Abstract

A Zn(II)-based metal–organic framework (MOF) compound and MnO2 were used to prepare ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites for selective Sr2+ removal in aqueous solutions. The ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites were characterized by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy, thermogravimetric analysis, and Brunauer–Emmett–Teller surface area analysis. The functional groups, morphologies, thermal stabilities, and specific surface areas of the composites were suitable for Sr2+ adsorption. A maximum adsorption capacity of 147.094 mg g–1 was observed in batch adsorption experiments, and the sorption isotherms were fit well by the Freundlich model of multilayer adsorption. Adsorption reached equilibrium rapidly in kinetic experiments and followed the pseudo-second-order kinetic model. The adsorption capacity of the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composite with the highest MnO2 content was high over a wide pH range, and the composite was highly selective toward Sr2+ in solutions containing coexisting competing ions. Also, it has a good reusability for removing Sr2+.

Introduction

The strontium isotopes 89Sr and 90Sr are fission products found in wastes from nuclear power plants and nuclear fuel reprocessing.190Sr is a particularly hazardous radioactive contaminant because it emits high-energy 0.5460 MeV beta (β) particles and has a long half-life of 29 years.2 Because it is chemically similar to calcium, 90Sr in the human body can cause osteosarcoma and leukemia.3 Therefore, the removal of Sr2+ from aqueous media is essential to prevent harm to both the environment and human health. Numerous methods are available for removing Sr2+ from aqueous solutions, including chemical precipitation, solvent extraction, and adsorption.4,5 Among these techniques, adsorption is simple and well-suited to wastewater treatment.

The removal of Sr2+ using manganese(IV) oxide (MnO2) has been reported by several researchers.6−8 MnO2 particles have a large Sr2+ sorption capacity, and they are selective for Sr2+ in the presence of competing ions such as Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+.6,9 In the present paper, the adsorption of Sr2+ onto MnO2 is highlighted. However, MnO2 nanoparticles have drawbacks, such as a tendency to agglomerate because of van der Waals forces and other interactions. The nanoparticles are also difficult to separate from treated wastewater after adsorption.10 Nanoparticulate MnO2 must therefore be immobilized onto a support to enhance its Sr2+ adsorption efficiency and reusability.11 Potentially suitable solid supports for immobilized MnO2 nanoparticles include carbon nanotubes,12 mesoporous silica,11 graphene oxide,13 and metal–organic frameworks (MOFs).14 Among these candidates, MOFs are particularly attractive because of their high removal efficiency.15,16 In particular, MOFs have been used as adsorbents for removal of alkaline-earth-metal ions in several studies.17−19 MOFs are porous materials composed of metal ions and organic ligands linked through coordinate bonds.20 MOFs have several unique advantages. Depending on their metal constituents and organic ligands, MOFs can exhibit various morphologies. MOFs also feature large specific surface areas, and their pore sizes can be controlled.21,22 Highly porous MOFs with a carefully designed pore space have been shown to capture metal ions and various pollutants.23−25 The Zn(II)-based ZnOx-MOF has not been widely studied for Sr2+ adsorption. The advantages of the ZnOx-MOF include a facile synthesis from inexpensive starting materials.26,27 ZnOx-MOF has a three-dimensional (3D) crystalline structure with cavities for metal ions.14,28

The aim of the present study was to synthesize ZnOx-MOF/MnO2 (ZnOx-MOF@MnO2) composites for the adsorption of Sr2+ in aqueous media. A ZnOx-MOF was impregnated with MnO2 particles via alkali precipitation. To improve the Sr2+ adsorption capacity of the ZnOx-MOF, we prepared ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites with different MnO2 contents. The ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites were then characterized using several analytical techniques. Finally, Sr2+ adsorption by the composites was tested under various conditions. Several isotherm and kinetic models were applied to the experimental data to analyze the Sr2+ adsorption behavior of the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites.

Results and Discussion

Characterization of ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 Composites

The FT-IR spectra of the ZnOx-MOF and the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites are shown in Figure 1. The spectrum of the ZnOx-MOF includes the various peaks reported by Kabir et al.27 Specifically, the ZnOx-MOF spectrum shows a broad peak from 3350 to 3570 cm–1, which is attributed to O–H groups participating in hydrogen bonding with cations. The broad peak from 1005 to 1120 cm–1 is ascribed to O–H groups participating in hydrogen bonding with SO42– anions. C–O–C symmetric stretching vibrations are observed at 982, 1147, and 2988 cm–1 in the spectrum of the ZnOx-MOF.29 The peaks at 1055 and 1202 cm–1 are attributed to a SO3– vibrational band. The peaks from 2800 to 2300 cm–1 are attributed to C–H stretching vibrations in the ZnOx-MOF. Some peaks disappeared after the addition of MnO2, and the spectra of the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 were nearly identical to each other irrespective of the MnO2 concentration. The peak at 538 cm–1 was attributed to Mn–O bonds in the MnO2 structure. The O–H vibrations in the spectra of the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites were the same as those observed from 3200 to 3600 cm–1 in the ZnOx-MOF spectrum. The vibrations of O–H groups interacting with adsorbed Mn2+ were observed at 1166, 1172, and 1357 cm–1,30 whereas hydrogen bonding was indicated by the band at 2081 cm–1. In the spectra of both ZnOx-MOF and ZnOx-MOF@MnO2, sharp peaks ascribed to O–H vibrations were observed at 1727 cm–1.

