Abstract

Objective

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is caused by a new coronavirus. Genomic sequence analysis will provide the molecular epidemiology and help to develop vaccines.

Methods

We developed a rapid method to amplify and sequence the whole SARS-CoV genome from clinical specimens. The technique employed one-step multiplex RT-PCR to amplify the whole SARS-CoV genome, and then nested PCR was performed to amplify a 2-kb region separately. The PCR products were sequenced.

Results

We sequenced the genomes of SARS-CoV from 3 clinical specimens obtained in Taiwan. The sequences were similar to those reported by other groups, except that 17 single nucleotide variations and two 2-nucleotide deletions, and a 1-nucleotide deletion were found. All the variations in the clinical specimens did not alter the amino acid sequence. Of these 17 sequenced variants, two loci (positions 26203 and 27812) were segregated together as a specific genotype-T:T or C:C. Phylogenetic analysis showed two major clusters of SARS patients in Taiwan.

conclusion

We developed a very economical and rapid method to sequence the whole genome of SARS-CoV, which can avoid cultural influence. From our results, SARS patients in Taiwan may be infected from two different origins.

Key Words: Multiplex RT-PCR; SARS, genomic sequence analysis; SARS, Taiwan; SARS-CoV genome; SARS-CoV, infection origin; Severe acute respiratory syndrome

Introduction

An atypical pneumonia with high contagiousness first appeared in the Guangdong Province of the People's Republic of China in November 2002, which infected 792 cases and caused 31 deaths. This disease spread to Hong Kong first, and caused an outbreak in many countries including Vietnam, Canada, Singapore, Taiwan and other countries. Almost 9,000 individuals have been infected and over 900 have died from the disease since February 2003 [1]. This new and deadly syndrome was first brought to the attention of the World Health Organization (WHO) by Dr. Carlo Urbani, and was named as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) [2]. The pathogenesis of SARS is believed to be a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV), which was first found by Peiris et al. [3] in Hong Kong and was confirmed by other groups [4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. The analysis of genomic sequences showed that the virus is different from previously known coronaviruses [9, 10, 11], and serological studies also confirmed that the virus has not been found in humans [12].

The Coronaviridae family is a diverse group of large, enveloped and positive-stranded RNA viruses, and these viruses may cause respiratory and enteric infections in humans and animals. The previously known human coronaviruses are frequent causes of the common cold. Life-threatening pneumonia caused by coronaviruses is uncommon. Generally speaking, the genome of coronavirus is the largest (about 30 kb in length) found in any RNA viruses, which encodes 23 putative proteins, including 4 major structure proteins: nucleocapsid (N), spike (S), membrane (M) and envelope (E) proteins. The N, S and M mature proteins contribute to generating the host immune response [13, 14]. Similarly, the genome of SARS-CoV is a 29729-nucleotide with polyadenylated RNA and about 41% GC content. The genomic organization of SARS-CoV is similar to that of a typical coronavirus, containing the characteristic gene order (5′-replicase, spike, envelope, membrane, and nucleocapsid-3′) and short untranslated regions at both termini [9, 10, 11].

The RNA viruses have high rates in genetic mutations, resulting in evolution of new viral strains and escaping from host defenses [15]. It is very important to understand the mutation rate of the SARS virus spreading through the population for the development of effective vaccines. Meanwhile, several studies have shown that adaptation of a virus to non-natural host cells induces genetic changes in viral genome, and these culture-mediated mutations may produce bias and affect evolutionary studies [16, 17, 18, 19, 20]. In order to avoid these causations, we sequenced the entire SARS-CoV directly using clinical specimens. Using these approaches, we were able to analyze the origin of SARS-CoV infection more accurately.

Materials and Methods

Patients

We collected clinical specimens including nasal and pharyngeal swabs, blood and stool from 3 SARS patients. All patients fitted the WHO definition of being probable SARS cases: fever of 38° or higher, respiratory symptoms, hypoxia, chest radiograph changes suggestive of pneumonia, and history of close contact with SARS patients. The clinical features of 3 cases are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

