Abstract

In skeletal and cardiac muscles, contraction is triggered by an increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration. During Ca2+ transients, Ca2+-binding to troponin C shifts the “on–off” equilibrium of the thin filament state toward the “on” sate, promoting actomyosin interaction. Likewise, recent studies have revealed that the thin filament state is under the influence of temperature; viz., an increase in temperature increases active force production. In this short review, we discuss the effects of temperature on the contractile performance of mammalian striated muscle at/around body temperature, focusing especially on the temperature-dependent shift of the “on–off” equilibrium of the thin filament state.

Keywords: actomyosin, Ca2+ sensitivity, cardiac muscle, skeletal muscle, temperature, tropomyosin, troponin

Introduction

Under physiological conditions, striated muscle generates force and heat. Skeletal muscle plays a critical role in maintaining body temperature which increases during exercise. Human body temperature is maintained at ∼37 ± 1°C throughout the day (Refinetti, 2010; Geneva et al., 2019). In humans, body temperature rises to ∼39°C during exercise (Saltin et al., 1968) and exceeds ∼40°C during heat-related illnesses (e.g., heat stroke and malignant hyperthermia) (Glazer, 2005; Rosenberg et al., 2015). Physiologists have long perceived that a change in body temperature affects the mechanical properties of skeletal and cardiac muscles, such as active force generation and shortening velocity. However, the molecular mechanisms are yet to be fully understood, due, primarily, to the fact that sarcomere proteins have varying degrees of temperature sensitivity. Here, we briefly review the effects of temperature on the mechanical properties of skeletal and cardiac muscles in the range between ∼36 and ∼40°C, and discuss how striated muscle works efficiently at/around body temperature.

Excitation–Contraction Coupling

Contraction of skeletal and cardiac muscles is initiated by depolarization of the sarcolemmal membrane. In skeletal muscle, sarcolemmal depolarization directly triggers the release of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) via ryanodine receptors; however, in cardiac muscle, it is the Ca2+ entry from the extracellular fluid through voltage-dependent L-type Ca2+ channels that triggers the Ca2+ release, a mechanism known as Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (Bers, 2002; Endo, 2009). In both skeletal and cardiac muscles, an increase in the intracellular Ca2+concentration ([Ca2+]i) promotes Ca2+ binding to troponin C (TnC) on thin filaments (Fukuda et al., 2009; Kobirumaki-Shimozawa et al., 2014). Unlike in skeletal muscle, cardiac myofilaments are not fully activated under physiological conditions because [Ca2+]i is maintained relatively low (∼10–6 M), even at the peak of systole (Bers, 2002). Because of this partial activation nature, cardiac myofilaments exhibit non-linear properties, such as length-dependent activation (Kobirumaki-Shimozawa et al., 2014) and spontaneous sarcomeric auto-oscillations (SPOC) (see Ishiwata et al., 2011; Kagemoto et al., 2018). In both skeletal and cardiac muscles, lowering [Ca2+]i dissociates Ca2+ from TnC, resulting in dissociation of myosin from thin filaments, i.e., relaxation.

Ca2+-Dependent Activation of Thin Filaments

Ca2+-activated muscle contraction is mediated by regulatory proteins, i.e., troponin (Tn) and tropomyosin (Tm), which form a complex on actin filaments. At rest, the Tn–Tm complex prevents/weakens actomyosin interaction. At this “off” state, the carboxyl-terminal domain of TnI strongly binds to actin, and Tm blocks myosin binding to actin and/or force production of bound myosin. When [Ca2+]i is increased, Ca2+-bound TnC interacts with TnI, and the carboxyl-terminal domain of TnI is dissociated from actin. The Tn conformational changes result in displacement of Tm on actin, which subsequently induces myosin binding to actin and force generation (e.g., Haselgrove, 1973; Huxley, 1973; Lehman et al., 1994; Vibert et al., 1997; Xu et al., 1999; Fukuda et al., 2009; Risi et al., 2017; Matusovsky et al., 2019). It has been reported that during the shift of the thin filament state from “off” to “on,” strongly bound myosin cooperatively enhances binding of neighboring myosin molecules that have ATP and thereby potentially produce force (Greene and Eisenberg, 1980; Trybus and Taylor, 1980).

