Abstract

Despite the plethora of published studies on intracranial aneurysms (IAs) hemodynamic using computational fluid dynamics (CFD), limited progress has been made towards understanding the complex physics and biology underlying IA pathophysiology. Guided by 1733 published papers, we review and discuss the contemporary IA hemodynamics paradigm established through two decades of IA CFD simulations. We have traced the historical origins of simplified CFD models which impede the progress of comprehending IA pathology. We also delve into the debate concerning the Newtonian fluid assumption used to represent blood flow computationally. We evidently demonstrate that the Newtonian assumption, used in almost 90% of studies, might be insufficient to describe IA hemodynamics. In addition, some fundamental properties of the Navier–Stokes equation are revisited in supplementary material to highlight some widely spread misconceptions regarding wall shear stress (WSS) and its derivatives. Conclusively, our study draws a roadmap for next-generation IA CFD models to help researchers investigate the pathophysiology of IAs.

Keywords: Cerebral aneurysm, cerebrovascular blood flow, CFD, fluid dynamics, non-Newtonian fluids

Introduction

With 50–60% mortality after rupture and 30–40% dependence rate amongst survivors,1 intracranial aneurysms (IAs) are one of the most feared cerebrovascular pathologies. While treatment options are very well established in the medical field, either in the form of surgical clipping, with its modifications based on the location, geometry, complexity, etc., or endovascular treatment with its various forms,2,3 there exists a dilemma that is yet to be solved. Approximately 50–80% of IAs do not rupture in the individual's lifetime.4 While it is the standard to treat all ruptured aneurysm cases upon detection,3 unruptured aneurysms make up for a difficult decision making. Unruptured aneurysms can be followed for certain period of time, especially smaller sized ones.5 However, while changes in aneurysm morphology or size are warning signs against impending rupture, there is no telling how fast such changes will occur6–8 and treating unruptured aneurysms is certainly not a risk-free option.9–11 Therefore, taking chances in IA care do not only risk the livelihood of patients, but it also multiplies the cost of healthcare delivery as well as burden of the healthcare services.12 Given the aforementioned factors, the cerebrovascular research into IA pathobiology needs not only to answer questions regarding the formation and growth of IAs, but also seeks to answer why and how aneurysms rupture. A question that may seem direct at the first glance, yet it is made complex by the intertwining relationships between biological and physical factors that are yet to be fully understood.

Therefore, to understand the pathobiology of IAs, it is imperative to understand the different flow regimes in the intracranial vessels and inside the IAs and how they affect the ECs and consequently the vessel wall. To understand the blood flow dynamics, researchers had to turn to the field of fluid mechanics, modifying their tools to be used for the study of blood flow in various vessels, connecting the dots and ultimately searching for a holistic understanding of the pathology of IAs. The most famous and ubiquitous of these tools used nowadays is computational fluid dynamics (CFD) analysis.

It is a very well established fact that endothelial cells (ECs) sense the blood flow via a variety of cell surface and intracellular mechano-sensors,13 and they transmit signals of the blood flow into cellular response that derives the vascular homeostasis.13,14 Any abnormality in the blood flow induces pathologic responses in the ECs, causing vascular diseases such as atherosclerosis.15–17 ECs also were shown to transmit flow signals to the underlying cells in the vascular wall, such as vascular smooth muscle cells, via exosomes and microRNA transfer.17 Moreover, ECs were shown to respond to wall shear stress (WSS) via several mechanobiological mechanisms.18,19 From such observation, it is safe to base the model of IAs formation, growth and rupture on an interaction between blood flow and ECs. Even in ruptured aneurysms where the ECs are lacking,20 such a finding must be linked with ECs death and shedding, possibly leading to an accelerated aneurysmal wall weakening and eventual rupture from the loss of the normal buffer between the flow and the wall (i.e. the ECs and their intercellular junctions15,21,22). ECs damage is associated with internal elastic lamina pathophysiologic changes and damage, as well as inflammatory cell recruitment, via cytokines and other molecules, and aneurysm wall degeneration or sclerosis.23,24 Moreover, abnormal collagen fibers in the aneurysm wall indicate a failed wall remodeling.25 Indeed, differences in wall inflammation and internal elastic lamina were observed between ruptured and unruptured aneurysms.24 This indicates that the pathophysiology of IA, while might start at the level of ECs, is in fact spanning all the layers of the wall and should be studied with this in mind.

Early works on IA hemodynamics

There is almost a consensus in literature on the prime role of wall shear stress (WSS) as the most profound hemodynamic parameter affecting aneurysm fate. Such consensus was established following to the early work of Ferguson et al.26–28 in the early 1970s, in which they constructed in vitro flow models of IA geometries guided by craniotomy observations. Their work was revolutionary at the time as they suggested that transition to turbulence occurs in IA and lead to degeneration of internal elastic lamina and rapid weakening of the aneurysm wall.27 Their work was followed by a series of studies by Steiger et al.,29 Liepsch et al.,30 Gonzalez et al.31 and Kim et al.32 which settled the consensual WSS theory in IA hemodynamics.33 Steiger's group work was the first recorded in vitro measurements of IA flow fields using laser techniques.34,35 Until that time in the late 1970s to early-mid 1980s, in vitro works postulated that blood flow in IA exhibits turbulence and transitional features which contribute to the IA growth and wall deterioration,26,36,37 which is in line with recent biological findings.15 Moreover, such early works considered the non-Newtonian effects of IA hemodynamics influential.34,38–40 Wall shear stress in these studies was only a measure of the flow at the IA wall, not an independent variable that thought to control IA pathophysiology and mechanotransduction.

CFD and current controversies

In the past two decades, CFD has been an effective research tool for investigating numerous aspects of IA,10,41–43 most importantly growth and rupture mechanisms and their relation with vascular hemodynamics.44–46 IA CFD simulations mostly aim to evaluate the morphologic factors and hemodynamic forces on the aneurysm walls47 which trigger a set of vascular remodeling mechanisms48,49 leading to IA progression and possible rupture.50 Moreover, CFD is used to study the growth and rupture of IAs, as well as assessing different endovascular treatment modalities51 and validating new endovascular devices.8,10,11 While CFD and flow studies have significantly improved our understanding of vascular pathologies such as atherosclerosis and that the flow perturbations at bifurcations were linked to evident pathobiological processes,15,52 such an understanding is yet to be reached in the field of IAs research, and a large gap of knowledge still exist. This gap of knowledge is in part due to the complexity of blood flow in IAs as well as controversies regarding the actual flow regime causing rupture.10,53 These controversies are related to the actual inducer of aneurysm rupture, whether it is high or low WSS54 and to the actual viscosity model that should be adopted to model the blood flow, whether Newtonian or non-Newtonian.55 Moreover, there are controversial issues pertaining to the validity of the some of the parameters used in the analysis of the flow regimes, such as the vector calculations of WSS, that need to be addressed.56 Thus, we believe it is vital to evaluate the tools we are using to understand IAs, highlighting the controversies and unveiling the shortcomings in our approaches and tools to be able to progress and improve.

The optimality principle, proposed by Murray,57 which is often used in CFD simulations, correlates arterial hemodynamics to the dimensions of individual arteries via a power-law correlation. The major consequence of such principle is that any vascular remodeling due to hemodynamic changes should eventually be attributed to deviation from the optimal geometrical parameters. However, Murray's principle was derived assuming steady laminar flow in straight vessels, and no direct communication between arteries of the same rank. This is not the case in the circle of Willis or any intracranial vessel.58 In vivo evidence showed that Murray's law could be valid on the scale of the system; however, it is incapable of accurately predicting in vivo WSS measurements in intracranial arteries.59–61 This leaves the coupled interaction between IA and hemodynamics, on different scales, an open question beyond any geometrical characterization attempts. Consequently, this coupled interaction inherits multi-layered complexity from the morphological sophistication of the circle of Willis,62 let alone the fluid dynamics intricacies driven by the multi-harmonic blood flow waveform which exhibits phase shifts,63,64 non-linear dynamics,65 and a multitude of biochemical, biophysical and mechanobiological processes.66

Aim and motivation

The aim of this work was to evaluate the current stand-point of the CFD research on IAs by performing a meta-analysis of all the literature concerning IA hemodynamics and critically reviewing it. The ultimate aim is to evaluate the tools and techniques used in order to provide a recipe for improvement. Such an improvement will enhance the outcome of CFD research and provide a better link between the physics of the blood flow and the biological processes observed in the IAs. Through our meta-analysis, we came across several open-ended questions that we will try to either answer or highlight and present to the readers. These questions include:

What are the current trends in IA hemodynamics research?

Does the Newtonian assumption, widely used in CFD models, accurately represent physiological conditions?

What is the actual flow regime of blood in intracranial aneurysm?

In the light of current controversies in CFD literature, what is the clinical and biological relevance of such models with respect to the initiation, growth and rupture of intracranial aneurysm?

We aim to tackle these questions based on the contemporary paradigm driven from published studies in the field. The final target of this meta-analysis and critical review is to stimulate debate, critical analysis and falsification of such paradigm to advance IA CFD models towards future theoretical and applied relevance.

