Abstract

This investigation examined the synergistic role of parental emotion-focused socialization behaviors and children’s perceptual sensitivity on children’s fear reactivity. A sample of 105 children with anxiety disorders (8–12 years; M = 10.07 years, SD = 1.22; 57% female) and their clinically anxious mothers (M = 39.35 years, SD = 7.05) completed an assessment battery that included a diagnostic interview and questionnaires regarding anxiety symptoms, perceptual sensitivity, and emotion socialization behaviors; children also completed a 5-minute, videotaped speech task, and rated their fear levels before and after the task. Analyses revealed a significant interaction between perceptual sensitivity and emotion-focused strategies predicting fear change scores from pre- to post-speech. Higher perceptual sensitivity was related to greater reductions in fear from pre- to post- speech (adjusting for pre-speech fear level), yet only among anxious children whose mothers reported high use of emotion-focused strategies. Maternal emotion-focused socialization strategies may increase anxious children’s ability to modulate their affective responses during stressful situations.

Keywords: emotion socialization, anxiety; children; fear; temperament; parenting

Childhood anxiety disorders are among the most common psychological disorders in youth, with an estimated yearly prevalence of 12.6% in children ages 6–12 years old [1]. Research also suggests that childhood anxiety disorders are associated with significant impairment across multiple domains [2], including social problems [3], sleep disturbances [4], and academic difficulties [5]. Childhood anxiety disorders also tend to persist into adulthood [6], thereby increasing risk for physical health, occupational, relationship, and comorbid mental health problems [7];[8];[9]. As a result, a better understanding of the underlying risk processes associated with increased fearful responses in anxious children has clear public health relevance.

Childhood anxiety symptoms have unique temperamental underpinnings [10]. Temperament is defined as biologically-based individual differences in emotional, motor, and attentional reactivity, and considered to be a developmental precursor of adult personality [11]. These biologically-based individual differences in emotion, self-regulation, and activity level [12] have been found to be related to the development of anxiety [2]; [13]; [14]. For instance, Clark and Watson [10] argued that negative emotionality—which encompasses a susceptibility to experiencing sad, fearful, anxious, and irritable affective states in reaction to stress- increases risk for internalizing disorders, including anxiety [11]; [12]. Likewise, a temperamental disposition to display fear or apprehension in unfamiliar situations (i.e., behavioral inhibition [13]) has been associated with the development of childhood anxiety disorders and social anxiety in particular [14]; [15].

A small, yet growing, number of studies have also focused on individual differences in perceptual sensitivity—a temperamental trait characterized by awareness of slight, low intensity stimulation arising from within the body and the environment [16]—in the context of anxiety [17]. Perceptual sensitivity is considered a facet of effortful control [18], a dispositional trait involved in top-down control of attention and self-regulation [19]. Higher effortful control in children (ages 8–12 years) has been consistently linked to better self-regulation and lower risk for psychopathology, including anxiety [20; 21].

Associations between perceptual sensitivity and anxiety suggest a nuanced relationship that may vary as a function of context, however. Specifically, higher perceptual sensitivity may serve as a protective factor in situations with a high likelihood of threat exposure. For example, evidence from studies with maltreated nine-year-old children suggests that increased perceptual sensitivity in the form of increased awareness and surveillance of affective expressions in the immediate environment (e.g., parents) may be advantageous [22]. Byrne and Eysenck [23] also found that individuals with high anxiety displayed higher perceptual sensitivity during a threatening facial recognition task than individuals with low anxiety. Thus, in a legitimately threatening context, a more sensitive environmental threat detection “system” (i.e., higher perceptual sensitivity) may allow individuals to process threats more efficiently.

Similarly, whether perceptual sensitivity serves an adaptive function among anxious children may depend on the nature of the emotional support the child receives. In the absence of parental supportive behaviors that can assist the child in managing stressful situations, enhanced perceptual sensitivity may cause the child to misinterpret internal and external stimuli (including bodily cues and facial expressions) [17] and experience heightened anxiety. On the other hand, in the context of supportive and emotion-focused parental emotion socialization behaviors, an anxious child with increased perceptual sensitivity may be able to detect environmental cues rapidly while avoiding interpretation of such cues as threatening.

Individual differences in perceptual sensitivity may also influence children’s fear reactivity (operationalized herein as changes in fear levels during an anxiety-provoking task). Specifically, children with an increased awareness of slight, interoceptive or external signals may more accurately appraise threat in the environment [22] and modulate fear responses accordingly. In contrast, children with lower perceptual sensitivity (i.e., less skilled at reading internal or external cues) may exhibit a more rigid fear response when faced with a stressor, thereby remaining fearful even after the threat has dissipated. To illustrate, imagine two anxious children are asked to perform a spelling task in front of the class. The child with high perceptual sensitivity may be better able to read external cues (e.g., children smiling, the teacher nodding) and use these cues to down-regulate his internal fear. The child with low perceptual sensitivity, on the other hand, may be less likely to accurately appraise the environment and may remain anxious throughout the task.

