Abstract

Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging of the translocator protein (TSPO) is widely used as a biomarker of microglial activation. However, TSPO protein concentration in human brain has not been optimally quantified nor has its regional distribution been compared to TSPO binding. We determined TSPO protein concentration, change with age, and regional distribution by quantitative immunoblotting in autopsied human brain. Brain TSPO protein concentration (>0.1 ng/µg protein) was higher than those reported by in vitro binding assays by at least 2 to 70 fold. TSPO protein distributed widely in both gray and white matter regions, with distribution in major gray matter areas ranked generally similar to that of PET binding in second-generation radiotracer studies. TSPO protein concentration in frontal cortex was high at birth, declined precipitously during the first three months, and increased modestly during adulthood/senescence (10%/decade; vs. 30% for comparison astrocytic marker GFAP). As expected, TSPO protein levels were significantly increased (+114%) in degenerating putamen in multiple system atrophy, providing further circumstantial support for TSPO as a gliosis marker. Overall, findings show some similarities between TSPO protein and PET binding characteristics in the human brain but also suggest that part of the TSPO protein pool might be less available for radioligand binding.

Keywords: Translocator protein TSPO, postmortem human brain, aging, multiple system atrophy, positron emission tomography

The 18-kDa translocator protein (TSPO), previously known as peripheral benzodiazepine receptor,1 was initially described as the high affinity binding site in peripheral tissues, e.g. kidney for the atypical benzodiazepine Ro5-4864.2 This binding site was also found in healthy brain of animals (e.g. rats) though of a much lower concentration than that in peripheral organs.3,4 A variety of animal models of brain injury was found to have a marked increase in levels of the binding site in the damaged brain, assessed with tritium-labelled Ro5-4864 and/or the prototypical TSPO ligand PK11195,5–11 which was associated with activated glial cells, in particular, microglia.5,10–12 Although TSPO function is not understood and continues to be debated,13–19 over the past 30 years, brain imaging with positron-labelled radioligands binding to TSPO by positron emission tomography (PET) has been extensively employed as a biomarker of microglial activation or more generally, often ill-defined “neuroinflammation”. A number of PET radiotracers for TSPO have been developed and employed in clinical research of different neuropsychiatric conditions. Examples include [11C](R)-PK11195, the first generation TSPO ligand,20,21 but limitations of its lower sensitivity and higher non-specific binding in vivo led to development of many second generation ligands with improved affinity and specificity, e.g. [11C]PBR28,22,23 [18F]-FEPPA,24–28 [18F]DPA-714,29,30 [18F]-PBR111,31,32 and [18F]GE-18033,34 (see literature35,36 for reviews).

Despite TSPO’s wide use as a PET microglial imaging target, some basic questions remain: thus, it is surprising that actual levels of TSPO protein in healthy human brain are still uncertain. In this regard, our knowledge on TSPO abundance in human brain has been largely derived from radioligand binding assay and autoradiography using [3H]Ro5-4864,37 [3H]PK1119537–46 or the stereo-specific [3H](R)-PK1119547–50 and more recently also the second generation ligands [3H]DAA110648,49 and [3H]PBR28.46 However, these assays have produced inconsistent results on estimates of concentrations of the TSPO binding site in postmortem human brain (see Supplementary Table 1 for a review and the Discussion37–50; see also Cumming et al.35 for a general discussion on the discrepancy between in vitro and in vivo TSPO binding measures). There has also been no systematic examination of the extent of correlation between regional brain TSPO levels and in vivo PET outcome measures of TSPO binding. Therefore, it is unknown whether the outcome measures of PET TSPO binding obtained at tracer dose of a radioligand by kinetic modeling are quantitatively related to actual levels of its target protein in brain. It is also uncertain whether human aging is associated with increased levels of the biomarker of microglial activation, with inconsistent findings in the PET literature.32,51–56 Finally, in comparison to the extensive literature on PET TSPO binding in human brain disorders, there is still only limited information on the behavior of brain TSPO protein assessed quantitatively in degenerative conditions in which gliosis is known to be present.5,9,20,41,44,49,50,57–60 The present study was designed to address the above literature deficiencies by employing quantitative immunoblotting and recombinant TSPO to measure TSPO protein in normal (including regional distribution) and developing/aging human brain and in degenerating brain of persons with multiple system atrophy (MSA), a movement disorder associated with brain gliosis.61–64 For the regional and aging studies, we also employed glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP), a widely used, arguably the most specific, astroglial marker for comparison with TSPO, a putative microglial marker that was shown to be also expressed in astrocytes, perhaps to a minor extent, in normal human brain65 (see also Guilarte66). GFAP also served as a control protein, with its levels calibrated in postmortem human brain by a sandwiched ELISA assay.67

Materials and methods

Subjects

All procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Board of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (Toronto, Canada) and performed in accordance with the TriCouncil Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS 2) and Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA 2004). Informed consent was obtained from all donors or their next of kin. A total of six (4M/2F) autopsied brains from neurologically normal subjects [age: 48 [0.8] (47–49) years; postmortem interval (PMI): 16 [7] (5.25-23) hours; mean [SD] (range)] were used in the TSPO regional distribution study (see Table 2 for a full list of the cortical and subcortical regions sampled). To evaluate age and development related changes of TSPO and GFAP, frontal cortex (Brodmann area 10) from a total of 69 subjects (42M/27F) was used, with age ranging from 21 hours to 99 years old and a mean PMI of 13 [6] (3–27) hours (see Tong et al.68 for details including causes of death. Neuropathological examination of the fixed half brain did not disclose any obvious pathological changes in these subjects). For evaluation of TSPO as a marker of microgliosis, autopsied brains (putamen) were obtained from patients with multiple system atrophy (MSA, n = 9) and matched controls (n = 16). No significant difference was found in postmortem interval (hours) (control: 12 [5]; MSA: 14 [6]; mean [SD]) or age (years) (control: 71 [8]; MSA: 65 [10]) among the two groups. The causes of death for the aged controls were cardiovascular illnesses (10), bronchopneumonia (2), pulmonary edema (2), breast cancer (1), and natural death (1). One half-brain was used for neuropathological examination, whereas the other half was frozen for neurochemical analyses. Neuropathological findings of neuronal loss by routine haematoxylin-eosin stain and assessments of the pathological hallmarks including Lewy bodies, glial cytoplasmic inclusions and neurofibrillary tangles in brains of patients with MSA were previously reported.62,69,70

Table 2.

Regional distribution of TSPO, as compared to GFAP, in autopsied human brain.

| Brain regions | TSPO | GFAP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basal brain areas | Hypothalamus | 0.44 (0.15) | 5.69 (1.92) |

| Nucleus basalis | 0.31 (0.10) | 4.67 (2.12) | |

| Substantia innominata | 0.23 (0.06) | 5.13 (2.55) | |

| Thalamus | Lateroventral nucleus | 0.27 (0.09) | 2.96 (3.26) |

| Anteroventral nucleus | 0.22 (0.05) | 3.79 (3.08) | |

| Medial pulvinar nucleus | 0.20 (0.07) | 3.84 (1.98) | |

| Mediodorsal nucleus | 0.19 (0.05) | 2.12 (2.63) | |

| Lateral nucleus | 0.17 (0.05) | 2.53 (2.58) | |

| Subthalamic nucleus | 0.31 (0.04) | 2.05 (1.83) | |

| Midbrain | Red nucleus | 0.27 (0.04) | 2.08 (1.79) |

| Substantia nigra pars compacta | 0.20 (0.09) | 3.51 (2.74) | |

| Pallidum | Globus pallidus, internal | 0.25 (0.12) | 2.74 (1.85) |

| Globus pallidus, external | 0.23 (0.10) | 2.61 (1.04) | |

| Striatum | Caudate nucleus | 0.16 (0.01) | 1.14 (1.51) |

| Putamen | 0.15 (0.03) | 0.91 (0.86) | |

| Hippocampus | Hippocampal uncus | 0.30 (0.10) | 5.62 (1.51) |

| Hippocampal gyrus | 0.20 (0.05) | 2.67 (1.17) | |

| Dentate gyrus | 0.19 (0.05) | 3.28 (1.41) | |

| Hippocampal Ammon’s horn | 0.18 (0.08) | 3.72 (2.08) | |

| Amygdala | Nucleus amygdaloid | 0.18 (0.04) | 1.99 (1.30) |

| Cingulate | Cingulate cortex, anterior, subgenual (A25) | 0.34 (0.18) | 5.87 (2.75) |

| Cingulate cortex, anterior (A24) | 0.22 (0.06) | 2.67 (0.79) | |

| Cingulate cortex, posterior (A23) | 0.19 (0.05) | 1.31 (1.15) | |

| Insula | Insular cortex | 0.17 (0.05) | 1.96 (1.23) |

| Frontal | Frontal lobe, medial prefrontal cortex (A10m) | 0.19 (0.04) | 1.68 (0.75) |

| Frontal pole (A10) | 0.18 (0.07) | 0.80 (0.56) | |

| Frontal lobe, supplementary motor cortex (A6) | 0.20 (0.07) | 1.72 (1.11) | |

| Frontal lobe, primary motor cortex (A4) | 0.19 (0.06) | 1.60 (0.72) | |

| Temporal | Temporal lobe, lateral temporal cortex (A21) | 0.14 (0.04) | 0.68 (0.77) |

| Parietal | Parietal lobe, superior parietal cortex (A7b) | 0.15 (0.05) | 1.35 (1.05) |

| Parietal lobe, inferior parietal cortex A39 | 0.21 (0.08) | 1.62 (0.71) | |

| Occipital | Occipital lobe, occipital cortex (A19) | 0.17 (0.05) | 1.61 (1.44) |

| Occipital lobe, occipital pole (A17) | 0.17 (0.06) | 2.01 (2.28) | |

| Cerebellum | Cerebellar cortex | 0.13 (0.04) | 0.89 (0.98) |

| White matter | Internal capsule | 0.14 (0.04) | 2.98 (1.22) |

| Corpus callosum, caudal | 0.20 (0.10) | 3.06 (1.26) | |

| Corpus callosum, rostral | 0.23 (0.05) | 2.75 (1.90) |

Note: Values in mean (SD) (n = 6) of levels of TSPO and GFAP (ng/µg tissue protein).

