Functional recovery after cortical injury, such as stroke, is associated with neural circuit reorganization, but the underlying mechanisms and efficacy of therapeutic interventions promoting neural plasticity in primates are not well understood. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles (MSC-EVs), which mediate cell-to-cell inflammatory and trophic signaling, are thought be viable therapeutic targets.

Keywords: exosomes, inhibitory neurons, mesenchymal stem cell, motor cortex, neuronal excitability, stroke

Abstract

Functional recovery after cortical injury, such as stroke, is associated with neural circuit reorganization, but the underlying mechanisms and efficacy of therapeutic interventions promoting neural plasticity in primates are not well understood. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles (MSC-EVs), which mediate cell-to-cell inflammatory and trophic signaling, are thought be viable therapeutic targets. We recently showed, in aged female rhesus monkeys, that systemic administration of MSC-EVs enhances recovery of function after injury of the primary motor cortex, likely through enhancing plasticity in perilesional motor and premotor cortices. Here, using in vitro whole-cell patch-clamp recording and intracellular filling in acute slices of ventral premotor cortex (vPMC) from rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) of either sex, we demonstrate that MSC-EVs reduce injury-related physiological and morphologic changes in perilesional layer 3 pyramidal neurons. At 14-16 weeks after injury, vPMC neurons from both vehicle- and EV-treated lesioned monkeys exhibited significant hyperexcitability and predominance of inhibitory synaptic currents, compared with neurons from nonlesioned control brains. However, compared with vehicle-treated monkeys, neurons from EV-treated monkeys showed lower firing rates, greater spike frequency adaptation, and excitatory:inhibitory ratio. Further, EV treatment was associated with greater apical dendritic branching complexity, spine density, and inhibition, indicative of enhanced dendritic plasticity and filtering of signals integrated at the soma. Importantly, the degree of EV-mediated reduction of injury-related pathology in vPMC was significantly correlated with measures of behavioral recovery. These data show that EV treatment dampens injury-related hyperexcitability and restores excitatory:inhibitory balance in vPMC, thereby normalizing activity within cortical networks for motor function.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Neuronal plasticity can facilitate recovery of function after cortical injury, but the underlying mechanisms and efficacy of therapeutic interventions promoting this plasticity in primates are not well understood. Our recent work has shown that intravenous infusions of mesenchymal-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) that are involved in cell-to-cell inflammatory and trophic signaling can enhance recovery of motor function after injury in monkey primary motor cortex. This study shows that this EV-mediated enhancement of recovery is associated with amelioration of injury-related hyperexcitability and restoration of excitatory-inhibitory balance in perilesional ventral premotor cortex. These findings demonstrate the efficacy of mesenchymal EVs as a therapeutic to reduce injury-related pathologic changes in the physiology and structure of premotor pyramidal neurons and support recovery of function.

Introduction

The pathogenesis of cortical injury, such as stroke, and how changes in neuronal circuits after injury can support recovery of function is complex and multifaceted. The acute phase of cortical injury is associated with neuronal dystrophy and inflammation that lead to alterations in membrane conductances, synaptic dysfunction, and excitotoxicity (for review, see Wang et al., 2007; Brouns and De Deyn, 2009; Carmichael, 2012; Lai et al., 2014; Anrather and Iadecola, 2016; Jayaraj et al., 2019). Subsequently, anti-inflammatory and trophic factors are upregulated (Kaushal and Schlichter, 2008) to promote neurite regrowth (Jones and Schallert, 1992; S. Li and Carmichael, 2006; Buga et al., 2008), synaptic remodeling (Stroemer et al., 1998; Benowitz and Carmichael, 2010), and compensatory changes in excitability, in an attempt to restore cortical function (for review, see Miyaiet al., 2002; Jang et al., 2003; Ward, 2004; Dancause et al., 2005; S. Li and Carmichael, 2006). However, chronic excitotoxity and inflammation exacerbates neuronal damage, impairs cortical reorganization, and prevents full recovery (Kaushal and Schlichter, 2008; Carmichael, 2012; Kohman and Rhodes, 2013; Jayaraj et al., 2019). Recovery can thus be facilitated by limiting acute damage and inflammation, and promoting neuronal plasticity (Chavez et al., 2009; Lakhan et al., 2009; Lambertsen et al., 2019), but underlying mechanisms, especially in primates, are unknown.

The immune regulation of neuronal plasticity after injury is largely mediated by signaling between neurons, and central and peripheral immune cells, such as microglia and T cells (for review, see Y. Wu et al., 2015; Yshii et al., 2015; Colonna and Butovsky, 2017; Lannes et al., 2017; Szepesi et al., 2018; Veiga-Fernandes and Artis, 2018; Thurgur and Pinteaux, 2019). One potential therapeutic that is thought to modulate neuroimmune signaling is extracellular vesicles (EVs), which are endosome-derived spheroids that transport nucleic acids and proteins between cells and are highly implicated in models of injury and neurodegeneration (for review, see Chivet et al., 2012; Di Trapani et al., 2016; Z. G. Zhang and Chopp, 2016; DeLeo and Ikezu, 2018; Munir et al., 2018; Reza-Zaldivar et al., 2018; Ruppert et al., 2018; Shanmuganathan et al., 2018; van Niel et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2018; Saeedi et al., 2019; Z. G. Zhang et al., 2019). In our rhesus monkey model of cortical injury, we demonstrated the efficacy of EVs derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) to enhance recovery of function following damage in the primary motor cortex (M1). EV-treated monkeys exhibited recovery to preinjury fine motor function by 3-5 weeks after treatment. In contrast, vehicle-treated monkeys reached a plateau, with incomplete functional recovery 8-12 weeks after injury (Moore et al., 2019).

In the current study, we investigated the neural basis of this EV-mediated enhancement of recovery by assessing injury-related biophysical and structural changes in pyramidal neurons in perilesional ventral premotor cortex (vPMC) of the monkeys from Moore et al. (2019), using in vitro whole-cell patch-clamp recording, intracellular filling, and immunohistochemistry. Specifically, we investigated layer 3 pyramidal neurons, which are thought to be involved in corticocortical pathways that modulate movement-related activity and undergo plasticity after injury (for review, see Johansen-Berg et al., 2002; Miyai et al., 2002; Carmichael, 2003, 2006; Dancause et al., 2005; Fregni and Pascual-Leone, 2006; S. Li and Carmichael, 2006; Darling et al., 2011; Nishimura and Isa, 2012). Our previous study has shown that motor task-related upregulation of c-fos, an activity-dependent intermediate early gene marker, in vPMC neurons is correlated with recovery of function in monkeys (Orczykowski et al., 2018). We provide evidence that injury to M1 induces hyperexcitability and enhances inhibition in perilesional vPMC neurons, to presumably compensate for damage and restore function, albeit not to the degree of an intact normal network. EV treatment appears to ameliorate these injury-related changes and restore excitatory:inhibitory (E:I) network balance in vPMC to support a greater degree of functional recovery.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Brain tissue used in this study was from 13 aged rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) of either sex, ranging from 16 to 26 years old (∼48-78 human years) (Tigges et al., 1988). Monkeys were acquired from nationalprimate research facilities with complete health records, and were housed individually in the Laboratory Animal Science Center at Boston University School of Medicine, which is fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. All procedures were approved by the Boston University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were conducted in accordance with the guidelines established by the National Institutes of Health's Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals.

MSC-EVs were extracted from MSCs harvested from the bone marrow of a young female adult monkey in our colony, as described previously (Moore et al., 2019). Tissue for experiments was obtained from 3 aged nonlesioned monkeys (female, age 17 y; female, age 19 y; male, age 20 y) that had no induced injury, and from 10 aged lesioned monkeys (female, ages 16–26 y old) randomly assigned to a treatment group before receiving a targeted cortical injury in the hand representation of the M1, as described in detail in our previous study (Moore et al., 2019). Five of these aged lesioned monkeys received vehicle (PBS) and five received EV treatment (see Fig. 1A). All personnel were blinded to groups for all procedures and experiments.

Figure 1.

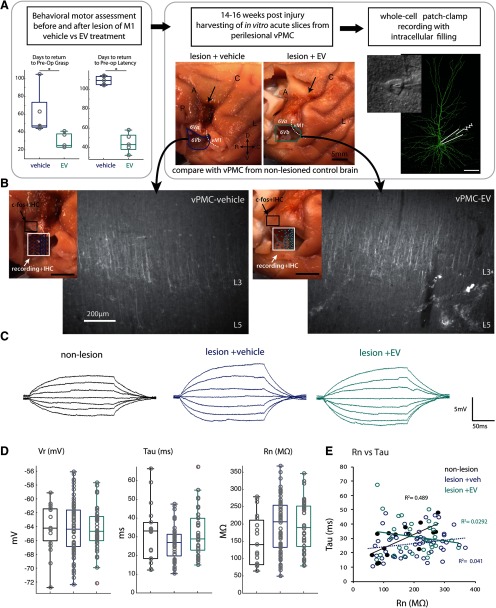

Experimental design and measurement of passive membrane properties of vPMC pyramidal neurons. A, Experimental workflow: Monkeys were first behaviorally assessed using our HDT (left panel) before and after cortical injury (arrow, middle panel), as described previously (Moore et al., 2019). The monkeys were randomly assigned to receive either vehicle or EV treatment, and then the rate and degree of behavioral recovery of preoperative grasp pattern and latency were assessed. Recovery data (adapted from Moore et al., 2019) show the number of days to recover, which was fewer (faster rate) in EV compared with vehicle-treated monkeys (t test, p < 0.01). At 14-16 weeks after injury, acute slices were harvested during perfusion with Kreb's buffer from vPMC (vPMCveh vs vPMCEV). Location of tissue block harvested containing vPMC (area 6Vb) immediately ventral to the lesion (A, arrow) and the estimated boundary between vPMC (area 6Va and 6Vb) and ventral M1 (vM1) are shown on the lateral surface of rhesus monkey brain. Whole-cell patch-clamp recording and intracellular filling of layer 3 vPMCveh (n = 69 neurons from 4 monkeys) and vPMCEV (n = 39 neurons from 2 monkeys) neurons were employed. Data from vPMC were compared with neurons harvested from vPMC of nonlesionedaged-matched control brains (vPMCnonlesioned; n = 22 neurons from 2 monkeys) from a cohort of monkeys in a separate study. B, Lateral surface of brain maps (left insets) shows the sampling location and 2D plots of recorded cells (white box), and sampling location of tissue analyzed for c-fos labeling experiments (black box; n = 5 EV-treated, n = 5 vehicle-treated monkeys). Representative epifluorescence images (right panels) show coronal vPMC slices from which recordings were obtained, which were labeled with SMI-32+ after fixation to verify cytoarchitecture. Note the strong band of SMI32+ label in layer 3 (L3) and 5 (L5). The absence of large SMI32+ Betz cells in L5 is consistent with the cytoarchitecture of vPMC. C, Representative traces of voltage responses to a series of 200 ms current pulses. D, Box-and-whisker and vertical scatter plots of Vr, taum, and Rn. E, Within-group linear relationships of membrane tau versus Rn.

