Introduction

Many aspects of recent healthcare reform in the United States have impacted technology, innovation, and delivery of care. The medical device industry is a substantial component of the healthcare system. As of 2019, the industry consists of 859 businesses in the U.S. with revenues totaling to $41.3 billion1. Though these statistics suggest a thriving, diverse playing field, the bulk of the market is actually comprised of a few large companies (Tables 1 and 2). These companies occupy 1% of the industry yet account for 82% of total assets.2,3

Table 1.

Top 10 U.S. medical device companies by revenue (2017)

| Company | Revenue in billion U.S. dollars | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Medtronic | 29.7 |

| 2 | Johnson & Johnson | 26.6 |

| 3 | General Electric Healthcare | 19.1 |

| 4 | Abbott Laboratories | 16.2 |

| 5 | Cardinal Health | 13.5 |

| 6 | Stryker | 12.4 |

| 7 | Becton Dickinson & Co. | 12.1 |

| 8 | Baxter International | 10.6 |

| 9 | Boston Scientific | 9 |

| 10 | Danaher | 8.6 |

Data from Statista. Medical Product Outsourcing. Top 10 U.S. Medical Technology Companies Based on Revenue in 2017 (in Billion U.S. Dollars). July 2018.

Table 2.

Top 5 global orthopedic device companies by market share (2017)

| Company | Market Share | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Johnson & Johnson (U.S.) | 24.2% |

| 2 | Zimmer Biomet (U.S.) | 20.3% |

| 3 | Stryker (U.S.) | 16.3% |

| 4 | Medtronic (U.S.) | 8.3% |

| 5 | Arthrex (Germany) | 5.8% |

Data from Statista. Global Top 10 Companies Based on Orthopedic Medical Technology Market Share in 2017 and 2024. September 2018.

In contrast, small companies, with 73% having fewer than 20 employees and less than $1 million in assets, are often acquired by large companies due to challenges with securing funding, manufacturing, distribution, and a lack of established relationships with providers. Yet these companies are crucial to the development of new medical technologies, and often focus on narrow therapeutic areas2,4. Healthcare policies that create further market barriers for small companies pose the risk of stunting medical innovation.