Tissue sample preparation, SDS-PAGE, and Western blotting

For all the postmortem frozen half brain materials obtained, cerebral cortical subdivisions were excised according to Brodmann classification. Dissection of the subcortical areas from ∼3 mm thick coronal sections followed published procedures.71 Brain tissue homogenates were used throughout this study. Sample preparation, SDS-PAGE, and Western blot followed published procedures.62,68 Protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard. Five concentrations of tissue standard (2.5–15 µg of protein), consisting of pooled human cerebral cortex samples, were run on each blot together with the samples (2.5–10 µg of protein, depending on regional levels of TSPO and GFAP). The antibodies used for quantitative determination of levels of TSPO and GFAP were a rabbit monoclonal antibody from Abcam (ab109497, clone EPR5384) and a mouse monoclonal antibody from Chemicon/Millipore (MAB360, IgG1 isotype, raised against purified GFAP from porcine spinal cord), respectively (see Table 1 for other TSPO antibodies tested and used for cross examination). For antibody characterization and quantitative measurement, recombinant TSPO proteins of human, mouse and rat origins were obtained from several sources (Table 1). Concentrations of the purified or partially purified recombinant TSPO proteins were calibrated by SDS-PAGE against a serial concentration of BSA (0.25-7.5 µg).68,72 Levels of GFAP in the tissue standard were calibrated using purified porcine GFAP by a sandwiched ELISA assay reported previously.67 To help in the characterization of TSPO, immunoblotting was also conducted in homogenates of adrenal gland obtained from three subjects (a 16-year-old male user of ecstasy [3,4-methyl-enedioxy-methamphetamine, MDMA], a 68-year-old female patient with dystonia, and a 90-year-old female subject who died from complications due to stroke). The coefficients of variation were <10% for all the proteins examined within and between blots. For simplicity only, “immunoreactivity” of the proteins examined will be referred to as “levels”. No significant correlation (Pearson) was observed between levels of either TSPO or GFAP protein and PMI of the subjects examined.

Table 1.

Antibody and recombinant protein sources and conditions used.

| Supplier | Cat# | Isotype | Epitope | Working dilution | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||||||

| TSPO1 (18 kDa, 169aa) | Abcam | ab109497 | rMonoAb (EPR5384) | aa150-169 | 1:100K | Good reactivity & selectivity for 18 kDa TSPO |

| ThermoFisher | MA5-24844 | rMonoAb (4H2) | C-terminal | 1:30K | Good reactivity & selectivity for 18 kDa TSPO | |

| ThermoFisher | PA5-75544 | rPolyAb | 124-169 | 1:10K | Some cross reactivity at higher MW | |

| Bio-Rad | VPA-00789 | rPolyAb | C-terminal | 1:2K | Low reactivity & selectivity for human brain TSPO | |

| Origene | TA303138 | gPolyAb | aa156-169 | NA | Major band at 35 kDa? | |

| Abnova | H00000706-M01 | Mouse IgG1k (3D8-B2) | Unknown | NA | No major band identified | |

| Santa Cruz Biotech | Sc-20120 | rPolyAb (FL-169) | Unknown | NA | No major band identified | |

| GFAP (50,48,45,and 43 kDa) | Chemicon/Millipore | MAB360 | Mouse IgG1 | Unknown | 1:100K | |

| Vimentin (57 kDa) | Santa Cruz Biotech | Sc-6260 | Mouse IgG1 | Unknown | 1:2K | |

| 2nd antibodies | ||||||

| Anti-rabbit IgG-HRP | Southern Biotech | 4050-05 | Goat IgG | 1:10-20K | ||

| Anti-mouse IgG1-HRP | Southern Biotech | 1070-05 | Goat IgG | 1:10K | ||

| Anti-goat IgG-HRP | Southern Biotech | 6160-05 | Rabbit IgG | 1:10K | ||

| Recombinant TSPO | ||||||

| Human TSPO, N-His | Creative BioMart | TSPO-3462H | / | / | 0.1 ng | 21 kDa |

| Human TSPO, N-His/GST | Creative BioMart | TSPO-1696H | / | / | <1 ng | 48.8 kDa (crude lysate) |

| Human TSPO, C-Myc/DDK | Origene | TP320107 | / | / | 40 ng | 23 kDa |

| Mouse TSPO, N-His | Jean J. Lacapere | Gift | / | / | 1 ng | 21 kDa |

| Mouse TSPO, C-Myc/DDK | Origene | TP605624 | / | / | NA | 23 kDa |

| Rat TSPO, C-Myc/DDK | Origene | TP605625 | / | / | NA | 23 kDa |

Data analyses

All quantitative immunoblotting data are expressed in ng/µg protein of tissue homogenates. On average, the white matter regions (corpus callosum and internal capsule) had a protein concentration per mg tissue weight 23% lower than the grey matter regions sampled including frontal cortex, hippocampus, and substantia nigra pars compacta; therefore, levels of protein of interest in the white matter regions as determined above were multiplied by 0.77 to correct for the difference in total protein concentration between white and grey matters. This correction was necessary for meaningful comparison of regional PET binding (per volume) with TSPO protein levels (per total protein). There was no significant difference in total protein levels (mg protein/mg wet tissue) among the cortical and subcortical grey matter regions sampled. Statistical analyses were performed by using StatSoft STATISTICA 7.1 (Tulsa, Oklahoma, USA). TSPO/GFAP regional distribution was examined by one-way ANOVA. The 37 brain regions examined were also grouped into 15 brain areas (see Table 2) and the mean values were also examined by one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc LSD (Least Significant Difference) tests. Possible correlations between TSPO and GFAP levels vs. age of the subjects and between regional protein levels vs. literature data of TSPO binding were examined by Pearson product-moment correlation. To assess correlations between TSPO protein vs. TSPO binding amongst the different brain grey matter areas, the following regions were employed, with subregional averages calculated if necessary: thalamus, midbrain, globus pallidus, hippocampus, amygdala, cerebral cortical areas (cingulate, insula, frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital cortices), cerebellar cortex, and striatum (caudate and putamen). The white matter was excluded from the correlation analysis because of its different kinetic characteristics, e.g. blood supply,73 from the grey matter in in vivo PET imaging. F-tests of the null-hypotheses, y-intercept = 0 or two slopes are equal for the linear correlations were performed by using GraphPad Prism 4.0.

Results

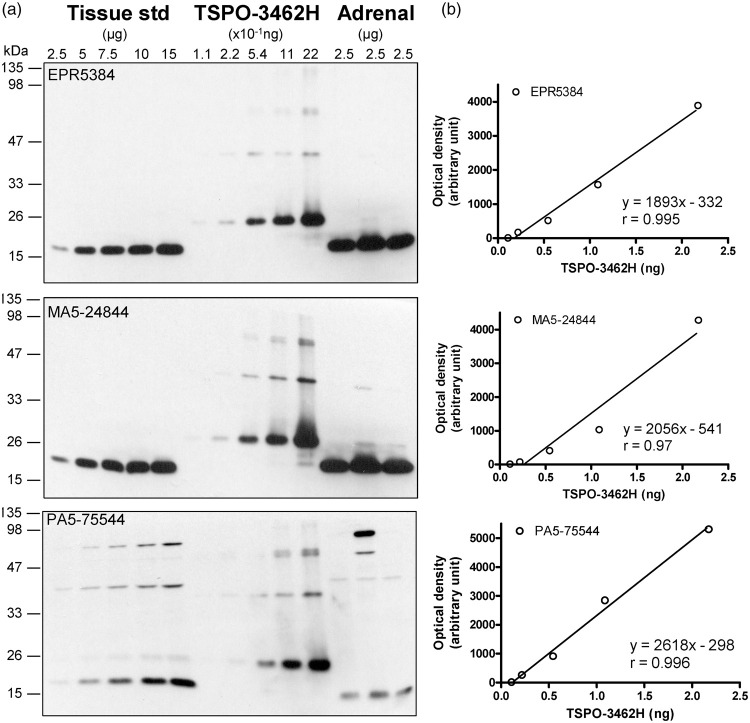

Characterization of TSPO antibodies for Western blotting in human brain

Several TSPO antibodies were tested in homogenates of autopsied human brain and adrenal samples together with recombinant TSPO proteins from different sources (Table 1; see Supplementary Results for more details). As shown in Figure 1(a), the rabbit monoclonal antibody EPR5384 was found to have the optimal specificity and sensitivity for Western blotting in human brain homogenates; the rabbit monoclonal (MA5-24844, 4H2) and polyclonal (PA5-75544) antibodies were also suitable for the brain but with lower sensitivity, with the latter having more non-specific reactivity and not suitable for the adrenal; several other antibodies were found not suitable for the brain mainly because of much non-specific reactivity (Supplement Figure 1B-D). The N-His tagged TSPO-3462H was found to be of sufficient purity for TSPO calibration whereas the N-His/GST tagged TSPO-1696H (crude extract) or the C-Myc/DDK tagged TSPO of human, rat and mouse origin (epitope interference) were not suitable. N-His tagged TSPO proteins, both TSPO-3462H and recombinant mouse TSPO (from Dr. J. J. Lacapere),74 had a small amount of aggregates, likely dimers, trimers and tetramers of TSPO,75 which was also detected by the antibodies (Figure 1(a) and Supplement Figure 1A). However, no TSPO polymer was detectable in the human brain SDS-PAGE sample preparation.

