Abstract

Setting:

A referral hospital in Cape Town, Western Cape Province, Republic of South Africa.

Objective:

To measure the impact of a hospital-based referral service (intervention) to reduce initial loss to follow-up among children with tuberculosis (TB) and ensure the completeness of routine TB surveillance data.

Design:

A dedicated TB referral service was established in the paediatric wards at Tygerberg Hospital, Cape Town, in 2012. Allocated personnel provided TB education and counselling, TB referral support and weekly telephonic follow-up after hospital discharge. All children identified with TB were matched to electronic TB treatment registers (ETR.Net/EDRWeb). Multivariable logistic regression was used to compare reporting of culture-confirmed and drug-susceptible TB cases before (2007–2009) and during (2012) the intervention.

Results:

Successful referral with linkage to care was confirmed in 267/272 (98%) and successful reporting in 227/272 (84%) children. Children with drug-susceptible, culture-confirmed TB were significantly more likely to be reported during the intervention period than in the pre-intervention period (OR 2.52, 95%CI 1.33–4.77). The intervention effect remained consistent in multivariable analysis (adjusted OR 2.62; 95%CI 1.31–5.25) after adjusting for age, sex, human immunodeficiency virus status and the presence of TB meningitis.

Conclusions:

A simple hospital-based TB referral service can reduce initial loss to follow-up and improve recording and reporting of childhood TB in settings with decentralised TB services.

Keywords: paediatric, TB, initial loss to follow-up, reporting, notification

Abstract

Contexte :

Un grand hôpital de référence au Cap, Afrique du Sud.

Objectif :

Mesurer l’impact d’un service de référence basé en hôpital (intervention) afin de réduire les pertes de vue initiales parmi les enfants atteints de tuberculose (TB) et améliorer l’exhaustivité des données de routine de surveillance de la TB.

Schéma :

En 2012, un service de référence dédié de la TB a été créé dans le service de pédiatrie de l’hôpital Tygerberg. Le personnel dédié a fourni une éducation relative à la TB ainsi que des conseils, un soutien à la référence et un suivi téléphonique hebdomadaire après la sortie de l’hôpital. Tous les enfants identifiés comme atteints de TB ont été appariés aux registres électroniques de traitement de la TB (ETR.Net/EDRWeb). Une régression logistique multivariable a été utilisée pour comparer la notification des cas confirmés par la culture de TB pharmacorésistante avant (2007–2009) et pendant (2012) l’intervention.

Résultats :

Une référence réussie avec un lien à la prise en charge a été confirmée chez 267/272 (98%) et une notification réussie chez 227/272 (84%) enfants. Pendant la période d’intervention, les enfants atteints de TB pharmacorésistante confirmée par la culture ont été significativement plus susceptibles d’être notifiés comparés à la période précédant l’intervention (OR 2,52 ; IC95% 1,33–4,77). L’effet de l’intervention est resté stable en modèle multi variable (ORa 2,62 ; IC95% 1.31–5,25) après ajustement sur l’âge, le sexe, le statut VIH et la présence d’une méningite tuberculeuse.

Conclusion :

Un simple service de référence de la TB basé en hôpital peut réduire les pertes de vue initiales et améliorer l’enregistrement et la notification de la tuberculose de l’enfant dans un contexte de services de TB décentralisés.

Abstract

Marco de Referencia:

Un gran hospital de referencia de Ciudad del Cabo en Suráfrica.

Objetivo:

Medir el impacto de un servicio hospitalario de remisiones (intervención) destinado a disminuir la pérdida durante el seguimiento inicial de los niños con tuberculosis (TB) y mejorar la exhaustividad de los datos de la vigilancia sistemática de la TB.

Método:

En el 2012, se instauró un servicio dedicado a la derivación de los casos de TB en las unidades pediátricas del Hospital Tygerberg. Miembros designados del personal impartían educación y asesoramiento, apoyo a la derivación de los casos de TB y seguimiento telefónico semanal después del alta hospitalaria. Se emparejaron todos los niños detectados con TB con los casos de los registros electrónicos de tratamiento antituberculoso (ETR.Net/EDRWeb). Con un modelo de regresión logística multivariante se comparó la notificación de los casos de casos de TB normosensible confirmada por cultivo antes de la intervención (2007–2009) y durante la misma (2012).

Resultados:

Se confirmó la remisión eficaz con vinculación a los servicios de atención en 267 de 272 niños (98%) y la notificación de 227 de los 272 (84%). La notificación de los niños con TB normosensible confirmada por cultivo fue mucho más probable durante el período de la intervención que antes de la misma (OR 2,52; IC95% 1,33–4,77). El efecto de la intervención permaneció constante en el modelo multivariante (aOR 2,62; IC95% 1,31–5,25) tras ajustar con respecto a la edad, el sexo, la situación frente al virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana y la presencia de meningitis tuberculosa.

Conclusión:

Un servicio hospitalario sencillo de remisiones disminuye las pérdidas iniciales durante el seguimiento y mejora el registro y la notificación de los casos de TB en los niños de un entorno con servicios de TB descentralizados.

