Abstract

Purpose:

Longitudinal studies into the variability of 18F-Flutemetamol uptake are lacking.

Methods/Patients:

Therefore, the current study examined change in 18F-Flutemetamol uptake in 19 non-demented older adults (65 – 82 years old) who were either cognitively intact or had Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) who were scanned twice across 3.6 years.

Results:

Baseline and follow-up composite SUVRs were significantly correlated (0.96, p<0.001). Significant increases in the composite SUVR from baseline to follow-up were observed (p=0.002). For the total sample, the average difference over this time period when using the composite SUVR was 6.8%. Similar results were seen in subsets of the total sample (MCI vs. cognitively intact, amyloid positive vs. negative). Finally, a Reliable Change Index that exceeded ±0.046 SUVR units would indicate a significant change of 18F-Flutemetamol.

Conclusion:

The current results extend the limited literature on longitudinal variability of 18F-Flutemetamol uptake across 3.6 years, which should give clinicians and researchers more confidence in the stability of this amyloid imaging agent in longer therapeutic and prevention trials in cognitive decline in MCI and Alzheimer’s disease.

INTRODUCTION

Noninvasive in vivo imaging of amyloid plaques has been an important advance in the diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [1, 2]. Following 11C Pittsburgh Compound B (PIB), a host of 18F amyloid imaging agents have been developed. One of the more recently FDA-approved 18F agents is 18F-Flutemetamol/Vizamyl [3]. This tracer has been validated in a number of ways. For example, 18F-Flutemetamol uptake has been correlated with autopsy and histopathological findings [4–9]. 18F-Flutemetamol binding has been used to successfully differentiate cognitively intact individuals from those with AD [10–13]. It has also been associated with a variety of cognitive outcome measures [14–16].

While numerous studies have provided evidence supporting the validity of 18F-Flutemetamol amyloid imaging, there has been little work investigating the short- and long-term uptake variability of this imaging agent. Vandenberghe et al. [11] reported on short-term test-retest uptake variability of 18F-Flutemetamol in five patients with AD scanned twice across 7 – 13 days. The mean variability for the cortical composite measure was 1.5% (SD = 0.7), with regional variabilities ranging from 1 – 4%. Across a longer interval (1 – 4 weeks), Miki et al. [17] also reported relatively minimal variability in a composite measure of 18F-Flutemetamol uptake for five patients with AD (1 – 2%).

Despite these short-term investigations into the test-retest variability of 18F-Flutemetamol uptake, longitudinal studies of a longer duration are needed to assess uptake variability and change to further inform clinicians and researchers who might use this amyloid-binding imaging agent to evaluate patients over time or for treatment response assessment. To our knowledge, there have been no such published longitudinal studies on long-term variability or changes of 18F-Flutemetamol uptake. Additionally, the existing studies have only reported on small samples of patients with AD. Therefore, the current study reports on a sample of older adults who were either cognitively intact or had Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) who were scanned twice with 18F-Flutemetamol across 3.6 years. Although the interval between scans was much longer than in prior studies, it was hypothesized that 18F-Flutemetamol uptake would remain relatively stable for both intact and MCI subjects.

METHODS

Participants.

Nineteen older adults (14 females/5 males, mean age=78.3 [SD=6.3] years, mean education=15.9 [SD=3.2] years) were enrolled in this study. These individuals were all recruited from senior centers and independent living facilities to participate in studies on memory and aging. All participants reported to be functionally independent in activities of daily living, and this was corroborated by a knowledgeable informant. Based on objective cognitive testing, the majority of these individuals were classified as cognitively intact (n=13), with the remainder characterized as MCI (n=6) [18], exhibiting at least an amnestic profile. Exclusion criteria for this study included: history of neurological disease known to affect cognition (e.g., stroke, head injury with loss of consciousness of >30 minutes, seizure disorder, demyelinating disorder, etc.); dementia based on DSM-IV criteria; current or past major psychiatric illness (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder); 30-item Geriatric Depression Score >15; history of substance abuse; current use of cholinesterase inhibitors, other cognitive enhancers, antipsychotics, or anticonvulsant medications at the baseline and follow-up visits; history of radiation therapy to the brain; history of significant major medical illnesses, such as cancer or AIDS; and currently pregnant.