Figure 1.

Quantification of TSPO protein in autopsied human brain. (a) Immunoblots of TSPO in the pooled tissue standards, in the commercial N-His-tagged recombinant human TSPO-3462H and in human adrenal samples with monoclonal (EPR5384, 1:100K and MA5-24844, 1:30K dilution) and polyclonal (PA5-75544, 1:10K) antibodies. (b) Standard curves for the recombinant TSPO. Note more abundant TSPO in adrenal than in brain for both EPR5384 and MA5-24844, polymer protein bands of the recombinant TSPO, high molecular weight non-specific reactions for PA5-75544, and detection of a TSPO fragment but not 18 kDa TSPO by PA5-75544 in human adrenal samples.

TSPO levels in normal human brain

Given the high specificity and sensitivity of the rabbit monoclonal antibody EPR5384, it was selected for the following quantitative measurement in human brains. TSPO protein levels in the commercial partially purified recombinant TSPO-3462H were first calibrated with BSA standard and were determined to be 2.17 (0.31) µg/µg protein (eight determinations). Afterwards, TSPO-3462H was used to calibrate TSPO levels in the pooled tissue standard employed in quantitative Western blotting assays, which was determined to be 0.147 (0.012) ng/µg protein by EPR5384 (Figure 1(b)). Similar levels were also obtained with the rabbit monoclonal (4H2) antibody MA5-24844 (0.149 [0.019] ng/µg protein) although a lower level was obtained with the rabbit polyclonal antibody PA5-75544 (0.082 [0.012] ng/µg protein), likely because of slightly higher immunoreactivity of the polyclonal antibody to detect recombinant TSPO than the native TSPO in human brains. For comparison, levels of TSPO protein in human adrenal tissue samples (n = 3) were 1.34 (0.19) ng/µg protein using the rabbit monoclonal antibodies.

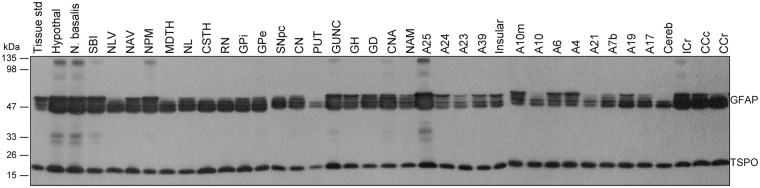

Regional brain distribution of TSPO and GFAP protein in the human

Brains from six middle aged (47–49 years) subjects were examined for regional distribution of TSPO as compared to that of the commonly used astrocyte marker GFAP (see Figure 2 for representative immunoblots). Upon longer exposure, regions with higher levels of GFAP also showed high and low molecular weight GFAP immunoreactive species (see Tong et al.70), which were not included in the quantification. One-way ANOVA revealed significant differences among the 37 brain regions in levels of both TSPO (F36,180 = 4.3, p < 0.0001) and GFAP (F36,180 = 3.6, p < 0.0001) (Table 2). However, the heterogeneity was mainly driven by higher levels of both proteins in a few small brain areas including hypothalamus, subgenual prefrontal cortex (Brodmann A25), hippocampal uncus, and nucleus basalis. In analysis of 15 grouped and averaged brain areas (TSPO [F14,75 = 4.2, p < 0.0001] and GFAP [F14,75 = 5.4, p < 0.0001]), although differences among major brain regions of thalamus, hippocampus/amygdala, cerebral/cerebellar cortices, and striatum were small (Table 2), the average thalamic values of both proteins were significantly higher than those of striatum and cerebellar cortex (p < 0.05, post hoc LSD tests). White matter regions had a level of TSPO similar to those of the grey matter regions. In contrast, GFAP levels in the white matter regions were significantly higher than those of the striatum, cerebellar cortex, and many of the cerebral cortices (frontal, temporal and parietal) (p < 0.05, post hoc LSD tests). There was a significant positive correlation between levels of TSPO and GFAP among the brain regions examined (r = 0.72, p < 0.0001). In particular, brain regions including hypothalamus, subgenual prefrontal cortex, hippocampal uncus, and nucleus basalis had high levels of both proteins whereas the opposite was observed for regions like cerebellar cortex and striatum.

Figure 2.

Representative immunoblots of the regional distribution of TSPO and GFAP in autopsied human brain. A23: cingulate gyrus posterior; A24: cingulate gyrus anterior; A25: paraolfactory/subgenual gyrus; CCc: corpus callosum caudal; CCr: corpus callosum rostral; cereb: cerebellar cortex; CN: caudate; CNA: hippocampal Ammon’s horn; CSTH: subthalamic nucleus; GD: dentate gyrus; GH: hippocampal gyrus; GPe: globus pallidus external; GPi: globus pallidus internal; GUNC: gyrus of uncus; hypothal: hypothalamus; ICr: internal capsule rostral; MDTH: mediodorsal thalamus; NAM: amygdala; NAV: anterior ventral nucleus of thalamus; N. basalis: nucleus basalis; NL: nucleus lateralis of thalamus; NLV: lateral ventral nucleus of thalamus; NPM: medial pulvinar of thalamus; PUT: putamen; RN: red nucleus; SBI: substantia innominata; SNpc: substantia nigra pars compacta.

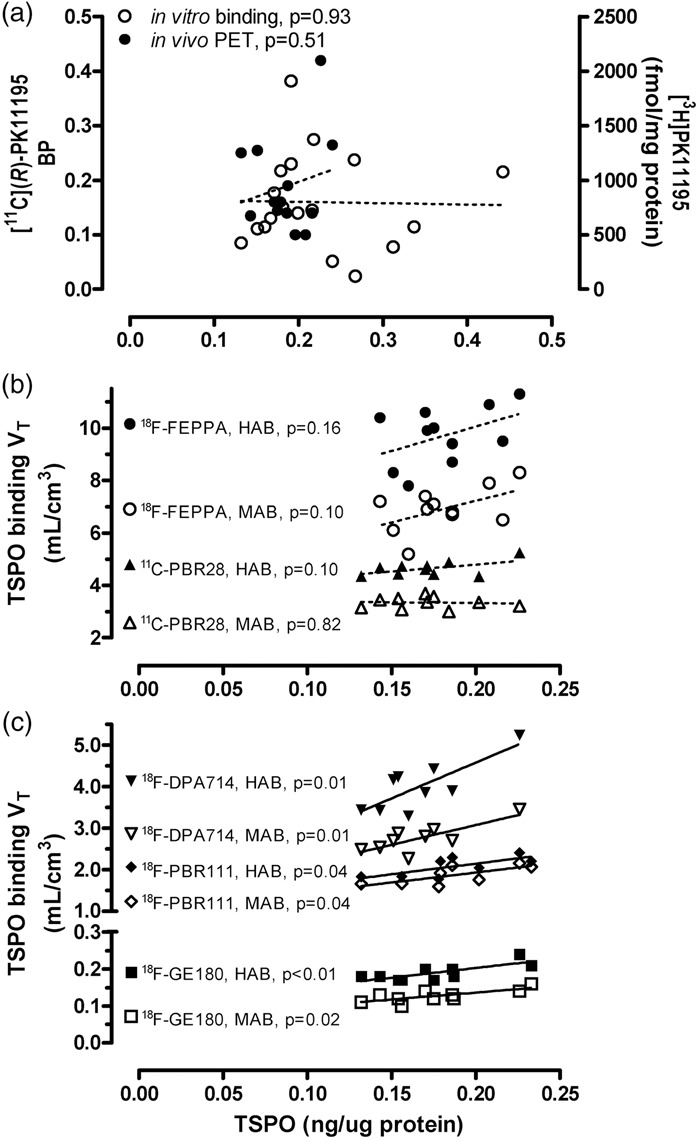

Correlations between regional TSPO protein concentrations and binding levels reported in in vitro and in vivo studies in the literature

Postmortem brain comparisons

We first examined the correlations between our regional TSPO protein distribution data and those of regional binding density determined by autoradiography or radioligand binding assay using the prototypical TSPO ligands [3H]PK1119537,38,43 or [3H]Ro5-486437 in autopsied human brain reported in the literature. No significant correlation was observed (e.g. see Figure 3(a) for the correlation with binding data by Doble et al 1987:38 y = 827-120.5x, r = −0.02, p = 0.93, n = 18). Notably, higher levels of binding were reported for cerebral cortical areas, despite lower TSPO protein levels, as compared to some subcortical regions including globus pallidus and midbrain (substantia nigra and red nucleus)37,38,43; the subgenual prefrontal cortex, i.e. the parolfactory subcallosal area, had a high concentration of TSPO protein but was reported to have a low level of binding for [3H]PK11195.38 In addition, the white matters had significant levels of TSPO protein but were reported to have only non-specific binding for [3H]PK1119538 (but see Banati et al.20). One study reported regional autoradiography binding data using a second generation TSPO ligand [125I]desmethoxy-DAA1106, with lowest binding observed in the thalamus whereas a high level of binding in the white matter,76 contrary to our observation for TSPO protein, although it should be noted that TSPO distribution in sub-nuclei of thalamus can be heterogeneous (Table 2; see also Doble et al.38).