Methods and data

Meta-analysis on IA CFD studies

We obtained the literature records and references from Scopus bibliographic database using TITLE-ABS-KEY search function with the following search terms:

– “Cerebral aneurysm” OR “Intracranial aneurysm”

– AND “Hemodynamics” OR “Flow dynamics” OR “Blood flow”

Then we classified the references corpus, which contained 1733 published articles, manually through reading the abstracts and conclusions and grouping the articles into groups based on the technique of study (CFD or other techniques including in vivo, in vitro studies and animal models). Then, the CFD references, which counted 795 papers were analyzed in detail for technique, methods and models used. All the references obtained from the meta-analysis search records were classified according to their relevance to the topic of this study. The details and findings of such classification and analysis are presented in the Results and Discussion section. The meta-analysis was conduced in line with the PRISMA guidelines.67

Meta-analysis criteria and mathematical model for WSS comparison

Literature records have been searched on Scopus® database for studies reporting the dimensions and flow rates or velocities of intracranial and cerebral arteries in healthy subjects. Patients suffering from intracranial aneurysm are not necessarily suffering from other disorders that could alter their blood viscosity. In addition, blood flow velocity inside aneurysms is often much less than such of the parent artery. Hence, it is valid to assume that the blood viscosity behavior in aneurysm patients is similar to such in healthy patients for the scope of the present study. The studies were selected such that each study provide synchronized readings for the blood velocity (m/s) or flow rate (m3/s) with the vessel diameter (m) or cross-sectional area (m2) during specific instants of the cardiac cycles or as mean values for one cardiac cycle. The details of such studies are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. A summary of the measurements is plotted in Supplementary Figure 1. The collected measurements from selected studies were used to compute the shear rate (s−1) based on the exact Hagen-Poiseuille solution of Newtonian incompressible flow68–70 as following

| (1) |

| (2) |

For shear thinning fluids, where velocity profiles deviate from the parabolic profile shown by the Hagen-Poiseuille solution, shear rate values should be corrected using the Weissenberg–Rabinowitsch (W-R) shear-thinning correction71,72

| (3) |

where n is the shear-thinning index of the fluid, as presented by the rheological model that is used to compute the non-Newtonian viscosity. Hence, wall shear stress (WSS) was calculated for the Newtonian viscosity assumption as

| (4) |

and for different non-Newtonian models as

| (5) |

where is the effective viscosity as calculated from each of the non-Newtonian models

Power-law (PL)73:

| (6) |

where and .

| (7) |

where = 0.00345 Pa.s, = 0.056 Pa.s, λ = 3.313 s and n = 0.3568.

Carreau-Yasuda (C-Y)77:

| (8) |

where = 0.0022 Pa.s, = 0.022 Pa.s, λ = 0.11 s, a = 0.644 and n = 0.392.

| (9) |

where , . The Casson yield stress is considered here proximal to the shear-thinning index of blood.80

Cross (CR)81:

| (10) |

where = 0.0036 Pa.s, = 0.126 Pa.s, λ = 8.2 s and n = 0.64.

Hypothesis testing and statistical analysis

The null hypothesis of the WSS comparative study was that the Newtonian and non-Newtonian calculations of WSS are similar with no significant differences. This is the essence of using Newtonian viscosity in CFD simulations. Paired t-tests were conducted to compare the Newtonian (N) model with each of the five non-Newtonian rheological models that are commonly used in literature, given by equations (6) to (10).

In vivo calculations of WSS in IAs

The validation of CFD models against in vivo measurements is a crucial task, yet not commonly practiced in the IA hemodynamics research community. Here, we explored the studies which reported in vivo estimations of WSS in IA. In principle, different radiological techniques such as MRI or transcranial color Doppler (TCCD) are used to measure the velocity time-series in the region of interest. Then, post-measurement calculations are conducted to estimate WSS as function of the measured velocity series and geometry. A comparative analysis based on six studies, as summarized in Table 2, which reported in vivo post-measurement calculations of WSS in IAs was conducted. The criteria for selecting the six studies were as following:

– Usage of high-fidelity multidimensional radiological technique (3D/4D MR)

– Study must report quantitative and qualitative results

– The method of computing WSS sufficiently explained in each study in terms of adequate use of measurements data and fully explained mathematical model.

Table 2.

Summary of in vivo estimations of hemodynamic parameters in IA.

| Reference | WSSrel (%) | WSSIA (Pa) | Usys (m/s) | (1/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meckel et al.234 | 24.6–116.6 | – | 0.06–0.59 | – |

| Isoda et al.235 | 46.9–76.4 | 1.16–2.22 | 0.0–0.5 | 0.0–1600 |

| Schnell et al.236 | – | 0.5–2.25 | 0.4–1.01 | – |

| Blankena et al.237 | – | 0.1–8.1 | – | – |

| Zhang et al.238 | – | 0.63–1.09 | – | – |

| Boussel et al.239 | – | 0.01–0.2 | 0.0–0.1 | – |

Note: WSSrel is the ratio between average WSS in the aneurysm and parent artery, respectively, while WSSIA is the average value of WSS in IA. Uavg is the spatial range of maximum velocity inside the aneurysm per study and is the range of shear rate inside the aneurysm per study.

The values of WSS presented in such studies are reviewed and analyzed. The purpose of this analysis is to explore the hemodynamics of IA as detected in vivo to provide benchmark to discuss the current hypothesis proposed by CFD studies.

Results and discussion

CFD and deviation towards simplification

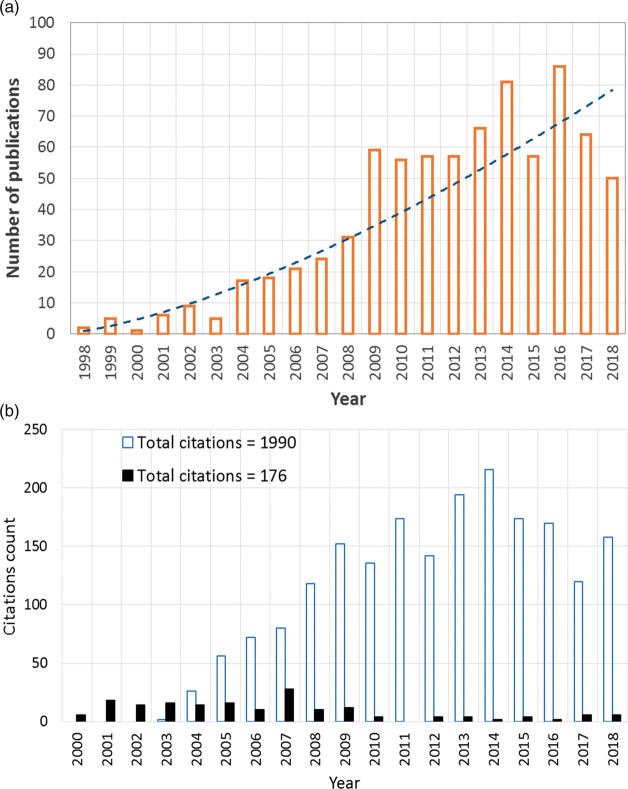

In the 1990s, and with the large leap in CPU speed and radical increase in PC availability, CFD has emerged as a research tool to investigate IA hemodynamics.82,83 Figure 1(a) shows the trend of using CFD as a research tool in cerebral aneurysm hemodynamics based on Scopus® database. Nevertheless, IA CFD simulations, attempting to provide clinically relevant analyses, had adopted assumptions far from the experience of the earlier in vitro works. Now, the highest citations of CFD studies goes to works that have assumed Newtonian blood viscosity84,85 and laminar flow with no transition to turbulence.86–88 Figure 1(b) shows a comparison between the citations of early in vitro laser measurements encompassing complex physics (i.e. non-Newtonian effects, transition to turbulence) compared with the early CFD works with simplified physical assumptions (i.e. Newtonian viscosity, laminar flow). As a result of such relaxed assumptions in early CFD simulations, the argument favoring the role of high WSS in aneurysm rupture84,89 challenged an opposing argument correlating low WSS with IA wall disintegration and degeneration leading to rupture.85,90–92 While in some other CFD studies, low93 as well as high94 WSS were controversially correlated to the growth of IA. Several articles95–99 have highlighted such controversies along the past two decades and discussed the discrepancy of findings, however without providing enough reasoning to their root causes. The recent works of Can et al.,100 Zhou et al.,101 and Meng et al.102 are exemplary endeavors to find coherence among the large IA CFD corpus, however, without definitive and conclusive findings, especially with relevance to IA mechanobiology and clinical applications.

Figure 1.

The rise of simplified CFD models of IA hemodynamics during the past two decades. (a) Exponential growth in the use of CFD as a research tool in aneurysm hemodynamics based on Scopus® database. Search query available in the supplementary materials. (b) Comparison of the citation counts (2000–2018) from Scopus® bibliographic database between the early in vitro works reporting complex IA flow physics (black column indicates total annual citations for references34,38,39) and subsequent CFD models adopting simplified assumed flow physics (blue outlined column indicates total annual citations of references85,87,234).

