Abstract

An increasing number of original studies suggest the relevance of assessing mental health; however, there has been a lack of knowledge about the magnitude of Common Mental Disorders (CMD) in adolescents worldwide. This study aimed to estimate the prevalence of CMD in adolescents, from the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12). Only studies composed by adolescents (10 to 19 years old) that evaluated the CMD prevalence according to the GHQ-12 were considered. The studies were searched in Medline, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, Lilacs, Adolec, Google Scholar, PsycINFO and Proquest. In addition, the reference lists of relevant reports were screened to identify potentially eligible articles. Studies were selected by independent reviewers, who also extracted data and assessed risk of bias. Meta-analyses were performed to summarize the prevalence of CMD and estimate heterogeneity across studies. A total of 43 studies were included. Among studies that adopted the cut-off point of 3, the prevalence of CMD was 31.0% (CI 95% 28.0–34.0; I2 = 97.5%) and was more prevalent among girls. In studies that used the cut-off point of 4, the prevalence of CMD was 25.0% (CI 95% 19.0–32.0; I2 = 99.8%). Global prevalence of CMD in adolescents was 25.0% and 31.0%, using the GHQ cut-off point of 4 and 3, respectively. These results point to the need to include mental health as an important component of health in adolescence and to the need to include CMD screening as a first step in the prevention and control of mental disorders.

Introduction

Common Mental Disorders (CMD) refer to depressive and anxiety disorders and are distinct from the feeling of sadness, stress or fear that anyone can experience at some moment in life. Despite some methodological differences in the epidemiological studies, it is estimated that 4.4% and 3.6% of the world adult population suffers from depressive and anxiety disorders, respectively [1]. CMD can affect health and quality of life, and it is noted that CMD affect people at an early age [2].

The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors (GBD) study is a comprehensive study that evaluates incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability (YLDs), which in its most recent study evaluated the period from 1990 to 2017 for 195 countries and territories, and identified that the burden of mental disorders is present for males and females and across all age groups. The findings of the GDB indicate that mental disorders have consistently formed more than 14% of age-standardized YLDs for nearly three decades, and have greater than 10% prevalence in all 21 GBD regions [3]. Mental disorders are not often correctly identified and have negative consequences on people's health.

At the population level the use of self-report psychiatric screening instruments, such as the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), has been recommended to track CMD, also known as psychological distress/problems or psychiatric morbidity or non-psychotic mental illnesses [4]. The GHQ-12 is a short and self-report form to identify people with psychological distress or CMD [5,6]. This validated instrument comprising a multidimensional evaluation based in three factors: anxiety and depression, social dysfunctions and loss of confidence [7] and can be applied in individuals of different ages [8].

Adolescence, defined as a transitional phase between ages 10 and 19 [9] is generally perceived as a phase of life with no health problems. However, approximately 20% of adolescents experience a mental health problem, most commonly depression or anxiety [10].

Although there are preliminary data on the severity of these conditions among adolescents [11], there has been a lack of knowledge about the magnitude of CMD in adolescents worldwide. There was a systematic review of the global prevalence of CMD, published in 2014, which incorporated studies from 1980 to 2013 that surveyed people aged 16 to 65 and using diagnostic criteria other than GHQ. In addition, from this study it was not possible to identify the prevalence of CMD in adolescents [12]. In this context, a systematic review of the literature was carried out to estimate the prevalence of CMD in adolescents around the world, from item 12 of the GHQ.

Materials and methods

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analyses PRISMA checklist [13] and for meta-analyses followed Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) [14] guidelines.

Protocol and registration

The systematic review protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), registration number CRD42018094763.

Eligibility criteria

The present study included observational studies. Only studies that assessed the prevalence of CMD according to GHQ-12 in adolescents (10 to 19 years old) were considered for retention. In studies that evaluated adolescents and also individuals outside the age group of interest for this review, an attempt was made to identify only those eligible through the information contained in the article or by contacting authors.

Moreover, no restrictions of language, publication date or status were applied. Studies of specific groups such as obese or diabetic individuals, adolescents in treatment of any health condition, college students, people who had traumatic experiences, pregnant teenagers and people with physical disabilities were not eligible. The ineligibility criterion considered those conditions that predispose to a higher risk of CMD, such as life events that presumably increase the chances of having feelings of stress, depression or anxiety. For example, among college students depression rates could be substantially higher than those found in the general population, probably because they experience moments of stress related to studies or future choices involving the profession phase of life [15]. Systematic reviews, interventional studies or ecological estimates were also not included.

Information sources

A systematic search of the following databases was conducted to identify relevant studies: Medline, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, Lilacs and Adolec. A partial grey literature search was also performed in Google Scholar, PsycINFO and Proquest Dissertation and Theses. The Google Scholar search was limited to the first 200 most relevant articles. The search was conducted on December 1, 2018 and updated in April 1, 2019. Additional articles, were hand-searched in selected articles to identify potentially eligible studies not retrieved by the database search. The search strategy was reviewed by two researchers, one of them with extensive experience in systematic reviews, according to the criteria of the checklist of the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS checklist) [16].

The following strategy was adapted for the databases: (Adolescent OR Teenager OR Child OR Young OR Teen OR Youth OR Juvenile OR Adolescence OR Younger) AND (“General Health Questionnaire” OR GHQ OR GHQ-12) AND (“common mental disorders” OR CMD OR Anxiety OR anxious OR depression OR dysthymia OR “generalized anxiety disorder” OR “panic disorder” OR phobia OR “social anxiety disorder” OR “obsessive-compulsive disorder” OR “mental disorder” OR “mental health” OR "Psychological stress" OR "Life Stress" OR "Psychologic Stress" OR "Mental suffering" OR Anguish OR "Emotional stress") AND (Survey OR “Cross-sectional studies” OR Prevalence OR frequency OR "Cross-sectional" OR Observational). More information on the search strategies is provided in S1 Appendix. The Covidence Software (Cochrane Collaboration software®, Melbourne, Australia) was used to remove duplicate references and for the screening procedure, applied independently.

Data collection process

The study selection process was carried out in two stages. First, the articles were selected based on their titles and abstracts, followed by a full text assessment. These two stages were carried by two independent authors (SAS and SUS) and the records that did not meet the inclusion criteria were discarded. The disagreements were resolved by consensus and counted on the participation of a third author (DBR).

Data were extracted in duplicate by authors and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The following data were collected: authors, year of publication, year of research, country, study design, age (mean or range), sample size (sex), GHQ cut-off point and outcome of the studies (prevalence of CMD). The corresponding authors of the studies were contacted (at least two attempts of contact) in case of unavailable data.

The 12-item version of the GHQ has psychometric properties comparable to those of the longer versions of the questionnaire and the items of this instrument describe positive and negative aspects of mental health in the last two weeks and present a scale with four response options. The difference in the scale for positive and negative items indicates that the higher the score, the higher level of psychiatric disorders. The studies show great variation in the scoring methods for the GHQ, with scales ranging from zero to 12 or zero to 36.

