Abstract

This study reports the first phytochemical and biological characterization in treatment of adrenocortical carcinoma cells (H295R) of extracts from Nidularium procerum, an endemic bromeliad of Atlantic Forest vulnerable to extinction. Extracts of dry leaves obtained from in vitro-grown plants were recovered by different extraction methods, viz., hexanoic, ethanolic, and hot and cold aqueous. Chromatography–based metabolite profiling and chemical reaction methods revealed the presence of flavonoids, steroids, lipids, vitamins, among other antioxidant and antitumor biomolecules. Eicosanoic and tricosanoic acids, α-Tocopherol (vitamin E) and scutellarein were, for the first time, described in the Nidularium group. Ethanolic and aqueous extracts contained the highest phenolic content (107.3 mg of GAE.100 g−1) and 2,2-diphenyl-1-picryl-hydrazyl-hydrate (DPPH) radical scavenging activity, respectively. The immunomodulatory and antitumoral activities of aqueous extracts were assessed using specific tests of murine macrophages modulation (RAW 264.7) and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay against adrenocortical carcinoma cell line, respectively. The aqueous extract improved cell adhesion and phagocytic activities and phagolysossomal formation of murine macrophages. This constitutes new data on the Bromeliaceae family, which should be better exploited to the production of new phytomedicines for pharmacological uses.

Subject terms: Biotechnology, Field trials

Introduction

Bromeliaceae is a morphologically distinctive and ecologically diverse family, divided into eight subfamilies (Brochinioideae, Lindmanioideae, Tillandsioideae, Hechtioideae, Navioideae, Pitcairnioideae, Puvoideae and Bromeliodeae) based on morphological and molecular DNA data1. Almost the entire family is native to the American continent, with the exception of Pitcairnia feliciana (A.Chev), an endemic specie of West Africa2. Due to their wide distribution and abundance in tropical habitats, bromeliads represent a very important ecological component in many communities, with a direct impact on richness and diversity of fauna and flora3.

Bromeliads are also worldwide recognized for their ornamental value. In the past decades, it has become very popular as a garden plant, which increased the extraction pressures from natural populations. Brazil is the diversity center of Bromeliaceae, with 1,246 species cataloged to date, in which, 1,067 are endemic to the country4. Among these, six species are classified as vulnerable, three endangered and seven critically endangered, indicating threatened ecosystems according IUNC criteria5. Nidularium is a genus with high vulnerability to extinction and Nidularium procerum Lindm is one of the most prevalent bromeliads found in the Atlantic Rain Forest6. It is a polymorphic specie, with varying appearance in response to the environment, especially the coloration of the leaves and bracts involved. The populations are mainly concentrated on the coast, where they develop in isolation or in groups of 2–10 individuals7.

The bromeliad family has been used for centuries in Native American medicine8. More recent research has confirmed the beneficial effects of bromeliads supported by traditional medicine, such as improvement of digestive, diuretic and respiratory processes9,10. Other biological actions include relief of fever symptoms and diabetes mellitus11, as well as anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic proprieties, being able to inhibit the influx of pleural neutrophils and mononuclear cells in allergy-induced mice and, also, decrease the number of eosinophils by inhibiting PAF and eotaxin-induced eosinophil chemotaxis12,13. In addition, bromeliad extracts are reported and used as antitumoral agents. Bromelain and fastuosain — a complex natural mixture of proteolytic enzymes described in the group — was demonstrated to induce the apoptosis pathway of human epidermoid carcinoma and melanoma cells14,15. Phytochemical compounds present in bromeliads family were also shown to affect cell adhesion molecules involved in other pathways of carcinoma cells growth16.

