Abstract

Recent executive orders have led some applied behavior analysis (ABA) providers to interpret themselves as “essential personnel” during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this article, we argue against a blanket interpretation that being labeled “essential personnel” means that all in-person ABA services for all clients should continue during the COVID-19 pandemic. We believe this argument holds even if ABA providers are not in a jurisdiction currently under an active shelter-at-home or related order. First, we provide a brief description of risks associated with continued in-person ABA service delivery, as well as risks associated with the temporary suspension of services or the transition to remote ABA service delivery. For many clients, continued in-person service delivery carries a significant risk of severe harm to the client, family and caregivers, staff, and a currently overburdened health care system. In these situations, ABA providers should temporarily suspend services or transition to telehealth or other forms of remote service delivery until information from federal, state, and local health care experts deems in-person contact safe. In rare cases, temporary suspension of services or a transition to remote service delivery may place the client or others at risk of significant harm. In these situations, in-person services should likely continue, and ongoing assessment and risk mitigation are essential.

Keywords: Autism, COVID-19, Decision making, Essential services, Ethics, pandemic

On March 23, 2020, the New England Journal of Medicine published a commentary titled “Fair Allocation of Scarce Medical Resources in the Time of Covid-19” (Emanuel et al., 2020). The article provided ethical guidelines for rationing health care for patients who are ill from the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Using current highly valued Western ethical principles and medical knowledge of COVID-19’s impact on health care systems, the authors described how hospitals may allocate medical supplies when there are not enough resources to treat every sick person. The result of these challenging decisions is that some people will live and, unfortunately, some will die.

The seriousness and severity of COVID-19 caused the State of California to issue an executive order on March 19, 2020, that required citizens to shelter in place, save for essential personnel who provide life-sustaining services. Within 8 days, 23 states had followed suit and ordered residents to either shelter at home or to remain at home for an extended duration, where possible (e.g., 3 weeks or more). Sheltering at home is likely to reduce the spread of COVID-19, which, in turn, will reduce the burden on medical personnel, slow consumption of limited medical supplies, and, most importantly, save lives (Desai & Patel, 2020; Emanuel et al., 2020). Though states enacting shelter-at-home orders are consistent in allowing essential personnel to continue working, the definition of essential personnel varies from state to state.

The circumstances we find ourselves in raise important and difficult questions for applied behavior analysis (ABA) providers who serve individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). For example, Michigan (State of Michigan, 2020) and Ohio (State of Ohio, 2020) were among many states where ABA services for individuals with ASD were interpreted as essential. A major challenge in this designation is that in-person ABA service delivery likely involves physical contact or proximity between two or more people. This close contact places ABA providers1 and ABA consumers,2 and the community within which both groups travel, at an increased risk of contracting COVID-19. This is a serious concern that should not be overlooked and raises an important question: Are ABA providers essential personnel?

In this article we argue against universal decisions to continue or to stop ABA service delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic. This recommendation holds even if ABA providers are not in a jurisdiction currently under an active shelter-at-home or related order. Instead, ABA providers’ decisions about continuing ABA services during the COVID-19 pandemic should be made on a client-by-client basis. To assist in this analysis, we offer one potential decision-making process that may help mitigate risk while ABA providers make the difficult decision of whether to continue providing in-person services to clients with ASD.

A Blanket Designation of ABA as Essential During a Pandemic Is Concerning

The blanket interpretation of ABA as an essential service is a major concern if it results in ABA providers continuing to provide in-person services for all clients they serve, or for all clients or ABA consumers who request that services continue. COVID-19 spreads rapidly and can live in the air for over 3 hr and on some surfaces for up to 3 days (van Doremalen et al., 2020). A recent analysis from China indicates that approximately 80% of people infected with COVID-19 are asymptomatic or have mild symptoms (Wu & McGoogan, 2020).3 ABA providers who continue to conduct in-person services are at an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 themselves because of their frequent contact with others, are likely to be unaware they have it, and will be unaware they are spreading the disease to others, including clients and their families. Ultimately, continuing to provide in-person ABA services increases the risk that more people will become ill than if in-person ABA services stop.

