Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the importance of high gradient-amplitude and high slew-rate on oscillating gradient spin echo (OGSE) diffusion imaging for human brain imaging, and to evaluate human brain imaging with OGSE on the MAGNUS head-gradient insert (200 mT/m amplitude and 500 T/m/s slew rate).

Methods

Simulations with cosine-modulated and trapezoidal-cosine OGSE at various gradient amplitudes and slew rates were performed. Six healthy subjects were imaged with the MAGNUS gradient at 3T with OGSE at frequencies up to 100 Hz and b=450 s/mm2. Comparisons were made against standard pulsed gradient spin echo (PGSE) diffusion in-vivo, and in an isotropic diffusion phantom.

Results

Simulations show that to achieve high frequency and b-value simultaneously for OGSE, high gradient amplitude, high slew rates and high peripheral nerve stimulation limits are required. A strong linear trend for increased diffusivity (mean: 8–19%, radial: 9–27%, parallel: 8–15%) was observed in normal white matter with OGSE (20 Hz to 100 Hz) as compared to PGSE. Linear fitting to frequency provided excellent correlation, and using a short-range disorder model provided radial long-term diffusivities of D∞,MD =911±72 μm2/s, D∞,PD =1519±164 μm2/s, and D∞,RD =640±111 μm2/s and correlation lengths of lc,MD =0.802±0.156 μm, lc,PD =0.837±0.172 μm, and lc,RD =0.780±0.174 μm. Diffusivity changes with OGSE frequency were negligible in the phantom, as expected.

Conclusion

The high gradient amplitude, high slew rate, and high peripheral nerve stimulation thresholds of the MAGNUS head-gradient enables OGSE acquisition for in vivo human brain imaging.

Keywords: Diffusion imaging, microstructure, head-gradient

INTRODUCTION

In diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), high amplitude and long (often in tens of milliseconds) gradient waveforms are utilized to generate sufficiently high diffusion-encoding magnetic moments. The performance of the magnetic field gradient sub-system is of critical importance to DWI. Specifically, the diffusion-encoding b-value is proportional to the square of the waveform’s gradient amplitude; also, the rise-time of the waveform is inversely-proportional to the gradient slew rate (SR). Therefore, the ability to generate any given gradient waveform can be constrained by the maximum performance of the gradient sub-system, specifically by its maximum gradient amplitude (Gmax) and its maximum SR (SRmax). In comparison to gradient waveforms utilized by other pulse sequences, DWI is often considered to be the most gradient-power-intensive, since peak current is proportional to Gmax. When used in combination with 2D multi-slice echo-planar imaging (EPI) that employs rapidly-switching trapezoidal readout waveforms, the performance of DW-EPI pulse sequence also has high peak voltage requirements, since peak voltage is proportional to SRmax.

Among the various flavors of diffusivity-encoding gradient waveforms, oscillating gradient spin echo (OGSE)(1–3) is perhaps the most demanding in terms of gradient performance. This is due to the highly oscillatory nature of the OGSE waveforms, i.e., a train of short, high amplitude gradient waveforms, required for encoding selectively high temporal frequencies typically between 50–300 Hz. In comparison, standard, single-pair symmetric trapezoids (also known as pulsed field gradient spin echo or PGSE), twice-refocussed spin echo (4), or even more exotic waveforms like double-diffusion encoding(5,6) and q-space trajectory imaging(7,8) – all excite temporal frequencies with strong 0-Hz components. OGSE waveforms typically have far more +peak to -peak gradient transitions, and hence require both high Gmax and high SRmax. Also, since the first-order magnetic moment is cancelled prior to the refocusing pulse, the achievable OGSE b-values are far smaller than that of PGSE. The benefit of using OGSE is its frequency selectivity, which translates to specific selectivity of microstructural length scales(9,10). OGSE has been applied in preclinical imaging to more accurately characterize tumor cellularity from therapy response(11), length scale changes in restricted-diffusivity in stroke imaging(3), models for demyelinating disease (12) and characterizing hypoxic vs. ischemic injury in traumatic brain injury(13); OGSE has also been applied in in vivo human imaging to characterize spatial restriction of keratin layers in epidermoid cysts(14) (albeit at much larger length scales and lower frequencies).

Despite these advantages, OGSE has primarily been utilized in preclinical MRI, with limited studies in clinical MRI scanners (14–16) due to the required high gradient performance. Preclinical scanners have high Gmax and SRmax, often in excess of 200 mT/m and 500 T/m/s respectively, whereas state-of-the art clinical MRI scanners available commercially are rated at 80 mT/m and 200 T/m/s respectively at writing. Consequently, it is feasible to attain preclinically frequencies of 300 Hz at b=500–1000 s/mm2, whereas the highest frequency for OGSE(15) for clinical MRI systems is 62.5 Hz with b=200 s/mm2. Higher Gmax of 300 mT/m has been demonstrated by the Human Connectome MRI scanner (17), but that system is hardware-limited to a slew rate of 200 T/m/s, and is further limited by whole-body peripheral nerve stimulation (PNS) that severely limits the attainable OGSE frequencies(18). The compact 3T head MRI system(19) has an asymmetric head-sized gradient sub-system of 42-cm inner-diameter (ID) and can reach a very high SR of 700 T/m/s with substantially higher PNS thresholds(20), but is amplitude limited at 80–85 mT/m. Another head-gradient design attains either 100 mT/m and 1200 T/m/s or 200 mT/m and 600 T/m/s (21) but its small ID of 33-cm imposes practical constraints on the use of receiver head coils that are highly beneficial and essential for EPI and DW-EPI.

In this work, OGSE was evaluated on the microstructure anatomy gradient for neuroimaging with ultrafast scanning (MAGNUS)(22), which is a head-gradient that is able to simultaneously achieve high gradient amplitudes and slew rates of Gmax=200 mT/m and SRmax=500 T/m/s respectively with similar high slew rate threshold for PNS as the Compact 3T head gradient(23). The effects of gradient performance on OGSE were first evaluated in simulations to determine the achievable b-values and frequencies. An isotropic diffusion phantom and six healthy subjects were scanned with PGSE and OGSE diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) on the MAGNUS gradient to compare DTI metrics obtained at OGSE frequencies up to 100 Hz and b=450 s/mm2.

METHODS

Oscillating Gradient Waveforms and Spectra

As compared to PGSE, also known as single-spin echo that is typically used in diffusion imaging, OGSE replaces each of the pair of unipolar trapezoidal waveform with sinusoidal waveforms. For pure sinusoidal sine waves with gradient amplitude G, frequency f, and waveform duration τ, the encoding b-value of each waveform is (3) For pure cosine waves, the encoding b-value is about one-third of that of pure sine waves, subject to apodization at the truncated ends of the cosine waveform (3,10). The disadvantage of using sine waveforms is that only one-third of the energy is used in encoding the desired frequency, with most of the energy encoding at f=0 Hz. To increase the encoding b-value, it may be feasible to replace sinusoidal waveforms with alternating trapezoids (15). However, this assumes that the allowable slew rates are sufficiently high that the encoding area of the trapezoid exceeds that of the sinusoid. Also, higher order harmonics would be present in the diffusion spectra.

In simulations, sinusoidal-sine and -cosine waveforms were compared to trapezoidal-sine and cosine-waveforms. The encoding b-value of all waveforms were estimated using the closed form equations above, and then verified by numerical integration with very small adjustments (typically much less than 2%) to the gradient amplitude to calibrate for the desired b-value. In the cosine waveforms, the start and end ramps were not apodized, but the fastest possible ramps (limited either by PNS or by hardware) were calculated and then merged with the trapezoidal waveforms truncated at the ends to the extent that equalizes the gradient moments added by the ramps.

Simulations of Gradient Performance and Peripheral Nerve Stimulation Limits

To determine the trade-offs between frequency and b-value and at various gradient amplitudes G and slew rates SR, a fixed waveform duration of τ=50 ms was assumed. For sinusoidal waveforms (with the exception of the apodized portions of the cosine waveforms), it can be shown that frequency is dependent on the inverse relationship between G and SR, i.e. (see Appendix). With that, the Gmax required could be derived as a function of b and f. This relationship provides the intuition that a high slew rate is required, in addition to high gradient amplitudes. For trapezoidal waveforms of given rise time ξ, the linear PNS equation G = ΔGmin + SRminξ was applied (20), whereby ΔGmin is the minimum gradient amplitude needed to induce PNS, and SRmin is the minimum slew rate needed above ΔGmin to induce PNS. Therefore, the previous inverse relationship between f and SR in sinusoids could not be used in trapezoids. Rather, ξ could be assumed to be that limited by PNS based on the maximum gradient amplitude of the system. Specifically, the PNS parameters used for body gradient were ΔGmin,body = 23.5 mT/m, SRmin,body=70.3 T/m/s, and for MAGNUS head-gradient were ΔGmin,head = 111 mT/m, SRmin,head=145 T/m/s (23) Hence, for each frequency and b-value evaluated with sinusoids, the corresponding b-value for trapezoids could be derived.