Risk of bias within individual studies

The critical appraisal tool, recommended by The Joanna Briggs Institute for cross-sectional studies, was used to assess the risk of bias. The purpose of this appraisal is to assess the methodological quality of a study and to determine the possibility of bias in its design, conduct and analysis. This instrument consists of nine questions answered as “yes”, “no”, “unclear”, or “not applicable” [17].

For this study, when all items were answered “yes”, the risk of bias were considered low, and if any item were classified as “no” or “unclear”, a high risk of bias were expected. No scores were assigned; results were expressed by the frequency of each classification of the evaluation parameters. These ratings were not used as a criterion for study eligibility.

Summary measures and data analysis

The primary outcome was the prevalence of CMD, with a confidence interval of 95% (CI 95%). We estimated the summary measures for the total population and subgroups defined by sex, risk of bias and income level according to the World Bank classification [18]. The meta-analyses were calculated using a random-effect model and weighed by the inverse of the variance. The heterogeneity was evaluated by the Chi-square test with significance of p<0.10, and its magnitude was determined by the I-squared (I2) [19].

Meta-regressions were performed in order to identify possible causes of heterogeneity using the Knapp and Hartung test [20] with the following variables: risk of bias, sample size, proportion of female adolescent, year of study and income level. The small-study effect by visual inspection of the funnel graph and Egger's test [21] was also evaluated.

Analyzes were performed with the "Metaprop" command of the Stata software (version 14.0), adopting p<0.05.

Results

Study selection

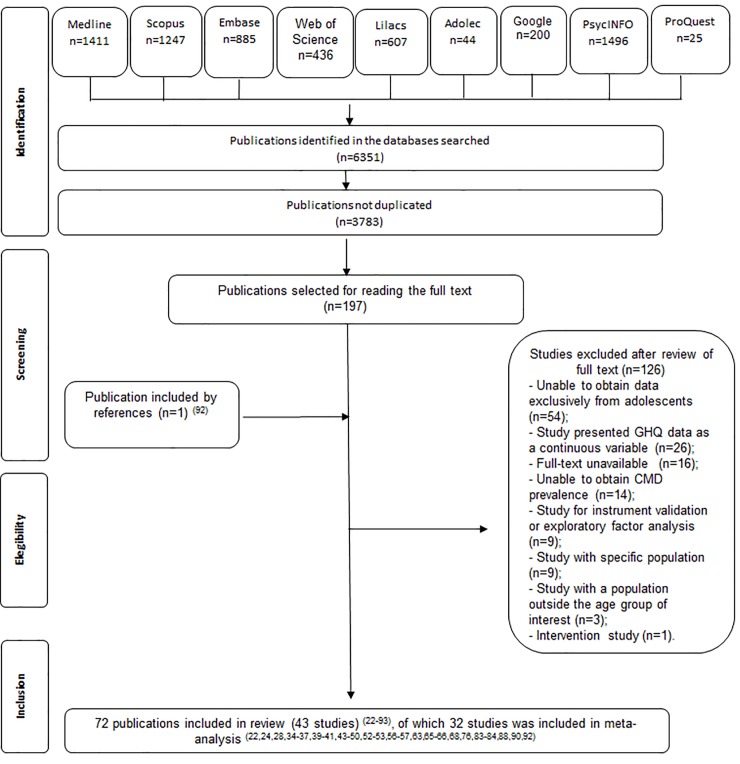

A total of 6 351 articles were initially found in the nine electronic databases, including grey literature. After removing the duplicates, the titles and abstracts of 3 783 articles were screened, and 197 potentially relevant studies were selected for full-text reading. An additional record was selected from the reference lists of the fully read articles. A total of 126 articles were excluded for nominated reasons (see S1 Table). Forty-three studies (reported in 72 articles) [22–93] were therefore selected for inclusion in this review. The screening process is detailed in Fig 1.

Fig 1. Flow chart of systematic review procedure for illustrating search results, selection and inclusion of studies.

*Adapted from PRISMA.

Study characteristics

Table 1 shows a summary of the study characteristics. A total of 43 studies (200 980 participants; 19 countries) were included. The CMD prevalence studies were conducted in Asia [26,27,34,39,40,45,48–50,52–54,57,70,89,90], America [38,41,44,84], Africa [22], Europe [24,28,32,35–37,43,46,47,56,63,65,68,71,76,88,92] and Oceania [66,83]. The majority of studies (n = 33) had a cross-sectional design.

Table 1. Summary of characteristics of included studies.

| Author, year | Year of research | Country | Study design | Age (mean or range) | Sample size (sex) | GHQα cut-off point |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amoran, 20051 | NI | Nigeria | Cross-sectional | 15 to 19 | 197 | 3b |

| Arun, 2009 | NI | India | Cross-sectional | 12 to 19 | 2 402 (boys = 1 371; girls = 1 031) | 3b |

| Augustine, 2014 | 2009–2010 | India | Cross-sectional | 15 to 19 | 145 (all boys) | 3b |

| Ballbè, 20152 | 2011–2012 | Spain | Cross-sectional | 15 to 19 | 740 (boys = 396; girls = 344) | 3b |

| Bansal, 2009 | NI | NI | Cross-sectional | NI (9th grade students) | 125 | 14c |

| Cheung, 2011 | NI | China | Cross-sectional | 14.70±2.02 | 719 (boys = 434; girls = 285) | 11c |

| Czaba£a, 20053 | 2002 | Poland | Cross-sectional | 13.8 | 1 123 (boys = 521; girls = 600) | 3b |

| Dzhambov, 20174 | 2016 | Bulgaria | Cross-sectional | 15 to 19 | 557 (boys = 408; girls = 149) | 3b |

| Emami, 2007 | 2004 | Iran | Cross-sectional | 17 to 18 | 4 310 (boys = 1 923; girls = 2 387) | 7b |

| Fernandes, 2013 | 2006 | India | Cross-sectional | 16 to 18 | 1 488 | 5b |

| Gale, 20045 | 1986 | United Kingdom | Longitudinal | 16 (range not available) | 5 187 (boys = 2 222; girls = 2 965) | 3b |

| Gecková, 20036 | 1998 | Slovakia | Cross-sectional | 15 (range not available) | 2 616 (boys = 1 369; girls = 1 243) | 2/3b,c |

| Glendinning, 2007 | 2002–2003 | Russia | Cross-sectional | 14 to 15 | 626 | 4b |

| Gray, 2008 | 1998 and 2003 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 13 to 15 | 1 253 | 4b |

| Green, 2018 | 2017–2013 | United Kingdom | Longitudinal | 16 (range not available) | 1 204 (boys = 619; girls = 585) | 3b |

| Hamilton, 2009 | 2005 | Canada | Cross-sectional | 12 to 19 | 4 078 (boys = 2 092; girls = 1 986) | 6b |

| Hori, 2016 | 2011 | Japan | Cross-sectional | 12 to 19 | 744 (boys = 373; girls = 371) | 4b |

| Kaneita, 2009 | 2004 | Japan | Longitudinal | 13 to 15 | 516 (boys = 294; girls = 222) | 4b |

| Lopes, 20167 | 2013–2014 | Brazil | Cross-sectional | 12 to 17 | 74 589 (boys = 33 364; girls = 41 225) | 3b |

