Abstract

Natural rubber (NR) nanocomposites were prepared by filling cornmeal graphene (CGE) to improve its mechanical properties and thermal properties, and CGE was modified with coupling agents to improve its dispersion in NR. The mechanical properties, wear resistance, thermal stability, and morphology of CGE/NR nanocomposites were studied. The results showed that when NR was 100 phr (parts per hundred rubbers), the CGE was 0.02 phr, and the coupling agent KH590 was 2 phr, the thermal stability and mechanical properties of the CGE/NR nanocomposites were the best. Compared with NR, the thermal conductivity of the nanocomposites increased by 6.0 mW/g, and the decomposition temperature increased by 37 °C. The mechanical properties and wear resistance of KH590-CGE/NR nanocomposites were the best, and compared with NR, the tensile strength, elongation at break, and wear resistance of KH590-CGE/NR nanocomposites increased by 16, 14, and 17%, respectively. The compatibility and dispersion of KH590-CGE/NR nanocomposites were the best.

Introduction

With the development of the automobile industry, convenient transportation brings great revolution and, at the same time, also brings security problems, especially when the automobile tire is punctured on the highway, it is an urgent safety problem that is to be solved. Natural rubber (NR) is a natural carbohydrate composed of cis-1,4-polyisoprene and nonrubber substances such as protein,1,2 sugars, and ash,3,4 in which the unsaturated double bonds of NR are easily oxidized, leading to poor thermal stability.5−7 Thus, the automobile tire prepared by NR would cause heat when rubbed on the ground of the highway for a long time.8−10 When the heat cannot be conducted out, it accumulates inside the NR, causing heat aging of the NR and tire puncture.11 In industrial production, carbon black and silica were usually used to fill and reinforce NR,12 but the use of these two fillers would cause serious dust pollution,13 and there was almost no improvement in the thermal properties of NR. Currently, some researchers are trying to use graphene (GE) to reinforce NR.14 Graphene was composed of carbon atoms in multiple hexagonal lamellar structures.15 This structure of graphene can not only transfer heat16 but also export heat to prevent heat accumulation in NR,17,18 avoiding heat aging of NR.19 The traditional graphene was prepared with graphite, but it could not be used industrially due to its high cost.20 Recently, the researchers have successfully produced graphene from biological husks such as corn stalks and rice husks.21,22 Corn flour is a rich source of agricultural product, which has the advantages of wide sources, diverse varieties, cheap prices, short regeneration cycles, and no pollution to the environment, so we used self-made cornmeal graphene (CGE) to reduce costs of graphene in this work, and the CGE was modified with coupling agents to improve the mechanical and thermal properties of the NR nanocomposites.

Experimental Section

Materials

Natural rubber (NR) was obtained from Hainan Natural Rubber Industrial Group (China). Cornmeal graphene (CGE) was self-made from corn (the performance of CGE and commercial graphene was similar). Silica (SJ-Z 95, industrial grade) was supplied by Shandong Weifang Sanjia Chemical Co., Ltd. Sulfur (industrial grade) was supplied by China Brother Chemical Factory Group Corporation. Accelerator M (2-mercapto-benzothiazole, industrial grade) was purchased from Henan Kailun Chemical Co., Ltd. Silane coupling agents KH550 (3-triethoxysilyl-1-propylamine), KH590 (3-mercaptopropyl trimethoxysilane), and Si69 (bis-g-(triethoxysilane), analytical grade) were obtained from Nanjing Shuguang Chemical General Factory. Other additives were commercially available in the rubber industry.