Inaccurate surveillance data for childhood tuberculosis (TB; age <15 years) has been noted as a critical concern globally, and one which limits our ability to appropriately manage paediatric TB.1,2 Since 2013, the World Health Organization (WHO) has been urging countries to prioritise improving the quality of TB surveillance data in children;3 however, only 45% of the estimated 1 million childhood TB cases worldwide were reported to the WHO in 2017.4,5 Under-detection of cases and incomplete reporting of detected cases both contribute to this large deficit.1

In 2017, South Africa reported only 40% of the 39 000 estimated child TB caseload.4 South Africa follows a decentralised model of TB care, and the primary sources of TB surveillance data are two electronic TB treatment registers: ETR.Net for drug-susceptible (DS)-TB and EDRWeb for drug-resistant (DR)-TB. Both registers are used for TB case notification at local, national and international levels.6,7

Naidoo et al. estimated that 12% of the total TB burden in South Africa in 2013 was lost between diagnosis and treatment initiation (initial loss to follow-up [ILTFU]).8 Substantial ILTFU (52% and 58%) has been documented among hospital-diagnosed TB patients in South Africa.9,10 As TB surveillance data are typically captured at treatment initiation, ILTFU contributes to the reporting gap in South Africa. Successful linkage of TB care between hospital and community-based PHC facilities is another recognised challenge.11 Following TB treatment initiation in South African hospitals, unsuccessful linkage to PHC care occurred in respectively 12% (Western Cape, 2008/2009),9 21% (Gauteng, 2001),12 23% (Gauteng, 2009)13 and 31% (Kwa-Zulu Natal, 2005)10 of TB patients, with children (age <15 years ) being at even higher risk than adults for discontinuing TB care.9 In provinces in South Africa where general hospitals are not required to report TB case-notification data, such as the Western Cape, TB patients who started treatment in-hospital but are not successfully linked to care, contributes to the reporting gap.

Childhood TB, especially TB in young children, is often diagnosed at hospital level due to challenges faced in specimen collection and diagnosis.14,15 A retrospective audit of children diagnosed with culture-confirmed TB during 2007–2009 at a large tertiary hospital in Cape Town, Western Cape Province, South Africa, found an overall reporting gap of 38% (101/267); 32% (58/183) among children discharged home to continue TB care.16 Given the large number of children with TB managed at this hospital (approximately 400 per year)14 and other referral centres, this underestimation of the burden and spectrum of TB disease can have a considerable impact on resource allocation and service delivery. An evaluation of community-based TB surveillance data in one health sub-district in Cape Town found frequent omission of severe cases and a reporting gap of 15% (54/354) among children, all of whom had been diagnosed at the referral hospital.17

Similar challenges with hospital notification of childhood TB cases have been reported in other settings. A study from Indonesia found a large reporting gap in children, with only 75/4821 (1.6%) child TB cases managed in hospitals being recorded and reported to the National TB Programme.18 At a private, tertiary hospital in India during 2015/2016, only 24/264 (9.1%) of child TB cases were notified.19 In Cotonou, Benin, the hospital contributed 29 (16%) of the total child TB burden, of which none had been reported.20 Although data on the gap in hospital reporting for childhood TB are available, there is a paucity of data on interventions to address this.

Continuation of TB care from hospital to community-based PHC facilities and accurate reporting is essential to reduce ILTFU and accurately capture the true burden and spectrum of TB in children. Dedicated TB referral support interventions in hospitals has been previously shown to improve hospital-community linkage to care and TB reporting in Gauteng, South Africa.21,22 We implemented a hospital-based intervention to support referral and linkage of children with TB from the hospital to community-based PHC facilities and evaluated the impact of this intervention on the completeness of routine TB reporting data.

METHODS

Study design and population

Prospective hospital surveillance activities identified 395 children (age 0–<13 years) routinely managed with either confirmed or clinically diagnosed TB at Tygerberg Hospital (TBH) during 2012.14 Surveillance methods, clinical characteristics, care pathways and treatment outcomes have been previously reported.14 Prospective enhanced surveillance provided the foundation for an intervention to support linkage to care focussed on children with TB who were discharged home to continue routine TB care at either community-based PHC facilities or as an outpatient at TBH.

All eligible children during the intervention period (January–December 2012) contributed to a prospective cohort. To assess the intervention impact on the completeness of reported data, a before-and-after study design was used to compare prospective cohort data from the intervention period with data from a previous retrospective cohort study of children with culture-confirmed TB at the same hospital (July 2007–June 2009).16

Setting

South Africa remains one of the highest TB burden countries globally, with an estimated annual TB incidence rate of more than 500 per 100 000 population per year since 2000.4 Of the 296 996 new TB case notifications that were reported in 2012 to the WHO, 38 578 (13%) were children aged <15 years.23 TBH is one of two tertiary referral hospitals in Cape Town, serving the paediatric population in the Western Cape Province. During 2012, the hospital had 268 paediatric beds and a staff complement of more than 100 clinical personnel.24 It serves as a referral hospital for both uncomplicated and complicated TB cases from surrounding high-burden communities, and for complicated TB cases across the province. The majority of the paediatric TB cases are discharged home to continue TB care, and others are referred to TB hospitals, secondary-level hospitals or chronic, medium-term care facilities.14,16 Following a diagnosis of TB meningitis (TBM), eligible children can enter a home-based care programme with monthly outpatient follow-up at TBH until treatment completion.25

An electronic register for DR-TB (EDRWeb) was piloted and implemented in South Africa from 2009. In addition to the changes in surveillance and reporting, paediatric DR-TB care was decentralised in 2011 at provincial level. Xpert MTB/RIF (Cepheid, Sunnydale, CA) was only routinely implemented for paediatric TB after 2012.