The range of simulated frequencies and b-values were 10–350 Hz, and 10–10,000 s/mm2 respectively, which adequately encompassed the current and forseeable Gmax and SRmax capabilities of body and head gradients.

Microstructure Model for OGSE

DTI metrics such as mean diffusivity (MD), radial diffusivity (RD), parallel diffusivity (PD) and fractional anisotropy (FA) can be computed from DTI-based OGSE acquisition. In addition, frequency-dependent metrics provide differentiating, length-scale specific microstructure characteristics. It had been suggested that fitting the OGSE signal against frequency might be used as such a differentiator (11). Novikov (24), Fieremans (25), and Burcaw (26) proposed a disorder model that incorporates formulations for frequency effects that might provide a more empirically-useful depiction of white matter diffusivity; the premise was that clinical MRI gradients were primarily sensitive to structures of about 10 μm sizes, which would be inadequate for interrogating the intra-axonal water of white matter axons that have diameters on the order of 1 μm (27). Hence, conventional MRI gradients should be more sensitive to extra-axonal water rather than intra-axonal water; this observation had been corrobated by De Santis, et al.(28)

Following equation 2 in Burcaw, et al. (26) that describes short-range disorder for radial axonal diffusivity, the measured diffusivity could be approximated by

| (1) |

where ω=2πf, and , where lc is the correlation length of a two-dimensional, disordered packing geometry, and A is an amplitude parameter that had been determined to be empirically related to lc and is the slope in this linear relationship. D∞ is defined as long range diffusivity and is the intercept. The slope dD/df has also been defined as the diffusion dispersion rate (DDR) (29,30)and is related to lc by DDR .

Human Subject and Phantom Imaging

In accordance with an IRB-approved protocol, six healthy subjects (4M, 2F, age=32–59 years) were recruited and imaged on the MAGNUS gradient (Gmax=200 mT/m, SRmax=500 T/m/s per-axis) installed on a 3T MRI Scanner (Signa MR750, General Electric Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) with its whole-body gradient and RF coil removed. A custom 37-cm inner-diameter RF transmit/receiver coil was used for transmit with a 32-channel phased-array brain coil receiver (Nova Medical, Wilmington, MA USA). A spin-echo diffusion-EPI sequence was modified to enable arbitrary diffusion encoding waveforms such as OGSE. In this work, the duration of the diffusion encoding waveforms before and after refocusing pulse was each limited to about 50 ms. Exemplary OGSE waveforms are shown in Fig. 1a–f. For corresponding PGSE experiments, Stejskal-Tanner diffusion encoding gradients of about 50 ms duration (mixing time of 11.1 ms, pulse width of 4.1 ms) were used and the amplitude was scaled to match the b-value of the OGSE experiments.

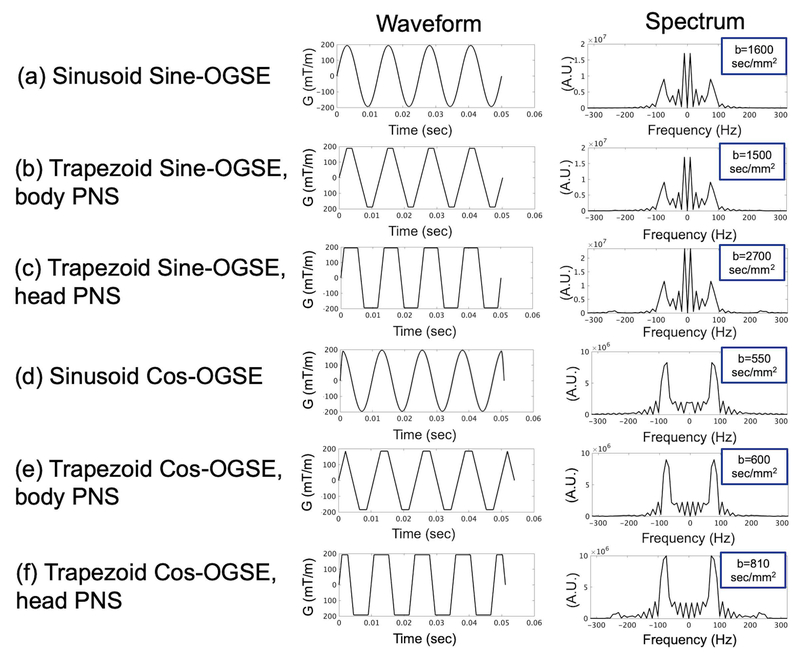

Figure 1.

Waveforms and spectra for 80-Hz (a-c) sine-OGSE and (d-f) cosine-OGSE, with (a,d) sinusoidal or (b,c,e,f) trapezoidal modulation (with ramps constrained by either (b,e) whole-body or (c,f) head-only gradient PNS), and the resulting maximum b-values, assuming a nominal maximum gradient amplitude of 200 mT/m and maximum waveform duration of 50 ms (half of the symmetric pair of diffusion-encoding waveforms is shown). In (d), the ascending and descending ramps of sinusoidal cosine-OGSE assume head-only PNS.

Each subject was scanned with standard PGSE DTI with one b=0 s/mm2 and twenty b=450 s/mm2 directions, as well as with OGSE DTI with one b=0 s/mm2 and twenty b=450 s/mm2 directions per frequency at five frequencies (20, 40 60, 80 and 100 Hz) for a total of 20 directions per frequency. The same DTI directions were used for all frequencies. The other image acquisition parameters were kept constant (TR/TE=7000/122 ms, FOV=25.6 cm, 128×128 matrix, slice thickness=3 mm, 42 slices, no slice gap, echo spacing=428 μs, no parallel imaging). The detailed parameters are listed in Supporting Information Table S1, and the waveform and spectra for each frequency are shown in Figure S1.

To determine the effects of reducing the number of directions or reducing signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) from parallel imaging (with the benefit of reduced distortion), two additional scans were acquired in two subjects (male 42 years-old and male 41 years-old). In the first additional scan, an OGSE with 12 directions per frequency with no parallel imaging was acquired, and in the second additional scan an OGSE also with 12 directions but in-plane parallel imaging factor of two. The total scan times for OGSE were 12 minutes (20 directions) and 7.4 minutes (12 directions). A spherical phantom (11-cm diameter) with 20% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) with a nominal mean diffusivity of about 1350 μm2/s at room temperature was also imaged with each sequence. The phantom was placed at iso-center for thirty minutes prior to scan to reduce possible effects from thermal conduction and residual motion.

Image Analysis

For each set of DTI acquisitions, MD, RD, PD and FA maps were calculated. On the MAGNUS head-only scanner, it was required to also perform gradient nonlinearity correction (31) due to the increased nonlinearity effects on the head-gradient (32). The OGSE DTI maps were obtained on a per frequency basis (with the b=0 image shared between the five frequencies).

For analysis, the FA atlas (John Hopkin’s ICBM DTI-81) with 50 parcellated white matter (WM) regions was co-registered with MNI_ICBM152_2009a atlas using an in-house implementation(33) and ANTs(34). The individual subject FA maps were then non-rigidly registered to the FA atlas using the ANTs Symmetric Normalization (SyN) method(35,36), for automating labeling of WM parcels in the subject. The mean and standard deviation of the all the diffusion maps within each of these parcels were obtained. Supporting Information Table S2 lists the 50 parcels. In addition, linear fitting of OGSE metrics using the disordered model (Eqn.[1]) was performed based on the mean values for each parcel. Wilcoxon signed rank-test was used to determine if metrics for each parcel were different (p<0.05 indicates statistical significance). In addition, for visualization the MD, RD and PD maps were fitted linearly to the short-range disorder model of Eqn.[1] on a per-pixel basis. In the phantom, the diffusivity metrics were measured in a central rectangular region of interest of area about 15 cm2.

To evaluate the effects of decreasing the number of diffusion directions and increasing parallel imaging factor, paired t-test using the means from the 50 WM parcels from the two subjects was used. The coefficient of variation (CoV), based on standard deviation of each parcel for each subject, was also compared using paired t-test. Finally, the parameters for OGSE disordered models were also compared.

In addition, gray matter (GM) parcels from an atlas (37) also defined in MNI space were analyzed. The 116 GM parcels from the atlas were grouped into 7 parcels to prevent poor fitting over small regions of interests. These parcels are also listed in Supporting Information Table S2.