Sample Preparation

The cornflour sample was taken out and placed in a beaker, and 1 mol/L phosphoric acid solution was added to it at a mass ratio of 1:3 (phosphoric acid/corn flour) with stirring. The sample was left for 24 h, filtered, and washed repeatedly with deionized water until the pH was neutral. The dried sample was put into a tube furnace (TNG1200-60, Shanghai Shinbae Industrial Co., Ltd., China) with nitrogen flow, and the temperature was increased to 900 °C for 90 min at a heating rate of 5 °C/min. Then, the dried sample was cooled to room temperature, and the sample was taken out and ground into powder. Moreover, nickel powder was added to the powdered sample and placed again in the tube furnace with nitrogen at 900 °C for 90 min. After removing the sample, the sample was added with 0.5 mol/L hydrochloric acid solution with stirring. The sample was repeatedly filtered with deionized water until the pH was 7, and then dried in an oven after standing for 12 h. Finally, the CGE was prepared by the Hummers method.23 The obtained CGE was graphene by X-ray diffraction (XRD) and Raman characterization,24,25 and the crystal surfaces were (002), (101), and (004), and 2θ = 26.5° by the XRD test; the height of the G peak and the 2D peak was roughly equal by the Raman test.

The CGE was placed in a beaker with distilled water at 60 °C under ultrasonication for 30 min, then filtered and dried. After that, the CGE was coated with a modifier KH550 (KH590 or Si69), stirred until a homogeneous dispersion, and dried to prepare modified CGE. The NR was kneaded on a double-roll mill manufactured (SK-160 B) by Shanghai Qicai Hydraulic Machinery Co., Ltd. at a roller temperature of 45 °C and a distance of 0.8 mm for 20 min. After that, the roll spacing was adjusted to 2 mm and added with carbon black, stearic acid, zinc oxide, accelerator M, sulfur, and modified CGE. They were mixed at a roller temperature of 55 °C for 30 min, in which the basic formula was 100 phr NR (parts per hundred rubbers, mass g), 5 phr carbon black, 3 phr zinc oxide, 2 phr accelerator M, 1 phr sulfur, 2 phr stearic acid, 1.5 phr antioxidant D, and 0.02 phr modified CGE. Finally, the mixtures were cured in an electrically heated hydraulic press (XLB-D350 × 350 × 2, Shanghai First Rubber Machinery) at 150 °C under a pressure of 10 MPa for 30 min. The preparation process of the sample is shown in Figure 1 (graphene was treated with the coupling agent KH590).

Figure 1.

Process of KH590-CGE/NR.

Characterization

Tensile strength was determined by an electronic universal testing machine (CSS-2200) produced by China Changchun Intelligent Instrument Equipment Co., Ltd. According to ISO37, Shore A hardness was measured by a rubber hardness tester (LX-A) produced by Shanghai Liuling Instrument Factory according to ISO 48. Wear attrition was determined using a rubber abrasion tester (GT-7012-D) produced by Gaotie Testing Instrument Co., Ltd. according to BS903A9. The thermal properties were studied using a Jiangsu Test Mechanical Ltd. (Jingdu) aging oven (401 B) at 200 °C for 24 h according to ISO188. For each of the measurements, with the average reported for at least five readings, the errors in the measurement of mechanical properties were within 10%.

The thermal stability of the sample in a nitrogen atmosphere was tested using a thermogravimetric (TG) analyzer (STA 449 F 3 Jupiter, German Netzsch Co., LTD.) from 20 to 600 °C at a heating rate of 5 °C/min. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was performed by a DSC instrument (204 F 1 UK Malvern Co., Ltd.) from 40 to 550 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min. The vulcanizate samples were fractured in liquid nitrogen, then the fracture surface was sputtered with gold, and the fracture morphologies of the samples were observed by scanning electron microscopy and elemental analysis (SEM, model S-4300, Hitachi Co., Japan). The infrared spectra of the samples were recorded using a Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer (model Spectrum 2000, PerkinElmer Co.). FTIR spectra were collected after 256 scans at 2 cm–1 resolution in the region of 4000–400 cm–1.

Results and Discussion

Effect of CGE Content on the Mechanical and Heat Resistance of CGE/NR Nanocomposites

The effects of the CGE content on the mechanical properties and heat aging properties of CGE/NR nanocomposites are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Effect of CGE content on (a) tensile strength, (b) elongation at break, and (c) Shore A hardness of CGE/NR nanocomposites.