In the current scenario of vulnerability caused by human exploitation, it is necessary to use alternative methods that allow cultivation of plant species. Thus, in vitro plant tissue culture represents an ecological alternative to obtain competent explants (plant parts) under controlled conditions. This cultivation system allows the obtaining of several compounds with pharmacological interest without affecting natural population levels. In addition, micropropagated plants produce secondary metabolites at an early stage of growth17, which can be a way to provide rapid propagation of a large number of uniform plants, without being affected by adverse natural factors, such as climate, season, diseases and slow plant growth18. This allows for a technology alternative for rapid production of pharmacological compounds that can be utilized for medicinal purpose.

Recent studies have revealed the pharmacological properties of N. procerum. Amendoeira et al.12, Amendoeira et al.19 and Vieira-de-Abreu et al.13 reported that extracts of N. procerum have analgesic, anti-inflammatory and antiallergic properties with nontoxic activities, making it an attractive candidate for future drug development. However, the phytochemical composition of N. procerum remains poorly studied. Only a study conducted by Williams (1978)20 reported the flavonoid composition of leaves of Bromelia spp. including N. procerum, which observed the presence of quercetin. Here, crude extracts from the leaves of in vitro cultivated N. procerum were analyzed by diverse chemical analysis, including phytochemical screening by colorimetric tests, target compounds by gas chromatography assays (GC), chlorophyll quantification, total phenolic compounds and individual phenols by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), and antioxidant activity. In addition, for the first time, the immunomodulatory and antitumoral activities of aqueous extract of N. procerum leaves were assessed using specific tests of murine macrophages modulation and MTT assay against adrenocortical carcinoma, a cancer with rare treatment.

Results and Discussion

Phytochemical screening

The phytochemical screening of crude extracts from the leaves of in vitro cultivated N. procerum revealed the presence of some secondary metabolites, according to the solvent used (Table 1). The Ethanolic (ET), Hot Aqueous (HA-100 °C) and Cold Aqueous (CA-25 °C) extracts showed positive results for alkaloids, with the appearance of red orange precipitated complexes on Dragendorff test. Two qualitative tests (i.e., Wagner and Mayer) were also carried out for this chemical group, confirming the positive results. Furthermore, the aqueous extracts showed defined turbidity (HA) and precipitate (CA), whereas ET showed only opalescence, indicating that aqueous extracts could also be effective for alkaloid extraction.

Table 1.

Preliminary screaning of hexane, ethanolic and aqueous extracts of Nidularium procerum Lindm shoots.

| Metabolites | Hexane Extract | Ethanolic Extract | Hot Aqueous Extract | Cold Aqueous Extract |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkaloids Dragendorff | − | + | ++ | +++ |

| Alkaloids Wagner | − | + | ++ | +++ |

| Alkaloids Mayer | − | + | ++ | +++ |

| Reducing Sugars | − | − | − | − |

| Quinones | − | − | − | − |

| Saponins | − | − | − | − |

| Mucilages | − | − | − | |

| Coumarins | − | − | − | − |

| Steroids/Triterpenoids | ++ | + | − | − |

| Resins | − | − | − | − |

| Flavonoids | + | ++ | ++ | |

| Tannins | − | ++ | + | + |

Blank spaces mean that the test was not performed on the extract.

(+) small quantity positive response was obtained for the chemical group in the extract.

(++) medium quantity positive response was obtained for the chemical group in the extract.

(+++) positive response of greater quantity was obtained for the chemical group in the extract.

(−) negative response was obtained for that chemical group in the extract.

The Liberman-Buchard test revealed the presence of steroids/triterpenoids in Hexanoic (HE) and ET extracts. HE showed the formation of yellow color, indicating the possible presence of a methyl group on carbon 1421. In the ET, a green color was observed, related with a carbonyl function in carbon 3 and double bound between carbons 5 and 6 or 7 and 8 in the extracted compounds22.