Although early experiences, such as exposure to parental anger expression and physical threats, in the context of the parent-child relationship are associated with the accuracy and speed of children’s recognition of emotions (e.g., anger [22]) the parental processes that may influence the relationship between children’s perceptual sensitivity and fear responses have not been examined, generally, or among anxious children, specifically. This is surprising, as past work has found evidence for the importance of considering the parenting context in which children’s temperamental traits influence behavior [24]. Parenting behaviors, including parental reactivity (i.e., parental emotional responses to children’s emotional expressions), parental sensitivity (i.e., soothing children’s distress), and the teaching of emotional coping can influence children’s expression of temperamental qualities such as inhibition, withdrawal, and negative affect [24]. Children’s temperamental characteristics, in turn, can also influence parenting behavior [25]. For example, Lengua and Kovacs [26] found that negative parenting behaviors, such as inconsistent discipline, may increase negative emotionality in children, which may in turn increase negative parenting behaviors. A separate study found direct associations between children’s positive affect and adaptive self-regulation and greater parental responsiveness, inclusion, and use of rewards [25]. Mindful parenting practices, which involve intentional moment-to moment awareness, listening with full attention, nonjudgmental acceptance of the child, and emotional awareness [27], may play a role in children’s perceptual sensitivity in particular. Specifically, these practices may foster emotion-focused behaviors in parents that, in turn, promote children’s awareness and sensitivity to their internal and external experiences [28]. Although clear evidence exists for synergistic associations between parenting processes and children’s temperament, the role of parental emotion socialization in the relation between children’s perceptual sensitivity and fear reactivity has not been examined.

Parental emotion socialization is defined as parental behavioral and affective responses that can influence children’s understanding, experience, expression, and regulation of emotions [29]. Children of parents who utilize supportive emotion socialization strategies, and more specifically emotion-focused strategies such as comforting or distracting children in order to help them feel better [30], exhibit increased emotional competency, better emotion regulation, and fewer internalizing problems [31; 32]. For example, upon hearing that her child was the victim of bullying on the school bus, a parent who uses emotion-focused strategies may respond by comforting and encouraging the child to discuss her emotional reactions to the situation [33]. Likewise, research has found that higher parental warmth and positive expressivity predicted higher empathy and social functioning among children over a two-year period [34].

In contrast, parental use of negative emotion socialization strategies, such as criticism of the child’s emotions or avoidance of emotional discussions, are associated with higher child anxiety [32] and difficulties understanding and expressing emotions [35]. Suveg and colleagues[35] also found that mothers of children with anxiety disorders used significantly fewer positive emotion words and engaged in more discouragement of their children’s emotional discussion than did mothers of non-anxious children. Research has also shown that anxious (vs. non-anxious) mothers exhibit higher levels of criticism and lower levels of autonomy granting toward their adolescent children [36]. Anxious parents also report higher levels of distress while their children (ages 7–12 years) engaged in routine age-appropriate activities [37], and endorsed significantly less emotional expressiveness and less cohesion [37], than non-anxious parents. Higher maternal anxiety has also been associated with less child-directed warmth and more modeling of anxious responses [38].

Although the above studies suggest that perceptual sensitivity is linked to anxiety [23]; [39], and parental use of emotion-focused behaviors may be protective against anxiety [32];[35], interactive effects between these variables in relation to anxious children’s fear reactivity have been understudied. This is surprising, given that emotion socialization strategies and emotion-focused behavior in particular have been found to moderate temperamental effects on internalizing psychopathology. Specifically, Engle and McElwain (2011) found interactive effects between parental unsupportive (punitive) reactions and child negative emotionality (a temperamental trait; [40]) on children’s internalizing behaviors. Specifically, higher levels of punitive reactions coupled with higher levels of child negative emotionality was related to greater internalizing symptoms among boys [41]. Similarly, Morris and colleagues found that among children (ages 7–8 years) high in irritability (a temperamental trait), increased maternal psychological control was related to increased internalizing difficulties, including anxiety [42]. Arguably, perceptually sensitive children who have been exposed to supportive parental emotion-focused behaviors (e.g., soothing responses, emotional validation, and enhancement of positive affect) may be better equipped to assess threat and modulate their fear responses accordingly. More specifically, these parental behaviors likely enhance (perceptually sensitive) children’s appreciation and understanding of their own emotional experiences relative to children of parents who display low levels of emotion-focused behaviors.

The present investigation examined the underlying role of parental emotion-focused socialization in the association between anxious children’s perceptual sensitivity and their change in fear reactivity in response to an anxiety-provoking speech task. It was hypothesized that parental emotion-focused socialization skills would moderate the association between children’s perceptual sensitivity and their fear reactivity; specifically, it was expected that higher perceptual sensitivity would be related to greater reduction in fear from pre- to post-speech among children of mothers who reported high (vs. low) use of emotion-focused socialization behaviors.

Method

Participants

The current study is based on secondary analyses of data from a larger study examining the effects of maternal interpretation biases parenting factors associated childhood anxiety disorders (e.g., [43]). Families were included if (a) the child was between the ages of 8–12, (b) the child had a primary anxiety disorder (by either mother or child report), (c) the mother reported levels of anxiety within the clinical range during clinical interview or on the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales [DASS; 44], and (d) the child currently lived with the mother. Children were excluded if they had (a) physical disability impairing ability to use a computer, (b) borderline or extremely low intellectual functioning, (c) below average reading comprehension, (d) concurrent primary diagnosis of any non-anxiety disorder, (e) been currently receiving psychological or pharmacological treatment for anxiety, or (f) demonstrated danger to self/others. Non-English speaking dyads were also excluded.