The tensile strength and the Shore A hardness of the CGE/NR nanocomposites slowly increased with the addition of CGE before heat aging, and the elongation at break slowly decreased. When the CGE content was 0.02 phr, the mechanical properties of the CGE/NR nanocomposites showed the highest value after heat aging. Generally, the smaller the difference between the mechanical properties before and after aging is, the better the heat resistance of the materials. When the CGE content was 0.02 phr, the difference between the mechanical properties was the smallest, so the heat resistance of the CGE/NR nanocomposites was the best. It could be explained that the CGE could be adsorbed on the macromolecular chain of NR. When the CGE content increased, the adsorbed points increased, limiting the movement of the NR molecular chain before heat aging. If NR macromolecular chain orientation had to be made, a greater force was required, making the tensile strength and Shore A hardness increase. With the addition of CGE, the viscosity and flexibility of the nanocomposites slowly decreased, so its elongation at break gradually reduced. When the content of CGE as a nano-sized filler exceeded 0.02 phr, the CGE would agglomerate and difficultly disperse in the NR, making uneven local stress of the nanocomposites and the poor reinforced effect. Moreover, the behavior of the CGE hole changed from the original heat conduction to heat storage.26 The heat storage of CGE increased, and the heat could not be released. There was a heat difference in the samples’ local area so that the heat resistance of the nanocomposites was improved. Therefore, when the CGE content was 0.02 phr, the mechanical properties and heat resistance of the CGE/NR nanocomposites can be improved.

Effect of Coupling Agents on the Mechanical Properties of CGE/NR Nanocomposites

The mechanical properties of CGE-modified NR were not significantly increased as in Figure 2. The surface of CGE was treated with KH550, Si69, and KH590 coupling agents to modify NR. With the addition of the coupling agents, the tensile strength, elongation at break, and Shore hardness of the CGE/NR nanocomposites were higher than those without coupling agents before heat aging as in Figure 3, and the mechanical properties of KH590-CGE-modified NR nanocomposites were better than those of KH550-CGE/NR and Si69-CGE/NR nanocomposites. Compared with NR, the tensile strength, elongation at break, and Shore A hardness of KH590-CGE/NR nanocomposites increased by 16, 14, and 17%, respectively. The difference between the mechanical properties of KH590-CGE/NR nanocomposites before and after heat aging was the smallest in three coupling agent-modified NR nanocomposites, indicating that the thermal property was the best. This suggested that the CGE was an inorganic material, and NR was an organic polymer, and one end of the coupling agent and NR was connected by chemical bonding, and the other end of the coupling agent and CGE was connected by physical adsorption. KH590 (HS(CH2)3Si(OCH3)3) had less steric hindrance than Si69 ((H5C2O)3Si(CH2)3S4(CH2)3Si (H5C2O)3), and HS-group of KH590 was more suitable for modifying CGE/NR nanocomposites than the NH2 group of KH550 (NH2(CH2)3Si(OC2H5)3). HS and NR formed chemical cross-links, so the modified effects of KH590-CGE/NR was the best.

Figure 3.

Effect of the coupling agent on the (a) tensile strength, (b) elongation at break, and (c) Shore A hardness of CGE/NR nanocomposites.

Effect of Coupling Agents on the Wear Resistance of CGE/NR Nanocomposites

The wear resistances of NR, CGE/NR, KH550-CGE/NR, Si69-CGE/NR, and KH590-CGE/NR nanocomposites were 0.062, 0.060, 0.054, 0.054, and 0.052 mm3/m, respectively, in Table 1. The wear resistance of CGE/NR nanocomposites was less than that of NR, and the wear resistances of the coupling-agent-modified CGE/NR nanocomposites were smaller than those of CGE/NR nanocomposites, which meant that CGE and the coupling agent could improve the wear resistance of nanocomposites, especially KH590-CGE/NR nanocomposites was the best in wear resistance. This could also be explained with the mechanical properties of the adsorption theory. The NR and CGE cross-linked to form a denser network structure, where the friction generated improved the wear resistance of the nanocomposites.