The flavonoid group was observed in ET, HA and CA extracts, with the appearance of yellowish green and intense yellow, respectively, by Shinoda test. In addition, the ferric chloride assay confirmed the presence of tannins in these extracts. The ET showed a blueish black color, indicating the presence of pyrogallol tannins or hydrolysable tannin, which generates gallic acid or ellagic acid when hydrolyzed by acids, bases or appropriated enzymes23. Finally, both aqueous extracts showed intense green color, referring to the presence of pyrocatecholic tannins (condensed tannins), formed by condensation of two or more flavanols, which are not hydrolyzed by acids, bases or specific enzymes23.

These secondary metabolites found in the N. procerum extracts are important due to their biological activities. Alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins and other biomolecules are known for their antioxidant, antifungal, anticancer, antiviral, anti-inflammatory and antiophidic activities24–26. Moreover, previous studies reported the presence of sterols, di and triterpenes, phenolic compounds, flavonoids, lignin, saponins, coumarins and cinnamic acids derivatives in other species grown under natural conditions of the Bromeliaceae family6,27.

Gas Cromatography – Mass Spectroscopy (CG-MS)

GC-MS was carried out in order to describe and quantify the compounds found in a solvent polarity gradient, chosen according to permission of method. A total of 43 phytocompounds were found (Table 2). These compounds belong to different chemical classes, including hydrocarbons, esters of fatty acids, steroids/triterpenes, aldehydes, amides, vitamins and flavones. The highest number of compounds (28) was evidenced in chloroform leaf extract (CHL), followed by methanol (ME) (11) and hexane (4). The major compounds found were hydrocarbons (32,5%), esters of fatty acids (21%) and steroids/triterpenes (9,3%). Some of these compounds, such as tetrapentacontane, tetradecane, stigmasterol, neoftadiene (7,11,15-trimethyl-3-methylidenehexadec-1-ene), n-hexadecanoic acid, oleic acid and octadecanoic acid, have already been reported from leaves extracts of other plant species28. Steroids (β-cytosterol and stigmasterol) and lipids (palmitic acid, oleic acid, γ-tocopherol, α-tocopherol) were described in Bromelia Laciniosa Mart. ex Shult. & Schult.f, Neoglaziovia variegata Mez and Encholirium spectabile Schult. & Schult2, while cyclolaudenol triterpene was reported in Tillandsia fasciculata Sw. hexanoic extract29.

Table 2.

Main compounds found in different extracts of N. procerum Lindm by GC-MS.

| Coumpounds | Chemical Class | Area | m/z | Retencion time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chloroform | ||||

| 7,11,15-trimethyl-3-methylidenehexadec-1-ene | Hydrocarbon | 5329 | 68.0 | 19.813 |

| Methyl hexadecanoate | Fatty Acid Ester | 10533 | 74.0 | 21.079 |

| Tetradecan-2-ylbenzene | Hydrocarbon | 59459 | 105.0 | 22.299 |

| Methyl (9E,12E)-octadeca-9,12-dienoate | Fatty Acid Ester | 2038 | 67.0 | 23.357 |

| 1-hexadecanoyloxy-3-hydroxypropan-2-yl)hexadecanoate | Fatty Acid Ester | 24428 | 57.0 | 25.871 |

| (Z)-octadec-9-enamide | Amide | 35867 | 59.0 | 26.662 |

| 1-iodotriacontane | Hydrocarbon | 38790 | 57.0 | 27.020 |

| (2-hydroxy-3-octadecanoyloxypropyl) octadecanoate | Fatty Acid Ester | 9716 | 57.0 | 28.218 |

| Tetracontane | Hydrocarbon | 56949 | 57.0 | 29.220 |

| (Z)-9-Octadecenoic acid 1,2,3-propanetriyl ester | Fatty Acid Ester | 14734 | 55.0 | 29.954 |

| (E)-octadec-9-enal | Aldheyde | 14614 | 55.0 | 30.112 |

| (1R,4R)-3,3,4-trimethyl-4-(4-methylphenyl)cyclopentan-1-ol | Hydrocarbon | 3318 | 147.0 | 30.717 |