RESULTS

Simulations of Gradient Performance and Peripheral Nerve Stimulation Limits

Fig.1 compares example waveforms for the various OGSE methods analyzed in simulation and their respective spectra at 80 Hz. The spectra were computed by taking into account both waveforms about a 7 ms refocusing pulse width that has been suggested to depict the acquisition more accurately (16). A nominal 50 ms per waveform duration was used to determine the maximum allowable b-value. Pure sinusoidal sine-OGSE (Fig.1a) had a higher b-value than pure sinusoidal cosine-OGSE (Fig.1d) by a factor of about three, as mentioned before. However, there was a strong f=0 Hz component in sinusoidal sine that was about 2–3 times the amplitude of the 80 Hz peaks. In the pure cosine-OGSE, the 0 Hz component was reduced to about 25% the amplitude of the 80 Hz peaks, which were residual from the truncated ends and the finite duration of the refocusing pulse width. The amplitudes of the 80 Hz peak were approximately the same in sine- and cosine-OGSE. Body-PNS-limited trapezoidal sine-OGSE (Fig.1b) replaced sinusoidal ramps with straight ramps constrained by PNS (2.5 ms duration for zero-to-200 mT/m peak amplitude). However, due to body-PNS-limited trapezoidal ramps, the b-values were not very different from than that obtained from pure sinusoids. Head-PNS-limited trapezoidal sine-OGSE (Fig.1c) had much faster ramps (0.9 ms for zero-to-200 mT/m peak amplitude) that resulted in higher b-values by about double, while its cosine-OGSE (Fig.1f) increased b-value by about 45%. The 80 Hz peaks were quite similar in the trapezoidal waveforms, except for very small (~10%) but noticeable 160 Hz harmonics in the head-PNS trapezoids.

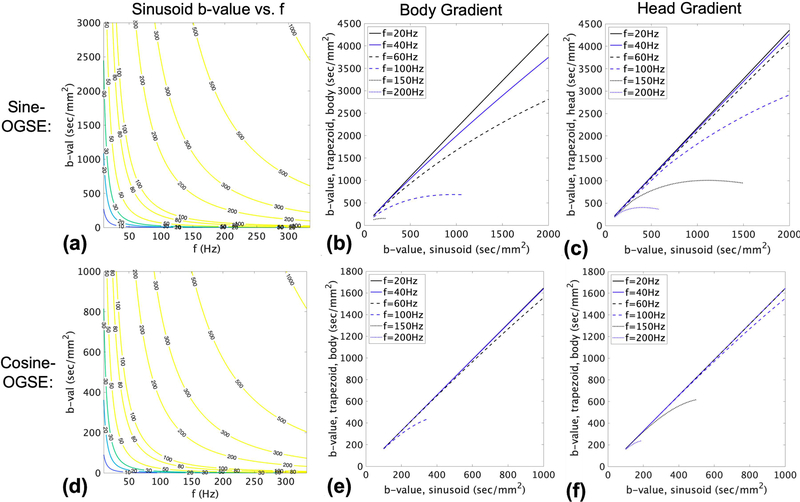

The simulation results of Fig.2a,d show the required Gmax for the array of b-values and frequencies at a nominal waveform duration of 50 ms, showing the trade-off between b-value and frequency for the same Gmax. At Gmax=200 mT/m for MAGNUS, 100 Hz sinusoidal-OGSE provides b=1000 s/mm2and doubling frequency reduces b-value by about factor of four. Going from sine to cosine reduces b-value by a factor of three, as predicted by the closed form expressions. Fig. 2b,e show that higher b-values could be obtained with trapezdoial OGSE with body-PNS-limited ramps, but primarily at lower frequencies (up to about 60 Hz). As frequency increased, the b-value benefits of trapezoidal waveforms over sinusoidal waveforms are reduced and diminish at higher b-values. With head-PNS-limited ramps, much higher b-values could be obtained and at a wider range of frequencies, up to about 150 Hz.

Figure 2.

Achievable sine-OGSE (a-c) and cosine-OGSE (e-f) frequencies and b-values based on gradient performance. (a,d) The minimum required gradient amplitude (in mT/m) for sinusoid sine-OGSE for a waveform duration of 50 ms; (b,e) maximum b-value of trapezoid-modulated OGSE vs. b-value of sinusoidal OGSE at the same gradient amplitude for whole-body gradient performance and PNS; (c,f) maximum b-value of trapezoid-modulated sine-OGSE vs. b-value of sinusoidal OGSE at the same gradient ampltidue for head-only gradient performance and PNS.

Imaging – OGSE vs. PGSE

In the static phantom, the PGSE metrics (20 directions) were MD=1361±20 μm2/s, RD=1339±20 μm2/s, PD=1405±24 μm2/s, FA=0.0333±0.0056. In comparison, OGSE metrics resulted in mildly higher diffusivity values and higher FA (MD: +0.4 to +1.5%, RD: +0.5 to +1.1%, PD: +0.2 to +2.8%, FA:−9.3 to +35.4%).

Table 1 summarizes the in vivo human results from all 50 WM parcels and the 7 GM parcels. Overall for WM, OGSE diffusivity measures were higher than that from PGSE, and the increase was approximately linear; at 100 Hz OGSE, the increase over PGSE were 19% (MD), 27% (RD), and 15% (PD), much higher than that seen in the phantom. The number of WM parcels with statistically significant differences also increased with OGSE frequency. As expected, FA decreased, by −8%. In GM, a similar linear trend was observed, but the increase was more isotropic – 20% in MD, PD and RD; FA changes were neglible.

Table 1.

Results of PGSE vs. OGSE metrics, showing mean (and standard deviation) across all subjects (n=6) and parcels (50 WM, 7 GM), the mean percentage increase at each OGSE frequency over PGSE, and the number of parcels (out of 50 or 7) with statistically-significant increase or decrease.

| Metric | PGSE Mean (Std. Dev.) | %(OGSE-PGSE), and Number of WM Parcels (upon 50) with Significant Increase/Decrease for Each OGSE Frequency | |||||||||

| 20 Hz | 40 Hz | 60 Hz | 80 Hz | 100 Hz | |||||||

| MD (μm2/s) | 884.7 (135.4) | 7.77% | 27/0 | 10.85% | 33/0 | 13.44% | 36/0 | 16.20% | 36/0 | 19.21% | 36/0 |

| PD (μm2/s) | 1516.4 (265.2) | 8.10% | 35/0 | 9.63% | 40/1 | 10.66% | 38/0 | 12.36% | 38/1 | 15.17% | 40/1 |

| RD (μm2/s) | 624.7 (127.4) | 9.41% | 32/1 | 14.24% | 39/1 | 18.61% | 40/0 | 22.33% | 41/0 | 26.88% | 43/0 |

| FA | 0.544 (0.074) | −0.80% | 0/2 | −3.28% | 0/14 | −5.62% | 0/29 | −6.99% | 0/35 | −8.21% | 0/37 |

| Metric | PGSE Mean (Std. Dev.) | %(OGSE-PGSE), and Number of GM Parcels (upon 7) with Significant Increase/Decrease for Each OGSE Frequency | |||||||||

| 20 Hz | 40 Hz | 60 Hz | 80 Hz | 100 Hz | |||||||

| MD (μm2/s) | 1020.3 (51.0) | 8.60% | 7/0 | 12.34% | 7/0 | 14.58% | 7/0 | 17.28% | 7/0 | 20.07% | 7/0 |

| PD (μm2/s) | 1323.4 (78.9) | 8.87% | 7/0 | 11.71% | 7/0 | 12.99% | 7/0 | 15.91% | 7/0 | 19.76% | 7/0 |

| RD (μm2/s) | 897.3 (51.9) | 8.53% | 7/0 | 12.64% | 7/0 | 15.31% | 7/0 | 17.67% | 7/0 | 19.59% | 7/0 |