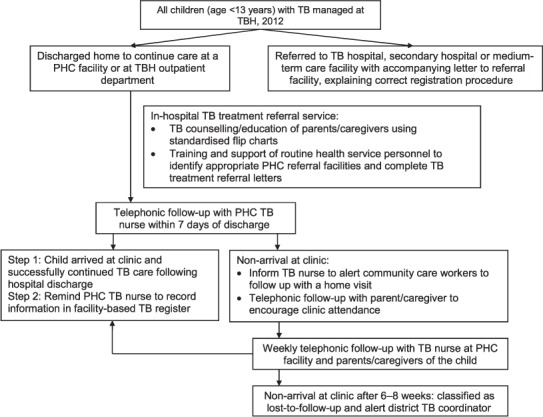

Linkage to care intervention

A hospital-based TB referral service, staffed by a dedicated full-time nursing officer and a lay healthcare worker, was established in the paediatric wards and outpatient clinics at TBH in 2012. The Figure provides an overview of the intervention. In-hospital support for children routinely diagnosed with TB by TBH clinical staff included TB education and counselling of parents/caregivers (by telephone if not possible in person), and supporting completion of routine TB referral stationary. During study implementation, paediatric hospital personnel received ongoing training and feedback regarding appropriate TB referral procedures. All intervention activities were implemented as part of an integrated package of TB care for children at TBH. Following discharge, intervention support included weekly follow-up by telephone with TB staff at the receiving PHC to confirm whether the child had accessed care, and with parents/caregivers if necessary. TB nurses at the PHCs were reminded to record all children into the PHC-based paper TB register. Parents/caregivers of children who were followed up monthly at the TBH outpatient department were asked to attend their community-based PHC facility upon hospital discharge and at the end of treatment to ensure recording of the child and their TB treatment outcome in the PHC-based TB treatment registers.

FIGURE.

Hospital intervention to support successful referral and reporting of childhood TB, Tygerberg Hospital, Cape Town, Western Cape Province, Republic of South Africa, January–December 2012. TB = tuberculosis; TBH = Tygerberg Hospital; PHC = primary health care.

Data collection, definitions and outcome measures

Demographic and clinical information were extracted from routine patient records. Based on standard of care diagnostic testing in this setting (chest radiography and at least two respiratory specimens), the duration of admission was divided into two categories—1–3 days or ⩾4 days—to distinguish between uncomplicated and more complicated admissions. Referral information was captured through telephonic follow-up with healthcare providers and parents/caregivers, as well as patient record reviews. A successful referral outcome required telephonic (with a healthcare provider) or paper-based confirmation of attendance at a community-based PHC facility or outpatient clinic following hospital discharge.

Standard case report forms were completed and dual-captured in an access-controlled database with restricted access. Probabilistic record linkage was used to match identified TBH patients to an extracted TB surveillance database (ETR.Net and EDRWeb; 2011–2013).26 Following electronic linkage, demographic and TB episode data were manually reviewed for accuracy. Previously described methods and criteria were used to determine successful matching, consistent with methods used in the baseline/pre-intervention assessment.16 Data were de-identified upon completion of matching procedures.

Statistical analysis

Results are reported as numbers and percentages for categorical variables, and median and inter-quartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables. Statistical comparisons were made to assess differences between children who had successfully received the intervention vs. those who did not, and to evaluate associations between primary outcome measures and in-hospital intervention activities, relevant admission and referral factors. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported. The χ2 test or Fisher’s Exact test was used for hypothesis testing.

To measure the impact of the intervention on TB case notification, data from the intervention period (2012) were compared with data from the pre-intervention period (baseline; 2007–2009) at the same hospital using an intention-to-treat analysis approach. Baseline data were limited to children with culture-confirmed TB. Therefore, analysis of the intervention period included only children with culture-confirmed TB, although analysis with the total intervention group was also performed. Demographic, admission and clinical factors were compared to assess comparability between the groups from the two periods. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression were used to measure the impact of the intervention on reporting, and to identify and adjust for possible confounders. Data are reported as ORs and adjusted odds ratios (aORs). Due to the changes in reporting for children with DR-TB over the total study period, primary analysis included only children treated for DS-TB during both periods. The multivariable model included age, sex and HIV status a priori, and variables that were significantly associated with outcomes, at P < 0.05, in uni-variable analyses. Analyses were completed using Stata SE version 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethics approval was obtained from the Stellenbosch University Health Research Ethics Committee, Tygerberg, South Africa (N11/09/287), and provincial (RP143/2011) and municipal authorities (ID 10266)). A waiver of individual informed consent was granted since the intervention was implemented as part of standard paediatric clinical care.