In addition to the attempts of unfolding the physics of IA hemodynamics using CFD, CFD has been a very useful tool in the design, development, and evaluation of endovascular management methods. The term virtual stenting has attracted many research groups around the world to empower endovascular management with CFD decision-making tools.103–106 Adopting simplified flow physics as the mainstream IA CFD works, many research groups have evaluated the embolization efficacy of flow diverters and stents107,108 and IAs endovascular coiling.11 In the matter of fact, much of the development in endovascular devices can be attributed to the availability of CFD as an optimization tool for the design, testing and synthesis of such devices. However, the incomplete understanding of complex blood flow dynamics has maintained the concept of such devices with minimal progress along the years. Devices used to treat IAs depend on one concept: flow isolation.109–112 Stents, coils and flow diverters aim at isolating the aneurysm cavity from the main flow, hence allowing ECs to recover and the vascular wall to heal. In addition to the design complexity of such devices,113,114 their efficacy depends on IA geometry, morphology, location and other inherent factors of the IA.115,116 It can safely be argued that a better understanding of IA hemodynamics, and blood dynamics at large, is necessary to radically improve the current design theory of endovascular devices.

Linking hemodynamics to IA mechanobiology

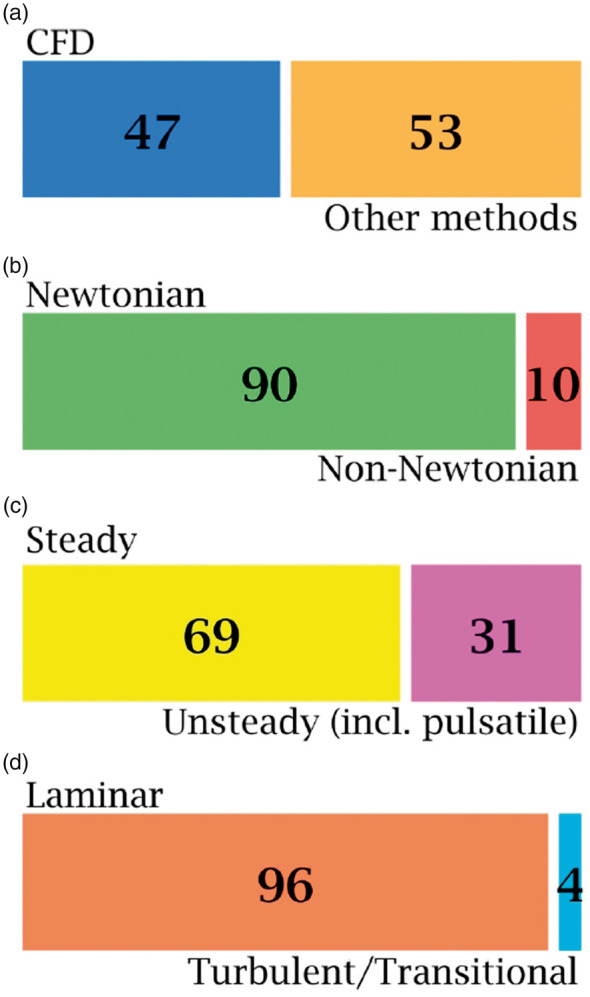

Well-established in vitro studies of endothelial cells response to WSS, which is relevant to IA mechanobiology,117 depend on the Newtonian assumption.118–120 In such studies, EC cultures are subjected to different levels and regimes of WSS, created by simple Poiseuille-type Newtonian fluid flow,119,121–123 to investigate the cells response to each WSS level and regime. It has been established, through the vast majority of these studies, that endothelial dysfunction (ED) associated with cerebral aneurysm occurs under WSS regime which can be best classified under disturbed/turbulent flow rather than uniform/laminar flow.118,124–126 Chiu and Shien118 showed that low values of WSS, often associated with distrubed/turbulent flow, are associated with long-term ED and remodeling processes similar to those encountered in IA growth. In a comprehensive and extensive meta-analysis, Zhou et al.127 has also showed that IA rupture is often associated with low WSS values inside the aneurysm. Now, it has been established that EC respond to laminar flow by supressing pro-inflammatory transcription agents and respond to distrubed (i.e. turbulent-like) flow by upregulating inflammatory and chemotactic mediators.128 However, these findings have not been reflected on the published CFD studies of IA hemodynamics, as shown in Figure 3(c) and (d) and discussed in the next section, such that only 31% of the studies considered the pulsatile nature of blood flow, while 4% of such studies attempted to explore turbulent-like structure that might exist in IA hemodynamics, as referred to from EC research.

Figure 3.

Classification of published studies on intracranial anereurysm hemodynamics with respect to physical assumptions in the CFD models, as revealed by Scopus® bibliographic databases. A total number of 1733 publications was found by searching Scopus® on 14 October 2018. This classification was conducted using sequential searches via Scopus® analytic tools. Classification methodology is explained in the methods section. Articles using CFD as a method of investigation comprised 47% of the literature on aneurysm hemodynamics (a). Of these CFD-based articles, only 10% used the non-Newtonian viscocity assumption to investigate aneurysm hemodynamic features (b), 31% used unsteady and pulsatile models (c) and only 4% investigated turbulence and transition to turbulence (d).

Classification of IA CFD models

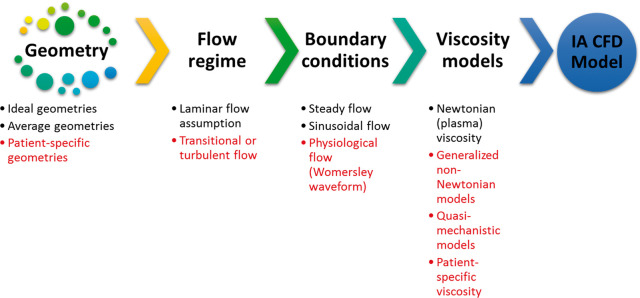

CFD models of IA can be generally classified according to the level of complexity to two major categories: ideal and patient-specific models. Figure 2 shows a schematic of the different parameters determining the level of IA CFD model complexity, as explained henceforth. Ideal models are often based on assumed geometry with anatomically relevant dimensions used to study the morphological patterns129–133 and Neuroendovascular device efficacy.134,135 Some of the ideal model geometries are actually constructed from averaging of patient-specific dimensions across a specific population to compare the relevance of gender,136 morphology137 or complex cases of IA.138 Patient-specific models are often constructed from DSA images,139 and then converted to volume meshing suitable for any adequate CFD solver.41 The discretization of the reconstructed 3D models into computational grid dictates the flow regime and limits the underlying physics in the solution. If the computational grid and time marching scheme are sufficiently accurate, it would be possible to capture the flow specific physics taking place at higher frequencies140 such as flow instabilities141,142 or transition.143,144 It is also essential to define the solution method, boundary conditions, and the viscosity model to solve the Navier-Stokes equations (NSE) for the blood flow in the aneurysm geometry of interest. There are three main methods for solving NSE numerically for IA blood flow scenarios: the generic finite volume method,145 adapted finite element methods,146–148 or the lattice Boltzmann method149–151 which was recently introduced to the field after success in other numerous applications. The boundary conditions required by any NSE solver for an IA CFD simulation are either steady, pulsatile (i.e. sinusoidal) or Womersley waveform. Steady flow boundary conditions are usually used to provide qualitative assessment of the aneurysm flow field and WSS;152 however, they are considered to be a form of idealization even if used with patient-specific geometries as they neglect some of the main phenomena in aneurysm hemodynamics and reduce the clinical relevance of the CFD models.153–155

Figure 2.

The parameters and assumptions which define the complexity of CFD models. The meshing resolution of the flow domain, boundary conditions as well as the viscosity models and solver numerical settings define the flow physics predicted by the CFD model and whether or not it could model transitional and turbulent features of the flow.

As to the blood viscosity models, the majority of IA CFD simulations have adopted Newtonian viscosity assumption when solving the NSE for either steady or pulsatile flows.10,45,75,84,156,157 Bibliographic meta-analysis from Scopus® database revealed interesting insights about the current paradigm of IA CFD models. The most important aspects of any IA CFD model are the viscosity, transient nature, and flow regime as resolved by the computational grid. Figure 3 summarizes such aspects as revealed by surveying the IA hemodynamics literature. It was found that 47% of published literature studying IA hemodynamics was based on CFD models, while the remaining 53% was shared by in vitro, in vivo, pathological and other research methods in the field. Only 10% of the published CFD studies to date have considered the non-Newtonian viscosity of blood in modelling intracranial aneurysm hemodynamics. In fact, most of the former studies relied on the assumption that blood viscosity follows a Newtonian behavior in cerebral arteries since the shear rates are presumed to be higher than the range required for the non-Newtonian properties to become effective.158–161 Tracing the origins of such assumption was quite difficult, and a considerable number of the highly cited studies in the field have not discussed such assumption in details,87,162,163 or just refer to the parent artery of the aneurysm to be large enough to neglect the non-Newtonian properties of blood.164,165 While some other studies have arbitrarily used this assumption with some sort of basic physical reasoning,84,166 some studies simply cite classic publications on erythrocytes167,168 or plasma169,170 viscosity to be dominantly Newtonian in in vitro measurements, hence, justifying the use of their values in complex in silico CFD simulations.