| FA | 0.210 (0.023) | 6.01% | 1/0 | 2.34% | 0/0 | −3.06% | 0/1 | −2.49% | 1/1 | 1.13% | 1/2 |

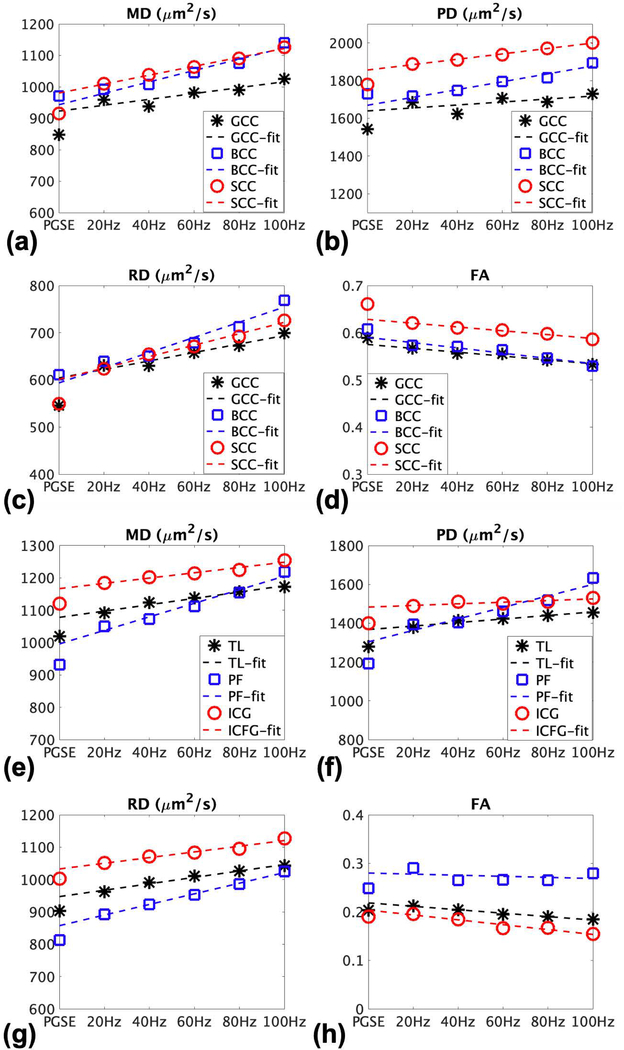

Fig. 3a–d shows diffusivity plots for three WM parcels (in the corpus callosum) from the same subject. Good linear correlation could be observed in the MD, PD and RD plots (a-c), showing increase in diffusivity going from PGSE to higher OGSE frequencies. Majority of the parcels had good linear correlation (mean R2 values across all subjects and parcels were 0.87, 0.77, 0.88 for MD, PD and RD respectively). Similarly, the decrease in FA could also be observed (Fig. 3d) with good linear correlation. Supporting Information Tables S3, S4, S5 and S6 provide further detailed results for all subjects and for each white matter parcel for MD, PD, RD and FA respectively.

Figure 3.

Plots of DTI metrics for three white matter parcels (genu, body, and splenium of the corpus callosum) and three gray matter parcels (temporal lobes, posterior fossa, insula/cingulate gyri) for PGSE and various OGSE frequencies from a subject (male, 59 years), showing the general trend in the majority of the parcels of increased (a,e) mean diffusivity, (b,f) parallel diffusivity, (c,g) radial diffusivity, but decreased (d,h) fractional anisotropy going from PGSE to OGSE, and with higher OGSE frequency.

Fig. 3e–f show the similar plots for three GM parcels. The linear correlation was excellent in MD, PD and RD in every parcel (R2 between 0.90 and 0.99), except in the posterior fossa (PF), where R2 was 0.75 and 0.58 in MD and RD respectively averaged across all subjects. Supporting Information Table S7 provides further detailed results.

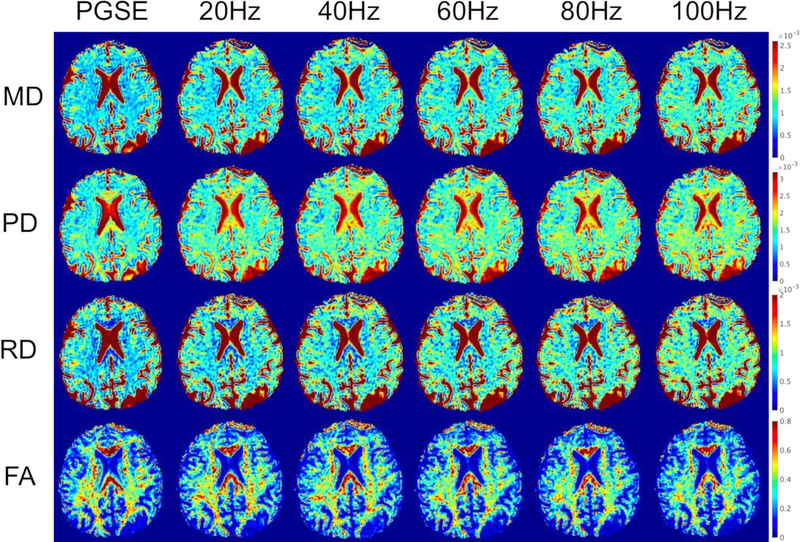

Fig.4 shows exemplary diffusivity maps from one subject. The increase in MD, PD and RD, as well as the decrease in FA could be observed in these maps going from PGSE to higher OGSE frequencies.

Figure 4.

Representative DTI maps from a subject (male, 59 years) of mean diffusivity (MD), parallel diffusivity (PD), radial diffusivity (RD) and fractional anisotropy (FA) from PGSE and the various OGSE frequencies (20 Hz to 100 Hz), demonstrating visible increase in diffusivity measures and decrease in FA from PGSE to OGSE and with higher OGSE frequency.

Application of Disordered Model for Microstructure Imaging

Tables 2 and 3, show the long-term diffusivity D∞ and correlation length lc values respectively. These were obtained by fitting the mean values for MD, PD and RD for every white matter parcel. For any subject-parcel with poor fitting (with low correlation of R2<0.85) the parcel was excluded from the analysis to maintain the same number of subjects in all results (N=6), as were results with negative lc2. In other words, all fitted results that were reported in Tables 2 and 3 had R2≥0.85 in every subject. Out of 50 WM parcels, majority of remaining parcels had good linear correlation and valid lc – 41 for MD, 30 for PD and 43 for RD. The mean (± standard deviation) values for long-term diffusivity for WM were D∞,MD =911±72 μm2/s, D∞,PD =1519±164 μm2/s, and D∞,RD =640±111 μm2/s. The values for correlation lengthin WM were lc,MD =0.802±0.156 μm, lc,PD =0.837±0.172 μm, and lc,RD =0.780±0.174 μm. Accordingly, the mean values for diffusion dispersion rate (DDR) were DDRMD=0.681 μm2, DDRPD=0.719 μm2 and DDRRD=0.662 μm2 (mean values for each parcel are shown in Supporting Information Table S8). The D∞ values could not be differentiated statistically from their respective PGSE diffusivities (of Table 1), but were slightly larger on average. The lc,PD was slightly larger than lc,RD and was not statistically significantly different.

Table 2.

Long-term diffusivity (in μm2/s, n=6) for the mean, parallel and radial diffusivity maps (MD, PD and RD respectively), with mean (and standard deviation) shown per white matter or gray matter (GM) parcel. Blanked entries reflect results with poor fitting (with any one subject having R2<0.85).