Figure 3.

Correlations (Pearson) between regional protein levels of TSPO determined in this study vs. outcome measures of binding reported in the literature (p < 0.05 for solid lines and p > 0.05 for dashed lines). To assess the correlation between TSPO protein vs. TSPO binding amongst different brain areas, the following regions were employed, with subregional averages when necessary: thalamus, midbrain, globus pallidus, hippocampus, amygdala, cerebral cortical areas (cingulate, insula, frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital cortices), cerebellar cortex, and striatum (caudate and putamen). (a) TSPO protein versus [3H]PK11195 binding density determined by autoradiography in autopsied human brain reported by Doble et al.38 and [11C](R)-PK11195 binding potential acquired by positron emission tomography (PET) reported by Cagnin et al.21 Note the lack of correlation between the regional distribution of TSPO protein in our autopsied human brain study vs. the regional distribution of binding of the first generation TSPO tracer, PK11195. (b, c) TSPO protein regional distribution in autopsied human brain versus PET total distribution volume (VT) of five second generation TSPO radiotracers that are influenced by the single nucleotide genetic polymorphism (rs6971, HAB-high affinity binder and MAB-mixed affinity binder), including [18F]-FEPPA reported by Atwells et al.,27 [11C]PBR28 reported by Rizzo et al.,23 [18F]DPA-714 reported by Lavisse et al.,30 [18F]PBR-111 reported by De Picker et al.,32 and [18F]GE-180 reported by Fan et al.34 Note that in contrast to the lack of correlation with the first generation ligand, there was positive (r = 0.72–0.79, p < 0.05) or a trend for a positive correlation (r = 0.45–0.55, p = 0.10–0.16) between the regional distribution of TSPO protein in autopsied brain vs. those of binding of the second generation tracers in PET imaging studies, with the exception of [11C]PBR28 in MAB (r = −0.09, p = 0.82).

PET imaging comparisons

The commonly used PET outcome measure for the first generation TSPO ligand [11C](R)-PK11195 is binding potential, determined with different reference tissue models. Correlations between reported regional [11C](R)-PK11195 binding potential and TSPO protein levels were generally poor (e.g. see Figure 3(a) for the correlation with PET data by Cagnin et al.:21 y = 0.086 + 0.55x, r = 0.20, p = 0.51, n = 13). In particular, most of the studies reported higher [11C](R)-PK11195 binding potential in the putamen (0.08–0.26) as compared to the hippocampus (0.05–0.14) and cerebral cortical areas (0.03–0.16),21,53,77–79 which is in contradistinction with that for TSPO protein levels in which the putamen had among the lowest levels of TSPO protein.

Imaging the second generation TSPO radiotracers is dependent on a single nucleotide genetic polymorphism (rs6971, high binder HAB vs. mixed binder MAB, with low binder LAB generally not scanned).80,81 Among the many second generation TSPO ligands, we examined those PET studies reporting the binding parameter VT (total distribution volume) that was assessed in a wide range of brain regions in both HAB and MAB and observed that the common pattern of binding ranking order in major grey matter areas follows the rank of thalamus, midbrain > hippocampus, cerebral cortices >striatum,23,27,30,32,34 in general agreement with TSPO protein distribution in autopsied brain. As shown in Figure 3(b) and (c) for five representative TSPO ligands with different brain binding characteristics, correlations between VT and regional TSPO protein levels were significant and positive for [18F]DPA-71430 (HAB: y = 1.1 + 17.2x, r = 0.79, p = 0.01; MAB: y = 1.2 + 9.53x, r = 0.79, p = 0.01; n = 9), [18F]-PBR11132 (HAB: y = 1.1 + 5.1x, r = 0.72, p = 0.04; MAB: y = 0.97 + 4.8x, r = 0.72, p = 0.04; n = 8), and [18F]GE-18034 (HAB: y = 0.098 + 0.52x, r = 0.77, p = 0.009; MAB: y = 0.06 + 0.38x, r = 0.74, p = 0.015; n = 10), with some non-significant trends for [18F]-FEPPA27 (HAB: y = 6.3 + 18.7x, r = 0.45, p = 0.16; MAB: y = 3.9 + 16.4x, r = 0.52, p = 0.10; n = 11) and [11C]PBR2823 (HAB: y = 3.70 + 5.55x, r = 0.55, p = 0.10; MAB: y = 3.46-0.67x, r = −0.09, p = 0.82; n = 10). There was no significant difference between HAB and MAB in the slope of these correlations. Notably, TSPO PET imaging generally underestimated regional differences in TSPO protein levels (all y-intercept > 0 with the exception of [18F]DPA-714 in HAB30).

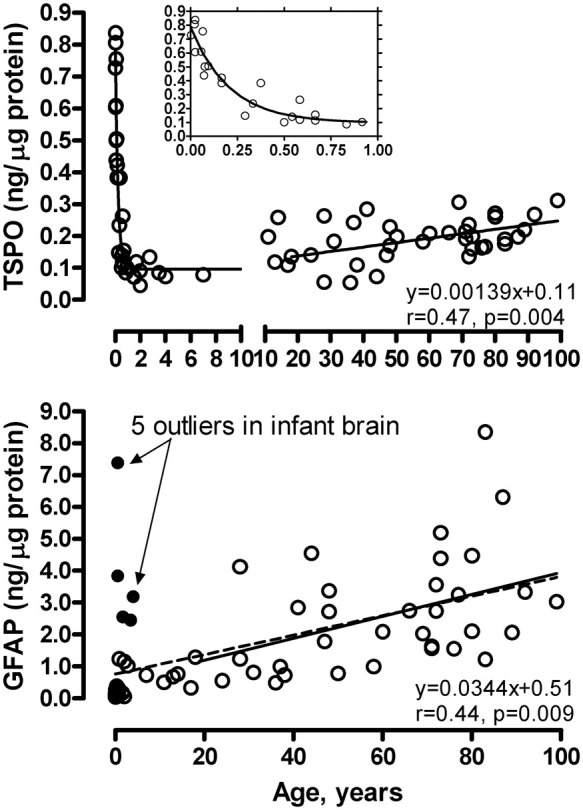

Changes in levels of TSPO and GFAP in human brain development and aging

As shown in Figure 4, TSPO levels were high in the newborn brain (0.74 [0.10] ng/µg protein, within 10 days of birth) but declined approximately exponentially during the first three months of age and remained at a low level until early adulthood, at which TSPO brain levels increased slowly but significantly with adult aging and senescence. The rate of TSPO increase was 0.0014 ng/µg protein/year or 10% per decade (18 to 99 years, r = 0.47, n = 35, p = 0.004). In contrast, levels of the astroglial marker GFAP were low in the newborn brain (0.07 [0.02] ng/µg protein, within 10 days of birth) but increased steadily throughout life. Five subjects aged 6 months to 4 years, for unknown reasons, had a GFAP level (2.5–7.4 ng/µg protein) more than six standard deviations above the mean value of the rest of the subjects under 4 years of age (n = 24) and thus were excluded from the correlation analysis (Figure 4) [note: the five subjects had a TSPO level that was not unusual]. During adulthood, the rate of GFAP increase was 0.034 ng/µg protein/year or 30% per decade (18–99 years, r = 0.44, n = 35, p = 0.009). GFAP had a significantly greater rate of increase during adult brain aging and senescence than that of TSPO (p < 0.05). We found no significant correlation between levels of TSPO and GFAP during adult brain aging (p > 0.05). Given some PET findings of diurnal changes of TSPO binding with increased VT from morning to afternoon in the same day test–retest setting,82,83 we examined the possible confound of time of death on TSPO protein levels. As shown in Supplement Figure 2, there was no clear pattern of circadian changes of either TSPO or GFAP in the 24 adult cases having information on time of death.

Figure 4.

Aging and neonatal developmental changes of levels of TSPO and GFAP in autopsied human brain. The inset shows enlarged portion below 1 year of age for TSPO. The linear correlations are for adults (18–99 years). The dashed line in the GFAP graph shows the linear correlation in the full age range (21 hours to 99 years of age) excluding five outliers (solid circles). Note high levels of TSPO during first three months of birth, its exponential drop thereafter, and slow increase during adult aging and senescence; in contrast, GFAP levels were low at birth, other than in the five outliers, and increased steadily throughout life.