Electrophysiological mapping of M1 hand area, surgical lesion, and treatment administration

After preoperative testing on the Hand Dexterity Task (HDT), surgical procedures to localize and lesion the hand area of M1 were conducted under aseptic conditions, as described previously (Moore et al., 2019). Briefly, each monkey was sedated with ketamine hydrochloride (10 mg/kg, i.m.) and anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (15-25 mg/kg, i.v.) to effect. The head was stabilized in a stereotactic apparatus and, after skin incision and reflection of the temporalis muscle, a bone flap (∼40 mm, anterior to posterior extent; ∼35 mm, medial to lateral extent) centered over the frontal and parietal lobes was removed. The dura was incised to expose the central sulcus and primary motor cortex. Electrical stimulation to evoke movements was delivered systematically across a grid of sites along the entire extent of the precentral gyrus, using a monopolar silver ball surface electrode (1 mm diameter). Stimulation grid sites were spaced 2 mm apart. Monopolar stimulus pulses of 250 µs duration at amplitudes from 2.0 to 3.0 mA were delivered at each site once every 2 s, first as a single pulse and then in a short train of four pulses at 100 Hz. During each stimulation, a trained observer noted muscle movements (e.g., distinct movement or twitches of muscle) in specific areas of the digits, hand, forearm, or arm, both visually and by palpation. The intensity of the motor response in the hand and digits was graded on a scale of 1–3 (barely visible to maximal). Stimulation sites with the lowest threshold and largest motor response were marked on the calibrated photograph, creating a cortical surface map of the hand area, where the lesion was localized. Cortical injury was induced by making a small incision in the pia at the dorsal limit of the mapped representation, and a small glass suction pipette was then inserted under the pia to bluntly transect the small penetrating arterioles. After the lesion was made, the dura was closed, the bone flap was sutured back in place, and the muscles, fascia, and skin were closed in layers. Immediately following surgery, antibiotics and analgesics were administered, and the monkey was monitored continuously until fully awake and able to eat and drink.

EVs were extracted from MSCs harvested from the bone marrow of a young female adult monkey in our colony that is part of our other studies on anatomic pathways, as described previously (Moore et al., 2019). The MSC-EV treatment doses were prepared at Henry Ford, according to well-established protocols in rodents and porcine animal models (Xin et al., 2013), and then were shipped back to Boston University School of Medicine on ice. The EV treatment, diluted4 × 1011 particles/kg in 10 ml of PBS or vehicle treatment (PBS), was administered intravenously to each randomly assigned monkey (while sedated with ketamine hydrochloride 10 mg/kg, i.m.), 24 h and again 14 d after cortical injury. Postoperative testing on the HDT began 2 weeks after surgery and continued for 12 weeks, as described previously (Moore et al., 2019).

Perfusion and preparation of acute slices

At ∼14-16 weeks after injury, monkeys were perfused using our two-stage Krebs-PFA perfusion method for harvesting live tissue and subsequent fixation (Amatrudo et al., 2012; Estrada et al., 2017). The animals were initially sedated with ketamine hydrochloride (10 mg/ml) and deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (to effect, 15 mg/kg, i.v.), then perfused through the ascending aorta first with 1-4 L of ice-cold Krebs-Henseleit buffer (in mM as follows: 6.4 Na2HPO4, 1.4 Na2PO4, 137 NaCl, 2.7 KCl, 5 glucose, 0.3 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, pH 7.4). Within 5 min of opening of the chest cavity (anoxia), a block of tissue (1 cm3), which included the caudal ventral premotor (area 6Vb (Barbas and Pandya, 1987; Morecraft et al., 2004) or area F4 (Matelli and Luppino, 1996; Rizzolatti et al., 1998)) and motor cortices, was harvested immediately below the lesion (Fig. 1A,B). We estimated the stereotactic location of the tissue block to be harvested from each monkey using gross landmarks based on the electrophysiological motor map we recorded during the lesion surgery (Moore et al., 2019). This block was transferred to oxygenated (95% O2, 5% CO2) ice-cold Ringer's solution (in mM as follows: 26 NaHCO3, 124 NaCl, 2 KCl, 3 KH2PO4, 10 glucose, 1.3 MgCl2, pH 7.4), and sectioned into 300 µm coronal acute slices with a vibrating microtome. To ensure that each block contained mainly vPMC, ∼2-3 mm from the caudal end of each block containing M1 was trimmed off and flash-frozen for biochemical analyses. The block was then mounted caudal side down on the vibratome stage to cut coronal slices through vPMC. Slices for recording were immediately placed into room temperature Ringer's solution and equilibrated for 1 h. To keep track of the rostrocaudal level (distance from the central sulcus) of the slices, every fifth 300 µm coronal slice was immediately fixed in 4% PFA for verification of cytoarchitectonic boundaries. Once fresh tissue harvesting was concluded, perfusate was switched to freshly depolymerized 4% PFA in 0.1 M PB (pH 7.4, at 37°C) to fix the intact whole brain. The whole fixed brain sample was blocked in situ in the coronal plane and then removed from the skull, cryoprotected in a series of glycerol solutions, and flash-frozen in −70°C isopentane (Rosene et al., 1986). The brain was cut on a freezing microtome in the coronal plane at 30 or 60 μm. Sections were stored in cryoprotectant (15% glycerol, in 0.1 M PB, pH 7.4) at −80°C until use (Estrada et al., 2017).

Whole-cell patch-clamp recording and assessment of electrophysiological properties

After a 1 h equilibration period, living acute slices were placed into submersion-type recording chambers (Harvard Apparatus), mounted on the stages of Nikon EDC infrared-differential interference contrast microscopes. All physiological experiments were conducted at room temperature, in oxygenated Ringer's solution (superfused at 2–2.5 ml/min), which improves the viability and duration of recordings from monkey acute slices. Standard tight-seal, whole-cell patch-clamp recordings with simultaneous biocytin filling were obtained from layer 3 pyramidal cells as described previously (Chang et al., 2005; Amatrudo et al., 2012; Medalla and Luebke, 2015; Medalla et al., 2017). Patch electrodes fabricated on a horizontal Flaming and Brown micropipette puller (Model P-87, Sutter Instruments) were filled with potassium methanesulfonate-based internal solution (in mM as follows: 122 KCH3SO3, 2 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, 10 NaHEPES, with 0.5% biocytin, pH 7.4), with resistances of 3-6 MΩ in the external Ringer's solution. Data were acquired using EPC-9 or EPC-10 patch-clamp amplifiers using PatchMaster software (HEKA Elektronik). The series resistance ranged from 10 to 15 MΩ and was not compensated. Bessel filter frequency was 10 kHz, and sampling frequency was at 7 kHz for voltage-clamp and 12 kHz for current-clamp recordings.

Cell inclusion criteria for electrophysiological analyses were as follows: resting membrane potential (Vr) ≤ −55 mV, stable access resistance, action potential (AP) overshoot, and repetitive firing responses (Amatrudo et al., 2012). To measure passive membrane properties (Vr; input resistance, Rn; and passive membrane time constant, tau) a series of 200 ms depolarizing and hyperpolarizing current steps was used, as described previously (Chang et al., 2005; Amatrudo et al., 2012; Medalla and Luebke, 2015; Medalla et al., 2017). Rn was calculated as the slope of the best-fit line of the voltage-current linear relationship. tau was assessed by fitting a single exponential function to the membrane potential response to a −10 pA hyperpolarizing current step. Single AP firing properties (threshold, amplitude, rise time, fall time, and duration at half-maximal amplitude) were measured from the second AP in a train of three or more spikes generated by the smallest current step in the series. Rheobase was determined as the minimum current required to evoke a single AP during a 10 s depolarizing current ramp (0-200 pA). A series of 2 s hyperpolarizing and depolarizing current steps (−170 to 380 pA, using either 20 or 50 pA increments) was used to assess active and repetitive firing properties. Traces were exported to MATLAB (The MathWorks) to assess AP firing and adaptation properties. Interspike intervals (ISIs) between individual spikes in each 2 s train were measured and used to calculate firing frequency adaptation (FFA) properties, as described previously (Zaitsev et al., 2012). The rate of initial and late FFA was measured at the 2 s current step closest to 1.5× rheobase. The first and second instantaneous frequencies (f1 and f2) were calculated as the reciprocals of the first and second ISIs (f1 = 1/ISI1; f2 = 1/ISI2), respectively. Steady-state firing frequencies (fss) were calculated as the reciprocal of the average ISIs within the last quarter of the current step. Initial (FFAinitial) and late (FFAlate) FFA were calculated as the percent decrease in frequency between f1 and f2, and between f1 and fss, respectively. To assess the relationship between FFA and input current, an adaptation ratio between the first and last ISI was calculated for each current step.

Spontaneous excitatory (EPSCs) and inhibitory (IPSCs) postsynaptic currents recorded for a minimum of 2 min at a holding potential of −80 mV and −40 mV, respectively (Medalla et al., 2017). Analyses of synaptic event data were performed using MiniAnalysis software (Synaptosoft), with event detection threshold set at maximum root mean squared noise level (5 pA). Recordings of synaptic events were assessed for frequency, mean amplitude, area under the curve, and kinetics (rise and decay time, and half-width).

Immunohistochemical (IHC) labeling procedures on 300 µm slices

Processing of filled neurons and IHC labeling of vesicular GABAergic transporter (VGAT)

To visualize recorded cells filled with biocytin, 300 µm slices were fixed for 48 h in 4% PFA in 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4, then rinsed and incubated for 2 h in 1% Triton X (in 0.1 M PBS), followed by 48 h in streptavidin-Alexa 488 (1:500 in 0.1 M PBS; Invitrogen). To assess inhibitory terminals apposed to filled neurons, slices were incubated in 50 mm glycine (2 h at room temperature), then in 10 mm sodium citrate antigen retrieval buffer (pH. 8.4, at 60°C-70°C), and preblocked (5% normal donkey serum and 5% BSA with 0.1% Triton-X; 2 h at room temperature) as described previously (Medalla and Luebke, 2015; Medalla et al., 2017). All antibodies were diluted in 1% normal donkey serum, 0.2% acetylated BSA (BSA-c, Aurion), and 0.1% Triton-X in 0.1 M PB. Slices were incubated in the primary antibody against VGAT (1:400, guinea pig polyclonal, Synaptic Systems, catalog #131004; RRID:AB_887873) for over 7 d at 4°C, with 8 × 10 min 150 W microwave sessions at 35°C (Biowave, Ted Pella) to assist in antibody penetration. Slices were incubated in donkey anti-guinea pig F(ab′)2 IgG conjugated to Alexa-647 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) for 4 d (at 4°C, with 4 × 10 min 150 W, 35°C microwave).

IHC labeling of SMI-32 for cytoarchitectural verification of recorded slices

To verify the area of recording, a subset of serial coronal slices collected across the rostral to caudal extent of the block were resectioned to 100 µm and immunolabeled for SMI32, a nonphosphorylated neurofilament cytoskeletal protein that labels pyramidal neurons in layers 3 and 5 (Campbell and Morrison, 1989) (see Fig. 1B). SMI32 is a marker used to delineate cytoarchitectonic areas, which is especially useful to identify the large layer 5 Betz cells present in primary motor cortex (Campbell and Morrison, 1989; Preuss et al., 1997; Gabernet et al., 1999; Garcia-Cabezas and Barbas, 2014). Slices were incubated in the primary antibody against SMI32 (1:1000 mouse monoclonal, Biolegend; RRID:AB_10719742), followed by an incubation in donkey anti-mouse Alexa-405 F(ab′)2 IgG (as above).

For all IHC labeling experiments, slices were mounted on glass slides and coverslipped with Prolong antifade medium (Invitrogen). Control experiments wherein the primary antibody was omitted showed no labeling.