Modulation of Myofibrillar Ca2+ Sensitivity

The “on–off” equilibrium of the thin filament state is most typically reflected as Ca2+ sensitivity of active force development in skinned fibers. The parameter pCa50 (= −log[Ca2+]) (required for half-maximal Ca2+-activated force) is widely used to express Ca2+ sensitivity; an increase in the pCa50 value indicates an increase in Ca2+ sensitivity and vice versa. Ca2+ sensitivity is influenced by various factors, such as the intracellular concentrations of Mg2+ (Fabiato and Fabiato, 1975; Best et al., 1977; Donaldson et al., 1978), MgATP (Fabiato and Fabiato, 1975; Best et al., 1977), MgADP (Fukuda et al., 1998, 2000) and inorganic phosphate (Kentish, 1986; Millar and Homsher, 1990; Fukuda et al., 1998, 2001), and ionic strength (Kentish, 1984; Fink et al., 1986) and pH (Fabiato and Fabiato, 1978; Orchard and Kentish, 1990; Fukuda and Ishiwata, 1999; Fukuda et al., 2001). Ca2+ sensitivity is likewise under the influence of phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of thick or thin filament proteins. Most importantly, protein kinase A, activated upon β-adrenergic stimulation in cardiac muscle, phosphorylates TnI, resulting in a decrease in Ca2+ sensitivity via weakening of the TnI–TnC interaction (see Solaro and Rarick, 1998 for details). Likewise, other translational modifications such as glycation (Papadaki et al., 2018) and acetylation (Gupta et al., 2008) may affect Ca2+ sensitivity.

Effects of Temperature on the Mechanical Properties of Cardiac Muscle

A rapid decrease in solution temperature generates contraction in intact cardiac muscle [rapid cooling contracture (RCC): see Kurihara and Sakai, 1985; Bridge, 1986]. The mechanism of RCC can be explained as follows: upon lowering of the solution temperature, Ca2+ is released from the SR via ryanodine receptors (Protasi et al., 2004), causing contraction in a Ca2+-dependent manner. Chronic cooling also enhances contraction in intact cardiac muscle under varying experimental conditions (hypothermic inotropy) (Shattock and Bers, 1987; Puglisi et al., 1996; Mikane et al., 1999; Janssen et al., 2002; Hiranandani et al., 2006; Shutt and Howlett, 2008; Obata et al., 2018) (see Figure 1A and Table 1 for effects of alteration of temperature on striated muscle properties). For instance, Shattock and Bers (1987) reported that cooling from 37 to 25°C increases twitch force greater than approximately ∼fivefold in “intact” rabbit and rat ventricular muscle. However, cooling from 36 to 29°C decreases maximal Ca2+-activated force in “skinned” rabbit ventricular muscle, coupled presumably with depressed actomyosin ATPase activity, with no significant change in Ca2+ sensitivity (Harrison and Bers, 1989) (cooling to 22°C decreases both force production and Ca2+ sensitivity, see Table 1). We, therefore, consider that hypothermic inotropy is caused by the positive effect of cooling on [Ca2+]i minus its negative effect on myofibrils: viz., cooling increases the amplitude of the intracellular Ca2+ transients and prolongs the duration of the amplitude (i.e., longer time to peak [Ca2+]i and slower [Ca2+]i decline) (Puglisi et al., 1996; Janssen et al., 2002; Shutt and Howlett, 2008), hence, augmenting contractility in a Ca2+-dependent manner, by a magnitude greater than the decrease at the myofibrillar level.

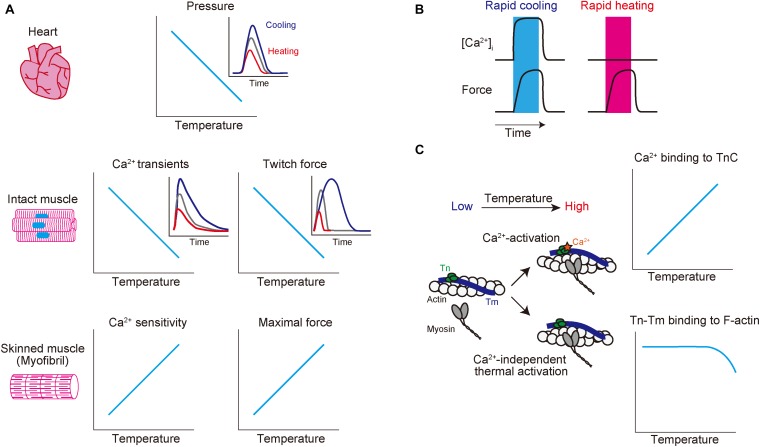

FIGURE 1.

Schematic showing the effects of altered temperature on functional properties of mammalian striated muscle. (A) Top: relationship of temperature vs. endo-systolic pressure in mammalian hearts. Inset: time-course of ventricular pressure at different temperatures. Blue, gray, and red lines indicate hypothermic, physiological, and hyperthermic conditions, respectively. Middle: relationship of temperature vs. Ca2+ transients (left) and twitch force (right) in intact muscles. Blue, gray, and red lines indicate hypothermic, physiological, and hyperthermic conditions, respectively. Bottom: relationship of temperature vs. Ca2+ sensitivity (left) and maximal force (right) in skinned muscles. (B) Effects of rapid cooling (left; shown in blue bar) or rapid heating (right; shown in red bar) on [Ca2+]i (top) and force (bottom) in intact cardiomyocytes. Rapid cooling increases both [Ca2+]i and force, while rapid heating increases force with little or no influence on [Ca2+]i. (C) Effects of a change in temperature on thin filaments. Increasing temperature 1) enhances Ca2+ binding to TnC (see top graph) and 2) induces Ca2+-independent thermal activation of thin filaments via partial dissociation of the Tn–Tm complex from actin (see bottom graph), thereby coordinately acting to increase the fraction of the “on” state of thin filaments. See text for details.

