Abstract

Objective:

To describe the authors’ experience and comparative results after introducing noncardiac fellowship-trained anesthesiologists to a service previously managed by fellowship-trained cardiac anesthesiologists caring for left ventricular assist device (LVAD) patients undergoing low-risk noncardiac procedures with anesthesia.

Design:

A retrospective chart review.

Setting:

Single-site academic medical center in the United States.

Interventions:

Anesthesia and intraoperative therapy.

Measurements and Main Results:

After initiating a brief training period for the noncardiac fellowship-trained anesthesiologists and blending the noncardiac anesthesiologists into the care of LVAD patients, the electronic medical records of 158 patients with an LVAD who underwent noncardiac procedures were reviewed. The cases were managed by either cardiac-trained anesthesiologists or noncardiac-trained anesthesiologists. Their performance was evaluated on the basis of technique and outcome. The parameters for technique were the use of intubation and mechanical ventilation, use of vasoactive medications, type of vasoactive medications administered, use of invasive monitoring, and type and amount of intravenous fluid administration. The outcomes examined included occurrence of intraoperative mean blood pressure < 55 mmHg, intraoperative cardiac arrest, intraoperative device malfunction, thromboembolic complications, inability to complete procedure due to intraoperative nonsurgical complication, unplanned postoperative intensive care unit admission, unplanned hospital readmission within 30 days, and the 30-day postoperative mortality rate. This analysis demonstrated no statistically significant associations between the type of anesthesiologist and the use of fluid, amount of fluid given, use of vasopressors, or use of invasive monitoring devices. There were no significant differences in specific patient outcomes by anesthesia provider type.

Conclusions:

Patients with LVADs can be managed by either a noncardiac or a cardiac fellowship-trained anesthesiologist with similar technique and outcome during low-risk noncardiac procedures and surgeries.

Keywords: left ventricular assist device, noncardiac anesthesiologist, cardiac anesthesiologist, general anesthesiologist, noncardiac surgery, management, outcomes

LEFT VENTRICULAR ASSIST DEVICES (LVADs) are becoming more widespread.1 Patients with these devices are living longer and need more coincident medical procedures and surgeries. Gastrointestinal procedures such as endoscopy are very common.2 Because of the increased appearance of LVAD-dependent patients for noncardiac surgery, debate has arisen over what type of anesthesia training is required to adequately care for these patients.3,4 Currently the literature concerning this topic is incomplete. Several studies have examined this question,5,6 but these studies had a limited number of patients and a wide variety of LVAD training exposure. It is important to study the noncardiac anesthesiologist’s performance in managing patients with these devices because there are limited numbers of fellowship-trained cardiac anesthesiologists. The goal of this retrospective study was to describe the authors’ experience in a moderate-volume LVAD center with blending noncardiac-trained anesthesiologists into the care of LVAD patients during noncardiac procedures after limited additional training and to describe any differences in efficacy, outcome, or anesthetic technique.

Methods

Until January 2015, anesthesia support in the authors’ institution for noncardiac procedures and surgeries for patients with LVADs was provided by a fellowship-trained cardiac anesthesiologist; thereafter, some noncardiac fellowship-trained anesthesiologists have provided anesthesia care for approximately half of these procedures. Training for the noncardiac anesthesiologists consisted of 2 hours of video training designed to familiarize the anesthesiologists with the technical aspects of the devices, 1 hour of live lecture on LVAD management, and a very brief “shadowing period” with the pre-existing team of cardiac-trained anesthesiologists. Lecture training covered the basic components of LVADs, the interpretation of LVAD monitors, the preoperative assessment of LVAD patients, the intraoperative concerns and treatments, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, cardioversion, and defibrillation of patients with LVADS. Although the shadowing periods varied based on the comfort level of the noncardiac providers, typical shadowing periods consisted of 1 to 4 cases totaling less than 6 hours of shared management with cardiac-trained anesthesiologists.

The groups that were compared were the cardiac team, of which all team members were cardiac fellowship-trained, and the noncardiac fellowship-trained group. The cardiac fellowship-trained group’s most senior member had approximately 10 years of clinical practice after fellowship and the newest member had approximately 3 years of postfellowship experience. On the noncardiac team, there was a wide variety of clinical interest, experience, and training. Approximately one third of the team had fellowship training in intensive care unit (ICU) care but mostly in noncardiac units. Only 1 of the noncardiac team members had extensive cardiac ICU management with LVADs but little or no intraoperative management experience. None of the other ICU-trained anesthesiologists had any significant ICU experience with LVADs and essentially no intraoperative management of LVADs. The remaining two thirds of the noncardiac team had essentially no experience with intraoperative or nonoperative management of LVADs. Some of the younger members of this group had limited LVAD exposure in residency, but essentially none of them had any experience with intraoperative management of LVADs during noncardiac surgery. All the noncardiac anesthesiologists, however, had extensive experience with taking care of very high-risk patients for noncardiac surgery, including patients with heart failure. The years of clinical experience among the noncardiac team were a continuum from as little as 1 year of clinical experience to more than 40 years of experience in clinical practice.