IHC labeling of c-fos activated task-related neurons and inhibitory neuron markers

Quadruple-immunofluorescence labeling was used to assess the distribution of c-fos+ neurons, an immediate early gene transcription factor that peaks 1-4 h after neuronal activation begins (Dragunow and Faull, 1989; Rosene et al., 2004; for review, see Hoffman et al., 1993; Kovacs, 2008), therefore labeling neurons activated during a final motor HDT testing session before sacrifice and tissue harvesting (Orczykowski et al., 2018). We batch-processed two serial 30 µm coronal sections through vPMC (area 6Va/F5), from each lesioned monkey.

To assess cell-type specific task-related activation, sections were coincubated overnight in primary antibodies against c-fos (1:400, guinea pig polyclonal, Synaptic Systems, catalog #226005; RRID:AB_2800522), parvalbumin (PV) (1:1000, goat polyclonal, Swant, catalog #PVG213; RRID:AB_2721207), calbindin (CB) (1:1000, mouse monoclonal, Swant, catalog #300; RRID:AB_10000347), and calretinin (CR) (1:2000, rabbit polyclonal, Swant, catalog #CR7696; RRID:AB_2619710). Sections were then coincubated overnight (4°C) in the following secondary antibodies raised in donkey (1:200): anti-guinea pig 488 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), anti-goat 546 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), anti-rabbit 633 (Invitrogen), and biotinylated anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) followed by Streptavidin 405 (1:200 Invitrogen; overnight 4°C).

IHC to assess dendritic structure

To assess dendritic integrity and damage, 30 µm sections through vPMC (area 6Va/F5) were immunolabeled for the microtubule-associated protein-2 (MAP2; 1:2000, chicken polyclonal, Abcam, RRID:AB_2138153), a marker for apical dendrites of pyramidal neurons (Caceres et al., 1984; Peters and Sethares, 1991). Sections were then incubated in donkey anti-chicken Alexa-488 F(ab′)2 IgG (as above). After IHC procedures, 30 µm sections were mounted on gelatin-coated glass slides and coverslipped with Prolong antifade medium (Invitrogen). Control experiments wherein the primary antibody was omitted showed no labeling.

Verification of rostrocaudal slice level and location of recorded neurons

To map the location of recorded neurons, the distance of each slice from the central sulcus was estimated based on the location of the harvested block, and the series of slices harvested along the rostrocaudal extent of each block, and subsequently resectioned and labeled with SMI-32 (above). The caudal-most coronal slice in this SMI-32 series was estimated to be ∼2 mm from the central sulcus and was used as the reference to calculate the relative distances of the subsequent serial slices. Each slice with a recorded cell was then matched to a slice within this reference SMI-32 series to estimate the distance of each recorded cell from the central sulcus, and plot the estimated cell location on a 2D map (see Fig. 1B).

Post hoc verification of the regional and laminar location of each recorded cell was used by measuring soma-to-pia distances from images of recording electrodes, and cytoarchitectural verification using matched sections stained with SMI-32. A slice within vPMC was identified based on published cytoarchitectonic criteria (Preuss et al., 1997; Gabernet et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2002; Boussaoud et al., 2005; for review, see Belmalih et al., 2007), particularly by the absence of large Betz cells in layer 5, which are prominent in M1. These Betz cells are very large pyramidal neurons with multiple primary dendrites emanating along the perimeter of the soma (for review, see Belmalih et al., 2007; Garcia-Cabezas and Barbas, 2014). Neurons verified to be recorded in a vPMC slice and localized in layer 3 (soma to pia distance between 350-850 µm) were included in the dataset.

Recorded neurons were verified to be located in caudal vPMC, corresponding to area 6Vb of the cytoarchitectural maps of (Barbas and Pandya, 1987; Morecraft et al., 2004, 2019) and area F4 of the functional maps of (Matelli and Luppino, 1996; Rizzolatti et al., 1998). This specific subdivision of vPMC has overlapping proximal forelimb and orofacial representations, as described previously (Graziano et al., 2002; Graziano and Aflalo, 2007; Kaas et al., 2012), and as verified in the motor maps from these monkeys (Moore et al., 2019).

Confocal imaging and analyses of pyramidal neuron morphology

Neurons with complete somata and dendrites with no cut branches in the proximal third of the apical tree were selected for confocal imaging using a Leica SPE confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems). All image stacks were deconvolved using AutoQuant (Media Cybernetics). Dendritic arbors of whole cells imaged at 0.3 × 0.3 × 0.3 µm per voxel (40×/1.3 NA oil-immersion; 488 nm) were reconstructed using NeuronStudio (Rodriguez et al., 2006) (RRID:SCR_013798), according to our established protocols (Amatrudo et al., 2012; Medalla et al., 2017).

For assessment of filled spines and appositions of filled neurons with VGAT+ boutons, a second series of image stacks were acquired via 2-channel confocal imaging at a resolution of 0.04 × 0.04 × 0.3 µm per voxel (63×/1.4 NA oil-immersion objective and 488 and 647 nm diode lasers), as described previously (Medalla et al., 2017). For each neuron, confocal stacks were acquired to image the soma, one complete basilar dendritic branch, and the main apical trunk followed to the end of one complete distal apical dendritic branch. Image stacks were deconvolved (as above), and tiled and analyzed using Neurolucida 360 (RRID:SCR_016788; MBF Bioscience). Spines along the imaged dendrite were counted and classified into subtypes according to previous criteria (Medalla and Luebke, 2015; Medalla et al., 2017) as follows: thin (head width < 0.6 µm); mushroom (head width ≥ 0.6); stubby (no neck); and filopodia (neck length > 3 µm). Densities of total spines and of each subtype were calculated as the number of spines per micron of dendritic length.

Appositions between the neurons and VGAT+ puncta were classified as follows: apposed to dendritic shafts; spine head or neck of each subtype; or somata. An apposition was identified as a spatial overlap between the saturated red and green signal >2 pixels in the x-y, >2 optical slices in the z for thin dendrites and axons, or >4 optical slices in the z for highly saturated somata, as described previously (Medalla et al., 2017). Appositions on dendritic shafts and spines were expressed as the number per micron of dendritic length. Appositions on somata were expressed as number per surface area of somata. Profiles of somata were automatically traced section-by-section, and surface area was calculated by the Neurolucida software as a series of cylindrical sections capped by the end profiles. Sholl analyses with concentric spheres placed at 20 μm increments from the center of the soma were used to determine dendritic parameters of apical and basal arbors, and the spine and VGAT apposition density as a function of distance from the center of the soma (Sholl, 1953).

Cell counting of c-fos+ labeled inhibitory neurons

To assess the density of c-fos+ neurons co-labeled with inhibitory markers (CB, PV, or CR), 4-channel confocal image stacks were acquired from 30 µm sections (20×, 0.8 NA; 0.3 × 0.3 × 1 µm per voxel; Zeiss 710, Carl Zeiss). Four fields, spaced 500 µm apart, were randomly sampled in layer 3 of the subregion of vPMC located dorsal and rostral to the fresh tissue biopsy from each monkey (see Fig. 1B). This vPMC subregion corresponded to area 6Va of (Barbas and Pandya, 1987; Morecraft et al., 2004, 2019), area F5 of (Matelli and Luppino, 1996; Rizzolatti et al., 1998), and “hand and digit/grasp” area PMv of (Dum and Strick, 2002) and (Kaas et al., 2012). A z stack from the top to the bottom of the tissue was captured in each field. In each z stack, single- and double-labeled cells were counted using the FIJI cell counter (https://imagej.net/Fiji; 1997-2016; RRID:SCR_002285) (Schindelin et al., 2012), adapting stereological counting rules (Fiala and Harris, 2001).

Quantification of the density of MAP2+-labeled dendrites

To assess the density of MAP2+-labeled dendrites on 30 µm sections, two columns through L1-L3 of vPMC (area 6Va/F5), spaced 200 µm apart, were imaged using a Leica SPE confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems) at high resolution (0.1 × 0.1 × 0.3 µm; 40× oil-immersion 1.3 NA objective), and deconvolved as described above. The optical density of MAP2+ labeling was quantified using particle analyses in ImageJ/FIJI, as described previously (Medalla et al., 2017). The signal threshold for the analyses was automatically set in the first L1 field, and then applied to subsequent fields within the same section. The total percent area covered by MAP2+ label and the average size of individual MAP2+-labeled pixels were calculated for each field. The average measures of all the fields was calculated for each monkey and compared between the two treatment groups.

Experimental design and statistics

All data are expressed as box-and-whisker plots or vertical scatter plots, together with tabulated mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were conducted in MATLAB (R2018, RRID:SCR_001622). Outcome measures of pyramidal neuron properties were compared between cells from multiple animals in each group using multifactorial ANOVAs with post hoc Fisher's LSD in MATLAB. For pairwise comparisons of cfos+ cell densities between treatment groups, Student's t test was used. We recorded and compared a total of 130 neurons from vPMC (area 6Vb/F4; vPMCnonlesion, n = 22 neurons from 2 monkeys; vPMCveh, n= 69 from 4 monkeys; vPMCEV, n = 39 from 2 monkeys) and reconstructed and compared a total of 47 neurons (vPMCnonlesion, n = 15 neurons from 2 monkeys; vPMCveh, n = 17 from 4 monkeys; and vPMCEV, n = 15 from 2 monkeys) layer 3 pyramidal neurons. Animal was included as an independent variable and showed no significant main effect in any outcome measure. Sex was compared within the nonlesion group and showed no significant differences in any outcome measure; thus, the data were pooled.

Measurements of c-fos+ cell densities (CB, PV, and CR) in vPMC (area 6Va/F5) were compared between monkeys of the two treatment groups (n = 5 vehicle vs n = 5 EV-treated female monkeys). Relationships between outcome variables were determined using linear regression analyses. Power analyses show that, for outcome measures in this study, tests can detect an effect size of at least f = 0.46 at a significance level of 0.05 with 80% power. Because of the limitation of the number of subjects in the experimental cohort, we cannot investigate the independent effect of sex on all the conditions and variables.

Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) was performed to analyze similarities among individual neurons in the experimental groups, based on three sets of electrophysiological outcome measures as follows: passive (tau, Rn, Vr); active (rheobase, AP threshold, AP amplitude, AP rise time, AP fall time, AP duration, depolarizing sag potential, AP firing frequency response to 20, 40, 60, and 80 pA injections, initial and late FFA); synaptic (EPSC and IPSC frequency, amplitude, rise time, decay time, area, half-width and total charge, E:I ratio) properties. For each set of outcome measures, z scores were obtained for each variable, and pairwise comparisons were used to calculate a distance matrix based on squared Euclidean distances. The multidimensional distance matrix was then reduced to two dimensions via NMDS, and the resulting values of each neuron were plotted, with the distances between data points representing the relative similarities based on the set of variables.

One-way multivariate ANOVA (MANOVA) was used to compare the relative degree of influence each neuronal electrophysiological outcome measure contributes to the separation of the three experimental groups (nonlesioned control, lesion + vehicle, lesion + EV). Only outcome measures with significant differences based on ANOVA were included for the analysis. Outcome measures included in the MANOVA are as follows: rheobase; AP threshold; AP amplitude; AP rise time; AP fall time; AP duration; AP firing frequency response to 20, 40, 60, and80 pA current injections; initial and late FFA; EPSC amplitude; EPSC frequency; EPSC total charge; IPSC frequency; and E:I ratio. The z scores were obtained for each of the measured outcome variables, and two canonical variables (weighted linear sums of all individual outcome variables) that best separate out the three experimental groups were computed. For each canonical variable, the absolute value of the coefficient for each outcome measure represents the degree of influence that specific measure contributes to the separation of the groups, with higher absolute values representing a greater influence.