Procedures.

The local institutional review board approved all procedures and all participants provided informed consent before data collection commenced. All participants completed a baseline neuropsychological battery designed to characterize their functioning on tests of memory and processing speed, which included the Reading subtest of the Wide Range Achievement Test – IV [19] (premorbid intellect), Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised [20] (verbal memory), Brief Visuospatial Memory Test – Revised [21] (visual memory), Symbol Digit Modalities Test [22] (processing speed), and Trail Making Test Parts A [23] (processing speed) and B (processing speed and executive functioning). Participants were classified as intact if their memory tests scores were no more than 1.5 SDs below their estimated premorbid intellect; they were classified as amnestic MCI if their memory test scores were 1.5 SDs or more below premorbid intellect.

Following baseline cognitive testing, participants underwent 18F-Flutemetamol imaging as described previously [16, 24]. 18F-Flutemetamol was produced under PET cGMP standards and the studies were conducted under an approved Federal Drug Administration Investigational New Drug application. Imaging was performed 90 minutes after the injection of 185 MBq (5 mCi) of 18F-Flutemetamol. The emission imaging acquisition time was approximately 30 minutes. Two different PET scanners were used for imaging in this study, a General Electric (GE) Advance PET scanner and a GE ST PET/CT scanner. We have described previously the reconstructed image comparability between the two scanners [24]. All images were reviewed and interpreted as amyloid positive or negative based on information provided in the current prescribing information [3].

Volumes of interest were automatically generated by the CortexID Suite analysis software (GE Healthcare) [25, 26]. 18F-Flutemetamol binding was analyzed using a regional semi-quantitative technique described by Vandenberghe et al. [11] and refined by Thurfjell et al. [26]. Semi-quantitative regional (prefrontal, anterior cingulate, precuneus/posterior cingulate, parietal, mesial temporal, lateral temporal, occipital, sensorimotor, cerebellar grey matter, and whole cerebellum) and composite standardized uptake value ratios (SUVRs) in the cerebral cortex were generated automatically and normalized to the pons [20]. The software uses a threshold z score of 2.0 to indicate abnormally increased regional amyloid burden that corresponds to a composite SUVR of 0.59 when normalized to the pons, providing a 99.4% concordance with visual assessment [26]. There is no specific age-related “normal” level of binding in the CortexID Suite database to assess age-matched normality. The study images were compared to the intrinsic software database control group as a whole to calculate the z-scores which is highly concordant with clinically negative amyloid scans.

After 3.6 (0.2) years, participants returned to repeat the neuropsychological and amyloid imaging procedures.

Statistical analyses.

Three primary analyses were planned using the total sample: 1) Pearson correlations were calculated between the 18F-Flutemetamol composite at baseline and follow-up, and 2) dependent t-tests comparing baseline to follow-up values on the composite, and 3) longitudinal variability was calculated as indicated in Vanderbeghe [11], which is 100*(SUVRtest − SUVRretest)/( SUVRtest + SUVRretest)/2. In secondary analyses, the primary analyses were repeated on subsets of the total sample (e.g., cognitively intact vs. MCI, amyloid positive vs. negative). Finally, a Reliable Change Index [27] was calculated as (√2s12(1 − r12))*1.645, where s1 = standard deviation at time 1 and r12 = correlation at time 1 and time 2. An alpha value of 0.05 was used for these analyses.