Hemodynamic instabilities and transitional features of aneurysmal flow

In the past few years, some Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS) studies171–173 were conducted to provide detailed physical insight onto aneurysm hemodynamics. Such studies were performed using the Newtonian viscosity assumption. According to these studies, blood flow in cerebral and intracranial aneurysms exhibits turbulent-like structures and shows subcritical transitional behavior (Reynolds < 103, Womersley < 10) which was shown by monitoring the power spectrum of the velocity time-series at different locations of patient-specific aneurysms. Another study, by the same research group, reported patient-specific CFD simulations of intracranial aneurysm hemodynamics to examine the impact of a non-Newtonian viscosity model in comparison to the effect of solution methods on the results of WSS and Oscillatory Shear Index (OSI).174 The simulation results, deemed to represent a DNS solution, showed that the impact of non-Newtonian assumption is insignificant in comparison to the impact of solution methods. However, the study has not provided sufficient information on the impact of non-Newtonian viscosity on the turbulence-like structures found in aneurysmal flow as reported previously by the same group of researchers.171–173 It is well known that non-Newtonian shear thinning fluids, such as blood, are more asymptotically and monotonically stable than Newtonian fluids, such that subcritical transition to turbulence becomes unlikely to take place.175–177

The credibility of the DNS results comes from the fact that in DNS, the Navier-Stokes equation is solved to the highest possible resolution of length and time scales.178,179 Beside its theoretical rigor,180 DNS has been reproducibly validated in numerous works.181,182 On the other hand, in commonly used CFD solvers and settings among the community, only the laminar scales are resolved. Hence, the latter solvers dictate in priori simplified physics in the solution. Therefore, and despite their expensive computational cost, DNS solvers have been extensively used for four decades in all areas of fluid dynamics research,183–185 except in hemodynamics until recently.186 In DNS settings, the smallest grid cell in the fluid domain should be smaller than the smallest vortex in the flow. The total number of grid cells is often proportional to for fully developed turbulent flow.187 This increases the computational cost of DNS significantly. Rigorous conditions are also applied on the time-marching technique to ensure capturing of the smallest time scale. Vascular blood flow has a multiharmonic pulsatile nature which covers a relatively wide range of length and time scales. In addition, the complex vascular morphology provides perfect conditions to drive the flow towards instability and transition. Therefore, DNS by definition is the best and most reliable method to study vascular blood flow at large, and aneurysm hemodynamics specifically.

It must be noted that the classical theory of hydrodynamic stability has been established to study steady flows subjected to finite perturbations in space and time.188 The physics underlying transition to turbulence in viscous incompressible flow, as in simple geometries such as straight pipes or under shear conditions, remains in question until today.189–192 Previous investigations of transition to turbulence in pulsatile pipe flow are limited and have not established a consensus regarding this critical condition.193–196 It must also be noted that most of such works considered monoharmonic pulsatile flow196 with very few works that aimed at discussing multiharmonic pulsatile flow which is the nature of the blood flow.197 Blood flow in IA exhibits several fluid dynamics phenomena depending on the morphology of parent and daughter arteries, as well as the size and location of the IA. Shear layers,198 precessing vortices,199,200 jet impingement,201,202 recirculation and separation zones203,204 are inherently found in IAs. IA hemodynamics, therefore, are quite different from pulsatile pipe flows investigated in literature for turbulence transition criteria.194–196,205,206 It is impossible to apply the criteria of laminar-turbulence transition, classically devised for flows in straight pipes, to characterize IA flows. Therefore, fundamental fluid dynamics research is needed to characterize the transition to turbulence in IA flow.

Non-Newtonian properties of intracranial blood flow

Here, we concisely reviewed the previous studies aimed at evaluating the significance of the Newtonian assumption on WSS predictions. It was shown that the use of Newtonian viscosity results in overpredictions of aneurysm wall shear stress (WSS)207 which could compromise rupture risk prediction (RRP) efficacy.208 Frolov et al.209 conducted in vitro comparative study between Newtonian and non-Newtonian blood surrogate fluids to investigate WSS distribution in patient-specific internal carotid artery aneurysm (ICAA) using 1D Laser Doppler Anemometry (LDA) with micrometer-scale spatial resolution. Their results showed that the use of Newtonian fluid over-predicts WSS by 11.7–19.7% at the aneurysm neck and dome, respectively. Hippelheuser et al.210 investigated the hemodynamics of 26 patient-specific cerebral aneurysm using Newtonian and non-Newtonian (Carreau) viscosity models. Their comparative analysis showed significant differences in time-averaged wall shear stress (TAWSS) between the Newtonian and Carreau models. Such difference impacts the predicted rupture criteria of the aneurysm via CFD. Sano et al.211 conducted comparative analysis on cerebral aneurysm hemodynamics using CFD. They used patient-specific viscosity data in comparison with the generalized Newtonian assumption. They found up to 25% difference in the normalized wall shear stress (NWSS) between the non-Newtonian and Newtonian simulations. They concluded that any rupture risk criteria, irrespective from aneurysm size, should be significantly affected by the viscosity model used in the CFD simulation. Otani et al.212 simulated the hemodynamics of a coiled patient-specific cerebral aneurysm using two viscosity models. They used the Carreau-Yasuda non-Newtonian model in comparison with the generalized Newtonian viscosity assumption. They evidently showed that the use of non-Newtonian viscosity model in CFD produces flow structure and hemodynamic parameters that are different from such produced by the Newtonian assumption. More specifically, they identified that the Newtonian assumption underestimates the low shear-rate regions which could possibly skip thrombus formation features in the aneurysm. Moreover, Xiang et al.,213 Morales et al.,214 and Owen et al.215 showed noteworthy differences between the Newtonian and various non-Newtonian blood viscosity models resulting in significant differences in predicted hemodynamics of intracranial aneurysm.

Newtonian vs non-Newtonian WSS calculation

Recently, we55 provided the first in vivo evidence of the large discrepancy between non-Newtonian and Newtonian blood viscosity assumptions in major cerebral arteries from Doppler ultrasound measurements. The following section employs somehow similar methodology,55 however, with measurements collected from a large pool of radiological studies using different techniques. The measurements and analytical solutions of the Hagen-Poiseuille and Weissenberg-Rabinowitsch equations are comparatively assessed using statistical paired t-tests to evaluate the null hypothesis representing the Newtonian assumption.

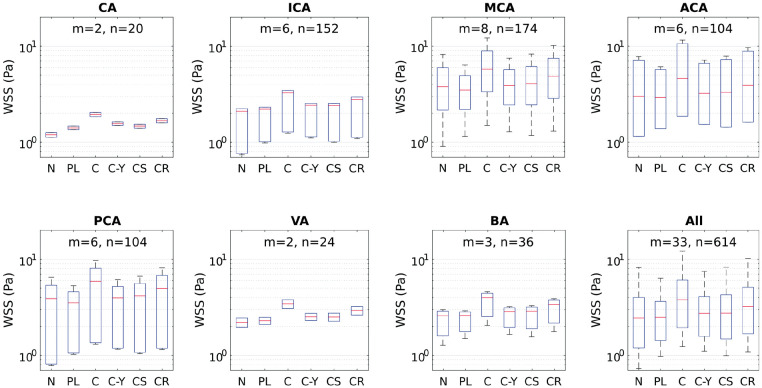

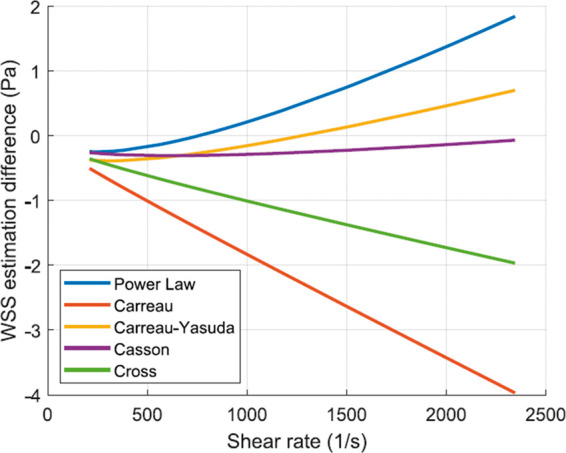

The calculations of WSS based on the mathematical model presented in methods section showed considerable variations between the Newtonian and non-Newtonian models, as shown in Figure 4. Different non-Newtonian models over-predict and under-predict Newtonian WSS by values corresponding to 2 and 4 Pa, respectively, as shown in Figure 5. The statistical t-test results presented in Table 1 show statistically significant differences between WSS calculation using Newtonian and different non-Newtonian models. In CFD calculations, the Weissenberg-Rabinowitsch (W-R) shear-thinning correction is not applied since the non-Newtonian closure of the shear stress term in Navier-Stokes equation is solved explicitly with the velocity equation. The coupling parameter is therefore the shear rate tensor. Here, the W-R correction is applied in order to ensure that the non-Newtonian calculations of WSS mimic such that from CFD simulations in terms of its proportionality with the Newtonian calculations. The W-R correction has been extensively verified and validated.216,217 Therefore, the statistical t-tests applied here represent meaningful comparison between WSS calculated from Newtonian and non-Newtonian models.