Results

Lesion-related changes in active membrane properties of vPMC pyramidal neurons are consistent with hyperexcitability

The excitability and signaling properties of pyramidal neurons are governed by passive intrinsic membrane properties and an assortment of ion channels mediating active conductances (for review, see Spruston, 2008). In this study, we assessed lesion-associated changes in the biophysical and structural properties of layer 3 pyramidal neurons in vPMC, after injury in the hand representation of M1 (Fig. 1A). Layer 3 vPMC pyramidal neurons mediate corticocortical pathways (for review, see Callaway, 2002; Barbas, 2015) that are thought to reorganize after M1 injury to promote recovery of function (e.g., Carmichael, 2003; Ward, 2004; Kantak et al., 2012). The monkeys were first trained on our HDT and then underwent surgery to induce cortical damage in the hand representation of M1, as described previously (Moore et al., 2019). Monkeys then received infusions of MSC EVs or vehicle (PBS) intravenously 24 h and again 14 d after the cortical injury. Postoperative testing on the HDT began 2 weeks after surgery and continued for 12 weeks. As reported in our previous study, EV-treated monkeys exhibited significantly faster recovery rates (fewer days to full recovery) of preoperative grasp pattern and latency to retrieve than vehicle-treated monkeys (Fig. 1A, left; data adapted from Moore et al., 2019). Following the completion of postoperative testing, at ∼14-16 weeks after injury, live acute slices of vPMC were harvested from all monkeys during perfusion with aCSF (Kreb's buffer) for whole-cell patch-clamp recordings and intracellular filling of layer 3 pyramidal neurons (Fig. 1A, right). The location of each recorded neuron relative to central sulcus was estimated and mapped (Fig. 1B, insets, white boxes). ROI in vPMC was histologically verified for each block using SMI-32 labeling, a cytoarchitectural marker for a subset of L3 and L5 pyramidal neurons that delineates M1 and PMC based on previous cytoarchitectonic criteria (Preuss et al., 1997; Gabernet et al., 1999; Liu et al., 2002; Boussaoud et al., 2005; Belmalih et al., 2007). Specifically, vPMC is marked by the absence of Betz cells, the very large pyramidal neurons in L5 with multiple primary dendrites emanating from the soma, which are predominant in M1 (for review, see Belmalih et al., 2007; Garcia-Cabezas and Barbas, 2014) (Fig. 1B). Mapping and histologic analyses verified that recorded neurons were located in caudal vPMC, corresponding to the area 6Vb or area F4, involved in both forelimb and orofacial movements (Matelli and Luppino, 1996; Rizzolatti et al., 1998; Graziano et al., 2002; Morecraft et al., 2004, 2019; Graziano and Aflalo, 2007). We compared properties of vPMC neurons from nonlesioned control brains (vPMCnonlesion, n = 22 neurons from 2 monkeys) and lesioned brains with either vehicle (vPMCveh, n = 69 neurons from 4 monkeys) or EV (vPMCEV, n = 39 neurons from 2 monkeys) treatment.

Intrinsic passive membrane properties (Vr, tau, and Rn) of pyramidal neurons were not significantly different across groups (ANOVA, main effect p > 0.05 for all comparisons; Fig. 1C,D; Table 1). In contrast, significant lesion-related differences in single AP properties of vPMC neurons, consistent with hyperexcitability, were found. In vPMC neurons from both lesion groups, APs exhibited faster kinetics (ANOVA main effect: faster rise, p = 0.0001; fall, p = 0.0008; duration, p = 0.0002) compared with neurons in the nonlesion control group (Fisher's LSD post hoc, p < 0.04 for all comparisons; Fig. 2A,B). However, post hoc comparisons between treatment groups showed that vPMCEV neurons exhibited slower rise times (EV vs veh, p = 0.02) and greater amplitude (EV vs veh, p = 0.009) than vPMCveh neurons.

Table 1.

Electrophysiological properties of vPMC layer 3 pyramidal neurons

| Nonlesion | Vehicle | EV | ANOVA | Nonlesionversus vehicle | EV versusnonlesion | EV versusvehicle | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passive membrane properties | |||||||

| Membrane tau (ms) | 32.0 ± 3.56 | 26.7 ± 1.32 | 31.9 ± 2.20 | 0.089 | 0.103 | 0.965 | 0.053 |

| Rn (MΩ) | 152.0 ± 16.56 | 195.2 ± 9.79 | 196.9 ± 11.88 | 0.073 | 0.031 | 0.037 | 0.912 |

| Resting potential (mV) | −64.0 ± 0.78 | −64.3 ± 0.48 | −64.4±0.50 | 0.940 | 0.770 | 0.728 | 0.916 |

| Active membrane properties | |||||||

| AP threshold | −34.3 ± 1.36 | −39.0 ± 0.62 | −37.2 ± 0.79 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.040 | 0.093 |

| AP amplitude (mV) | 65.2 ± 2.28 | 71.3 ± 1.08 | 68.5 ± 1.64 | 0.025 | 0.009 | 0.193 | 0.145 |

| AP rise time (ms) | 1.2 ± 0.05 | 1.0 ± 0.02 | 1.1 ± 0.04 | 0.0001 | <0.001 | 0.034 | 0.024 |

| AP fall time (ms) | 3.4 ± 0.17 | 2.8 ± 0.10 | 2.6 ± 0.08 | 0.001 | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.282 |

| AP duration at half-maximum (ms) | 2.3 ± 0.09 | 1.9 ± 0.06 | 1.9 ± 0.05 | 0.000 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.824 |

| Medium AHP (mV) | −10.4 ± 0.53 | −10.4 ± 0.31 | −10.7 ± 0.33 | 0.788 | 0.895 | 0.726 | 0.493 |

| sAHP (mV) | −2.7 ± 0.39 | −1.8 ± 0.10 | −2.0 ± 0.09 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.005 | 0.350 |

| Rheobase (pA) | 119.2 ± 9.20 | 86.3 ± 6.11 | 89.1 ± 6.07 | 0.013 | 0.004 | 0.015 | 0.761 |

| Sag potential (mV) | −5.4 ± 0.68 | −3.9 ± 0.30 | −3.7 ± 0.45 | 0.051 | 0.032 | 0.020 | 0.607 |

| FFA | |||||||

| FFA ratio (initial) | 0.36 ± 0.04 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.26 ± 0.03 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.023 | 0.275 |

| FFA ratio (late) | 0.58 ± 0.04 | 0.49 ± 0.02 | 0.54 ± 0.03 | 0.048 | 0.023 | 0.362 | 0.111 |

| Synaptic current properties | |||||||

| EPSC frequency (Hz) | 4.90 ± 0.56 | 2.13 ± 0.25 | 2.83 ± 0.22 | <0.00001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.084 |

| EPSC amplitude (pA) | 9.43 ± 0.45 | 10.75 ± 0.36 | 9.72 ± 0.44 | 0.063 | 0.046 | 0.681 | 0.065 |

| EPSC rise time (ms) | 3.11 ± 0.09 | 3.17 ± 0.14 | 3.26 ± 0.08 | 0.772 | 0.782 | 0.499 | 0.594 |

| EPSC decay time (ms) | 4.29 ± 0.16 | 4.16 ± 0.25 | 4.24 ± 0.17 | 0.937 | 0.743 | 0.907 | 0.809 |

| EPSC half-width (ms) | 4.36 ± 0.23 | 4.05 ± 0.21 | 4.23 ± 0.17 | 0.624 | 0.367 | 0.734 | 0.529 |

| EPSC area (pAms) | 45.5 ± 3.3 | 47.8 ± 3.4 | 46.0 ± 3.3 | 0.885 | 0.671 | 0.925 | 0.705 |

| IPSC frequency (Hz) | 0.43 ± 0.05 | 1.23 ± 0.20 | 1.23 ± 0.23 | 0.048 | 0.019 | 0.032 | 0.994 |

| IPSC amplitude (pA) | 19.0 ± 1.5 | 19.6 ± 0.8 | 17.4 ± 1.4 | 0.330 | 0.724 | 0.406 | 0.138 |

| IPSC rise time (ms) | 4.90 ± 0.17 | 4.62 ± 0.12 | 4.91 ± 0.15 | 0.248 | 0.225 | 0.976 | 0.145 |

| IPSC decay time (ms) | 13.3 ± 1.2 | 11.2 ± 0.7 | 13.3 ± 1.1 | 0.142 | 0.135 | 0.961 | 0.092 |

| IPSC half-width (ms) | 10.9 ± 1.0 | 9.2 ± 0.5 | 10.9 ± 1.0 | 0.125 | 0.127 | 0.986 | 0.079 |

| IPSC area (pAms) | 245.8 ± 20.1 | 240.5 ± 17.4 | 224.4 ± 14.8 | 0.754 | 0.859 | 0.515 | 0.520 |

| EPSC total charge | 219.3 ± 26.4 | 97.2 ± 12.2 | 115.2 ± 11.9 | 0.000004 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.383 |

| IPSC total charge | 110.8 ± 15.7 | 294.6 ± 56.2 | 339.5 ± 77.1 | 0.097 | 0.068 | 0.038 | 0.599 |

| E:I ratio | 3.11 ± 0.64 | 0.65 ± 0.12 | 1.58 ± 0.34 | 0.00002 | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.037 |

Figure 2.

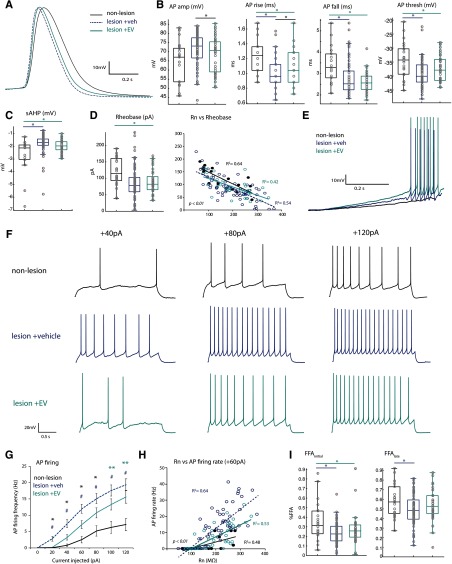

AP firing properties of vPMC pyramidal neurons are altered by lesion and EV treatment A, Representative single AP waveforms from the three groups, superimposed, showing differences in AP kinetics (rise, fall, duration at half-maximum amplitude). B, Box-and-whisker and vertical scatter plots of individual data points of single AP properties: amplitude (ANOVA Fisher's LSD post hoc, EV vs veh, p = 0.009), rise (veh vs nonlesion, p = 0.03; EV vs nonlesion, p = 0.00004; EV vs veh, p = 0.02), fall (veh vs nonlesion, p = 0.0003; EV vs nonlesion, p = 0.002), and threshold (veh vs nonlesion, p = 0.0003; EV vs nonlesion, p = 0.04). C, Amplitude of sAHP (veh vs nonlesion, p = 0.0002; EV vs nonlesion, p = 0.005). D, Box-and-whisker and vertical scatter plots (left) of rheobase current, and linear relationships of rheobase versus Rn (right, p < 0.01 for all correlations). E, Representative voltage responses to a low-amplitude current ramp stimulus in vPMCveh and vPMCEV neurons; the vPMCnonlesion neuron did not fire APs at this current ramp stimulus. F, Representative voltage traces showing steady-state AP firing in response to 2 s current steps at 40, 80, 120 pA. G, Mean AP firing rates in response to a series of depolarizing current steps (Fisher's LSD post hoc, 20, 40, 60, 80 pA: *veh vs EV, p < 0.04; #veh vs nonlesion, p < 0.009; 100, 120 pA: #veh vs nonlesion, p < 0.0002; **EV vs nonlesion, p < 0.03). H, Linear relationships of Rn and firing rate at lower current steps (60 pA; p < 0.01). Slopes significantly different between groups at all steps (40, 60, 80, 120: veh vs EV, p < 0.001; veh vs nonlesion, p < 0.048). I, Box-and-whisker and vertical scatter plots of percent initial and late FFA (Fisher's LSD post hoc: % FFAinitial, veh vs nonlesion, p = 0.0009; EV vs nonlesion, p = 0.02; % FFAlate veh vs nonlesion p = 0.02).