Figure 1.

FT-IR spectra of the ZnOx-MOF and the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites.

The powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns of the ZnOx-MOF and the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites are shown in Figure 2. In the ZnOx-MOF, 3D hydrogen bonding appeared, indicating interaction between the dimethylammonium cations and sulfate anions.26 As indicated by the peaks in the pattern of ZnOx-MOF, the ZnOx-MOF composite was confirmed to be highly crystalline. The PXRD patterns of composites ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (1), (2), and (3) showed broad, low-intensity peaks; however, a peak attributed to MnO2 (ramsdellite) was observed at 22 ≤ 2θ ≤ 25°.31 Obviously, the strong XRD intensity in ZnOx-MOF significantly lowered the XRD peak through impregnated MnO2 particles. Therefore, it is considered that some frameworks have the potential to be destroyed during the MnO2 precipitation process.

Figure 2.

PXRD patterns of the ZnOx-MOF and the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites.

The morphologies of the ZnOx-MOF and the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites were investigated via SEM (Figure 3). The micrographs of the ZnOx-MOF show cubic structures and a rough surface. The specimen had a large surface area and pore size, and its morphology was similar to that of a reference sample of ZnOx-MOF.27 The ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites exhibited the same spherical morphology irrespective of their MnO2 content. The magnified image of the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites in Figure 2 reveals nanowire-like structures that joined to form spherical shapes around the ZnOx-MOF composite particles.32,33

Figure 3.

SEM images of the ZnOx-MOF and the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites.

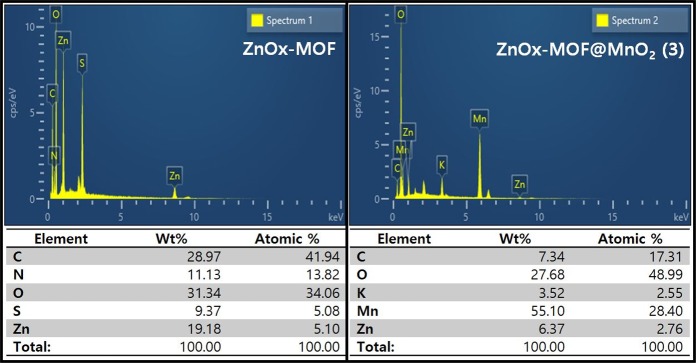

The contents of MnO2 in the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) composites were confirmed by SEM-EDS (Figure 4). EDS analysis analyzes the content according to the sensitivity of each element. Elements such as O and N have low sensitivity, which reduces the accuracy.34 However, Zn and Mn have high sensitivity and reliable results. Therefore, ZnOx-MOF has Zn and S contents of 5.10 and 5.08 at. %, respectively, and in addition, it was confirmed that the ZnOx-MOF was well synthesized with high contents of C, N, and O. This may support the results of the FT-IR (Figure 1). In addition, ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) was found to have 2.55 at. % K content using KMnO4, and the MnO2 content of ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) was about 28.4%. Accordingly, ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (1), ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (2), and ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3), which were synthesized from MnSO4 and KMnO4 by ratio, were approximately 5.68, 11.36, and 28.4% in ZnOx-MOF@MnO2, respectively.

Figure 4.

Results of SEM-EDS of the ZnOx-MOF and the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) composites.

The thermal stabilities of the ZnOx-MOF and the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites were compared on the basis of their mass losses during thermal decomposition (Figure 5). The ZnOx-MOF composite was stable to 210 °C, and its mass did not change. However, it lost mass rapidly at higher temperatures. The ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 components lost between 10 and 20% of their mass when heated to 1000 °C. Among the three composites, ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3), which had the highest MnO2 content, was the most thermally stable.

Figure 5.

TGA curves of the ZnOx-MOF and the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites.

The surface areas, pore sizes, and pore volumes of the samples were determined via Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis. The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms are shown in Figure 6, and Table 1 summarizes the physical properties of the ZnOx-MOF and the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites. The MOF structure of the ZnOx-MOF exhibited a small surface area of 64.11 m2 g–1, which was not sufficient for Sr2+ adsorption. The ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites, in which MnO2 was combined with the ZnOx-MOF, exhibited larger surface areas than the ZnOx-MOF. The surface area of each of the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites exceeded 100 m2 g–1, which indicates that the adsorbents had suitable physical properties. The pore sizes and volumes of the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites were also suitable for Sr2+ adsorption and were slightly larger than those of the ZnOx-MOF.

Figure 6.

N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of the ZnOx-MOF and the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites.