| (Z)-docos-13-enamide | Amide | 56502 | 59.0 | 31.153 |

| 3-[(E)-dodec-2-enyl]oxolane-2,5-dione | NC* | 10118 | 67.0 | 31.158 |

| 2-methyl-3-(4-propan-2-ylphenyl)propanal | Aldheyde | 39439 | 133.0 | 31.253 |

| 1-chloroheptacosane | Hydrocarbon | 51728 | 57.0 | 31.267 |

| 2-octyl-3-pentadecyloxirane | Hydrocarbon | 9077 | 55.0 | 31.270 |

| 3,4-dihexyl-7,7-dimethylcyclohepta-1,3,5-triene | Hydrocarbon | 18042 | 119.0 | 31.398 |

| 12-[(2S,3R)-3-octyloxiran-2-yl]dodecanoic acid | Hydrocarbon | 6008 | 67.0 | 31.655 |

| 4-methyl-2-[(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)methylsulfanyl]-1H-pyrimidin-6-one | NC | 67968 | 133.0 | 31.944 |

| Tetrapentacontane | Hydrocarbon | 88322 | 57.0 | 32.247 |

| Dotriacontane | Hydrocarbon | 14947 | 57.0 | 34.587 |

| 4-O-(2,2-dichloroethyl) 1-O-undecyl (E)-but-2-enedioate | Fatty Acid Ester | 26373 | 69.0 | 34.595 |

| α-Tocopherol-β-D-mannoside | Vitamin | 10086 | 165.0 | 35.329 |

| 5,6,7-trimethoxy-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)chromen-4-one | Flavone | 52630 | 327.0 | 36.140 |

| β sitoesterol | Steroid/Triterpene | 2386 | 135.0 | 38.729 |

| Cyclolaudenol | Steroid/Triterpene | 7665 | 207.0 | 41.783 |

| Stigmasterol | Steroid/Triterpene | 34250 | 95.0 | 43.329 |

| Methanol | ||||

| 1-(4-hydroxy-2-methylphenyl)ethanone | Acetophenone | 66807 | 150.0 | 13.982 |

| 2-(hydroxymethyl)-2-nitropropane-1,3-diol | Alcohol | 25556 | 57.00 | 16.115 |

| Trehalose | Saccharide | 56984 | 73.00 | 19.635 |

| Methyl hexadecanoate | Fatty Acid Ester | 13085 | 74.00 | 23.918 |

| Methyl (9E,12E)-octadeca-9,12-dienoate | Fatty Acid Ester | 3758 | 67.00 | 26.202 |

| Methyl octadeca-9,12,15-trienoate | Fatty Acid Ester | 7985 | 79.00 | 26.292 |

| (4R)-2-methylpentane-2,4-diol | Alcohol | 10890 | 59.00 | 5.676 |

| 1-(3-methoxyphenyl)ethanone | Acetophenone | 1754 | 44.00 | 14.113 |

| 2-chloro-4-methylpentan-3-ol | Alcohol | 7720 | 57.00 | 16.126 |

| β-D-galactopyranosyl-(1 → 4)-D-glucose | Saccharide | 11882 | 73.00 | 19.655 |

| [(E)-henicos-10-en-11-yl]benzene | Hydrocarbon | 6891 | 118.0 | 24.983 |

| Hexan | ||||

| Tetradecan-2-ylbenzene | Hydrocarbon | 12199 | 105.0 | 20.874 |

| Tetrapentacontane | Hydrocarbon | 42750 | 57.0 | 34.579 |

| α-Tocopherol-β-D-mannoside | Vitamin | 42982 | 165.0 | 35.317 |

| Stigmasterol | Steroid/Triterpene | 77970 | 95.0 | 43.328 |

*NC – Not Classified.