Table 1. Effect of Coupling Agents on Wear.

| coupling agent | wear (mm3/m) |

|---|---|

| NR | 0.062 |

| CGE/NR | 0.060 |

| KH550-CGE/NR | 0.054 |

| Si69-CGE/NR | 0.054 |

| KH590-CGE/NR | 0.052 |

Effect of Coupling Agents on the Thermal Stability of CGE/NR Nanocomposites

The unsaturated NR, with poor thermal stability, is limited by its applications. There were two mass loss stages of CGE/NR nanocomposites in Figure 4a and the corresponding degradation peaks in the DTG curve in Figure 4b. The first mass loss occurred at about 150 °C, and a weak degradation peak appeared in the DTG curve, which suggested that small molecules such as stearic acid and coupling agents in the nanocomposites were volatilized or decomposed. Another mass loss appeared at about 350 °C, and the TG curves were close to flat at about 475 °C; there was a main degradation peak in the DTG curve. It could be explained that the molecular chain of the NR was decomposed (at 243 °C), followed by Si69-CGE/NR, KH550-CGE/NR, and finally KH590-CGE/NR nanocomposites. The second decomposition temperature of the KH590-CGE/NR nanocomposites was 280 °C, which was 37 °C higher than that of NR. It was considered that the free radical of Si69 could make NR decompose earlier and easily combined. The coupling agent KH550 did not improve the thermal stability of NR. KH590 could improve the thermal stability of NR due to its small steric hindrance and cross-linking with NR, limiting the movement of NR.

Figure 4.

TG (a) and DTG (b) curves of NR and CGE/NR nanocomposites.

As most rubber products are used at around 150 °C, the thermal stability of rubber at this temperature is extremely important. The decomposition of KH550-CGE/NR, Si69-CGE/NR, and KH590-CGE/NR nanocomposites was earlier than that of NR due to the volatilization of the coupling agent in the nanocomposites. If the used temperature of nanocomposites was about 150 °C, the CGE/NR nanocomposites could be used directly. NR will undergo temperature changes during the degradation process, and endothermic or exothermic phenomena may occur. Due to the structure and excellent thermal conductivity of CGE,27,28 the addition of CGE would improve the thermal properties of the CGE/NR nanocomposites. The curves first showed a downward trend from 0 to 300 °C as in Figure 5a, which meant that the samples were in the exothermic process. When the temperature exceeded 300 °C, it was in the degrading and endothermic process, and the mass loss stage of TG curves corresponded to the main degradation peak of DTG curves. The KH590-CGE/NR nanocomposites showed the largest heat change, their heat flow rate increased from −9.9 to −3.9 mW/g, and their thermal conductivity increased by 6.0 mW/g.

Figure 5.

(a) High-temperature and (b) low-temperature DSC curves of NR and CGE/NR nanocomposites.

The heat change of NR was the smallest in the same temperature stage, and its heat flow rate was increased from −40.1 to −38.8 mW/g. This indicated that the addition of CGE could fully exert thermal conductivity, which improved the thermal conductivity and thermal stability of the nanocomposites.

In the low-temperature region, the first glass transition temperature (Tg) was −61.8 °C of KH590-CGE/NR nanocomposites in Figure 5b, followed by CGE/NR nanocomposites, and finally NR (−63.2 °C), which suggested that the low-temperature resistance of NR was better than those of CGE/NR and KH590-CGE/NR nanocomposites, while the Tgs of the latter two were higher than that of NR, and the Tg of KH590-CGE/NR nanocomposites was the highest, which meant that the low-temperature resistance of the CGE-modified NR nanocomposites was weaker. It could be explained that the low-temperature resistance of NR was determined by the double bonds and side groups in the macromolecular chain. The addition of a coupling agent would make NR cross-link with the coupling agent and CGE adsorb on the coupling agent, changed the double bond structure of the NR molecular chain and increased the polar side group, forming some intramolecular hydrogen bonds, making the flexibility decrease and Tg increase. In summary, the KH590-CGE/NR nanocomposites were suitable for high-temperature resistance, followed by KH550-CGE/NR and Si69-CGE/NR, respectively. CGE/NR nanocomposites are suitable for room temperature (about 150 °C), and NR is suitable to be used in a low-temperature environment.