Table 1. Physical Properties of the ZnOx-MOF and the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 Composites.

| composite | BET surface area (m2 g–1) | pore size (Å) | pore volume (cm3 g–1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ZnOx-MOF | 64.11 | 33.92 | 0.085 |

| ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (1) | 162.73 | 38.39 | 0.427 |

| ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (2) | 137.78 | 37.34 | 0.124 |

| ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) | 122.18 | 37.26 | 0.091 |

Equilibrium Adsorption Isotherms

The experimental adsorption isotherms were fitted using the Langmuir,35 Freundlich,36 and Temkin37 equilibrium isotherm models. The equations for the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin models are expressed in eqs 1–3, respectively

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

where qm is the maximum adsorption capacity of the adsorbent (mg g–1). In eq 1, b is the Langmuir adsorption constant related to the free energy of adsorption (L mg–1). Kf [(mg g–1)(L mg–1)1/n] and n in the Freundlich model are constants. KT (L g–1) and B (L mg–1) in eq 3 are isotherm constants, and R (8.314 J mol–1 K–1) is the universal gas constant.

The error was evaluated by analyzing the correlation coefficient (r2) and chi-squared (χ2) values.38 The χ2 values were calculated using eq 4

| 4 |

where qe,calc and qe,exp are the calculated and experimental qe values, respectively.

The Sr2+ adsorption isotherms of the MnO2, ZnOx-MOF, ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (1), ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (2), and ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) are shown in Figure 7. The experimental data were subjected to regression analysis after fitting with the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin isotherm models. The parameters of each isotherm model are listed for MnO2, ZnOx-MOF, and each of the composites in Table 2. Although MnO2 and ZnOx-MOF themselves exhibited good Sr2+ adsorption, the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites exhibited higher adsorption capacities. On the basis of the Langmuir model, ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) exhibited a maximum adsorption capacity of 147.094 mg g–1. This result confirms that the number of Sr2+ adsorption sites depended on the MnO2 concentration. Thus, increasing the MnO2 concentration resulted in a higher adsorption capacity. The Langmuir model afforded the best fit for the ZnOx-MOF adsorption isotherm data (r2 = 0.961), indicating monolayer adsorption of Sr2+ onto the ZnOx-MOF composite. By contrast, the best fits of the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composite isotherm data were obtained with the Freundlich model (r2 > 0.98), suggesting multilayer adsorption. Moreover, Sr2+ adsorption on MnO2 particles was also most suitable for Freundlich. The Temkin isotherm was well-suited for Sr2+ adsorption onto the ZnOx-MOF; however, the Temkin r2 values of MnO2 and ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites were low. The ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) composite exhibited an adsorption capacity (qm) for Sr greater than those of previously reported adsorbents (Table 3). Among the previously reported adsorbents, MOF/KNiFC, MOF/Fe3O4/KNiFC, and Nd-BTC MOF are MOF-based adsorbents.

Figure 7.

Sr2+ adsorption isotherms of MnO2, ZnOx-MOF, and the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites.

Table 2. Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin Isotherm Model Parameters.

| model | parameter | MnO2 | ZnOx-MOF | ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (1) | ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (2) | ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir | qm (mg g–1) | 95.512 | 101.985 | 112.820 | 135.049 | 147.094 |

| b (L mg–1) | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.008 | 0.028 | 0.048 | |

| r2 | 0.994 | 0.961 | 0.954 | 0.915 | 0.937 | |

| χ2 | 1.380 | 43.162 | 53.985 | 176.608 | 183.616 | |

| Freundlich | Kf [(mg g–1)(L mg–1)1/n] | 0.635 | 1.582 | 2.007 | 3.202 | 3.358 |

| n | 1.382 | 2.393 | 5.615 | 21.760 | 28.256 | |

| r2 | 0.996 | 0.917 | 0.981 | 0.982 | 0.992 | |

| χ2 | 0.868 | 92.514 | 22.836 | 36.764 | 22.378 | |

| Temkin | KT (L g–1) | 0.110 | 0.087 | 0.812 | 12.328 | 14.661 |

| B (L mg–1) | 9.861 | 24.483 | 14.436 | 21.723 | 21.844 | |

| r2 | 0.859 | 0.945 | 0.790 | 0.843 | 0.877 | |

| χ2 | 34.129 | 61.367 | 246.412 | 325.058 | 357.946 |

Table 3. Comparison of Maximum Adsorption Capacities Reported in Various Studies.

| adsorbent | maximum adsorption capacity (qm) | ref |

|---|---|---|

| ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) | 147.094 mg g–1 (1.689 mmol g–1) | this study |

| MOF/KNiFC | 110 mg g–1 | (39) |

| MOF/Fe3O4/KNiFC | 90 mg g–1 | (39) |

| Nd-BTC MOF | 58 mg g–1 | (40) |

| MnO2–alginate beads | 102.0 mg g–1 | (7) |

| bacterial cellulose membrane (BCM) | 44.86 mg g–1 | (41) |

| hydroxyapatite (HAP) | 27 μmol g–1 | (42) |

| CTS-g-AMPS-PANI | 88.89 mg g–1 | (43) |

| TNTs@DCH18C6 | 48.97 mg g–1 | (44) |

| alginate microspheres | 110 mg g–1 | (45) |

| Fe3O4@titanate fibers | 37.1 mg g–1 | (46) |

The adsorption is greatly dependent on the cation content of solution and binding sites of the adsorbent.47,48 To investigate the affinity of the adsorbent for the Sr2+ adsorption, distribution coefficient (Kd) was calculated by

| 5 |

Herein, Co and Ce are the initial and effluent concentrations (mg L–1) of Sr2+ in the solution, respectively. V is solution volume (mL), and m represents the mass of the adsorbent (g).