Participating in the spread of COVID-19 is ethically consequential for several reasons. As of writing this article on March 28, 2020, research from China estimates 14% of people who contract COVID-19 will require hospitalization and 2.3% of people who contract COVID-19 will die (Wu & McGoogan, 2020). This is ethically consequential for the health and life of ABA consumers and providers. Individuals with ASD are more likely to have allergies and autoimmune diseases than the general population (Chen et al., 2013), placing them at greater risk of requiring hospitalization because of COVID-19. Under ideal conditions, many hospitals are not prepared to support the communication and behavioral needs of individuals with ASD (Vaz, 2010). To compound the previous points, the states of Arizona and Washington have issued policies that people with disabilities have a lower priority to receive critical and lifesaving medical care (Silverman, 2020), although these policies are out of compliance with the Office of Civil Rights (2020) bulletin issued on March 28, 2020. Even so, confusion around this issue could further limit access to lifesaving care for people with disabilities, including individuals with ASD. Efforts to keep clients out of the hospital must, therefore, be a top priority for ABA providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. The BACB Professional and Ethical Compliance Code for Behavior Analysts (2014; hereafter referred to as the BACB Code) obligates Board Certified Behavior Analysts (BCBAs) to operate in the best interests of their clients (Section 2.0) and to put their clients’ care first (Section 2.04d).4 In some situations, maximizing the best interest of a client and placing his or her care first might mean stopping in-person ABA services to reduce the likelihood that ABA consumers or providers (especially behavior technicians) contract COVID-19.

Participating in the potential spread of COVID-19 is also ethically consequential for the health of the broader community. In many locations, the current pandemic is placing severe economic strain on already-burdened communities (e.g., Haslem, 2020). Additionally, participating in the potential spread of COVID-19 raises the probability of increasing the burden on a health care system presently under tremendous resource strain (Emanuel et al., 2020). There are currently not enough health care resources for everyone who contracts COVID-19. Because of the lack of health care resources, health care providers must make decisions that balance maximizing benefits and minimizing harms for each patient versus maximizing benefits and minimizing harms for an entire community. ABA providers have not had to enter this conversation historically. But this conversation is on our doorstep. Additionally, the probability of increasing health care risks to others in our community and the broader public health care system is a relevant variable in the decision-making process as to whether to continue providing in-person ABA services.

A Blanket Designation to Stop All In-Person ABA Services Is Concerning

Some clients may have behavioral difficulties that could result in extreme harm to themselves or others, such as family members. For the purpose of this article, extreme harm is defined as injury sufficient to warrant medical attention. Without existing data, it is unclear how many ABA consumers fall into this category, although it seems likely that ABA providers are capable of making reasonable assessments of this with their clients. However, we suspect it is a minority of consumers and that clients with these extremely severe behavioral topographies are an exception, not the norm. Nevertheless, in-person ABA services may be necessary to protect or sustain the life of a client in some situations, despite the risk of contracting COVID-19. It is additionally worth considering that school closures, stay-at-home orders, and overall massive changes to ABA consumers’ daily routines may dramatically intensify problem behavior.

Withdrawing ABA services for clients with ASD who require services to protect or sustain life is ethically consequential for several reasons. Some clients may have a history of, or currently display, challenging behavior that carries some probability of risk of harm to themselves and others. A decision to cease or significantly alter in-person treatment could lead to an increase in the severity or intensity of challenging behavior (e.g., Briggs, Fisher, Greer, & Kimball, 2018; Fuhrman, Fisher, & Greer, 2016; Kimball, Kelley, Podlesnik, Forton, & Hinkle, 2018; Lambert, Bloom, Samaha, & Dayton, 2017; Romano & St. Peter, 2016), which could result in the client or others, such as a family member, being hospitalized. The probability of harm from challenging behavior has to be balanced against the probability of contracting COVID-19 through continued in-person services. To compound this calculation, hospitalization also carries an increased probability of an unaffected patient contracting the virus while hospitalized because hospitals carry increased risk of hospital-acquired infection and disease (e.g., Chowdhury, Miller, Lewis, Niesley, & Patel, 2016; Gestal, 1987; Haverstick et al., 2017). Thus, blanket decisions to stop all ABA services may place some ABA consumers at risk of severe harm to themselves or others, as well as, ironically, at an increased risk of contracting COVID-19 if hospitalized.

Withdrawing ABA services for clients at high risk is also ethically consequential for the broader geographical and ABA communities. For the broader geographical community, almost half of children with ASD have been reported to engage in elopement (Anderson et al., 2012). In the current crisis, a child who runs away from home requires much-needed community resources (e.g., police and ambulances). Relatedly, if services are withheld and the client with ASD ends up hospitalized, extra hospital resources might be required to support any communication and behavioral needs the person may require while hospitalized (Vaz, 2010).