Further, neurons from both lesion groups had significantly lower AP firing thresholds (ANOVA main effect, p = 0.001; Fisher's LSD post hoc veh vs nonlesion, p = 0.0003; EV vs nonlesion, p = 0.04; Fig. 2A,B), and a smaller slow afterhyperpolarization (sAHP) compared with vPMCnonlesion neurons (ANOVA main effect, p = 0.001; veh vs nonlesion, p = 0.0002; EV vs nonlesion, p = 0.005; Fig. 2C). Similarly, rheobase, the minimum current to elicit an AP, was significantly lower in vPMC neurons from the two lesion groups compared with those in the nonlesion control group (ANOVA main effect, p = 0.01; veh vs nonlesion, p = 0.003; EV vs nonlesion, p = 0.015; Fig. 2D,E). For all three groups, rheobase exhibited significant linear relationships with Rn, which was expected, as the same current injection elicits higher voltage responses in neurons with higher Rn. However, pairwise comparisons of linear regressions with experimental group as an additional response variable revealed that the slope of linear regression was significantly greater for vPMCnonlesion neurons compared with that of vPMCveh neurons (p = 0.025). In contrast, the slope of linear regression did not differ between vPMCEV and the two other groups (vs nonlesion, p = 0.053; vs veh, p = 0.49). These results indicate that lesion-associated changes in excitability cannot be explained by passive properties alone. Further, these results suggest that cortical lesion alters active conductances that, in turn, lead to more rapid AP firing kinetics and greater excitability in perilesional vPMC neurons.

Lesion-related increase in repetitive AP firing rate is reduced by EV treatment

vPMCveh and vPMCEV neurons both exhibited greater repetitive AP firing rates in response to 2 s current injections compared with control vPMCnonlesion neurons (ANOVA main effect, p < 0.03 for all significantly different comparisons; Fig. 2F,G). However, at low-amplitude current injections, vPMCEV neurons exhibited significantly lower firing rates than vPMCveh (ANOVA, Fisher's LSD post hoc, 20, 40, 60, 80 pA; p = 0.002, 0.0058, 0.0078, 0.038; Fig. 2F,G). While firing rates exhibited significant linear relationships to Rn (Fig. 2H), the slope of linear regression in vPMCveh neurons was significantly steeper than in the other groups (40, 60, 80, 120 pA: veh vs EV, p = 0.001, 0.0002, 0.0004, 0.005; veh vs nonlesion = 0.048, 0.003, 0.0005, 0.009), while vPMCEV did not differ from vPMCnonlesion neurons.

We assessed whether higher AP firing rates were due to reduced FFA in neurons from nonlesioned versus lesioned brains (Fig. 2I). The FFAinitial, percentage decrease from onset to second instantaneous firing frequency ((f1 – f2)/f1), was reduced in lesion groups compared with nonlesion control (ANOVA, main effect, p = 0.004; veh vs nonlesion, p = 0.0009; EV vs nonlesion, p = 0.02; Fig. 2I). However, FFAlate, percentage decrease from onset to steady-state frequency ((f1 – fss)/f1), was only reduced compared with vPMCnonlesion neurons in vPMCveh neurons, and not in vPMCEV neurons (ANOVA, main effect, p = 0.048; Fisher's LSD post hoc, veh vs nonlesion, p = 0.02; Fig. 2I). Thus, EV treatment appears to reduce lesion-related hyperexcitability in vPMC neurons, in part by increasing FFAlate adaptation, and therefore lowering AP firing rates.

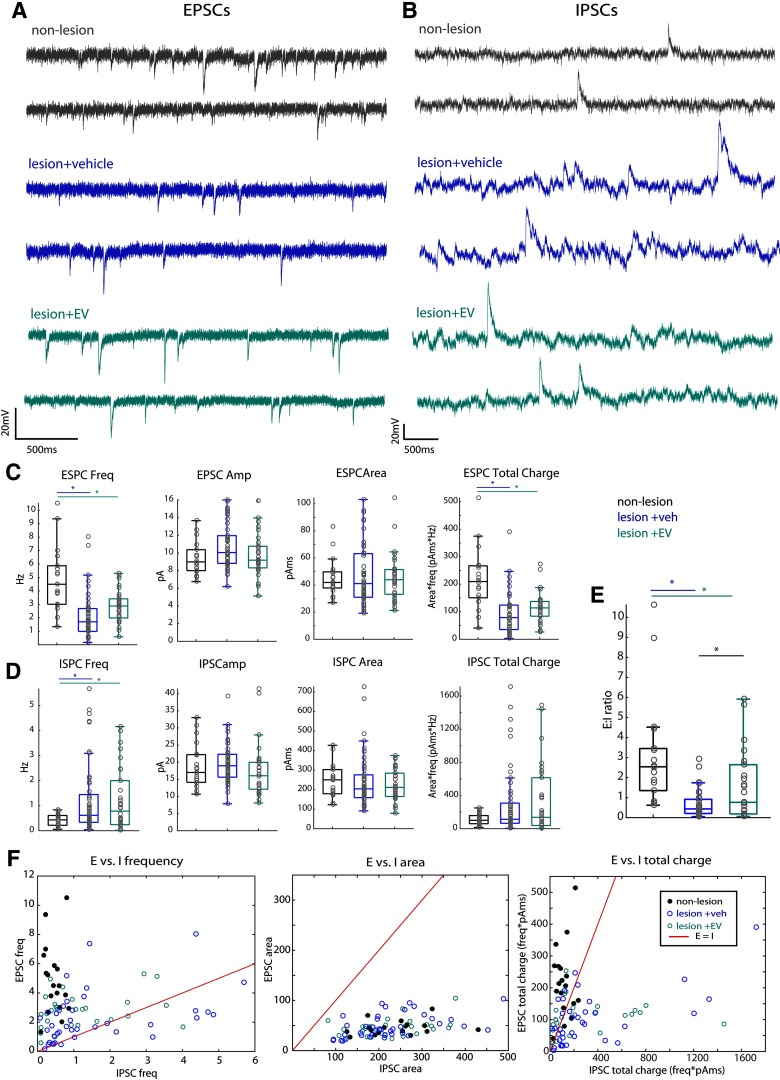

EV treatment is associated with greater E:I synaptic current ratio

In addition to membrane biophysical properties, network excitability and output of pyramidal neurons are shaped by excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs (for review, see Spruston, 2008). Thus, we compared the properties of EPSCs and IPSCs of vPMCnonlesion (n of neurons: n =18 EPSC, n = 19 IPSC, from 2 monkeys), vPMCveh (n = 37 EPSC, n = 44 IPSC from 4 monkeys), and vPMCEV (n = 30 EPSC, n = 30 IPSC from 2 monkeys) neurons.

vPMCveh and vPMCEV neurons from lesion brains showed significantly lower EPSC frequency compared with vPMCnonlesion neurons (ANOVA main effect, p = 0.00000052; Fisher's LSD post hoc, veh vs nonlesion, p = 0.0000001; EV vs nonlesion = 0.0001; Fig. 3A,C; Table 1). In contrast, IPSC frequency was greater in vPMC neurons from lesioned versus nonlesioned brains (ANOVA main effect, p = 0.048, Fig. 3B,D; Table 1). Both vPMCveh (ANOVA, Fisher's LSD post hoc, p = 0.019) and vPMCEV neurons (p = 0.032) exhibited ∼3× increase in IPSC frequency relative to vPMCnonlesion neurons, without differences in IPSC amplitude and kinetics (Fig. 3B,D). However, while no statistical differences between the treatment groups were found for both EPSC and IPSC properties, the measured values for vPMCEV neurons were consistently intermediate to vPMCveh neurons and vPMCnonlesion neurons. Thus, we calculated the ratio of total excitatory to inhibitory charge transfer (E:I ratio) and found significant effects of both lesion and treatment. The E:I ratio was significantly lower in neurons from both lesion groups compared with vPMCnonlesion neurons (ANOVA main effect, p = 0.000016; Fisher's LSD post hoc, veh vs nonlesion, p = 0.000003; EV vs nonlesion, p = 0.004). However, this lesion-related difference was less pronounced in PMCEV compared with vPMCveh neurons (Fig. 3E). vPMCEV neurons had significantly greater E:I ratio compared with vPMCveh neurons (Fisher's LSD post hoc, p = 0.037). In both vPMCEV and vPMCnonlesion neurons, E:I ratios were > 1, indicative of a predominance of excitation over inhibition (Fig. 3E). In contrast, mean E:I ratio of vPMCveh neurons was < 1, hence showing a predominance of inhibition over excitation. Scatter plots of EPSC versus IPSC properties showed that vPMCnonlesion neurons and the majority of the vPMCEV neurons were scattered on the left side of the line representing E = I frequency and total charge (Fig. 3F). In contrast, vPMCveh neurons were scattered closer to the E = I line, with a substantial population scattered on the right side, dominated by inhibition (Fig. 3F, blue circles, left, right). These data suggest an overdominance of inhibition occurs after cortical injury, but EV treatment restores normative E:I balance in perilesional vPMC neurons.

Figure 3.

Reduced EPSCs and increased IPSCs in perilesional vPMC neurons. A, Representative traces of ESPCs (Vhold -80 mV) recorded in voltage clamp from vPMCnonlesion (n = 18 neurons from 2 monkeys), vPMCveh (n = 37 from 4 monkeys), and vPMCEV (n = 30 from 2 monkeys) layer 3 pyramidal neurons. B, Representative traces of IPSCs (Vhold -40 mV) recorded in voltage clamp from vPMCnonlesion (n = 19 neurons from 2 monkeys), vPMCveh (n = 44 from 4 monkeys), and vPMCEV (n =30 from 2 monkeys) layer 3 pyramidal neurons. C, Box-and-whisker plots and vertical scatter plots of individual cells of EPSC properties: ESPC frequency (ANOVA Fisher's LSD post hoc, veh vs nonlesion, p = 0.0000001; EV vs nonlesion = 0.0001), EPSC amplitude, EPSC area, and EPSC total charge (frequency × area; Fisher's LSD post hoc, veh vs nonlesion, p = 0.00,008; EV vs nonlesion = 0.000001). D, Box-and-whisker plots and vertical scatter plots of individual cells of ISPC properties: IPSC frequency (Fisher's LSD post hoc, veh vs nonlesion, p = 0.019; EV vs nonlesion, p = 0.032), IPSC amplitude, IPSC area, and IPSC total charge (frequency × area). E, The estimated E:I ratio based on the frequency and mean area of each cell (Fisher's LSD post hoc, veh vs nonlesion, p = 0.000003; EV vs nonlesion, p = 0.004; EV vs veh p = 0.037). F, Scatter plots showing the relative distribution of neurons from each group based on the relationship of excitatory and inhibitory properties: frequency, area, and total charge. Red line in each plot indicates the linear relationship where E = I. EPSC total charge dominates IPSC total charge in vPMCnonlesion neurons, mainly due to E-I difference in frequency. vPMCveh neurons exhibit a significant proportion with greater IPSC frequency and total charge than EPSC. Compared with vPMCveh neurons, vPMCEV neurons are distributed closer to vPMCnonlesion, with most neurons exhibiting greater excitatory than inhibitory tone, some scattered close to the E = I line, and very few below the E = I line.