The clinical features of 3 SARS patients

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 56 | 44 | 26 |

| Sex | M | M | F |

| Temperature on admission, ° | 38.5 | >38 | >38 |

| WBC/μl | 6,760 | 5,360 | 4,120 |

| Lymphocytes, % | 27 | 19.4 | 28.2 |

| Platelets/μl | 126×103 | 125×103 | 190×103 |

| LDH, IU/l | 197 | 116 | 266 |

| GOT, IU/l | 66 | 116 | 266 |

| GPT, IU/l | 70 | 197 | 188 |

| Chest radiograph | Accentuation of bronchovascular marking | Pneumonia left lower lobe | Pneumonia right lower lobe |

| Co-morbidities | α-thal-1 | DM, chronic hepatitis | Nil |

| Outcome | Death | Survived | Survived |

Methods

Total RNA was extracted from the nasopharyngeal samples of the patients using a commercial kit (QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kits, Qiagen Inc., Calif., USA). For RT-PCR analysis of SARS-CoV, the upstream primer 5′-CTAACATGCTTAGGATAATGG-3′ and the downstream primer 5′-CAGGTAAGCGTAAAACTCATC-3′ were used to amplify part of polymerase gene, the methods used were identical to Ksiazek et al. [7].

In order to have enough PCR products of SARS-CoV genome for sequencing, we utilized a multiplex one-step RT-PCR method to amplify the entire genome followed by nested PCR to separately amplify each region of the genome. The strategy is shown in figure 1. The PCR products were then purified and sequenced. The whole SARS-CoV genome was amplified in two reactions (the primers used are shown in table 2) using a multiplex one-step RT-PCR method; the reaction T1 amplified 8 regions of the genome, which are nucleotides (nt) 29-2,194, 3,852-6,070, 7,841-10,050, 11,767-14,164, 15,948-18,119, 19,836-22,177, 23,771-25,864, and 27,551-29,700, respectively; the reaction T2 amplified 7 regions including nt 1,941-4,058, 5,908-8,044, 9,869-12,006, 14,021-16,129, 17,804-20,040, 21,956-23,961, and 25,647-27,794, respectively. The PCR products of T1 were subjected to nested PCR amplification using primer pairs t1, t3, t5, t7, t9, t11, t13, and t15 separately, and T2 products were amplified in a different reaction using primer pair t2, t4, t6, t8, t10, t12 and t14, respectively. The primers of t1, t2, t3, t4…. t15 are shown in table 3.

Fig. 1.

The strategy of sequencing analysis of SARS-CoV from clinical specimens. We used two separate multiplex RT-PCR (one contains 8 pairs of primers (T1), and the other contains 7 pairs of primers (T2)) to amplify the whole SARS-CoV genome. The PCR products were used as templates for 15 nested PCRs (t1, t2,t3…. t15) to amplify a 2-kb region, respectively, to ensure the whole SARS-CoV was sequenced. The 15 nested PCR products were further sequenced and analyzed.

Table 2.

The primers used for multiplex RT-PCR

| Reaction | Sequences | Locations (nt) |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction T1 | 5′-GCCAACCAACCTCGATCTCTTG-3′ (F) | 29-50 |