Thus, to summarize the ethical dilemma, many ABA providers have found themselves in a position where they need to decide whether to continue providing in-person ABA services or to withhold in-person ABA services. Each option carries significant risk of harm to ABA consumers, ABA providers, and the larger geographical, medical, and ABA communities. As with many ethical dilemmas, this is a living, breathing decision-making context. Unlike many ethical dilemmas, the facts, probabilities, and risks of harm from contracting COVID-19 are dynamically changing. ABA providers will need to regularly reevaluate their decisions to provide or withhold treatment according to dynamically changing client needs. It is our position that this decision is best made on a case-by-case basis.

Case-by-Case Decision Framework to Continue or Postpone ABA Services During a Pandemic

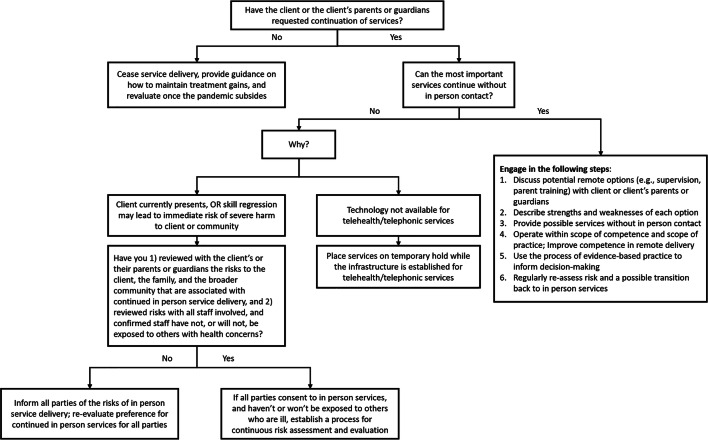

The ethical dilemma ABA providers currently find themselves in is incredibly complex and difficult. Figure 1 provides one potential framework for how ABA providers may decide whether to continue ABA services for each client. This framework is based on the authors’ collective belief that the decision to continue services should be made on a client-by-client basis involving ongoing, thorough, and careful risk assessments in conjunction with the BACB Code and relevant federal, state, and local policies and laws. We also highlight what we believe are currently the most important considerations within that decision-making framework. No single person has all the answers, and no one can generate an optimal solution that all can follow. We hope that readers will find the decision-making model useful and identify gaps in our logic so they can improve upon it for their unique situations.

Fig. 1.

A proposed process for risk mitigation during the COVID-19 pandemic

In brief, the logic of the decision-making framework is as follows. ABA providers in leadership roles should not force unnecessary risk on ABA consumers (e.g., clients and their families), behavior technicians or their families, or the larger geographical community. If the client or the client’s legal guardians have not requested for services to continue, then services should stop until the COVID-19 pandemic subsides. If services are requested to continue, then ABA providers must decide whether they can pivot to telehealth or other remote service delivery method (e.g., phone). If they can pivot to telehealth, issues of training, scope of competence, and using the decision-making process of evidence-based practice need to be addressed. If ABA providers cannot pivot to telehealth, then the barriers and issues surrounding the effective and safe delivery of ABA treatment need to be addressed (BACB, 2014). If barriers are technological, the risks of serious illness or death from COVID-19 seem to outweigh the risks of withholding in-person services, and ABA services should be temporarily suspended while the infrastructure for remote service delivery is put in place. If the barriers are behavioral (i.e., severe risk of harm or regression), then standard practices of informed consent that include the potential risks associated with in-person delivery should follow. Of particular emphasis, we believe the consent of all ABA providers involved in conducting in-person services, including behavior technicians, must also be obtained. Next, we discuss each major point in turn.

Pivot to Telehealth or Other Remote Service Delivery Method

Because spreading COVID-19 during in-person ABA service delivery is highly probable, we strongly recommend that most in-person services be temporarily paused until public health officials indicate a particular community, county, or state has the medical capacity to support those who are, or may become, seriously infected with COVID-19. This recommendation holds even if ABA providers are not in a jurisdiction currently under a shelter-at-home order. Fortunately, an alternative behavior exists that is reimbursable and executable using readily available resources. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has mandated that the telehealth delivery of ABA services can be reimbursed through health insurance companies (HHS, 2020). For those who lacked the infrastructure to provide telehealth services before the pandemic, the HHS has also stated that regulatory noncompliance law will be relaxed to allow health care providers to build out and learn to use telehealth modalities (HHS, 2020). Given the widely available and accessible nature of audio (e.g., phone) and video (e.g., FaceTime, Zoom) technology, most ABA providers should be able to manage some degree of contact with clients while adhering to social-distancing recommendations (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). It is worth noting that some insurance funders strictly require HIPAA-compliant platforms in their documents approving the use of telehealth services, so best practice would be to exhaust compliant options first. In the event a noncompliant platform is used, this should be clearly stated as a risk to confidentiality in informed-consent documents presented before the provision of telehealth services.

