Abstract

This study examines the prevalence at which cancer survivors and their spouses/partners in the US stay at their jobs to maintain employer-based health insurance.

Many cancer survivors experience challenges related to employment, including limitations in ability to work.1 Given that most health insurance coverage for working-age individuals in the US is employer-based, a challenge is the inability to freely leave a job given limitations on health insurance portability, also called job lock.2 Job lock can negatively affect career trajectory and quality of life.3 Likewise, spouse/partner job lock can also affect family well-being.4 We examined job lock prevalence among cancer survivors and their spouses/partners and associated factors in the US.

Methods

This study identified cancer survivors who responded to questions about job lock (ever having stayed at a job out of concern for losing health insurance) from the 2011, 2016, and 2017 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Experiences With Cancer questionnaire. Separate multivariable logistic regression models examined the association of job lock in survivors and spouses/partners with self-reported survivor characteristics, including current age, sex, educational attainment, race/ethnicity, years since last cancer treatment, current marital status, comorbidities, and household income as a percentage of the federal poverty level (FPL). The study was determined to be exempt from institutional review by the National Cancer Institute. Weighted logistic regression modeling was used. P-values were determined to be significant at 0.05 (two-tailed test). Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines were used. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) and SAS-callable SUDAAN version 11.0.0 (RTI International).

Results

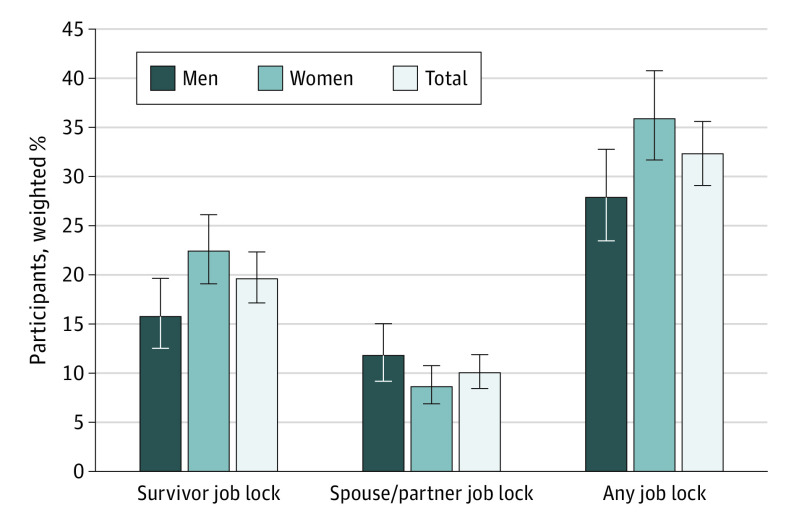

Of 1340 survivors, 526 (42.2%) were men and 814 (57.8%) were women. There were 365 respondents (26.1%) between the ages of 18 and 54 years, 387 (29.6%) between 55 and 64 years, 389 (30.1%) between 65 and 74 years, and 199 (14.4%) older than 75 years. Of 1340 surveyed cancer survivors overall, 266 (19.6%) (95% CI, 17.1%-22.3%) reported job lock. Of 1593 partners of survivors, 677 (44.4%) were men and 916 (55.6%) were women. There were 320 (18.9%) respondents between the ages of 18 and 54 years, 372 (24.0%) between 55 and 64 years, 475 (31.2%) between 65 and 74 years, and 426 (25.9%) older than 75 years. Of 1593 spouses/partners surveyed, 171 (10.7%) (95% CI, 8.4%-11.9%) reported job lock. Of 1094 respondents, 374 (32.3%) (95% CI, 29.1%-35.6%) reported any job lock for either themselves or their spouse/partner. Of 628 women, 235 (35.9%) (95% CI, 31.7%-40.3%, 235/628) reported any job lock and of 466 men, 139 (27.9%) (95% CI, 23.5%-32.8%) reported any job lock (Figure).

Figure. Prevalence of Job Lock in Cancer Survivors and Their Spouses/Partners.

Data were taken from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Experiences With Cancer questionnaire Full Year Consolidated Files, for 2011, 2016, and 2017. Survivor job lock percentage based on 1340 respondents, spouse/partner job lock percentage based on 1593 respondents, and any job lock percentage based on a total of 1094 respondents with complete responses to both questions on the survey. The error bars represent 95% CIs.

Characteristics significantly associated with survivor job lock included younger age and earning income between 138% and 400% of the FPL (Table). Spouse/partner job lock was more common among survivors who were women vs men (12% vs 8%), married vs unmarried (11% vs 7%), and nonwhite vs non-Hispanic white (16% vs 9%). Survivors with 3 or more vs no comorbidities were more likely to report spouse/partner job lock (14% vs 6%). Younger survivors (under 75 years) were more likely to report spouse/partner job lock, as were those earning between 138% and 400% of the FPL.

Table. Cancer Survivor–Reported Factors Associated With Job Lock for Cancer Survivors or Their Families.

| Characteristic | Job lock | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survivor (n = 1340)a | Spouse/partner (n = 1593)b | |||||

| Weighted % | Adjusted predicted marginal % (95% CI) | Wald P valuec | Weighted % | Adjusted predicted marginal % (95% CI) | Wald P valuec | |

| Time since last cancer treatment, y | ||||||

| ≥5 | 9.8 | 17 (11-26) | .75 | 10.6 | 4 (2-10) | .07 |

| 3-5 | 51.9 | 19 (16-23) | 48.7 | 11 (9-14) | ||

| 1-2 | 18.2 | 22 (17-28) | 19.4 | 8 (5-12) | ||

| <1 | 20.1 | 20 (15-25) | 21.4 | 12 (8-16) | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 42.2 | 17 (14-22) | .14 | 44.4 | 12 (1-16) | .03 |

| Female | 57.8 | 21 (18-25) | 55.6 | 8 (7-10) | ||

| Current age, y | ||||||

| ≥75 | 14.4 | 4 (2-9) | <.001 | 25.9 | 3 (1-5) | <.001 |

| 65-74 | 30.1 | 17 (13-21) | 31.2 | 9 (6-12) | ||

| 55-64 | 29.6 | 24 (19-29) | 24.0 | 15 (12-2) | ||

| 18-54 | 26.1 | 28 (22-35) | 18.9 | 19 (14-25) | ||

| Current marital status | ||||||

| Not married | 61.0 | 18 (15-21) | .09 | 68.2 | 7 (5-10) | .02 |

| Married | 39.0 | 23 (19-27) | 31.8 | 11 (9-14) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 82.1 | 20 (17-23) | .69 | 83.2 | 9 (7-11) | <.001 |

| Nonwhite | 17.9 | 19 (14-25) | 16.8 | 16 (12-22) | ||

| Educational attainment | ||||||

| <High school | 7.3 | 12 (7-19) | .09 | 11.4 | 9 (6-14) | .73 |

| High school graduate | 24.2 | 18 (14-24) | 28.8 | 9 (7-13) | ||

| >High school | 68.6 | 21 (18-24) | 59.8 | 11 (9-13) | ||

| Current income as a % of the federal poverty level | ||||||

| <138 | 11.4 | 17 (12-24) | .003 | 13.7 | 8 (5-12) | <.001 |

| 138-≤400 | 32.3 | 28 (23-33) | 34.6 | 15 (12-19) | ||

| >400 | 56.3 | 16 (13-19) | 51.7 | 8 (6-10) | ||

| Current No. of MEPS priority conditions other than cancer | ||||||

| 0 | 15.2 | 16 (11-21) | .48 | 12.8 | 6 (4-9) | .003 |

| 1 | 22.9 | 21 (16-27) | 19.2 | 10 (7-15) | ||

| 2 | 23.3 | 20 (15-25) | 21.4 | 7 (4-11) | ||

| >3 | 38.6 | 21 (17-26) | 46.7 | 14 (10-17) | ||

| Survey year | ||||||

| 2011 | 28.2 | 17 (14-21) | .17 | 28.2 | 12 (9-15) | .13 |

| 2016-2017 | 34.3, 37.4 | 21 (17-24) | 36.0, 35.9 | 9 (8-11) | ||

Abbreviation: MEPS, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

Participants reporting a history of only nonmelanoma skin cancer or skin cancer of unknown type were excluded (n = 481). Estimates incorporate national survey sampling weights.

In 2011, 2016, and 2017, 339, 331, and 190 participants, respectively, responded “does not apply” to the question about a spouse/partner staying at a job out of concern for losing health insurance for the family. Those responses are excluded here from the totals. “Does not apply” was not a survey option for cancer survivors; it was only in reference to spouses/partners, presumably as an option they could select if they did not have a spouse/partner during the reference period.

Statistical significance for all analyses was set at P < .05, and all tests were 2-sided.

Discussion

In this study, approximately 1 in 3 cancer survivors in the US reported job lock for themselves or their spouses/partners, suggesting that job lock is common and has implications for the well-being and careers of both survivors and their families. Given higher prevalence of job lock among younger survivors and those with incomes near the poverty level, it is important to note that those earning between 138% and 400% of the FPL are ineligible for Medicaid and may have fewer employment alternatives with comprehensive health benefits. Clinicians, social workers, and navigators have opportunities to identify job lock and other employment concerns throughout treatment/survivorship care and connect survivors with employment and health insurance counseling.5

One long-term study of childhood cancer survivors from 20186 found that 23% of survivors reported job lock. The present study demonstrates consistent findings in a nationally representative population of adult cancer survivors and also provides data on the prevalence of spousal/partner job lock. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act eliminated preexisting condition exclusions and created Marketplace exchanges for purchasing insurance coverage outside of work; whether these provisions will reduce job lock over time is unknown.

Study limitations include the cross-sectional design, lack of a control group, self-report of measures, and lack of information on cancer stage or course of treatment. Response rates ranged from 44% to 55%, comparable with other national household surveys. Sample weights help address nonresponse. Study strengths include it being a large, nationally representative sample and assessment of job lock experiences.

The present study found that 32% of cancer survivors reported job lock in either themselves or their spouses/partners. Additional research, particularly prospective, longitudinal, and qualitative studies, can help elucidate downstream consequences that may vary by sex and develop interventions to increase availability of insurance coverage regardless of employment.

References

- 1.Mehnert A. Employment and work-related issues in cancer survivors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;77(2):109-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rashad I, Sarpong E. Employer-provided health insurance and the incidence of job lock: a literature review and empirical test. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2008;8(6):583-591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stengård J, Bernhard-Oettel C, Berntson E, Leineweber C, Aronsson G. Stuck in a job: being “locked-in” or at risk of becoming locked-in at the workplace and well-being over time. Work Stress. 2016;30(2):152-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Repetti R, Wang SW. Effects of job stress on family relationships. Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;13:15-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Moor JS, Alfano CM, Kent EE, et al. Recommendations for research and practice to improve work outcomes among cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(10):1041-1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirchhoff AC, Nipp R, Warner EL, et al. “Job lock” among long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(5):707-711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]