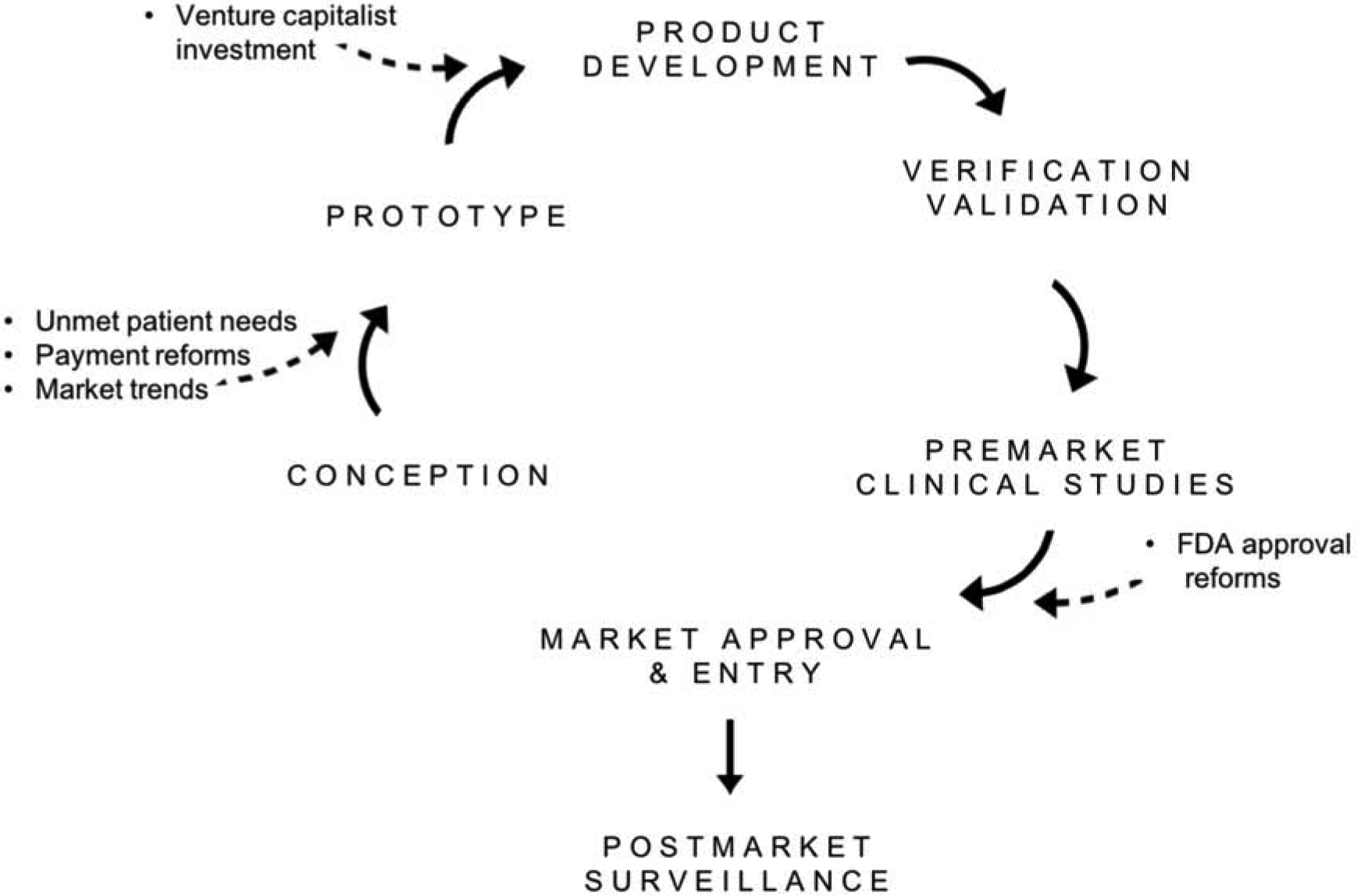

Prior to use in patient-care settings, medical devices undergo a multi-step product development process (Figure 1). This process begins with product conception and prototyping. In small and start-up companies, this stage requires adequate funding, which is typically assumed by venture capitalist firms and government grants2. The product then undergoes verification and validation analyses to ensure that it meets design and market criteria. Once the product has been deemed ready for market entrance, it must undergo an FDA regulated premarket approval process after which it can enter the market and undergo long-term postmarket surveillance7.

Figure 1.

Medical Device Development Process and Factors Influencing Device Innovation.

Healthcare reforms centered around improved patient outcomes and cost reduction have had a significant impact on the medical device market and device innovation. Changes in venture capitalist investment, allocation of R&D funds, and the FDA approval process are among many changes in the industry. The following sections will explore the driving forces of these changes and the resulting challenges faced by various stakeholders.

Venture capitalist investment trends

In the last decade, payment reforms and uncertainties in reimbursements have led to decreased venture capitalist investment in medical device companies. Between 2009–2014, total venture capital invested in all industry sectors increased dramatically from $20.3 billion to $39.6 billion. Investment in life science companies, however, decreased from 35.7% to 19.9% of total investment. Overall, medical technology share of total VC investment decreased from 9% in 2009 to 4% in 20148. A larger decline in investment in early-stage life science companies compared to later-stage life science companies was also observed during this time9.

In a survey of more than 150 VCs, 40% of respondents stated uncertainties over coverage and reimbursement policies of new products by CMS and private payers as one of the main reasons for hesitation to invest in life science companies9. The new model of value-based purchasing favors more clinical evidence, incurring higher costs that discourage VC investment. In addition, VCs find FDA medical device product review to be slow and inconsistent. The total time required to gain FDA approval and insurance coding, coverage, and payment creates delays in return on investment that are unattractive to VCs.