After institutional review board approval, the authors conducted a retrospective, single-site electronic chart review of 158 LVAD patients who underwent noncardiac procedures from January 1, 2015, to June 15, 2016, at the Medical University of South Carolina. All patients were older than 18 years and had a HeartMate II (Thoratec Corporation, Pleasanton, CA) LVAD placed before the noncardiac procedure was investigated. All these patients had an American Society of Anesthiologists (ASA) physical status classification of 3 or 4. Patients were a mix of inpatients and outpatients. The patients all received care at the Ashley River Tower building of the Medical University of South Carolina. At the time of the study, approximately 15 LVADs were inserted per year and approximately 100 LVAD patients per year needed a noncardiac procedure or surgery requiring anesthesia services. The preoperative evaluations for each patient were completed by the anesthesiologist assigned to the case. An LVAD technician or LVAD nurse always was available for all patients but typically not present in the operating room/procedure area during the case.

The data collected fell into the following 2 main categories: (1) intraoperative anesthetic techniques and (2) patient outcomes. Specific anesthetic variables examined included the use of intubation and mechanical ventilation, use of vasoactive medications, type of vasoactive medications administered, use of invasive monitoring, and type and amount of intravenous fluid administration. Specific patient outcomes examined included the occurrence of intraoperative mean blood pressure o55 mmHg, intraoperative cardiac arrest, intraoperative device malfunction, thromboembolic complications, inability to complete the procedure due to intraoperative nonsurgical complication, unplanned postoperative ICU admission, unplanned hospital readmission within 30 days, and 30-day postoperative mortality rate. Because this was a retrospective review, there was no formal randomization of cases; however, the schedules for these cases were assigned the night before with generally no information of the specific severity of patient illness or the presence of an LVAD. The only thing that was revealed at the time of schedule posting was the type of the case (eg, Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS), Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatograhy (ERCP), endoscopy). Within these parameters, the noncardiac and cardiac anesthesiologists were assigned randomly to a case.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were estimated for all variables in the data. Associations between types of anesthesia provider and categorical variables were evaluated using the chi-square or Fisher exact test, as appropriate. Associations between type of anesthesia provider and continuous variables were evaluated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC).

A post-hoc power analysis was conducted to determine what effect sizes were powered to be detected. For categorical outcomes, the sample size of 158 total subjects (78 general and 80 cardiac anesthesiologists) provided 80% power to detect a difference in the proportion of patients with the outcome in the 2 provider groups, ranging between 17% and 23% based on a 2-sided Fisher exact test and significance level of 0.05.

Results

Of the 158 study patients enrolled, approximately 78 (49.4%) were managed by a noncardiac anesthesiologist and 80 (50.6%) were managed by a fellowship-trained cardiac anesthesiologists. All patients were classified as ASA 3 or 4 in clinical risk status. Essentially none of the cases was a true emergency or a recent LVAD implantation, but a few were urgent for infection or controlled bleeding. Most of the cases were elective and typically took place during the regular weekday schedule. None of the cases took place without a cardiac anesthesiologist at the hospital. The choice of monitored anesthesia care or general anesthesia was determined by the anesthesiologist assigned to the case and the choice of total intravenous anesthesia versus inhalational technique was also determined by the assigned anesthesiologist. No patient underwent a procedure with only a regional anesthetic. All patients were monitored using ASA standard monitors including electrocardiography, pulse oximetry, noninvasive blood pressure, and end-tidal carbon dioxide. The addition of invasive monitors such as arterial pressure monitoring or central pressure monitoring was determined by the individual anesthesiologist assigned to the case and is reflected in Table 1. The patients typically were placed in the supine or left lateral decubitus position for cases lasting less than 2 hours.

Table 1.