| 5′-CCTTGAGAAATTCAACTCCTGC-3′(R) | 2,194-2,173 | |

| 5′-TGTCGTACAGAAGCCTGTCG-3′ (F) | 3,852-3,871 | |

| 5′-ATGTGACAGATAGCTCTCGT-3′ (R) | 6,070-6,051 | |

| 5′-GCGACGAGTCTGCTTCTAAG-3′ (F) | 7,841-7,860 | |

| 5′-ACAGGTTACTTGTACCATGC-3′ (R) | 10,050-10,031 | |

| 5′-GTACAGTCTAAAATGTCTGACG-3′ (F) | 11,767-11,788 | |

| 5′-AGTGGTTTTGCGAGATCAGC-3′ (R) | 14,164-14,145 | |

| 5′-GTGTCACTGGCTATTGATGC-3′ (F) | 15,948-15,967 | |

| 5′-GGTCATGTCCTTTGGTATGC-3′ (R) | 18,119-18,100 | |

| 5′-GTATCTACAATAGGTGTCTGC-3′ (F) | 19,836-19,856 | |

| 5′-GTAATGTTAATACCAAGAGGC-3′ (R) | 22,177-22,157 | |

| 5′-ACGTGAAGTGTTCGCTCAAG-3′ (F) | 23,771-23,790 | |

| 5′-GTCTTTAACACCTGAGTGCC-3′ (R) | 25,864-25,845 | |

| 5′-TCAACAAGAGCTCTACTCGC-3′ (F) | 27,551-27,570 | |

| 5′-CACATGGGGATAGCACTACT-3′ (R) | 29,700-29,681 | |

| Reaction T2 | 5′-TCCTGATTTGCAAAGAGCAGC-3′ (F) | 1,941-1,962 |

| 5′-TCACCTACCATGTAAGGTGC-3′ (R) | 4,058-4,039 | |

| 5′-GCTTACTATACAGAGCAGCC-3′ (F) | 5,908-5,927 | |

| 5′-GAGCTGTAGCAACAAGTGCC-3′ (R) | 8,044-8,025 | |

| 5′-GCTATCGTGAAGCAGCTTGC-3′ (F) | 9,869-9,888 | |

| 5′-GTTATCGAGCATTTCCTCGC-3′ (R) | 12,006-11,987 | |

| 5′-CGATTTCGGTGATTTCGTAC-3′ (F) | 14,021-14,040 | |

| 5′-AACTCAGGTTCCCAGTACCG-3′ (R) | 16,129-16,110 | |

| 5′-CACACAAACTACTGAAACAGC-3′ (F) | 17,804-17,824 | |

| 5′-CATTGACGCTAGCTTGTGCT-3′ (R) | 20,040-20,021 | |

| 5′-TGCATTTAATTGCACTTTCGAG-3′ (F) | 21,956-21,977 | |

| 5′-CTAGGCATTCGCCATATTGC-3′ (R) | 23,961-23,942 | |

| 5′-GTTGGCTTTGTTGGAAGTGC-3′ (F) | 25,647-25,666 | |

| 5′-CAATGAGAAGTTTCATGTTCG-3′ (R) | 27,794-27,774 | |

nt = Nucleotide; F = forward primer; R = reverse primer.

Table 3.

The SARS-CoV primers used for nested-PCR

| Name | Sequences | Location (nt) |

|---|---|---|

| t1 | 5′-GTAGATCTGTTCTCTAAACG-3′ (F) | 50-69 |

| 5′-TCCATTCAAAGATAGGCCTG-3′ (R) | 2,155-2,136 | |

| t2 | 5′-GTCATTACGTCTTGTCGACG-3′ (F) | 1,992-2,001 |

| 5′-GTTCTGAGAATCATGGTAAACC-3′ (R) | 3,999-3,978 | |

| t3 | 5′-TGAGGTTACCACAACACTGG-3′ (F) | 3,903-3,922 |

| 5′-GAAGCTGGCTTTGTGAAGCC-3′ (R) | 6,050-6,031 | |

| t4 | 5′-CTCAACCATTACCAAATGCG-3′ (F) | 5,945-5,964 |

| 5′-AGTACTATCTCCAACGTCTG-3′ (R) | 7,947-7,928 | |

| t5 | 5′-CTACAGTCAGCTGATGTGCC-3′ (F) | 7,875-7,894 |

| 5′-ACCACTCTGCAGAACAGCAG-3′ (R) | 9,990-9,971 | |

| t6 | 5′-GACTTTAGCAACTCAGGTGC-3′ (F) | 9,913-9,932 |

| 5′-GAAACCATCTTCTCGAAAGC-3′ (R) | 11,933-11,914 | |

| t7 | 5′-GTGCACATCTGTGGTACTGC-3′ (F) | 11,793-11,802 |

| 5′-AAGTGAGGATGGGCATCAGC-3′ (R) | 14,109-14,090 | |

| t8 | 5′-AGGCTGCGGAGTTCCTATTG-3′ (F) | 14,051-14,060 |

| 5′-CAACATGTGGCCAGTAAGCT-3′ (R) | 16,070-16,051 | |

| t9 | 5′-CATCCTAATCAGGAGTATGC-3′ (F) | 15,984-16,003 |

| 5′-TGTAATGTAGCCACATTGCG-3′ (R) | 17,968-17,949 | |

| t10 | 5′-GTCAACCGCTTCAATGTGGC-3′ (F) | 17,838-17,857 |

| 5′-ACCTTTGACTGAACCTTCTG-3′ (R) | 20,000-19,981 | |

| t11 | 5′-CAAGAAACCTACTGAGAGTGC-3′ (F) | 19,874-19,894 |

| 5′-CCAGAAGGTAGATCACGAAC-3′ (R) | 22,126-22,107 | |

| t12 | 5′-CATATCTGATGCCTTTTCGC-3′ (F) | 21,980-21,999 |

| 5′-TCATGAAGCCAGCATCAGCG-3′ (R) | 23,940-23,921 | |

| t13 | 5′-GGTCTTTTATTGAGGACTTGC-3′ (F) | 23,881-23,901 |

| 5′-TGCCGTCACCTTCAGTAACG-3′ (R) | 25,790-25,771 | |

| t14 | 5′-CCAACTACTTTGTTTGCTGGC-3′ (F) | 25,695-25,715 |

| 5′-TCTAGATCCTGGATTTCGAG-3′ (R) | 27,750-27,731 | |

| t15 | 5′-CTCATTGTTGCTGCTCTAGT-3′ (F) | 27,579-27,598 |

| 5′-TAGGGCTCTTCCATATAGGC-3′ (R) | 29,662-29,643 |

nt = Nucleotide; F = forward primer; R = reverse primer.