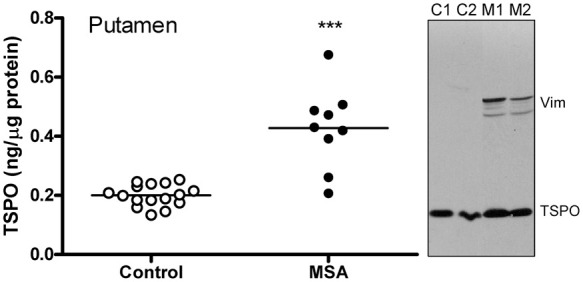

Increased TSPO levels in putamen of patients with MSA

As shown in Figure 5, levels of TSPO were, as expected, significantly increased on average by 114% (95% CI 61–166) in the degenerating putamen of patients with MSA (0.43 [0.14] ng/µg protein), employed as a positive control in which brain gliosis is present, as compared to the controls (0.20 [0.04] ng/µg protein) (two-tailed independent t-test, Hedges’ g = 2.6, 95% CI 1.5–3.7). However, among the MSA patients, there was no significant correlation between increased TSPO levels and those of other markers of microglia including HLA-DRα (TAL.1B5, + 678%), HLA-DR/DP/DQβ (CR3/43, + 712%) and glucose transporter-5 (+28%) or astrocytes including GFAP (+163%), vimentin (+1614%; see also Figure 5 for representative blots), heat shock protein-27 (+455%) and monoamine oxidase-B (+83%). Indeed, no significant correlation was observed among increased levels of the microglial markers (TSPO, HLA-DRα, HLA-DR/DP/DQβ and GLUT5) in MSA putamen whereas significant positive correlations amongst increased levels of astroglial markers (GFAP, vimentin, HSP-27 and MAO-B) were reported previously.61,62,67,70

Figure 5.

Increased levels of TSPO protein in putamen of patients with multiple system atrophy (MSA) as compared to control subjects. ***p < 0.001 (two-tailed t-test). Also shown are representative immunoblots of TSPO and an astroglial marker vimentin probed at the same time. Note greater increases in levels of vimentin as compared to that of TSPO in MSA (M1 and M2) versus controls (C1 and C2).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first detailed quantitative examination of several TSPO protein characteristics (concentration, aging, regional distribution) in autopsied human brain.

TSPO is an abundant protein in the human brain

As the major component of the peripheral benzodiazepine binding site, TSPO is reported to be less abundant in the brain than in the peripheral organs, e.g. kidney and adrenal gland.3,4,7,39,84 However, the absolute level of TSPO protein in brain is uncertain, with reported concentrations of the peripheral benzodiazepine binding site in the human brain estimated by saturation binding assays varying between <100 and ∼4000 fmol/mg tissue protein (assuming a membrane to homogenate protein ratio of 0.5 for data reported in fmol/mg membrane protein and assuming a protein/tissue ratio of 0.05 for data reported in fmol/mg wet tissue85; see Supplementary Table 1).37–50 The variation possibly reflects actual differences in the binding sites for the different ligands (e.g. [3H]Ro5-4864 vs. [3H]PK11195),37 the uncertainty in non-specific binding of the probes employed (mostly by [3H]PK11195; but also by second generation ligands [3H]DAA110648,49 and [3H]PBR2846), different experimental binding protocols employed with the same probe (e.g. 4 vs. 37℃46 or room temperature39 incubation; see Supplementary Table 1 and also46), and also variable conditions of the postmortem human tissue preparations for radioligand binding. We employed a quantitative immunoblotting approach with specificity of the antibody confirmed by several criteria including mass of the protein band detected, subcellular and regional distribution, cross-examination with several antibodies of different immunoreactivities, purified recombinant proteins, and positive control of MSA putamen with well-known microglial activation. One limitation of using recombinant TSPO protein for calibration is that the recombinant protein could have different immunoreactivities due to different post-translational modifications than the native TSPO. Indeed, the polyclonal PA5-75544 gave a TSPO concentration 44% lower than that obtained with the monoclonal antibodies, apparently due to its relatively higher reactivity to the recombinant TSPO. PA5-75544 also showed different immunoreactivities against TSPO from brain versus that from adrenal gland, again suggesting organ specific post-translational modification of TSPO protein, which warrants further detailed studies. However, two different monoclonal antibodies provided similar results and the obtained TSPO protein concentrations (0.13–0.44 µg/mg protein homogenate, equivalent to 7,000–24,000 fmol/mg protein or 350–1200 nM assuming a protein/tissue ratio of 0.05 and a unit weight of 1 g/mL)85 are 2 to 70 fold higher than expected from previous binding assays in the human brain (<100–4000 fmol/mg tissue protein; Supplementary Table 1). The reason for the discrepancy between the TSPO protein concentration and Bmax estimates by binding of the TSPO ligands could be explained by TSPO being only one part of the ligand binding site on the outer membrane of mitochondria as suggested for Ro5-4864,86 with several other proteins including the voltage-dependent anion channels and the adenine nucleotide carrier possibly also involved (but see Joseph-Liauzun et al.87). Alternatively, oligomers of TSPO75 might provide a binding site for a single molecule of PK11195 or congener—or possibly not all TSPO proteins might be available for binding because of endogenous substrate/ligand occupying the binding sites,88 a denatured state of TSPO due to loss of mitochondrial membrane potential postmortem, or presence of a reserve pool of TSPO, reminiscent of the situation in reconstituted TSPO proteoliposome.89 The apparent temperature sensitivity of the in vitro [3H]PK11195 binding assay in human brain tissue (Supplementary Table 1; but see Benavides et al.4 for the lack of temperature sensitivity in rat brain), with decreased affinity but also higher Bmax obtained at higher incubation temperature (unlike that for serotonin transporter binding),90 may suggest that TSPO alone is in a dynamically unstable state under physiological temperature; self-association, interaction with other proteins, or engagement of endogenous substrates might stabilize its structure and thus influence ligand binding, similar to the situation of receptor-G protein interaction.91

One potential limitation of our study is the lack of rs6971 genotype for our subjects therefore it is unknown whether the genetic variation that affects binding of many second generation TSPO ligands80,81 also influences TSPO protein levels in the brain. A recent study suggested that rs6971 might slightly destabilize TSPO protein in cultured human fibroblast cells.92 Although the low and high affinity binders did not show significant difference in Bmax or Kd for [3H]PK11195 in human brain,46 further studies would be required to confirm whether rs6971 does or does not influence brain TSPO protein levels.

TSPO in human brain development and aging

The high levels of TSPO in neonatal brain and its precipitous decline within the first few months of birth are remarkable. There is still no consensus on the physiological role of TSPO although many functions have been proposed throughout the years including cholesterol and porphyrin transportation into mitochondria, regulation of mitochondria respiration, permeability, free radical production and apoptosis.1,13–17 Many of these functions were studied in cultured cells of gonadal and adrenal/renal origin, with the role of TSPO in brain much less examined. Recent data show that TSPO is also highly expressed in neural stem and neuronal precursor cells in embryonic and neonatal brain of mice,93 suggesting that TSPO might be involved in brain development and neuronal differentiation. However, this does not “explain” the substantial postnatal loss of TSPO within a few months of birth when the brain is still growing rapidly. For comparison, GFAP, the intermediate filament protein also expressed by neuronal precursor cells that are of astroglial origins, follows a different expression trajectory from TSPO in neonatal brain. Given a putative key role of TSPO in the regulation of mitochondria respiration and free radical production94,95 and unusual oxidative stress faced by the newborn,96,97 it is not unreasonable to predict that a high level of TSPO in newborn brain might perhaps have a neuroprotective function. Future studies will be needed to examine more carefully the localization of TSPO in the neonatal human brain, which may reveal more details about the functions of TSPO in the brain. In this respect, it appears that the transient high levels of TSPO in newborn brains might not reflect changes in numbers of a particular population of neural cells including microglia.98

Unlike the situation in neonates, aging of the brain is associated with increasing protein levels of TSPO and GFAP although the magnitude of age-related increase is modest and less for TSPO than for GFAP in our study. Our finding on TSPO protein is also in agreement with a report of an age-related increase in TSPO gene expression in human dorsolateral prefrontal cortex,99 which was also less prominent than that for GFAP. The observation of a significant positive correlation between age and GFAP levels in the frontal cortex confirms and extends our previous report in other brain regions in adult brains.61,67 For TSPO, PET imaging studies with different radiotracers have produced mixed results (no-significant change32,55,56 and increase51–54) on age-related changes in TSPO binding in the human. One possible explanation for the ambiguity is the small effect size of age-related increase we found for TSPO protein and generally limited number of subjects and sometimes also limited age range32,53,54 examined in PET imaging studies.

TSPO protein vs. PET regional brain distribution

Interestingly, the regional distribution of TSPO is generally similar to that of GFAP in adult human brain, suggesting co-regulation of the activities of microglia and astrocytes. This is not surprising given their important orchestrated roles in maintaining brain homeostasis and synaptic function.100 Limited data also suggest that astrocytes can express TSPO in both normal and pathological human brains.65 Further immunohistochemical studies would be needed to address the regional extent of this co-localization in normal conditions.