Procedural Characteristics and Patient Outcomes Across All Anesthesiologists and by Anesthesiologist Type

| Outcome | All (n = 158) | General (n = 78) | Cardiac (n = 80) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural differences | ||||

| Use intubation (yes) | 67 (42.4) | 28 (35.9) | 39 (48.8) | 0.102 |

| Use postoperative mechanical ventilation (yes) | 2 (1.27) | 1 (1.28) | 1 (1.25) | 1.000 |

| Use vasoactive drugs (yes) | 119 (75.3) | 61 (78.2) | 58 (72.5) | 0.406 |

| Type of vasoactive drug | 0.695 | |||

| Epinephrine | 41 (34.5) | 20 (32.8) | 21 (36.2) | |

| Phenylephrine | 78 (65.5) | 41 (67.2) | 37 (63.8) | |

| Use invasive monitoring (yes) | 37 (23.6) | 17 (22.1) | 20 (25.0) | 0.666 |

| Any fluid given (yes) | 106 (67.1) | 51 (65.4) | 56 (70.0) | 0.430 |

| Volume of crystalloid (mL) | 300 (300) | 350 (250) | 300 (375) | 0.108 |

| Patient outcomes | ||||

| Any complications (yes) | 92 (58.2) | 45 (57.7) | 47 (58.8) | 0.893 |

| Any complication other than MBP < 55 (yes) | 8 (5.06) | 3 (3.85) | 5 (6.25) | 0.720 |

| Specific complications | ||||

| MBP < 55 (yes) | 90 (56.96) | 43 (55.1) | 47 (58.8) | 0.646 |

| Intraoperative cardiac arrest (yes) | 1 (0.63) | 1 (1.28) | 0 (0.00) | 0.494 |

| Intraoperative device malfunction (yes) | 1 (0.63) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.25) | 1.000 |

| Thromboembolic event (yes) | 1 (0.63) | 1 (1.28) | 0 (0.00) | 0.494 |

| Ended procedure due to nonsurgical complications (yes) | 1 (0.63) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.25) | 1.000 |

| Unplanned ICU admission (yes) | 1 (0.63) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (1.25) | 1.000 |

| Unplanned 30-d hospital readmission (yes) | 2 (1.27) | 1 (1.28) | 1 (1.25) | 1.000 |

| 30-d mortality (yes) | 4 (2.53) | 1 (1.28) | 3 (3.75) | 0.620 |

NOTE. Categorical variables are presented as n (%) and continuous variables as median (interquartile range).

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; MBP, mean blood pressure.