Table 4 shows the distribution coefficients of the ZnOx-MOF and the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites in experimental ranges. The experiments were conducted in 10–400 ppm Sr2+. It is shown that the Kd value increased as the MnO2 concentration increased. ZnOx-MOF showed the highest Kd value at 100 ppm, and ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites all showed the highest Kd value at 10 ppm. This means that, in the case of ZnOx-MOF@MnO2, ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 can be efficiently adsorbed even at a low concentration of Sr2+. Normally, the adsorption process is not efficient at low concentrations because it is hardly adsorbed at low concentrations even if the qe value is very high at high concentrations. However, it was confirmed that the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 synthesized in this study has a high partition coefficient in a wide range from low concentration to high concentration and is effective in various ranges.

Table 4. Distribution Coefficient (Kd) Values of the ZnOx-MOF and the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 Composites.

| parameter | concentration | ZnOx-MOF | ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (1) | ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (2) | ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kd (mL g–1) | 10 ppm | 206.89 | 9724.12 | 136630.8 | 205006.6 |

| 20 ppm | 292.99 | 3473.08 | 173978.4 | 182673.5 | |

| 50 ppm | 428.37 | 936.95 | 3911.89 | 6344.85 | |

| 100 ppm | 697.06 | 791.09 | 1742.48 | 3300.43 | |

| 200 ppm | 472.26 | 472.76 | 792.50 | 1050.19 | |

| 300 ppm | 345.58 | 419.58 | 619.46 | 786.61 | |

| 400 ppm | 266.99 | 322.96 | 461.91 | 593.67 |

Adsorption Kinetics

The adsorption behaviors of the composites depended on the duration of contact with the solution. The data was fit using the Lagergren pseudo-first-order49 and pseudo-second-order50 models

| 6 |

and

| 7 |

where qt and qe are the Sr2+ concentrations at time t and at equilibrium, respectively (mg g–1), k1 is the pseudo-first-order constant (min–1), and k2 is the pseudo-second-order constant (g mg–1 min–1).

Nonlinear fits of the experimental concentration vs contact time data obtained with the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models are shown in Figure 8. Sr2+ adsorption proceeded rapidly, and 50% of the maximum adsorption capacity at each concentration was attained within 5 min. The higher the concentration of Sr2+, the faster the equilibrium is achieved. The calculated pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order parameters are shown in Table 5. The kinetic behaviors of the composites were best fit with the pseudo-second-order model. The time required to reach equilibrium decreased with increasing Sr2+ concentration, and the corresponding qe values were higher. The results indicate that the adsorption contact time in the isotherm experiments was sufficient.

Figure 8.

Nonlinear Sr2+ adsorption kinetics on the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) composite at initial Sr2+ concentrations of 50, 100, and 200 ppm.

Table 5. Pseudo-first-order and Pseudo-second-order Kinetic Model Parameters for Sr2+ Adsorption at Initial Concentrations of 50, 100, and 200 ppm Using ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3).

| pseudo-first-order model |

pseudo-second-order model |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Sr2+] (ppm) | qe (mg g–1) | k1 (min–1) | r2 | χ2 | qe (mg g–1) | k2 (g mg–1 min–1) | r2 | χ2 |

| 50 | 47.055 | 0.337 | 0.975 | 0.0024 | 48.808 | 0.015 | 0.994 | 0.0006 |

| 100 | 71.201 | 0.193 | 0.942 | 0.0034 | 76.121 | 0.004 | 0.981 | 0.0011 |

| 200 | 88.816 | 0.183 | 0.922 | 0.0028 | 94.956 | 0.003 | 0.968 | 0.0007 |

pH Effect of Sr2+ Adsorption

The pH of a solution strongly influences Sr2+ adsorption.51 The effect of pH on Sr2+ adsorption by ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) was investigated in the pH range of 1 to 11 (Figure 9). At low pH (pH 1), the adsorption capacity (qe) was low; Qe values were higher in the range of pH 5 to 11, as determined on the basis of the point-of-zero charge (pHpzc). pHpzc is the point at which the net total charge on the particle is zero. A pHpzc value of 6.4 was obtained from the plot of initial pH vs the difference between the initial and final pH levels (Figure 10). The ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) composite was positively charged above pH 6.4. Adsorption of Sr2+ onto the composite was inhibited in acidic conditions because of interference by H+ ions.52

Figure 9.

Effect of pH on Sr2+ adsorption by the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) composite.

Figure 10.

Point-of-zero charge (pHpzc) of the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) composite.