Figure 4.

Box plots of WSS as calculated by Newtonian and five different non-Newtonian models in different intracranial arteries which are known for harboring IAs. Box plots were computed using m means for a total of n measurements by artery. The red midline in the box plots represents the median of WSS per artery per model for all studies. Models compared: Newtonian (N), Power-law (PL), Carreau (C), Carreau-Yasuda (C-Y), Casson (CS) and Cross (CR).

Figure 5.

WSS estimation difference as calculated for different non-Newtonian models. Measurements of diameter and flow rate of different intracranial arteries as compiled from the meta-analysis with colors showing different arteries.

Table 1.

Hypothesis testing of the Newtonian assumption based on WSS calculations from in vivo radiological measurements.

| Model | Mean (Pa) ± Variance (Pa) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Newtonian | 3.073 ± 5.125 | ∞ |

| Power-law | 2.843 ± 2.690 | 0.046 |

| Carreau | 4.688 ± 10.985 | |

| Carreau-Yasuda | 3.214 ± 3.752 | 0.021 |

| Casson | 3.329 ± 4.867 | |

| Cross | 3.965 ± 7.573 |

Note: The sample population consists of the WSS values from all the arteries in the meta-analysis.

The range of WSS in IAs spans values that correspond to stagnant, creeping, and transitional flows. The order of magnitude of WSS, as depicted in Table 2 by in vivo methods, is between 10−2 and 10 Pa, depending on numerous factors including size, shape, morphology and location of IA. This range corresponds to shear rates in the order of 100 to 103 S−1. From such in vivo measurements, it is clear that blood flow inside the aneurysm manifests the non-Newtonian properties of blood. On the other hand, even in healthy intracranial arteries, the viscous behavior of blood shows considerable variation from the Newtonian simplification. This has been evidently proved from the meta-analysis calculations plotted in Figure 5. The wide range of values of shear rate and corresponding WSS in intracranial arteries clearly proves that the Newtonian assumption is inaccurate both qualitatively and quantitatively. This is quite evident from the hypothesis tests summarized in Table 1. All non-Newtonian models showed differences with the Newtonian model, with the most significant differences attributed to Carreau, Casson and Cross models. Figure 5 shows that Cross and Carreau models consistently produced WSS that were always higher than the Newtonian assumption. The remaining models produced both negative and positive differences showing varying response to different ranges of shear rate.

Is WSS enough to bridge hemodynamics and aneurysm pathology?

Choosing wall shear stress (WSS) as the discriminant variable to link blood flow (i.e. hemodynamics) to cellular response, hence physiological changes in blood vessels, was an arbitrary choice based on modest physical reasoning. Simply, early works chose WSS since it is the only parameter that depends on the flow (i.e. function of the near-wall shear rate) and shows multicomponent mechanical stress on the wall. Early researches in vascular biomechanics considered blood vessels as elastic or rigid tubes which respond mechanically to blood flow.218–221 The concept of mechanical response of arteries to blood flow propagated in literature and scientific community in the following decades.222,223 Following to the discovery of endothelial mechanosensors,224,225 it was found that endothelial cells respond to flow direction226,227 and local structures in disturbed flow.118,228 Flow with inherent vorticity field and vortex structures was found to affect endothelial cells differently than fully developed uniform flow.118 When any fluid dynamicist thinks of flow structures and directionality, a number of flow field variables arise, excluding WSS. In the supplementary material to this article, we have explained why WSS is insufficient to justify the response of ECs to flow directionality and local structures in transitional and turbulent flows.

Due to the aforementioned shortcomings of WSS, there has been a recently growing trend to link IA growth and rupture events with other flow variables such as vorticity, coherent structures and turbulence identifying parameters. Valencia et al.229 investigated the vortex ring structures and recirculation zones in IA models by inspecting the three-dimensional instantaneous velocity vector fields. They identified regimes of flow stability in the IA as function of the aneurysm tilt angle and showed the stabilizing effect of non-Newtonian blood viscosity. The local structures and energy cascade phenomena in IA were also investigated by means of DNS in several studies.173,191,230 These efforts are promising to link the biology and mechanotransducive responses of ECs to aneurysm pathology. In a pioneering attempt to probe such complex interaction, Varble et al.231 investigated the vortex structure in 204 patient-specific IAs using high resolution DNS and patient-specific boundary condition waveforms. They evidently shown that IA rupture is significantly correlated with the near-wall vortex structures as expressed in terms of the surface vortex fraction. The outcome of their study highlights a new correlation between aneurysm rupture and higher levels of rotationality and vorticity in the IA flow. This finding is evidently supported by ECs mechanotransduction, where flow disturbance initiates pro-inflammatory EC responses,66,232 degenerative progress and EC misalignment.118

Conclusion: towards next generation IA CFD models

The main challenges facing IA CFD currently have been summerized in the questions proposed in the aim and motivation section. Through the review and meta-analysis, it is evident that tackling such questions is impossible with the present IA CFD models which incorporates inappropriate simplifications, reliance on physically meaningless parameters, and loose computational representation of physiologic blood flow. Next generation IA CFD models must strive towards achiving the following objectives:

Capture more physics underlying IA hemodynamics

Provide meaningful parameters to distinguish the pathobiology-hemodynamics interaction in IA genesis, growth and rupture

Guide EC mechanotransduction studies by providing detailed quantitative and qualitative flow descriptions that can be used to trace biological factors influencing IA

In order to achieve such objectives, next generation IA CFD models must at least incorporate all of the following elements:

Patient-specific viscosity and blood flow waveforms

Direct numerical simulation or robust large eddy simulation scheme

Investigate the flow via one or more of the vector fields (such as vorticity) instead of scalar-tensor field (WSS or OSI)

In the end, modeling a complex biological system as IAs, which involves countless factors from the molecular and cellular levels to the complexities of the interacting blood flow, is never going to be a simple task. Indeed, in such a case some degree of simplification is always warranted, and of course justified. However, over-simplification in the modeling would eventually hinder us from capturing phenomena that could correlate the physics with the biology and ultimately enhace our understanding of the pathology of IAs.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for What does computational fluid dynamics tell us about intracranial aneurysms? A meta-analysis and critical review by Khalid M Saqr, Sherif Rashad, Simon Tupin, Kuniyasu Niizuma, Tamer Hassan, Teiji Tominaga and Makoto Ohta in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the support through the Collaborative Research Grant from the Institute of Fluid Science, Tohoku University.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a grant-in-aid for Young Scientists (A) (#17H04745, to KN) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions

KMS conceived and designed the study, contributed data, developed the mathematical models and wrote the paper. SR contributed data and wrote the paper. ST was responsible for the Software, statistics and visualization. KN, TH and TT critically revised the manuscript. MO was involved in funding acquisition, project management, and critical review of the paper. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplemental material

Supplemental material for this paper can be found at the journal website: http://journals.sagepub.com/home/jcb