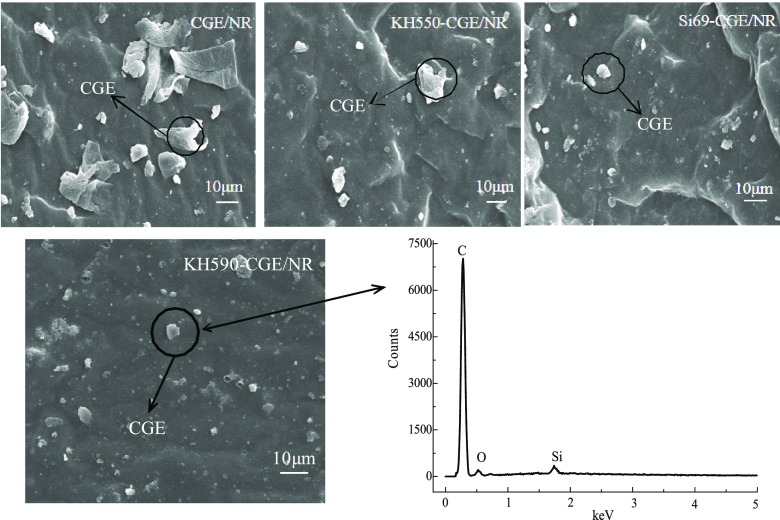

Microscopic Morphology and Structure of CGE/NR Nanocomposites

The SEM images of the CGE/NR nanocomposites and the EDS image of KH590/CGE/NR nanocomposites are presented in Figure 6. The CGE was not well dispersed in the NR without a coupling agent, and some CGEs were agglomerated. After the addition of the coupling agent, the dispersion of CGE in the NR was improved. Compared with the CGE/NR nanocomposites, a small amount of agglomeration occurred upon adding KH550 and Si69, and there was no agglomeration of CGE with KH590. The EDS image of KH590/CGE/NR nanocomposites showed that the elemental composition of these big spots was the C element of CGE, and it can be seen that the CGE treated with KH590 was dispersed well in the NR.

Figure 6.

SEM images of CGE/NR nanocomposites with the coupling agent and EDS image of KH590/CGE/NR nanocomposites.

As shown in Figure 7, the −OH peak (at 3437 cm–1) is associated with the stretching vibration of the NR, and the hydroxyl stretching vibration absorption peaks of the CGE/NR and the KH590-CGE/NR nanocomposites gradually became smaller. The C=C peak (at 2920 and 1635 cm–1) and the C–O peak (at 1099 cm–1) associated with the stretching vibration of the NR, and those peaks of CGE/NR and KH590-CGE/NR nanocomposites decreased gradually. This indicated that the chemical structure of the NR modified with CGE and KH590 was changed. It could be that one end of KH590 and NR was connected by chemical bonding and the other end of KH590 and CGE was connected by physical adsorption. In addition, the presence of the coupling agent KH590 could better combine CGE with NR and further reduce the number of double bonds in the composites. Moreover, the C–O bond was oxidized by the C=C bond, and the reduction of the C=C bond would correspondingly reduce the number of C–O bonds, thus improving the thermal stability of the NR more.

Figure 7.

FTIR spectra of NR and CGE/NR composites.