Sr2+ Selectivity

Figure 11 shows the impact of competing cations on the Sr2+ adsorption capacity of ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3). The concentrations of Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ ranged from 50 to 400 ppm in a 200 ppm Sr2+ solution. In a pure 200 ppm Sr2+ solution, the qe of ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) for Sr2+ was 108.51 mg g–1. However, the concentrations of coexisting cations affected the adsorption capacity of the composite. The divalent Ca2+ and Mg2+ cations, in particular, reduced Sr2+ adsorption. Ca2+ interfered most with Sr2+ adsorption because Ca2+ has an ionic radius very similar to Sr2+.7 However, seawater contains a higher concentration of Na+, which does not substantially affect the removal of Sr2+.

Figure 11.

Effect of competing cations on Sr2+ adsorption by the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) composite.

Reusability

The results of three consecutive adsorption–desorption experiments are shown in Figure 12. When 0.1 N HNO3 solution, a desorption solution, was used, a desorption rate of 88.28% was obtained from the adsorbent adsorbed with Sr2+ once. The adsorption and desorption of the desorbed adsorbents were conducted two and three times, respectively. The adsorption rates decreased by 6.86 and 14.91%, respectively, and the desorption rates decreased by 86.29 and 78.01%. However, Sr2+ was sufficiently desorbed with 0.1 N HNO3, and the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) adsorbent was judged to be reusable. Additionally, it is confirmed that 0.5 N HNO3 or more was required to complete desorption of Sr2+ and that no leaching of the adsorbent metal was observed.

Figure 12.

Reusability assessment of the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) composite by sequential adsorption–desorption.

Conclusions

A Zn(II)-based ZnOx-MOF was successfully combined with MnO2 particles to afford ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites for Sr2+ adsorption in aqueous solutions. The adsorption isotherms of the composites confirmed that the adsorption capacity increased with increasing MnO2 content. The ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) composite exhibited a maximum Sr2+ adsorption capacity of 147.094 mg g–1 on the basis of the Langmuir isotherm model. Its goodness of fit was highest with the Freundlich model of multilayer adsorption. Evaluation of the effects of pH, contact time, and coexisting ions confirmed that adsorbent sites were available within a wide pH range (5–11). Adsorption equilibrium was reached rapidly, and the selectivities of the composites for Sr2+ were high. Therefore, the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites can be used for the selective removal of Sr2+ in actual radioactive liquid waste.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Zinc sulfate heptahydrate (ZnSO4·7H2O, 99%, MW 287.56 g mol–1), potassium sulfate (K2SO4, 99%, MW 174.24 g mol–1), sodium chloride (NaCl, 99%, MW 58.44 g mol–1), anhydrous magnesium sulfate (MgSO4, 99%, MW 120.37 g mol–1), and ethyl alcohol (C2H5OH, 94%) were purchased from Duksan Pure Chemicals (South Korea). N,N-Dimethylformamide (C3H7NO, 99.5%, MW 73.1 g mol–1), oxalic acid dihydrate (H2C2O4·2H2O, 99.5–100.2%, MW 126.07 g mol–1), 5 N sodium hydroxide standard solution, potassium permanganate (KMnO4, 99.3%, MW 158.03 g mol–1), and manganese(II) sulfate pentahydrate (MnSO4·5H2O, 98%, MW 241.08 g mol–1) were purchased from Daejung Chemicals & Metals (South Korea). Calcium sulfate dihydrate (CaSO4·2H2O, 95%, MW 172.17 g mol–1) was purchased from Oriental Chemical Industries (South Korea). Strontium nitrate (Sr(NO3)2, 99%, MW 211.63 g mol–1) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA) and used to prepare simulant solutions. All solutions were prepared with deionized (D.I.) water (EXL 5 A16, EXL Service, USA).

Synthesis of ZnOx-MOF

ZnOx-MOF was synthesized using the method reported by Kabir et al.27 ZnSO4·7H2O (1 mmol) and H2C2O4·2H2O (2.50 mmol) were dissolved in 10 mL of N,N-dimethylformamide. The solution was stirred at 200 rpm for 30 min and then reacted in a Teflon-lined autoclave at 160 °C for 4 days. The obtained white product was washed several times with ethyl alcohol and dried for 24 h at 60 °C in a vacuum oven.

Synthesis of ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 Composites

Dark-violet solutions were obtained by mixing KMnO4 and MnSO4·5H2O. The prepared ZnOx-MOF powder (1 g) was added to each solution, and the solutions were stirred for 1 h. The solutions had initial pH values of 1–2, which were adjusted to between 8 and 9.5 using 5 N NaOH. The pH remained stable, and the color of the solutions changed from purple to brown. The brown ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 powders were allowed to settle and then collected via filtration using 0.2 μm filters. The powders were washed several times with D.I. water to remove unreacted chemicals. The final products were dried in a 60 °C oven. The Sr2+ adsorption capacity was enhanced with increasing MnO2 content of the composites. ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (1), ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (2), and ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) were prepared using 0.02, 0.04, and 0.1 M KMnO4 along with 0.028, 0.056, and 0.14 M MnSO4·5H2O, respectively.