| Mäkelä, 2015 | 2008 | Finland | Cross-sectional | 15 to 19 | 225 (boys = 102; girls = 123) | 4b |

| Mann, 2011 | 2007 | Canada | Cross-sectional | 12 to 19 | 3 311 (boys = 1 566; girls = 1 745) | 3b |

| McNamee, 2008 | 2005 | Ireland | Cross-sectional | 16 (range not available) | 868 (boys = 352; girls = 516) | 4b |

| Miller, 2018 | 2018 | United Kingdom | Longitudinal | 13 to 17 | 407 (boys = 204; girls = 203) | 4b |

| Munezawa, 2009 | NI | Japan | Cross-sectional | 12 to 14 | 916 (boys = 568; girls = 348) | 4b |

| Nakazawa, 2011 | 2008 | Japan | Cross-sectional | 12 to 15 | 4 864 (boys = 2,429; girls = 2,435) | 4b |

| Nishida, 20088 | 2006 | Japan | Cross-sectional | 12 to 15 | 4 894 (boys = 2 523; girls = 2 371) | 4b |

| Nur, 2012 | 2009–2010 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | 15 to 19 | 244 (all girls) | 4b |

| Ojio, 2016 | 2006 | Japan | Cross-sectional | 12 to 18 | 15 637 (boys = 7 953; girls = 7 684) | 4b |

| Oshima, 20109 | 2009 | Japan | Cross-sectional | 12 to 18 | 341 (boys = 173; girls = 168) | 5b |

| Oshima, 201210 | 2008–2009 | Japan | Cross-sectional | 12 to 18 | 17 920 (boys = 8 886; girls = 9 034) | 4b |

| Padrón, 201211 | 2008–2009 | Spain | Cross-sectional | 15 to 17 | 4 054 (boys = 1 951; girls = 2 103) | 3b |

| Pisarska, 2011 | 2004 | Poland | Cross-sectional | 15 to 16 | 722 (boys = 383; girls = 335) | 3b |

| Rickwood, 1996 | 1994 | Australia | Longitudinal | 16 to 19 | 4 163 (boys = 1 988; girls = 2 175) | 4b |

| Rothon, 201212 | 2005 | United Kingdom | Longitudinal | 14 to 15 | 13 539 (boys = 7 852; girls = 7 579) | 4b |

| Roy, 2014 | 2009–2010 | India | Cross-sectional | 14 to 15 (around 80% of sample) | 400 (boys = 200; girls = 200) | 15c |

| Sweeting, 200913 | 1987 | United Kingdom | Longitudinal | 15.8±3.5 months | 505 | 2/3; 3/4;4/5b |

| Sweeting, 200913 | 1999 | United Kingdom | Longitudinal | 15.5±3.6 months | 2 196 | 2/3; 3/4;4/5b |

| Sweeting, 200913 | 2006 | United Kingdom | Longitudinal | 15.5±3.8 months | 3 194 | 2/3; 3/4;4/5b |

| Thomson, 201814 | 1991–2014 | United Kingdom | Cross-sectional | 16 to 19 | 11 397 (boys = 5 376; girls = 6 021) | 4b |

| Trainor, 2010 | 2001 | Australia | Longitudinal | 13 to 17 | 947 (boys = 390; girls = 557) | 4b |

| Trinh, 201515 | 2009 | Canada | Cross-sectional | 15,8 | 2 660 (boys = 1 236; girls = 1 397) | 3b |

| Van Droogenbroeck, 2018 | 2008 | Belgium | Cross sectional | 15 to 19 | 680 (boys = 341; girls = 339) | 4b |

| Yusoff, 2010 | NI | Malaysia | Cross-sectional | 16 (range not available) | 90 (boys = 40; girls = 50) | 4b |

NI: Not informed.

αGHQ: General Health Questionnaire, 12 items.

bThe score range was 0–12.

cThe score range was 0–36.

1Amoran, 2007

2(Basterra, 2017; Gotsens, 2015)

3Bobrowski, 2007

4Dzhambov, 2018

5(Steptoe, 1996; Collishaw, 2010; Morgan, 2012)

6Gecková, 2004

7Telo, 2018

8Nishida, 2010

9Yamasaki, 2018

10(Kinoshita, 2011; Ando, 2013; Shiraishi, 2014; Kitawaga, 2017; Morokuma, 2017)

11Padrón, 2014

12Hale, 2014

13(West, 2003; Young, 2004; Sweeting, 2008; Sweeting 2010)

14(Fagg, 2008; Lang, 2011; Maheswaran, 2015; Pitchfort, 2016 and 2018)

15(Hamilton, 2011; Arbour-Nicitopoulos, 2012; Isaranuwatchai, 2014).

For the purpose of comparing the studies, we selected only those that presented the score scale from zero to 12, totaling 32 studies classified by 3 or 4 diagnostic cut-off points. Thus for the set of studies that adopted the cut-off point of 3 or more symptoms of the GHQ-12, the sample size varied from 145 adolescents in India [45] to 74 589 in Brazil [41], these studies included 96 842 adolescents between the ages of 12 and 19 years. In the set of studies with cut-off point of 4 or more symptoms, it ranged from 90 adolescents in Malaysia [90] to 17 920 in Japan [57] and the total sample was 79 892 adolescents aged 12 to 19 years.

Results of individual studies and synthesis of results

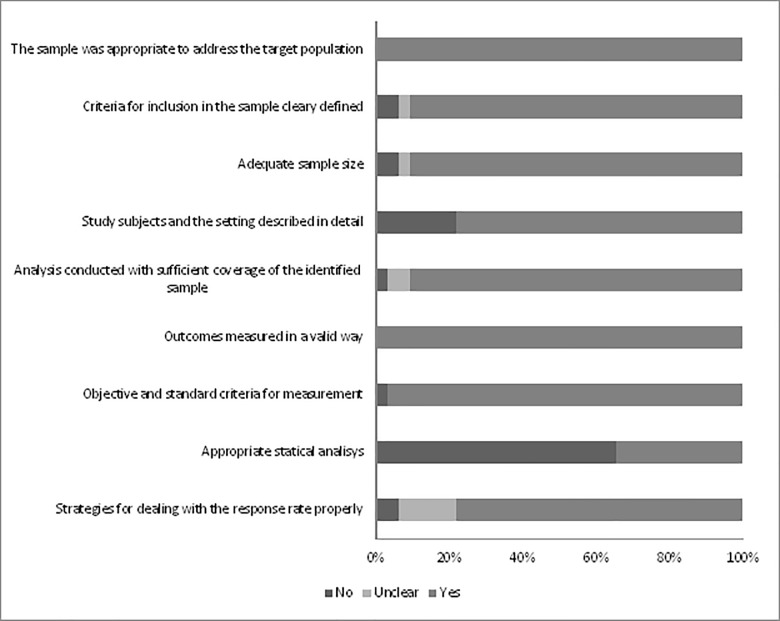

Only six (18.8%) studies were considered to be of low risk of bias. Considering that the GHQ is a self-administered instrument composed of validated questions and translated in several languages, the parameter that deals with the identification of the outcomes measured in a valid way was met by all the studies.