RESULTS

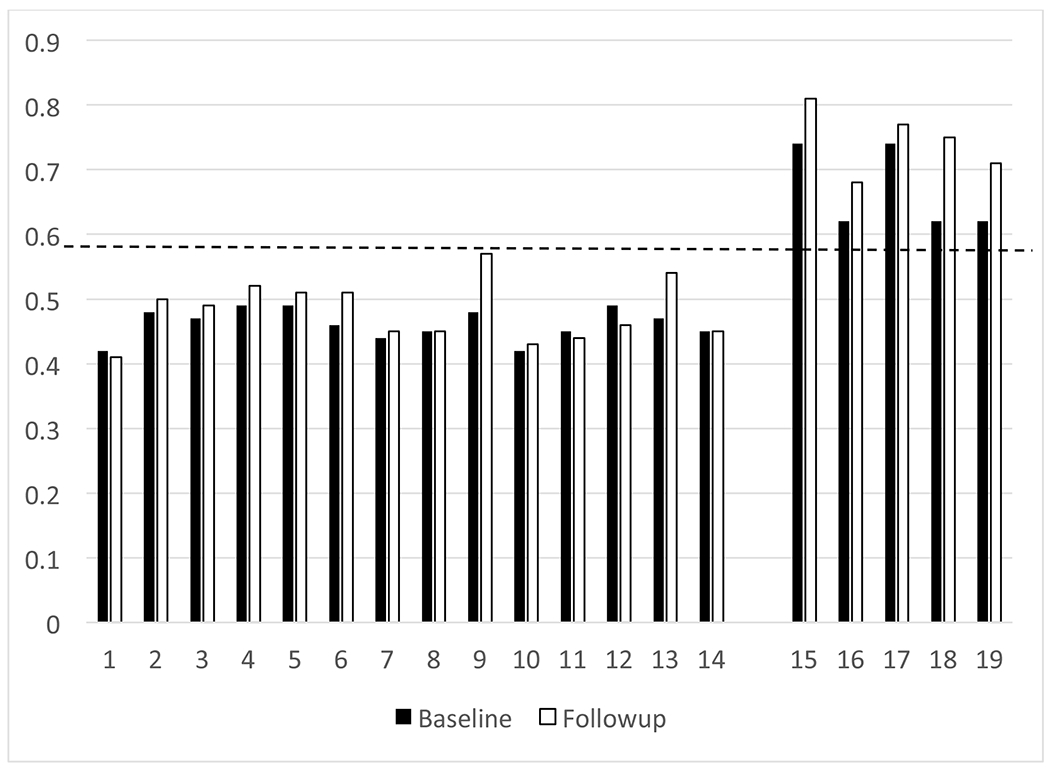

No adverse events were reported during the injection, uptake time, or imaging studies with the imaging agent 18F-Flutemetamol. As noted in Table 1, the baseline mean composite of SUVRs normalized to pons was 0.52 (SD = 0.10). At this initial scanning session, 5 of the 19 were categorized as “positive” for 18F-Flutemetamol uptake, using a cutoff of z-score greater than or equal to 2.0, and 14 were “negative.” After a mean follow-up period of 3.6 years (SD = 0.2, range = 3.2 – 4.0), the follow-up mean composite of SUVRs normalized to pons was 0.55 (SD = 0.13), which are also presented in Table 1. With the follow-up quantitative composite SUVR data (using a cutoff of 0.59), each participant retained their original amyloid status (i.e., 5 “positive” and 14 “negative”). Each participants’ baseline and follow-up SUVRs are presented in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Baseline and follow-up SUVR data.

| Baseline SUVR | Follow-up SUVR | r | Mean variability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | 0.52 (0.10) 0.42 – 0.74 |

0.55 (0.13)* 0.41 – 0.81 |

0.96* | 6.8 % 0 – 19% |

| Cognitively Intact at baseline (n = 13) | 0.49 (0.06) 0.42 – 0.62 |

0.51 (0.09)* 0.41 – 0.71 |

0.95* | 6.1% 0 – 17% |

| MCI at baseline (n = 6) | 0.58 (0.14) 0.45 – 0.74 |

0.64 (0.16)* 0.45 – 0.81 |

0.96* | 8.3% 0 – 19% |

| Amyloid positive at baseline (n = 5) | 0.67 (0.07) 0.62 – 0.74 |

0.74 (0.05)* 0.68 – 0.81 |

0.83 | 10.9% 4 – 19% |

| Amyloid negative at baseline (n = 14) | 0.46 (0.02) 0.42 – 0.49 |

0.48 (0.05)* 0.41 – 0.57 |

0.75* | 5.4% 0 – 17% |

Note. MCI = Mild Cognitive Impairment, r = correlation between baseline and follow-up SUVR values,

= p<0.05.