Characterization of ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 Composites

FT-IR analysis was performed on a Frontier spectrometer (PerkinElmer, USA). The morphologies of the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites were analyzed using an SU8220 field-emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, Hitachi, Japan). The thermal properties of the composites were characterized using a Q600 thermogravimetric analyzer (TA Instruments, Japan). The specific surface areas, pore volumes, and pore sizes of the ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 composites were determined via BET analysis using Autosorb-iQ and Quadrasorb SI gas sorption analyzers (Quantachrome Instruments, USA).

Adsorption Experiments

All experiments were performed in duplicate in a batch system using 15 mL polyethylene conical tubes (SPL, South Korea). Simulant solutions with Sr2+ concentrations ranging from 10 to 400 mg L–1 were prepared for the adsorption experiments. Each of the synthesized composites (10 mg) was contacted with a Sr2+ solution (10 mL) at 250 rpm for 24 h at room temperature. For the kinetic experiments, the samples were suspended in 100, 200, and 300 mg L–1 Sr2+ solutions and contacted for various time intervals. Solutions containing 200 ppm Sr2+ were prepared over a range of pH values to evaluate the effect of pH on Sr2+ adsorption. The effect of coexisting ions (i.e., Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+) on Sr2+ adsorption was evaluated using 200 ppm Sr2+ solutions. To investigate the reusability of adsorbent, three consecutive adsorption–desorption experiments were conducted using 0.1 N HNO3 as the desorption solution. The ZnOx-MOF@MnO2 (3) adsorbent was used for the kinetics, pH, competitive adsorption, and reusability experiments. All of the samples were centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 10 min. The solids were removed via filtration using 0.20 μm nitrocellulose membrane filters (Whatman, USA). The Sr2+ concentrations in the filtered solutions were determined using an Optima 2100DV inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (PerkinElmer, USA).

The equilibrium adsorption capacity (qe, mg g–1) was calculated using eq 8

| 8 |

where Co and Ce are the initial and equilibrium Sr2+ concentrations, respectively, in mg L–1, V is the volume of the Sr2+ simulant solution (mL), and W is the weight of the adsorbent (g).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Nuclear Energy Development Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (2018M2B2B1065631).