The most commonly foun sterols in plants include campesterol, sitosterol and stigmasterol30. Stigmasterol, in particular, has been investigated for its pharmacological potential, including cytotoxic, antioxidant, antitumoral, antimutagenic, among other herbal approaches to pathological states in principles and practice of phytotherapies31. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, it is the first time that some important compounds, already described in the literature in other plant species, were reported in the Nidularium group. These include α-Tocopherol (vitamin E) and the 5,6,7-trimethoxy-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)chromen-4-one flavone, also known as scuttelarein. Previously, α-Tocopherol was reported in four species of the family B. laciniosa (1.8% content in hexane leaves extract), N. variegate (1.5% content in hexane leaves extract), E. spectabile (0,9% content in hexane leaves extract) and Ananas erectifolius (31.4 mg/Kg of fiber)2,32. The presence of vitamin E in N. procerum crude extracts increase the antioxidant and nutritional importance of the specie. In addition, scutellarein, previously found in Pitcairnia darblayana Sallier, Pitcairnia poortmanii André, Pitcairnia xanthocalyx Mart., Pitcairnia corallina Linden at André, Pitcairnia punicea Schiedw20 and Bromelia pinguin L. bromeliads33, were also related as anticancer agent against fibrosarcoma cells, by induction of cells apoptosis pathway34.

Lipid profile – gas cromatography (GC-MS)

The lipidic profile of N. procerum was investigated in the same apolar extractors used in GC-MS assay, whereas in the polar phase, it was analyzed in aqueous solvents, used in biological tests. The major identified constituents were Linolelaidic acid methyl ester (C18:2 – Omega 6), Methyl palmitate (C16:0 – Palmitic Acid), Cis-9-Oleic acid methyl ester (C18:1 – Oleic acid) and ɣ-Linolenic acid methyl ester (C18:3 – Gamma linolenic acid/Omega 6) (Table 3). Omega-6 Linolelaidic acid, an isomer of Linoleic acid found in spinach, broccoli, potatoes soya bean, cotton seed oil and sunflower oil35, was the major component found in the extracts. Furthermore, palmitic, oleic and ɣ-Linolenic acids are lipidic compounds commonly detected in Bromeliads36

Table 3.

Percentage of fatty acid in relation to the total fatty acids present in the hexane, chloroform, hot aqueous and cold aqueous extracts of fresh N. procerum Lindm plants multiplied on MS after 90 days of in vitro culture.

| Esters obtained from fatty acids | % of Fatty Acids | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hexane | Chloroform | HA | CA | |

| Methyl palmitate (C16:0) (Palmitic Acid) | zdc | 24.08 | 23.25 | 20.78 |

| Methyl palmitoleate (C16:1) (Palmitoleic Acid) | 5.87 | 2.86 | 5.36 | 6.66 |

| Methyl heptadecanoate (C17:0) (Margaric Acid) | ND | ND | 4.16 | ND |

| Methyl octadecanoate (C18:0) (Stearic Acid) | 4.62 | 9.10 | ND | 8.20 |

| cis-9-Oleic acid methyl ester (C18:1_cis9) (Oleic Acid) | 15.81 | 10.25 | 34.86 | 24.12 |

| Linolelaidic acid methyl ester (C18:2) (Omega-6) | 28.65 | 21.95 | 27.72 | 21.19 |

| Methyl Arachidate (C20:0) (Eicosanoic Acid) | 8.78 | 8.56 | 0 | 10.53 |

| ɣ -Linolenic acid methyl ester (C18:3 n-6) (Omega-6) | 14.71 | 15.54 | 4.64 | 8.52 |

| Methyl tricosanoate (C23:0) (Tricosanoic Acid) | 1.79 | 7.66 | ND | ND |

Other minor constituents detected were stearic and palmitoleic acids, previously reported in A. erctifolius L.B.Sm.32, B. pinguin L.36, B. laciniosa Mart. ex Shult. & Schult.f, N. variegata Mez and E. spectabile Schult. & Schult. bromeliads2. Moreover, eicosanoic and tricosanoic acids were also described (Table 3) and, to our knowledge, it was the first time these compounds are found in bromeliads leaves extracts. Eicoisanoic acid was already described in A. erectifolius bromeliad (24,2 mk/Kg in Fibers)32 and reported for having anticancer and antiinflamatory potential37; while tricosanoic acid was present in hexane extract of leaves from Ananas cosmosus bromeliad, which demonstrated potential cytotoxic against tumoral cell lines38.