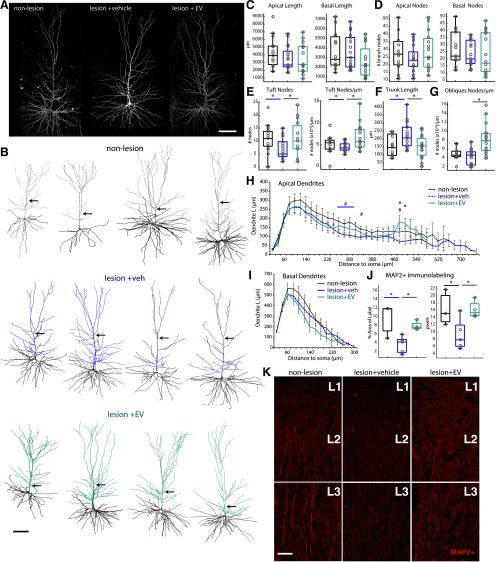

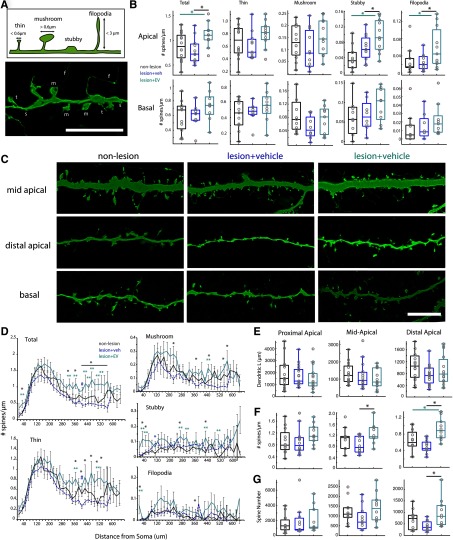

EV treatment is associated with greater apical dendritic complexity and MAP2+ expression

Plasticity after injury integrally involves dendritic remodeling and synapse turnover in surviving neural circuits (Brown et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2008; Gao et al., 2011; Ueno et al., 2012; for review, see Xiong et al., 2019). Thus, the effects of lesion and EV treatment on dendritic branching topology were assessed in vPMCEV (n = 15 neurons from 2 monkeys), vPMCveh (n = 17 from 4 monkeys), and vPMCnonlesion (n = 15 neurons from 2 monkeys) pyramidal neurons intracellularly filled during recording (Fig. 4A,B). No significant differences were found among groups with regards to mean total dendritic length, branch nodes, and extents (Fig. 4C,D; Table 2). However, apical dendritic tufts exhibited significant lesion- and treatment-related changes (ANOVA main effect: number of nodes, p = 0.045; nodes/µm, p = 0.0097). Specifically, vPMCveh neurons from vehicle-treated lesioned monkeys had less complex apical tuftscompared with control nonlesion monkeys, with significantly lower number of apical tuft branch nodes compared with vPMCnonlesion control neurons (Fisher's LSD post hoc; p = 0.04; Fig. 4E). However, this lesion-related reduction of apical tuft complexity was ameliorated in EV-treated monkeys, with vPMCEV neurons not significantly different from nonlesion control monkeys. Importantly, vPMCEV neurons exhibited a significantly greater number (Fisher's LSD post hoc; p = 0.03) and density (p = 0.003) of branch nodes in apical tufts compared with vPMCveh neurons (Fig. 4E). Further, Sholl analyses revealed a significant peak in dendritic length within distal apical segments, 480-500 µm from the soma (ANOVA main effect, p = 0.003, 0.01) of vPMCEV neurons relative to vPMCveh (Fisher's LSD post hoc, p = 0.001, 0.0072) and vPMCnonlesion neurons (Fisher's LSD post hoc, p = 0.028, 0.04; Fig. 4H). Interestingly, vPMCEV neurons also exhibited significantly shorter main apical trunk lengths (ANOVA main effect, p = 0.015; Fisher's LSD post hoc veh vs EV, p = 0.01; Fig. 4F) and more complex apical obliques (ANOVA main effect, p = 0.00007; number of nodes/µm; p = 0.00003; Fig. 4G) compared with vPMCvehneurons. Basal arbors were similar in topology, length, and extents among groups (Fig. 4C,D,I; Table 2). These data show that EV treatment is associated with an elaboration of apical tuft and oblique compartments of vPMC pyramidal neurons after lesion in M1, indicative of recovery-associated dendritic remodeling. Thus, we assessed whether these changes in dendritic arbor complexity are also associated with differences in MAP2, a microtubule-associated protein known to be destabilized and altered after neuronal injury (Dawson and Hallenbeck, 1996; Y. Li et al., 1998; G. L. Li et al., 2000). Optical density of analyses revealed a significantly lower density (percent area labeled; ANOVA main effect, p = 0.01) and smaller size (pixel area, ANOVA main effect, p = 0.039) of MAP2+ immunolabeling in layers 1-3 of perilesional vPMC (area 6Va/F5) in vehicle-treated lesioned monkeys (n = 5 monkeys) compared with both EV-treated lesioned (n = 4 monkeys; Fisher's LSD post hoc % area, p = 0.02; average size, p = 0.03) and nonlesioned control monkeys (n = 3 monkeys; Fisher's LSD post hoc % area, p = 0.006, average size, p = 0.026; Fig. 4J,K). In contrast, EV-treated monkeys exhibited no significant differences in MAP2+ labeling in vPMC compared with nonlesioned control monkeys. These data suggest that EV treatment either reduced initial dendritic damage or stimulated dendritic remodeling in vPMC after cortical injury in M1.

Figure 4.

EV treatment increases apical dendrite complexity and MAP2 expression in perilesional vPMC. A, x–y maximum projections of confocal image stacks of representative L3 vPMC pyramidal neurons. B, Representative 3D reconstructions of vPMCnonlesion (n = 15 neurons from 2 monkeys), vPMCveh (n = 17 from 4 monkeys), and vPMCEV (n = 15 from 2 monkeys) layer 3 pyramidal neurons. Note the point where the main apical trunk branches into an apical tuft. C–G, Box-and-whisker plots and vertical scatter plots of dendritic morphologic outcome measures of individual neurons: (C) apical and basal dendritic length and (D) branch nodes; (E) morphologic properties of apical tufts: apical tuft branch nodes and nodes/length. F, Main apical trunk length. G, Apical oblique dendrites nodes/length. H, Sholl analyses of mean apical dendritic length length (ANOVA main effect, 280, 480, 500 µm, p = 0.029, 0.003, 0.01; Fisher's LSD post hoc: *EV vs veh, p < 0.013; #veh vs nonlesion, p < 0.04). I, Sholl analyses of mean basal dendritic length. J, Box-and-whisker plots and vertical scatter plots of percent area labeled and average particle size of MAP2+ immunolabel in vPMC. Multiple comparisons were done between animals (lesion EV-treated, n = 4; lesion vehicle-treated, n = 5; nonlesion control, n = 3; ANOVA Fisher LSD post hoc, p < 0.05). K, Maximum projection of confocal image stacks showing MAP2+ immunolabel in layers 1 (L1), 2 (L2), and 3 (L3) of vPMC. Scale bars: A, B, K, 100 µm.

Table 2.

Morphologic properties of vPMC layer 3 pyramidal neurons

| Nonlesion | Vehicle | EV | ANOVA | Nonlesionversus vehicle | EV versusnonlesion | EV versusvehicle | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apical dendritic morphology | |||||||

| Dendritic length (µm) | 4308.8 ± 525.9 | 3542.2 ± 389.7 | 3471.7 ± 509.5 | 0.375 | 0.913 | 0.238 | 0.212 |

| No. of nodes | 28.1 ± 3.1 | 24.4 ± 2.1 | 29.1 ± 3.2 | 0.417 | 0.218 | 0.322 | 0.811 |

| Vertical extent (µm) | 497.8 ± 34.6 | 551.9 ± 29.1 | 433.3 ± 41.2 | 0.055 | 0.017 | 0.254 | 0.190 |

| Tuft Hor extent (µm) | 243.2 ± 11.4 | 183.6 ± 22.1 | 199.8 ± 20.9 | 0.065 | 0.535 | 0.024 | 0.105 |

| Obliques Hor extent (µm) | 283.9 ± 28.7 | 298.1 ± 22.1 | 230.5 ± 29.1 | 0.165 | 0.070 | 0.693 | 0.155 |

| Proximal apical L (µm) | 1944.6 ± 327.0 | 1714.8 ± 202.5 | 1544.3 ± 265.4 | 0.564 | 0.631 | 0.518 | 0.289 |

| Mid apical L (µm) | 1321.4 ± 161.9 | 1138.3 ± 165.6 | 1021.3 ± 265.4 | 0.436 | 0.598 | 0.410 | 0.204 |

| Distal apical L (µm) | 1042.0 ± 121.3 | 745.4 ± 75.2 | 904.3 ± 135.3 | 0.139 | 0.285 | 0.049 | 0.380 |

| No. of obliques | 7.7 ± 1.0 | 8.4 ± 0.6 | 6.6 ± 0.7 | 0.217 | 0.083 | 0.478 | 0.304 |

| Obliques length (µm) | 2105.7 ± 412.5 | 1783.4 ± 235.0 | 1498.7 ± 299.1 | 0.400 | 0.512 | 0.458 | 0.178 |

| Obliques no. of nodes | 9.9 ± 1.9 | 8.2 ± 1.4 | 10.5 ± 2.0 | 0.612 | 0.342 | 0.499 | 0.788 |

| Obliques no. of nodes/µm | 0.0050 ± 0.0004 | 0.0044 ± 0.0005 | 0.0083 ± 0.0009 | 0.00007 | 0.00003 | 0.444 | 0.001 |

| Trunk length (µm) | 153.1 ± 17.6 | 219.8 ± 19.8 | 151.9 ± 19.2 | 0.015 | 0.012 | 0.013 | 0.963 |

| Tuft length (µm) | 2017.5 ± 214.3 | 1511.3 ± 204.8 | 1788.9 ± 297.5 | 0.305 | 0.398 | 0.127 | 0.499 |

| Tuft no. of nodes | 10.7 ± 1.4 | 11.1 ± 1.7 | 6.8 ± 1.0 | 0.045 | 0.027 | 0.040 | 0.864 |

| Tuft no. of nodes/µm | 0.0051 ± 0.0005 | 0.0044 ± 0.0003 | 0.0068 ± 0.0008 | 0.010 | 0.003 | 0.360 | 0.036 |

| Basal dendritic morphology | |||||||

| Dendritic length (µm) | 3676.7 ± 493.7 | 3595.4 ± 432.6 | 2608.5 ± 410.8 | 0.162 | 0.107 | 0.895 | 0.091 |

| No. of nodes | 27.3 ± 3.2 | 23.6 ± 2.2 | 23.2 ± 3.7 | 0.574 | 0.912 | 0.387 | 0.338 |

| Vertical extent (µm) | 237.9 ± 21.2 | 259.8 ± 20.1 | 204.0 ± 18.0 | 0.135 | 0.047 | 0.417 | 0.241 |

| Horizontal extent (µm) | 347.0 ± 24.9 | 317.7 ± 27.1 | 276.6 ± 25.8 | 0.180 | 0.258 | 0.409 | 0.066 |