Conclusions

In summary, we have successfully prepared KH590-CGE/NR nanocomposites using a 2 phr KH590 coupling agent treated with 0.02 phr graphene and 100 phr natural rubber. Compared with NR, the thermal conductivity of the KH590-CGE/NR nanocomposites was improved by 6.0 mW/g, the decomposition temperature was increased by 37 °C, its tensile strength was increased by 16%, elongation at break was increased by 14%, and wear resistance was improved by 17%. The KH590-CGE/NR nanocomposites had the best compatibility and dispersibility.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- NR

natural rubber

- CGE

cornmeal graphene

- Accelerator M

2-mercapto-benzothiazole

- KH550

3-triethoxysilyl-1-propylamine

- KH590

3-mercaptopropyl trimethoxysilane

- Si69

bis-g-(triethoxysilane)

- DCP

dicumyl peroxide

- TG

thermogravimetric analyzer

- DSC

differential scanning calorimetry

- SEM

scanning electron microscopy

- FTIR

Fourier transform infrared spectrometer

Author Contributions

All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds in Heilongjiang Provincial Universities, China (No. YSTSXK201864).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Noor Azammi A. M.; Sapuan S. M.; Ishak M. R.; Sultan M. T. H. Mechanical and thermal properties of kenaf reinforced thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU)-natural rubber (NR) composites. Fibers Polym. 2018, 19, 446–451. 10.1007/s12221-018-7737-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harea E.; Stoček R.; Storozhuk L.; Sementsov Y.; Kartel N. Study of tribological properties of natural rubber containing carbon nanotubes and carbon black as hybrid fillers. Appl. Nanosci. 2019, 9, 899–909. 10.1007/s13204-018-0797-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xia L.; Wang Y.; Ma Z. G.; Xin Z. X. The organic–aqueous extraction of natural eucommia ulmoides rubber and its properties and application in car radial tires. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2017, 36, 295–300. 10.1002/adv.21607. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boothroyd S. C.; Johnson D. W.; Weir M. P.; Reynolds C. D.; Hart J. M.; Clarke N.; Thompson R. L.; Coleman K. S.; Smith A. J. Controlled structure evolution of graphene networks in polymer composites. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 1524–1531. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b04343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Down M. P.; Rowley-Neale S. J.; Smith G. C.; Banks C. E. Fabrication of graphene oxide supercapacitor devices. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018, 1, 707–714. 10.1021/acsaem.7b00164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Li H. Q.; Zhang L.; Lai X. J.; Wu W. J.; Zeng X. R. In situ preparation of reduced graphene oxide reinforced acrylic rubber by self-assembly. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47187–47192. 10.1002/app.47187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. H.; Cho M.; Nam J.-D.; Lee Y. Effect of ZnO particle sizes on thermal aging behavior of natural rubber vulcanizates. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2018, 148, 50–55. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2018.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W.; Cong S. Silica- and diatomite-modified fluorine rubber nanocomposites. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2019, 42, 176 10.1007/s12034-019-1867-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Zhang L.; Hou Z. Preparation and properties of graphene oxide/glycidyl methacrylate grafted natural rubber nanocomposites. J. Polym. Environ. 2017, 25, 315–322. 10.1007/s10924-016-0817-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bayat H.; Fasihi M. Effect of coupling agent on the morphological characteristics of natural rubber/silica composites foams. e-Polymers 2019, 19, 430–436. 10.1515/epoly-2019-0044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xue G.; Zhang B.; Xing J.; et al. A facile approach to synthesize in situ functionalized graphene oxide/epoxy resin nanocomposites: mechanical and thermal properties. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 13973–13989. 10.1007/s10853-019-03901-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanania S.; Mahata D.; Cornish K.; Nando G. B.; Chattopadhyay S.; Prabhavale O. Phosphorylated cardanol prepolymer grafted guayule natural rubber: an advantageous green natural rubber. Iran. Polym. J. 2018, 27, 307–318. 