Fatty acids play an important role in biological functions of living organisms, contributing to the prevention and treatment of some diseases. Diets with oleic, linolenic, linoleic and linoleic conjugates have been shown to reduce plasma cholesterol levels, in addition to affecting some physiological reactions, such as immune response and inhibition of tumor growth39, decreased risk of coronary heart disease, and protective action against stroke, age-related cognitive decline and Alzheimer disease40,41. Moreover, Omega-6 fatty acids has gained attention in medicine studies for showing potential in preventing sarcopenia, modulate cancer, atherosclerosis, obesity, immune function and diabetes40,42. This is the first time the lipid profile of N. procerum was described, improving the knowledge of its chemical compounds.

Chlorophyll quantification

Leaves of in vitro cultivated N. procerum showed a greater concentration of chlorophyll b (215.06 ± 14.8 µg.g−1 of fresh mass) than chlorophyll a (170.75 ± 18.5 µg.g−1 of fresh leaves). In comparison with Nidularium campo–alegrense Lem (56.4 ± 11.2 µg.g−1 fresh mass) and Aechmea ornate Baker (97.1 ± 11.2 µg.g−1 fresh mass) wild-type bromeliads43, N. procerum presented higher amounts of both chlorophylls. The photosynthetic mechanism of plants grown during in vitro culture is not completely active and the leaves have a reduced capacity to synthesize organic compounds44. Then, plants can compensate this failure with greater amounts of photosynthetic pigments, as they tend to increase its concentration, with reduced light intensity. Furthermore, bromeliads usually grow under the canopy and the leaves of shade plants often have higher content of chlorophylls than sun species45.

Despite the low ratio between chlorophylls a/b (0.79 ± 0.1 µg.g−1), when compared to N. campo – alegrense Lem (3.07 µg.g−1) and A. ornate Baker (2.94 µg.g−1) grown in normal conditions43, the higher amount of pigments can be related to the improvement of biological activity of the extracts. Chlorophyll compounds have been described as potential antioxidants with effective activity against lipidic peroxidation, DNA degradation and some cases of anemia46,47. Furthermore, recent works showed that chlorophyll derivatives, such as chlorophyllide, are also closely correlated to enhanced selectivity and improved cytotoxic activity against a range of carcinoma cells48.

Total phenolic content

The ET extract presented the highest concentration (107.27 mg of gallic acid/100 g), followed by CA (96.82 mg of GAE/100 g) and HA (78.57 mg of GAE/100 g). Similar results (70.73 mg of GAE/100 g) were reported in fresh fruit extracts of wild-type Bromelia anticantha Berto49.

In general, phenolics have gained attention due to their antioxidant, antimutagenic, anticancer and anti-inflammatory capacities50. The aromatic benzene rings with substituted hydroxyl groups are responsible for their biological activity through the capacity to eliminate or absorb free radicals, and to chelate reactive oxygen species molecules formators. Furthermore, the effectiveness is generally proportional to the number of hydroxyl (OH) groups present in their aromatic rings51.

Phenols content

The phenolic profile of aqueous extracts was evaluated in HPLC, in order to identify some antioxidants present in the solvents applied in the biological tests. The compounds were identified and quantified by comparing their retention times and absorption spectrum data in ultraviolet, which presented UV-band characteristic for gallic acid, p-coumaric acid, rutin, daidzein, quercetin, trans-cinnamic acid and genistein (Table 4).

Table 4.