Comparison of the regional distribution of TSPO protein and PET TSPO binding showed that the second generation TSPO ligands generally performed similarly to each other and better than that of the first generation prototypical ligand [11C](R)-PK11195 in the in vitro vs. in vivo correlations, despite a narrow window of TSPO protein distribution in major brain areas of thalamus, hippocampus, cerebral/cerebellar cortices, and striatum; this provides some further “validation” of the new generation of TSPO radiotracers. The modest correlations and general underestimation of regional contrast by PET TSPO binding should be interpreted with caution given many technical limitations. For example, regional distribution correlations were difficult to achieve given the limited extent of differences in TSPO protein levels amongst the different brain areas. This might also be related to relatively low brain uptake of the TSPO radiotracers in healthy control subjects (with peak standard uptake values generally less than 2), making it less reliable to establish a normal distribution pattern, limited PET spatial resolution and partial volume effects (e.g. cerebral vs. cerebellar cortices), combined with noise sensitivity of the particular radiotracer and modeling approach. Another contributing factor might be the free and non-specific binding component (VND) of the two-tissue compartment model. Blocking studies showed that VND accounts for 12% (HAB) to 23% (MAB) of total whole brain binding of [11C]DPA-713,101 46% (HAB) to 67% (MAB) of [11C]PBR28102 (see also Sridharan et al.103) assuming the same level of VND in HAB and MAB (note: lower VND was reported for [11C]PBR28 by using a different modelling approach104 and by a recent study using a different blocker105), 43% (HAB) to 80% (MAB) of [18F]GE-180 in patients with multiple sclerosis,103 and 57% (HAB and MAB) of [11C](R)-PK11195,101 suggesting that non-specific binding explains at least part of the contrast loss in vivo. Other factors might include inherent in vivo vs. in vitro differences so that not all TSPO proteins are available for in vivo binding of the ligand at a tracer dose, e.g. by engagement of an endogenous TSPO ligand, differential post-translational modification, and dynamic state of TSPO polymerization and association with other proteins. PET outcome measures (BP or VT) obtained at a single tracer dose are determined by both target concentration (Bmax) and affinity (Kd) of the radiotracer, i.e. Bmax/Kd, which can be influenced by the many above-mentioned in vivo variables. Thus, a regional difference in Kd may not be unexpected in vivo. It should also be acknowledged that our immunoblotting study was limited in anatomical extent of tissue sampling, in particular in sub-regionally heterogeneous brain areas, e.g. thalamus and hippocampus. The subregions are not equal in volume; thus, simple mathematical average of protein levels in the subregions may not represent the actual overall concentration. Nevertheless, our previous studies of serotonin transporter and monoamine oxidase-A and -B with similar approaches showed that brain regional PET radiotracer binding in vivo can correlate well and in proportion to the target concentrations determined in vitro by Western immunoblotting.68,106

TSPO and MSA

Our finding of increased (by 114%) levels of TSPO in degenerating putamen of patients with MSA, used as a positive disease control in which brain gliosis and increased number of microglia and astrocytes107 are present, adds to the literature support for the usefulness of TSPO as a marker of gliosis and is consistent with the PET finding in MSA using [11C](R)-PK11195.108 Interestingly, there was no significant correlation among elevated levels of the microglial markers including TSPO, HLA-DRα, HLA-DR/DP/DQβ and GLUT5 or between microglial and astroglial markers, despite significant positive correlations among increased expression of astroglial markers (GFAP, vimentin, HSP-27 and MAO-B)62; this suggests the possibility of individual heterogeneity in microglial response and that TSPO may label a different subset of activated glial cells. The magnitude of TSPO change (+114%) was smaller than that of HLA-DRα (+678%), HLA-DR/DP/DQβ (+712%), vimentin (+1614%), and heat shock protein-27 (+455%), at a similar level to that of GFAP (+163%) and monoamine oxidase-B (+83%), and larger than that of glucose transporter-5 (+28%). This might be related to baseline levels of the glial markers, with those abundant in healthy controls (GFAP, MAO-B, GLUT5, and TSPO) expected to be less sensitive to detect an increase in pathological conditions than those rare at baseline. Further detailed immunohistochemical investigation would be needed to address the cellular and subcellular localization of TSPO protein in MSA and to establish the extent TSPO is selectively associated with activated microglia in this condition.

Implications for TSPO brain imaging

The TSPO PET imaging literature has suggested that TSPO levels in normal human brain are low to absent (e.g. see literature20,77,109–111); this was perhaps driven by observations of generally low PET TSPO binding in healthy human brain and by very low PET TSPO binding and barely detectable TSPO protein levels in healthy rodent brains.112 Although there may be different explanations for the low brain TSPO binding in vivo in the human for the available TSPO radiotracers, our findings raise the possibility of the existence of a large reserve pool of TSPO protein that is normally not available for tracer binding. Speculatively, activation or deactivation of the TSPO reserve pool could be another mechanism for TSPO binding changes observed in some neuropsychiatric conditions. The observed regional brain correlations, albeit modest, between TSPO protein levels and binding of multiple second generation TSPO ligands of different chemical structures, unique non-specific binding profiles, and variable brain availabilities, also point to a reconfirmation of their common target.

In summary, we determined TSPO protein concentrations in human brain and its developmental and aging changes. The correlation between regional brain distribution of TSPO protein determined postmortem and binding of the second generation TSPO radiotracers in living humans provides further validation of the PET outcome measures of TSPO binding. Our finding of higher than expected brain TSPO protein concentrations suggests that not all TSPO protein might be available for ligand binding.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Concentration, distribution, and influence of aging on the 18 kDa translocator protein in human brain: Implications for brain imaging studies by Junchao Tong, Belinda Williams, Pablo M. Rusjan, Romina Mizrahi, Jean-Jacques Lacapère, Tina McCluskey, Yoshiaki Furukawa, Mark Guttman, Lee-Cyn Ang, Isabelle Boileau, Jeffrey H Meyer and Stephen J Kish in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by grants from NIH NIDA DA040066 and DA07182.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions

JT, IB and SJK designed the study; JT, BW and TM were responsible for data collection and analysis; JT, JHM and SJK drafted the initial manuscript; PMR, RM, JJL, TM, YF, MG, LCA made substantial contribution to the data interpretation. All authors critically revised the article. All authors approved the final version.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this paper can be found at the journal website: http://journals.sagepub.com/home/jcb