Industry stakeholders have found investment trends to be concerning for future innovation and have called upon multiple policy changes to encourage VC investment. One such policy is increased transparency and timely pathways to coding, coverage, and payment for FDA approved products. Increased government agency funding for start-up company R&D has also been suggested9.

Implications of payment reform

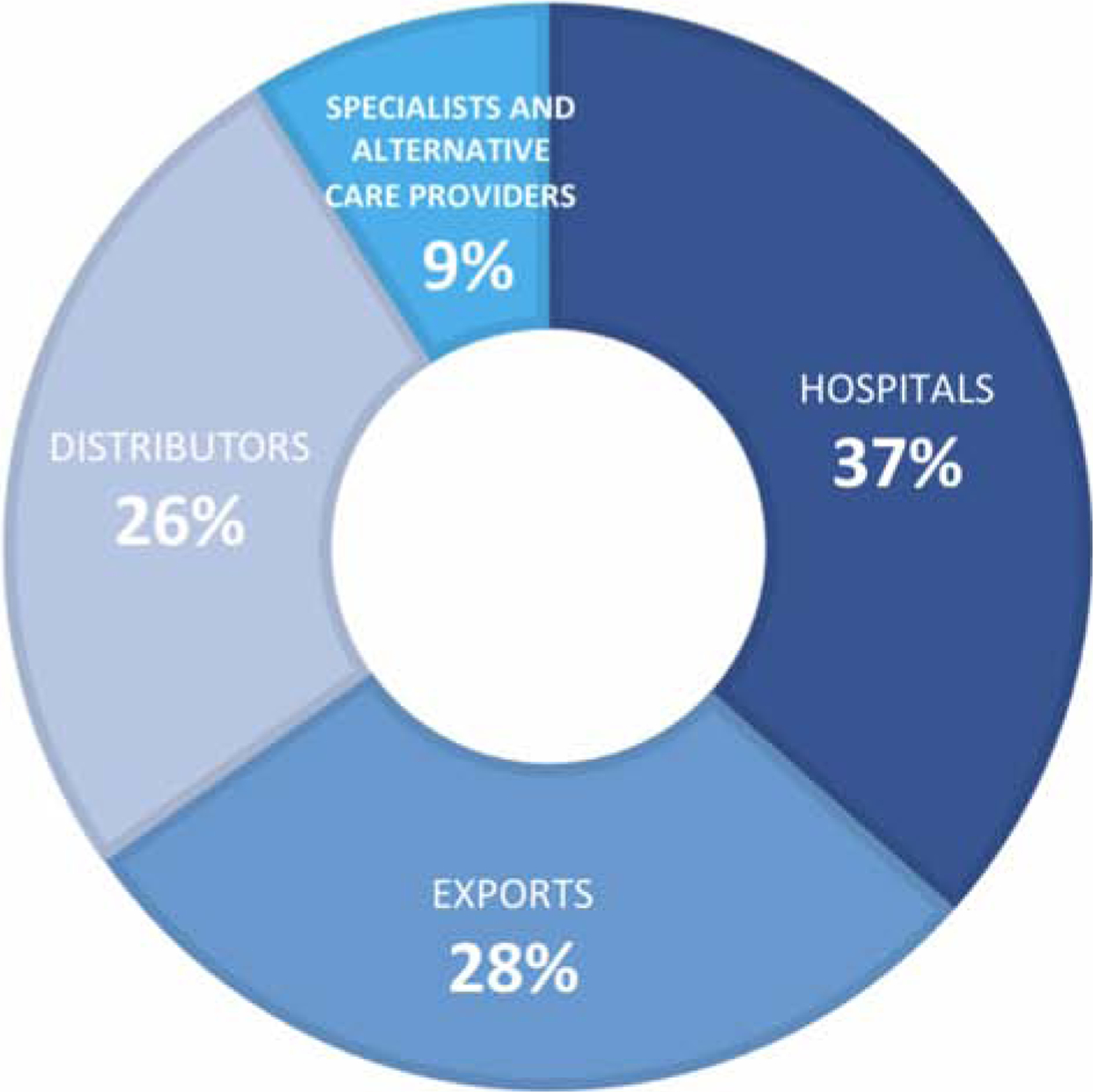

The introduction of new payment models that prioritize positive patient outcomes and cost reduction has incentivized providers to seek out low-cost medical devices. This has in turn altered the market for various purchasing powers. For example, in bundled payments, a fixed rate is set in advance for a surgical procedure. This fixed rate includes implantable devices, supplies, drugs, etc10. In order to improve profit margins, hospitals must negotiate for lower device prices. With hospitals being the largest market for medical device manufacturers (Figure 2), this theoretically would exert a downward pressure on prices that is passed down to suppliers11.

Figure 2.

Market Segmentation of the U.S. Medical Device Industry (2019). Adapted from Curran J. IBISWorld Industry Report 33451b Medical Device Manufacturing in the US. June 2019; with permission.

Challenges in Cost Reduction

Although reforms in payment models have pushed hospitals to lower costs, medical device cost is dependent on multiple factors. The ideal forces necessary to control cost in any market are:

large number of sellers

existence of similar products in the market

low barriers to entry into the market, and

transparency in prices, quality, and performance of products2,10.

The market for low-risk devices such as examination gloves possess many of these forces, resulting in a highly competitive market. In contrast, the market for high-risk devices lacks these forces, allowing them to charge higher prices for their products and sustain considerable profits.

There are relatively few manufacturers that supply the majority of high-risk devices. For example, 5 manufacturers control 90% of the market for hip and knee implants10. Furthermore, lack of price transparency limits hospitals from negotiating prices with suppliers. Device manufacturers often require a confidentiality agreement in the purchasing contract with hospitals, which prevents hospitals from disclosing prices to physicians, patients, and insurers12. As a result, it becomes difficult to determine price differences among hospitals, a significant setback for price negotiations. It should be noted that there is increasing public demand for price transparency13, which may ultimately shift the landscape for negotiation and price setting.