TABLE 1.

Effects of alteration of temperature on functional properties of mammalian striated muscles.

| Preparation | Parameter | Temperature change (°C) | Change in parameter value | Direction, change in parameter value | References |

| Canine heart (isolated) | Systolic pressure (mmHg) | 35.9→30.7 35.9→39.8 | 69.4→102.0* 69.4→44.8* | Increase Decrease | Mikane et al., 1999 |

| Canine heart (isolated) | Systolic pressure (mmHg) | 36.3→41 | 125.1→80.5*** | Decrease | Saeki et al., 2000 |

| Rat heart (isolated) | Systolic pressure (mmHg) | 37→32 37→42 | 103.4→134.6* 103.4→76.0* | Increase Decrease | Obata et al., 2018 |

| Guinea pig cardiac muscle | Force | 36.5→17 | – | Increase | Kurihara and Sakai, 1985 |

| Rabbit cardiac muscle | Force | 30→1 | – | Increase | Bridge, 1986 |

| Rabbit cardiac muscle | Twitch force | 37→25 | – | Increase | Shattock and Bers, 1987 |

| Rat cardiac muscle | Twitch force | 37→25 | – | Increase | Shattock and Bers, 1987 |

| Rat cardiac muscle | Twitch force (mN/mm2) | 37.5→30 | 30→86 | Increase | Janssen et al., 2002 |

| Rat cardiac muscle | Twitch force (%, normalized at 37°C) | 37→32 37→42 | – 100→67.2 | Increase Decrease | Hiranandani et al., 2006 |

| Rabbit cardiac muscle | Twitch shortening (%) | 35→25 | 7.6→13.1** | Increase | Puglisi et al., 1996 |

| Ferret cardiac muscle | Twitch shortening (%) | 35→25 | 2.9→4.9* | Increase | Puglisi et al., 1996 |

| Cat cardiac muscle | Twitch shortening (%) | 35→25 | 10.8→6.0* | Decrease | Puglisi et al., 1996 |

| Guinea pig cardiac muscle | Twitch shortening (%) | 37→22 | 2.6→8.3* | Increase | Shutt and Howlett, 2008 |

| Rabbit cardiac muscle (skinned) | Maximal force (%, normalized at 22°C) | 36→29 36→22 | 118.5→108* 118.5→100** | Decrease Decrease | Harrison and Bers, 1989 |

| Rat skeletal fiber | Resting force (intact) Resting force (skinned) | 30→40 30→40 | – – | Increase Increase | Ranatunga, 1994 |

| Rat cardiac muscle | Shortening | 36→41 | – | Increase | Oyama et al., 2012 |

| C2C12 myotube | Shortening (%) | 36.5→41.5 | 0→2.4* | Increase | Marino et al., 2017 |

| Rabbit cardiac muscle | Ca2+ transient amplitude (nM) | 35→25 | 248→454** | Increase | Puglisi et al., 1996 |

| Rat cardiac muscle | Ca2+ transient amplitude (μM) | 37.5→30 | 0.73→1.33 | Increase | Janssen et al., 2002 |

| Guinea pig cardiac muscle | Ca2+ transient amplitude (nM) | 37→22 | 35→157* | Increase | Shutt and Howlett, 2008 |

| Actin (RS) + Tm (HC) + Tn (HC) + HMM (RS) | Sliding velocity at pCa 5 Sliding velocity at pCa 9 Sliding velocity at pCa 9 | ∼20→∼60 ∼20→∼43 ∼43→∼60 | – – – | Increase No change Increase | Brunet et al., 2012 |

| Actin (RS) + Tm (HC) + Tn (BC) + HMM (RS) | Sliding velocity at pCa 5 (μm/s) Sliding velocity at pCa 9 (μm/s) | 25→41.0 25→40.8 | 6.4→17.9 0→14.5 | Increase Increase | Ishii et al., 2019 |

| Actin (RS) + Tm (HC) + Tn (BC) + HMM (BC) | Sliding velocity at pCa 5 (μm/s) Sliding velocity at pCa 9 (μm/s) | 24→40.0 24→39.9 | 1.19→8.89 0→3.37 | Increase Increase | Ishii et al., 2019 |

| Rabbit cardiac muscle (skinned) | pCa50 (active force) | 36→29 36→22 | 5.473→5.494 (NS) 5.473→5.340** | No change Decrease | Harrison and Bers, 1989 |

| Rabbit skeletal myofibril | pCa50 (ATPase) | 30→37 | 7.05→7.52 | Increase | Mühlrad and Hegyi, 1965 |

| Rabbit skeletal myofibril | pCa50 (ATPase) | 30→40 | – | Increase | Murphy and Hasselbach, 1968 |

| TnC (BC) | pCa50 (Ca2+ binding) | 21→37 | 5.29→5.42* | Increase | Gillis et al., 2000 |

| TnC (HC) | pCa50 (Ca2+ binding) | 30→45 | 5.04→5.17 | Increase | Veltri et al., 2017 |