The multiplex one-step RT-PCR was performed using a commercial kit and the procedure used was recommended by the manufacturer (Qiagen One-Step RT-PCR Kit, Qiagen Inc.). Briefly, 50 μl of reaction solution contains 1-2 μl of RNA solution from the clinical extract, 0.6 μM each of primers, 1 × buffer, 0.6 mM of each dNTP, 3 μl enzyme mix, 6 units Rnase inhibitor. Sample mixtures were placed in a thermal cycler with a temperature at 45° for 30 min, and then incubated at 95° for 15 min before PCR amplification. The PCR amplification consisted of 3 steps including denaturation at 94° for 10 s, annealing at 50 or 54° for 1 min, and extension at 68° for 2.5 min. The 3 steps were repeated for 40 cycles. The nested PCR was performed as follows: 50 μl of reaction solution contains 1 μl of multiplex PCR product, 0.2 μM of each nested PCR primer, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, 1 × Taq buffer, and 1 unit Taq polymerase. The PCR condition included denaturation at 94° for 1 min, annealing at 56° for 1 min, and extension at 72° for 2 min, and these 3 steps were repeated for 35 cycles. The PCR products were resolved on agarose gels, and the proper PCR fragments were excised from gels and then purified using a commercial kit (Qiaex II Gel Extraction Kit, Qiagen Inc.). DNA sequencing was performed using the di-deoxy chain termination method as described in Big Dye™ Terminator cycle sequencer and using an ABI 310 machine (Applied Biosystems Inc., Calif., USA). The primers used for sequencing will be provided on request. Phylogenetic analysis of the SARS-CoV genomes was carried out by ClustalW (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/index.html).

Results

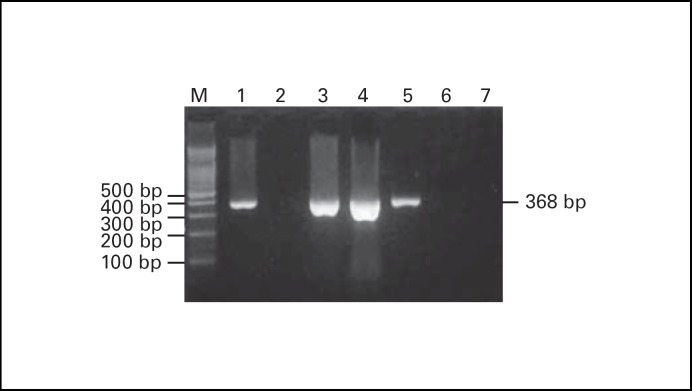

RT-PCR analytic strategy for SARS-CoV is shown in figure 1. The PCR product of SARS-CoV is a fragment of 368 bp using specific primers (fig. 2). Among 87 cases of SARS suspects examined, 3 were positive for the SARS-CoV. These 3 cases were further used for sequencing analysis of entire genomes.

Fig. 2.

The results of RT-PCR analysis of SARS-CoV are shown. The positive case had a PCR fragment of 368- bp. Lane 1 is a positive control; lane 2 is a negative control; lanes 3-5 are the 3 positive cases collected in Taichung, Taiwan; lanes 6 and 7 are negative cases. M = 100-bp ladder markers.

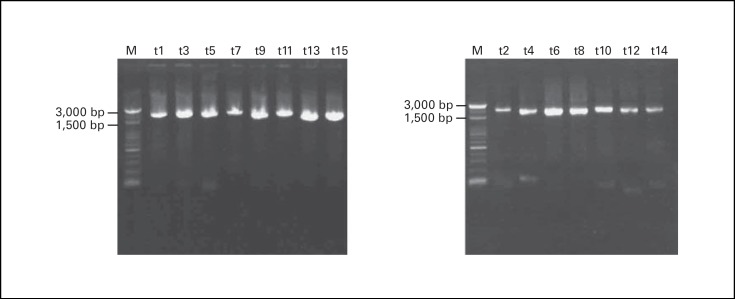

The whole SARS-CoV genome was amplified by multiplex RT-PCR in two separate reactions, followed by 15 different nested PCRs to amplify a 2-kb fragment in each reaction that cover the whole SARS-CoV genome (fig. 3). These 15 nested PCR products were subjected for direct sequencing. The results were submitted to GenBank, and the accession numbers are AY348314 for TC3, AY338175 for TC2 and AY338174 for TC1.