In columns 2 and 3, the values are mean, standard deviation (in parentheses), and range. Mean variability used the formula in Vandenberghe et al. [11].

Figure 1.

Baseline and follow-up SUVR on each participant.

Note. Y-axis reflects composite SUVR value. X-axis reflects individual participants, grouped by baseline amyloid status. Dashed line reflects the composite SUVR threshold of 0.59.

In the primary analyses of the total sample, the Pearson correlation between baseline and follow-up composite of SUVRs was 0.96, p < 0.001, indicating a strong association between results at each visit. A dependent t-test comparing each individual’s baseline and follow-up composite was statistically significant (t = 3.59, p = 0.002), indicating an overall increase in amyloid binding at follow-up. For the total sample, the average longitudinal variability of the composite was 6.8% (range = 0 – 19%). Regional differences were comparable to the composite and these results can be requested from the first author.

In secondary analyses, the primary analyses were repeated for two subsets: 1) intact vs. MCI, and 2) amyloid positive vs. negative. In participants classified as cognitively intact at baseline, the Pearson correlation between baseline and follow-up composite of SUVRs was 0.95, p < 0.001, and this dependent t-test was statistically significant (t = 2.44, p = 0.03). For the cognitively intact participants, the average longitudinal variability of the composite was 6.1% (range = 0 – 17%). In participants classified as MCI at baseline, the Pearson correlation between baseline and follow-up composite of SUVRs was 0.96 (p = 0.002), the dependent t-test was statistically significant (t = 2.79, p = 0.04), and the average longitudinal variability of the composite was 8.3% (range = 0 – 19%). In participants classified as amyloid positive at baseline, the Pearson correlation between baseline and follow-up composite of SUVRs was 0.83, p = 0.08, the dependent t-test was statistically significant (t = 4.58, p = 0.01), and the average longitudinal variability of the composite was 10.9% (range = 4 – 19%). In participants classified as amyloid negative at baseline, the Pearson correlation between baseline and follow-up composite of SUVRs was 0.75, p = 0.002, the dependent t-test was statistically significant (t = 2.22, p = 0.04), and the average longitudinal variability of the composite was 5.4% (range = 0 – 17%).

Using data from the overall sample, a Reliable Change Index [27] was calculated ((√2s12(1 − r12))*1.645), with s1 = 0.10 and r12 = 0.96. The resulting value of ±0.046 would reflect a 90% confidence interval around the average amount of change in SUVR seen in this sample. Any change beyond ±0.046 would indicate a significant change in 18F-Flutemetamol uptake. Applying this metric back to the current sample, it shows that 14 subjects had increases in their SUVRs (≥+0.046), 2 remained stable within that 90% confidence interval (−0.045 – +0.045), and 3 had decreases in SUVR (≤−0.046).

DISCUSSION

The current study sought to add to the limited literature on longitudinal change and long-term variability of 18F-Flutemetamol uptake by examining a sample of non-demented older adults who were scanned twice with this radiopharmaceutical across 3.6 years. In the total sample of participants with either intact cognition or MCI, there was a very high association between their baseline and follow-up global amyloid burden (r = 0.96), and there was relatively little variability in the uptake of 18F-Flutemetamol across 3.6 years (<7%). Despite this, an overall increase in amyloid binding was observed at follow-up in this sample, even though no participants’ amyloid status switched categories (e.g., “negative” to “positive”). These results would appear to give clinicians and researchers additional confidence about the stability of 18F-Flutemetamol in evaluating in vivo amyloid burden across time.