The final sample was comprised of 105 children with anxiety disorders between 8 and 12 years of age (M = 10.07 years, SD = 1.22; 57% female) and their clinically anxious mothers (M = 39.35 years, SD = 7.05; age range = 26 – 61 years; 67% married). Fifty one percent of the mothers identified as White, 30% as Hispanic, 14% as African American, 3% mixed ethnicity and 2% Asian American. Thirty nine percent of the children identified as White, 29% as Hispanic, 16% as mixed ethnicity 14% as African American, and 2% Asian American.

Children met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [5th ed.; 45] criteria for at least one anxiety disorder diagnosis based on results from semi-structured interviews conducted (separately) with both the child and the mother using the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-Kid [46]). Generalized Anxiety Disorder was the most common anxiety disorder (46.7%), followed by Social Anxiety Disorder (27.6%), Specific Phobias (16.2%), Separation Anxiety Disorder (7.6%), and Other Anxiety Disorders (1.9%). Most of the sample (69.5%) had comorbid diagnoses, the most common being specific phobias (14.3%), attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (12.4%), generalized anxiety disorder (8.6%), oppositional defiant disorder (7.6%), current major depressive disorder (7.6%), separation anxiety disorder (5.7%), and social anxiety disorder (5.7%).

Measures

MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID; [46])

The MINI-KID was used to ascertain whether children had a primary anxiety disorder, in order to determine eligibility for the study. The MINI-KID is a structured diagnostic interview that assesses the presence of current DSM-5 psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents aged 6-to-17 years old. The MINI-KID follows the same structure as the MINI as described above. The instrument screens for 24 of the most common DSM-IV psychiatric disorders. The MINI-KID has demonstrated high reliability and validity for children and adolescents [47].

In the present study, the MINI-KID Parent and Child versions were used. The parent version was used with the mother, who reported on her child’s symptoms, and the child version was used with the child, who reported on their own symptoms. Mother and child interviews were conducted separately, in adjacent rooms. MINI-KID interviews were conducted by a board-certified and licensed clinical child and adolescent psychologist, or an advanced graduate student under supervision. Graduate student assessors were trained to use the MINI-KID by observing videotaped samples of interviews conducted by the principal investigator; assessors were required to meet perfect inter-rater reliability with the PI on three interviews before conducting 2 independent interviews while being shadowed by the PI (i.e., live supervision). All MINI-KID interviews were videotaped and all diagnoses made were reviewed during supervision sessions with assessors. The PI also reviewed 15% of videotaped interviews for inter-rater reliability; no instances of diagnostic disagreement were found. The child’s final primary diagnosis was based on the clinical interview with the mother; if the mother did not report a primary diagnosis, but the child did, then the child’s final primary diagnosis was the self-reported diagnosis. Diagnostic agreement regarding the presence of a primary anxiety disorder across both mother and child interviews was observed for 48.6% of children; the remaining children received a primary anxiety disorder diagnosis based solely on the clinical interview with the mother (40%) or the child (11.4%).

Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire, Short Form (EATQ-RS; [48]

The EATQ-RS is a 65-item self-report measure designed to assess temperament traits in late childhood through late adolescence. All items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from almost always untrue (1) to almost always true (5). The measure includes 11 temperament subscales (activation control, activity level, affiliation, attention, fear, frustration, high intensity pleasure, inhibitory control, perceptual sensitivity, pleasure sensitivity, and shyness) and two behavioral scales (aggression and depressive mood). Subscale scores are obtained by averaging responses to items of each subscale (i.e., subscale scores range = 1 – 5). The EATQ-RS has demonstrated acceptable reliability and validity [49]. In this study, the perceptual sensitivity subscale was used (α = 0.72).

Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions Scale (CCNES; [33])

The CCNES is parent-completed measure of parental emotion socialization strategies. It consists of 12 vignettes of everyday situations involving children’s negative emotions. Each vignette has six possible parental responses, and parents rate each response in terms of the degree to which they are likely to respond in the same manner (1 = very unlikely to 7 = very likely). The CCNES yields the following six subscales (12-items each): (1) distress reactions, (2) punitive reactions, (3) expressive encouragement, (4) emotion-focused reactions, (5) problem-focused reactions, and (6) minimization reactions. The CCNES has been widely used and is psychometrically sound [30]; [50]. In this study, and in line with hypotheses, the emotion-focused reactions subscale (hereafter referred to as CCNES-EF; e.g., “If my child is afraid of injections and becomes quite shaky and teary while waiting for his/her turn to get a shot, I would comfort him/her before and after the shot;” and “If my child is going over to spend the afternoon at a friend’s house and becomes nervous and upset because I can’t stay there with him/her, I would distract my child by talking about all the fun he/she will have with his/her friend”) was used (α = 0.82).

Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS; [51])

SUDS ratings were collected from children before and after a speech task (see Procedure). Children rated their subjective fear regarding the speech task on a scale from 0–9 (0 = no fear; 9 = extreme fear). Immediately before giving the speech, children were asked “how afraid are you about giving this speech?” Following the speech, children were asked “how afraid are you right now?” A fear change score was computed by subtracting the post-speech fear rating from the pre-speech fear rating, such that a positive score is indicative of a reduction in fear from pre- to post-speech task.

Procedure

All procedures were approved by the University Institutional Review Board (IRB). Mothers and children were recruited to participate in a larger study on thoughts, feelings, and temperament in children through local advertisements, child-oriented events, and flyers. Mothers interested in participating contacted study staff via telephone or email or were contacted by study personnel via telephone. Prior to potential participation, study personnel gave interested mothers a description of the study and a brief screener was conducted to assess for child exclusionary criteria. An initial three-hour session was scheduled with eligible families.