Two parameters were not met by most studies: (1) appropriate statistical analysis; and (2) study subjects and the setting described in detail (Fig 2 and Table 2). It is important to emphasize that the critical appraisal tool recommends that the numerator and the denominator be clearly reported, and that the percentages should be given with confidence intervals, so in the methods section there must be enough details to identify the analytical technique used and how specific variables were measured in the study. In addition, the study sample should be described in enough detail so that other researchers can determine if it is comparable to the population of interest to them. It is worth mentioning that some studies have reported the year of data collection and characteristics of the study population.

Fig 2. Risk of bias in the included studies (The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal checklist for prevalence studies).

Table 2. Risk of bias for each individual study assessed by Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal checklist for prevalence studies.

| Studies | Criteria | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1* | 2* | 3* | 4* | 5* | 6* | 7* | 8* | 9* | |

| Amoran, 2005 | Y | Y | N | Y | U | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Arun, 2009 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Augustine, 2014 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | U |

| Ballbè, 2015 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Czaba£a, 2005 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Droogenbroeck, 2018 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Dzhambov, 2017 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Fagg, 2008 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Gale, 2004 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Glendinning, 2007 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Green, 2018 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Hori, 2016 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Kaneita, 2009 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Lopes, 2016 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Mäkelä, 2014 | Y | U | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Mann, 2011 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| McNamee, 2008 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N |

| Miller, 2018 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | U |

| Munezawa, 2009 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Nakazawa, 2011 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Nishida, 2008 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Nur, 2012 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Ojio, 2016 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Oshima, 2012 | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Padrón, 2012 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Pisarska, 2011 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Rothon, 2012 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

| Thomson, 2018 | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | N | U |

| Trainor, 2010 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U |

| Trinh, 2015 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Yusoff, 2010 | Y | N | U | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y |

| Rickwood, 1996 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y |

*Y = Yes, N = No, U = Unclear, NA = Not applicable

1*The sample was appropriate to address the target population

2*Criteria for inclusion in the sample cleary defined

3*Adequate sample size

4*Study subjects and the setting described in detail

5*Analysis conducted with sufficient coverage of the identified sample

6*Outcomes measured in a valid way

7*Objective and standard criteria for measurement

8*Appropriate statistical analysis

9*Strategies for dealing with the response rate properly

Results of individual studies

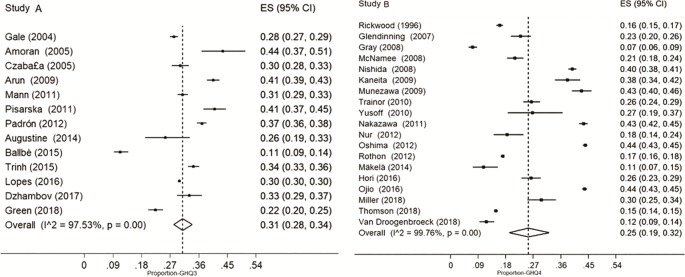

Among those that adopted the cut-off point of 3 or more symptoms, the prevalence of CMD was 31.0% (CI95% 28.0–34.0; I2 = 97.5%). In studies that used the cut-off point of 4 or more symptoms, the prevalence of CMD was 25.0% (CI 95% 19.0–32.0; I2 = 99.8%) (Fig 3). In the subgroup analysis, the heterogeneity remained high and it was observed that CMD is higher in female adolescents when considered the cut-off point 3 (Table 3).

Fig 3.

Common mental disorders prevalence in adolescents in studies with cut-off point 3 or more symptoms (A) and cut-off point 4 or more symptoms (B).

Table 3. Prevalence of common mental disorders, by subgroups, in adolescents.

| Subgroups | Number of studies | Number of participants | Prevalence (%) | Confidence interval 95% | I2(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cut-off 3 or more symptoms | |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 10 | 42 192 | 23.0 | 21.0–26.0 | 92.9* |

| Female | 9 | 50 863 | 38.0 | 34.0–42.0 | 96.9* |

| Risk of bias | |||||

| High | 8 | 11 506 | 32.0 | 29.0–35.0 | 97.3* |

| Low | 5 | 85 336 | 30.0 | 17.0–45.0 | 98.2* |

| Income Level | |||||

| High income | 8 | 19 247 | 29.0 | 24.0–34.0 | 98.0* |

| Low income | 5 | 79 745 | 35.0 | 28.0–41.0 | 96.9* |

| Cut-off 4 or more symptoms | |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 9 | 26 006 | 14.0 | 7.0–22.0 | 99.6* |

| Female | 9 | 26 881 | 27.0 | 15.0–40.0 | 99.8* |

| Risk of bias | |||||

| High | 18 | 79 648 | 26.0 | 19.0–33.0 | 99.8* |

| Low | 1 | 244 | 18.0 | 14.0–24.0 | - |

| Income Level | |||||

| High income | 16 | 78 932 | 26.0 | 19.0–33.0 | 99.8* |

| Low income | 3 | 960 | 22.0 | 18.0–26.0 | - |

*p < 0.001.

In the meta-regression, the high heterogeneity could not be explained by the studied variables: sex, income level and year of publication (p>0.05; data not shown).

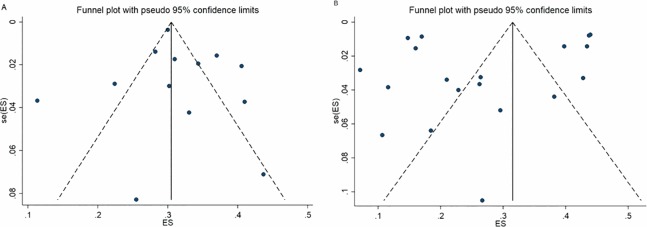

The funnel graph was able to show the asymmetry between the studies, with greater representation of large studies (Fig 4). Graph A shows the studies that adopted cut-off point 3 and graph B, those that used cut-off point 4. Both illustrate that there is an effect of small studies and these findings were confirmed by the Egger's Test (p<0.001).

Fig 4.

Funnel graph on the prevalence of common mental disorders in adolescents in studies with cut-off point 3 or more symptoms (A) and cut-off point 4 or more symptoms (B). Egger´s test: p<0.001.

Discussion

This systematic review was able to reveal the magnitude of CMD in adolescents from all over the world. When presented at this stage of life, CMD can have negative consequences throughout the future years. The problem is common and worrying, so much has been widely studied since the 1980s [12] however, they refer to studies with diverse populations and with different ways of identification of CMD.

Mental health can be influenced by several factors. Socioeconomic characteristics [38,94–97]; characteristics of lifestyle [43,56,64,83,98–100] [43]and also characteristics related to affective relationships [101–103], have been the focuses of studies already performed in adolescents.

Our meta-analysis revealed that very large studies were conducted in Japan and United Kingdom. It was reported that children and adolescents in Japan have greater depressive tendencies and this condition may be growing each year in several countries [104]. In the United Kingdom, the assessment and monitoring of psychological distress among adolescents is a common practice and generally performed in longitudinal studies for more than two decades [105].The evidence indicates that the relationship between culture or personal values and mental disorders differs across cultures and age groups [106]. An approach that takes into account the differences in social and cultural contexts is necessary to understand the occurrence and phenomenology of CMD in epidemiological studies, since there is a relationship between them but that needs to be better clarifies in future studies.