Fig. 3.

The results of nested PCR analysis of a 2-kb region in 15 different reactions, which cover the whole SARS-CoV genome, are shown. The representative markers of t1,t2…. t15 are similar to figure 1.

The genomic sequences of these clinical specimens were similar to those reported from other groups. We compared those genomic and found there were 20 differences, which are 17 single nucleotide variations, two 2-nucleotide deletions and a 1-nucleotide deletion (table 4). We further compared the complete genomic sequences of four clinical specimens with the complete genomic sequences of three cultural isolates in Taiwan. The differences are shown in table 5. In total, there were 11 single nucleotide sequence variations, and one deletion of two nucleotides in the non-coding region. Of the 11 base substitutions, 9 did not alter the original amino acid coding, and the other 2 changed the amino acid sequence. The two missense mutations were all located at the M protein coding area, which were Cys 27 Phe for nt 26477 G→T, and Ala 68 Val for nt 26600 C→T, and appeared only in the cultural isolates. In addition, the two-base deletion mutations were found in the cultural isolates. Of the 11 variants in these samples, two loci (positions 26,203 and 27,812) were identified, and they were segregated together as a specific genotype-T:T or C:C (table 6). The C:C genotype was linked to infection originated at the Amoy Garden in Hong Kong; the T:T genotype was linked to infection acquired from Hoping Hospital in Taipei, Taiwan.

Table 4.

The sequence variants of SARS-CoV in Taiwan area

| Origin | Location (nt) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,782 | 3,165 | 3,852 | 8,160 | 11,493 | 13,098 | 13,347 | 16,325 | 19,361 | 20,083 | 21,581 | 25,652 | 26,203 | 26,477 | 26,600 | 26,615 | 27,167 | 27,168 | 27,808 | 27,809 | 27,812 | 28,302 | ||

| TWC2 | T | A | C | C | T | C | C | A | T | A | C | C | C | G | C | A | A | T | T | T | C | C | |

| TWC3 | C | A | C | C | T | C | C | A | T | A | C | C | C | G | C | A | A | T | T | T | C | C | |

| TWY | C | A | C | C | T | C | T | A | T | A | C | C | T | G | C | A | A | T | T | T | T | C | |

| TWS | C | A | C | C | T | C | C | A | T | A | T | C | T | G | C | A | A | T | T | T | T | C | |

| TWK | C | A | C | C | T | C | C | A | T | A | C | T | T | G | C | A | A | T | T | T | T | T | |

| TWJ | C | A | C | C | T | C | C | A | C | - | C | T | T | G | C | A | - | - | T | T | T | C | |

| TWH | T | A | C | C | T | C | C | A | T | A | C | C | C | G | C | A | A | T | T | T | C | C | |

| TC1 | C | A | C | C | T | C | C | A | T | A | C | C | C | G | C | A | A | T | T | T | C | C | |

| TC2 | C | A | C | T | T | T | C | A | T | A | C | C | T | G | C | A | A | T | T | T | T | C | |

| TC3 | C | A | C | C | T | C | C | A | T | A | C | C | T | G | C | C | A | T | T | T | T | C | |

| TWC | C | A | T | C | C | C | C | G | T | A | C | C | C | T | T | A | A | T | - | - | C | C | |

| TW1 | C | G | T | C | C | C | C | A | T | A | C | C | C | T | C | A | A | T | T | T | C | C | |

TC1 (clinical specimen) and TWC (cultural specimen) is the first case in Taiwan area; TC2 and TC3 from mid-Taiwan area; TW1, TWC2, TWC3, TWY, TWS, TWK, TWJ and TWH from northern part of Taiwan.

Table 5.

Comparison of the sequence variants between cultural isolates and clinical specimens in Taiwan area

| Samples | Location (nt) | ||||||||||

| 1,782 | 3,165 | 3,852 | 8,160 | 11,493 | 13,098 | 16,325 | 26,203 | 26,477* | 26,600* | 27,812 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical specimen | |||||||||||

| TC1 | C | A | C | C | T | C | A | C | G | C | C |

| TC2 | C | A | C | T | T | T | A | T | G | C | T |

| TC3 | C | A | C | C | T | C | A | T | G | C | T |

| TWC3 | C | A | C | C | T | C | A | C | G | C | C |

| Cultural isolates | |||||||||||

| TWC+ | C | A | T | C | C | C | G | C | T | T | C |

| TWC2 | T | A | C | C | T | C | A | C | G | C | C |

| TW1 | C | G | T | C | C | C | A | C | T | C | C |

The base substitution causes amino acid change. nt 26,477 G→T (Cys 27 Phe, M protein); nt 26,600 C→T (Ala 681/Va1, M protein). + A two-base deletion (TT) at 27,808-27,809 was not shown.

Table 6.

Comparison of sequence variants among the SARS-CoV genomes of SARS-CoV Taiwan area

| Samples | Location (nt) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3,852 | 11,493 | 26,477 | 26,203 | 27,812 | |

| TC1 | C | T | G | C | C |

| TC2 | C | T | G | T | T |

| TC3 | C | T | G | T | T |

| TWC3 | C | T | G | C | C |

| TWY | C | T | G | T | T |

| TWS | C | T | G | T | T |

| TWK | C | T | G | T | T |

| TWJ | C | T | G | T | T |

| TWC | T | C | T | C | C |

| TWC2 | C | T | G | C | C |

| TW1 | T | C | T | C | C |

| TWH | C | T | G | C | C |

| Others* | T | C | T+ | C | C |

The SARS-CoV from other area.

Except AY282752 (26,477G).

The phylogenetic analysis is shown in figure 4. We analyzed the cases associated with the Hotel M of Hong Kong and the cases in Taiwan. Two major clusters were observed after the cases were analyzed.

Fig. 4.

Molecular relationships between 20 SARS-CoV genomes which linked to infection acquired at the Hotel M in Hong Kong are shown. Phylogenetic trees were obtained by applying ClustalW to complete genome sequences of all 20 SARS-CoV published in GenBank.

Discussion

We developed a rapid method to sequence and analyze the whole genome of SARS-CoV from clinical specimens. It has been reported that some pathogenic microbes undergo adaptation in response to laboratory culturation. Host-mediated mutations in several viruses have been documented, such as HIV, Japanese encephalitis, hepatitis A, Sendai and influenza A viruses [17, 18, 19, 20]. Molecular evolution studies using such sequences may be at risk of the data containing laboratory factors [16]; the analytic data that do not represent random samples of natural pathogen populations or the sampling design is unknown. In this study, we can directly detect the whole genome of SARS-CoV from clinical samples, so that it will avoid the bias mentioned above. Although TC1 (a clinical specimen) and TWC (an isolate) were from the same patient, phylogenetic analysis revealed that they were located at different positions of the phylogenetic tree. Our results confirmed that the sequences of a cultural isolate may be different from those of a clinical specimen although they are derived from the same origin. We analyzed the sequences of the variant observed in cultural isolates and clinical specimens which were published in GenBank. Interestingly, we found that the nt 3,852 C, 11,493 T and 26,477 G appeared in all the clinical specimens, but only in two of 23 cultural isolates. The nt 3,852 T, 11,493 C and 26,477 T were found in all the cultural isolates except TWC2 and in none of clinical specimens (table 5). From these discrepancies, these mutations may be most likely due to cultural adaptation, but we are unable to completely exclude the possibility of the shifting of two original different viruses during culturing process.

In clinical specimens or cultural isolates, two variants segregated tightly, nt 26,203 C with 27,812 C (C:C) and 26,203 T with 27,812 T (T:T). The C:C type appeared in TC1 and TWC3, and all the isolates in other infection areas of the world. The T:T type appeared only in the Taiwan area. From these results, the SARS infection in Taiwan could be from two origins. One is from either the Amoy Garden or Hotel M in Hong Kong, the other has yet to be identified.

There were 4 sequence variations (nt 8,160, 13,098, 26,203, 27,812) in clinical specimens. All of the variations did not change the amino acid coding, indicating that the SARS-CoV maintains a stable structure, and it may favor the development of SARS-CoV vaccine. In the cultural isolates, we found 2 missense mutations that were all located at the M protein coding region. These mutations may be necessary for cultural adaptation. They may also appear in the clinical specimens, caused by other factors such as immunological adaptation. The M protein of SARS-CoV may play an important role in the immune response of infected patients.