Innovation Trends

Current emphasis on cost-reduction while maintaining quality patient care has led to new trends in technological innovation. Frugal innovation, which involves creating simpler products with lower unit cost, has become increasingly sought after by the medical device industry. A subset of frugal innovation, “reverse innovation”, specifically has potential in reducing healthcare expenditure. The phrase refers to developing simpler versions of medical equipment that is already in the market, with the assumption being that these simpler versions will greatly reduce the cost of production and operation14. For example, Siemens developed a fetal heart rate monitor that relies on simple microphones as opposed to expensive ultrasound technology that requires specialized training. Not only does this reverse innovation reduce production costs, but also, eliminates the added cost of specialized personnel to operate the device. Often, these “reverse innovations” are born out of resource-poor nations14. A prime example is the Stanford-JaipurKnee, a $20 high-performance prosthetic knee joint for amputees who are unable to afford more expensive alternatives that currently populate the market.

Deinstitutionalization, or the creation of innovations that reduce high-cost inpatient care, has also emerged in recent years. These innovations are largely centered around remote monitoring of patients14. One such innovation, electronic consultations (eConsults), which reduces the need for in-person specialty consultation, proved that high-quality care can be provided to patients at lower cost. Specialties studied include orthopedics, dermatology, endocrinology, and gastroenterology. On average eConsults was $84 lower per patient per month, with annual savings of over $578,592 for Medicaid15. When used in the right patient population and circumstances, such innovations could become a part of mainstream medical practices, and aid in the mission of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to provide high-quality care at lower cost.

Implications of comparative effectiveness research

In 2010, the ACA created a new independent entity, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) that was tasked with funding and disseminating comparative effectiveness research (CER). CER has been used for many decades prior to the ACA, though it gained popularity in light of value-driven healthcare reforms. Currently, CER functions to identify and eliminate care that is no more effective than cheaper alternatives.