The current findings are largely consistent with the two studies that have reported short-term test-retest variability of 18F-Flutemetamol. In five patients with AD who were scanned twice across 7 – 13 days, Vandenberghe et al. [11] found a mean variability for a cortical composite measure of 1.5%. Across 1 – 4 weeks, Miki et al. [17] found a mean variability for a cortical composite measure of <3% for five patients with AD. Although our study found slightly higher rates of variability than these two prior studies (<7% vs. <3%), multiple factors likely contribute to these differences. First, the current study examined a less cognitively impaired cohort (intact and MCI) than the prior studies (AD). It is reasonable to hypothesize that amyloid burden may be more stable in those who have already been diagnosed with AD compared to those who are at risk of developing AD. Second, in the current longitudinal study, the retest interval was over 3.5 years, whereas the retest interval in the prior studies was less than 4 weeks. It is rational to suspect that amyloid burden would be more stable over shorter periods of time. Finally, the size of the sample of the current study was three times larger than the other two studies. Although a larger sample may appear more stable, it may also have more variability in SUVR values, which could make it less stable across time.

Other amyloid imaging agents have yielded similar variability estimates as the current study. For example, studies on the variability of 11C Pittsburgh Compound B (PIB) have found relatively minimal amounts of change across short intervals (4.4% variability in posterior cingulate across 20 days [28] using the Vandenberghe calculation; ±10% for most brain regions across 28 days using their own calculation [29], 4.2 – 8.1% across three different outcome parameters [30] using the Vandenberghe calculation). Across longer retest intervals, Engler et al. [31] reported 3 – 7% variability for most regions in 16 subjects with AD retested after 2 years with 11C Pittsburgh Compound B (PIB), with no significant changes in PIB retention from baseline to follow-up. Using 18F-Florbetapir, Joshi et al. [32] reported <1% for variability for 10 patients with AD and 0% variability for 10 controls on a composite measure using the Vandenberghe calculation when they were scanned twice across 4 weeks. In larger samples scanned twice across 2 years, Landau [33] observed 1 – 2% annual mean change in 18F-Florbetapir uptake, even in individuals who were amyloid positive at their baseline scan. Overall, multiple amyloid imaging agents appear to have relatively minimal variability (<10%) across time.

Some discussion of the individual results presented in Figure 1 seems necessary. Visually, it appears that some cases show increases in their SUVR uptake, some remain quite stable, and some show a decrease in uptake across 3.6 years. However, to our knowledge, there are no published studies to provide a frame of reference for the amount of change in the uptake of 18F-Flutemetamol across this period of time. Using the Reliable Change Index [27], which is frequently used in clinical neuropsychology to determine cognitive change across time, a change in SUVR of ±0.046 would reflect a 90% confidence interval around the average amount of change seen in this sample. Based on this confidence interval, any change beyond ±0.046 would indicate a significant change. Using this confidence interval, 14 subjects had increases in their SUVRs, 2 remained stable, and 3 had decreases in SUVR. Such a metric could be used to identify clinically meaningful change in 18F-Flutemetamol uptake across a multi-year period. This metric could also be used to further inform the field about which individuals are more likely to change across time. For example, the baseline 18F-Flutemetamol uptake levels positively correlated with Reliable Change Index scores (r = 0.53, p = 0.02), indicating that the higher baseline SUVRs were related to greater increases in SUVRs across time. This seems quite evident in the 5 cases who had elevated amyloid levels at baseline, as most showed notable increases at their follow-up 18F-Flutemetamol scan.

In additional secondary analyses, we examined longitudinal variability of 18F-Flutemetamol in various subsets of the original sample. For example, the participants classified as cognitively intact at baseline showed very similar correlation and variability values (r = 0.95, variability = 6.1%) to those classified as MCI at baseline (r = 0.96, variability = 8.3%). The similarity between these two groups, who differ in the level of cognitive functioning, is encouraging for clinicians and researchers using this radiopharmaceutical, especially as the drug development and clinical trials are moving towards earlier therapeutic and prevention trials in AD. Our study provides the first data measuring the “natural” change in amyloid burden over multiple years in these target populations, establishing essentially a control reference range against which any observed response to therapeutic intervention can be compared. In the second subset, those classified as amyloid positive at baseline showed slightly higher correlation values and slightly more variability (r = 0.83, variability = 10.9%) than those classified as amyloid negative at baseline (r = 0.75, variability = 5.4%). These slight differences are not particularly surprising given the differences between these two groups in their initial amyloid status. In all four of these subsets (intact, MCI, amyloid positive, amyloid negative), significant increases in amyloid uptake were seen across 3.6 years. Although these increases were relatively small (mean Δ SUVR = 0.02 – 0.07), they were larger in MCI (vs. intact) and amyloid positive (vs. amyloid negative), which meets expectations for these “disease states.”

Despite the new information about the longitudinal stability of 18F-Flutemetamol uptake presented in this study, some limitations should be noted. First, the sample size was relatively small. Nineteen subjects were scanned twice with this tracer. Even though this sample is more than three times larger than the other two studies that examined this topic [11, 17], larger samples would provide better generalizability of the findings. Second, the current study focused on individuals in a pre-dementia state, where amyloid burden is more likely to be changing. Prior studies have documented the reliability/stability of 18F-Flutemetamol amyloid imaging in patients already diagnosed with AD [11, 17], in whom it is expected to be more stable. Third, the retest interval used in the current study averaged 3.6 years, which is much longer than most clinical and research scenarios. Conversely, this interval might be too brief to see the meaningful changes that occur over longer periods of time (e.g., development of amyloid plaques 10 – 20 years before cognitive changes), which could be examined with future studies. Nonetheless, the current results extend the limited literature on the longitudinal variability of 18F-Flutemetamol uptake, which should give clinicians and researchers more confidence in using this amyloid imaging agent for treatment response assessment in therapeutic and prevention trials in MCI and AD.

Acknowledgements:

The project described was supported by research grants from the National Institutes on Aging: R01AG055428. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging or the National Institutes of Health. Support was also provided by GE Healthcare and the Center for Quantitative Cancer Imaging, Huntsman Cancer Institute, University of Utah.

References

- 1.Morris E, et al. , Diagnostic accuracy of (18)F amyloid PET tracers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 2016. 43(2): p. 374–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeo JM, et al. , A systematic review and meta-analysis of (18)F-labeled amyloid imaging in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement (Amst), 2015. 1(1): p. 5–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.GeneralElectricHealthcare. Vizamyl Package Insert. Available from: http://www3.gehealthcare.com/~/media/documents/us-global/products/nuclear-imaging-agents_non-gatekeeper/clinical%20product%20info/vizamyl/gehealthcare-vizamyl-prescribing-information.pdf.

- 4.Leinonen V, et al. , Diagnostic effectiveness of quantitative [(1)(8)F]flutemetamol PET imaging for detection of fibrillar amyloid beta using cortical biopsy histopathology as the standard of truth in subjects with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Acta Neuropathol Commun, 2014. 2: p. 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolk DA, et al. , Association between in vivo fluorine 18-labeled flutemetamol amyloid positron emission tomography imaging and in vivo cerebral cortical histopathology. Arch Neurol, 2011. 68(11): p. 1398–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curtis C, et al. , Phase 3 trial of flutemetamol labeled with radioactive fluorine 18 imaging and neuritic plaque density. JAMA Neurol, 2015. 72(3): p. 287–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong DF, et al. , An in vivo evaluation of cerebral cortical amyloid with [18F]flutemetamol using positron emission tomography compared with parietal biopsy samples in living normal pressure hydrocephalus patients. Mol Imaging Biol, 2013. 15(2): p. 230–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thal DR, et al. , [(18)F]flutemetamol amyloid positron emission tomography in preclinical and symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease: specific detection of advanced phases of amyloid-beta pathology. Alzheimers Dement, 2015. 11(8): p. 975–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salloway S, et al. , Performance of [(18)F]flutemetamol amyloid imaging against the neuritic plaque component of CERAD and the current (2012) NIA-AA recommendations for the neuropathologic diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement (Amst), 2017. 9: p. 25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelissen N, et al. , Phase 1 study of the Pittsburgh compound B derivative 18F-flutemetamol in healthy volunteers and patients with probable Alzheimer disease. J Nucl Med, 2009. 50(8): p. 1251–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vandenberghe R, et al. , 18F-flutemetamol amyloid imaging in Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment: a phase 2 trial. Ann Neurol, 2010. 68(3): p. 319–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duara R, et al. , Amyloid positron emission tomography with (18)F-flutemetamol and structural magnetic resonance imaging in the classification of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement, 2013. 9(3): p. 295–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowe VJ, et al. , Comparison of [(18)F]Flutemetamol and [(11)C]Pittsburgh Compound-B in cognitively normal young, cognitively normal elderly, and Alzheimer’s disease dementia individuals. Neuroimage Clin, 2017. 16: p. 295–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quenon L, et al. , Prediction of Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test Performance Using Volumetric and Amyloid-Based Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc, 2016. 22(10): p. 991–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammers DB, et al. , Relationship between (18)F-Flutemetamol uptake and RBANS performance in non-demented community-dwelling older adults. Clin Neuropsychol, 2017. 31(3): p. 531–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duff K, et al. , Short-Term Practice Effects and Amyloid Deposition: Providing Information Above and Beyond Baseline Cognition. J Prev Alzheimers Dis, 2017. 4(2): p. 87–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miki T, et al. , Brain uptake and safety of Flutemetamol F 18 injection in Japanese subjects with probable Alzheimer’s disease, subjects with amnestic mild cognitive impairment and healthy volunteers. Ann Nucl Med, 2017. 31(3): p. 260–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winblad B, et al. , Mild cognitive impairment--beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med, 2004. 256(3): p. 240–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilkinson GS, & Robertson GJ, WRAT 4: Wide Range Achievement Test; professional manual. 2006: Psychological Assessment Resources, Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brandt J and Benedict RHB, Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised. 1997, Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benedict RHB, Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised. 1997, Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith A, Digit Symbol Modalities Test. 1982, Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reitan RM, Trail Making Test: Manual for administration and scoring. 1992: Reitan Neuropsychology Laboratory. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duff K, et al. , Amyloid deposition and cognition in older adults: the effects of premorbid intellect. Arch Clin Neuropsychol, 2013. 28(7): p. 665–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.GeneralElectricHealthcare. CortexID Suite website. Available from: http://www3.gehealthcare.com/en/products/categories/advanced_visualization/applications/cortexid.

- 26.Thurfjell L, et al. , Automated quantification of 18F-flutemetamol PET activity for categorizing scans as negative or positive for brain amyloid: concordance with visual image reads. J Nucl Med, 2014. 55(10): p. 1623–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobson NS and Truax P, Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol, 1991. 59(1): p. 12–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Price JC, et al. , Kinetic modeling of amyloid binding in humans using PET imaging and Pittsburgh Compound-B. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2005. 25(11): p. 1528–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopresti BJ, et al. , Simplified quantification of Pittsburgh Compound B amyloid imaging PET studies: a comparative analysis. J Nucl Med, 2005. 46(12): p. 1959–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edison P, et al. , Can target-to-pons ratio be used as a reliable method for the analysis of [11C]PIB brain scans? Neuroimage, 2012. 60(3): p. 1716–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engler H, et al. , Two-year follow-up of amyloid deposition in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Brain, 2006. 129(Pt 11): p. 2856–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joshi AD, et al. , Performance characteristics of amyloid PET with florbetapir F 18 in patients with alzheimer’s disease and cognitively normal subjects. J Nucl Med, 2012. 53(3): p. 378–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landau SM, et al. , Measurement of longitudinal beta-amyloid change with 18F-florbetapir PET and standardized uptake value ratios. J Nucl Med, 2015. 56(4): p. 567–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]