Multiplex RT-PCR methods have been used to study the expression of more than ten genes simultaneously [21], to detect pathogens or subtypes [22, 23], and to verify multiple chromosome translocations [24]. In order to increase the specificity, a nested PCR [22] or a probe [25], enzyme hybridization methods [26], or microarray [27] have been used. In this study, we used multiplex RT-PCR to amplify the whole SARS genome in two separate reactions, and the PCR products were further amplified using 15 pairs of nested primers so that the products covered the whole genome in 15 separate tubes. The 15 PCR products were then sequenced. A similar approach has been used to analyze the HN gene of human parainfluenza virus [28], however, only a small portion of human parainfluenza genomes was analyzed. In contrast to this report, we analyze the whole genome of the biggest RNA virus. Although multiple RT-PCR to amplify the whole SARS genome can be used as a detection method, it is difficult to evaluate the quantitative change in the clinical specimens. So, we first amplified the Pol region of SARS virus to detect the virus and evaluate the quantitative changes of SARS virus, and then used multiplex RT-PCR and direct sequencing to analyze the whole genome.

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Shih-Feng Tsai for helpful discussions on the SARS-CoV sequences. This work was supported by a grant from China Medical University and by special SARS grant from the National Science Council, Taiwan (NSC92-2751-B039-002-Y, NSC92-2751-B-039-007-Y).

References

- 1. WHO: Summary table of SARS cases by country, November 1, 2002, August 7 2003. http://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/2003-07-11/en/