While CER offers many benefits to payers, it also has certain disadvantages. Policies guided by CER will likely lead to better coverage of comparatively effective treatments. However, there will always be a subset of patients that do not respond well to treatments judged favorably by CER. Additionally, there will be treatments that do not lend themselves to be rigorously evaluated by CER, such as a lower extremity limb reconstruction and brachial plexus reconstruction, given the vast heterogeneity of clinical presentations. With coverage policies guided by CER, it will be more difficult for these subsets of patients to have access to alternative treatments. Similarly, coverage policies guided by CER could stifle treatment innovations that are only effective in a minor population of patients16.

Implementation of CER poses unique challenges. Because CER will be used to guide future policies and influence the types of devices present in the market, it is critical that these studies are adequately designed and interpreted. Potential challenges include the short life cycle of medical devices and relatively short time frame of these studies.

Medical devices have short life cycles due to incremental changes that are made to devices after entering the market. These incremental changes are common. For example, the median number of postmarket changes in an orthopedic device’s life span is 6.5. 22% of these changes have altered the device design or components17. At this rate, devices become substantially different over the years from that which was initially approved, a process known as “design drift”17.

The rapid rate of change in these devices would make it difficult for CER studies to adjust their study design, resulting in findings that would be based on medical technology that is several generations older than current devices available in the market. Because many of these adjustments can cause significant changes in device safety and efficacy, CER and the policies guided by these studies would not accurately reflect these changes18.

In addition, medical devices often require up-front costs, though cost-effectiveness improves over a lifetime. CER studies involving medical devices, however, evaluate patient outcomes over relatively shorter periods of time, therefore full clinical benefit may not be observed during this timeframe. This must be taken into consideration when evaluating medical devices against other therapies. For example, the cost effectiveness of implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapies can range from about $150,000 to US $300,000 at 3 years, but drops substantially to about $50,000–100,000 over a lifetime19.

CER provides a systematic approach to evaluating the efficacy of medical devices. In the future, policies driven by CER must consider the beneficial and harmful effects that CER may have on market diversity. Furthermore, limitations of CER due to short device life cycles and methodologic shortcomings must also be considered.

Reforms in device approval and surveillance

The FDA categorizes medical devices into three classes, Class I, II, or III, based on the risk they pose to patients (Table 3). Devices that pose greater risk are subject to more regulatory controls and are required to provide evidence of safety and efficacy. Class I, or low-risk devices such as gloves and routine surgical equipment, generally do not require FDA review before they are marketed. On the other hand, Class II devices require 510 (k) notification in which the device must demonstrate that it is “substantially equivalent” to another device in the market20. Lastly, Class III devices, such as heart valves and orthopedic implants, must submit a premarket approval application, which requires clinical data demonstrating safety and efficacy of the device2.

Table 3.

FDA classification of medical devices

| Category | Examples | Approval requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Class I (Low risk) |

|

Registration only |

| Class II (Moderate risk) |

|

510(k) notification |

| Class III (High risk) |

|

Premarket approval application |

Adapted from The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). An overview of the medical device industry. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System. Washington, D.C.: 2017; with permission.

Premarket Approval

The premarket approval process has in recent years drawn criticism for allowing high-risk devices to pass into the market without robust clinical data. It has also been criticized for approving changes to high-risk devices already existing in the market. This process consists of filing “supplements”, which tend to have short review times and requires minimal supporting data. The number of supplements that can be submitted per device is unlimited. Hence, a device can undergo a series of changes resulting in a version that is substantially different from the initial premarket approval. Such was the case for a femoral component of a hip replacement device that was found to fracture prematurely on the left side when the location of the etched icon of the company was changed to the left side18. The ability of manufacturers to make design changes to high-risk devices without adequate oversight and supporting clinical data poses a significant safety concern to patients.

