extreme exercise prior to symptom onset and elevated serum CK values discovered during evaluation. All subjects were treated with intravenous fluids and were given symptomatic treatment for pain. None of the patients experienced renal failure during hospital admission. For each patient, clinical symptoms and serum CK levels improved during hospitalization.

While other pathologic processes can be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with these imaging findings, differentiation can usually be made based on clinical history and imaging features. Differential considerations based on imaging findings include but are not limited to infectious and inflammatory conditions such as; cellulitis, necrotizing fasciitis, compartment syndrome, inflammatory processes, and diabetic myonecrosis [2].

Cellulitis is an infectious process usually localized to the dermis and subcutaneous fat [2]. It is a painful soft tissue infection displaying dermal thickening, erythema, and swelling. Patients will typically present with fever. MR imaging displays irregular dermal and soft tissue thickening with heterogeneous hyperintensity on fluid-sensitive sequences throughout the effected superficial soft tissues and variable contrast enhancement of the affected area [2,6]. As opposed to intramuscular signal abnormality on fluid-sensitive sequences present in ER, in the setting of cellulitis intramuscular signal abnormality is less likely in the absence of deep soft tissue extension. MRI is typically not required for the diagnosis of cellulitis, however, it can be utilized for an atypical presentation, such as; suspected abscess, neoplastic disorder, or a rapidly progressive nature [2].

Necrotizing fasciitis is a rapidly progressing deep fascial soft tissue infection. A specific sign of necrotizing fasciitis is gas located in the subcutaneous and deeper soft tissues caused by gas-forming anaerobic organisms [2]. Infected deep and intermuscular fascia demonstrates increased signal intensity on both sides of the fascia on fluid-sensitive sequences, representing purulent perifascial edema and fluid [2]. On post contrast images, the involved fascia will enhance in the early stages and show non enhancement as necrosis progresses [2]. Occasionally, peripherally enhancing fluid collections can be seen; which is an indicator of a less fulminant process [2,6]. Given the overlap of imaging findings in ER and necrotizing fasciitis the clinical scenario is critical to differentiate between these entities.

When considering the diagnosis of compartment syndrome there is a similar overlap of imaging manifestations present in the setting of ER. Compartment syndrome is caused by prolonged increased intramuscular pressure within a single fascial compartment [2]. Increased intramuscular pressures greater than 15-20 mm Hg decrease capillary perfusion and inhibit lymphatic flow creating ischemic changes to the muscle [2]. Imaging characteristics include decreased signal intensity on T1-weighted sequences and increased signal intensity on fluid-sensitive sequences within the affected muscles, most commonly the anterior and lateral compartments of the lower leg [2]. Affected muscles demonstrate loss of normal muscles striations and enlargement, and findings may progress to muscle necrosis, with more heterogeneous intramuscular signal abnormality. Contrast enhancement is variable [5,6].

Inflammatory processes such as dermatomyositis can also demonstrate imaging findings similar to that of ER. Dermatomyositis can show symmetrical bilateral diffuse subcutaneous, perimuscular and intramuscular hyperintensity on fluid sensitive sequences. In acute myositis heterogeneous intramuscular enhancement can be seen. Fatty replacement and muscle atrophy will appear hyperintense on T1-weighted images, indicating chronic dermatomyositis. Calcification can be seen and may be seen as sheetlike regions of hypointensity on T1- and T2-weighted images [6].

Diabetic myonecrosis is seen in patients with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus [2]. Patients exhibit acute pain in the absence of precipitating trauma or palpable mass with imaging often revealing diffuse subcutaneous edema, perifascial fluid, marked muscle swelling, diffuse muscle contrast enhancement and occasionally, foci of rim-enhancement suggesting myonecrosis. Again, apart from the rim-enhancing foci, the imaging findings in the acute phase of diabetic myonecrosis is similar to that of ER. The chronic phase is suspected when the muscles are atrophic and the prior hyperintensity on T2-weighted images is lost [6].

Conclusion

In summary, ER is an important consideration when abnormal hyperintensity within muscle(s), subcutaneous soft tissues, and superficial as well as deep fascial layers on fluid sensitive sequences are encountered on MR imaging. Given the nonspecific MR imaging findings on fluid-sensitive sequences correlation with presenting symptoms, clinical history, and laboratory values is critical when considering a focused differential diagnosis. Early suggestion of ER as a diagnosis is imperative to avoid potentially significant renal complications.

Ethical approvals

All components of study involving human participants were performed with IRB approval, waiver of informed consent and in accordance with our institutional ethical standards.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interests: The authors declare that there were no conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Scalco RS, Snoeck M, Quinlivan R. Exertional rhabdomyolysis: physiological response or manifestation of an underlying myopathy? BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2016;2 doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2016-000151. doi:10.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu JS, Habib P. MR imaging of urgent inflammatory and infectious conditions affecting the soft tissues of the musculoskeletal system. Emerg Radiol. 2009;16:267–276. doi: 10.1007/s10140-008-0786-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moratalla MB, Braun P, Fornaas GM. Importance of MRI diagnosis and treatment of rhabdomyolysis. Eur J Radiol. 2008;65:311–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tietze D, Borchers J. Exertional rhabdomyolysis in the athlete: a clinical review. Sports Health. 2014;6(4):336–339. doi: 10.1177/1941738114523544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yilmaz TF, Toprak H, Kilsel K. MRI findings in crural compartment syndrome: a case series. Emerg Radiol. 2014;21:93–97. doi: 10.1007/s10140-013-1156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaudhry AA, Baker KS, Gould ES, Gupta R. Necrotizing fasciitis and its mimics: what radiologists need to know. AJR. 2015;204:128–139. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.12676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]