| Parcel | MD | PD | RD |

|---|---|---|---|

| MCP | 1140.9(259.1) | -(-) | 914.0(222.9) |

| PCT | 994.6(188.2) | 1633.4(583.9) | 782.9(131.9) |

| GCC | 918.4(38.6) | -(-) | 591.5(49.6) |

| BCC | 904.9(31.7) | 1693.8(52.2) | 526.5(57.8) |

| SCC | 879.6(53.9) | 1807.9(53.0) | 500.3(53.9) |

| FX | -(-) | -(-) | 1119.6(216.7) |

| CST-R | -(-) | -(-) | -(-) |

| CST-L | 981.9(213.0) | -(-) | -(-) |

| ML-R | 858.6(196.5) | -(-) | 586.4(202.7) |

| ML-L | 871.2(205.9) | -(-) | 614.5(229.5) |

| ICP-R | 920.8(206.9) | 1783.9(797.7) | 688.9(278.1) |

| ICP-L | 869.4(296.2) | 1792.7(920.4) | 652.2(251.4) |

| SCP-R | 894.4(99.7) | -(-) | 484.5(81.7) |

| SCP-L | 814.3(50.1) | -(-) | 442.4(57.3) |

| CP-R | -(-) | -(-) | -(-) |

| CP-L | -(-) | -(-) | -(-) |

| ALIC-R | 820.0(38.7) | 1521.9(28.6) | 545.5(34.6) |

| ALIC-L | 839.0(50.9) | 1546.1(106.2) | 568.7(48.1) |

| PLIC-R | 841.4(11.3) | 1606.2(43.9) | 481.3(23.3) |

| PLIC-L | 840.0(12.1) | 1609.5(59.7) | 497.0(18.6) |

| RLIC-R | 903.8(33.2) | 1562.7(14.8) | 585.5(50.1) |

| RLIC-L | 931.8(29.4) | 1605.6(73.9) | 603.4(30.8) |

| ACR-R | 879.1(42.6) | 1297.8(39.1) | 672.8(54.8) |

| ACR-L | 877.6(43.1) | 1277.4(37.5) | 683.2(50.8) |

| SCR-R | 850.3(40.5) | 1334.9(41.3) | 609.6(46.5) |

| SCR-L | 851.7(33.6) | 1332.1(40.8) | 612.8(39.2) |

| PCR-R | 954.4(60.9) | 1451.7(55.2) | 709.0(67.1) |

| PCR-L | 945.5(45.0) | 1438.1(38.9) | 702.2(50.6) |

| PTR-R | 935.7(52.2) | 1615.6(39.3) | 618.0(58.5) |

| PTR-L | 972.1(47.7) | 1620.6(11.7) | 666.6(67.3) |

| SS-R | 958.3(53.8) | 1611.7(59.6) | 642.4(57.4) |

| SS-L | 960.7(57.8) | 1608.6(69.1) | 650.3(49.1) |

| EC-R | 879.0(27.3) | 1310.5(30.5) | 666.4(31.8) |

| EC-L | 884.2(32.5) | 1329.9(33.0) | 668.6(39.0) |

| CGC-R | 898.8(20.9) | 1389.3(22.0) | 662.1(34.0) |

| CGC-L | 921.5(20.6) | -(-) | 671.2(36.0) |

| CGH-R | -(-) | -(-) | 631.1(74.6) |

| CGH-L | 862.2(87.9) | -(-) | 645.2(66.2) |

| FX/ST-R | 934.6(57.1) | 1623.7(94.2) | 621.1(46.3) |

| FX/ST-L | -(-) | -(-) | 639.4(90.6) |

| SLF-R | 884.4(44.5) | 1347.3(37.1) | 654.6(49.3) |

| SLF-L | 888.9(43.5) | 1340.0(34.3) | 666.1(54.3) |

| SFO-R | -(-) | -(-) | 601.3(57.8) |

| SFO-L | 831.0(59.2) | 1325.7(55.3) | 608.8(44.4) |

| IFO-R | -(-) | -(-) | -(-) |

| IFO-L | 906.5(28.5) | -(-) | 654.5(27.9) |

| UNC-R | 905.1(118.3) | 1416.3(135.6) | 653.5(111.8) |

| UNC-L | -(-) | -(-) | -(-) |

| TAP-R | 995.5(119.2) | -(-) | 703.9(95.9) |

| TAP-L | 1155.0(133.4) | -(-) | -(-) |

| TL (GM) | 1018.4(42.8) | 1287.0(68.1) | 896.3(37.4) |

| PF (GM) | -(-) | 1343.1(207.5) | -(-) |

| ICG (GM) | 1024.4(75.1) | 1313.3(91.4) | 893.2(74.1) |

| FL (GM) | 1133.6(163.4) | 1458.9(180.8) | 1005.4(160.8) |

| OL (GM) | 1028.4(74.4) | 1358.6(116.8) | 890.2(71.7) |

| PL (GM) | 1186.6(151.3) | 1567.4(251.7) | 1057.3(153.8) |

| CS (GM) | 1133.1(116.0) | 1503.6(184.3) | 1002.6(113.6) |

Table 3.

Correlation length (in μm, n=6) for the mean, parallel and radial diffusivity maps (MD, PD and RD respectively), with mean (and standard deviation) shown per white matter or gray matter (GM) parcel. Blanked entries reflect results with poor fitting (with any one subject having R2<0.85).

| Parcel | MD | PD | RD |

|---|---|---|---|

| MCP | 0.401(0.445) | -(-) | 0.197(0.305) |

| PCT | 0.513(0.504) | 0.723(0.914) | 0.417(0.362) |

| GCC | 0.739(0.084) | -(-) | 0.686(0.077) |

| BCC | 0.994(0.055) | 0.989(0.080) | 0.976(0.065) |

| SCC | 0.833(0.064) | 0.795(0.130) | 0.764(0.065) |

| FX | -(-) | -(-) | 0.532(0.469) |

| CST-R | -(-) | -(-) | -(-) |

| CST-L | 0.773(0.426) | -(-) | -(-) |

| ML-R | 0.679(0.586) | 0.752(0.831) | 0.650(0.534) |

| ML-L | 0.635(0.560) | -(-) | 0.627(0.513) |

| ICP-R | 0.791(0.624) | 0.967(0.935) | 0.736(0.572) |

| ICP-L | 0.832(0.665) | 1.011(0.821) | 0.799(0.465) |

| SCP-R | 0.632(0.643) | -(-) | 0.821(0.421) |

| SCP-L | 0.935(0.377) | -(-) | 0.939(0.292) |

| CP-R | -(-) | -(-) | -(-) |

| CP-L | -(-) | -(-) | -(-) |

| ALIC-R | 0.820(0.130) | 0.732(0.272) | 0.805(0.084) |

| ALIC-L | 0.740(0.083) | 0.600(0.306) | 0.685(0.077) |

| PLIC-R | 1.053(0.128) | 0.986(0.128) | 1.072(0.142) |

| PLIC-L | 1.077(0.098) | 0.997(0.118) | 1.082(0.086) |

| RLIC-R | 0.809(0.074) | 0.778(0.091) | 0.814(0.086) |

| RLIC-L | 0.872(0.108) | 0.895(0.121) | 0.849(0.124) |

| ACR-R | 0.817(0.106) | 0.828(0.130) | 0.810(0.092) |

| ACR-L | 0.781(0.096) | 0.763(0.115) | 0.782(0.091) |

| SCR-R | 1.066(0.081) | 1.042(0.074) | 1.075(0.089) |

| SCR-L | 1.044(0.103) | 1.017(0.092) | 1.055(0.109) |

| PCR-R | 0.947(0.065) | 0.960(0.079) | 0.934(0.062) |

| PCR-L | 0.950(0.085) | 0.972(0.110) | 0.933(0.082) |

| PTR-R | 0.841(0.109) | 0.846(0.134) | 0.828(0.108) |

| PTR-L | 0.835(0.078) | 0.882(0.098) | 0.799(0.083) |

| SS-R | 0.830(0.118) | 0.864(0.162) | 0.793(0.132) |

| SS-L | 0.812(0.074) | 0.829(0.142) | 0.790(0.063) |

| EC-R | 0.815(0.083) | 0.781(0.079) | 0.829(0.087) |

| EC-L | 0.788(0.055) | 0.740(0.039) | 0.802(0.066) |

| CGC-R | 0.787(0.104) | 0.739(0.192) | 0.794(0.073) |

| CGC-L | 0.810(0.120) | -(-) | 0.810(0.092) |

| CGH-R | -(-) | -(-) | 0.579(0.276) |

| CGH-L | 0.554(0.299) | -(-) | 0.627(0.197) |

| FX/ST-R | 0.634(0.228) | 0.338(0.392) | 0.718(0.190) |

| FX/ST-L | -(-) | -(-) | 0.701(0.146) |

| SLF-R | 0.983(0.061) | 1.018(0.067) | 0.962(0.057) |

| SLF-L | 0.983(0.104) | 1.032(0.102) | 0.954(0.107) |

| SFO-R | -(-) | -(-) | 0.838(0.121) |

| SFO-L | 0.823(0.108) | 0.836(0.085) | 0.769(0.214) |

| IFO-R | -(-) | -(-) | -(-) |

| IFO-L | 0.554(0.085) | -(-) | 0.572(0.125) |

| UNC-R | 0.587(0.179) | 0.406(0.371) | 0.620(0.210) |

| UNC-L | -(-) | -(-) | -(-) |

| TAP-R | 0.807(0.197) | -(-) | 0.719(0.271) |

| TAP-L | 0.713(0.188) | -(-) | -(-) |

| TL (GM) | 0.733(0.090) | 0.772(0.112) | 0.695(0.115) |

| PF (GM) | -(-) | 1.377(0.535) | -(-) |

| ICG (GM) | 0.791(0.114) | 0.708(0.157) | 0.799(0.113) |

| FL (GM) | 0.809(0.175) | 0.720(0.214) | 0.816(0.163) |

| OL (GM) | 0.852(0.103) | 0.883(0.150) | 0.809(0.099) |

| PL (GM) | 0.835(0.144) | 0.777(0.200) | 0.827(0.107) |

| CS (GM) | 0.850(0.126) | 0.866(0.149) | 0.802(0.155) |

The GM results (Tables 2 and 3) were D∞,MD =1084±67 μm2/s, D∞,PD =1405±106 μm2/s, and D∞,RD =957±67 μm2/s. The values for correlation length in WM were lc,MD =0.823±0.051 μm, lc,PD =0.872±0.233 μm, and lc,RD =0.757±0.102 μm. Accordingly, the mean values for diffusion dispersion rate (DDR) were DDRMD=0.701 μm2, DDRPD=0.849 μm2 and DDRRD=0.599 μm2 (mean values for each parcel are shown in Table S8).

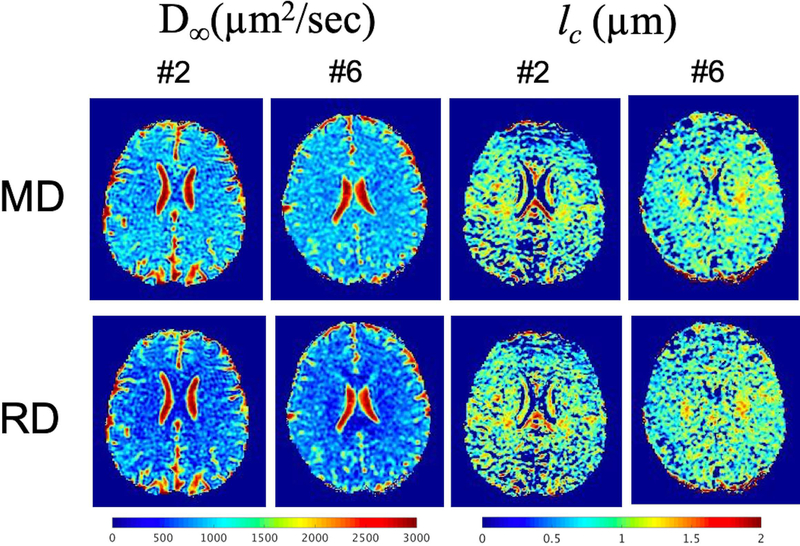

Fig. 5 shows D∞ and lc MD and RD maps in two subjects. In comparison to the results from Tables 2 and 3, the fit was performed on a per-voxel rather than on a per-parcel basis. As before, voxels with negative lc2 were masked from display. While the fitted D∞ maps were in approximate ranges as compared to the fitted parcel results, there were many lc pixels that were severely underestimated due to fitting to noise on a per-voxel basis. The PD maps were more prone to poor linear fitting, and the results were not shown.