10.1007/s13726-018-0611-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alimardani M.; Razzaghi-Kashani M.; Koch T. Crack growth resistance in rubber composites with controlled Interface bonding and interphase content. J. Polym. Res. 2019, 26, 47 10.1007/s10965-019-1709-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.; Gao H.; Hu G. Highly sensitive natural rubber/pristine graphene strain sensor prepared by a simple method. Composites, Part B 2019, 171, 138–145. 10.1016/j.compositesb.2019.04.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Leon A. C.; Alonso L.; Mangadlao J. D.; Advincula R. C.; Pentzer E. Simultaneous reduction and functionalization of graphene oxide via ritter reaction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 14265–14272. 10.1021/acsami.7b01890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.; Huang G.; Li H.; Wu S.; Liu Y.; Zheng J. Enhanced mechanical and gas barrier properties of rubber nanocomposites low content. Polymer 2013, 54, 1930–1937. 10.1016/j.polymer.2013.01.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu D. H.; Zhan Y. H.; Yan N.; Xia H. S. A comparative investigation on strain induced crystallization for graphene and carbon nanotubes filled natural rubber composites. Express Polym. Lett. 2015, 9, 597–607. 10.3144/expresspolymlett.2015.56. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lai W.; Wang Z.; Li Y.; Wang X.; Liu X.; Liu Y. Radical mechanism for the reduction of graphene derivatives initiated by electron-transfer reactions. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 8473–8479. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b01941. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang W.; Ge X.; Ge J.; Li T.; Zhao T.; Chen X.; Song Y.; Cui Y.; Khan M.; Ji J.; Pang X.; Liu R. Reduced graphene oxide embedded with MQ silicone resin nano-aggregates for silicone rubber composites with enhanced thermal conductivity and mechanical performance. Polymer 2018, 10, 1254 10.3390/polym10111254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Zhang K.; Cheng Z.; Lavorgna M.; Xia H. Graphene/carbon black/natural rubber composites prepared by a wet compounding and latex mixing process. Plast., Rubber Compos. 2018, 47, 398–412. 10.1080/14658011.2018.1516435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lim L. P.; Juan J. C.; Huang N. M.; Goh L. K.; Leng F. P.; Loh Y. Y. Enhanced tensile strength and thermal conductivity of natural rubber graphene composite properties via rubber-graphene interaction. Mater. Sci. Eng., B 2019, 246, 112–119. 10.1016/j.mseb.2019.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong E.; Yoon B.; Nam J. D.; Suhr J. Accelerated aging and lifetime prediction of graphene-reinforced natural rubber composites. Macromol. Res. 2018, 26, 998–1003. 10.1007/s13233-018-6131-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.; Yao B.; Li C.; Shi G. An improved Hummers method for eco-friendly synthesis of graphene oxide. Carbon 2013, 64, 225–229. 10.1016/j.carbon.2013.07.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mun S. P.; Cai Z.; Zhang J. Fe-catalyzed thermal conversion of sodium lignosulfonate to graphene. Mater. Lett. 2013, 100, 180–183. 10.1016/j.matlet.2013.02.101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu H.; Kim Y. A.; Yang K. S.; Cruz-Silva R.; Toda I.; Yamada T.; Terrones M.; Endo M.; Hayashi T.; Saitoh H. Rice husk-derived graphene with nano-sized domains and clean edges. Small 2014, 10, 2766–2770. 10.1002/smll.201400017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Feng L.; Yang H.; Xin G.; Li W.; Zheng J.; Tian W.; Li X. Graphene oxide stabilized polyethylene glycol for heat storage. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 13233. 10.1039/c2cp41988b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus S. M.; Blaine R. L. Thermal conductivity of polymers, glasses and ceramics by modulated DSC. Thermochim. Acta 1994, 243, 231–239. 10.1016/0040-6031(94)85058-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merzlyakov M.; Schick C. Thermal conductivity from dynamic response of DSC. Thermochim. Acta 2001, 377, 183–191. 10.1016/S0040-6031(01)00553-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]