RESULTS

During 2012, 272 children with TB (102 [38%] culture-confirmed) were discharged to continue TB care at a community-based PHC facility (n = 244) or at the TBH outpatient department (n = 28). TB education and counselling were completed with parents/caregivers of 230 (85%) children, and referral documentation was completed for 220 (81%) children. Table 1 gives the associations between demographic, clinical, care pathway and admission factors and the completion of in-hospital intervention activities. Bacteriological confirmation, diagnosis after discharge and hospital admission ⩽3 days were associated with not completing TB education. Extrapulmonary TB (EPTB) only, bacteriological confirmation and a pre-admission or post-discharge TB diagnosis were associated with incomplete TB referral documentation.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of children with TB discharged from Tygerberg Hospital, Cape Town, Western Cape Province, Republic of South Africa, by completion status of in-hospital linkage-to-care intervention activities, January–December 2012 (n = 272)

| TB education | Referral documentation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completed (n = 230, 84.6%) n/N (%) | P value | Completed (n = 220, 80.8%) n/N (%) | P value | |

| Demographic/clinical factors | ||||

| Age, years | ||||

| 0–<2 | 103/119 (86.6) | 97/119 (81.5) | ||

| 2–<5 | 74/85 (87.1) | 73/85 (85.9) | ||

| 5–13 | 53/68 (77.9) | 0.218 | 50/68 (73.5) | 0.151 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 130/155 (83.9) | 131/155 (84.5) | ||

| Female | 100/117 (85.5) | 0.718 | 89/117 (76.1) | 0.079 |

| HIV status | ||||

| Positive | 51/59 (86.4) | 48/59 (81.4) | ||

| Negative | 166/195 (85.1) | 161/195 (82.6) | ||

| Unknown | 13/18 (72.2) | 0.316 | 11/18 (61.1) | 0.086 |

| TB disease type | ||||

| PTB only | 130/154 (84.4) | 132/154 (85.7) | ||

| Both PTB and EPTB | 62/72 (86.1) | 62/72 (86.1) | ||

| EPTB only | 38/46 (82.6) | 0.874 | 26/46 (56.5) | 0.001 |

| Diagnostic status | ||||

| Culture-confirmed M. tuberculosis | 80/102 (78.4) | 76/102 (74.5) | ||

| Clinical diagnosis | 150/170 (88.2) | 0.030 | 144/170 (84.7) | 0.038 |

| TB treatment regimen | ||||

| DS-TB regimen | 216/258 (83.7) | 209/258 (81.0) | ||

| DR-TB regimen* | 14/14 (100) | 0.137† | 11/14 (78.6) | 0.735† |

| TB care pathway/admission factors | ||||

| TB diagnostic pathway | ||||

| Diagnosed before admission | 50/56 (89.3) | 36/56 (64.3) | ||

| Diagnosed during admission | 174/203 (85.7) | 178/203 (87.7) | ||

| Diagnosed after discharge‡ | 6/13 (46.2) | <0.001 | 6/13 (46.2) | <0.001 |

| Level of health care accessed before diagnosis§ | ||||

| Primary health care | 11/13 (84.6) | 9/13 (69.2) | ||

| Other hospital | 39/43 (90.7) | 0.615† | 27/43 (62.8) | 0.752† |

| Duration of hospital visit/admission | ||||

| Outpatients | 28/34 (82,4) | 28/34 (82.4) | ||

| 1–⩽3 days | 23/39 (59.0) | 30/39 (76.9) | ||

| ⩾4 days | 179/199 (90.0) | <0.001 | 162/199 (81.4) | 0.787 |

*Includes all types of drug resistance.

† Fisher’s Exact test used if χ2 assumptions were not met.

‡ 12 of 13 children who were diagnosed only after discharge were diagnosed based on a culture-positive result that became available only after discharge.

§ Including only children diagnosed before hospital admission.

TB = tuberculosis; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; PTB = pulmonary TB; EPTB = extrapulmonary TB; DS-TB = drug-susceptible TB; DR-TB = drug-resistant TB.

Referral and reporting outcomes are shown in Table 2 in relation to the in-hospital intervention activities, clinical and TB care pathway factors. Of the 272 children, successful referral was confirmed in 267 (98%), and successful reporting in 227 (84% matched with the routine TB surveillance data [ETR.Net/EDRWeb]). Receiving education/counselling was associated with successful referral. Children who were followed as hospital outpatients, including all children with TBM, as well as children with DR-TB, were less likely to be reported.

TABLE 2.

Referral and reporting outcomes of a hospital-community linkage to care intervention for children with TB discharged from Tygerberg Hospital, Cape Town, Western Cape Province, Republic of South Africa, January–December 2012 (n = 272)

| Overall (n = 272) n (%) | Referral outcomes | Reporting outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accessed clinical care (n = 267, 98.2%) n (%) | P value | Recorded in ETR.Net/EDRWeb (n = 227, 83.5%) n (%) | P value | ||

| In-hospital intervention activities | |||||

| TB education/counselling | |||||

| Completed* | 230 (84.6) | 229 (99.6) | 188 (81.7) | ||

| Not possible† | 42 (15.4) | 38 (90.5) | 0.002‡ | 39 (92.9) | 0.075 |

| Relationship with counselled caregiver | |||||

| Parent | 214/228 (93.9) | 213/214 (99.5) | 176/214 (82.2) | ||

| Other | 14/228 (6.1) | 14/14 (100) | 1.000‡ | 10/14 (71.4) | 0.297‡ |

| Appropriate referral documents | |||||

| Completed | 220 (80.9) | 217 (98.6) | 187 (85.0) | ||

| Not completed | 52 (19.1) | 50 (96.2) | 0.244‡ | 40 (76.9) | 0.162 |

| Demographic/clinical factors | |||||

| Age, years | |||||

| 0–<2 | 119 (43.7) | 115 (96.6) | 95 (79.8) | ||

| 2–<5 | 85 (31.3) | 85 (98.8) | 70 (82.4) | ||

| 5–13 | 68 (25.0) | 68 (25.5) | 0.324‡ | 62 (91.2) | 0.126 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 155 (57.0) | 153 (98.7) | 127 (81.9) | ||