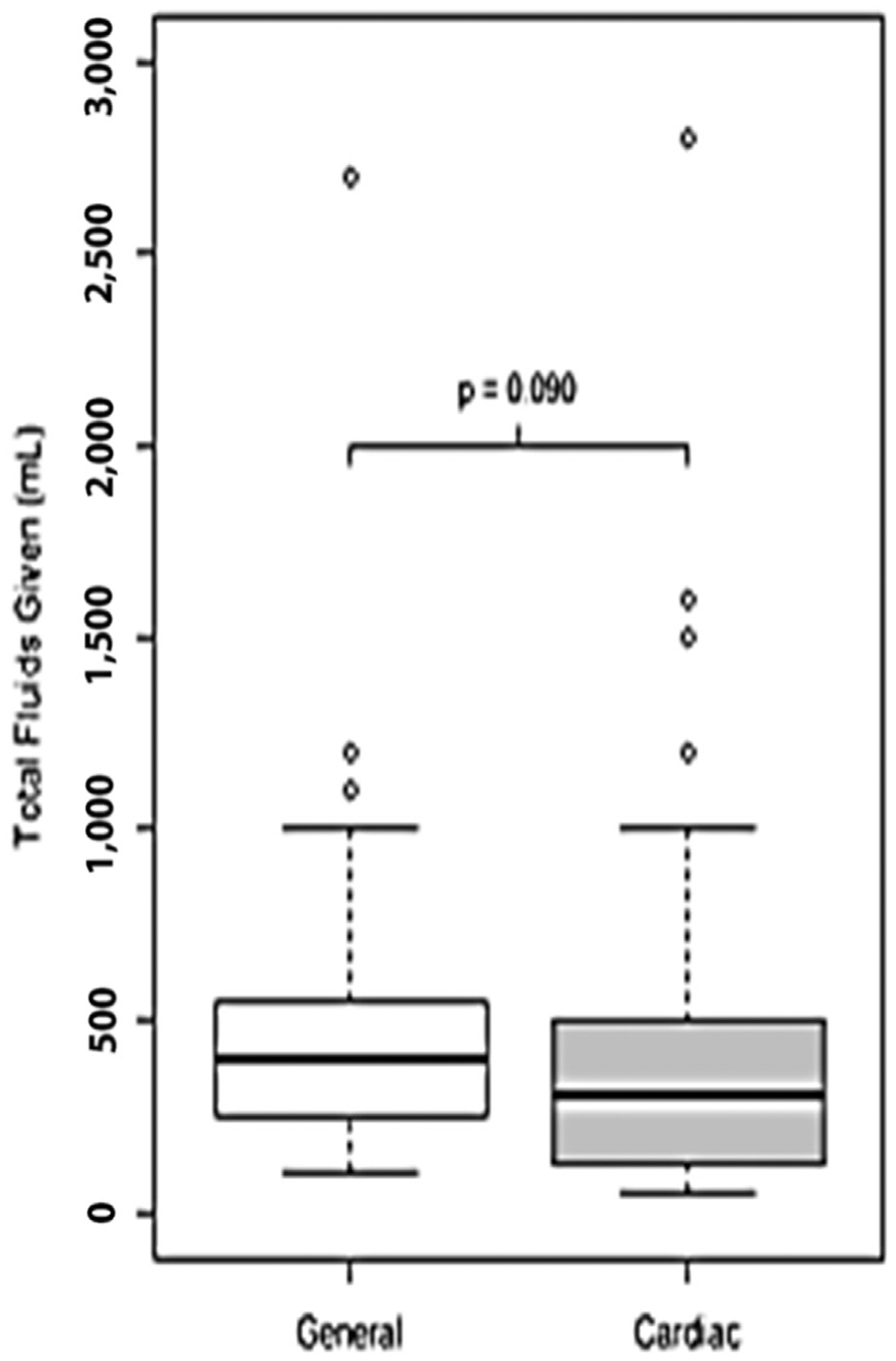

The majority of patients received vasoactive drugs (75.3%) and fluids (67.1%), with a median volume of 300 mL of fluid given. Only 1 patient received colloid (packed red blood cells), whereas the rest received a balanced crystalloid solution. There were no statistically significant associations between type of anesthesiologist and use of fluid, amount of fluid given, use of vasoactive medications, and use of invasive monitoring devices (see Table 1). A larger proportion of cardiac anesthesiologists used intubation compared with noncardiac anesthesiologists, although the difference was not statistically significant (49% v 36%, p = 0.102) (see Table 1). In addition, there was a trend toward cardiac anesthesiologists giving less total fluid, although again this did not achieve statistical significance (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Box plots of total intraoperative fluid volume given among patients for whom fluid administration was recorded.

The overall complication rate was 58%. Of cases conducted by general anesthesiologists, 57.7% had complications compared with 58.8% of cases conducted by cardiac anesthesiologists (p = 0.893). The most frequent complication was patients experiencing a mean blood pressure < 55 mmHg at some point intraoperatively. Incidence rates for all other complications were less than 5% across and within provider type. There were no significant differences in specific patient outcomes by anesthesia provider type. Comparisons between general and cardiac anesthesiologists are reported in Table 1.

Discussion

Traditionally, patients with LVAD devices have been managed by a cardiothoracic anesthesiologist, but there is some evidence that this trend may be changing.7 In the authors’ institution, approximately 100 LVAD patients are seen per year for noncardiac surgeries or procedures requiring anesthesia. Before the present study was conducted, these cases were performed by a team of cardiac fellowship-trained anesthesiologists. Most of these cases were endoscopic in nature. Because the number of LVAD cases increased, providing cardiac fellowship-trained medical direction presented a strain on personnel resources; therefore, after a short training period, noncardiac anesthesiologists also began to assume the care of these patients.

This descriptive study demonstrated no substantial difference in the quality or technique of care delivered to these patients. There were no statistically significant associations between type of anesthesiologist and the use of fluid, amount of fluid given, use of vasopressors, and use of invasive monitoring devices. General anesthesiologists tended to have fewer intubated patients and slightly fewer cases with hypotension, but these trends were not statistically significant. General anesthesiologists had a trend toward giving more fluid and more vasoactive drugs, but neither of these trends reached statistical significance. Outcome data did not show any statistical difference between the 2 groups. Because this study was not randomized, there is a possibility that the cardiac-trained anesthesiologists may have taken care of a slightly higher proportion of less stable LVAD patients, thereby biasing the results. Because of the relatively rare incidence of adverse outcome events in either group, the power of this experience also is limited. The one outcome parameter that did occur with some regularity was hypotension. This, however, showed no statistical difference between the 2 groups. The variables examined were determined by the authors based on several preceding studies investigating similar topics. Hypotension also was included because it has been suggested that it affects morbidity and mortality.8 Comparing hypotension as a parameter was appealing because it is modifiable by the caregiver, universally available, and fairly prevalent.