The 510(k) notification process has been the main focus of recent premarket approval reform efforts. The 510(k) requires devices to be “substantially equivalent” to those in the market, and was enacted as a part of the 1976 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act21. The process requires manufacturers to prove equivalence to a device that is already on the market, known as a predicate device, of their own choosing. Many of these predicate devices were cleared through the 510(k) with pre-amendment devices serving as predicate devices. In effect, devices are being compared to pre-amendment safety standards, when there were no requirements for manufacturers to provide clinical evidence. Furthermore, the criteria used to approve a device as “substantially equivalent” is unclear and inconsistent. The process also lacks transparency, preventing physicians and patients from educating themselves on the devices they are using22. Therefore, “substantially equivalent” does not necessarily indicate that a product is safe or efficacious.

The DePuy ASR XL Acetabular System for total hip arthroplasty provides an example of the flaws of the 510(k) notification. In 2005, the ASR was cleared by the FDA under the grounds of being “substantially equivalent” to existing implants. Following market entry, it was found that 21% of these implants had to be revised within 4 years23. In reviewing the case, it was brought to light that the ASR, though a Class III device, was able to be approved through the 510(k) as opposed to the lengthier premarket approval process23. Furthermore, the predicate device used for 510(k) approval was significantly different in design from the ASR. The ASR is a “metal-on-metal” type of articulation between components of the hip replacement, whereas the predicate devices are largely “metal-on-plastic”24.

Although some are urging the FDA to require more clinical data prior to market entrance, the medical device industry has concerns over increased regulation on time to market and its potential to stunt innovation. The FDA has since been tasked with balancing the concern for premature market entrance with potential delay in time to market. Recently, the FDA has taken steps to strengthen 510(k). Among these efforts are (1) eliminating the use of 510 (k) for class III devices. Between 2003 and 2009, there were on average, 80 submissions for Class III devices cleared through 510(k). In 2018, this was brought down to zero25. (2) Use of newer predicates. Previously, 20% of 510(k) were cleared based on predicates that were greater than 10 years old. In order to more closely reflect modern technology, the FDA plans on developing proposals to “sunset” older predicates. (3) Establishment of an alternative 510(k) pathway, the “Safety and Performance Pathway”. The pathway would provide manufacturers with objective safety and performance criteria recognized by the FDA as substantial equivalence. This would in turn create transparency for payers who are looking to compare similar devices in the market25.

Postmarket surveillance

As a part of premarket approval, medical devices often undergo studies that are small-scale and in limited patient populations. Following approval, these products are utilized in a highly diverse patient population, and over extended periods of time. Accordingly, it is critical that these devices continue to be monitored for safety and efficacy in these new settings through postmarket surveillance.

Postmarket surveillance methods can be broadly classified as passive and active26. Medical Device Reporting (MDR) remains at the core of the FDA’s passive surveillance methods. Medical device related adverse events can be reported to MDR by manufacturers, physicians, and patients. The FDA, however, has been criticized for delayed and inconsistent response to these reports. Furthermore, many of the reports were missing critical information regarding the adverse event and device identification. This has in turn made it difficult to tease out device malfunction from procedural and user errors22,26. The combination of inadequate reporting to FDA and inconsistent FDA response has led to a broken and outdated system for monitoring the increasingly complex and high-risk medical devices being approved today.

Active surveillance consists of clinical studies and medical product registries that collect safety and performance data. The FDA can mandate studies under 2 provisions, postapproval and 522 studies. Postapproval studies can be ordered alongside a premarket approval application, whereas 522 studies can be mandated at any time during a device’s life cycle. The postapproval registry surveillance is another form of active surveillance, and can provide long-term safety information unable to be provided by short-term trials26.

In recent years, medical device recalls have led to concerns regarding the FDA’s postmarket surveillance methods. Aware of these shortcomings, the FDA responded to these concerns with a series of reforms beginning in 201220. Together these reforms aimed to create a systematic method of collecting and analyzing medical device performance data. The first of these reforms was establishing the unique device identification (UDI) system. UDI provides standardization in documenting devices. As a result, the investigation of adverse event reports can be conducted in a timely manner. It also aids in effectively organizing recalls27.