| Female | 117 (43.0) | 114 (97.4) | 0.655‡ | 100 (85.5) | 0.437 |

| HIV status | |||||

| Positive | 59 (21.7) | 58 (98.3) | 49 (83.1) | ||

| Negative | 195 (71.7) | 191 (98.0) | 164 (84.1) | ||

| Unknown | 18 (6.6) | 18 (100) | 1.000‡ | 14 (77.8) | 0.784 |

| TB disease type | |||||

| PTB only | 154 (56.6) | 150 (97.4) | 128 (83.1) | ||

| Both PTB and EPTB | 72 (26.5) | 71 (98.6) | 62 (86.1) | ||

| EPTB only | 46 (16.9) | 46 (100) | 0.835‡ | 37 (80.4) | 0.710 |

| Disseminated TB | |||||

| TBM | 26 (9.6) | 26 (100) | 1.000‡ | 16 (61.5) | 0.004‡ |

| Miliary TB | 10 (3.7) | 10 (100) | 1.000‡ | 8 (80.0) | 0.673‡ |

| Diagnostic status | |||||

| Culture-confirmed M. tuberculosis | 102 (37.5) | 100 (98.0) | 86 (84.3) | ||

| Clinical diagnosis | 170 (62.5) | 167 (98.2) | 1.000‡ | 141 (82.9) | 0.768 |

| TB treatment regimen | |||||

| DS-TB treatment | 258 (94.9) | 253 (98.1) | 219 (84.9) | ||

| Any DR-TB treatment | 14 (5.2) | 14 (100) | 1.000‡ | 8 (57.1) | 0.016‡ |

| TB care pathway/admission factors | |||||

| TB diagnostic pathway | |||||

| Diagnosed before admission | 56 (20.6) | 55 (98.2) | 43 (76.8) | ||

| Diagnosed during admission | 203 (74.6) | 199 (98.0) | 172 (84.7) | ||

| Diagnosed after discharge§ | 13 (4.8) | 13 (100) | 1.000‡ | 12 (92.3) | 0.249 |

| Duration of hospital visit/admission | |||||

| Outpatients | 34 (12.5) | 34 (100) | 31 (91.2) | ||

| 1–⩽3 days | 39 (14.3) | 37 (94.9) | 35 (89.7) | ||

| ⩾4 days | 199 (73.2) | 196 (98.5) | 0.263‡ | 161 (80.9) | 0.172 |

| Location of monthly follow-up | |||||

| Community-based | 244 (89.7) | 239 (98.0) | 209 (85.7) | ||

| Hospital-based¶ | 28 (10.3) | 28 (100) | 1.000‡ | 18 (64.3) | 0.012‡ |

* 228 of the 230 education sessions were completed with the child’s primary caregiver.

† Parent or caregiver not available or contactable for TB-specific education.

‡ Fisher’s Exact were used if χ2 assumptions not met.

§ 12 of 13 children who were diagnosed only after discharge were diagnosed based on culture-positive result that became available only after discharge.

¶ 26/28 (92.9%) children who were followed up monthly at Tygerberg Hospital, Cape Town, Western Cape Province, Republic of South Africa, had TBM and were part of the established TBM home-based care programme.

TB = tuberculosis; ETR.Net = electronic TB register for drug-susceptible TB; EDRWeb = electronic TB register for drug-resistant TB; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; PTB = pulmonary TB; EPTB = extrapulmonary TB; DS-TB = drug-susceptible TB; DR-TB = drug-resistant TB; TBM = TB meningitis.

Table 3 compares demographic, admission and clinical characteristics of children with culture-confirmed TB who were discharged to continue TB care by time period: baseline (2007–2009; n = 18316) and intervention (2012; n = 102). Children from the two periods were similar regarding age distribution, sex, patient category, duration of admission, TB disease spectrum, TBM, miliary TB and drug resistance. The proportion of children with unknown HIV status decreased substantially over time from 59 (32%) to 11 (11%), and documented HIV infection decreased from 29 (16%) to 12 (12%).

TABLE 3.

Characteristics of children with culture-confirmed TB discharged from Tygerberg Hospital, Cape Town, Western Cape Province, Republic of South Africa, during baseline and intervention periods (n = 285)

| Baseline 2007–2009 (n = 183) n (%) | Intervention 2012 (n = 102) n (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and admission factors | |||

| Age, years | |||

| 0–<2 | 89 (48.6) | 39 (38.2) | |

| 2–<5 | 49 (26.8) | 30 (29.4) | |

| 5–13 | 45 (24.6) | 33 (32.4) | 0.204 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 105 (57.4) | 54 (52.9) | |