A rapid transition to telehealth or other remote service delivery method presents several issues for ABA providers with little experience in this area. Of primary concern is that individuals credentialed by the BACB are obligated to practice only within their scope of competence (BACB, 2014). Telehealth service delivery requires unique skills distinct from in-person service delivery (Pollard, Karimi, & Ficcaglia, 2017), and individuals credentialed by the BACB without training in this realm will likely need training and supervision before practicing telehealth or other remote service delivery method independently.

A current lack of competence in telehealth service delivery does not justify continued in-person service delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Individuals credentialed by the BACB are also ethically obligated to make genuine and ongoing efforts to obtain professional development and supervision to meet the present needs of their clients (see Brodhead, Quigley, & Wilczynski, 2018, and LeBlanc, Heinicke, & Baker, 2012, for recommendations on expanding one’s scope of competence). Fortunately, the Council for Autism Service Providers has a public repository with resources for delivering ABA services via telehealth and telephonic media (The Council of Autism Service Providers, 2020). We are also aware that the Journal of Behavioral Education will soon be publishing a special issue on telehealth. Additionally, informal observation suggests that several continuing education opportunities are available for BCBAs to obtain some background knowledge and training in telehealth delivery of ABA services.

In sum, where possible, a pivot to telehealth or other remote service delivery method seems to be the best solution to mitigate risk during the COVID-19 pandemic while continuing to provide some benefit of ABA to clients, even if the area in which ABA consumers reside is not presently under a shelter-at-home or related order. Remote service delivery requires a unique skill set that all individuals credentialed by the BACB might not have. Nevertheless, resources exist for professionals credentialed by the BACB to expand their scope of competence to execute a new treatment model (e.g., telehealth) while in-person services are temporarily withheld.

When Telehealth or Remote Service Delivery Is Not Possible

Remote service delivery may not be possible in some situations. One situation might be when the technological infrastructure required for remote service delivery is not in place for the ABA provider or consumer. Regardless, the potential risks of serious illness and death are likely greater than the risks of the temporary withdrawal of services if a lack of technological infrastructure is the only reason telehealth services cannot be delivered. In these situations, all reasonable attempts to build out the necessary infrastructure for remote service delivery should be made so that ABA services can resume as quickly as possible. Over 90% of Americans use the Internet (Anderson, Perrin, Jiang, & Kumar, 2019), and approximately 96% of Americans have a cell phone of some kind (Pew Research Center, 2019). Barriers that result from the lack of infrastructure can likely be addressed for most ABA consumers given the pervasive access to the Internet and cellular devices, along with the aforementioned changes that allow for telehealth and telephonic ABA services to be reimbursable.

As mentioned earlier, a second situation where telehealth or other remote service delivery method may not be possible might occur because removing in-person services would result in significant challenging behavior, or regression to significant challenging behavior. Here, ABA providers’ legal and ethical obligation to obtain informed consent indicates that all ABA providers (ranging from directors to behavior technicians) and all ABA consumers (ranging from the client to any people that client has frequent contact with) should agree to continue in-person services in light of the current information available. Although it is unclear exactly how much an intervention context needs to change before additional consent conversations are required, it is important to note that informed consent is regarded as an ongoing process and not a one-time decision (e.g., Bailey & Burch, 2016; Brody, 1989; Egan, 2008; Usher & Arthur, 1998).

Ongoing Risk Assessment Is Essential

The facts surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic, the probability and severity of clients’ challenging behavior and regression, ABA providers’ health status, and technological infrastructures are likely to change regularly. Ongoing risk assessment is important for all cases regardless of whether an ABA provider and ABA consumers agree that in-person ABA services should continue, stop, or transition to telehealth or other remote service delivery method. Within this conversation, it is important to note that some ABA providers may have preexisting conditions themselves that place them in a high-risk subgroup if they contract COVID-19. It is illegal for an employer to ask about the health status of an employee. To protect all ABA providers during the pandemic, agency leaders must respect any request for reassignment without penalizing the person who makes the request. Requiring behavior technicians, for example, to continue providing in-person services under threat of losing their jobs would be unethical and, in the long run, bad business for agency directors and owners. Rather, to avoid unduly influencing the ABA provider, the consent process should explicitly state the employee is not at risk of corrective action or loss of employment by avoiding in-person work during this time.