References

- 1.Papadopoulos V, Baraldi M, Guilarte TR, et al. Translocator protein (18kDa): new nomenclature for the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor based on its structure and molecular function. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2006; 27: 402–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braestrup C, Albrechtsen R, Squires RF. High densities of benzodiazepine receptors in human cortical areas. Nature 1977; 269: 702–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schoemaker H, Bliss M, Yamamura HI. Specific high-affinity saturable binding of [3H] R05-4864 to benzodiazepine binding sites in the rat cerebral cortex. Eur J Pharmacol 1981; 71: 173–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benavides J, Quarteronet D, Imbault F, et al. Labelling of “peripheral-type” benzodiazepine binding sites in the rat brain by using [3H]PK 11195, an isoquinoline carboxamide derivative: kinetic studies and autoradiographic localization. J Neurochem 1983; 41: 1744–1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schoemaker H, Morelli M, Deshmukh P, et al. [3H]Ro5-4864 benzodiazepine binding in the kainate lesioned striatum and Huntington’s diseased basal ganglia. Brain Res 1982; 248: 396–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schoemaker H, Smith TL, Yamamura HI. Effect of chronic ethanol consumption on central and peripheral type benzodiazepine binding sites in the mouse brain. Brain Res 1983; 258: 347–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le Fur G, Perrier ML, Vaucher N, et al. Peripheral benzodiazepine binding sites: effect of PK 11195, 1-(2-chlorophenyl)-N-methyl-N-(1-methylpropyl)-3-isoquinolinecarboxamide. I. In vitro studies. Life Sci 1983; 32: 1839–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kish SJ, Sperk G, Hornykiewicz O. Alterations in benzodiazepine and GABA receptor binding in rat brain following systemic injection of kainic acid. Neuropharmacology 1983; 22: 1303–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Owen F, Poulter M, Waddington JL, et al. [3H]R05-4864 and [3H]flunitrazepam binding in kainate-lesioned rat striatum and in temporal cortex of brains from patients with senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. Brain Res 1983; 278: 373–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benavides J, Fage D, Carter C, et al. Peripheral type benzodiazepine binding sites are a sensitive indirect index of neuronal damage. Brain Res 1987; 421: 167–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Myers R, Manjil LG, Cullen BM, et al. Macrophage and astrocyte populations in relation to [3H]PK 11195 binding in rat cerebral cortex following a local ischaemic lesion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1991; 11: 314–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banati RB, Myers R, Kreutzberg GW. PK (‘peripheral benzodiazepine')-binding sites in the CNS indicate early and discrete brain lesions: microautoradiographic detection of [3H]PK11195 binding to activated microglia. J Neurocytol 1997; 26: 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papadopoulos V, Fan J, Zirkin B. Translocator protein (18 kDa): an update on its function in steroidogenesis. J Neuroendocrinol 2018; 30: e12500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guilarte TR, Loth MK, Guariglia SR. TSPO finds NOX2 in microglia for redox homeostasis. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2016; 37: 334–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selvaraj V, Tu LN. Current status and future perspectives: TSPO in steroid neuroendocrinology. J Endocrinol 2016; 231: R1–R30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gut P, Zweckstetter M, Banati RB. Lost in translocation: the functions of the 18-kD translocator protein. Trends Endocrinol Metab: TEM 2015; 26: 349–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sileikyte J, Blachly-Dyson E, Sewell R, et al. Regulation of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore by the outer membrane does not involve the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor (Translocator Protein of 18 kDa (TSPO)). J Biol Chem 2014; 289: 13769–13781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stocco DM, Zhao AH, Tu LN, et al. A brief history of the search for the protein(s) involved in the acute regulation of steroidogenesis. Mol Cellular Endocrinol 2017; 441: 7–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owen DR, Fan J, Campioli E, et al. TSPO mutations in rats and a human polymorphism impair the rate of steroid synthesis. Biochem J 2017; 474: 3985–3999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banati RB, Newcombe J, Gunn RN, et al. The peripheral benzodiazepine binding site in the brain in multiple sclerosis: quantitative in vivo imaging of microglia as a measure of disease activity. Brain 2000; 123: 2321–2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cagnin A, Brooks DJ, Kennedy AM, et al. In-vivo measurement of activated microglia in dementia. Lancet 2001; 358: 461–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown AK, Fujita M, Fujimura Y, et al. Radiation dosimetry and biodistribution in monkey and man of 11C-PBR28: a PET radioligand to image inflammation. J Nucl Med 2007; 48: 2072–2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rizzo G, Veronese M, Tonietto M, et al. Kinetic modeling without accounting for the vascular component impairs the quantification of [(11)C]PBR28 brain PET data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2014; 34: 1060–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson AA, Garcia A, Parkes J, et al. Radiosynthesis and initial evaluation of [18F]-FEPPA for PET imaging of peripheral benzodiazepine receptors. Nucl Med Biol 2008; 35: 305–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Setiawan E, Wilson AA, Mizrahi R, et al. Role of translocator protein density, a marker of neuroinflammation, in the brain during major depressive episodes. JAMA Psychiatr 2015; 72: 268–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suridjan I, Pollock BG, Verhoeff NP, et al. In-vivo imaging of grey and white matter neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease: a positron emission tomography study with a novel radioligand, [F]-FEPPA. Mol Psychiatr 2015; 20: 1579–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Attwells S, Setiawan E, Wilson AA, et al. Inflammation in the neurocircuitry of obsessive-compulsive disorder. JAMA Psychiatr 2017; 74: 833–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Setiawan E, Attwells S, Wilson AA, et al. Association of translocator protein total distribution volume with duration of untreated major depressive disorder: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Psychiatr 2018; 5: 339–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.James ML, Fulton RR, Vercoullie J, et al. DPA-714, a new translocator protein-specific ligand: synthesis, radiofluorination, and pharmacologic characterization. J Nucl Med 2008; 49: 814–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lavisse S, Garcia-Lorenzo D, Peyronneau MA, et al. Optimized quantification of translocator protein radioligand (1)(8)F-DPA-714 uptake in the brain of genotyped healthy volunteers. J Nucl Med 2015; 56: 1048–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fookes CJ, Pham TQ, Mattner F, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of substituted [18F]imidazo[1,2-a]pyridines and [18F]pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidines for the study of the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor using positron emission tomography. J Med Chem 2008; 51: 3700–3712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Picker L, Ottoy J, Verhaeghe J, et al. State-associated changes in longitudinal [(18)F]-PBR111 TSPO PET Imaging of psychosis patients: evidence for the accelerated ageing hypothesis? Brain Behav Immun 2019; 77: 46–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dickens AM, Vainio S, Marjamaki P, et al. Detection of microglial activation in an acute model of neuroinflammation using PET and radiotracers 11C-(R)-PK11195 and 18F-GE-180. J Nucl Med 2014; 55: 466–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fan Z, Calsolaro V, Atkinson RA, et al. Flutriciclamide (18F-GE180) PET: first-in-human pet study of novel third-generation in vivo marker of human translocator protein. J Nucl Med 2016; 57: 1753–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cumming P, Burgher B, Patkar O, et al. Sifting through the surfeit of neuroinflammation tracers. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2018; 38: 204–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turkheimer FE, Rizzo G, Bloomfield PS, et al. The methodology of TSPO imaging with positron emission tomography. Biochem Soc Transact 2015; 43: 586–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rao VL, Butterworth RF. Characterization of binding sites for the omega3 receptor ligands [3H]PK11195 and [3H]RO5-4864 in human brain. Eur J Pharmacol 1997; 340: 89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doble A, Malgouris C, Daniel M, et al. Labelling of peripheral-type benzodiazepine binding sites in human brain with [3H]PK 11195: anatomical and subcellular distribution. Brain Res Bull 1987; 18: 49–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Broaddus WC, Bennett JP, Jr. Peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptors in human glioblastomas: pharmacologic characterization and photoaffinity labeling of ligand recognition site. Brain Res 1990; 518: 199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lavoie J, Layrargues GP, Butterworth RF. Increased densities of peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptors in brain autopsy samples from cirrhotic patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology 1990; 11: 874–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diorio D, Welner SA, Butterworth RF, et al. Peripheral benzodiazepine binding sites in Alzheimer's disease frontal and temporal cortex. Neurobiol Aging 1991; 12: 255–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Awad M, Gavish M. Peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptors in human cerebral cortex, kidney, and colon. Life Sci 1991; 49: 1155–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kurumaji A, Wakai T, Toru M. Decreases in peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptors in postmortem brains of chronic schizophrenics. J Neural Transmiss 1997; 104: 1361–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Messmer K, Reynolds GP. Increased peripheral benzodiazepine binding sites in the brain of patients with Huntington's disease. Neurosci Lett 1998; 241: 53–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sauvageau A, Desjardins P, Lozeva V, et al. Increased expression of “peripheral-type” benzodiazepine receptors in human temporal lobe epilepsy: implications for PET imaging of hippocampal sclerosis. Metab Brain Dis 2002; 17: 3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Owen DR, Howell OW, Tang SP, et al. Two binding sites for [3H]PBR28 in human brain: implications for TSPO PET imaging of neuroinflammation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2010; 30: 1608–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Venneti S, Bonneh-Barkay D, Lopresti BJ, et al. Longitudinal in vivo positron emission tomography imaging of infected and activated brain macrophages in a macaque model of human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis correlates with central and peripheral markers of encephalitis and areas of synaptic degeneration. Am J Pathol 2008. a; 172: 1603–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Venneti S, Wang G, Wiley CA. The high affinity peripheral benzodiazepine receptor ligand DAA1106 binds to activated and infected brain macrophages in areas of synaptic degeneration: implications for PET imaging of neuroinflammation in lentiviral encephalitis. Neurobiol Dis 2008. b; 29: 232–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Venneti S, Wang G, Nguyen J, et al. The positron emission tomography ligand DAA1106 binds with high affinity to activated microglia in human neurological disorders. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2008; 67: 1001–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Venneti S, Lopresti BJ, Wang G, et al. PK11195 labels activated microglia in Alzheimer's disease and in vivo in a mouse model using PET. Neurobiol Aging 2009; 30: 1217–1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gulyas B, Vas A, Toth M, et al. Age and disease related changes in the translocator protein (TSPO) system in the human brain: positron emission tomography measurements with [11C]vinpocetine. Neuroimage 2011; 56: 1111–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schuitemaker A, van der Doef TF, Boellaard R, et al. Microglial activation in healthy aging. Neurobiol Aging 2012; 33: 1067–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kumar A, Muzik O, Shandal V, et al. Evaluation of age-related changes in translocator protein (TSPO) in human brain using (11)C-[R]-PK11195 PET. J Neuroinflam 2012; 9: 232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guo Q, Colasanti A, Owen DR, et al. Quantification of the specific translocator protein signal of 18F-PBR111 in healthy humans: a genetic polymorphism effect on in vivo binding. J Nucl Med 2013; 54: 1915–1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Suridjan I, Rusjan PM, Voineskos AN, et al. Neuroinflammation in healthy aging: a PET study using a novel translocator protein 18kDa (TSPO) radioligand, [(18)F]-FEPPA. Neuroimage 2014; 84: 868–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yokokura M, Terada T, Bunai T, et al. Depiction of microglial activation in aging and dementia: Positron emission tomography with [(11)C]DPA713 versus [(11)C](R)PK11195. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017; 37: 877–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Benavides J, Cornu P, Dennis T, et al. Imaging of human brain lesions with an omega 3 site radioligand. Ann Neurol 1988; 24: 708–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chiu WZ, Donker Kaat L, Boon AJW, et al. Multireceptor fingerprints in progressive supranuclear palsy. Alzheimer's Res Ther 2017; 9: 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McGeer EG, Singh EA, McGeer PL. Peripheral-type benzodiazepine binding in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Dis 1988; 2: 331–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pazos A, Cymerman U, Probst A, et al. “Peripheral” benzodiazepine binding sites in human brain and kidney: autoradiographic studies. Neurosci Lett 1986; 66: 147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tong J, Fitzmaurice P, Furukawa Y, et al. Is brain gliosis a characteristic of chronic methamphetamine use in the human? Neurobiol Dis 2014; 67: 107–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tong J, Rathitharan G, Meyer JH, et al. Brain monoamine oxidase B and A in human Parkinsonian dopamine deficiency disorders. Brain 2017; 140: 2460–2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kiely AP, Murray CE, Foti SC, et al. Immunohistochemical and molecular investigations show alteration in the inflammatory profile of multiple system atrophy brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2018; 77: 598–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li F, Ayaki T, Maki T, et al. NLRP3 Inflammasome-related proteins are upregulated in the putamen of patients with multiple system atrophy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2018; 77: 1055–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cosenza-Nashat M, Zhao ML, Suh HS, et al. Expression of the translocator protein of 18 kDa by microglia, macrophages and astrocytes based on immunohistochemical localization in abnormal human brain. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2009; 35: 306–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guilarte TR. TSPO in diverse CNS pathologies and psychiatric disease: a critical review and a way forward. Pharmacol Ther 2019; 194: 44–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tong J, Furukawa Y, Sherwin A, et al. Heterogeneous intrastriatal pattern of proteins regulating axon growth in normal adult human brain. Neurobiol Dis 2011; 41: 458–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tong J, Meyer JH, Furukawa Y, et al. Distribution of monoamine oxidase proteins in human brain: implications for brain imaging studies. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013; 33: 863–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tong J, Wong H, Guttman M, et al. Brain alpha-synuclein accumulation in multiple system atrophy, Parkinson’s disease and progressive supranuclear palsy: a comparative investigation. Brain 2010; 133: 172–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tong J, Ang LC, Williams B, et al. Low levels of astroglial markers in Parkinson's disease: relationship to alpha-synuclein accumulation. Neurobiol Dis 2015; 82: 243–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kish SJ, Shannak K, Hornykiewicz O. Uneven pattern of dopamine loss in the striatum of patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Pathophysiologic and clinical implications. N Engl J Med 1988; 318: 876–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Geha RM, Rebrin I, Chen K, et al. Substrate and inhibitor specificities for human monoamine oxidase A and B are influenced by a single amino acid. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 9877–9882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Leenders KL, Perani D, Lammertsma AA, et al. Cerebral blood flow, blood volume and oxygen utilization. Normal values and effect of age. Brain 1990; 113: 27–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Senicourt L, Iatmanen-Harbi S, Hattab C, et al. Recombinant overexpression of mammalian TSPO Isoforms 1 and 2. Meth Mol Biol 2017; 1635: 1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Delavoie F, Li H, Hardwick M, et al. In vivo and in vitro peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor polymerization: functional significance in drug ligand and cholesterol binding. Biochemistry 2003; 42: 4506–4519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gulyas B, Makkai B, Kasa P, et al. A comparative autoradiography study in post mortem whole hemisphere human brain slices taken from Alzheimer patients and age-matched controls using two radiolabelled DAA1106 analogues with high affinity to the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor (PBR) system. Neurochem Int 2009; 54: 28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Iaccarino L, Moresco RM, Presotto L, et al. An In Vivo (11)C-(R)-PK11195 PET and in vitro pathology study of microglia activation in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Mol Neurobiol 2018; 55: 2856–2868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stokholm MG, Iranzo A, Ostergaard K, et al. Assessment of neuroinflammation in patients with idiopathic rapid-eye-movement sleep behaviour disorder: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol 2017; 16: 789–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stokholm MG, Iranzo A, Ostergaard K, et al. Extrastriatal monoaminergic dysfunction and enhanced microglial activation in idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder. Neurobiol Dis 2018; 115: 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Owen DR, Yeo AJ, Gunn RN, et al. An 18-kDa translocator protein (TSPO) polymorphism explains differences in binding affinity of the PET radioligand PBR28. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2012; 32: 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mizrahi R, Rusjan PM, Kennedy J, et al. Translocator protein (18 kDa) polymorphism (rs6971) explains in-vivo brain binding affinity of the PET radioligand [(18)F]-FEPPA. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2012; 32: 968–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Coughlin JM, Wang Y, Ma S, et al. Regional brain distribution of translocator protein using [(11)C]DPA-713 PET in individuals infected with HIV. J Neurovirol 2014; 20: 219–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Collste K, Forsberg A, Varrone A, et al. Test-retest reproducibility of [(11)C]PBR28 binding to TSPO in healthy control subjects. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imag 2016; 43: 173–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Antkiewicz-Michaluk L, Guidotti A, Krueger KE. Molecular characterization and mitochondrial density of a recognition site for peripheral-type benzodiazepine ligands. Mol Pharmacol 1988; 34: 272–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tong J, Fitzmaurice PS, Moszczynska A, et al. Do glutathione levels decline in aging human brain? Free Radic Biol Med 2016; 93: 110–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.McEnery MW, Snowman AM, Trifiletti RR, et al. Isolation of the mitochondrial benzodiazepine receptor: association with the voltage-dependent anion channel and the adenine nucleotide carrier. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992; 89: 3170–3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Joseph-Liauzun E, Farges R, Delmas P, et al. The Mr 18,000 subunit of the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor exhibits both benzodiazepine and isoquinoline carboxamide binding sites in the absence of the voltage-dependent anion channel or of the adenine nucleotide carrier. J Biol Chem 1997; 272: 28102–28106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Slobodyansky E, Guidotti A, Wambebe C, et al. Isolation and characterization of a rat brain triakontatetraneuropeptide, a posttranslational product of diazepam binding inhibitor: specific action at the Ro 5-4864 recognition site. J Neurochem 1989; 53: 1276–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lacapere JJ, Delavoie F, Li H, et al. Structural and functional study of reconstituted peripheral benzodiazepine receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2001; 284: 536–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Segonzac A, Schoemaker H, Langer SZ. Temperature dependence of drug interaction with the platelet 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter: a clue to the imipramine selectivity paradox. J Neurochem 1987; 48: 331–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Aronstam RS, Narayanan TK. Temperature effect on the detection of muscarinic receptor-G protein interactions in ligand binding assays. Biochem Pharmacol 1988; 37: 1045–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Milenkovic VM, Bader S, Sudria-Lopez D, et al. Effects of genetic variants in the TSPO gene on protein structure and stability. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0195627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Varga B, Marko K, Hadinger N, et al. Translocator protein (TSPO 18kDa) is expressed by neural stem and neuronal precursor cells. Neurosci Lett 2009; 462: 257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Batoko H, Veljanovski V, Jurkiewicz P. Enigmatic Translocator protein (TSPO) and cellular stress regulation. Trends Biochem Sci 2015; 40: 497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Veenman L, Shandalov Y, Gavish M. VDAC activation by the 18 kDa translocator protein (TSPO), implications for apoptosis. J Bioenergetics Biomembranes 2008; 40: 199–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Yamamoto T, Shibata N, Muramatsu F, et al. Oxidative stress in the human fetal brain: an immunohistochemical study. Pediatric Neurology 2002; 26: 116–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Buonocore G, Perrone S, Bracci R. Free radicals and brain damage in the newborn. Biol Neonate 2001; 79: 180–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kjaer M, Fabricius K, Sigaard RK, et al. Neocortical development in brain of young children – a stereological study. Cereb Cortex 2017; 27: 5477–5484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Primiani CT, Ryan VH, Rao JS, et al. Coordinated gene expression of neuroinflammatory and cell signaling markers in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex during human brain development and aging. PLoS One 2014; 9: e110972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Allen NJ, Lyons DA. Glia as architects of central nervous system formation and function. Science 2018; 362: 181–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kobayashi M, Jiang T, Telu S, et al. 11)C-DPA-713 has much greater specific binding to translocator protein 18 kDa (TSPO) in human brain than (11)C-(R)-PK11195. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2018; 38: 393–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Owen DR, Guo Q, Kalk NJ, et al. Determination of [(11)C]PBR28 binding potential in vivo: a first human TSPO blocking study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2014; 34: 989–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sridharan S, Raffel J, Nandoskar A, et al. Confirmation of specific binding of the 18-kDa translocator protein (TSPO) radioligand [(18)F]GE-180: a blocking study using XBD173 in multiple sclerosis normal appearing white and grey matter. Mol Imaging Biol 2019; doi: 10.1007/s11307-019-01323-8. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Plaven-Sigray P, Schain M, Zanderigo F, et al. Accuracy and reliability of [(11)C]PBR28 specific binding estimated without the use of a reference region. Neuroimage 2018; 188: 102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Frankle WG, Narendran R, Wood AT, et al. Brain translocator protein occupancy by ONO-2952 in healthy adults: a phase 1 PET study using [(11) C]PBR28. Synapse 2017; 71: e21970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rusjan PM, Wilson AA, Miler L, et al. Kinetic modeling of the monoamine oxidase B radioligand [(1)(1)C]SL25.1188 in human brain with high-resolution positron emission tomography. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2014; 34: 883–889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Salvesen L, Ullerup BH, Sunay FB, et al. Changes in total cell numbers of the basal ganglia in patients with multiple system atrophy – a stereological study. Neurobiol Dis 2015; 74: 104–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gerhard A, Banati RB, Goerres GB, et al. [11C](R)-PK11195 PET imaging of microglial activation in multiple system atrophy. Neurology 2003; 61: 686–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Venneti S, Lopresti BJ, Wiley CA. The peripheral benzodiazepine receptor (Translocator protein 18kDa) in microglia: from pathology to imaging. Progr Neurobiol 2006; 80: 308–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Liu GJ, Middleton RJ, Hatty CR, et al. The 18 kDa translocator protein, microglia and neuroinflammation. Brain Pathol 2014; 24: 631–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bradburn S, Murgatroyd C, Ray N. Neuroinflammation in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis. Age Res Rev 2019; 50: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Tu LN, Zhao AH, Hussein M, et al. Translocator protein (TSPO) affects mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation in steroidogenic cells. Endocrinology 2016; 157: 1110–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for Concentration, distribution, and influence of aging on the 18 kDa translocator protein in human brain: Implications for brain imaging studies by Junchao Tong, Belinda Williams, Pablo M. Rusjan, Romina Mizrahi, Jean-Jacques Lacapère, Tina McCluskey, Yoshiaki Furukawa, Mark Guttman, Lee-Cyn Ang, Isabelle Boileau, Jeffrey H Meyer and Stephen J Kish in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism