Abstract

Coinfection of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) with tuberculosis (TB) has not been previously reported. Here, we present 2 cases with both MERS-CoV and pulmonary TB. The first case was a 13-year-old patient who was admitted with a 2-month history of fever, weight loss, night sweats, and cough. The second patient was a 30-year-old female who had a 4-week history of cough associated with shortness of breath and weight loss of 2 kg. The 2 patients were diagnosed with pulmonary TB and had positive MERS-CoV. Both patients were discharged to complete their therapy for TB at home. It is likely that both patients had pulmonary TB initially as they had prolonged symptoms and they subsequently developed MERS-CoV infection. It is important to carefully evaluate suspected MERS-CoV patients for the presence of other infectious diseases, such as TB, especially if cohorting is done for suspected MERS-CoV to avoid nosocomial transmission.

Keywords: Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, Tuberculosis, Coinfection, MERS-CoV

Introduction

Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) was first discovered in Saudi Arabia in 2012 [1]. As of January 26, 2017, a total of 1,888 laboratory-confirmed cases of MERS-CoV infection, including at least 670 related deaths, have been reported to the WHO [2]. Clinical presentations, diagnosis, and laboratory findings have been previously described [3]. As highlighted in the previous studies, none of the presenting symptoms helped distinguish patients with MERS-CoV infection from a patient presenting with influenza-like illness [4, 5]. Even with access to a full viral panel on all influenza-like illness patients and with evidence of influenza virus as the etiology, MERS-CoV cannot be ruled out. A previous study showed that 1 out of 5 patients with MERS-CoV had influenza coinfection [6]. Investigation of the initially described 47 MERS-CoV patients showed no coinfection with MERS-CoV as microbiological investigations excluded bacterial pathogens associated with community-acquired pneumonia [7]. Coinfection of MERS-CoV with other viruses such as influenza has been reported [8].

From April 2014 to November 2016, 295 confirmed MERS-CoV cases were admitted to Prince Mohamed Bin Abdulaziz Hospital (PMAH), a MERS-CoV-designated hospital in Riyadh, the capital city of Saudi Arabia [5]. To our knowledge, the coinfection of MERS-CoV and Mycobacterium tuberculosis has not been reported previously. Here, we present 2 cases of coinfection of MERS-CoV and pulmonary tuberculosis (TB).

Methods

Patient Data

For each patient, we extracted the date of admission, gender, age, results and dates of MERS-CoV testing, and outcomes. This included the initial laboratory data: white blood cell count (WBC), hemoglobin, platelets, creatinine, albumin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and initial chest X-ray results. The study complied with institutional ethical guidelines.

MERS-CoV Testing

Nasopharyngeal swabs were tested for MERS-CoV using real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction as described previously [7, 9]. The test amplified both the upstream E protein (upE gene) and ORF1a. A positive case was considered if both assays were positive and controls were negative, as described previously [7]. The specimens were submitted to testing at the Saudi Ministry of Health MERS-CoV regional laboratory.

Case 1

A 13-year-old girl was admitted with a 2-month history of fever, weight loss, night sweats, and cough. She had a history of contact with a pulmonary TB patient. Four days prior to her presentation she had worsening respiratory symptoms. No history of contact with camels or a MERS-CoV patient was reported.

On examination she looked ill and cachectic, with respiratory distress. She was febrile, with a temperature of 39°C, her blood pressure was 100/59, respiration rate was 38, SPO2 measured 95%, and her weight was 40 kg. There was no lymphadenopathy. A chest examination revealed bronchial breathing and bilateral crepitations.

Chest X-rays showed diffuse multinodular infiltration consistent with miliary TB (Fig. 1). A CT scan of the chest and abdomen showed multiple pulmonary nodules randomly distributed in both lungs. Multiple areas of consolidation, especially within the left upper lobe, were also noted. Multiple cystic areas probably representing cystic bronchiectasis changes were seen bilaterally in the upper lobes. There were necrotic mediastinal and enlarged hilar lymph nodes.

Fig. 1.

Diffuse multinodular infiltration consistent with miliary TB.

A nasopharyngeal swab collected upon presentation was positive for MERS-CoV and negative for influenza, and a repeated swab after 48 h was negative for MERS-CoV. A tuberculin skin test was 10 mm and sputum AFB smears were negative, but gastric aspirate was positive for M. tuberculosis by PCR and mycobacterium culture was positive for M. tuberculosis. During hospitalization, the patient experienced respiratory distress and hypoxia requiring intensive care admission for observation. Isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, and rifampicin were started. The patient was discharged in a stable condition after hospitalization for 3 weeks to complete anti-TB therapy at home.

Case 2

A 30-year-old Filipino female nurse had unprotected exposure to a patient with MERS-CoV on May 15, 2015. She was subsequently quarantined for 14 days in hospital and 2 nasopharyngeal swabs for MERS-CoV were negative. A month later, she traveled to the Philippines. Two weeks after her arrival in the Philippines, she manifested symptoms of dry cough and shortness of breath, and she took amoxicillin with no improvement. On August 7, she returned to Saudi Arabia, where she was evaluated for 4 weeks from August 12 for dry cough associated with shortness of breath and a weight loss of 2 kg. She had no history of contact with TB patients and no history of recent contact with an MERS-CoV patient.

On examination, her (oral) temperature was 37°C, blood pressure was 133/88, and SpO2 measured 94%. A chest examination revealed crepitation in the left upper lobe. Laboratory data showed: WBC 6.8 ×109/L, neutrophils 68%, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 90 mm/h, and C-reactive protein 0.39 mg/L.

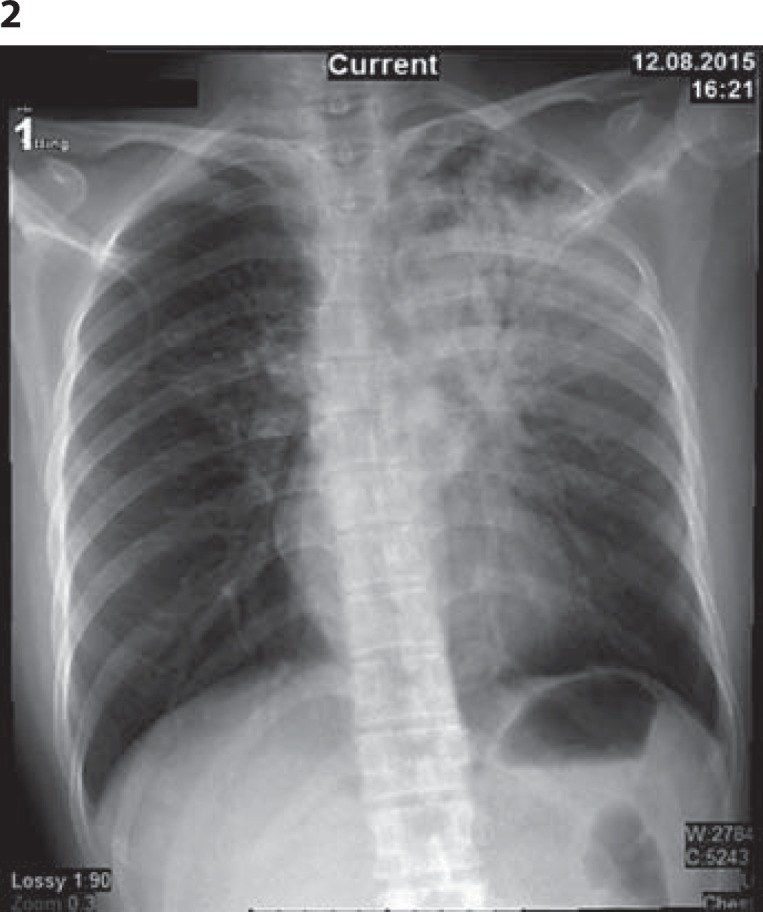

A chest X-ray showed nonhomogenous opacity involving most of the left lung, most prominent in the upper and middle left lung zones (Fig. 2). A nasopharyngeal swab collected upon presentation was positive for MERS-CoV and negative for influenza. A repeated swab after 48 h was negative for MERS-CoV. Sputum acid-fast bacillus (AFB) PCR and AFB smear were positive, but TB culture was negative. The patient was treated with isoniazid, ethambutol, pyrazinamide, and rifampicin.

Fig. 2.

Chest X-ray showing a nonhomogenous opacity involving most of the upper and middle left lung zones.

Discussion

The presentation of these 2 patients is of particular interest due to the coinfection with MERS-CoV and pulmonary TB. We are not aware of any previous such report. Coinfection of MERS-CoV patients with influenza A, parainfluenza, herpes simplex, Streptococcus pneumoniae, herpes simplex virus type 1, and rhinovirus RNA 14 have previously been reported [8, 10, 11]. Coinfection with M. tuberculosis is of particular importance as the diagnosis of TB might be overlooked and shadowed by concern about MERS-CoV infection, as occurred during the SARS outbreak [12]. One patient contracted SARS when she was cohorted with SARS patients, although she initially had TB [12]. In another report, a healthcare worker had healthcare-associated SARS infection and was diagnosed with pulmonary TB, while 2 other patients were known to have pulmonary TB and had a superinfection with SARS after contact with other hospitalized SARS patients [13]. Another 2 patients had pulmonary TB after recovery from SARS [14]. In this report, the first patient was coinfected with MERS-CoV and pulmonary TB, and might have been infected with both as the M. tuberculosis culture was negative. Both MERS-CoV and TB may cause immune suppression and augment the infection of each other, as was described with SARS and TB [13]. It is important to carefully evaluate suspected MERS-CoV for the presence of other infectious diseases, especially TB, if cohorting is done for suspected MERS-CoV to avoid the nosocomial transmission of TB, as was described with SARS [15]. In the current cases, it is likely that both patients initially had pulmonary TB as they had prolonged symptoms, and they subsequently developed MERS-CoV infection.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus ADME, Fouchier RAM. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) http://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. Managing MERS-CoV in the healthcare setting. Hosp Pract. 2015;43:158–163. doi: 10.1080/21548331.2015.1074029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Tawfiq JA, Hinedi K, Ghandour J, Khairalla H, Musleh S, Ujayli A, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a case-control study of hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:160–165. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohd HA, Memish ZA, Alfaraj SH, McClish D, Altuwaijri T, Alanazi MS, et al. Predictors of MERS-CoV infection: a large case control study of patients presenting with ILI at a MERS-CoV referral hospital in Saudi Arabia. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2016;14:464–470. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yavarian J, Rezaei F, Shadab A, Soroush M, Gooya MM, Azad TM. Cluster of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections in Iran, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:362–364. doi: 10.3201/eid2102.141405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Assiri A, Al-Tawfiq JA, Al-Rabeeah AA, Al-Rabiah FA, Al-Hajjar S, Al-Barrak A, et al. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:752–761. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alfaraj SH, Al-Tawfiq JA, Alzahrani NA, Altwaijri TA, Memish ZA. The impact of co-infection of influenza A virus on the severity of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Infect. 2017;74:521–523. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corman VM, Müller MA, Costabel U, Timm J, Binger T, Meyer B, et al. Assays for laboratory confirmation of novel human coronavirus (hCoV-EMC) infections. Euro Surveill. 2012;17:49. doi: 10.2807/ese.17.49.20334-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization . WHO guidelines for investigation of cases of human infection with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) 2013. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/MERS_CoV_investigation_guideline_Jul13.pdf (accessed January 17, 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drosten C, Seilmaier M, Corman VM, Hartmann W, Scheible G, Sack S, et al. Clinical features and virological analysis of a case of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:745–751. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70154-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong C-Y, Wong K-Y, Law TSG, Shum T-T, Li Y-K, Pang W-K. Tuberculosis in a SARS outbreak. J Chin Med Assoc. 2004;67:579–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu W, Fontanet A, Zhang P-H, Zhan L, Xin Z-T, Tang F, et al. Pulmonary tuberculosis and SARS, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:707–709. doi: 10.3201/eid1204.050264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Low JGH, Lee CC, Leo YS, Guek-Hong Low J, Lee C-C, Leo Y-S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome and pulmonary tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:e123–e125. doi: 10.1086/421396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for. Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Nosocomial transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis found through screening for severe acute respiratory syndrome - Taipei, Taiwan, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:321–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]