Data obtained under various experimental conditions are summarized. Sliding velocity was obtained in the in vitro motility assay with reconstituted thin filaments (actin plus Tn–Tm). BC, bovine cardiac; HC, human cardiac; HMM, heavy meromyosin; RS, rabbit skeletal. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. NS, not significant.

In contrast, an increase in temperature to ∼40–42°C has been reported to decrease end-systolic pressure in canine (Mikane et al., 1999; Saeki et al., 2000) and rat (Obata et al., 2018) hearts. The findings of these studies were confirmed by a study using rat ventricular trabeculae where twitch force was decreased by ∼30% accompanied by an increase in temperature from 37 to 42°C (Hiranandani et al., 2006). The mechanisms of hyperthermic negative inotropy are yet to be clarified; however, a decrease in the peak or duration time of Ca2+ transients is likely to underlie the inhibited active force production.

Heating-Induced Contraction in Resting Muscle

Physiologists have realized for nearly a century that despite being under resting conditions, the warming of muscles increases active force, known as “heat contraction” or “heat rigor”. For instance, Vernon (1899) investigated heat contraction in cardiac and skeletal muscles that had been obtained from 18 species of cold-blooded animals. Likewise, Hill (1970) reported in frog sartorius muscle that resting tension is increased in a linear fashion with increasing temperature from 0 to 23°C and more steeply in the higher temperature range. Later, using intact and skinned rabbit skeletal muscle fibers, Ranatunga (1994) confirmed Hill’s finding that resting force is increased in a linear fashion in the low temperature range, i.e., <∼25°C and more sharply increased in the higher temperature range (30–40°C).

Recently, we demonstrated that rapid and repetitive heating via infrared laser irradiation (0.2 s at 2.5 Hz) induces transient and reversible shortening in isolated intact rat ventricular myocytes (Oyama et al., 2012). In this previous study, at the baseline temperature of 36°C, the magnitude of the rise in temperature to induce myocyte shortening was ∼5°C. It is important that this temperature-dependent contraction occurs in a Ca2+-independent manner, and instead, it is regulated at the sarcomere level. Indeed, intracellular Ca2+ imaging with fluo-4 revealed little or no increase in [Ca2+]i upon infrared laser irradiation, and heating-induced contraction was blocked by the myosin II inhibitor blebbistatin. A similar phenomenon was observed in C2C12 myotubes (from mouse) when temperature was increased from 36.5 to 41.5°C using gold nanoshells in combination with near-infrared laser irradiation (Marino et al., 2017). These studies using differing preparations indicate that a rise in temperature from physiological ∼37 to ∼40°C directly activates sarcomeres in a Ca2+-independent fashion (Figures 1B,C).

Thermal Activation of Thin Filaments

The characteristics of heating-induced contraction are consistent with the notion that Ca2+ sensitivity is increased with increasing temperature above 37°C (e.g., Ranatunga, 1994; Oyama et al., 2012). Mühlrad and Hegyi (1965) reported that increasing temperature in the range of 0–37°C reduces [Ca2+] for half-maximal and maximal ATPase activity in rabbit skeletal myofibrils. Warming to ∼40°C further reduces [Ca2+] for half-maximal ATPase activity in rabbit skeletal myofibrils (i.e., increased Ca2+ sensitivity) (see Murphy and Hasselbach, 1968), and interestingly, the Ca2+ sensitivity is lost at ∼50°C (Hartshorne et al., 1972).

By taking advantage of the in vitro motility assay, recent studies confirmed heating-induced activation of thin filaments by measuring the sliding velocity of reconstituted thin filaments. Brunet et al. (2012) analyzed sliding movements of thin filaments that had been reconstituted with human cTn and Tm at temperatures above ∼43°C under relaxing conditions in the absence of Ca2+ (+EGTA). We performed a rapid-heating experiment using infrared laser irradiation and found that thin filaments that had been reconstituted with bovine cTn and human Tm exhibited sliding movements at >∼35°C in the absence of Ca2+ (Ishii et al., 2019). Because the sliding velocity was ∼30% at 37°C compared to the maximum, this previous finding suggests that thin filaments are partially activated in diastole at physiological body temperature, enabling rapid and efficient myocardial dynamics in systole (see Ishii et al., 2019 for details).

The molecular mechanisms of thermal activation of thin filaments are yet to be fully understood. One possible mechanism is “partial dissociation” of Tn–Tm from F-actin upon increasing temperature (as discussed in Oyama et al., 2012; Ishii et al., 2019); viz., Tanaka and Oosawa (1971) demonstrated that Tm dissociates from F-actin at >∼40°C. Later experiments by Ishiwata (1978) on reconstituted thin filaments (F-actin plus Tn–Tm) showed that Tn–Tm starts to partially dissociate from F-actin at ∼41°C, with dissociation temperatures of 48.8 and 47.0°C in the absence and presence of Ca2+, respectively.

While in older studies the structural changes in thin filaments were unable to be detected, newer studies suggest that heating-induced Ca2+-independent contraction may result not only from partial dissociation of Tm or Tn–Tm from F-actin but also from structural changes in Tn, Tm, or both. Consistent with this view, Kremneva et al. (2003) reported that thermal unfolding occurs in Tm in reconstituted thin filaments comprised of F-actin and Tn–Tm. They found that a low-temperature transition reflecting the denaturation of the C-terminus of Tm started to occur at ∼40°C in the presence of 1 mM EGTA (hence under the relaxing condition). Likewise, it has previously been reported that instability of the coiled-coil structure of Tm is essential for optimal interaction with actin (Singh and Hitchcock-DeGregori, 2009). It is therefore likely that the unfolding of Tm may promote the shift of the thin filament state from the “off” state to the “on” state and thereby gives rise to, at least in part, heating-induced contraction.

It is likewise known that the Ca2+-binding affinity of TnC is increased with temperature. For instance, Gillis et al. (2000) reported that the Ca2+-binding affinity of bovine cardiac TnC is increased with temperature within the range between 7 and 37°C. The affinity of human cardiac TnC for Ca2+ also increases with temperature within the range between 21 and 45°C (Veltri et al., 2017). It should be noted that the temperature sensitivity of TnC for Ca2+ is isoform dependent. For instance, Harrison and Bers (1990) reported that the cooling-induced decrease in Ca2+ sensitivity is attenuated after reconstitution with skeletal TnC in skinned rat ventricular muscle.

Possible Use of Local Heating for the Treatment of Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Accumulating evidence shows that mutations in sarcomere proteins, including Tn subunits (TnT, TnI, and TnC) and Tm, modulate Ca2+ sensitivity and thereby promote the pathogenesis of DCM or HCM (Ohtsuki and Morimoto, 2008). A general consensus has been achieved in that myofibril Ca2+ sensitivity is decreased by DCM mutations and increased by HCM mutations (Ohtsuki and Morimoto, 2008; Kobirumaki-Shimozawa et al., 2014). Because an increase in temperature enables sarcomeric contraction in a Ca2+-independent manner (Oyama et al., 2012), local heating, such as via infrared laser irradiation, may have a potential to augment contractility in patients with DCM without causing the intracellular Ca2+overload that can cause fatal arrhythmias. In order to avoid hyperthermal negative inotropy, local heating targeting myofibrils, but not global heating, is essential to augment contractility of myocardium in the heart. For instance, Marino et al. (2017) demonstrated gold nanoshell-mediated remote activation of myotubes via near-infrared laser irradiation, which does not cause a change in [Ca2+]i. Likewise, heating of nanoparticles by the magnetic field may be useful to increase temperature of the myocardium in various layers from the epicardium to the endocardium of the heart in vivo (as demonstrated by Chen et al., 2015 for deep brain stimulation).

It is worthwhile noting that in previous studies discussed, thus far, different mammals were used that have different body temperatures (cf. Table 1), thus, future studies using human samples need to be conducted under various experimental conditions to systematically investigate how alteration of temperature affects the function of the heart in humans.

Conclusion

In striated muscle, sarcolemmal depolarization causes an increase in [Ca2+]i. The Ca2+-dependent structural changes of thin filaments allow for myosin binding to actin and thereby facilitate active force production. Cooling increases the contractility of striated muscle via Ca2+-dependent activation: first, a rapid decrease in temperature triggers a release of Ca2+ from the SR, and second, long-term cooling increases the amplitude as well as the period of intracellular Ca2+ transients. Contrary to these cooling effects, heating increases myofibrillar active force (and ATPase activity) and Ca2+ sensitivity; the latter is coupled with an increase in the affinity of TnC for Ca2+. Moreover, heating induces structural changes of thin filaments (i.e., partial dissociation of the Tn–Tm complex from F-actin), thereby shifting the “on–off” equilibrium of the thin filament state toward the “on” state at a given [Ca2+]i (Ca2+-independent activation). The characteristics of heating-induced, Ca2+-independent activation may be useful to augment the heart’s contractility in patients with DCM in future clinical settings.

Author Contributions

SIs, KO, and NF wrote the first version of the manuscript. SS, FK-S, and S’Is contributed comments and suggestions. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular Ca2+ concentration

- RCC

rapid cooling contracture

- SPOC

spontaneous sarcomeric auto-oscillations

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- Tm

tropomyosin

- Tn

troponin.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by PRESTO, Japan Science and Technology Agency (to KO: JPMJPR17P3), Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (to FK-S: JP18K06878), Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (to SS: 17K15102), Quantum Leap Flagship Program (Q-LEAP; to SIs: JPMXS 0118067395), the Naito Foundation (to FK-S), and Japan Heart Foundation Dr. Hiroshi Irisawa and Dr. Aya Irisawa Memorial Research Grant (to FK-S).

References

- Bers D. M. (2002). Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature 415 198–205. 10.1038/415198a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best P. M., Donaldson S. K., Kerrick W. G. L. (1977). Tension in mechanically disrupted mammalian cardiac cells: effects of magnesium adenosine triphosphate. J. Physiol. 256 1–17. 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp011702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge J. H. B. (1986). Relationships between the sarcoplasmic reticulum and sarcolemmal calcium transport revealed by rapidly cooling rabbit ventricular muscle. J. Gen. Physiol. 88 437–473. 10.1085/jgp.88.4.437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet N. M., Mihajloviæ G., Aledealat K., Wang F., Xiong P., von Molnár S., et al. (2012). Micromechanical thermal assays of Ca2 +-regulated thin-filament function and modulation by hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutants of human cardiac troponin. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012:657523. 10.1155/2012/657523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Romero G., Christiansen M. G., Mohr A., Anikeeva P. (2015). Wireless magnetothermal deep brain stimulation. Science 347 1477–1480. 10.1126/science.1261821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson S. K., Best P. M., Kerrick G. L. (1978). Characterization of the effects of Mg2 + on Ca2 +- and Sr2 +-activated tension generation of skinned rat cardiac fibers. J. Gen. Physiol. 71 645–655. 10.1085/jgp.71.6.645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo M. (2009). Calcium-induced calcium release in skeletal muscle. Physiol. Rev. 89 1153–1176. 10.1152/physrev.00040.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A., Fabiato F. (1975). Contractions induced by a calcium-triggered release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum of single skinned cardiac cells. J. Physiol. 249 469–495. 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabiato A., Fabiato F. (1978). Effects of pH on the myofilaments and the sarcoplasmic reticulum of skinned cells from cardiace and skeletal muscles. J. Physiol. 276 233–255. 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink R. H. A., Stephenson D. G., Williams D. A. (1986). Potassium and ionic strength effects on the isometric force of skinned twitch muscle fibres of the rat and toad. J. Physiol. 370 317–337. 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp015937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda N., Fujita H., Fujita T., Ishiwata S. (1998). Regulatory roles of MgADP and calcium in tension development of skinned cardiac muscle.J. Muscle Res. Cell.Motil. 19 909–921. 10.1023/a:1005437517287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda N., Ishiwata S. (1999). Effects of pH on spontaneous tension oscillation in skinned bovine cardiac muscle. Pflügers Arch. 438 125–132. 10.1007/s004240050889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda N., Kajiwara H., Ishiwata S., Kurihara S. (2000). Effects of MgADP on length dependence of tension generation in skinned rat cardiac muscle. Circ. Res. 86 E1–E6. 10.1161/01.res.86.1.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda N., O-Uchi J., Sasaki D., Kajiwara H., Ishiwata S., Kurihara S. (2001). Acidosis or inorganic phosphate enhances the length dependence of tension in rat skinned cardiac muscle. J. Physiol. 536 153–160. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00153.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda N., Terui T., Ohtsuki I., Ishiwata S., Kurihara S. (2009). Titin and troponin: central players in the frank-starling mechanism of the heart. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 5 119–124. 10.2174/157340309788166714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geneva I. I., Cuzzo B., Fazili T., Javaid W. (2019). Normal body temperature: A systematic review. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 6 1–7. 10.1093/ofid/ofz032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis T. E., Marshall C. R., Xue X. H., Borgford T. J., Tibbits G. F. (2000). Ca2 + binding to cardiac troponin C: effects of temperature and pH on mammalian and salmonid isoforms. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 279 R1707–R1715. 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.5.R1707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazer J. L. (2005). Management of heatstroke and heat exhaustion. Am. Fam. Physician 71 2133–2142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene L. E., Eisenberg E. (1980). Cooperative binding of myosin subfragment-1 to the actin-troponin-tropomyosin complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 77 2616–2620. 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta M. P., Samant S. A., Smith S. H., Shroff S. G. (2008). HDAC4 and PCAF bind to cardiac sarcomeres and play a role in regulating myofilament contractile activity. J. Biol. Chem. 283 10135–10146. 10.1074/jbc.M710277200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison S. M., Bers D. M. (1989). Influence of temperature on the calcium sensitivity of the myofilaments of skinned ventricular muscle from the rabbit. J. Gen. Physiol. 93 411–428. 10.1085/jgp.93.3.411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison S. M., Bers D. M. (1990). Modification of temperature dependence of myofilament Ca sensitivity by troponin C replacement. Am. J. Physiol. 258 C282–C288. 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.2.C282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorne D. J., Barns E. M., Parker L., Fuchs F. (1972). The effect of temperature on actomyosin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 267 190–202. 10.1016/0005-2728(72)90150-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haselgrove J. C. (1973). X-ray evidence for conformational changes in the myosin filaments of vertebrate striated muscle. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 37 341–352. 10.1016/0022-2836(75)90094-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill D. K. (1970). The effect of temperature on the resting tension of frog’s muscle in hypertonic solutions. J. Physiol. 208 741–756. 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiranandani N., Varian K. D., Monasky M. M., Janssen P. M. L. (2006). Frequency-dependent contractile response of isolated cardiac trabeculae under hypo-, normo-, and hyperthermic conditions. J. Appl. Physiol. 100 1727–1732. 10.1152/japplphysiol.01244.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley H. E. (1973). Structural changes in the actin- and myosin-containing filaments during contraction. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 37 361–376. 10.1101/sqb.1973.037.01.046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii S., Oyama K., Arai T., Itoh H., Shintani S. A., Suzuki M., et al. (2019). Microscopic heat pulses activate cardiac thin filaments. J. Gen. Physiol. 151 860–869. 10.1085/jgp.201812243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiwata S. (1978). Studies on the F-actin.tropomyosin.troponin complex. III. Effects of troponin components and calcium ion on the binding affinity between tropomyosin and F-actin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 534 350–357. 10.1016/0005-2795(78)90018-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiwata S., Shimamoto Y., Fukuda N. (2011). Contractile system of muscle as an auto-oscillator. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 105 187–198. 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2010.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen P. M. L., Stull L. B., Marbán E. (2002). Myofilament properties comprise the rate-limiting step for cardiac relaxation at body temperature in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 282 H499–H507. 10.1152/ajpheart.00595.2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagemoto T., Oyama K., Yamane M., Tsukamoto S., Kobirumaki-Shimozawa F., Li A., et al. (2018). Sarcomeric auto-oscillations in single myofibrils from the heart of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ. Hear. Fail. 11:e004333. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.004333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kentish J. C. (1984). The inhibitory effects of monovalent ions on force development in detergent-skinned ventricular muscle from guinea-pig. J. Physiol. 352 353–374. 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kentish J. C. (1986). The effects of inorganic phosphate and creatine phosphate on force production in skinned muscles from rat ventricle. J. Physiol. 370 585–604. 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp015952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobirumaki-Shimozawa F., Inoue T., Shintani S. A., Oyama K., Terui T., Minamisawa S., et al. (2014). Cardiac thin filament regulation and the Frank-Starling mechanism. J. Physiol. Sci. 64 221–232. 10.1007/s12576-014-0314-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremneva E. V., Nikolaeva O. P., Gusev N. B., Levitskij D. I., Levitsky D. I. (2003). Effects of troponin on thermal unfolding of actin-bound tropomyosin. Biokhimiya 68 976–984. 10.1023/A:1025043202615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara S., Sakai T. (1985). Effects of rapid cooling on mechanical and electrical responses in ventricular muscle of guinea-pig. J. Physiol. 361 361–378. 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman W., Craig R., Vibert P. (1994). Ca2 +-induced tropomyosin movement in Limulus thin filaments revealed by three-dimensional reconstruction. Nature 368 65–67. 10.1038/368065a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino A., Arai S., Hou Y., Degl’Innocenti A., Cappello V., Mazzolai B., et al. (2017). Gold nanoshell-mediated remote myotube activation. ACS Nano 11 2494–2508. 10.1021/acsnano.6b08202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matusovsky O. S., Mansson A., Persson M., Cheng Y. S., Rassier D. E. (2019). High-speed AFM reveals subsecond dynamics of cardiac thin filaments upon Ca2+ activation and heavy meromyosin binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116 16384–16393. 10.1073/pnas.1903228116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikane T., Araki J., Suzuki S., Mizuno J., Shimizu J., Mohri S., et al. (1999). O2 cost of contractility but not of mechanical energy increases with temperature in canine left ventricle. Am. J. Physiol. Hear. Circ. Physiol. 277 65–73. 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.1.h65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar N. C., Homsher E. (1990). The effect of phosphate and calcium on force generation in glycerinated rabbit skeletal muscle fibers. J. Biol. Chem. 265 20234–20240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mühlrad A., Hegyi G. (1965). The role of Ca2 + in the adenosine triphosphatase activity of myofibrils. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 105 341–351. 10.1016/s0926-6593(65)80158-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy R. A., Hasselbach W. (1968). Calcium ion-dependent myofibrillar adenosine triphosphatase activity correlated with the contractile response. Temperature-induced loss of calcium ion sensitivity. J. Biol. Chem. 243 5656–5662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obata K., Takeshita D., Morita H., Takaki M. (2018). Left ventricular mechanoenergetics in excised, cross-circulated rat hearts under hypo-, normo-, and hyperthermic conditions. Sci. Rep. 8:16246. 10.1038/s41598-018-34666-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuki I., Morimoto S. (2008). Troponin: Regulatory function and disorders. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 369 62–73. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orchard C. H., Kentish J. C. (1990). Effects of changes of pH on the contractile function of cardiac muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 258 C967–C981. 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.6.C967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyama K., Mizuno A., Shintani S. A., Itoh H., Serizawa T., Fukuda N., et al. (2012). Microscopic heat pulses induce contraction of cardiomyocytes without calcium transients. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 417 607–612. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadaki M., Holewinski R. J., Previs S. B., Martin T. G., Stachowski M. J., Li A., et al. (2018). Diabetes with heart failure increases methylglyoxal modifications in the sarcomere, which inhibit function. JCI Insight 3:e121264. 10.1172/jci.insight.121264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Protasi F., Shtifman A., Julian F. J., Allen P. D. (2004). All three ryanodine receptor isoforms generate rapid cooling responses in muscle cells. Am. J. of Physiol. Cell Physiol. 286 C662–C670. 10.1152/ajpcell.00081.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puglisi J. L., Bassani R. A., Bassani J. W., Amin J. N., Bers D. M. (1996). Temperature and relative contributions of Ca transport systems in cardiac myocyte relaxation. Am. J. Physiol. 270 H1772–H1778. 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.5.H1772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranatunga K. W. (1994). Thermal stress and Ca-independent contractile activation in mammalian skeletal muscle fibers at high temperatures. Biophys. J. 66 1531–1541. 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80944-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refinetti R. (2010). The circadian rhythm of body temperature. Front. Biosci. 15:564–594. 10.2741/3634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risi C., Eisner J., Belknap B., Heeley D. H., White H. D., Schröder G. F., et al. (2017). Ca2 +-induced movement of tropomyosin on native cardiac thin filaments revealed by cryoelectron microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114 6782–6787. 10.1073/pnas.1700868114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg H., Pollock N., Schiemann A., Bulger T., Stowell K. (2015). Malignant hyperthermia: a review. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 10:93. 10.1186/s13023-015-0310-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeki A., Goto Y., Hata K., Takasago T., Nishioka T., Suga H. (2000). Negative inotropism of hyperthermia increases oxygen cost of contractility in canine hearts. Am. J. Physiol. Hear. Circ. Physiol. 279 11–18. 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.6.h2855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltin B., Gagge A. P., Stolwijk J. A. (1968). Muscle temperature during submaximal exercise in man. J. Appl. Physiol. 25 679–688. 10.1152/jappl.1968.25.6.679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattock M. J., Bers D. M. (1987). Inotropic response to hypothermia and the temperature-dependence of ryanodine action in isolated rabbit and rat ventricular muscle: implications for excitation-contraction coupling. Circ. Res. 61 761–771. 10.1161/01.res.61.6.761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shutt R. H., Howlett S. E. (2008). Hypothermia increases the gain of excitation-contraction coupling in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 295 692–700. 10.1152/ajpcell.00287.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A., Hitchcock-DeGregori S. E. (2009). A peek into tropomyosin binding and unfolding on the actin filament. PLoS One 4:e6336. 10.1371/journal.pone.0006336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solaro R. J., Rarick H. M. (1998). Troponin and tropomyosin: proteins that switch on and tune in the activity of cardiac myofilaments. Circ. Res. 83 471–480. 10.1161/01.RES.83.5.471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H., Oosawa F. (1971). The effect of temperature on the interaction between F-actin and tropomyosin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 253 274–283. 10.1016/0005-2728(71)90253-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trybus K. M., Taylor E. W. (1980). Kinetic studies of the cooperative binding of subfragment 1 to regulated actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 77 7209–7213. 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veltri T., de Oliveira G. A. P., Bienkiewicz E. A., Palhano F. L., Marques M., de A., et al. (2017). Amide hydrogens reveal a temperature-dependent structural transition that enhances site-II Ca2 +-binding affinity in a C-domain mutant of cardiac troponin C. Sci. Rep. 7:691. 10.1038/s41598-017-00777-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon H. M. (1899). Heat rigor in cold-blooded animals. J. Physiol. 24 239–287. 10.1113/jphysiol.1899.sp000757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vibert P., Craig R., Lehman W. (1997). Steric-model for activation of muscle thin filaments. J. Mol. Biol. 266 8–14. 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C., Craig R., Tobacman L., Horowitz R., Lehman W. (1999). Tropomyosin positions in regulated thin filaments revealed by cryoelectron microscopy. Biophys. J. 77 985–992. 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76949-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]