Author Contributions

‡ J.-W.C. and Y.-J.P. contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Chakraborty D.; Maji S.; Bandyopadhyay A.; Basu S. Biosorption of cesium-137 and strontium-90 by mucilaginous seeds of Ocimum basilicum. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 2949–2952. 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusan S.; Erenturk S. Adsorption characterization of strontium on PAN/zeolite composite adsorbent. World J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2011, 01, 6. 10.4236/wjnst.2011.11002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.-P. Batch and continuous adsorption of strontium by plant root tissues. Bioresour. Technol. 1997, 60, 185–189. 10.1016/S0960-8524(97)00021-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C.; Wang J.; Chen J. Solvent extraction of strontium and cesium: a review of recent progress. Solvent Extr. Ion Exch. 2012, 30, 623–650. 10.1080/07366299.2012.700579. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J.-G.; Gu P.; Zhao J.; Zhang D.; Deng Y. Removal of strontium from an aqueous solution using co-precipitation followed by microfiltration (CPMF). J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2010, 285, 539–546. 10.1007/s10967-010-0564-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi S. J.; Akbari N.; Shiri-Yekta Z.; Mashhadizadeh M. H.; Hosseinpour M. Removal of strontium ions from nuclear waste using synthesized MnO2-ZrO2 nano-composite by hydrothermal method in supercritical condition. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2015, 32, 478–485. 10.1007/s11814-014-0249-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong H.-J.; Kim B.-G.; Hong J.; Ryu J.; Ryu T.; Chung K.-S.; Kim H.; Park I.-S. Enhanced Sr adsorption performance of MnO2-alginate beads in seawater and evaluation of its mechanism. Chem. Eng. 2017, 319, 163–169. 10.1016/j.cej.2017.02.132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanets A. I.; Katsoshvili L. L.; Krivoshapkin P. V.; Prozorovich V. G.; Kuznetsova T. F.; Krivoshapkina E. F.; Radkevich A. V.; Zarubo A. M. Sorption of strontium ions onto mesoporous manganese oxide of OMS-2 type. Radiochemistry 2017, 59, 264–271. 10.1134/S1066362217030080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi S. J.; Akbari N.; Shiri-Yekta Z.; Mashhadizadeh M. H.; Pourmatin A. Adsorption of strontium ions from aqueous solution using hydrous, amorphous MnO2–ZrO2 composite: a new inorganic ion exchanger. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2014, 299, 1701–1707. 10.1007/s10967-013-2852-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke T. D.; Wai C. M. Selective removal of cesium from acid solutions with immobilized copper ferrocyanide. Anal. Chem. 1998, 70, 3708–3711. 10.1021/ac971138b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. K.; Yang D. S.; Oh W.; Choi S.-J. Copper Ferrocyanide Functionalized Core–Shell Magnetic Silica Composites for the Selective Removal of Cesium Ions from Radioactive Liquid Waste. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2016, 16, 6223–6230. 10.1166/jnn.2016.10886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong Y.-C.; Dong X.-C.; Chan-Park M. B.; Song H.; Chen P. Macroporous and Monolithic Anode Based on Polyaniline Hybridized Three-Dimensional Graphene for High-Performance Microbial Fuel Cells. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 2394. 10.1021/nn204656d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasap S.; Aslan E. N.; Öztürk İ. Investigation of MnO2 nanoparticles-anchored 3D-graphene foam composites (3DGF-MnO2) as an adsorbent for strontium using the central composite design (CCD) method. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 2981–2989. 10.1039/C8NJ05283B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Naeimi S.; Faghihian H. Performance of novel adsorbent prepared by magnetic metal-organic framework (MOF) modified by potassium nickel hexacyanoferrate for removal of Cs+ from aqueous solution. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 175, 255–265. 10.1016/j.seppur.2016.11.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Eddaoudi M.; O’Keeffe M.; Yaghi O. M. Design and synthesis of an exceptionally stable and highly porous metal-organic framework. Nature 1999, 402, 276. 10.1038/46248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S.-N.; Krishnaraj C.; Jena H. S.; Poelman D.; Van Der Voort P. An anionic metal-organic framework as a platform for charge-and size-dependent selective removal of cationic dyes. Dyes Pigm. 2018, 156, 332–337. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2018.04.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y.; Huang H.; Liu D.; Zhong C. Radioactive barium ion trap based on metal–organic framework for efficient and irreversible removal of barium from nuclear wastewater. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 8527–8535. 10.1021/acsami.6b00900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springthorpe S. K.; Dundas C. M.; Keitz B. K. Microbial reduction of metal-organic frameworks enables synergistic chromium removal. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–11. 10.1038/s41467-019-13219-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abney C. W.; Taylor-Pashow K. M. L.; Russell S. R.; Chen Y.; Samantaray R.; Lockard J. V.; Lin W. Topotactic transformations of metal–organic frameworks to highly porous and stable inorganic sorbents for efficient radionuclide sequestration. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 5231–5243. 10.1021/cm501894h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Decker J.; Folens K.; De Clercq J.; Meledina M.; Van Tendeloo G.; Du Laing G.; Van Der Voort P. Ship-in-a-bottle CMPO in MIL-101 (Cr) for selective uranium recovery from aqueous streams through adsorption. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 335, 1–9. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L. J.; Dincă M.; Long J. R. Hydrogen storage in metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 1294–1314. 10.1039/b802256a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L.; Tu B.; Qi Y.; Gao Q.; Liu D.; Liu Z.; Zhao L.; Li Q.; Zhao Y. Enhanced performance in gas adsorption and Li ion batteries by docking Li+ in a crown ether-based metal–organic framework. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 3003–3006. 10.1039/C5CC09935H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Wang X.; Zhao G.; Chen C.; Chai Z.; Alsaedi A.; Hayat T.; Wang X. Metal–organic framework-based materials: superior adsorbents for the capture of toxic and radioactive metal ions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 2322–2356. 10.1039/C7CS00543A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai A. V.; Manna B.; Karmakar A.; Sahu A.; Ghosh S. K. A Water-Stable Cationic Metal–Organic Framework as a Dual Adsorbent of Oxoanion Pollutants. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 7811–7815. 10.1002/anie.201600185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.; Pang H.; Yao W.; Wang X.; Yu S.; Yu Z.; Wang X. Synthesis of rod-like metal-organic framework (MOF-5) nanomaterial for efficient removal of U(VI): batch experiments and spectroscopy study. Sci. bull. 2018, 63, 831–839. 10.1016/j.scib.2018.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagarkar S. S.; Unni S. M.; Sharma A.; Kurungot S.; Ghosh S. K. Two-in-One: Inherent Anhydrous and Water-Assisted High Proton Conduction in a 3D Metal–Organic Framework. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 2638–2642. 10.1002/anie.201309077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabir M. D. L.; Kim H. J.; Choi S.-J. Highly Proton Conductive Zn(II)-Based Metal-Organic Framework/Nafion® Composite Membrane for Fuel Cell Application. Sci. Adv. 2018, 10, 1630–1635. 10.1166/sam.2018.3355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Q.-x.; Song X.-d.; Ji M.; Park S.-E.; Hao C.; Li Y.-q. Molecular size- and shape-selective Knoevenagel condensation over microporous Cu3(BTC)2 immobilized amino-functionalized basic ionic liquid catalyst. Appl. Catal., A 2014, 478, 81–90. 10.1016/j.apcata.2014.03.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.-R.; Li S.-L.; Zhang X.-M. D3-Symmetric Supramolecular Cation {(Me2NH2)6 (SO4)}4+ As a New Template for 3D Homochiral (10, 3)-a Metal Oxalates. Cryst. Growth Des. 2009, 9, 1702–1707. 10.1021/cg800522h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mylarappa M.; Lakshmi V. V.; Mahesh K. V.; Nagaswarupa H.; Raghavendra N.. A facile hydrothermal recovery of nano sealed MnO2 particle from waste batteries: An advanced material for electrochemical and environmental applications. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, IOP Publishing: 2016; p 012178.

- Pirsarael S. R. A.; Mahabadi H. A.; Jafari A. J. Airborne toluene degradation by using manganese oxide supported on a modified natural diatomite. J. Porous Mater. 2016, 23, 1015–1024. 10.1007/s10934-016-0159-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan Y.; Durrani S. K.; Mehmood M.; Khan M. R. Mild hydrothermal synthesis of γ-MnO2 nanostructures and their phase transformation to α-MnO2 nanowires. J. Mater. Res. 2011, 26, 2268–2275. 10.1557/jmr.2011.138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Luo C.; Sun J.; Li H.; Sun Z.; Yan S. Enhanced adsorption removal of methyl orange from aqueous solution by nanostructured proton-containing δ-MnO2. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 5674–5682. 10.1039/C4TA07112C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laskin A.; Cowin J. P. Automated single-particle SEM/EDX analysis of submicrometer particles down to 0.1 μm. Anal. Chem. 2001, 73, 1023–1029. 10.1021/ac0009604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmuir I. The Constitution and fundamental properties of solids and liquids. Part I. Solids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1916, 38, 2221–2295. 10.1021/ja02268a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freundlich H. M. F. Over the adsorption in solution. J. Phys. Chem 1906, 57, 1100. [Google Scholar]

- Tempkin M. I.; Pyzhev V. Kinetics of ammonia synthesis on promoted iron catalyst. Acta Phys. Chim. USSR 1940, 12, 327. [Google Scholar]

- Ho Y.-S.; Chiu W.-T.; Wang C.-C. Regression analysis for the sorption isotherms of basic dyes on sugarcane dust. Bioresour. Technol. 2005, 96, 1285–1291. 10.1016/j.biortech.2004.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeimi S.; Faghihian H. Modification and magnetization of MOF (HKUST-1) for the removal of Sr2+ from aqueous solutions. Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic modeling studies. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 2899–2908. 10.1080/01496395.2017.1375527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asgari P.; Mousavi S. H.; Aghayan H.; Ghasemi H.; Yousefi T. Nd-BTC metal-organic framework (MOF); synthesis, characterization and investigation on its adsorption behavior toward cesium and strontium ions. Microchem. J. 2019, 150, 104188. 10.1016/j.microc.2019.104188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng R.; Kang M.; Zhuang S.; Shi L.; Zheng X.; Wang J. Adsorption of Sr(II) from water by mercerized bacterial cellulose membrane modified with EDTA. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 364, 645–653. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.10.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama Y.; Hanafusa T.; Yamashita J.; Yamamoto Y.; Ono T. Adsorption and removal of strontium in aqueous solution by synthetic hydroxyapatite. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2016, 307, 1279–1285. 10.1007/s10967-015-4228-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T.; Zhu Y.; Wang W.; Qi Y.; Wang A. Polyaniline-functionalized porous adsorbent for Sr 2+ adsorption. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2018, 317, 907–917. 10.1007/s10967-018-5935-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J.; Zhang Y.; Ouyang J.; Wu X.; Luo J.; Liu S.; Gong X. A facile preparation of dicyclohexano-18-crown-6 ether impregnated titanate nanotubes for strontium removal from acidic solution. Solid State Sci. 2019, 90, 49–55. 10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2019.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong H.-J.; Ryu J.; Park I.-S.; Ryu T.; Chung K.-S.; Kim B.-G. Investigation of the strontium (Sr (II)) adsorption of an alginate microsphere as a low-cost adsorbent for removal and recovery from seawater. J. Environ. Manage. 2016, 165, 263–270. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi R.; Ye G.; Chen J. Synthesis of core–shell magnetic titanate nanofibers composite for the efficient removal of Sr(ii). RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 27242–27249. 10.1039/C9RA06148G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryxell G. E.; Lin Y.; Fiskum S.; Birnbaum J. C.; Wu H.; Kemner K.; Kelly S. Actinide sequestration using self-assembled monolayers on mesoporous supports. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 1324–1331. 10.1021/es049201j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y.; Kim C.; Choi S.-J. Selective removal of Cs using copper ferrocyanide incorporated on organically functionalized silica supports. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2015, 303, 199–208. 10.1007/s10967-014-3337-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett J. F. Pseudo first-order kinetics. J. Chem. Educ. 1972, 49, 663. 10.1021/ed049p663. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Y.-S.; McKay G. Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process Biochem. 1999, 34, 451–465. 10.1016/S0032-9592(98)00112-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.-X.; Hong G.-B. Adsorption behavior of modified Glossogyne tenuifolia leaves as a potential biosorbent for the removal of dyes. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 252, 289–295. 10.1016/j.molliq.2017.12.142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H.-K.; Choi J. W.; Oh W.; Choi S.-J. Sorption of cesium ions from aqueous solutions by multi-walled carbon nanotubes functionalized with copper ferrocyanide. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2016, 309, 477–484. 10.1007/s10967-015-4642-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]