The second main reform was the development of the National Evaluation System for health Technology (NEST). NEST received seed funding in 2016 and has since been run by the non-profit Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC)28. Through NEST, the FDA will gain access to multiple sources of electronic health data including insurance claims and medical device performance. With systematic long-term data collection, NEST can facilitate device evaluation across a large patient population, and also help identify potential safety concerns sooner20.

Medical device excise tax

In 2013, the ACA imposed a 2.3% excise tax on medical devices, one of many provisions that served as a revenue source for healthcare reform. It was projected to collect $29 billion of net revenues over 10 years. Since the introduction of this tax, there has been a large debate surrounding the potential harm it may pose to research and development in medical device companies. In light of this controversy, a 2 year moratorium was imposed on the tax29.

Opponents of the medical device tax claim that it will reduce R&D spending by approximately 20%. In recent years, R&D investment has been declining (15.5% in 2000–2007 to 4.7% in 2013–201730). Though this is likely multifactorial, opponents are concerned that implementing the tax would lead to an even higher reduction in R&D expenses. The tax would also have a negative impact on small and start-up companies since it is based on a fixed percentage of sales, and these companies do not typically achieve profitability until their annual sales exceeds $100-$150 million. Because small companies are a major source of innovation, this could likely stunt development of new technologies11,29.

Proponents of the tax claim that it serves as a revenue source for financial health reform, and it would be difficult to find alternative sources. Furthermore, the tax will offset increased profitability for medical devices as a result of healthcare expansion3.

In early 2019, a bipartisan bill known as the Protect Medical Innovation Act of 2019, was introduced in both the House of Representatives and Senate. This bill would permanently repeal the medical device excise tax effective 2020.

Conclusions

The medical device industry has withstood many changes as a result of value-based healthcare reforms. These reforms have impacted device development at various stages, mainly funding for prototyping and the market approval process. Increased regulations surrounding premarket approval and postmarket surveillance have improved the safety of devices entering the market, though will likely increase time to market, an unfavorable effect for entrepreneurs and manufacturers alike. In addition, the introduction of new payment models has driven the creation of cost-efficient innovations. However, market dynamics continue to be difficult to change due to lack of price transparency and control of the market by a small number of sellers. Lastly, comparative effectiveness research serves as a useful tool for creating value-based coverage policies. In order to promote healthcare equity, policy makers must take into consideration the impact CER has on accessibility of alternative treatments for patient subgroups.

Key Points.

Recent healthcare reforms prioritizing cost reduction and improved patient outcomes have altered medical device innovation and market regulations.

Value-based payment reforms have cultivated new trends in innovation such as frugal innovation and deinstitutionalization; however uncertain reimbursement policies have led to a reduction in venture capitalist investment in new technologies.

Concerns over medical device safety due to a lenient market approval process has led to increased U.S. Food and Drug Administration regulations, yet this must be balanced with the resulting increased time to market, as this may stifle innovation.

Comparative effectiveness research has recently gained momentum, though application of its findings proves difficult due to the short life cycle of medical devices.

Synopsis.

The medical device industry has long been subject to criticism due to lack of price transparency and minimal regulations surrounding device approval. Often these have functioned as barriers to providing quality and cost-effective care to patients. Recent healthcare reforms aimed at overcoming these barriers have drastically changed medical device industry practices. Among these reforms are improving market approval regulations, increasing postmarket surveillance, and utilizing comparative effectiveness research. Moreover, these reforms have prompted increasingly cost-aware healthcare practices, which have encouraged new trends in medical device innovation such as frugal innovation and deinstitutionalization. This chapter will explore the challenges faced by industry, physicians, and patients in light of these reforms.

Disclosure statement

NIH NIAMS grant K23AR073928.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Preethi Kesavan, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri.

Christopher Dy, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri.

References

- 1.Curran J IBISWorld Industry Report 33451b Medical Device Manufacturing in the US. June 2019.