Retention times of phenolic compounds present in aqueous extracts of N. procerum Lindm.

| Hot Aqueous extract of Nidularium procerum | Cold Aqueous extract of Nidularium procerum | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolic Compounds | Wavelength (nm) | Ret. Time | Area | Concentration (µg.g−1) | Ret. Time | Area | Concentration (µg.g−1) |

| Galic Acid 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoic acid | 275 | 3.39 | 252476 | 2.35 ± 0.27 | 3.39 | 279619.3 | 2.63 ± 0.45 |

| p-Coumaric Acid 3-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)-2-propenoic acid | 311 | 18.6 | 991292 | 4.39 ± 1.98 | 18.56 | 1117747.3 | 4.96 ± 0.22 |

| Rutin Quercetin-3-Rutoside | 357 | 21.7 | 129072 | 2.99 ± 0.33 | 21.72 | 143847 | 3.41 ± 0.23 |

| Daidzein Dihydroxyisoflavone | 260 | 23.4 | 161855 | BDL* | 23.1 | 170331 | BDL |

| Quercetin 3’,4’,5’,7–Tetrahydrixyflavon-3-ol | 370 | 25 | 30647 | 0.67 ± 0.09 | 25 | 33351.6 | 0.71 ± 0.04 |

| Trans-Cinnamic Acid Phenylacrylic acid | 275 | 25.3 | 322897 | 1.15 ± 0.09 | 24.87 | 272689.6 | 0.9 ± 0.2 |

| Genistein 5,7,4 Trihydroxyisoflavone | 325 | 25.7 | 244231 | 18.75 ± 3.36 | 25.9 | 252668.3 | 19.44 ± 4.41 |

*BDL – Below detection limit.

The main component found was the isoflavone genistein (19.4 µg.g−1)—a compound belonging to the flavonoids class of phenols. Other flavonoids were also detected, such as tannin gallic acid (2.6 µg.g−1), flavone rutin (3.4 µg.g−1) and flavonol quercetin (0.7 µg.g−1). With the exception of genistein, that is usually found in leguminous52, flavonoids are characteristic of the Bromeliaceae family, having been reported in Bromelia balansae Mez, E. spectabile Mart. ex Schult. & Schult.f among others53,54.

Flavonoids and phenolic acids, such the p-coumaric and trans-cinnamic found in this study, are known by their antioxidant, antibacterial, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, cardio and hepatoprotective effects55,56. Genistein, in particular, have already being described for having chemotherapeutic potential against some tumor lines, such as prostate and gastric cancer57,58.

Antioxidant activity of aqueous extracts

DPPH scavenging activity of hot aqueous (IC50: 0.18 ± 0.01 g.g−1 dry weight) and cold aqueous extract (IC50: 0.29 ± 0.01 g.g−1 dry weight) was dose-dependent, inhibiting up to 90% of free radicals and lower than the standard Trolox (IC 50: 18.30 ± 0.1 g.g−1 dry weight). However, HA extract also showed the highest value of Trolox equivalent (21.4 mg of Trolox.g−1 dry wheight), than CA extracts (18.83 mg of Trolox.g−1 dry weight) in 2,2-azinobis-3-ethyl-benzoatiazolin-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) assay. According to total phenolic content of N. procerum, HA showed a significant difference to CA (p < 0,05), which is closely related to its higher antioxidant potential between the extracts.

In the human body, antioxidants are efficient against some metabolic disorders that compromise the corporal homeostasis, such as lipidic and protein peroxidation, DNA degradation and cell membrane alteration59. The antioxidant power of N. procerum extracts can be attributed to the molecular structure of compounds, inparticular polyphenolics. They can inhibit free radicals and chelate metals, acting in entire oxidative process. Gallic acid has three hydroxyl radicals attached in its aromatic ring, which are considered to be closely related to its antioxidant, cytotoxic and antiproliferative potential60. In comparison to other phenolic acids, trihydroxilated derivatives displays grater biological activities than phenolic acids with fewer hydroxyl radicals in their molecular structure, such as p-coumaric, trans-ferulic and trans-caffeic acids61. Furthermore, compounds such as chlorophylls, alkaloids and some fatty acids, appear to contribute to the antioxidant activity, due to their ability in delocalize the unpaired electrons of free radicals62.