Figure 5.

Representative maps of long-term diffusivity (D∞) and correlation length (lc) obtained from mean and radial diffusivity (MD, RD respectively) using the disordered model from two subjects (male, 41 years-old) and (female, 32 years-old).

Imaging – Optimization for Imaging Parameters

Table 4 summarizes the effects from reducing the number of diffusion directions, and from parallel imaging factor of two. In the former, scan time was reduced by about 40%, at the cost of reduced ability to improve diffusion contrast and anisotropy differentiation; in the latter, SNR would be reduced but image distortion improved. Reducing the number of directions had a small but significant effect on increasing PD (+1.3%), the effects of which increased with OGSE frequency (+4.8% at 100 Hz). This was also a significant effect in MD (+4.4% at 100 Hz). The CoV was significantly decreased in MD (−14.1 to −17.2%); CoV was also decreased in OGSE RD (−6.3 to 8.1%), but not in PGSE RD. The D∞,PD had a small significant increase (+2.4%), while D∞,RD had a small significant decrease (−2.4%). The lc,MD and lc,RD both had significant increase (+9.9% and +8.0% respectively).

Table 4.

Results of comparisons between different acquisition parameters for PGSE and OGSE, on percentage difference in the mean of the metric, difference in coefficient of variation (CoV), and on the parameters from the disordered model. In the top half, the results are for the number of diffusion directions was decreased from 20 to 12. In the bottom half, parallel imaging factor R=2 was compared against no parallel imaging.

| % Difference in Mean (12-directions vs. 20-directions) | % Difference in CoV (12-directions vs. 20-directions) | % Difference (12-direction vs. 20-directions) | ||||||||||||

| PGSE | 20Hz | 40Hz | 60Hz | 80Hz | 100Hz | PGSE | 20Hz | 40Hz | 60Hz | 80Hz | 100Hz | OGSE D∞ | OGSE lc | |

| MD | 0.67 (0.405) |

1.98 (0.019) |

2.96 (<0.001) |

4.23 (<0.001) |

4.12 (<0.001) |

4.43 (<0.001) |

−1.26 (0.474) |

−14.09 (<0.001) |

−15.11 (<0.001) |

−17.16 (<0.001) |

−15.25 (<0.001) |

−15.59 (<0.001) |

0.82 (0.209) |

9.86 (<0.001) |

| PD | 1.28 (0.004) |

3.49 (<0.001) |

3.96 (<0.001) |

4.98 (<0.001) |

4.95 (<0.001) |

4.81 (<0.001) |

2.03 (0.113) |

0.20 (0.908) |

0.83 (0.522) |

−2.09 (0.085) |

−0.17 (0.893) |

−1.06 (0.378) |

2.42 (<0.001) |

8.06 (0.086) |

| RD | −0.05 (0.934) |

−1.69 (0.017) |

−0.87 (0.246) |

0.13 (0.842) |

0.62 (0.366) |

0.53 (0.445) |

−1.48 (0.198) |

−6.33 (<0.001) |

−7.23 (<0.001) |

−8.12 (<0.001) |

−7.43 (<0.001) |

−7.99 (<0.001) |

−2.36 (0.004) |

7.99 (0.025) |

| % Difference in Mean (R=2 vs. R=1) | % Difference in CoV (R=2 vs. R=1) | % Difference (R=2 vs. R=1) | ||||||||||||

| PGSE | 20Hz | 40Hz | 60Hz | 80Hz | 100Hz | PGSE | 20Hz | 40Hz | 60Hz | 80Hz | 100Hz | OGSE D∞ | OGSE lc | |

| MD | 0.54 (0.795) |

0.27 (0.882) |

0.51 (0.779) |

−0.66 (0.684) |

−1.77 (0.227) |

−1.90 (0.237) |

13.91 (<0.001) |

5.31 (0.028) |

4.27 (0.071) |

5.09 (0.037) |

6.44 (0.008) |

7.16 (0.006) |

−1.36 (0.085) |

−2.76 (0.265) |

| PD | 6.60 (0.001) |

4.61 (0.007) |

4.78 (0.008) |

4.48 (0.006) |

3.83 (0.015) |

4.09 (0.007) |

8.54 (<0.001) |

10.11 (<0.001) |

9.71 (<0.001) |

11.09 (<0.001) |

11.16 (<0.001) |

9.50 (<0.001) |

2.32 (<0.001) |

4.47 (0.258) |

| RD | 4.17 (0.064) |

−2.35 (0.295) |

−3.40 (0.123) |

−4.46 (0.024) |

−5.38 (0.001) |

−5.10 (0.006) |

2.99 (0.137) |

3.17 (0.062) |

4.01 (0.033) |

4.45 (0.019) |

6.55 (0.001) |

6.72 (<0.001) |

−3.47 (0.001) |

−6.24 (0.012) |

Parallel imaging factor of two on the other hand resulted in different effects. PD increased in PGSE (+6.6%) and also in OGSE (+3.8 to +4.8%). RD was reduced at 80–100 Hz (−4.5 to −5.4%). The CoV was increased in almost every metric and PGSE/OGSE frequency (by +4.0 to 13.9%). The D∞,PD had a small significant increase (+2.3%), while D∞,RD had a small significant decrease (−3.5%). The lc,RD had a significant decrease (−6.2%).

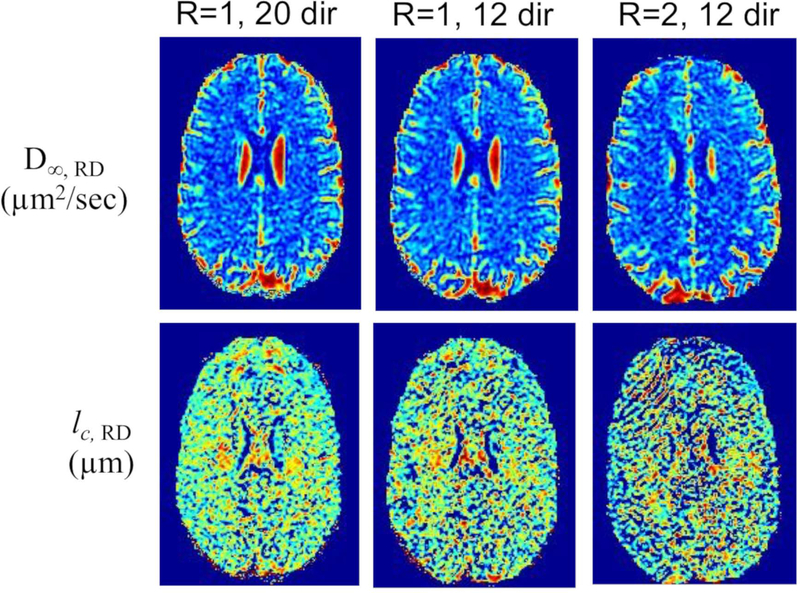

Fig. 6 compares disordered metrics for RD in one subject which had the three scans at the different imaging parameters. Qualitatively, the D∞,RD maps look very similar. The lc,RD maps were visibly noisier with parallel imaging R=2.

Figure 6.

OGSE maps of radial diffusivity (long-term diffusivity and correlation length) obtained with different pulse sequence optimization parameters for another subject (male, 42 years-old).

In the phantom, the magnitude of effects from changing the imaging parameters were smaller. Going from 20 diffusion directions to 12 resulted in mildly lower diffusivity values and (MD: −1.3%, RD: −2.1%, PD: +0.4%). Going from no parallel imaging to parallel imaging factor of two (both at 12 directions) resulted in further small changes (MD: −0.7%, RD: −0.2%, PD: −1.7%).

DISCUSSION

In this work, preliminary evaluation of OGSE diffusion was performed in a small cohort of six human subjects on the high amplitude (200 mT/m), high slew rate (500 T/m/s) MAGNUS platform at 3T. The peak cosine-OGSE frequency and b-value obtained with a nominal 50 ms waveform duration were 450 s/mm2 and 100 Hz, respectively. Various OGSE waveforms were compared to verify the spectra. Trapezoidal cosine-OGSE waveforms were found in simulation to provide the best isolation of frequency with increased b-values over sinusoidal cosine-OGSE. The head-PNS was found to be important in increasing b-values and to allow higher OGSE frequencies to be achieved.