References

- 1.Amenta PS, Yadla S, Campbell PG, et al. Analysis of nonmodifiable risk factors for intracranial aneurysm rupture in a large, retrospective cohort. Neurosurgery 2012; 70: 693–699. discussion 699–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rashad S, Hassan T, Aziz W, et al. Carotid artery occlusion for the treatment of symptomatic giant carotid aneurysms: a proposal of classification and surgical protocol. Neurosurg Review 2014; 37: 501–511. discussion 511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Algra AM, Lindgren A, Vergouwen MDI, et al. Procedural clinical complications, case-fatality risks, and risk factors in endovascular and neurosurgical treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurology 2019; 76(3): 282–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brisman JL, Song JK, Newell DW. Cerebral aneurysms. New Engl J Med 2006; 355: 928–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiebers DO, Whisnant JP, Huston J, 3rd, et al. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: natural history, clinical outcome, and risks of surgical and endovascular treatment. Lancet (London, England) 2003; 362: 103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cornelissen BM, Schneiders JJ, Potters WV, et al. Hemodynamic differences in intracranial aneurysms before and after rupture. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2015; 36: 1927–1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chien A, Sayre J. Morphologic and hemodynamic risk factors in ruptured aneurysms imaged before and after rupture. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35: 2130–2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugiyama SI, Endo H, Omodaka S, et al. Daughter sac formation related to blood inflow jet in an intracranial aneurysm. World Neurosurg 2016; 96: 396–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vlak MH, Algra A, Brandenburg R, et al. Prevalence of unruptured intracranial aneurysms, with emphasis on sex, age, comorbidity, country, and time period: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2011; 10: 626–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rashad S, Sugiyama SI, Niizuma K, et al. Impact of bifurcation angle and inflow coefficient on the rupture risk of bifurcation type basilar artery tip aneurysms. J Neurosurg 2018; 128: 723–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sugiyama S, Niizuma K, Sato K, et al. Blood flow into basilar tip aneurysms: a predictor for recanalization after coil embolization. Stroke 2016; 47: 2541–2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiebers DO, Torner JC, Meissner I. Impact of unruptured intracranial aneurysms on public health in the United States. Stroke 1992; 23: 1416–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baratchi S, Khoshmanesh K, Woodman OL, et al. Molecular sensors of blood flow in endothelial cells. Trends Mol Med 2017; 23(9): 850–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tarbell JM, Simon SI, Curry FR. Mechanosensing at the vascular interface. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 2014; 16: 505–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiu J-J, Chien S. Effects of disturbed flow on vascular endothelium: pathophysiological basis and clinical perspectives. Physiol Rev 2011; 91: 327–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Q, Meng Z, Zhang Y, et al. Phantom-based experimental validation of fast virtual deployment of self-expandable stents for cerebral aneurysms. BioMed Eng Online 2016; 28; 15(Suppl 2): 125.DOI: 10.1186/s12938-016-0250-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hergenreider E, Heydt S, Treguer K, et al. Atheroprotective communication between endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells through miRNAs. Nature Cell Biol 2012; 14: 249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Humphrey JD. Vascular adaptation and mechanical homeostasis at tissue, cellular, and sub-cellular levels. Cell Biochem Biophys 2008; 50: 53–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dolan JM, Kolega J, Meng H. High wall shear stress and spatial gradients in vascular pathology: a review. Ann Biomed Eng 2013; 41: 1411–1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cebral J, Ollikainen E, Chung BJ, et al. Flow conditions in the intracranial aneurysm lumen are associated with inflammation and degenerative changes of the aneurysm wall. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2017; 38: 119–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies PF, Remuzzi A, Gordon EJ, et al. Turbulent fluid shear stress induces vascular endothelial cell turnover in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1986; 83: 2114–2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miao H, Hu YL, Shiu YT, et al. Effects of flow patterns on the localization and expression of VE-cadherin at vascular endothelial cell junctions: in vivo and in vitro investigations. J Vasc Res 2005; 42: 77–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hosaka K, Hoh BL. Inflammation and cerebral aneurysms. Translat Stroke Res 2014; 5: 190–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Korkmaz E, Kleinloog R, Verweij BH, et al. Comparative ultrastructural and stereological analyses of unruptured and ruptured saccular intracranial aneurysms. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2017; 76: 908–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robertson AM, Duan X, Aziz KM, et al. Diversity in the strength and structure of unruptured cerebral aneurysms. Ann Biomed Eng 2015; 43: 1502–1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roach MR, Scott S, Ferguson GG. The hemodynamic importance of the geometry of bifurcations in the circle of willis (Glass model studies). Stroke 1972; 3: 255–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferguson GG. Physical factors in the initiation, growth, and rupture of human intracranial saccular aneurysms. J Neurosurg 1972; 37: 666–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferguson GG. Turbulence in human intracranial saccular aneurysms. J Neurosurg 1970; 33: 485–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steiger HJ, Reulen HJ. Low frequency flow fluctuations in saccular aneurysms. Acta neurochirurgica 1986; 83: 131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liepsch DW, Steiger HJ, Poll A, et al. Hemodynamic stress in lateral saccular aneurysms. Biorheology 1987; 24: 689–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gonzalez CF, Cho YI, Ortega HV, et al. Intracranial aneurysms: flow analysis of their origin and progression. Am J Neuroradiol 1992; 13: 181–188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim C, Cervós-Navarro J, Pätzold C, et al. In vivo study of flow pattern at human carotid bifurcation with regard to aneurysm development. Acta Neurochirurgica 1992; 115: 112–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burleson AC, Turitto VT. Identification of quantifiable hemodynamic factors in the assessment of cerebral aneurysm behavior: on behalf of the subcommittee on biorheology of the scientific and standardization committee of the ISTH. Thrombosis Haemostasis 1996; 76: 118–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steiger HJ, Liepsch DW, Poll A, et al. Hemodynamic stress in terminal saccular aneurysms: a laser-Doppler study. Heart Vessels 1988; 4: 162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liepsch D, Poll A, Steiger HJ, et al. Laser-Doppler-velocity-measurements in lateral aneurysms. In: In 1987 Biomechanics Symposium: presented at the 1987 ASME Applied Mechanics, Bioengineering, and Fluids Engineering Conference, Cincinnati, Ohio, June 14–17, 1987, Vol. 84, p.33. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 1987.

- 36.Tognetti F, Limoni P, Testa C. Aneurysm growth and hemodynamic stress. Surg Neurol 1983; 20: 74–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tognetti F, Andreoli A, Testa C. Hemodynamic mechanism in the angiographic disappearance of ruptured cerebral aneurysm. Surg Neurol 1984; 22: 412–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steiger HJ, Poll A, Liepsch D, et al. Haemodynamic stress in lateral saccular aneurysms – an experimental study. Acta Neurochirurgica 1987; 86: 98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steiger HJ, Poll A, Liepsch DW, et al. Haemodynamic stress in terminal aneurysms. Acta Neurochirurgica 1988; 93: 18–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steiger HJ, Aaslid R, Keller S, et al. Growth of aneurysms can be understood as passive yield to blood pressure – an experimental study. Acta Neurochirurgica 1989; 100: 74–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hassan T, Timofeev EV, Saito T, et al. Computational replicas: anatomic reconstructions of cerebral vessels as volume numerical grids at three-dimensional angiography. Am J Neuroradiol 2004; 25: 1356–1365. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sugiyama SI, Endo H, Omodaka S, et al. Daughter sac formation related to blood inflow jet in an intracranial aneurysm. World Neurosurg 2016; 96: 396–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sugiyama SI, Niizuma K, Nakayama T, et al. Relative residence time prolongation in intracranial aneurysms: a possible association with atherosclerosis. Neurosurgery 2013; 73: 767–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lasheras JC. The biomechanics of arterial aneurysms. Annual Rev Fluid Mech 2007; 39: 293–319. . [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sforza DM, Putman CM, Cebral JR. Hemodynamics of cerebral aneurysms. Ann Rev Fluid Mech 2009; 41: 91–107. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hassan T, Timofeev EV, Ezura M, et al. Hemodynamic analysis of an adult vein of Galen aneurysm malformation by use of 3D image-based computational fluid dynamics. Am J Neuroradiol 2003; 24: 1075–1082. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hassan T, Timofeev EV, Saito T, et al A proposed parent vessel geometry—based categorization of saccular intracranial aneurysms: computational flow dynamics analysis of the risk factors for lesion rupture. J Neurosurg 2005; 103: 662. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Chatziprodromou I, Tricoli A, Poulikakos D, et al. Haemodynamics and wall remodelling of a growing cerebral aneurysm: a computational model. J Biomech 2007; 40: 412–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cardamone L, Humphrey JD. Arterial growth and remodelling is driven by hemodynamics. Model Simulat Appl 2012; 5: 187–203. . [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meng H, Feng Y, Woodward SH, et al. Mathematical model of the rupture mechanism of intracranial saccular aneurysms through daughter aneurysm formation and growth. Neurol Res 2005; 27: 459–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hassan T, Ezura M, Timofeev EV, et al. Computational simulation of therapeutic parent artery occlusion to treat giant vertebrobasilar aneurysm. Am J Neuroradiol 2004; 25: 63–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Donaldson CJ, Lao KH, Zeng L. The salient role of microRNAs in atherogenesis. J Mol Cellular Cardiol 2018; 122: 98–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meng H, Tutino VM, Xiang J, et al. High WSS or low WSS? Complex interactions of hemodynamics with intracranial aneurysm initiation, growth, and rupture: toward a unifying hypothesis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35: 1254–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou G, Zhu Y, Yin Y, et al. Association of wall shear stress with intracranial aneurysm rupture: systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Rep 2017; 7: 5331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saqr KM, Mansour O, Tupin S, et al. Evidence for non-Newtonian behavior of intracranial blood flow from Doppler ultrasonography measurements. Med Biol Eng Comput 2018; 57(5): 1029–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saqr KM. Wall shear stress in the Navier-Stokes equation: a commentary. Comput Biol Med 2019; 106: 82–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Murray CD. The physiological principle of minimum work applied to the angle of branching of arteries. J General Physiol 1926; 9: 835–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ingebrigtsen T, Morgan MK, Faulder K, et al. Bifurcation geometry and the presence of cerebral artery aneurysms. J Neurosurg 2004; 101: 108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reneman RS, Hoeks APG. Wall shear stress as measured in vivo: consequences for the design of the arterial system. Med Biol Eng Comput 2008; 46: 499–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Beare RJ, Das G, Ren M, et al. Does the principle of minimum work apply at the carotid bifurcation: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Medical Imaging 2011; 11: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chnafa C, Bouillot P, Brina O, et al. Errors in power-law estimations of inflow rates for intracranial aneurysm CFD. J Biomech 2018; 80: 159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nixon AM, Gunel M, Sumpio BE. The critical role of hemodynamics in the development of cerebral vascular disease: a review. J Neurosurg 2010; 112: 1240–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Diehl RR, Linden D, Lücke D, et al. Phase relationship between cerebral blood flow velocity and blood pressure a clinical test of autoregulation. Stroke 1995; 26: 1801–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reinhard M, Wehrle-Wieland E, Grabiak D, et al. Oscillatory cerebral hemodynamics-the macro- vs. microvascular level. J Neurol Sci 2006; 250: 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Basarab MA, Basarab DA, Konnova NS, et al. Analysis of chaotic and noise processes in a fluctuating blood flow using the Allan variance technique. Clin Hemorheology Microcirculat 2016; 64: 921–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li YSJ, Haga JH, Chien S. Molecular basis of the effects of shear stress on vascular endothelial cells. J Biomech 2005; 38: 1949–1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Rev 2015; 4: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Westerhof N, Stergiopulos N and Noble MI. Snapshots of hemodynamics: an aid for clinical research and graduate education. New York, NY: Springer Science & Business Media, 2010.