Upon arrival, informed consent from mothers and informed assent from children were obtained. Both the mothers and children completed self-report questionnaires, and then clinical interviews were conducted by doctoral-level clinicians; all psychiatric assessments were reviewed by the PI during team meetings to confirm diagnoses. Per exclusionary criteria, cognitive and academic functioning were assessed through administration of a short form of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition [WISC-IV; Block Design and Vocabulary subtests; 52] and two subtests of the Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, Third Edition [WIAT-III; Reading Comprehension and Oral Reading Fluency subtests; 53].

Eligible participants returned to the laboratory to complete the second and final session of the study within two weeks of the first session. During this visit, mothers and children were given a 5-minute opportunity to plan a speech that the child would give about their family. Children were told that this speech would be rated later for quality by study personnel. Children completed the speech about their family in front of a recording video camera. Ratings of their subjective distress were collected immediately before and immediately after the speech task. Upon completion of the second session, the mother and child were fully debriefed. Information regarding the results of the diagnostic evaluation, recommended evidence-based treatments, and contact information of local mental health providers were made available to families. Families received $50 per session for their participation, and children were also able to choose a small toy after each session.

Data Analysis

First, bivariate correlational analyses were used to examine associations among study variables and to identify possible sociodemographic covariates (Table 1). Second, regression analyses were conducted to examine interactive effects between perceptual sensitivity and parental emotion-focused coping strategies predicting children’s fear change scores while adjusting for baseline levels of fear. The PROCESS macro [54] was used to compute regression analyses with centered means, 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals, and bootstrapping of 10,000 re-samples [55]. The interaction term, as well as tests of the simple slopes as +/− 1 SD of the mean level of the moderator, are automatically computed in PROCESS. The form of the interaction was examined both graphically, as per recommendations from Cohen and Cohen [56], and statistically[57] by examining the 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals for the effect of perceptual sensitivity on fear change scores at each level of the moderator (CCNES-EF).

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations and Descriptive Statistics (N = 105)

| Variable | Mean/% (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.57 (.50) | - | (1.0–2.0) | |||||

| 2. Age | 10.1 (1.22) | .13 | - | (8.0–12.0) | ||||

| 3. Ethnicity | 30% | .12 | .05 | - | (4.0–8.0) | |||

| 4. CCNES-EF | 5.67 (.91) | −.02 | −.05 | .02 | - | (2.0–7.0) | ||

| 5. EATQ-PS | 3.14 (.99) | .10 | .03 | .19* | .05 | - | (1.0–5.0) | |

| 6. SUDS change | 1.17 (2.48) | .09 | .03 | .22* | −.05 | .21* | - | (−9.0–7.0) |

Note: Gender: male = 0, female = 1. Ethnicity = 30% Hispanic. CCNES-EF = Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions Scale, emotion-focused coping subscale. EATQ-PS = Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire, Short Form, perceptual sensitivity subscale. SUDS change = Change in Subjective Units of Distress Scale from pre- to post-speech.

p<.05

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Correlations among study variables are presented in Table 1. Children’s ethnicity was significantly associated with perceptual sensitivity (r = 0.19, p = .047) and fear change scores (r = 0.22, p = 0.03). Independent-samples t-tests revealed that White children (M = 3.36, SD = 0.89) reported higher levels of perceptual sensitivity than Hispanic children (M = 2.82, SD = 0.99), t = −2.39, p = 0.02; White children also reported greater reductions (M = 1.54, SD = 2.25) in fear from pre- to post-speech relative to Hispanic children (M = 1.33, SD = 2.91), t = −2.27, p = 0.03. As a result, child ethnicity was included as a covariate in the regression analyses. Additionally, higher perceptual sensitivity was associated with a positive (i.e., reduction in fear from pre- to post-speech) fear change score (r = 0.21, p = 0.03). Independent-samples t-tests revealed no significant differences in pre- to post-speech fear scores (t = 0.94, p = 0.33) or perceptual sensitivity (t = 0.93, p = 0.76) between boys and girls.

Moderation Analyses

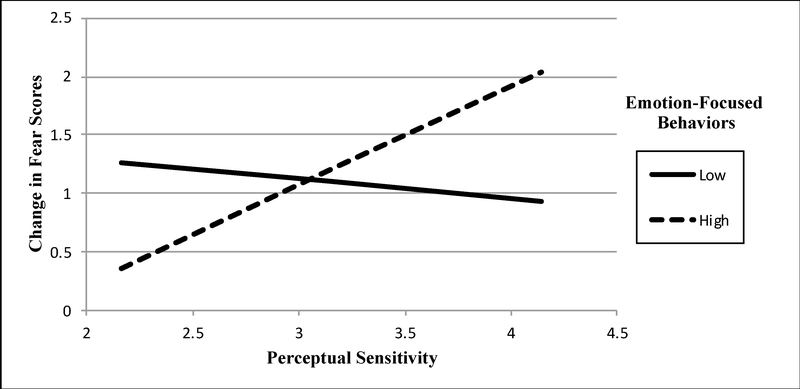

The overall model (controlling for children’s ethnicity and pre-speech fear levels) was significant and accounted for 26.7% of the total variance in fear change scores from pre- to post-speech (F (5, 98) = 7.15, p < 0.001). The interaction between EATQ-perceptual sensitivity and CCNES-EF strategies predicting fear change scores was also significant and accounted for 3% of the variance in fear change scores (B = 0.55, SE = 0.27; t = 2.06, p = 0.04; 95% CI [0.02, 1.08]). This finding was supported by examination of the simple slopes (see Figure 1), which revealed that the association between EATQ-perceptual sensitivity and fear change scores was significantly positive (i.e., the reader is reminded that a positive fear change score indicates a reduction in fear from pre- to post-speech) at high (+1 SD of the mean; B = 0.85, SE = 0.33; t = 2.57, p = .01; 95% CI [0.19, 1.50]) levels of CCNES maternal emotion-focused behaviors. However, at low levels of CCNES maternal emotion-focused behaviors, the association between EATQ-perceptual sensitivity and fear change scores was not significant (−1 SD of the mean; B = −0.16, SE = 0.33; t = −0.48, p = 0.63; 95% CI [ −0.82, 0.50]).

Figure 1.

Interaction between Perceptual Sensitivity and Emotion-Focused Coping on Change in Fear Scores, controlling for Child Ethnicity and Pre-Speech Fear Levels.

Note: At high levels of emotion-focused behavior the relationship between perceptual sensitivity and fear reactivity was significant. At low levels of emotion-focused behavior, this relationship was not significant. Positive change in fear scores indicates a reduction in fear from pre- to post-speech.

Discussion

The present investigation examined interactive effects between parental emotion socialization strategies and children’s perceptual sensitivity in relation to children’s fear reactivity in a large and diverse sample of children with anxiety disorders. Consistent with hypotheses, parental emotion-focused socialization skills significantly moderated the association between children’s perceptual sensitivity and children’s fear reactivity, such that among children of high (vs. low) emotion-focused mothers, higher perceptual sensitivity was related to greater reduction in fear from pre- to post-speech (even after adjusting for pre-level of fear; Figure I). These findings suggest that in the context of maternal emotion-focused behaviors, an enhanced awareness of internal and external stimuli may allow anxious children to more effectively modulate affective responses to stressful situations. Such a proposition is consistent with findings that supportive maternal emotion socialization is associated with lower anxiety in children [31];[32]. Specifically, Hurrell and colleagues [32] found that mothers of non-anxious children ages 7–12 years displayed more supportive reactions in response to their child’s negative emotions compared to mothers of anxious children. Notably, in the present study, the relationship between children’s perceptual sensitivity and their fear reactivity was not significant at low levels of parental emotion-focused strategy use. Thus, results from the current study suggest that children of mothers with lower use of emotion-focused strategies may display more rigid fear responses. On the other hand, in the context of maternal emotion-focused behaviors, an enhanced awareness of internal and external stimuli may allow anxious children to more effectively modulate affective responses to stressful situations.

Results from moderation analyses also suggest that there may be theoretical parallels between perceptual sensitivity and other forms of interoceptive sensitivity, such as anxiety sensitivity. Anxiety sensitivity, defined as an individual difference variable characterized by misinterpretations of internal and external anxiety sensations [58], has been found to be a robust predictor of anxiety across numerous investigators [59]; [60]. We posit that perceptual sensitivity may be thought of as an adaptive counterpart to anxiety sensitivity. Specifically, whereas the child with anxiety sensitivity erroneously interprets internal and external sensations as potentially catastrophic [61], the perceptually sensitive child may asess subtle interoceptive and external cues more adaptively—especially in the context of emotion-focused parenting. In line with this posibility, treatment of anxiety sensitivity has typically involved teaching individuals how to perceive and interpret anxiety sensations accurately, as well as to habituate to these sensations [62]; [63]. Although warranting further study, it is possible that such treatments may work because they are helping individuals develop a more nuanced perception (i.e., perceptual sensitivity) of the true meaning of their anxiety-related sensations.

Although not the primary focus of the present investigation, several other findings are worth noting. First, racial differences were found in perceptual sensitivity between Hispanic and White children, such that White children reported higher levels of perceptual sensitivity than did Hispanic children. Previous research has found differences in maternal reporting of children’s temperament across ethnic groups. Specifically, McClowry [64] found that Hispanic mothers disproportionately endorsed their school-aged children’s temperaments as challenging (including “high maintenance” and “cautious/slow to warm up”) compared to mothers of Black and White children. Second, racial differences in fear change scores were also found between Hispanic and White children, such that White children reported a greater reduction in fear than did Hispanic children. Research involving infants revealed that Hispanic mothers rated their infants as more fearful and less predictable than non-Hispanic European American mothers [65]. Results from the current study may thus reflect racial differences in parent-reported temperament and child-reported fear across ethnic groups. Similarly, research has found that the effects of supportive emotion socialization practices on children’s school and social competency may vary as a function of racial/ethnic status, highlighting the need for emotion socialization research to consider the child’s cultural context [66].