| Female | 78 (42.6) | 48 (47.1) | 0.470 |

| Patient category* | |||

| Outpatients only | 52/177 (29.4) | 20 (19.6) | |

| Overnight admission | 125/177 (70.6) | 82 (80.4) | 0.072 |

| Duration of hospital admission* | |||

| 1–⩽3 days | 35/125 (28.0) | 14/82 (17.1) | |

| ⩾4 days | 90/125 (72.0) | 68/82 (82.9) | 0.070 |

| Clinical factors | |||

| HIV status | |||

| Negative | 95 (51.9) | 79 (77.5) | |

| Positive | 29 (15.9) | 12 (11.8) | |

| Unknown | 59 (32.2) | 11 (10.8) | <0.001 |

| TB disease type | |||

| PTB only | 86 (47.0) | 43 (42.2) | |

| Both PTB and EPTB | 58 (31.7) | 40 (39.2) | |

| EPTB only | 39 (21.3) | 19 (18.6) | 0.439 |

| Disseminated TB | |||

| TBM | 15 (8.2) | 8 (7.8) | 0.916 |

| Miliary TB† | 8 (4.4) | 5 (4.9) | 1.000‡ |

| Drug resistance (binary variable) | 12 (6.6) | 5 (4.9) | |

| INH monoresistance | 5 (2.7) | 3 (2.9) | |

| RMP monoresistance | 2 (1.1) | 1 (1.0) | |

| MDR-/XDR-TB | 5 (2.7) | 1 (1.0) | 0.572 |

* Unknown for 6/183 (3%) children from the baseline period.

† Total number of patients with miliary TB who also had TBM: 2 and 2, respectively.

‡ Fisher’s Exact were used if χ2 assumptions not met.

TB = tuberculosis; PTB = pulmonary TB; EPTB = extra-pulmonary TB; TBM = TB meningitis; INH = isoniazid; RMP = rifampicin; MDR = multidrug-resistant TB; XDR-TB = extensively drug-resistant.

Table 4 provides results of the univariable and multivariable analyses to assess the impact of the intervention on reporting of children with DS-TB. During the intervention period, children discharged home to continue TB care were 2.52 times (95%CI 1.33–4.77, P= 0.004) more likely to be recorded in the ETR.Net than during the baseline period. The intervention effect remained consistent in the multivariable model, adjusting for age, sex, HIV status and TBM (aOR 2.62, 95%CI 1.31–5.25; P = 0.006). In the multivariate model adjusting for the effect of the intervention, the odds of children with TBM being reported remained significantly lower than children without TBM (aOR 0.18, 95%CI 0.07–0.48; P = 0.001). Although data are not presented, multivariable analyses of the culture-confirmed baseline group and the total intervention group (culture-confirmed plus clinically diagnosed cases) adjusted for the same variables, yielded very similar results (n = 429: aOR 2.62, 95%CI 1.57–4.38, P < 0.001).

TABLE 4.

Impact of a hospital-community linkage to care intervention on completeness of TB reporting in children discharged with culture-confirmed, drug-susceptible TB during baseline and intervention, Tygerberg Hospital, Cape Town, Western Cape Province, Republic of South Africa (n = 268)

| Completeness of reporting | Univariable analyses | Multivariable analyses | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reported in ETR.Net (n = 199) n (%) | Not reported in ETR.Net (n = 69) n (%) | OR (95%CI) | P value | aOR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Impact of intervention | ||||||

| Baseline period (2007–2009) | 117 (58.8) | 54 (78.3) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Intervention period (2012) | 82 (41.2) | 15 (21.7) | 2.52 (1.33–4.77) | 0.004 | 2.62 (1.31–5.25) | 0.006 |

| Covariates | ||||||

| Age, years | ||||||

| 0–<2 | 90 (45.2) | 33 (47.8) | Reference | |||

| 2–<5 | 49 (24.6) | 22 (31.9) | 0.82 (0.43–1.55) | 0.536 | 0.83 (0.42–1.66) | 0.604 |

| 5–13 | 60 (30.2) | 14 (20.3) | 1.57 (0.78–3.18) | 0.209 | 1.51 (0.71–3.22) | 0.283 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 116 (58.3) | 37 (53.6) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Female | 83 (41.7) | 32 (46.4) | 0.83 (0.48–1.43) | 0.500 | 0.85 (0.47–1.52) | 0.579 |

| Patient category and admission duration* | ||||||

| Outpatients | 52/196 (26.5) | 16/67 (23.9) | Reference | |||

| 1–⩽3 days | 35/196 (17.9) | 11/67 (16.4) | 0.98 (0.41–2.36) | 0.962 | ||

| ⩾4 days | 109/196 (55.6) | 40/67 (59.7) | 0.84 (0.43–1.63) | 0.605 | — | |

| HIV status | ||||||

| Negative | 122 (61.3) | 39 (56.5) | Reference | Reference | ||

| Positive | 30 (15.1) | 9 (13.1) | 1.07 (0.47–2.44) | 0.880 | 1.01 (0.42–2.44) | 0.974 |

| Unknown | 47 (23.6) | 21 (30.4) | 0.72 (0.38–1.34) | 0.296 | 0.81 (0.40–1.61) | 0.540 |

| TB disease type | ||||||

| PTB only | 88 (44.2) | 34 (49.3) | Reference | |||

| Both PTB and EPTB | 76 (38.2) | 18 (26.1) | 1.63 (0.85–3.12) | 0.139 | ||

| EPTB only | 35 (17.6) | 17 (24.6) | 0.80 (0.39–1.60) | 0.523 | — | |

| Disseminated TB | ||||||

| TBM | 8 (4.0) | 12 (17.4) | 0.20 (0.08–0.51) | 0.001 | 0.18 (0.07–0.48) | 0.001 |

| Miliary TB† | 10 (5.0) | 2 (2.9) | 1.78 (0.38–8.30) | 0.737‡ | — | |

* Duration of admission unknown for 5 children from the baseline period.

† 1/10 and 2/2 children with miliary TB also had TBM.