- 69.Hoskins PR, Lawford PV and Doyle BJ. Cardiovascular biomechanics. New York, NY: Springer International Publishing, 2017.

- 70.Drazin PG, Riley N, Society LM, et al. The Navier-Stokes equations: a classification of flows and exact solutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- 71.Macosko CW. Rheology: principles, measurements, and applications. VCH, 1994.

- 72.Galdi GP, Rannacher R, Robertson AM, et al. Hemodynamical flows: modeling, analysis and simulation. Basel: Birkhäuser, 2008.

- 73.Shibeshi SS, Collins WE. The rheology of blood flow in a branched arterial system. Appl Rheology (Lappersdorf, Germany: Online) 2005; 15: 398–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Carreau PJ. Rheological equations from molecular network theories. Transact Soc Rheol 1972; 16: 99–127. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Campo-Deano L, Oliveira MSN, Pinho FT. A review of computational hemodynamics in middle cerebral aneurysms and rheological models for blood flow. Appl Mech Rev 2015, pp. 67. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Schirmer CM, Malek AM. Critical influence of framing coil orientation on intra-aneurysmal and neck region hemodynamics in a sidewall aneurysm model. Neurosurgery 2010; 67: 1692–1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gijsen FJH, van de Vosse FN, Janssen JD. The influence of the non-Newtonian properties of blood on the flow in large arteries: steady flow in a carotid bifurcation model. J Biomech 1999; 32: 601–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bernabeu MO, Nash RW, Groen D, et al. Impact of blood rheology on wall shear stress in a model of the middle cerebral artery. Interface focus 2013; 3: 20120094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Boyd J, Buick JM, Green S. Analysis of the Casson and Carreau-Yasuda non-Newtonian blood models in steady and oscillatory flows using the lattice Boltzmann method. Phys Fluids 2007; 19: 093103. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim S, Namgung B, Ong PK, et al. Determination of rheological properties of whole blood with a scanning capillary-tube rheometer using constitutive models. J Mech Sci Technol 2009; 23: 1718–1726. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bodnár T, Sequeira A, Pirkl L. Numerical simulations of blood flow in a stenosed vessel under different flow rates using a generalized Oldroyd-B model. AIP Conference Proc 2009; 1168: 645–648. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Burleson AC, Strother CM, Turitto VT. Computer modeling of intracranial saccular and lateral aneurysms for the study of their hemodynamics. Neurosurgery 1995; 37: 774–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ortega HV. Predicting cerebral aneurysms with CFD. Mech Eng 1997; 119: 76–77. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cebral JR, Castro MA, Burgess JE, et al. Characterization of cerebral aneurysms for assessing risk of rupture by using patient-specific computational hemodynamics models. Am J Neuroradiol 2005; 26: 2550–2559. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shojima M, Oshima M, Takagi K, et al. Magnitude and role of wall shear stress on cerebral aneurysm: computational fluid dynamic study of 20 middle cerebral artery aneurysms. Stroke 2004; 35: 2500–2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cebral JR, Castro MA and Putman CM. A study of the hemodynamics of anterior communicating artery aneurysms. In: Progress in biomedical optics and imaging – proceedings of SPIE, 11–16 February 2006, San Diego, California, United States.

- 87.Cebral JR, Mut F, Weir J, et al. Quantitative characterization of the hemodynamic environment in ruptured and unruptured brain aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011; 32: 145–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Castro MA, Putman CM, Cebral JR. Computational fluid dynamics modeling of intracranial aneurysms: effects of parent artery segmentation on intra-aneurysmal hemodynamics. Am J Neuroradiol 2006; 27: 1703–1709. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cebral JR, Castro MA, Millan D, et al. Pilot clinical study of aneurysm rupture using image-based computational fluid dynamics models. In: Progress in biomedical optics and imaging – proceedings of SPIE, 12–17 February 2005, San Diego, California, United States, pp.245–256.