| Proximal basal L (µm) | 1629.2 ± 242.9 | 1399.6 ± 184.3 | 1099.2 ± 169.1 | 0.209 | 0.294 | 0.407 | 0.079 |

| Mid basal L (µm) | 1654.3 ± 218.6 | 1412.3 ± 205.6 | 1192.5 ± 190.0 | 0.364 | 0.513 | 0.397 | 0.159 |

| Distal basal L (µm) | 407.6 ± 76.4 | 434.2 ± 79.2 | 366.9 ± 74.6 | 0.867 | 0.596 | 0.805 | 0.788 |

| Spine density (no. of spines/µm length) | |||||||

| Proximal apical | 0.928 ± 0.126 | 0.916 ± 0.130 | 1.162 ± 0.112 | 0.294 | 0.162 | 0.946 | 0.181 |

| Mid apical | 1.050 ± 0.114 | 0.835 ± 0.091 | 1.243 ± 0.122 | 0.034 | 0.010 | 0.141 | 0.204 |

| Distal apical | 0.639 ± 0.079 | 0.492 ± 0.046 | 0.918 ± 0.088 | 0.001 | 0.0002 | 0.130 | 0.008 |

| Proximal basal | 0.487 ± 0.090 | 0.369 ± 0.073 | 0.408 ± 0.091 | 0.591 | 0.765 | 0.332 | 0.496 |

| Mid basal | 0.789 ± 0.102 | 0.692 ± 0.108 | 0.864 ± 0.136 | 0.589 | 0.309 | 0.538 | 0.623 |

| Distal basal | 0.651 ± 0.066 | 0.696 ± 0.104 | 1.014 ± 0.207 | 0.085 | 0.085 | 0.786 | 0.034 |

| VGAT appositions (no. of appositions/µm length) | |||||||

| Proximal apical shaft | 0.228 ± 0.047 | 0.130 ± 0.043 | 0.303 ± 0.059 | 0.049 | 0.016 | 0.140 | 0.273 |

| Mid apical shaft | 0.160 ± 0.022 | 0.075 ± 0.026 | 0.166 ± 0.018 | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 0.867 |

| Distal apical shaft | 0.129 ± 0.028 | 0.050 ± 0.014 | 0.184 ± 0.040 | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.038 | 0.161 |

| Proximal apical spine | 0.045 ± 0.010 | 0.056 ± 0.018 | 0.134 ± 0.040 | 0.022 | 0.023 | 0.713 | 0.010 |

| Mid apical spine | 0.068 ± 0.011 | 0.044 ± 0.012 | 0.121 ± 0.048 | 0.110 | 0.039 | 0.482 | 0.151 |

| Distal apical spine | 0.045 ± 0.010 | 0.027 ± 0.005 | 0.070 ± 0.024 | 0.095 | 0.031 | 0.337 | 0.195 |

| Proximal basal shaft | 0.156 ± 0.025 | 0.145 ± 0.028 | 0.139 ± 0.015 | 0.473 | 0.234 | 0.424 | 0.674 |

| Mid basal shaft | 0.112 ± 0.020 | 0.139 ± 0.037 | 0.116 ± 0.015 | 0.032 | 0.017 | 0.030 | 0.765 |

| Distal basal shaft | 0.102 ± 0.016 | 0.149 ± 0.045 | 0.194 ± 0.045 | 0.024 | 0.007 | 0.137 | 0.166 |

| Proximal basal spine | 0.032 ± 0.007 | 0.019 ± 0.012 | 0.040 ± 0.008 | 0.169 | 0.167 | 0.641 | 0.071 |

| Mid basal spine | 0.047 ± 0.009 | 0.078 ± 0.023 | 0.094 ± 0.016 | 0.128 | 0.048 | 0.501 | 0.172 |

| Distal basal spine | 0.061 ± 0.009 | 0.070 ± 0.030 | 0.120 ± 0.043 | 0.096 | 0.034 | 0.453 | 0.149 |

EV treatment is associated with greater excitatory and inhibitory inputs on apical dendrites

Consistent with an elaboration of apical dendrites, we found significantly greater mean densities of dendritic spines, the major sites of excitatory inputs, specifically on apical dendrites of vPMCEV neurons (n = 11 neurons from 2 monkeys) compared with vPMCveh (n = 12 from 4 monkeys) and vPMCnonlesion neurons (n = 11 neurons from 2 monkeys; ANOVA main effect, p = 0.02; Fisher's LSD post hoc, EV vs veh p = 0.00962; EV vs nonlesion p = 0.049; Fig. 5A–C). This difference in apical spine density was mainly due to significantly greater densities of stubby spines (ANOVA main effect, p = 0.0016; Fisher's LSD post hoc EV vs veh, p = 0.04; vs nonlesion, p = 0.0004) and filopodia (ANOVA main effect, p = 0.04; Fisher's LSD post hoc EV vs veh, p = 0.02; vs nonlesion, p = 0.03) on vPMCEV neurons (Fig. 5B,C). Sholl analyses of spine density show that greater densities of spines on vPMCEV neurons were found mainly on middle to distal segments, ∼340-580 µm from the soma (ANOVA main effect, p < 0.04 for all significantly different comparisons; Fig. 5D). Interestingly, this pattern was consistent across all subtypes, except for stubby spines, which had the greater densities in both proximal (ANOVA main effect, 40, 60 µm; p = 0.007, 0.03), and distal (280, 440 µm; p = 0.038, 0.048) apical segments of vPMCEV neurons compared with vPMCveh (Fisher's LSD post hoc, 40, 60, 280, 440 µm; p = 0.003, 0.018, 0.019, 0.043) and vPMCnonlesion neurons (40, 60, 280, 440 µm; p = 0.007, 0.017, 0.032, 0.023; Fig. 5D). We further analyzed spine distribution by normalizing dendritic lengths for each neuron into proximal, middle, and distal apical thirds, and calculated spine density and extrapolated total spine numbers within each of these compartments (Fig. 5E–G). Consistent with Sholl analyses, we found greater total spine density on the middle (ANOVA main effect, p = 0.03) and distal third (p = 0.00061) compartments of apical dendrites of vPMCEV neurons compared with vPMCveh (Fisher's LSD post hoc EV vs veh: middle, p = 0.01; distal, p = 0.00,015) and vPMCnonlesion (EV vs nonlesion, distal, p = 0.008) neurons (Fig. 5F). A similar pattern was found for estimated spine number along the distal apical third compartment, with vPMCEV neurons exhibiting significantly greater spine number than vPMCveh neurons (ANOVA main effect, p = 0.021, Fisher's LSD post hoc EV vs veh, p = 0.006; EV vs nonlesion; Fig. 5G).

Figure 5.

EV treatment increases spine density on apical dendrites of perilesional vPMC neurons. A, Schematic of spine classification criteria (top) and representative confocal z-maximum projection image (bottom) of spine subtypes (t, Thin; m, mushroom; s, stubby; f, filopodia). B, Box-and-whisker and vertical scatter plots of spine density (total spines and by subtype) in apical and basal dendrites of individual vPMCnonlesion (n = 11 neurons from 2 monkeys), vPMCveh (n = 12 from 4 monkeys), and vPMCEV (n = 11 from 2 monkeys) layer 3 pyramidal neurons. C, Representative confocal z-maximum projection images of mid apical, distal apical, and basal dendritic segments. D, Sholl analyses of mean total spine density and spine density by subtype at each 20 µm incremental proximal to distal distance from the soma, along the extent of a subsampled apical dendritic segment from each neuron. Total spine density (ANOVA main effect, 40, 340, 380 µm, p < 0.03; 420-580 µm, p < 0.04; Fisher's LSD post hoc, *EV vs veh, p < 0.02; #veh vs nonlesion 420 µm, p = 0.03; **EV vs nonlesion, p < 0.045). Thin spine density (ANOVA main effect, 380, 420, 440, 480, 520, 540 µm, p < 0.04; Fisher's LSD post hoc, *EV vs veh, p < 0.01; #veh vs nonlesion 420 µm, p = 0.001; **EV vs nonlesion 380 520 µm, p = 0.017, 0.005). Stubby spine density (ANOVA main effect, 40, 60, 120, 280, 320, 440, 520 µm, p < 0.048; Fisher's LSD post hoc, *EV vs veh, p < 0.02; **EV vs nonlesion p < 0.03). Mushroom spine density (ANOVA main effect, 240, 380, 460, 560, 580 µm, p < 0.04; Fisher's LSD post hoc, *EV vs veh, p < 0.016; **EV vs nonlesion 460 µm, p = 0.04). Filopodia spine density (ANOVA main effect, 20, 380 µm, p < 0.03; Fisher's LSD post hoc. *EV vs veh, p < 0.02). E, Total dendritic length, (F) spine density, and (G) estimated spine number (total dendritic length × spine density) in the proximal, middle, and distal thirds of apical dendrites, normalized by total length. Scale bars: A, C, 10 µm.