‡ Fisher’s Exact were used if χ2 assumptions not met.

TB = tuberculosis; ETR.NET = electronic tb register for drug-susceptible TB; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; AOR = adjusted OR; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; TBM = TB meningitis; PTB = pulmonary TB; EPTB = extrapulmonary TB.

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that a simple linkage to care intervention can substantially reduce the hospital reporting gap for childhood TB. Children discharged home to continue TB care were nearly three times more likely to be reported and included in routine surveillance during the intervention period compared to the baseline period, after adjusting for age, sex, HIV status and TBM. In addition to the impact on reporting, the intervention allowed for confirmation of the continuity of clinical care for nearly all children (98.2%), resulting in <2% ILTFU.

Two referral hospitals in Gauteng Province have successfully implemented interventions to address challenges in linkage to care. A dedicated TB care and linkage service at a large tertiary referral hospital in Johannesburg, South Africa, reduced losses between hospital and PHC referrals for adults and children from 21% (2001) to 6% (2003–2005) and improved reporting of TB patients.21 Age-stratified results were unfortunately not reported. Implementation of a TB Focal Point at another tertiary hospital decreased the proportion of TB cases failing to link to TB care from 23% in 2009 to 14% during 2012.22 Our study showed similar improvement when dedicated staff were recruited to support TB patients with both the referral and reporting processes. However, interventions involving clinical personnel are costly and not always sustainable in resource-limited settings. At a district-level hospital, comparable results were achieved by only one dedicated lay health care worker for referral support and follow-up, provided surveillance was done by routine clinical personnel; 93 (96%) of child TB cases successfully accessed PHC care and 89 (90%) were matched in the ETR.Net/EDRWeb.15

In settings where information technology infrastructure is available, automated, electronic processes at hospital discharge could greatly assist with surveillance and linking of important referral processes, but will still rely on personnel at the referral hospital to provide sufficient information and the receiving facility to act on the information. Another potential solution to close this reporting gap would be to mandate all hospitals to report TB data.

The logistics around surveillance and supporting paediatric TB patients and their families in a large referral hospital with multiple wards and a large staff complement is complex. Despite dedicated efforts and multiple attempts, TB counselling was not possible for 15% of patients and referral documentation was not completed for 19%. Furthermore, children managed at referral hospitals often have complex admission and care pathways and move between different levels of care.14 It is therefore not surprising that children who were diagnosed only after hospital discharge, either due to non-resolving symptoms or a positive culture at follow-up, were less likely to receive counselling and correct referral documentation. Similarly, counselling was less frequently performed if the duration of the hospital visit was short (⩽3 days), possibly due to the fact that patients were discharged before the study team could counsel the parent/caregiver or obtain reliable contact information. Irrespective of these challenges, we used an intention-to-treat analysis approach and the observed intervention effect is therefore a conservative estimate.

During the intervention period, approximately 10% (28/272) of the children who were discharged home were followed monthly as outpatients at the referral hospital. The majority had TBM (n = 26) and were treated as part of a dedicated TBM home-based care programme at TBH. As TBH was not required to report TB data, we encouraged the caregivers of these children to attend their community-based PHC facility at the beginning and end of treatment to facilitate appropriate recording in the TB register and allow for reporting. These extra visits place an additional burden on the families, and staff at the PHC facilities are often reluctant to include patients in their reporting data if they are not primarily responsible for the patients’ TB treatment. Therefore, it was not unexpected that children who were followed up at the hospital during the intervention were significantly less likely to be reported than those who were followed up at their community-based PHC facility (P = 0.012). The highly significant association between TBM and incomplete reporting observed in univariable analysis became even more pronounced in multivariable analysis (aOR 0.18, 95%CI 0.07–0.48), and is likely a reflection of the difference in place of attendance for monthly follow-up for children with TBM.

To our knowledge, this was the first study to specifically evaluate the impact of a hospital-based linkage-to-care intervention on childhood TB case notification. Our intervention focussed on children continuing TB care from home, and although this included almost two thirds of children diagnosed with TB, completeness of reporting of children discharged to TB hospitals, other general hospitals or medium-term care facilities, were not addressed. These children likely represent more severe cases of disease or social problems, and their reporting is critical to ensure accurate reflection of the full spectrum of TB disease in children. Completeness of reporting of in-hospital deaths is an important factor not addressed in our study, but one that needs to be considered in future interventions to improve TB mortality data. Another limitation was that our baseline data were limited to culture-confirmed children only. Therefore, we could only evaluate the impact of the intervention on children with culture-confirmed disease, although analyses of the total intervention group showed similar results. The only difference between the baseline and intervention groups was a decrease in unknown HIV status during the intervention period. HIV testing has improved substantially in the entire country, and an increase in the number of children with a known HIV status was therefore expected in the intervention period. HIV status was not associated with completeness of reporting in univariable analysis, but were included a priori in the multivariable model. Due to the changes in DR-TB care and surveillance between the baseline and intervention periods, we could not accurately evaluate the impact of our intervention on the small number of children with DR-TB (n = 26).