Although with some degree of methodological issue in most studies, since less than 20% of the studies presented low risk of bias, the results of this study indicate that CMD affect girls more, considering only the studies that adopted cut-off point 3. Permanent concern with physical appearance, body dissatisfaction, exposure to sexualization may be one of the reasons that affect girls' mental health [107].

Another factor that apparently influences the presence of CMD is income level. Even though the results presented in this systematic review showed no difference between income level of the countries and CMD, further studies with this focus are needed in order to deepen the knowledge about the subject. Longitudinal studies such as the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) and Longitudinal Study of Young People in England (LYSPE) demonstrate the impact of economic recession and poverty in populations by strong associations between socioeconomic variables and health outcomes [76,108–111].

Although the GHQ is a validated instrument for detecting CMD, the scoring scale and cut-off point are not consensual, which impairs comparison among studies. Meta-analyses in the present study were based on cut-off points 3 and 4, since they were more frequent among the studies.

In relation to age, studies are commonly defined to be representative of the population aged 15 years or more, however, it is also important to investigate the phenomenon of CMD among the younger population (10 to 14 years), since global epidemiological data consistently report that up to 20% of children and adolescents suffer from a disabling mental illness [112]. Particular attention should be paid to the most vulnerable adolescent population in order to create strategies based on scientific evidence [113]. This systematic review revealed the severity of the problem by the worldwide high prevalence of CMD among adolescents, using a standardized criterion of measurement, the GHQ-12.

Study limitations

In this review some of the eligible studies showed association data and did not present the prevalence and the respective confidence intervals, nor did they present the description of the evaluated population. It is possible that this review did not include all relevant publications, either because the articles did not present sufficient information or because the authors were not located or, finally, because of unanswered communication attempts.

It is observed that the different cut-off points for the GHQ-12 adopted in the original studies were a complicating factor in the identification of cases of CMD and in the comparison among studies. Even if measures were taken to combine studies that were as comparable as possible, this review included studies conducted at different times and places and with varying methodologies. These characteristics are revealed in the heterogeneity between the studies, typically found in cross-sectional studies and, therefore, we performed a subgroup analysis and a meta-regression, but without success.

Strengths of the study

In the elaboration of this systematic review, some steps were considered as the registration of protocol in PROSPERO, the use of the PRESS checklist, blind selection of studies, the adoption of updated analytical methods and a search strategy that enabled the capture of a large numbers of studies. An extensive search for studies was carried out in the literature sources, the grey literature, and the reference lists of the eligible articles. When necessary, the authors of potentially eligible studies were contacted to obtain extra data to carry out the meta-analyses. Moreover, this systematic review followed the PRISMA tool guide and the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) [14].

Conclusion

The global prevalence of CMD in adolescents was 25.0% and 31.0%, using the GHQ cut-off point of 4 and 3, respectively. CMD was more prevalent among girls when observing studies that adopted a 3 cut-off point. These results point to the need to include mental health as an important component of health in adolescence and to the need to include CMD screening as a first step in the prevention and control of mental disorders.

Supporting information

(DOC)

(DOC)

(DOC)

(XLSX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.World Health Organization; Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates WHO World Heal Organ; [Internet]. 2017;1–24. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/254610/1/WHO-MSD-MER-2017.2-eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNICEF. The United NAtions Childre´s Fund. Adolescence: A Time That Matters [Internet]. 2002. 7–44 p. Available from: www.unicef.org

- 3.James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–858. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldberg D. A bio-social model for common mental disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1994;385:66–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb05916.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldberg DP, Gater R, Sartorius N, Ustun TB, Piccinelli M, Gureje O, et al. The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol Med. 1997;27(1):191–7. 10.1017/s0033291796004242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gnambs T, Staufenbiel T. The structure of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12): two meta-analytic factor analyses. Health Psychol Rev [Internet]. 2018;12(2):179–94. Available from: 10.1080/17437199.2018.1426484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graetz B. Multidimensional properties of the General Health Questionnaire. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1991;26(3):132–8. 10.1007/bf00782952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberg D; Rickels K; Downing R. and Hesbacher P. A comparison of two psychiatric screening tests. Br J Psychiatry. 1976; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Adolescence: The Critical Phase. World Health Organization; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. Adolescent mental health—Mapping actions of nongovernmental organizations and other international development organizations WHO World Heal Organ; 2012;50. [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization; Mental health atlas Bulletin of the World Health Organization; 2014. 76 p. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, Chey T, Jackson JW, Patel V, et al. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):476–93. 10.1093/ije/dyu038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Altman D, Antes G, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;7(9):889–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;283(15):2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ibrahim AK, Kelly SJ, Adams CE, Glazebrook C. A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. J Psychiatr Res [Internet]. 2013;47(3):391–400. Available from: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. J Clin Epidemiol [Internet]. 2016;75:40–6. Available from: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Joanna Briggs Institute. The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews—Checklist for Prevalence Studies. Crit Apprais Checkl Preval Stud. 2017;7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.The World Bank Group. World Development Indicators 2017. 2017;10.