- 2.Reilley B, Van Herp M, Sermand D, Dentico N. SARS and Carlo Urbani. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1951–1952. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp030080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peiris JS, Lai ST, Poon LL, Guan Y, Yam LY, Lim W, Nicholls J, Yee WK, Yan WW, Cheung MT, Cheng VC, Chan KH, Tsang DN, Yung RW, Ng TK, Yuen KY. SARS study group: Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee N, Hui D, Wu A, Chan P, Cameron P, Joynt GM, Ahuja A, Yung MY, Leung CB, To KF, Lui SF, Szeto CC, Chung S, Sung JJ. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1986–1994. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsang KW, Ho PL, Ooi GC, Yee WK, Wang T, Chan-Yeung M, Lam WK, Seto WH, Yam LY, Cheung TM, Wong PC, Lam B, Ip MS, Chan J, Yuen KY, Lai KN. A cluster of cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1977–1985. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poutanen SM, Low DE, Henry B, Finkelstein S, Rose D, Green K, Tellier R, Draker R, Adachi D, Ayers M, Chan AK, Skowronski DM, Salit I, Simor AE, Slutsky AS, Doyle PW, Krajden M, Petric M, Brunham RC, McGeer AJ. National Microbiology Laboratory, Canada; Canadian Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Study Team: Identification of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Canada. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1995–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ksiazek TG, Erdman D, Goldsmith CS, Zaki SR, Peret T, Emery S, Tong S, Urbani C, Comer JA, Lim W, Rollin PE, Dowell SF, Ling AE, Humphrey CD, Shieh WJ, Guarner J, Paddock CD, Rota P, Fields B, DeRisi J, Yang JY, Cox N, Hughes JM, LeDuc JW, Bellini WJ, Anderson LJ. SARS Working Group: A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1953–1966. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drosten C, Gunther S, Preiser W, van der Werf S, Brodt HR, Becker S, Rabenau H, Panning M, Kolesnikova L, Fouchier RA, Berger A, Burguiere AM, Cinatl J, Eickmann M, Escriou N, Grywna K, Kramme S, Manuguerra JC, Muller S, Rickerts V, Sturmer M, Vieth S, Klenk HD, Osterhaus AD, Schmitz H, Doerr HW. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1967–1976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rota PA, Oberste MS, Monroe SS, Nix WA, Campagnoli R, Icenogle JP, Penaranda S, Bankamp B, Maher K, Chen MH, Tong S, Tamin A, Lowe L, Frace M, DeRisi JL, Chen Q, Wang D, Erdman DD, Peret TC, Burns C, Ksiazek TG, Rollin PE, Sanchez A, Liffick S, Holloway B, Limor J, McCaustland K, Olsen-Rasmussen M, Fouchier R, Gunther S, Osterhaus AD, Drosten C, Pallansch MA, Anderson LJ, Bellini WJ. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. 2003;300:1394–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.1085952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marra MA, Jones SJ, Astell CR, Holt RA, Brooks-Wilson A, Butterfield YS, Khattra J, Asano JK, Barber SA, Chan SY, Cloutier A, Coughlin SM, Freeman D, Girn N, Griffith OL, Leach SR, Mayo M, McDonald H, Montgomery SB, Pandoh PK, Petrescu AS, Robertson AG, Schein JE, Siddiqui A, Smailus DE, Stott JM, Yang GS, Plummer F, Andonov A, Artsob H, Bastien N, Bernard K, Booth TF, Bowness D, Czub M, Drebot M, Fernando L, Flick R, Garbutt M, Gray M, Grolla A, Jones S, Feldmann H, Meyers A, Kabani A, Li Y, Normand S, Stroher U, Tipples GA, Tyler S, Vogrig R, Ward D, Watson B, Brunham RC, Krajden M, Petric M, Skowronski DM, Upton C, Roper RL. The genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Science. 2003;300:1399–1404. doi: 10.1126/science.1085953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruan YJ, Wei CL, Ee AL, Vega VB, Thoreau H, Su ST, Chia JM, Ng P, Chiu KP, Lim L, Zhang T, Peng CK, Lin EO, Lee NM, Yee SL, Ng LF, Chee RE, Stanton LW, Long PM, Liu ET. Comparative full-length genome sequence analysis of 14 SARS coronavirus isolates and common mutations associated with putative origins of infection. Lancet. 2003;361:1779–1785. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13414-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization Multicentre Collaborative Network for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) Diagnosis A multicentre collaboration to investigate the cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1730–1733. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13376-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horzinek MC. Molecular evolution of corona- and toroviruses. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;473:61–72. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4143-1_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai MM, Cavanagh D. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv Virus Res. 1997;48:1–100. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60286-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Domingo E, Escarmis C, Sevilla N, Moya A, Elena SF, Quer J, Novella IS, Holland JJ. Basic concepts in RNA virus evolution. FASEB J. 1996;10:859–864. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.8.8666162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bush RM, Smith CB, Cox NJ, Fitch WM. Effects of passage history and sampling bias on phylogenetic reconstruction of human influenza A evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6974–6980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.6974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graff J, Normann A, Feinstone SM, Flehmig B. Nucleotide sequence of wild type hepatitis A virus GBM in comparison with two cell culture-adapted variants. J Virol. 1994;68:548–554. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.548-554.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Itoh M, Isegawa Y, Hotta H, Homma M. Isolation of an avirulent mutant of Sendai virus with two amino acid mutation from a highly virulent field strain through adaptation to LLC-MK2 cells. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:3207–3215. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-12-3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sawyer LS, Wrin MT, Crawford-Miksza L, Potts B, Wu Y, Weber PA, Alfonso RD, Hanson CV. Neutralization sensitivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is determined in part by the cell in which the virus is propagated. J Virol. 1994;68:1342–1349. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1342-1349.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ni H, Chang GJ, Xie H, Trent DW, Barrett AD. Molecular basis of attenuation of neurovirulence of wild-type Japanese encephalitis virus strain SA14. J Gen Virol. 1995;76:409–413. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-2-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamamoto M, Yamamoto F, Luong TT, Williams T, Kominato Y, Yamamoto F. Expression profiling of 68 glycosyltransferase genes in 27 different human tissues by the systematic multiplex reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction method revealed clustering of sexually related tissues in hierarchical clustering algorithm analysis. Electrophoresis. 2003;24:2295–2307. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coiras MT, Perez-Brena P, Garcia ML, Casas I. Simultaneous detection of influenza A, B, and C viruses, respiratory syncytial virus, and adenoviruses in clinical samples by multiplex reverse transcription nested-PCR assay. J Med Virol. 2003;69:132–144. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Podder SK, Espina R, Schnurr DP. Evaluation of a single-step multiplex RT-PCR for influenza virus type and subtype detection in respiratory samples. J Clin Lab Anal. 2003;16:163–166. doi: 10.1002/jcla.10036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi RZ, Morrissey JM, Rowley JD. Screening and quantification of multiple chromosome translocations in human leukemia. Clin Chem. 2003;49:1066–1073. doi: 10.1373/49.7.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peter M, Gilbert E, Delattre O. A multiplex real-time PCR assay for the detection of gene fusions observed in solid tumors. Lab Invest. 2001;81:905–912. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liolios L, Jenney A, Spelman D, Kotsimbos T, Catton M, Wesselingh S. Comparison of a multiplex reverse transcription-PCR-enzyme hybridization assay with conventional viral culture and immunofluorescence techniques for the detection of seven viral respiratory pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:2779–2783. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.8.2779-2783.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, Chen S, Evans DH. Typing and subtyping influenza virus using DNA microarrays and multiplex reverse transcriptase PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:696–704. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.2.696-704.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Echevarria JE, Erdman DD, Meissner HC, Anderson L. Rapid molecular epidemiologic studies of human parainfluenza viruses based on direct sequencing of amplified DNA from a multiplex RT-PCR assay. J Virol Methods. 2000;88:105–109. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(00)00163-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]