The present investigation has several clinical implications. First, the findings suggest that interventions aimed at enhancing anxious children’s ability to accurately and effectively interpret internal and external cues may serve to reduce their anxiety during fear-provoking situations only in the context of high levels of parental emotion-focused responses. In this vein, studies with adult samples have found that targeting erroneous beliefs about the meaning of interoceptive cues (e.g., sweating, increased heart rate) reduces anxiety and increases tolerance of physiological symptoms of anxiety [67]; [68]. Recent work has also examined the use of biofeedback technology to assist anxious individuals in identifying inaccuracies in perceived physiological arousal. For example, recent work involving biofeedback through the use of respiration and heart rate monitoring has been shown to be successful in decreasing anxiety symptoms [69]. The current study results also highlight the importance of the emotion socialization context within which children’s anxiety occurs, and the important role that parental behavior can play in child anxiety outcomes. Indeed, Lebowitz, Omer, Hermes, and Scahill [70] found that a parent-only treatment that helped parents to model self-regulation and reduce parental accommodation was effective in reducing child anxiety symptoms. Results from the present study support ongoing efforts to focus on parental behavioral modification, including emotion socialization practices, as a powerful tool in the treatment of childhood anxiety disorders. Future studies might specifically consider examining whether emotion-focused parental behaviors change in the context of exposure-based treatments for childhood anxiety or whether targeting these parental behaviors adjunctively is warranted.

The findings also underscore supportive parental emotion socialization strategies, such as the use of emotion-focused behaviors in response to child distress [29; 71], as the context in which children’s accurate perceptions of their internal and external experience may be expressed. Indeed, research has found that parental emotion socialization, including emotion-focused behaviors, can influence children’s understanding, experience, expression, and regulation of emotions[29]. Similarly, Suveg, Zeman, Flannery-Schroeder, & Cassano [35] found that increased parental focus on emotional discussions and expressions may influence children’s development of emotional competence. Specifically, Suveg and colleagues [35] found that parents of anxious children were less likely to engage in explanatory discussion of emotion and were more likely to discourage their children’s emotional expression relative to parents of nonanxious children. Finally, results from the present investigation suggest that incorporating parental emotion socialization skills training in the context of established protocols for childhood anxiety (e.g., teaching parents how to respond to child distress in a way that makes them feel validated and supported) may influence children’s perceptions of emotions and their capacity to modulate their fear responses. Currently, many extant treatment protocols include targeted interventions for parental emotional and behavioral responses to their children’s anxiety (e.g., differential attention, fading of safety behaviors, reduction of accommodation); however, results from the current study suggest that specific inclusion of emotion-focused responses (e.g., strategies aimed at helping children to feel better by focusing on acceptance of their emotional experience) may enhance existing treatment protocols.

The current study is not without limitations. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the design, it is not possible to determine the true direction of the relationships between perceptual sensitivity and anxiety symptoms. Additionally, the variables of interest, including fear reactivity, perceptual sensitivity and emotion-focused parenting behaviors were not related at the bivariate level. These results suggest that associations between perceptual sensitivity and fear reactivity may be present only in the context of emotion-focused parental behaviors. Although temperamental variables are thought to be a precursor to the emergence of anxiety symptoms [13], it is possible that the repeated experience of anxiety also influences perceptual sensitivity. Additionally, parental practices, including emotion socialization, were measured with parent-report questionnaires. Parental emotion socialization processes may be more robustly captured using behavioral and observational methods. For example, work by Suveg, Zeman, Flannery-Schroeder, and Cassano [35] has utilized behavioral observation to capture these constructs in a more rigorous fashion. The current study also relied on a clinical sample of children with anxiety disorders and their clinically anxious mothers, which limits the generalizability of the results to non-clinical samples where maternal emotion socialization skills may be qualitatively different [35].

Additionally, the social nature of the task may have been most salient to children with social anxiety concerns for whom social tasks are particularly stressful. Unfortunately, the sample size did not allow for statistical comparisons across diagnostic groups. However, past research has utilized similar speech tasks to elicit moderate psychosocial stress across to diverse groups of children including those with various anxiety disorders, social anxiety, and PTSD [72]. Future research with a larger sample size should include a combination non-social and social stressor tasks to evaluate potential task effects. An additional limitation pertains to the relatively small sample size to test interactive effects. As such, although intriguing, the current results should be interpreted with caution until they are replicated using a large sample with more robust statistical power to detect small interactive effects. Finally, the current study measured fear reactivity through children’s self-reported distress immediately before and after the speech, and not during the speech. Thus, it is possible that some children provided low ratings after the speech because they were relieved that the task was over, and not because the speech was actually less scary for them. Future studies should incorporate assessment of fear during the stressor task to more accurately model fear reactivity. Likewise, some children may have provided lower fear ratings after the speech due to social desirability bias (e.g., wanting to appear brave). The inclusion of physiological and observational measures in future research would be a welcome addition in order to complement the assessment of subjective fear responses.