- 2.Report to the Congress: Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System. An overview of the medical device industry. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gravelle: The medical device excise tax: Economic analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donahue G, King G. Estimates of medical device spending in the United States.

- 5.Statista. Medical Product Outsourcing. Top 10 U.S. Medical Technology Companies Based on Revenue in 2017 (in Billion U.S. Dollars). July 2018.

- 6.Statista. Global Top 10 Companies Based on Orthopedic Medical Technology Market Share in 2017 and 2024. September 2018.

- 7.Panescu D Medical device development In: 2009. Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Minneapolis, MN: IEEE; 2009:5591–5594. doi: 10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5333490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Innovation Counselors LLC. A future at risk: Economic performance, entrepreneurship, and venture capital in the U.S. medical technology sector. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleming JJ. The Decline Of Venture Capital Investment In Early-Stage Life Sciences Poses A Challenge To Continued Innovation. Health Affairs. 2015;34(2):271–276. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lind K Understanding the market for implantable medical devices.

- 11.Nexon D, Ubl SJ. Implications Of Health Reform For The Medical Technology Industry. Health Affairs. 2010;29(7):1325–1329. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson J, Bridy A. Confidentiality and transparency for medical device prices: Market dynamics and policy alternatives.

- 13.Wilensky G Federal Government Increases Focus on Price Transparency. JAMA. 2019;322(10):916. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.12912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattke S, Liu H, Orr P. Medical Device Innovation in the Era of the Affordable Care Act: The End of Sexy. Rand Health Q. 2016;6(1):9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson D, Villagra VG, Coman E, et al. Reduced Cost Of Specialty Care Using Electronic Consultations For Medicaid Patients. Health Affairs. 2018;37(12):2031–2036. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basu A, Jena AB, Philipson TJ. The impact of comparative effectiveness research on health and health care spending. Journal of Health Economics. 2011;30(4):695–706. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samuel AM, Rathi VK, Grauer JN, Ross JS. How do Orthopaedic Devices Change After Their Initial FDA Premarket Approval? Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®. 2016;474(4):1053–1068. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4634-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jalbert JJ, Ritchey ME, Mi X, et al. Methodological Considerations in Observational Comparative Effectiveness Research for Implantable Medical Devices: An Epidemiologic Perspective. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2014;180(9):949–958. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma A, Blank A, Patel P, Stein K. Health care policy and regulatory implications on medical device innovations: a cardiac rhythm medical device industry perspective. Journal of Interventional Cardiac Electrophysiology. 2013;36(2):107–117. doi: 10.1007/s10840-013-9781-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medical Device Safety Action Plan: Protecting Patients, Promoting Public Health. 2018.

- 21.Wizemann T Public Health Effectiveness of the FDA 510(k) Clearance Process: Balancing Patient Safety and Innovation: Workshop Report. 2010. [PubMed]

- 22.Fargen KM, Frei D, Fiorella D, et al. The FDA approval process for medical devices: an inherently flawed system or a valuable pathway for innovation? Journal of NeuroInterventional Surgery. 2013;5(4):269–275. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2012-010400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curfman GD, Redberg RF. Medical Devices — Balancing Regulation and Innovation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(11):975–977. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen D Out of joint: The story of the ASR. BMJ. 2011;342(May13 2):d2905–d2905. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d2905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.FDA Has Taken Steps to Strengthen The 510(k) Program. November 2018.

- 26.Rajan PV, Kramer DB, Kesselheim AS. Medical device postapproval safety monitoring: where does the United States stand? Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8(1):124–131. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.001460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daniel G, Colvin H, Khaterzai S, McClellan M, Aurora P. Strengthening Patient Care: Building an Effective National Medical Device Surveillance System. February 2015.

- 28.National Evaluation System for Health Technology (NEST). June 2019.

- 29.Lee D Impact of the excise tax on firm R&D and performance in the medical device industry: Evidence from the Affordable Care Act. Research Policy. 2018;47(5):854–871. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2018.02.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pulse of the Industry: EY Medical Technology Report 2017. 2017.