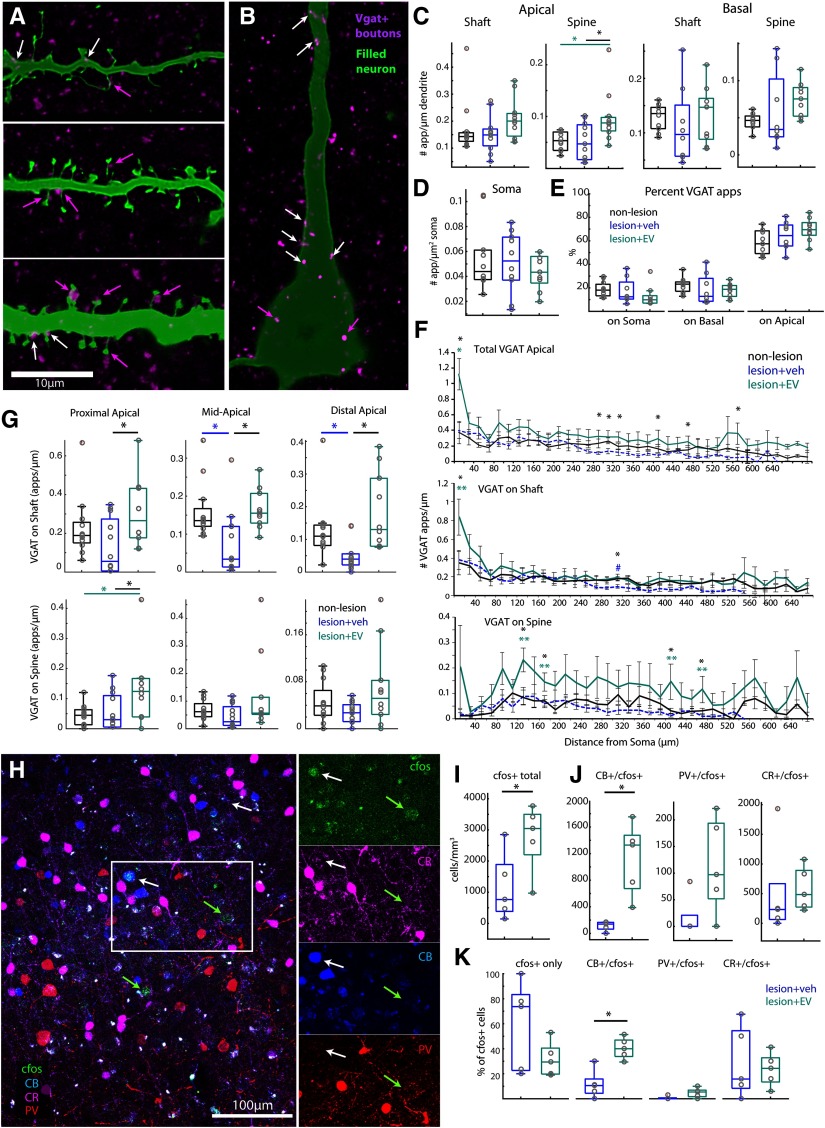

Consistent with greater apical spine densities, vPMCEVneurons also exhibited a significantly greater total density of VGAT+ appositions (putative inhibitory inputs) especially on apical dendritic spines (ANOVA main effect, p = 0.007) compared with vPMCveh (Fisher's LSD post hoc, p = 0.006) and vPMCnonlesion neurons (p = 0.006; Fig. 6A,C). Sholl analyses revealed that, compared with vPMCveh neurons, vPMCEV neurons exhibited significantly greater total densities of VGAT+ appositions within the most proximal 20 µm from the soma, and within the distal 300-480 µm from the soma (ANOVA main effect, 20, 300, 320, 340, 420, 480 µm; p = 0.001, 0.03, 0.02, 0.02, 0.04, 0.01; Fisher's LSD post hoc, EV vs veh, p = 0.001, 0.009, 0.008, 0.006, 0.01, 0.004; Fig. 6F, top). Further analyses of apical compartments normalized to total dendritic length showed that the proximal apical third of vPMCEV neurons exhibited a significantly greater density of VGAT+ appositions on spines (ANOVA main effect, p = 0.02) and shafts (ANOVA main effect, p = 0.049) compared with vPMCveh neurons (Fisher's LSD post hoc on spines, p = 0.02, on shaft p = 0.015; Fig. 6G; Table 2). Within the normalized middle and distal apical compartments, VGAT+ appositions on shafts were also significantly greater in vPMCEV neurons compared with vPMCveh neurons (ANOVA main effect, middle, p = 0.009; distal, p = 0.005; Fisher's LSD post hoc, EV vs veh middle, p = 0.007; distal, p = 0.001). In addition, vPMCveh neurons exhibited a significantly lower density of VGAT+ appositions on shafts within these segments compared with vPMCnonlesion control neurons (veh vs nonlesion middle, p = 0.008; distal, p = 0.04; Fig. 6G). These data are indicative of a lesion-related decrease in VGAT+ apposition density within middle-distal segments that are normalized in vPMCEV neurons, which did not differ significantly from control vPMCnonlesion neurons. In contrast to apical dendrites, where the majority of VGAT+ appositions are located (Fig. 6E), VGAT+ appositions on basal dendrites (Table 2) and somata did not differ across groups (Fig. 6B,D). These data show that EV treatment is associated with an upregulation of apical dendritic inhibition predominantly on spines, and an amelioration of lesion-related loss of VGAT+ input on middle-distal apical compartments, which can contribute to the filtering of increased excitatory input on vPMCEV neurons.

Figure 6.

Greater density of apical inhibitory inputs and c-fos+ activation of dendritic-targeting inhibitory neurons in EV-treated brains. A, B, Single confocal optical slice images showing representative VGAT+ appositions on dendritic shafts (A, white arrows), spines (A, magenta arrows), and somata (B, magenta arrows) of filled vPMCnonlesion (n = 11 neurons from 2 monkeys), vPMCveh (n = 12 from 4 monkeys), and vPMCEV (n =11 from 2 monkeys) layer 3 pyramidal neurons. C, D, Box-and-whisker plots and vertical scatter plots of individual data points showing the following: (C) density VGAT+ dendritic appositions on shafts and spines of subsampled apical and basal dendritic segments from each neuron; (D) density of VGAT+ appositions on somata; and (E) proportion of total VGAT appositions on somata, apical and basal dendrites. F, Sholl analyses showing the mean density of total VGAT+ dendritic appositions (ANOVA main effect, 20, 300, 320, 340, 420, 480 µm: p < 0.04; Fisher's LSD post hoc, *EV vs veh, p < 0.01) and mean density of VGAT+ appositions on shafts and spines at each 20 µm incremental proximal to distal distance from the soma, along the extent of a subsampled apical dendritic segment from each neuron (ANOVA main effect, shaft 20, 320 µm: p = 0.03, 0.014; Fisher's LSD post hoc, *EV vs veh, p < 0.02; **EV vs nonlesion, 20 µm, p = 0.013, #veh vs nonlesion, 320 µm, p = 0.02; ANOVA main effect, spines 140, 180, 420, 480 µm: p = 0.008, 0.03, 0.03, 0.02; Fisher's LSD post hoc, *EV vs veh, p < 0.01; **EV vs nonlesion, p < 0.04). G, Box-and-whisker and vertical scatter plots of individual data points showing mean density of VGAT+ appositions on normalized proximal, middle, and distal thirds of apical dendrites. H, Representative confocal z-maximum projection image stack showing co-labeling of CB, PV, and CR with c-fos in perilesional vPMC. Tissue was harvested 3 h after performance of the HDT to label the intermediate early gene, c-fos in vPMC, and quantify neuronal cell types presumably activated during the HDT (n = 5 EV-treated, n = 5 vehicle-treated monkeys). I, Total density of neurons labeled with c-fos+ in vPMC. J, Cell density and (K) proportion of subpopulations of c-fos+ neurons colabeled with calcium binding proteins, CB+, PV+, or CR+, expressed on inhibitory neurons in layers 2–3 of vPMC. Scale bars: A, B, 10 µm; H, 100 µm.

EV treatment is associated with greater c-fos+ activation of dendritic-targeting inhibitory neurons

Greater inhibitory inputs on apical dendrites, especially on spines, of vPMCEV neurons, suggest that the EV- and vehicle-treated lesion brains likely differ in inhibitory neurons expressing CR, PV, and CB, which target distinct somatodendritic compartments of pyramidal neurons (for review, see DeFelipe, 1997). Thus, in layers 2-3 of vPMC of vehicle-treated (n = 5) versus EV-treated (n = 5) lesion monkeys, we assessed the overlap of inhibitory cell markers with c-fos (Fig. 6G–J), an immediate early gene transcription factor that peaks 1-4 h after the onset of neuronal activation (Dragunow and Faull, 1989; Hoffman et al., 1993; Rosene et al., 2004; for review, see Kovacs, 2008). A previous study from our group showed that c-fos+ cells are upregulated in vPMC, 3 h after performance on the HDT, and is correlated with recovery of function (Orczykowski et al., 2018). Here we assessed c-fos expression in the dorsal-rostral part of vPMC (adjacent to the extracted biopsy), which corresponded to vPMC area 6Va of (Barbas and Pandya, 1987; Morecraft et al., 2004, 2019), area F5 of (Matelli and Luppino, 1996; Rizzolatti et al., 1998), and the “hand and grasp” area PMv of (Dum and Strick, 2002; Kaas et al., 2012), which is involved in hand movement (Fig. 1B).

While there were no differences in the density and proportion of PV+, CB+, or CR+ neurons between groups (data not shown) EV-treated brains exhibited a greater density of c-fos+ neurons in layers 2-3 of vPMC compared with vehicle-treated brains (n = 5 EV, n = 5 vehicle, paired t test, p = 0.047; Fig. 6H,I). The majority of these c-fos+ neurons were co-labeled with either CB+ or CR+, or were unlabeled for inhibitory markers, and were likely excitatory (Fig. 6H,K). There was a significantly greater density (t test, p = 0.0032; Fig. 6J) and proportion (p = 0.0019; Fig. 6K) of CB+/c-fos+ neurons in EV-treated compared with vehicle-treated monkeys (Fig. 6J,K). These findings show that, compared with vehicle-treated brains, EV-treated brains exhibited a greater degree of c-fos+ activation predominantly of distal dendrite and spine-targeting CB+ inhibitory neurons during the HDT.

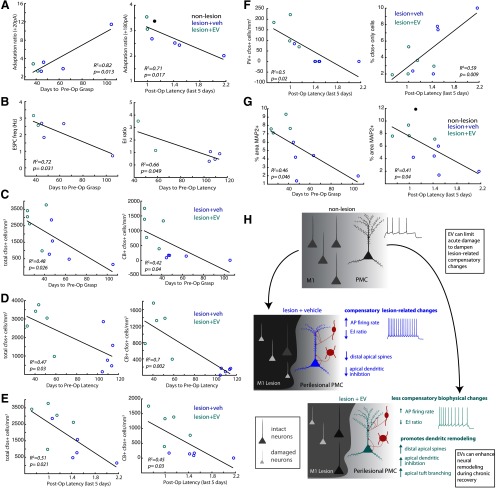

EV treatment is associated with a shift in vPMC pyramidal neuron properties toward a nonlesioned state

Our data revealed significant differences in layer 3 vPMC pyramidal neuron structure and function that are dependent on lesion and treatment. A consistent pattern for electrophysiological outcome variables is that measurements for EV-treated neurons consistently fell between measurements for vehicle-treated and nonlesioned neurons. Thus, we assessed the relative similarity and clustering of neurons in each group by conducting NMDS based on pairwise distance correlations across five sets of outcome measures, as described previously (Gilman et al., 2017) (Fig. 7A,B). The NMDS plot clusters data points based on a proximity distance matrix, such that points that are closer together are more similar with respect to a set of outcome measures (Hilgetag et al., 2016). NMDS plots based on active membrane and synaptic properties separated neurons belonging to vPMCveh, vPMCEV, and vPMCnonlesion groups into three clusters (Fig. 7A). Compared with vPMCveh neurons, vPMCEV neurons were more similar (closer proximity, smaller distance) to vPMCnonlesion control neurons (Fig. 7A). In contrast, no systematic NMDS clustering was observed based on passive membrane properties. NMDS plots based on dendritic morphologic and spine and VGAT distribution properties also clustered neurons into groups. However, in contrast to electrophysiological properties, these NMDS plots based on morphologic properties show clustering of vPMCnonlesion neurons in between vPMCEV and vPMCveh neurons. These data show that vPMCEV and vPMCveh neurons were more dissimilar to each other than to vPMCnonlesion neurons, which suggests divergent morphologic changes in neurons from the two treatment groups after lesion.

Figure 7.

EV treatment after lesion normalizes electrophysiological and morphological properties of vPMC neurons. A, NMDS plots showing clustering on neurons based on multiple passive membrane, active membrane, and synaptic current outcome variables. The proximity of points in each NMDS plots indicate the relative similarity-based pairwise correlation of multiple variables. B, NMDS plots showing clustering on neurons based on multiple dendritic morphologic properties, and spine and VGAT apposition distribution. C, Scatter plot based on MANOVA of active and synaptic current outcome measures that significantly predicted group membership. The MANOVA resulted in two significant canonical variables that separated the population into three distinct groups, based on a linear combination of the outcome measures. The first canonical variable separated the neurons in the nonlesioned control group from the lesioned groups (p = 0.0000064, eigen value = 2.2). The second canonical variable separated neurons based on treatment (vPMCveh vs vPMCEV; p = 0.04, eigen value = 0.67). Among the outcome measures, AP firing frequency and EPSC and IPSC frequencies were the strongest discriminators (i.e., greatest absolute value of the coefficients of the canonical variable) of membership of group membership (see Table 3). D, Scatter plot based on MANOVA of dendritic morphologic, spine, and VGAT apposition distribution properties. The MANOVA resulted in one significant canonical variable (p = 0.01, eigen value = 49.72) that separated the population into two distinct groups separating the vPMCveh neurons from vPMCEV and vPMCnonlesion group. The second canonical variable clustered vPMCEV and vPMCnonlesion neurons but was not significant (p = 0.52, eigen value = 3.8).