- 19.Rodrigues C L, Ziegelmann P K. Metánalise: Um guia prático. Rev HCPA, editor. Rev HCPA [Internet]. 2010;(1):54 Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10183/24862 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knapp G, Hartung J. Improved tests for a random effects meta-regression with a single covariate. Stat Med. 2003;22(17):2693–710. 10.1002/sim.1482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, Terrin N, Jones DR, Lau J, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343(7818):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amoran OE, Lawoyin TO, Oni OO. Risk factors associated with mental illness in Oyo State, Nigeria: A community based study. Ann Gen Psychiatry [Internet]. 2005;4:19 Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1351179&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract 10.1186/1744-859X-4-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amoran O, Lawoyin T, Lasebikan V. Prevalence of depression among adults in Oyo State, Nigeria: A comparative study of rural and urban communities. Aust J Rural Health [Internet]. 2007. [cited 2018 Apr 23];15(3):211–5. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1440-1584.2006.00794.x/full [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dzhambov A, Tilov B, Markevych I, Dimitrova D. Residential road traffic noise and general mental health in youth: The role of noise annoyance, neighborhood restorative quality, physical activity, and social cohesion as potential mediators. Environ Int [Internet]. 2017;109(July):1–9. Available from: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dzhambov AM, Markevych I, Hartig T, Tilov B, Arabadzhiev Z, Stoyanov D, et al. Multiple pathways link urban green- and bluespace to mental health in young adults. Environ Res [Internet]. 2018;166(May):223–33. Available from: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emami H, Ghazinour M, Rezaeishiraz H, Richter J. Mental Health of Adolescents in Tehran, Iran. J Adolesc Heal [Internet]. 2007. December [cited 2018 Apr 26];41(6):571–6. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1054139X07002704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernandes AC, Hayes RD, Patel V. Abuse and other correlates of common mental disorders in youth: a cross-sectional study in Goa, India. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol [Internet]. 2013. April [cited 2018 Apr 26];48(4):515–23. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00127-012-0614-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gale CR, Martyn CN. Birth weight and later risk of depression in a national birth cohort. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184(January):28–33. 10.1192/bjp.184.1.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steptoe A, Butler N. Sports participation and emotional wellbeing in adolescents. Lancet. 1996;347(9018):1789–92. 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)91616-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collishaw S, Maughan B, Natarajan L, Pickles A. Trends in adolescent emotional problems in England: A comparison of two national cohorts twenty years apart. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip [Internet]. 2010. [cited 2018 Apr 23];51(8):885–94. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02252.x/full [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morgan Z, Brugha T, Fryers T, Stewart-Brown S. The effects of parent-child relationships on later life mental health status in two national birth cohorts. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol [Internet]. 2012. November 12 [cited 2018 Apr 23];47(11):1707–15. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00127-012-0481-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gecková A; Van Dijk JP, Stewart R; Groothoff J W; Post D. Influence of social support on health among gender and socio-economic groups of adolescents. Eur J Public Health [Internet]. 2003. [cited 2018 Apr 23];13(1):44–50. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/eurpub/article-abstract/13/1/44/488196 10.1093/eurpub/13.1.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geckova AM, van Dijk JP, Zezula I, Tuinstra J, Groothoff JW, Post D. Socio-economic differences in health among Slovak adolescents. Soz Praventivmed. 2004;49(1):26–35. 10.1007/s00038-003-2050-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arun P, Chavan B. Stress and suicidal ideas in adolescent students in Chandigarh. Indian J Med Sci [Internet]. 2009;63(7):281 Available from: http://www.indianjmedsci.org/text.asp?2009/63/7/281/55112 10.4103/0019-5359.55112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glendinning A, West P. Young people’s mental health in context: Comparing life in the city and small communities in Siberia. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(6):1180–91. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gray L, Leyland AH. Overweight status and psychological well-being in adolescent boys and girls: A multilevel analysis. Eur J Public Health. 2008;18(6):616–21. 10.1093/eurpub/ckn044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Green M J; Stritzel H; Smith C; Popham F; Crosnoe R. Timing of poverty in childhood and adolescent health: Evidence from the US and UK. Soc Sci Med. 2018;197:136–43. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamilton HA, Noh S, Adlaf EM. Perceived financial status, health, and maladjustment in adolescence. Soc Sci Med [Internet]. 2009. April [cited 2018 Apr 26];68(8):1527–34. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0277953609000471 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hori D, Tsujiguchi H, Kambayashi Y, Hamagishi T, Kitaoka M, Mitoma J, et al. The associations between lifestyles and mental health using the General Health Questionnaire 12-items are different dependently on age and sex: a population-based cross-sectional study in Kanazawa, Japan. Environ Health Prev Med. 2016;21(6):410–21. 10.1007/s12199-016-0541-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaneita Y, Yokoyama E, Harano S, Tamaki T, Suzuki H, Munezawa T, et al. Associations between sleep disturbance and mental health status: A longitudinal study of Japanese junior high school students. Sleep Med [Internet]. 2009. August [cited 2018 Apr 23];10(7):780–6. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1389945708002700 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lopes CS; Abreu GA; Santos DF; Menezes PR; Carvalho KMB; Cunha CF; et al. ERICA: Prevalence of common mental disorders in Brazilian adolescents. Rev Saude Publica. 2016;50(supl 1):1s–9s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Telo GH, Cureau F V, Lopes CS, Schaan BD. Common mental disorders in adolescents with and without type 1 diabetes: Reported occurrence from a countrywide survey. Diabetes Res Clin Pract [Internet]. 2018. January 1 [cited 2019 May 4];135:192–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29155124 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.10.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Makela P; Raitasalo K; Wahlbeck K. Mental health and alcohol use: A cross-sectional study of the Finnish general population. Eur J Public Health [Internet]. 2015. April 1 [cited 2018 Apr 26];25(2):225–31. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/eurpub/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/eurpub/cku133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mann RE; Paglia-Boak A; Adlaf EM; Beitchman J; Wolfe D; Wekerle C; et al. Estimating the Prevalence of Anxiety and Mood Disorders in an Adolescent General Population: An Evaluation of the GHQ12. Int J Ment Health Addict [Internet]. 2011. August 27 [cited 2018 Apr 23];9(4):410–20. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11469-011-9334-5 [Google Scholar]