Ongoing risk assessment should encompass all individuals who live with or have regular contact with a client. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the health of people living in a client’s home likely remained largely unimpacted by ABA services and a behavior technician’s presence in that home. However, the biological processes of infectious disease impact health differently than the behavioral processes of ABA. Continued in-person service delivery includes the possibility that an ABA provider negatively impacts the health of other people living in a client’s home, as well as the health of the behavior technician’s family, even if this in-person contact occurs in a school or clinic. The risk associated with all ABA consumers must be accounted for on an ongoing basis.

ABA providers in leadership roles within their organizations should recognize that the client, the client’s family, and the behavior technician may not be fully aware of the risks associated with in-person ABA services during this pandemic. The ABA provider has an obligation to promote the short- and long-term benefits to the clients and the larger society (BACB, 2014). This creates a responsibility to inform ABA consumers and ABA providers of all ongoing risks in a manner that is easily understood. Information, and misinformation, about COVID-19 changes daily. Though behavior analysts are not experts in infectious diseases, it is our responsibility to inform clients of the objective risks they face (BACB, 2014).

Conclusion

Never, in our wildest dreams, did we imagine discussing ethical considerations for delivering ABA services during a pandemic. We are all in uncharted territory, and no one, including us, has all the answers. We recognize the approach to decision making we take in this article may negatively affect positive trajectories of individuals with ASD and potentially cause financial hardship for ABA providers, many of whom are our beloved friends and colleagues. However, we strongly believe that life is worth more than short-term economic hardships. Our friends, colleagues, clients, families, and members of the communities we serve all deserve to live long, healthy, and prosperous lives. We sincerely hope the considerations and decision-making framework provided in this article help ABA providers and consumers, as well as policy makers, with the numerous difficult decisions they face.

Authors Contribution

All three authors contributed equally to this manuscript and share first-author status.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

All three authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

We use the term ABA providers to refer to a range of professionals involved in ABA service delivery, ranging from clinical directors to frontline employees. When appropriate, we refer to specific ABA providers, such as behavior technicians, to highlight that specific provider’s role in the proposed analysis.

We use the term ABA consumers to refer to a range of individuals impacted by the services received from ABA providers. The term ABA consumers refers broadly to the client, the client’s caregivers or legal guardians, the client’s extended family, or other people who reside in the client’s home or are otherwise impacted by ABA services. When appropriate, we refer to specific ABA consumers, such as the client, to highlight that specific consumer’s role in the proposed analysis.

For up-to-date statistics on this dynamically changing situation, we encourage the reader to visit https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus

The BACB has published a document titled “Ethics Guidance for ABA Providers During COVID-19 Pandemic.” We direct the reader to https://www.bacb.com/bacb-covid-19-updates/

to review these guidelines and any updates issued by the BACB during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

David J. Cox, Email: dcox33@jhmi.edu

Joshua B. Plavnick, Email: plavnick@msu.edu

Matthew T. Brodhead, Email: mtb@msu.edu

References

- Anderson C, Law JK, Daniels A, Rice C, Mandell DS, Hagopian L, Law PA. Occurrence and family impact of elopement in children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2012;130:870–877. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M., Perrin, A., Jiang, J., & Kumar, M. (2019). 10% of Americans don’t use the Internet. Who are they? Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/22/some-americans-dont-use-the-internet-who-are-they/

- Bailey JS, Burch MR. Ethics for behavior analysts. 3. New York, NY: Routledge; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board . Professional and ethical compliance code for behavior analysts. Littleton, CO: Author; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs AM, Fisher WW, Greer BD, Kimball RT. Prevalence of resurgence of destructive behavior when thinning reinforcement schedules during functional communication training. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2018;51:620–633. doi: 10.1002/jaba.472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodhead MT, Quigley SP, Wilczynski SM. A call for discussion about scope of competence in behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2018;11:424–435. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-00303-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody H. Transparency: Informed consent in primary care. September/October: Hastings Center Report; 1989. pp. 5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). How to protect yourself. Retrieved on March 28, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fprepare%2Fprevention.html

