Abstract

Background

Atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome (aHUS) is a life-threatening, genetic disease of complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathy that typically presents as anaemia, thrombocytopenia, and renal failure. Cardiomyopathy is seen in up to 10% of aHUS cases, but the aetiology is not well-understood.

Case summary

A 63-year-old man recently was diagnosed with a thrombotic microangiopathy most consistent with aHUS by renal biopsy after presentation with acute renal failure requiring haemodialysis. He was started on therapy with complement inhibitor, eculizumab. Six weeks after diagnosis, he presented with progressive dyspnoea on exertion and chest pain. An echocardiogram demonstrated an acute drop in left ventricular ejection fraction to 20–25% with global hypokinesis. Left heart catheterization showed moderate, non-obstructive coronary artery disease. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated diffuse myocardial oedema. Endomyocardial biopsy revealed an arteriole with obliterative changes and a few possible fragmented red blood cells suggestive of thrombotic microangiopathy. There was no biopsy evidence of immune complex deposition or myocarditis. He was treated for heart failure and was maintained on eculizumab. On repeat echocardiogram 3 months later, the patient had complete recovery of his ejection fraction (60–65%).

Discussion

In this report, we describe complete recovery of aHUS-associated heart failure with eculizumab therapy and demonstrate for the first time that the aetiology of aHUS-associated heart failure is likely an acute thrombotic microangiopathy involving small intramyocardial arterioles, as demonstrated by cardiac biopsy.

Keywords: Thrombotic microangiopathy, Non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy, Heart failure recovery, Eculizumab, Atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome, Case report

Learning points

Atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome (aHUS) is a rare disorder due to uncontrolled complement activation characterized by the triad of microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia, thrombocytopenia, and acute renal failure. Acute systolic heart failure is found in up to 10% of cases. The likely shared aetiology is acute thrombotic microangiopathy.

Eculizumab, a complement inhibitor, therapy can sometimes reverse both aHUS mediated renal and cardiac failure over the treatment course of weeks to months.

Introduction

Haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS) is a rare disorder characterized by the triad of microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia, thrombocytopenia, and acute renal failure.1 Typical HUS is caused by Shiga toxin produced by Escherichia coli O157:H7 and often occurs in children after an acute gastrointestinal illness. Atypical HUS (aHUS) is a disease of uncontrolled complement activation that can occur at any age. Most patients have a genetic predisposition to aHUS with gain-of-function mutations or other mutations in complement regulatory proteins that result in complement system dysregulation.2 In other patients, complement activating autoantibodies can be triggered by infections, pregnancy, drugs, or autoimmune disorders.1 Uncontrolled complement activation leads to the formation of membrane attack complex, endothelial damage, and activation of the coagulation cascade. The resultant thrombotic microangiopathy of aHUS primarily affects the kidneys. Extra-renal manifestations of aHUS are rare. The incidence aHUS-associated cardiomyopathy, characterized by acute systolic heart failure, is up to 10%.3

Timeline

| First presentation | Patient presented with dyspnoea and lower extremity oedema. On arrival, he was found be in acute renal failure with a normal echocardiogram, ejection fraction (EF) 60–65%. Over a 3 week hospitalization, patient was diagnosed with atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome, started intermittent haemodialysis therapy, and initiated biweekly eculizumab infusions. | |

| 1 week prior to representation | Patient develops worsening dyspnoea on exertion and chest pain. | |

| 2nd admission | Initial evaluation | Electrocardiogram without acute ischaemic changes, computed tomography scan without evidence of pulmonary embolism, chest X-ray with large bilateral pleural effusions. Underwent thoracentesis. |

| Hospital Day 1 | Echocardiogram with EF 20–25%. | |

| Intermittent haemodialysis continued for volume management. | ||

| Hospital Day 2–6 | Started on carvedilol and lisinopril. | |

| Cardiac catheterization demonstrated moderate, non-obstructive coronary artery disease. | ||

| Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated diffuse myocardial oedema. | ||

| Cardiac biopsy suggested thrombotic microangiopathy. | ||

| Hospital Day 7 | Patient discharged home to continue biweekly eculizumab and intermittent haemodialysis. | |

| 1 week post-discharge | Lisinopril stopped due to symptomatic hypotension. | |

| 3 months post-discharge | Echocardiogram with recovered systolic function 60–65%. | |

Case presentation

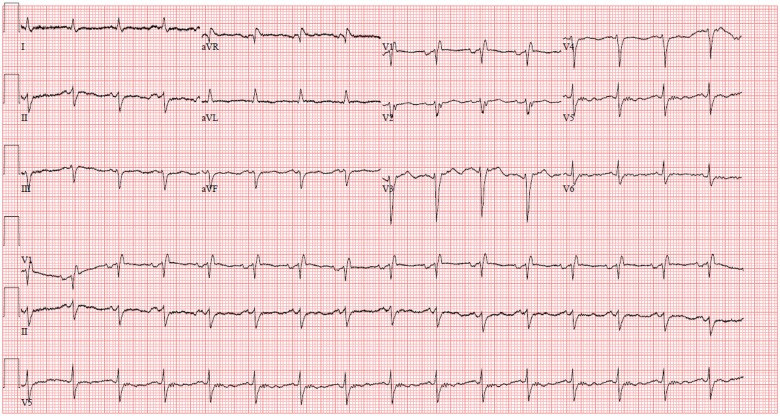

A 63-year-old man with a history of renal adenocarcinoma status post-nephrectomy, paroxysmal atrial flutter on diltiazem 240 mg daily, obstructive sleep apnoea, and scleroderma on prednisone 10 mg daily initially presented with a several week history of orthopnoea, dyspnoea on exertion, and bilateral lower extremity oedema. On admission, his estimated glomerular filtration rate was 18 mL/min/m2 with anaemia (haemoglobin 9.7 g/dL, reference range 13.4–16.8 g/dL) and normal platelet count (306 K/µL, reference range 146–337 K/µL). Initial echocardiogram demonstrated a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 60–65% with normal left ventricular end-diastolic volume (EDV) of 122.5 mL (EDV index 60.1 mL/m2), normal right ventricular size and systolic function, no pulmonary hypertension, and mild tricuspid regurgitation. The first week, he clinically worsened, responding poorly to diuresis and required haemodialysis. His platelet count dropped over 40% (166 K/µL) and his haemoglobin decreased to 8.8 g/dL. He had evidence of haemolysis with undetectable haptoglobin <30 mg/dL (reference range 44–215 mg/dL) and elevated lactate dehydrogenase 314 U/dL (reference range 100–190 U/dL). Given his ongoing renal failure with no clear aetiology, he underwent a renal biopsy (Figure 1). Pathology was consistent with thrombotic microangiopathy. ADAMTS13 was normal, ruling out thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Genetic analysis revealed a copy number variant in a complement regulator protein, CFHR3-1. With thrombocytopenia, haemolytic anaemia, and acute renal failure with thrombotic microangiopathy on biopsy, he was diagnosed with aHUS. He was started on therapy with the terminal complement inhibitor, eculizumab. He received eculizumab 1200 mg intravenously every 2 weeks.

Figure 1.

Renal biopsy showing a bloodless glomerulus with an ischaemic appearance and nearby small artery with endothelial swelling and subendothelial entrapped red blood cells (black arrow), consistent with thrombotic microangiopathy. Also, note significant luminal occlusion of a glomerular afferent arteriole (white arrow) with entrapped red blood cells within the wall. Haematoxylin and eosin, 200×.

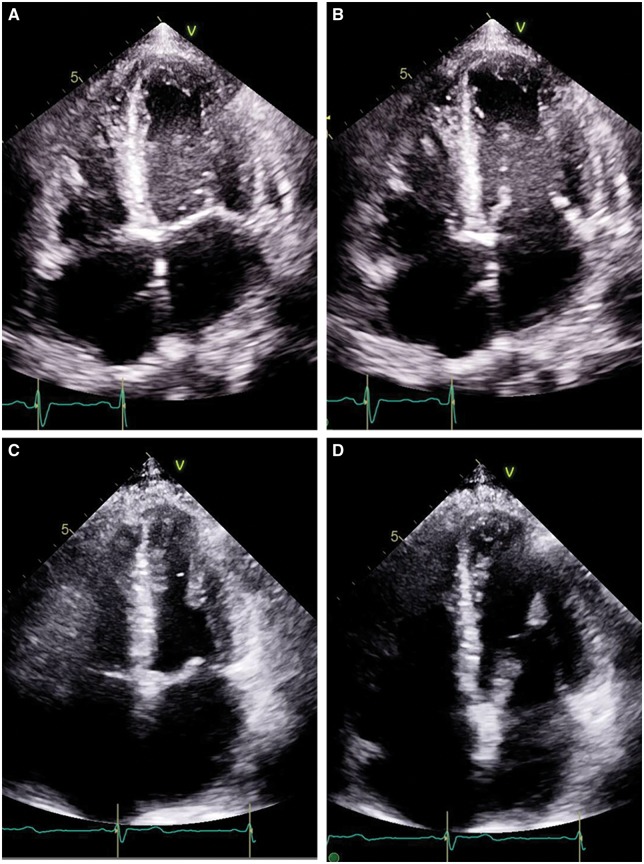

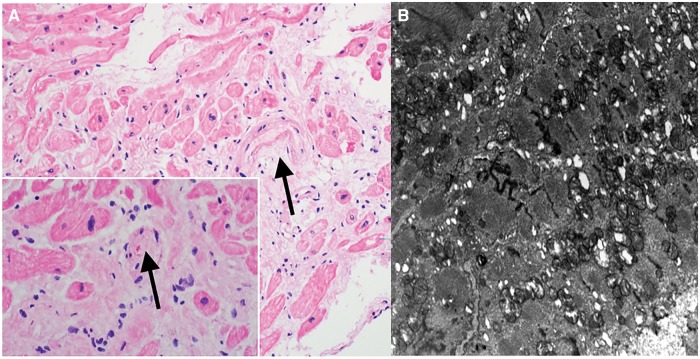

Six weeks after diagnosis with aHUS, he presented with progressive dyspnoea on exertion, hypoxia, and chest pain. Initial evaluation included an electrocardiogram (ECG) without acute ischaemic changes (Figure 2), computed tomography scan without evidence of pulmonary embolism, and chest X-ray with large pleural effusions. He was hypoxic to 66% on room air and required 7 L oxygen by nasal cannula. After an emergent thoracentesis with removal of 1500 mL of fluid, his hypoxia improved. Initial labs were remarkable for an elevated troponin level (peak 0.21 ng/mL, reference range <0.11 ng/mL). An echocardiogram demonstrated an acute drop in LVEF to 20–25% with global hypokinesis (Figure 3A and B). He had a family history of early coronary artery disease in his father and brother. He never smoked, did not drink alcohol and did not use illicit drugs. His vital signs included a heart rate of 95 b.p.m. and hypertension with blood pressure range of 134/93 to 167/97 mmHg. Physical exam was notable for bibasilar crackles, elevated jugular venous pressure, regular heart rhythm without murmurs and non-displaced point of maximal impulse, and no lower extremity oedema.

Figure 2.

Electrocardiogram without ischaemic changes.

Figure 3.

Echocardiogram four-chamber view in patient with atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome associated acute systolic heart failure (A) systole and (B) diastole during initial presentation with estimated left ventricular ejection fraction of 20–25% and then 3 months later, the same four-chamber view (C) systole and (D) diastole after complete recovery with an estimated ejection fraction of 60–65%.

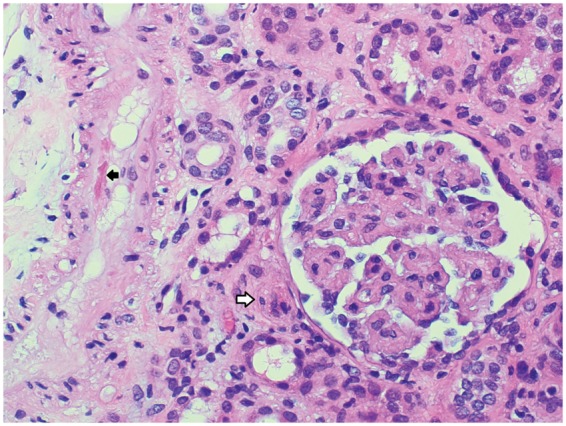

Given his elevated troponin and family history, he underwent a left heart catheterization and coronary angiography to evaluate for ischaemic heart disease. He had moderate, non-obstructive coronary artery disease. To evaluate for non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging was completed. The left ventricle had normal EDV of 163 mL (EDV index 86.7 mL/m2) with global hypokinesis, no regional wall motion abnormalities, and moderate systolic dysfunction (LVEF 38%). On T2 mapping, there was evidence of diffuse hyperintensity consistent with diffuse myocardial oedema or inflammation (Figure 4). No gadolinium contrast was used due to renal failure. Given concern for possible inflammatory aetiology, we pursued a cardiac biopsy. Pathology revealed an intramyocardial arteriole with obliterative changes and a few fragmented red blood cells within the subintimal space, suggestive of thrombotic microangiopathy (Figure 5A). There was no evidence of immune complex deposition or myocarditis. Electron microscopy demonstrated myocyte vacuolization and focal myofibrillar loss (Figure 5B). For heart failure management, he was started on carvedilol 6.25 mg twice daily and lisinopril 5 mg daily. Lisinopril was discontinued within 1 week due to symptomatic hypotension. The patient was maintained on eculizumab 1200 mg intravenously every 2 weeks.

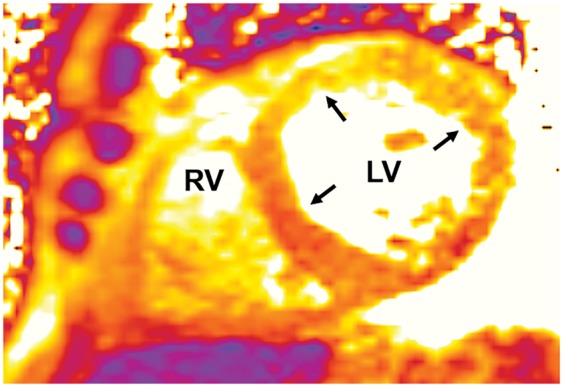

Figure 4.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: T2 signal consistent with diffuse myocardial oedema or inflammation (yellow–orange colour, indicated by black arrows) in left ventricle and right ventricle.

Figure 5.

Native heart biopsy (A) haematoxylin and eosin staining with arrow indicating arteriole suspicious for thrombotic microangiopathy with inset showing same arteriole at a different level with fragmented red blood cells. (B) Electron microscopy demonstrating focal myofibrillar loss, myofibrillar disarray, mild focal increase in the number of mitochondria, and small intracytoplasmic vacuoles.

On repeat echocardiogram 3 months later, the patient had complete recovery of his ejection fraction (60–65%) with no regional wall motion abnormalities (Figure 3C and D). He still had slight limitation to his physical activity due to dyspnoea, classified as New York Heart Association Class II. His single kidney did not recover enough function to discontinue dialysis.

Discussion

The aetiology of aHUS-associated heart failure is not well-understood. In this case of a patient with known aHUS and new-onset heart failure, we systematically evaluated for common heart failure causes with a heart catheterization, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, and then an endomyocardial biopsy. This process ruled out obstructive coronary disease, dilated cardiomyopathy, infiltrative cardiomyopathy, and inflammatory cardiomyopathies. Furthermore, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy diagnostic criteria were absent: ECG without diffuse ST-segment elevation and echocardiogram without regional wall motion abnormalities of basal hyperkinesis and apical akinesis. Our biopsy results suggested that thrombotic microangiopathy, like in the kidney, was the probable cause of aHUS-associated cardiomyopathy.

Cardiac microvascular thrombi leading to myocardial ischaemia has been suggested as general aetiology for patients with thrombotic angiopathies.3 One myocardial biopsy has been published in typical HUS-associated heart failure. The pathology was notable for myocyte hypertrophy, interstitial fibrosis, and some cytoplasm vacuolization—similar to our myocardial biopsy.4 We further show evidence suggesting thrombotic microangiopathy. No myocardial biopsy has been published from a patient with aHUS.

Since 2011, the FDA approved complement inhibitor eculizumab has been available—dramatically improving outcomes with many patients able to discontinue dialysis after weeks to months of therapy.5 Three cases in the literature report improvement of aHUS-related cardiac dysfunction after initiation of eculizumab. In two paediatric cases (18 and 19 months old), full recovery of left ventricular ejection was seen from 30% to ‘normal’ and from 45% to 71% after eculizumab therapy.6,7 In one published adult case, a 49-year-old woman with aHUS presented with acute renal failure and an ejection fraction of 20%.8 One month after eculizumab therapy was initiated, she had one readmission for decompensated heart failure. Her ejection fraction eventually improved to 40–45%.8 In contrast, our case demonstrates a complete recovery of left ventricular systolic function in an older gentleman after eculizumab therapy. Importantly, our patient did not have acute systolic heart failure at his initial presentation. His cardiomyopathy with diffuse global hypokinesis presented after a few weeks on eculizumab therapy suggesting ongoing aHUS injury. These two adult cases demonstrate that acute heart failure or heart failure decompensation can still occur during the early treatment phase of aHUS, but recovery does occur with ongoing therapy.

Conclusion

In this case report, we describe complete recovery of aHUS-associated heart failure after weeks of eculizumab therapy. For the first time, we show that the aetiology of aHUS-associated heart failure is likely from intramyocardial acute thrombotic microangiopathy as demonstrated by endomyocardial biopsy.

Lead author biography

Courtney M. Campbell, MD, PhD is a cardiovascular medicine fellow at the Ohio State University in the Physician Scientist Training Program. She studied History of Science at Harvard University, completing bachelor’s and master’s degrees. She earned her MD and PhD degrees from Vanderbilt University in the Medical Scientist Training Program. Her clinical and academic interests are in cardiac innervation, cardiac amyloidosis, and cardio-oncology.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal - Case Reports online.

Slide sets: A fully edited slide set detailing this case and suitable for local presentation is available online as Supplementary data.

Consent: The author/s confirm that written consent for submission and publication of this case report including image(s) and associated text has been obtained from the patient in line with COPE guidance.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Noris M, Remuzzi G.. Atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1676–1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Caprioli J, Noris M, Brioschi S, Pianetti G, Castelletti F, Bettinaglio P, Mele C, Bresin E, Cassis L, Gamba S, Porrati F, Bucchioni S, Monteferrante G, Fang CJ, Liszewski MK, Kavanagh D, Atkinson JP, Remuzzi G; International Registry of Recurrent and Familial HUS/TTP. Genetics of HUS: the impact of MCP, CFH, and IF mutations on clinical presentation, response to treatment, and outcome. Blood 2006;108:1267–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gami AS, Hayman SR, Grande JP, Garovic VD.. Incidence and prognosis of acute heart failure in the thrombotic microangiopathies. Am J Med 2005;118:544–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alexopoulou A, Dourakis SP, Zovoilis C, Agapitos E, Androulakis A, Filiotou A, Archimandritis AJ.. Dilated cardiomyopathy during the course of hemolytic uremic syndrome. Int J Hematol 2007;86:333–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Legendre CM, Licht C, Muus P, Greenbaum LA, Babu S, Bedrosian C, Bingham C, Cohen DJ, Delmas Y, Douglas K, Eitner F, Feldkamp T, Fouque D, Furman RR, Gaber O, Herthelius M, Hourmant M, Karpman D, Lebranchu Y, Mariat C, Menne J, Moulin B, Nurnberger J, Ogawa M, Remuzzi G, Richard T, Sberro-Soussan R, Severino B, Sheerin NS, Trivelli A, Zimmerhackl LB, Goodship T, Loirat C.. Terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N Engl J Med 2013;368:2169–2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Emirova K, Volokhina E, Tolstova E, van den Heuvel B.. Recovery of renal function after long-term dialysis and resolution of cardiomyopathy in a patient with aHUS receiving eculizumab. BMJ Case Rep 2016;2016:bcr2015213928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hu H, Nagra A, Haq MR, Gilbert RD.. Eculizumab in atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome with severe cardiac and neurological involvement. Pediatr Nephrol 2014;29:1103–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vaughn JL, Moore JM, Cataland SR.. Acute systolic heart failure associated with complement-mediated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Case Rep Hematol 2015;2015:327980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.