- 45.Augustine LF; Nair KM; Rao SF; Rao MV; Ravinder P; Balakrishna N; et al. Adolescent Life-Event Stress in Boys Is Associated with Elevated IL-6 and Hepcidin but Not Hypoferremia. J Am Coll Nutr. 2014;33(5):354–62. 10.1080/07315724.2013.875417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McNamee H, Lloyd K, Schubotz D. Same sex attraction, homophobic bullying and mental health of young people in Northern Ireland. J Youth Stud. 2008;11(1):33–46. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller K, Wakefield J, Sani F. Identification with the school predicts better mental health amongst high school students over time. Educ Child Psychol. 2018;(Special issue):21–9. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Munezawa T, Kaneita Y, Yokoyama E, Suzuki H, Ohida T. Epidemiological study of nightmare and sleep paralysis among Japanese adolescents. Sleep Biol Rhythms. 2009;7(3):201–10. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nakazawa N, Imamura A, Nishida A, Iwanaga R, Kinoshita H, Okazaki Y, et al. Psychotic-like experiences and poor mental health status among Japanese early teens. Acta Med Nagasaki [Internet]. 2011;56(2):35–41. Available from: http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-84858141986&partnerID=tZOtx3y1 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nishida A, Tanii H, Nishimura Y, Kajiki N, Inoue K, Okada M, et al. Associations between psychotic-like experiences and mental health status and other psychopathologies among Japanese early teens. Schizophr Res [Internet]. 2008. February [cited 2018 Apr 26];99(1–3):125–33. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0920996407005610 10.1016/j.schres.2007.11.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nishida A, Sasaki T, Nishimura Y, Tanii H, Hara N, Inoue K, et al. Psychotic-like experiences are associated with suicidal feelings and deliberate self-harm behaviors in adolescents aged 12–15 years. Acta Psychiatr Scand [Internet]. 2010. April [cited 2018 Apr 23];121(4):301–7. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01439.x/full [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nur N. The effect of intimate partner violence on mental health status among women of reproductive ages: A population-based study in a Middle Anatolian city [Internet]. Journal of Interpersonal Violence Sage Publications; November 30, 2012. p. 3236–51. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0886260512441255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ojio Y, Nishida A, Shimodera S, Togo F, Sasaki T. Sleep duration associated with the lowest risk of depression/anxiety in adolescents. Sleep J Sleep Sleep Disord Res. 2016;39(8):1555–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oshima N, Nishida A, Fukushima M, Shimodera S, Kasai K, Okazaki Y, et al. Psychotic-like experiences (PLEs) and mental health status in twin and singleton Japanese high school students. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2010;4(3):206–13. 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2010.00186.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamasaki S, Usami S, Sasaki R, Koike S, Ando S, Kitagawa Y, et al. The association between changes in depression/anxiety and trajectories of psychotic-like experiences over a year in adolescence. Schizophr Res [Internet]. 2018;195:149–53. Available from: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ballbè M, Martínez-Sánchez JM, Gual A, Martínez C, Fu M, Sureda X, et al. Association of second-hand smoke exposure at home with psychological distress in the Spanish adult population. Addict Behav [Internet]. 2015. November [cited 2018 Apr 26];50:84–8. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0306460315002087 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oshima N, Nishida A, Shimodera S, Tochigi M, Ando S, Yamasaki S, et al. The Suicidal Feelings, Self-Injury, and Mobile Phone Use After Lights Out in Adolescents. J Pediatr Psychol [Internet]. 2012. October 1 [cited 2018 Apr 26];37(9):1023–30. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jpepsy/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/jpepsy/jss072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kinoshita Y, Shimodera S, Nishida A, Kinoshita K, Watanabe N, Oshima N, et al. Psychotic-like experiences are associated with violent behavior in adolescents. Schizophr Res [Internet]. 2011. March [cited 2018 Apr 26];126(1–3):245–51. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0920996410014994 10.1016/j.schres.2010.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ando S, Yamasaki S, Shimodera S, Sasaki T, Oshima N, Furukawa TATA, et al. A greater number of somatic pain sites is associated with poor mental health in adolescents: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry [Internet]. 2013. December 17 [cited 2018 Apr 23];13(1):30 Available from: http://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-244X-13-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shiraishi N, Nishida A, Shimodera S, Sasaki T, Oshima N, Watanabe N, et al. Relationship between violent behavior and repeated weight-loss dieting among female adolescents in Japan. PLoS One. 2014;9(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kitagawa Y, Ando S, Yamasaki S, Foo JC, Okazaki Y, Shimodera S, et al. Appetite loss as a potential predictor of suicidal ideation and self-harm in adolescents: A school-based study. Appetite [Internet]. 2017;111:7–11. Available from: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morokuma Y, Endo K, Nishida A, Yamasaki S, Ando S, Morimoto Y, et al. Sex differences in auditory verbal hallucinations in early, middle and late adolescence: Results from a survey of 17 451 Japanese students aged 12–18 years. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Padrón A. Confirmatory factor analysis of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) in spanish adolescents. Qual Life Res. 2012;18(2):197–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Padrón A, Galán I, Rodríguez-Artalejo F. Second-hand smoke exposure and psychological distress in adolescents. A population-based study. Tob Control [Internet]. 2014. July [cited 2018 Apr 26];23(4):302–7. Available from: http://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pisarska A, Ostaszewski K. Medicine use among Warsaw ninth-grade students. Drugs Educ Prev Policy [Internet]. 2011. October 12 [cited 2018 Apr 26];18(5):361–70. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3109/09687637.2010.542786 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rickwood D, D’Espaignet E. Psychological distress among older adolescents and young adults in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 1996;20(1):83–6. 10.1111/j.1467-842x.1996.tb01342.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Basterra V. Prevalence trends of high risk of mental disorders in the Spanish adult population: 2006–2012. Gac Sanit [Internet]. 2017;31(4):324–6. Available from: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2017.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rothon C, Goodwin L, Stansfeld S. Family social support, community “social capital” and adolescents’ mental health and educational outcomes: a longitudinal study in England. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol [Internet]. 2012. May 10 [cited 2018 Apr 26];47(5):697–709. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00127-011-0391-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hale DR, Patalay P, Fitzgerald-Yau N, Hargreaves DS, Bond L, Görzig A, et al. School-Level Variation in Health Outcomes in Adolescence: Analysis of Three Longitudinal Studies in England. Prev Sci. 2014; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rupali R; Mukherjee S; Chaturvedi M; Agarwal K; Kannan A. Prevalence and predictors of psychological distress among school students in Delhi. J Indian Assoc Child Adolesc Ment Heal. 2014;10(November 2009):150–66. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sweeting H, Young R, West P. GHQ increases among Scottish 15 year olds 1987–2006. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol [Internet]. 2009. July 26 [cited 2018 Apr 23];44(7):579–86. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00127-008-0462-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.West P, Sweeting H. Fifteen, female and stressed: Changing patterns of psychological distress over time. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2003;44(3):399–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Young R, Sweeting H. Adolescent Bullying, Relationships, Psychological Well-Being, and Gender-Atypical Behavior: A Gender Diagnosticity Approach. Sex Roles [Internet]. 2004;50(7/8):525–37. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1023/B:SERS.0000023072.53886.86 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sweeting H, West P, Young R. Obesity among Scottish 15 year olds 1987–2006: Prevalence and associations with socio-economic status, well-being and worries about weight. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2008. December 9 [cited 2018 Apr 23];8(1):1–7. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140197101904221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sweeting H, West P, Young R, Der G. Can we explain increases in young people’s psychological distress over time? Soc Sci Med [Internet]. 2010;71(10):1819–30. Available from: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thomson RM, Katikireddi SV. Mental health and the jilted generation: Using age-period-cohort analysis to assess differential trends in young people’s mental health following the Great Recession and austerity in England. Soc Sci Med [Internet]. 2018;214(June):133–43. Available from: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.08.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fagg J, Curtis S, Stansfeld SA, Cattell V, Tupuola A-M, Arephin M. Area social fragmentation, social support for individuals and psychosocial health in young adults: Evidence from a national survey in England. Soc Sci Med [Internet]. 2008. January [cited 2018 Apr 26];66(2):242–54. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0277953607004170 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gotsens M, Malmusi D, Villarroel N, Vives-Cases C, Garcia-Subirats I, Hernando C, et al. Health inequality between immigrants and natives in Spain: The loss of the healthy immigrant effect in times of economic crisis. Eur J Public Health [Internet]. 2015. December [cited 2018 Apr 26];25(6):923–9. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/eurpub/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/eurpub/ckv126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lang IA, Llewellyn DJ, Hubbard RE, Langa KM, Melzer D. Income and the midlife peak in common mental disorder prevalence. Psychol Med [Internet]. 2011. July 10 [cited 2018 Apr 26];41(7):1365–72. Available from: http://www.journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0033291710002060 10.1017/S0033291710002060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Maheswaran H, Kupek E, Petrou S. Self-reported health and socio-economic inequalities in England, 1996–2009: Repeated national cross-sectional study. Soc Sci Med [Internet]. 2015. July [cited 2018 Apr 26];136–137:135–46. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0277953615003081 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pitchforth JM, Viner RM, Hargreaves DS. Trends in mental health and wellbeing among children and young people in the UK: a repeated cross-sectional study, 2000–14. Lancet [Internet]. 2016;388:S93 Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0140673616323297 [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pitchforth J, Fahy K, Ford T, Wolpert M, Viner RM, Hargreaves DS. Mental health and well-being trends among children and young people in the UK, 1995–2014: Analysis of repeated cross-sectional national health surveys. Psychol Med. 2018; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Trainor S, Delfabbro P, Anderson S, Winefield A. Leisure time activities and adolescent psychological well-being. J Adolesc [Internet]. 2010. [cited 2018 Apr 23];33(1):173–86. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0140197109000396 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Trinh L, Wong B, Faulkner GE. The independent and interactive associations of screen time and physical activity on mental health, school connectedness and academic achievement among a population-based sample of youth. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24(1):17–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hamilton HA, Paglia-Boak A, Wekerle C, Danielson AM, Mann RE. Psychological Distress, Service Utilization, and Prescribed Medications among Youth with and without Histories of Involvement with Child Protective Services. Int J Ment Health Addict [Internet]. 2011. August 30 [cited 2018 Apr 26];9(4):398–409. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11469-011-9327-4 [Google Scholar]