In the in vivo human studies, a significant linear increase in MD, PD and RD was observed in majority of WM and GM parcels when frequency was increased. In WM, the increase in RD was faster than that in PD, resulting in a small decrease in FA with frequency. In GM, the lc values were more homogeneous than in WM (between RD and PD and also among the different GM parcels), which warrants future investigations. Linear fitting to D∞ (constant) and lc (slope) produced D∞ that were not dissimilar to PGSE diffusivity values, supporting the notion that PGSE results could also be included for f=0 Hz fitting. The lc obtained from our RD results in the genu, body and splenium of the corpus callosum were 0.69, 0.98 and 0.76 μm respectively, not dissimilar to the results of Burcaw (26) that simulated results from rhesus monkey corpus callosum (obtaining 0.65, 1.01, and 0.94 μm); accordingly, the DDR were 0.470, 0.948 and 0.570 μm2 respectively. As compared to the in vivo human results of Fieremans, et al. (25) using STEAM preparation rather than OGSE, the OGSE lc,RD for ACR, SCR, PCR and PLIC were about 3.5–5 times smaller than from STEAM, and the OGSE D∞,RD were about 30–40% higher than that from STEAM. These differences could be due to the much longer mixing times used in STEAM, or due to the relationship that was empirically obtained by the random packing simulation.(26) Linear fitting was excellent in RD but less so in PD, which would support the notion of short-range disorder (linear relationship frequency) for RD and long-range disorder (quadratic relationship with frequency) for PD that had been proposed (26). In our data we collected only five frequencies and at linear intervals, which could have been used but would be suboptimal for quadratic fitting. Furthermore, in this preliminary study the focus was to demonstrate the feasibility for OGSE human imaging with the head gradient coil, and to understand the b-value vs. frequency tradeoff. A future study with more OGSE frequencies, diffusivity directions and obtained at higher SNR would be beneficial in evaluating the validity of the disorder models.

The strong linear increase in OGSE diffusivity with frequency in human subjects compare very well with the much lower, almost negligible increase in the isotropic phantom. However, the preferential effects on PD in the phantom could indicate frequency-dependent vibration effects in OGSE than in PGSE, which had been a suggested explanation for measurement excursions in the OGSE literature (11). The MAGNUS gradient was designed to be force- and torque-balanced; a more detailed analysis of frequency-dependent vibrations on OGSE would be the subject of future studies. Nevertheless, there were other indications that the imaging parameters were close to the noise floor in this study, which could have increased the susceptibility of the metrics to vibration effects. For instance, reducing the number of diffusion directions also preferentially increased PD. The introduction of parallel imaging had a greater impact on OGSE than on PGSE, in particular the reduced RD and increased CoV. Linear fitting on a voxel-basis yielded fairly noisy maps (especially in PD); in this work fitting based on parcellated results seemed to be more reliable.

While the effects of changing the imaging parameters on the linear model were fairly small (<10%), this preliminary experience provides useful lessons learnt for optimizing future OGSE protocols and processing to increase SNR and CNR. The spatial resolution could be reduced slightly, along with incorporation of parallel imaging in-plane for further distortion reduction, and simultaneous multi-slice for scan time reduction. The number of frequencies could also be increased with weighting on higher frequencies for better quadratic fitting for PD. Denoising approaches (38,39), joint-fitting across frequencies (rather than per-frequency), and using different diffusivity directions for each frequency might improve the results of the disorder model. A comparison of STEAM and OGSE on the same system might be instructive for further validation of the disorder model.

The MAGNUS system tested utilized a 1-MVA per-axis gradient driver, which provided performance at 200 mT/m and 500 T/m/s. Modern clinical systems have begun to adopt drivers with higher peak power, which could allow MAGNUS to provide 300 mT/m and 700 T/m/s for 2-MVA per-axis. It would then be feasible to acquire about 150 Hz OGSE at b=500 s/mm2, or 100 Hz at 1250 s/mm2. For MAGNUS at 3-MVA per-axis, the performance can potentially reach 400 mT/m and 900 T/m/s, which could provide 150 Hz OGSE at b=615 s/mm2, or 100 Hz at b=2250 s/mm2. The primary limitation to attaining higher frequencies or b-values or frequencies is PNS, which in the MAGNUS head system could potentially be mitigated by careful positioning of the patient (23) or by improved gradient designs optimized for PNS (40). Clinical applications for high-frequency OGSE with ultra-strong gradients will be focused on probing of human tissue microstructure at smaller diffusion times or length scales than previously possible, which may lead to the discovery of novel imaging biomarkers, either combined with or separate from other diffusion tensor or kurtosis metrics. One example is to use OGSE to study the axonal microstructure in normal appearing white matter of neurocognitive or neurodegenerative disease, e.g. mild traumatic brain injury, chronic epilepsy, neurodevelopmental delay, non-lesional white matter in multiple sclerosis. Another example is to use OGSE to study tissue cellularity in neuro-oncology and to address diagnostic difficulties, e.g. differentiation of non-enhancing tumor from edema in the setting of a primary brain tumor or differentiation of recurrent tumor from radiation effects in the setting of a treated brain tumor.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Parameters of PGSE and OGSE diffusion pulse sequences used in the study.

Figure S1. Trapezoidal cosine OGSE pulse sequence, from 20 Hz to 100 Hz (left to right), and the respective combined spectrum from both waveforms.

Table S2. Acronym and full names of the 50 white matter parcels and 7 gray matter parcels.

Table S3. WM Mean diffusivity results (in μm2/s) for PGSE, and percentage difference of OGSE from PGSE (* indicates a statistically-significant difference, with P<0.05 deemed statistically-significant).

Table S4. WM Parallel diffusivity results (in μm2/s) for PGSE, and percentage difference of OGSE from PGSE (* indicates a statistically-significant difference, with P<0.05 deemed statistically-significant).

Table S5. WM Radial diffusivity results for PGSE (in μm2/s), and percentage difference of OGSE from PGSE (* indicates a statistically-significant difference, with P<0.05 deemed statistically-significant).

Table S6. WM Fractional Anisotropy results for PGSE, and percentage difference of OGSE from PGSE (* indicates a statistically-significant difference, with P<0.05 deemed statistically-significant).

Table S7. GM Results for PGSE, and percentage difference of OGSE from PGSE (* indicates a statistically-significant difference, with P<0.05 deemed statistically-significant).

Table S8. Mean diffusion dispersion ratio or DDR (in μm2, n=6) for the mean, parallel and radial diffusivity maps (MD, PD and RD respectively) per parcel. Blanked entries reflect results with poor fitting (with low correlation of R2<0.85).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors will like to thank Grant Yang, Flavio Dell’ Acqua, Steve Kecskemecti, Andy Alexander, Luca Marinelli, and John Schenck for useful discussions on brain microstructure modeling. We also thank Eric Fiveland for technical assistance on operating the MAGNUS gradient.

Grant support: CDMRP W81XWH-16-2-0054, NIH U01EB026976, NIH U01EB024450

APPENDIX

Derivation of frequency-dependence on gradient amplitude and slew rate

For a given sinusoidal waveform, of maximum amplitude G and frequency f, G(t) = Gmaxsin(2πft), the derivative of G, also known as slew rate is:

Therefore, SRmax is the maximum amplitude of that derivative, which is SRmax = 2πfGmax.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Schachter Does, Anderson A, Gore J Measurements of Restricted Diffusion Using an Oscillating Gradient Spin-Echo Sequence. J Magn Reson 2000;147:232 doi: 10.1006/jmre.2000.2203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Does MD, Gore JC. Compartmental study of diffusion and relaxation measured in vivo in normal and ischemic rat brain and trigeminal nerve. Magnet Reson Med 2000;43:837–844 doi: 10.1002/1522-2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Does MD, Parsons EC, Gore JC. Oscillating gradient measurements of water diffusion in normal and globally ischemic rat brain. Magnet Reson Med 2003;49:206 215 doi: 10.1002/mrm.10385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reese T, Heid O, Weisskoff R, Wedeen V. Reduction of Eddy-Current-Induced Distortion in Diffusion MRI Using a Twice-Refocused Spin Echo. Magnet Reson Med 2002;49:177 doi: 10.1002/mrm.10308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finsterbusch J Double-spin-echo diffusion weighting with a modified eddy current adjustment☆. Magn Reson Imaging 2010;28:434 doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2009.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang G, Tian Q, Leuze C, Wintermark M, McNab JA. Double diffusion encoding MRI for the clinic. Magnet Reson Med 2017;80:507 520 doi: 10.1002/mrm.27043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Westin C-F, Knutsson H, Pasternak O, et al. Q-space trajectory imaging for multidimensional diffusion MRI of the human brain. Neuroimage 2016;135:345 362 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.02.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szczepankiewicz F, van Westen D, Englund E, et al. The link between diffusion MRI and tumor heterogeneity: Mapping cell eccentricity and density by diffusional variance decomposition (DIVIDE). Neuroimage 2016;142:522 532 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.07.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drobnjak I, Zhang H, Ianuş A, Kaden E, Alexander DC. PGSE, OGSE, and Sensitivity to Axon Diameter in Diffusion MRI: Insight from a Simulation Study. Magnet Reson Med 2015;75:688 doi: 10.1002/mrm.25631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu J, Does MD, Gore JC. Sensitivity of MR diffusion measurements to variations in intracellular structure: Effects of nuclear size. Magnet Reson Med 2009;61:828 833 doi: 10.1002/mrm.21793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu J, Li K, Smith AR, et al. Characterizing Tumor Response to Chemotherapy at Various Length Scales Using Temporal Diffusion Spectroscopy. Plos One 2012;7:e41714 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aggarwal M, Jones MV, Calabresi PA, Mori S, Zhang J. Probing Mouse Brain Microstructure Using Oscillating Gradient Diffusion MRI. Magnet Reson Med 2011;67:98 doi: 10.1002/mrm.22981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu D, Li Q, Northington FJ, Zhang J. Oscillating gradient diffusion kurtosis imaging of normal and injured mouse brains. Nmr Biomed 2018;31:e3917 9 doi: 10.1002/nbm.3917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andica C, Hori M, Kamiya K, et al. Spatial Restriction within Intracranial Epidermoid Cysts Observed Using Short Diffusion-time Diffusion-weighted Imaging. Magn Reson Med Sci 2018;17:269 272 doi: 10.2463/mrms.cr.2017-0111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van AT, Holdsworth SJ, Bammer R. In vivo investigation of restricted diffusion in the human brain with optimized oscillating diffusion gradient encoding. Magnet Reson Med 2013;71:83 94 doi: 10.1002/mrm.24632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baron CA, Beaulieu C. Oscillating Gradient Spin-Echo (OGSE) Diffusion Tensor Imaging of the Human Brain. Magnet Reson Med 2013;72:726 doi: 10.1002/mrm.24987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Setsompop K, Kimmlingen R, Eberlein E, et al. Pushing the limits of in vivo diffusion MRI for the Human Connectome Project. Neuroimage 2013;80:220 233 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones D, Alexander D, Bowtell R, et al. Microstructural imaging of the human brain with a “super-scanner”: 10 key advantages of ultra-strong gradients for diffusion MRI. Neuroimage 2018;182:8 38 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.05.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foo T, Laskaris E, Vermilyea M, et al. Lightweight, compact, and high-performance 3T MR system for imaging the brain and extremities. Magnet Reson Med 2018;80:2232 2245 doi: 10.1002/mrm.27175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee S-K, Mathieu J-B, Graziani D, et al. Peripheral nerve stimulation characteristics of an asymmetric head-only gradient coil compatible with a high-channel-count receiver array. Magnet Reson Med 2016;76:1939 1950 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiger M, Overweg J, Rösler M, et al. A high‐performance gradient insert for rapid and short‐T2 imaging at full duty cycle. Magnet Reson Med 2018;79:3256–3266 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foo T, Graziani D, Hua Y, et al. MAGNUS: An ultra-high efficiency head-only gradient coil for imaging the brain microstructure. Proc ISMRM 2018:839. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan ET, Hua Y, Fiveland EW, et al. Peripheral nerve stimulation limits of a high amplitude and slew rate magnetic field gradient coil for neuroimaging. Magnet Reson Med 2019. doi: 10.1002/mrm.27909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Novikov D, Jensen J, Helpern J, Fieremans E. Revealing mesoscopic structural universality with diffusion. Proc National Acad Sci 2014;111:5088 5093 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316944111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fieremans E, Burcaw LM, Lee H-H, Lemberskiy G, Veraart J, Novikov DS. In vivo observation and biophysical interpretation of time-dependent diffusion in human white matter. Neuroimage 2016;129:414 427 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burcaw LM, Fieremans E, Novikov DS. Mesoscopic structure of neuronal tracts from time-dependent diffusion. Neuroimage 2015;114:18 37 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.03.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Innocenti G, Caminiti R, Aboitiz F. Comments on the paper by Horowitz et al. (2014). Brain Struct Funct 2015;220:1 2 doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0974-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santis S, Jones DK, Roebroeck A. Including diffusion time dependence in the extra-axonal space improves in vivo estimates of axonal diameter and density in human white matter. Neuroimage 2016;130:91 103 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.01.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu J, Li H, Li K, et al. Fast and simplified mapping of mean axon diameter using temporal diffusion spectroscopy. Nmr Biomed 2016;29:400–410 doi: 10.1002/nbm.3484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arbabi A, Kai J, Khan AR, Baron CA. Diffusion dispersion imaging: Mapping oscillating gradient spin-echo frequency dependence in the human brain. Magnet Reson Med 2019. doi: 10.1002/mrm.28083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan ET, Marinelli L, Slavens ZW, King KF, Hardy CJ. Improved correction for gradient nonlinearity effects in diffusion-weighted imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 2012;38:448–53 doi: 10.1002/jmri.23942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tao AT, Shu Y, Tan ET, et al. Improving apparent diffusion coefficient accuracy on a compact 3T MRI scanner using gradient nonlinearity correction. J Magn Reson Imaging 2018;48:1498 1507 doi: 10.1002/jmri.26201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bhushan C, Haldar JP, Choi S, Joshi AA, Shattuck DW, Leahy RM. Co-registration and distortion correction of diffusion and anatomical images based on inverse contrast normalization. Neuroimage 2015;115:269–280 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.03.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Avants BB, Tustison NJ, Song G, Cook PA, Klein A, Gee JC. A reproducible evaluation of ANTs similarity metric performance in brain image registration. Neuroimage 2011;54:2033–2044 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Avants BB, Epstein CL, Grossman M, Gee JC. Symmetric diffeomorphic image registration with cross-correlation: Evaluating automated labeling of elderly and neurodegenerative brain. Med Image Anal 2008;12:26–41 doi: 10.1016/j.media.2007.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tustison NJ, Avants BB. Explicit B-spline regularization in diffeomorphic image registration. Front Neuroinform 2013;7:39 doi: 10.3389/fninf.2013.00039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, et al. Automated Anatomical Labeling of Activations in SPM Using a Macroscopic Anatomical Parcellation of the MNI MRI Single-Subject Brain. Neuroimage 2002;15:273–289 doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Veraart J, Novikov DS, Christiaens D, Ades-aron B, Sijbers J, Fieremans E. Denoising of diffusion MRI using random matrix theory. Neuroimage 2016;142:394 406 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sperl JI, Sprenger T, Tan ET, Menzel MI, Hardy CJ, Marinelli L. Model‐based denoising in diffusion‐weighted imaging using generalized spherical deconvolution. Magnet Reson Med 2017;78:534 doi: 10.1002/mrm.26626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davids M, Guérin B, vom Endt A, Schad LR, Wald LL. Prediction of peripheral nerve stimulation thresholds of MRI gradient coils using coupled electromagnetic and neurodynamic simulations. Magnet Reson Med 2018;81:686 701 doi: 10.1002/mrm.27382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Parameters of PGSE and OGSE diffusion pulse sequences used in the study.

Figure S1. Trapezoidal cosine OGSE pulse sequence, from 20 Hz to 100 Hz (left to right), and the respective combined spectrum from both waveforms.

Table S2. Acronym and full names of the 50 white matter parcels and 7 gray matter parcels.

Table S3. WM Mean diffusivity results (in μm2/s) for PGSE, and percentage difference of OGSE from PGSE (* indicates a statistically-significant difference, with P<0.05 deemed statistically-significant).

Table S4. WM Parallel diffusivity results (in μm2/s) for PGSE, and percentage difference of OGSE from PGSE (* indicates a statistically-significant difference, with P<0.05 deemed statistically-significant).

Table S5. WM Radial diffusivity results for PGSE (in μm2/s), and percentage difference of OGSE from PGSE (* indicates a statistically-significant difference, with P<0.05 deemed statistically-significant).

Table S6. WM Fractional Anisotropy results for PGSE, and percentage difference of OGSE from PGSE (* indicates a statistically-significant difference, with P<0.05 deemed statistically-significant).

Table S7. GM Results for PGSE, and percentage difference of OGSE from PGSE (* indicates a statistically-significant difference, with P<0.05 deemed statistically-significant).

Table S8. Mean diffusion dispersion ratio or DDR (in μm2, n=6) for the mean, parallel and radial diffusivity maps (MD, PD and RD respectively) per parcel. Blanked entries reflect results with poor fitting (with low correlation of R2<0.85).