This retrospective examination of the authors’ experience demonstrates that over the 18 months of chart reviews, noncardiac anesthesiologists were able to care for LVAD patients undergoing low-risk endoscopic and general surgery procedures without a noticeable change in the quality of care delivered to these patients. This information is of benefit to these patients by improving their access to care. Before the blending of noncardiac anesthesiologists into the care of these LVAD patients for noncardiac cases and procedures at the authors’ institution, treatment for LVAD patients with nonemergency cases were being postponed because of scheduling difficulties involving the lack of availability of cardiac anesthesiologists. This study in no way suggests that the additional training of the cardiac anesthesiologist is not helpful in the care of these challenging patients or that the noncardiac anesthesiologists did not significantly benefit from the co-location of the cardiac fellowship group. It does suggest that noncardiac anesthesiologists can provide adequate and safe care to LVAD patients undergoing low-risk procedures. The authors’ conclusions may not extend to facilities that do not have co-location of a cardiac fellowship-trained anesthesiologist or to facilities in which the noncardiac anesthesiologist does not have extensive experience with high-risk patients for noncardiac surgery, including patients with severe heart failure.

The information presented here is timely because anesthesiologists are moving toward this type of care model but few actually are studying it. This study was powered to detect differences in mean arterial blood pressure < 55 mmHg, and although this has not been established as sine qua non for quality of care, Walsh et al. have suggested that any amount of time of the mean blood pressure at < 55 mmHg is associated with adverse outcomes.8 That study may not be directly applicable to patients with continuous-flow LVADs, but it does examine a parameter that is universally retrievable and comparable within the limitations of a retrospective review. Even though the information presented is relevant to the current clinical climate, the authors acknowledge that the present study has many limitations, and therefore conclusions from this study should be moderated by clinical judgment and the body of literature on this subject. This study was retrospective, not formally randomized, and was underpowered for many of the outcome parameters with the exception of hypotension. These limitations are mirrored in other works on this subject.5,6,9 To be able to detect differences in the less frequent parameters, such as mortality, well over 1,000 patients would be needed. With a single institution study the time needed to encounter this volume of LVAD patients would run the risk of having too many other variables change (eg, the type of LVAD device), thereby possibly limiting comparisons.

In summary, this study adds to the growing body of literature that supports the notion that noncardiac-trained anesthesiologists are capable of providing adequate care to LVAD patients presenting for low-risk noncardiac procedures and surgeries. Unlike other previous studies, the authors included hypotension as an outcome parameter, and this parameter also supports this notion. This study suggests that care by noncardiac fellowship-trained anesthesiologists can be achieved with only a brief additional training period and only modest modification of their general knowledge of anesthesiology and intraoperative medicine. This type of additional training could be undertaken easily in any institution routinely caring for LVAD patients and hopefully will be incorporated into the experience of most anesthesia training programs in the future. More study clearly is essential in this area, but performing large randomized studies may prove difficult because of the infrequent nature of adverse outcomes and the growing but somewhat still infrequent presentation of these patients at single-center institutions.

References

- 1.Lampropulos JF, Kim N, Wang Y, et al. Trends in left ventricular assist device use and out comes among Medicare beneficiaries, 2004–2011. Open Heart 2014;1:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Islam S, Cevik C, Madonna R, et al. Left ventricular assist devices and gastrointestinal bleeding: A narrative review of case reports and case series. Clin Cardiol 2013;36:190–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhandary S Con: Cardiothoracic anesthesiologists are not necessary for the management of patients with ventricular assist devices undergoing noncardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2017;31:382–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stoicea N, Sacchet-Cardozo F, Joseph N, et al. Pro: Cardiothoracic anesthesiologists should provide anesthetic care for patients with ventricular assist devices undergoing noncardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2017;31:378–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone M, Hinchey J, Sattler C, et al. Trends in the management of patients with left ventricular assist devices presenting for noncardiac surgery: A 10-year institutional experience. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2016;20: 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goudra BG, Singh PM. Anesthesia for gastrointestinal endoscopy in patients with left ventricular assist devices: Initial experience with 68 procedures. Ann Cardiac Anaesth 2013;16:250–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheu R, Joshi B, High K, et al. Perioperative management of patients with left ventricular assist devices undergoing noncardiac procedures: A survey of current practices. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2015;29:17–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh M, Devereaux PJ, Garg AX, et al. Relationship between intraoperative mean arterial pressure and clinical outcomes after noncardiac surgery: Toward an empirical definition of hypotension. J Am Soc Anesthesiol 2013;119:507–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson EW, Heinke T, Finley A, et al. Management of LVAD patients for noncardiac surgery: A single-institution study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2015;29:898–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]