- 86.Arbour-Nicitopoulos KP, Faulkner GE, Irving HM. Multiple health-risk behaviour and psychological distress in adolescence. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry [Internet]. 2012. [cited 2018 Apr 23];21(3):171–8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3413466/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Isaranuwatchai W, Rinner C, Hart H, Paglia-Boak A, Mann R, McKenzie K. Spatial Patterns of Drug Use and Mental Health Outcomes Among High School Students in Ontario, Canada. Int J Ment Health Addict [Internet]. 2014. June 16 [cited 2018 Apr 26];12(3):312–20. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11469-013-9455-0 [Google Scholar]

- 88.Van Droogenbroeck F, Spruyt B, Keppens G. Gender differences in mental health problems among adolescents and the role of social support: Results from the Belgian health interview surveys 2008 and 2013. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):1–9. 10.1186/s12888-017-1517-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cheung LM, WONG WS. The effects of insomnia and internet addiction on depression in Hong Kong Chinese adolescents: An exploratory cross-sectional analysis. J Sleep Res [Internet]. 2011 Jun [cited 2018 Apr 23];20(2):311–7. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2010.00883.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yusoff MS. Stress, stressors and coping strategies among secondary school students in a Malaysian government secondary school: Initial findings. ASEAN J Psychiatry. 2010;11(2):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bansal V; Goyal S; Srivastava K. Study of prevalence of depression in adolescent students of a public school. Ind Psychiatry J. 2009;18(1):43 10.4103/0972-6748.57859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Czabała Czes£Aw J.; Brykczyńska Celina; Bobrowski Krzysztof; Ostaszewski K. Mental health problems in the population of high school students in Warsaw. Postêpy Psychiatr i Neurol. 2005;14(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bobrowski KJ; Czabała JC; Brykczyńska C. Risk behaviors as a dimension of mental health assessment in adolescents. Arch Psychiatry Psychother. 2007;1–2:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ahnquist J, Wamala SP, Lindstrom M. Social determinants of health—A question of social or economic capital? Interaction effects of socioeconomic factors on health outcomes. Soc Sci Med [Internet]. 2012. March [cited 2018 Apr 26];74(6):930–9. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0277953612000238 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rocha KB; Pérez K; Rodríguez-Sanz M; Borrell C; Obiols J. Prevalence of mental health problems and its association with socioeconomic, work and health variables: results of the National Health Survey of Spain. Psicothema [Internet]. 2010;22(3):389–95. Available from: http://www.unioviedo.net/reunido/index.php/PST/article/view/8867 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Weich S, Lewis G, Jenkins SP. Income inequality and the prevalence of common mental disorders in Britain. Br J Psychiatry [Internet]. 2001. March 2 [cited 2018 Apr 26];178(03):222–7. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S0007125000156454/type/journal_article [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Okwaraji FE, Obiechina KI, Onyebueke GC, Udegbunam ON, Nnadum GS. Loneliness, life satisfaction and psychological distress among out-of-school adolescents in a Nigerian urban city. Psychol Heal Med [Internet]. 2018;23(9):1106–12. Available from: 10.1080/13548506.2018.1476726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.De Vriendt T, Clays E, Huybrechts I, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Moreno LA, Patterson E, et al. European adolescents’ level of perceived stress is inversely related to their diet quality: The Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence study. Br J Nutr. 2012;108(2):371–80. 10.1017/S0007114511005708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Abu-omar K, Rütten A, Lehtinen V. Mental health and physical activity in the European Union. Soz Praventivmed. 2004;49:301–9. 10.1007/s00038-004-3109-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kedzior KK, Laeber LT. A positive association between anxiety disorders and cannabis use or cannabis use disorders in the general population- a meta-analysis of 31 studies. BMC Psychiatry [Internet]. 2014. December 10 [cited 2018 Apr 26];14(1):136 Available from: http://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-244X-14-136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Young R, Sweeting H. Adolescent Bullying, Relationships, Psychological A Gender Diagnosticity Approach. Sex Roles. 2004; 10.1023/B:SERS.0000037764.40569.2b [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rigby K, Slee PT, Martin G. Implications of inadequate parental bonding and peer victimization for adolescent mental health. J Adolesc. 2007;30(5):801–12. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Glozah FN, Pevalin DJ. Social support, stress, health, and academic success in Ghanaian adolescents: A path analysis. J Adolesc [Internet]. 2014;37(4):451–60. Available from: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Denda K, Kako Y, Kitagawa N, Koyama T. Assessment of depressive symptoms in Japanese school children and adolescents using the birleson depression self-rating scale. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36(2):231–41. 10.2190/3YCX-H0MT-49DK-C61Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ross A, Kelly Y, Sacker A. Time trends in mental well-being: The polarisation of young people’s psychological distress Vol. 52, Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. Ross, Andy: Research Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, ESRC International Centre for Lifecourse Studies in Society and Health, University College London; , 1–19 Torrington Place, London, United Kingdom; 2017. p. 1147–58. 10.1007/s00127-017-1419-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Heim E, Maercker A, Boer D. Value Orientations and Mental Health: A Theoretical Review. Transcult Psychiatry. 2019;56(3):449–70. 10.1177/1363461519832472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.American Psychological Association. Report of the APA Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls. Report of the APA Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/pi/women/programs/girls/report-full.pdf. Washington; 2007.

- 108.Bayliss D, Olsen W, Walthery P. Well-being during recession in the UK Vol. 12, Applied Research in Quality of Life. Springer; 2017. p. 369–87. 10.1007/s11482-016-9465-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Oskrochi G, Bani-Mustafa A, Oskrochi Y. Factors affecting psychological well-being: Evidence from two nationally representative surveys. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Taylor MP, Pevalin DJ, Todd J. The psychological costs of unsustainable housing commitments. Psychol Med [Internet]. 2007. July 16 [cited 2018 Apr 26];37(7):1027–36. Available from: http://www.journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0033291706009767 10.1017/S0033291706009767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Thomas H, Weaver N, Patterson J, Jones P, Bell T, Playle R, et al. Mental health and quality of residential environment. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191(DEC.):500–5. 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.039438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Belfer ML. Child and adolescent mental disorders: The magnitude of the problem across the globe. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2008;49(3):226–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.World Health Organization. Strategic Guidance on Accelerating Actions for Adolescent Health in South-east Asia Region (2018–2022). 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC)

(DOC)

(DOC)

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.