- Chen MH, Su TP, Chen YS, Hsu JW, Huang KL, Chang WH, et al. Comorbidity of allergic and autoimmune diseases in patients with autism spectrum disorder: A nationwide population-based study. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2013;7:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2012.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury M, Miller D, Lewis M, Niesley M, Patel T. Impact of antimicrobial stewardship in collaboration with infection control on hospital-acquired infection rates in a subspecialty cancer treatment facility. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2016;45(Suppl. 1):275–276. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2016.02.610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Desai, A. N., & Patel, P. (2020). Stopping the spread of COVID-19. Journal of the American Medical Association. Advance online publication. 10.1001/jama.2020.4269

- Egan EA. Informed consent: When and why. AMA Journal of Ethics. 2008;10:492–495. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2008.10.8.ccas2-0808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel, E. J., Persad, G., Upshur, R., Thom, B., Parker, M., Glickman, A., … Phillips, J. P. (2020). Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of Covid-19. The New England Journal of Medicine. Advance online publication. 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fuhrman AM, Fisher WW, Greer BD. A preliminary investigation on improving functional communication training by mitigating resurgence of destructive behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2016;49:884–899. doi: 10.1002/jaba.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gestal JJ. Occupational hazards in hospitals: Risk of infection. British Journal of Industrial Medicine. 1987;44:435–442. doi: 10.1136/oem.44.7.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslem, U. (2020). The real Miami. The Players’ Tribune. Retrieved from https://www.theplayerstribune.com/en-us/articles/udonis-haslem-nba-covid-the-real-miami?

- Haverstick S, Goodrich C, Freeman R, James S, Kullar R, Ahrens M. Patients’ hand washing and reducing hospital-acquired infection. Critical Care Nursing. 2017;37:e1–e8. doi: 10.4037/ccn2017694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimball RT, Kelley ME, Podlesnik CA, Forton A, Hinkle B. Resurgence with and without an alternative response. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2018;51:854–865. doi: 10.1002/jaba.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JM, Bloom SE, Samaha AL, Dayton E. Serial functional communication training: Extending serial DRA to mands and problem behavior. Behavioral Interventions. 2017;32:311–325. doi: 10.1002/bin.1493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc LA, Heinicke MR, Baker JC. Expanding the consumer base for behavior-analytic services: Meeting the needs of consumers in the 21st century. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2012;5:4–14. doi: 10.1007/BF03391813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Civil Rights. (2020). Bulletin: Civil rights, HIPAA, and the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ocr-bulletin-3-28-20.pdf

- Pew Research Center. (2019). Mobile fact sheet. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/

- Pollard JS, Karimi KA, Ficcaglia MB. Ethical considerations in the design and implementation of a telehealth service delivery model. Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice. 2017;17:298–311. doi: 10.1037/bar0000053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romano LM, St. Peter CC. Omission training results in more resurgence than alternative reinforcement. The Psychological Record. 2016;67:315–324. doi: 10.1007/s40732-016-0214-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, A. (2020). People with intellectual disabilities may be denied lifesaving care under these plans as coronavirus spreads. ProPublica. Retrieved from https://www.propublica.org/article/people-with-intellectual-disabilities-may-be-denied-lifesaving-care-under-these-plans-as-coronavirus-spreads

- State of Michigan. (2020). Executive order 2020-21. Retrieved from https://www.michigan.gov/whitmer/0,9309,7-387-90499_90705-522626%2D%2D,00.html

- State of Ohio. (2020). Directors stay at home order. Retrieved from https://content.govdelivery.com/attachments/OHOOD/2020/03/22/file_attachments/1407840/Stay%20Home%20Order.pdf

- The Council of Autism Service Providers. (2020). Coronavirus—telehealth resources. Retrieved from https://casproviders.org/coronavirus-resources/telehealth/

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Notification of enforcement discretion for telehealth remote communications during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. Retrieved on March 27, 2020, from https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/emergency-preparedness/notification-enforcement-discretion-telehealth/index.html

- Usher KJ, Arthur D. Process consent: A model for enhancing informed consent in mental health nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1998;27:692–697. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Doremalen, N., Bushmaker, T., Morris, D. H., Holbrook, M. G., Gamble, A., Williamson, B. N., … Munster, V. J. (2020). Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. The New England Journal of Medicine. Advance online publication. 10.1056/NEJMc2004973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Vaz I. Improving the management of children with learning disability and autism spectrum disorder when they attend hospital. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2010;36:753–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z., & McGoogan, J. M. (2020). Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72,314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Journal of the American Medical Association. Advance online publication. 10.1001/jama.2020.2648 [DOI] [PubMed]