CONCLUSIONS

Adequately supporting linkage-to-care of children with TB between hospitals and community-based PHC facilities can minimise ILTFU and substantially improve hospital reporting of childhood TB. Mandating all hospitals to function as TB reporting units can comprehensively address and reduce the hospital reporting gap for childhood TB in South Africa. Future research should evaluate scale-up and cost-effectiveness of different approaches to improve TB reporting from hospitals and strengthen linkage and referrals of children with TB.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge D Leukes, E Viljoen, L du Plessis and R Solomons for their contribution to study activities and data collection. This operational research was funded by the Fogarty International Centre (Bethesda, MD, USA) Grant (3U2RTW007370-05S1). The funding body did not have any role in study design, data collection, analysis, data interpretation or in writing the manuscript. KDP is supported by a South African National Research Foundation (NRF) South African Research Chairs Initiative (SARCHI) grant to ACH. HSS received a NRF grant. The financial assistance of the NRF towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed, and conclusions arrived at, are those of the authors and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Seddon J A, Jenkins H E, Liu L et al. Counting children with tuberculosis: why numbers matter. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19(12 Suppl 1):9–16. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marais B J. Quantifying the tuberculosis disease burden in children. Lancet. 2014;383(9928):1530–1531. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60489-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organisation Roadmap for childhood tuberculosis. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2013. http://www.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/89506/1/9789241506137_eng.pdf Accessed February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organisation Global tuberculosis report, 2018. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2018. WHO/CDS/TB/2018.20. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organisation Roadmap towards ending TB in children and adolescents. Geneva: 2018. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/275422/9789241514798-eng.pdf?ua=1 Accessed 16 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Department of Health South Africa National Tuberculosis management guidelines, 2008. Pretoria, Republic of South Africa: DoH; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Department of Health South Africa National tuberculosis guidelines, 2014. Pretoria, Republic of South Africa: DoH; 2014. https://sahivsoc.org/Files/NTCP_Adult_TB%20Guidelines%2027.5.2014.pdf=1 Accessed February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naidoo P, Theron G, Rangaka M X et al. The South African tuberculosis care cascade: estimated losses and methodological challenges. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(Suppl 7):S702–S713. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dudley L, Mukinda F, Dyers R, Marais F, Sissolak D. Mind the gap! Risk factors for poor continuity of care of TB patients discharged from a hospital in the Western Cape, South Africa. PLoS One. 2018;13(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190258. e0190258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loveday M, Thomson L, Chopra M, Ndlela Z. A health systems assessment of the KwaZulu-Natal tuberculosis programme in the context of increasing drug resistance. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12(9):1042–1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hinderaker S G, Fatima R. Lost in time and space: the outcome of patients transferred out from large hospitals. Public Health Action. 2013;3(1):2. doi: 10.5588/pha.13.0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edginton M E, Wong M L, Phofa R, Mahlaba D, Hodkinson H J. Tuberculosis at Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital: numbers of patients diagnosed and outcomes of referrals to district clinics. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9(4):398–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voss De Lima Y, Evans D, Page-Shipp L et al. Linkage to care and treatment for TB and HIV among people newly diagnosed with TB or HIV-associated TB at a large, inner city South African hospital. PLoS One. 2013;8(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049140. e49140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.du Preez K, Schaaf H S, Dunbar R et al. Complementary surveillance strategies are needed to better characterise the epidemiology, care pathways and treatment outcomes of tuberculosis in children. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):397. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5252-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.du Preez K, du Plessis L, O’Connell N, Hesseling A C. Burden, spectrum and outcomes of children with tuberculosis diagnosed at a district-level hospital in South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2018;22(9):1037–1043. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.17.0893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.du Preez K, Schaaf HS, Dunbar R et al. Incomplete registration and reporting of culture-confirmed childhood tuberculosis diagnosed in hospital. Public Health Action. 2011;1(1):19–24. doi: 10.5588/pha.11.0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marais B J, Hesseling A C, Gie R P, Schaaf H S, Beyers N. The burden of childhood tuberculosis and the accuracy of community-based surveillance data. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10(3):259–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lestari T, Probandari A, Hurtig A K, Utarini A. High caseload of childhood tuberculosis in hospitals on Java Island, Indonesia: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2011 Jan;11:784. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siddaiah A, Ahmed M N, Kumar A M V et al. Tuberculosis notification in a private tertiary care teaching hospital in South India: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(2) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023910. e023910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ade S, Harries A D, Trébucq A et al. The burden and outcomes of childhood tuberculosis in Cotonou, Benin. Public Health Action. 2013;3(1):15–19. doi: 10.5588/pha.12.0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edginton M E, Wong M L, Hodkinson H J. Tuberculosis at Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital: an intervention to improve patient referrals to district clinics. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10(9):1018–1022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jong E, Sanne I M, van Rie A, Menezes C N. A hospital-based tuberculosis focal point to improve tuberculosis care provision in a very high burden setting. Public Health Action. 2013;3(1):51–55. doi: 10.5588/pha.12.0073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organisation Global tuberculosis report, 2013. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2013. WHO/HTM/TB/2013.11. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Western Cape Government Tygerberg Hospital Annual report, 2012. Cape Town, Republic of South Africa: Western Cape Government; 2014. https://www.westerncape.gov.za/your_gov/153/documents/annual_reports/2012eng.pdf?sequence=1 Accessed February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schoeman J, Malan G, van Toorn R, Springer P, Parker F, Booysen J. Home-based treatment of childhood neurotuberculosis. J Trop Pediatr. 2009;55(3):149–154. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmn097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sayers A, Ben-Shlomo Y, Blom A W, Steele F. Probabilistic record linkage. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(3):954–964. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]