- 90.Goubergrits L, Schaller J, Kertzscher U, et al. Statistical wall shear stress maps of ruptured and unruptured middle cerebral artery aneurysms. J Royal Society Interface 2012; 9: 677–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Omodaka S, Sugiyama SI, Inoue T, et al. Local hemodynamics at the rupture point of cerebral aneurysms determined by computational fluid dynamics analysis. Cerebrovasc Dis 2012; 34: 121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rashad S, Sugiyama SI, Niizuma K, et al. Impact of bifurcation angle and inflow coefficient on the rupture risk of bifurcation type basilar artery tip aneurysms. J Neurosurg 2018; 128: 723–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Boussel L, Rayz V, McCulloch C, et al. Aneurysm growth occurs at region of low wall shear stress: Patient-specific correlation of hemodynamics and growth in a longitudinal study. Stroke 2008; 39: 2997–3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sugiyama SI, Meng H, Funamoto K, et al. Hemodynamic analysis of growing intracranial aneurysms arising from a posterior inferior cerebellar artery. World Neurosurg 2012; 78: 462–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Xiang J, Tutino VM, Snyder KV, et al. CFD: Computational fluid dynamics or confounding factor dissemination? the role of hemodynamics in intracranial aneurysm rupture risk assessment. Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35: 1849–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fiorella D, Sadasivan C, Woo HH, et al. Regarding “aneurysm rupture following treatment with flow-diverting stents: Computational hemodynamics analysis of treatment”. Am J Neuroradiol 2011; 32: E95–E97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Robertson AM, Watton PN. Computational fluid dynamics in aneurysm research: critical. Am J Neuroradiol 2012; 33: 992–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Taylor CA, Humphrey JD. Open problems in computational vascular biomechanics: hemodynamics and arterial wall mechanics. Comput Meth Appl Mech Eng 2009; 198: 3514–3523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Humphrey JD, Taylor CA. Intracranial and abdominal aortic aneurysms: similarities, differences, and need for a new class of computational models. Ann Rev Biomed Eng 2008; 10: 221–246. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Can A, Du R. Association of hemodynamic factors with intracranial aneurysm formation and rupture: systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosurgery 2016; 78: 510–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhou G, Zhu Y, Yin Y, et al. Association of wall shear stress with intracranial aneurysm rupture: systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports 2017; 7: 5331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Meng H, Tutino VM, Xiang J, et al. High WSS or Low WSS? Complex interactions of hemodynamics with intracranial aneurysm initiation, growth, and rupture: toward a unifying hypothesis. Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35: 1254–1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Janiga G, Daróczy L, Berg P, et al. An automatic CFD-based flow diverter optimization principle for patient-specific intracranial aneurysms. J Biomech 2015; 48: 3846–3852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ma D, Dumont TM, Kosukegawa H, et al. High fidelity virtual stenting (HiFiVS) for intracranial aneurysm flow diversion: In vitro and in silico. Ann Biomed Eng 2013; 41: 2143–2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Paliwal N, Yu H, Xu J, et al. Virtual stenting workflow with vessel-specific initialization and adaptive expansion for neurovascular stents and flow diverters. Comput Meth Biomech Biomed Eng 2016; 19: 1423–1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Song Y, Choe J, Liu H, et al. Virtual stenting of intracranial aneurysms: application of hemodynamic modification analysis. Acta Radiologica 2016; 57: 992–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Shobayashi Y, Tateshima S, Kakizaki R, et al. Intra-aneurysmal hemodynamic alterations by a self-expandable intracranial stent and flow diversion stent: high intra-aneurysmal pressure remains regardless of flow velocity reduction. J Neurointerventional Surg 2013; 5: iii38–iii42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zhang Y, Chong W, Qian Y. Investigation of intracranial aneurysm hemodynamics following flow diverter stent treatment. Med Eng Phys 2013; 35: 608–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Dholakia R, Sadasivan C, Fiorella DJ, et al. Hemodynamics of flow diverters. J Biomech Eng 2017; 139: 139–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Alderazi YJ, Shastri D, Kass-Hout T, et al. Flow diverters for intracranial aneurysms. Stroke Res Treat 2014, pp. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tse MMY, Yan B, Dowling RJ, et al. Current status of pipeline embolization device in the treatment of intracranial aneurysms: a review. World Neurosurg 2013; 80: 829–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Dorn F, Niedermeyer F, Balasso A, et al. The effect of stents on intra-aneurysmal hemodynamics: in vitro evaluation of a pulsatile sidewall aneurysm using laser Doppler anemometry. Neuroradiology 2011; 53: 267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Jeong W, Han MH, Rhee K. Effects of framing coil shape, orientation, and thickness on intra-aneurysmal flow. Med Biol Eng Comput 2013; 51: 981–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Baráth K, Cassot F, Fasel JHD, et al. Influence of stent properties on the alteration of cerebral intra-aneurysmal haemodynamics: flow quantification in elastic sidewall aneurysm models. Neurol Res 2005; 27: S120–S128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wu YF, Yang PF, Shen J, et al. A comparison of the hemodynamic effects of flow diverters on wide-necked and narrow-necked cerebral aneurysms. J Clin Neurosci 2012; 19: 1520–1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Mut F, Ruijters D, Babic D, et al. Effects of changing physiologic conditions on the in vivo quantification of hemodynamic variables in cerebral aneurysms treated with flow diverting devices. Int J Num Meth Biomed Eng 2014; 30: 135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Dolan JM, Meng H, Sim FJ, et al. Differential gene expression by endothelial cells under positive and negative streamwise gradients of high wall shear stress. Am J Physiol – Cell Physiol 2013; 305: C854–C866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chiu JJ, Chien S. Effects of disturbed flow on vascular endothelium: pathophysiological basis and clinical perspectives. Physiol Rev 2011; 91: 327–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Avari H, Savory E, Rogers KA. An in vitro hemodynamic flow system to study the effects of quantified shear stresses on endothelial cells. Cardiovasc Eng Technol 2016; 7: 44–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Dolan JM, Sim FJ, Meng H, et al. Endothelial cells express a unique transcriptional profile under very high wall shear stress known to induce expansive arterial remodeling. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2012; 302: C1109–C1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Taba Y, Sasaguri T, Miyagi M, et al. Fluid shear stress induces lipocalin-type prostaglandin D2 synthase expression in vascular endothelial cells. Circulat Res 2000; 86: 967–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Partridge J, Carlsen H, Enesa K, et al. Laminar shear stress acts as a switch to regulate divergent functions of NF-κB in endothelial cells. Faseb J 2007; 21: 3553–3561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Dolan JM, Meng H, Singh S, et al. High fluid shear stress and spatial shear stress gradients affect endothelial proliferation, survival, and alignment. Ann Biomed Eng 2011; 39: 1620–1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Chalouhi N, Hoh BL, Hasan D. Review of cerebral aneurysm formation, growth, and rupture. Stroke 2013; 44: 3613–3622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Fukuda S, Shimogonya Y. The role of hemodynamic factors on the development, enlargement, and rupture of cerebral aneurysms: a combination of computational fluid dynamics analysis and an animal model study. Japanese J Neurosurg 2014; 23: 661–666. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Turjman AS, Turjman F, Edelman ER. Role of fluid dynamics and inflammation in intracranial aneurysm formation. Circulation 2014; 129: 373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zhou G, Zhu Y, Yin Y, et al. Association of wall shear stress with intracranial aneurysm rupture: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 5331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Hudson JS, Hoyne DS, Hasan DM. Inflammation and human cerebral aneurysms: current and future treatment prospects. Future Neurol 2013; 8: 663–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Bouillot P, Brina O, Ouared R, et al. Multi-time-lag PIV analysis of steady and pulsatile flows in a sidewall aneurysm. Experiment Fluids 2014; 55: 1746–1757. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Farnoush A, Avolio A, Qian Y. Effect of bifurcation angle configuration and ratio of daughter diameters on hemodynamics of bifurcation aneurysms. Am J Neuroradiol 2013; 34: 391–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Rafat M, Stone HA, Auguste DT, et al. Impact of diversity of morphological characteristics and Reynolds number on local hemodynamics in basilar aneurysms. AIChE J 2018; 64: 2792–2802. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Baharoglu MI, Schirmer CM, Hoit DA, et al. Aneurysm inflow-angle as a discriminant for rupture in sidewall cerebral aneurysms: morphometric and computational fluid dynamic analysis. Stroke 2010; 41: 1423–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ford MD, Lee SW, Lownie SP, et al. On the effect of parent-aneurysm angle on flow patterns in basilar tip aneurysms: towards a surrogate geometric marker of intra-aneurismal hemodynamics. J Biomech 2008; 41: 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Wang C, Tian Z, Liu J, et al. Hemodynamic alterations for various stent configurations in idealized wide-neck basilar tip aneurysm. J Med Biol Eng 2016; 36: 379–385. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Otani T, Nakamura M, Fujinaka T, et al. Computational fluid dynamics of blood flow in coil-embolized aneurysms: effect of packing density on flow stagnation in an idealized geometry. Med Biol Eng Comput 2013; 51: 901–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Lindekleiv HM, Valen-Sendstad K, Morgan MK, et al. Sex differences in intracranial arterial bifurcations. Gender Med 2010; 7: 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Retarekar R, Ramachandran M, Berkowitz B, et al. Stratification of a population of intracranial aneurysms using blood flow metrics. Comput Meth Biomech Biomed Eng 2015; 18: 1072–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Castro MA, Peloc NL, Putman CM, et al. Computational hemodynamic study of intracranial aneurysms coexistent with proximal artery stenosis. In: Progress in biomedical optics and imaging – Proceedings of SPIE, 4–9 February 2012, San Diego, California, United States.

- 139.Berg P, Saalfeld S, Voß S, et al. Does the DSA reconstruction kernel affect hemodynamic predictions in intracranial aneurysms? An analysis of geometry and blood flow variations. J Neurointerventional Surg 2018; 10: 290–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Jain K, Roller S, Mardal KA. Transitional flow in intracranial aneurysms – a space and time refinement study below the Kolmogorov scales using Lattice Boltzmann Method. Comput Fluids 2016; 127: 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Xu L, Liang F, Gu L, et al. Flow instability detected in ruptured versus unruptured cerebral aneurysms at the internal carotid artery. J Biomech 2018; 72: 187–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Varble N, Xiang J, Lin N, et al. Flow instability detected by high-resolution computational fluid dynamics in fifty-six middle cerebral artery aneurysms. J Biomech Eng 2016; 138(6): 061009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Poelma C, Watton PN, Ventikos Y. Transitional flow in aneurysms and the computation of haemodynamic parameters. J Royal Society Interface 2015; 12(105): 20141394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Yagi T, Sato A, Shinke M, et al. Experimental insights into flow impingement in cerebral aneurysm by stereoscopic particle image velocimetry: transition from a laminar regime. J Royal Soc Interface 2013; 10(82): 20121031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Otani T, Ii S, Fujinaka T, et al. Blood flow analysis in patient-specific cerebral aneurysm models with realistic configuration of embolized coils. In: IFMBE Proceedings 2014 4th–7th December 2013, Singapore, pp.343-346.

- 146.Babiker MH, Chong B, Gonzalez LF, et al. Finite element modeling of embolic coil deployment: Multifactor characterization of treatment effects on cerebral aneurysm hemodynamics. J Biomech 2013; 46: 2809–2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Oshima M, Torii R, Kobayashi T, et al. Finite element simulation of blood flow in the cerebral artery. Comput Meth Appl Mech Eng 2001; 191: 661–671. [Google Scholar]

- 148.Foutrakis GN, Yonas H, Sclabassi RJ. Finite element methods in the simulation and analysis of intracranial blood flow. Neurol Res 1997; 19: 174–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Sun SR, Huang CS, Wang L, et al. Stent effects on hemodynamics of cerebral aneurysm by non-uniform lattice Boltzmann method. Yiyong Shengwu Lixue/J Med Biomech 2015; 30: 104–110. [Google Scholar]

- 150.Huang C, Shi B, Guo Z, et al. Multi-GPU based lattice boltzmann method for hemodynamic simulation in patient-specific cerebral aneurysm. Commun Computat Phys 2015; 17: 960–974. [Google Scholar]

- 151.Shi Y, Tang GH, Tao WQ. Lattice Boltzmann study ofnon-newtonian blood flow in mother and daughter aneurysm and a novel stent treatment. Adv Appl Math Mech 2014; 6: 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- 152.Geers AJ, Larrabide I, Morales HG, et al. Approximating hemodynamics of cerebral aneurysms with steady flow simulations. J Biomech 2014; 47: 178–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Le TB, Troolin DR, Amatya D, et al. Vortex phenomena in sidewall aneurysm hemodynamics: experiment and numerical simulation. Ann Biomed Eng 2013; 41: 2157–2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Venugopal P, Valentino D, Schmitt H, et al. Sensitivity of patient-specific numerical simulation of cerebal aneurysm hemodynamics to inflow boundary conditions. J Neurosurg 2007; 106: 1051–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Pereira VM, Brina O, Marcos Gonzales A, et al. Evaluation of the influence of inlet boundary conditions on computational fluid dynamics for intracranial aneurysms: a virtual experiment. J Biomech 2013; 46: 1531–1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]