Summary

Overall, the current study found support for an interactive effect between maternal use of emotion-focused behaviors and children’s perceptual sensitivity in relation to their fear reactivity during an anxiety-provoking speech task. Specifically, higher perceptual sensitivity was related to greater reductions in fear from pre- to post-speech, yet only among anxious children whose mothers reported high use of emotion-focused strategies in response to their children’s distress. Future investigations should evaluate whether targeting maternal emotion-focused behaviors leads to clinically-relevant improvements in the perception and modulation of fear responses among children with anxiety disorders.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grant R21MH101309 (PI: Viana) from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Research involving Human Participants and/or Animals: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Costello EJ, Egger HL, Copeland W, Erkanli A, Angold A (2011) The developmental epidemiology of anxiety disorders: phenomenology, prevalence, and comorbidity In: Field AP, Silverman WK (eds) Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 56–75 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beesdo K, Knappe S, Pine DS (2009) Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatric Clin 32:483–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.La Greca AM, Lopez N (1998) Social anxiety among adolescents: linkages with peer relations and friendships. Journal Abnorm Child Psychol 26:83–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramsawh HJ, Stein MB, Belik S-L, Jacobi F, Sareen J (2009) Relationship of anxiety disorders, sleep quality, and functional impairment in a community sample. J Psychiatr Res 43:926–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hughes AA, Lourea-Waddell B, Kendall PC (2008) Somatic complaints in children with anxiety disorders and their unique prediction of poorer academic performance. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 39:211–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y (1998) The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Arch Gen Psychiat 55:56–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisen AR, Engler LB (1995) Chronic anxiety In: Eisen AR, Kearney CA, Schaefer CA (eds) Clinical handbook of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Aronson, Northvale, NJ, pp 223–250 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benjamin RS, Costello EJ, Warren M (1990) Anxiety disorders in a pediatric sample. J Anxiety Disord 4:293–316 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costello EJ, Egger H, Angold A (2005) 10-year research update review: the epidemiology of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: I. methods and public health burden. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 44:972–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clark LA, Watson D (1991) Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. J Abnorm Psychol 100:316–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chorpita BF, Barlow DH (1998) The development of anxiety: the role of control in the early environment. Psychol Bull 124:3–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisenberg N, Sadovsky A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Losoya SH, Valiente C, et al. (2005) The relations of problem behavior status to children’s negative emotionality, effortful control, and impulsivity: concurrent relations and prediction of change. Dev Psychol 41:193–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N (1987) The physiology and psychology of behavioral inhibition in children. Child Dev 58:1459–1473 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kagan J (1989) Temperamental contributions to social behavior. Am Psychol 44:668–674 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Rosenbaum JF, Herot C, Friedman D, Snidman N, et al. (2001) Further evidence of association between behavioral inhibition and social anxiety in children. Am J Psychiatry 158:1673–1679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans DE, Rothbart MK (2008) Temperamental sensitivity: two constructs or one? Pers Individ Dif 44:108–118 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frenkel TI, Lamy D, Algom D, Bar-Haim Y (2009) Individual differences in perceptual sensitivity and response bias in anxiety: evidence from emotional faces. Cogn Emot 23:688–700 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim-Spoon J, Deater-Deckard K, Calkins SD, King-Casas B, Bell MA (2019) Commonality between executive functioning and effortful control related to adjustment. J Appl Dev Psychol 60:47–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nigg JT (2017) Annual Research Review: On the relations among self-regulation, self-control, executive functioning, effortful control, cognitive control, impulsivity, risk-taking, and inhibition for developmental psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 58:361–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muris P, van der Pennen E, Sigmond R, Mayer B (2008) Symptoms of anxiety, depression, and aggression in non-clinical children: relationships with self-report and performance-based measures of attention and effortful control. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 39:455–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raines EM, Viana AG, Trent ES, Woodward EC, Candelari AE, Zvolensky MJ, et al. (2019) Effortful control, interpretation biases, and child anxiety symptom severity in a sample of children with anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord 67:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pollak SD, Messner M, Kistler DJ, Cohn JF (2009) Development of perceptual expertise in emotion recognition. Cognition 110:242–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byrne A, Eysenck MW (1995) Trait anxiety, anxious mood, and threat detection. Cogn Emot 9:549–562 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lonigan CJ, Phillips BM (2001) Temperamental influences on the development of anxiety disorders In: Vasey MW, Dadds MR (eds) The developmental psychopathology of anxiety. Oxford University Press, New York, NY, US, pp 60–91 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Putnam SP, Sanson AV, Rothbart MK (2002) Child temperament and parenting. Handb Parent 1:255–277 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lengua LJ, Kovacs EA (2005) Bidirectional associations between temperament and parenting and the prediction of adjustment problems in middle childhood. J Appl Dev Psychol 26:21–38 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duncan LG, Coatsworth JD, Greenberg MT (2009) A model of mindful parenting: implications for parent–child relationships and prevention research. Clin Child Fam Psych 12:255–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bögels S, Hoogstad B, van Dun L, de Schutter S, Restifo K (2008) Mindfulness training for adolescents with externalizing disorders and their parents. Behav Cogn Psychother 36:193–209 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL (1998) Parental socialization of emotion. Psychol Inq 9:241–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fabes RA, Poulin RE, Eisenberg N, Madden-Derdich DA (2002) The coping with children’s negative emotions scale (CCNES): psychometric properties and relations with children’s emotional competence. Marriage Fam Rev 34:285–310 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eisenberg N (2002) Emotion-related regulation and its relation to quality of social functioning. Minn Sym Child Psych 32:133–171 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hurrell KE, Hudson JL, Schniering CA (2015) Parental reactions to children’s negative emotions: relationships with emotion regulation in children with an anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord 29:72–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fabes RA, Eisenberg N, Bernzweig J (1990) The coping with children’s negative emotions scale: procedures and scoring. Available from authors Arizona State University [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou Q, Eisenberg N, Losoya SH, Fabes RA, Reiser M, Guthrie IK, et al. (2002) The relations of parental warmth and positive expressiveness to children’s empathy-related responding and social functioning: a longitudinal study. Child Dev 73:893–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suveg C, Zeman J, Flannery-Schroeder E, Cassano M (2005) Emotion socialization in families of children with an anxiety disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol 33:145–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ginsburg GS, Grover RL, Ialongo N (2005) Parenting behaviors among anxious and non-anxious mothers: relation with concurrent and long-term child outcomes. Child Fam Behav Ther 26:23–41 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turner SM, Beidel DC, Roberson-Nay R, Tervo K (2003) Parenting behaviors in parents with anxiety disorders. Behav Res Ther 41:541–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Drake KL, Ginsburg GS (2011) Parenting practices of anxious and nonanxious mothers: a multi-method, multi-informant approach. Child Fam Behav Ther 33:299–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hofmann SG, Bitran S (2007) Sensory-processing sensitivity in social anxiety disorder: relationship to harm avoidance and diagnostic subtypes. J Anxiety Disord 21:944–954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rothbart MK (2007) Temperament, development, and personality. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 16:207–212 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Engle JM, McElwain NL (2011) Parental reactions to toddlers’ negative emotions and child negative emotionality as correlates of problem behavior at the age of three. Soc Dev 20:251–271 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Sessa FM, Avenevoli S, Essex MJ (2002) Temperamental vulnerability and negative parenting as interacting predictors of child adjustment. J Marriage Fam 64:461–471 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Viana AG, Palmer CA, Zvolensky MJ, Alfano CA, Dixon LJ, Raines EM (2017) Children’s behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorder symptom severity: the role of individual differences in respiratory sinus arrhythmia. Behav Res Ther 93:38–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH (1995) The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behav Res Ther 33:335–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Author, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. (1998) The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 59:22–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sheehan DV, Sheehan KH, Shytle RD, Janavs J, Bannon Y, Rogers JE, et al. (2010) Reliability and validity of the mini international neuropsychiatric interview for children and adolescents (MINI-KID). J Clin Pyschiatry 71:313–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ellis LK, Rothbart MK (2001) Revision of the early adolescent temperament questionnaire.Paper presented at biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development Minneapolis, MN [Google Scholar]

- 49.Capaldi DM, Rothbart MK (1992) Development and validation of an early adolescent temperament measure. J Early Adolesc 12:153–173 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Halberstadt AG, Dunsmore JC, Bryant A Jr, Parker AE, Beale KS, Thompson JA (2013) Development and validation of the parents’ beliefs about children’s emotions questionnaire. Psychol Assess 25:1195–1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolpe J (1958) Psychotherapy by reciprocal inhibition: Stanford Uni. Press, CA, pp 130–135 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wechsler D (2003) Wechsler intelligence scale for children–fourth edition (WISC-IV). The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wechsler D (2009) Wechsler individual achievement test-third edition (WIAT-III). Pearson; San Antonio, TX [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hayes AF (2012) PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling.

- 55.Hayes AF (2013) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis : a regression-based approach. Guilford Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cohen J, Cohen P (1983) Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences.2nd edn. L. Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holmbeck GN (2002) Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. J Pediatr Psychol 27:87–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reiss S (1991) Expectancy model of fear, anxiety, and panic. Clin Psychol Rev 11:141–153 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reiss S, Peterson RA, Gursky DM, McNally RJ (1986) Anxiety sensitivity, anxiety frequency and the prediction of fearfulness. Behav Res Ther 24:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schmidt NB, Zvolensky MJ, Maner JK (2006) Anxiety sensitivity: prospective prediction of panic attacks and axis I pathology. J Psychiatr Res 40:691–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weems CF, Costa NM, Watts SE, Taylor LK, Cannon MF (2007) Cognitive errors, anxiety sensitivity, and anxiety control beliefs: their unique and specific associations with childhood anxiety symptoms. Behav Modif 31:174–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Keough ME, Schmidt NB (2012) Refinement of a brief anxiety sensitivity reduction intervention. J Consult Clin Psychol 80:766–772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Deacon B, Kemp JJ, Dixon LJ, Sy JT, Farrell NR, Zhang AR (2013) Maximizing the efficacy of interoceptive exposure by optimizing inhibitory learning: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 51:588–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McClowry SG (2002) The temperament profiles of school-age children. J Pediatr Nurs 17:3–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lahey BB, Van Hulle CA, Keenan K, Rathouz PJ, D’Onofrio BM, Rodgers JL, et al. (2008) Temperament and parenting during the first year of life predict future child conduct problems. J Abnorm Child Psychol 36:1139–1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nelson JA, Leerkes EM, Perry NB, O’Brien M, Calkins SD, Marcovitch S (2013) European-american and african-american mothers’ emotion socialization practices relate differently to their children’s academic and social-emotional competence. Soc Dev 22:485–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Butler G, Fennell M, Hackmann A (2008) Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders (guides to individualized evidence-based treatment). Guilford Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wells A (2007) Cognition about cognition: metacognitive therapy and change in generalized anxiety disorder and social phobia. Cogn Behav Pract 14:18–25 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Domschke K, Stevens S, Pfleiderer B, Gerlach AL (2010) Interoceptive sensitivity in anxiety and anxiety disorders: an overview and integration of neurobiological findings. Clin Psychol Rev 30:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lebowitz ER, Omer H, Hermes H, Scahill L (2014) Parent training for childhood anxiety disorders: the SPACE program. Cogn Behav Pract 21:456–469 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thompson RA, Meyer S (2007) Socialization of emotion regulation in the family In: Gross JJ (ed) Handbook of emotion regulation. Guilford Press, New York, NY, pp 249–268 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kudielka BM, Hellhammer DH, Kirschbaum C, Harmon-Jones E, Winkielman P (2007) Ten years of research with the trier social stress test—revisited In: Harmon-Jones E, Winkielman P (eds) Social neuroscience. Guilford Press, New York, NY, pp 56–83 [Google Scholar]