Immunomodulatory activity

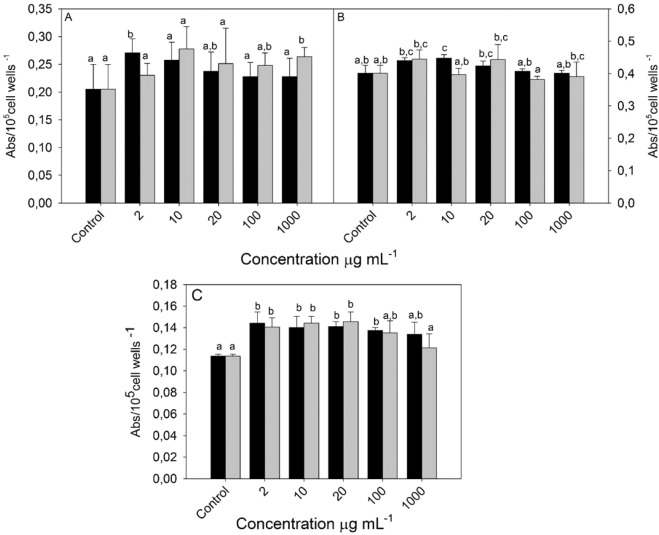

Many plant extracts have long been described as possessing anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory actions. The first line of human body defense against invading pathogens is the innate immune system, through macrophage cells. In the present study, murine macrophages were assessed in vitro by morphological indicators, such lysosomal volume, adhesion and phagocytic capacity, as well as metabolic activities of hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anion (Fig. 1). The macrophage adhesion response showed that the lowest concentration (2 µg.mL−1) of HA extract elicited a significant raise (p < 0.05) of about 32% of its activity (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, CA extract showed no significant impact at 2 µg.mL−1, but increased the adhesion capacity at a higher concentration tested (1000 µg.mL−1) in over 28% of isolated macrophages. The adhesion alteration capacity of cells may be linked to the biological compounds present in HA extract. Fatty acids and polyphenols, especially flavonoids and tannins, can change properties of the plasma membrane, altering its fluidity capacity, as well as the distribution of adhesion molecules within the plasma membrane, such β1 (CD29) and β2 (CD18/11a, b, c) integrins63. β1 (CD29) and β2 (CD18/11a, b, c) are molecules involved in mediate the adherence of phagocyte cells to endothelium cell receptors.

Figure 1.

Macrophages adhesion (A), Phagocytosis activity (B) and Phagolysosomal formation (C) of macrophages (cell line RAW 264.7) treated with hot aqueous extract (dark bars) and cold aqueous extract (gray bars) of Nidularium procerum Lindm. Values are mean ± SE (n = 12). Different letters on bars indicate significant differences by Tukey test (p < 0,05).

Cells treated with 10 µg.mL−1 HA elicited a significant increase in the phagocytic capacity of macrophages (p < 0.05), while in CA extract, no significant effect was observed at all concentrations tested (Fig. 1B). Similar results were reported in cells treated with methanolic extracts of Garcinia mangostana L. and Annona muricate L64. Triterpenes, isocoumarins, steroids and flavones described in this study (e.g., stigmasterol, rutin, daidzein and genistein) can induce activities in phagocytic cells, by activating surface receptors, such Fc gamma (FcɣRI, FcɣRIIA and FcɣRIIB), starting the “zippering” phagocytosis65 and also increasing the expression of complement receptors-CR1, CR3 and CR4-promoting the “sinking” phagocytosis66. Furthermore, unsaturated fatty acids have previously shown to improve phagocytosis ability67, and according to Table 3, HA presented higher content of unsaturated fatty acids (73%) than CA (60%).

The phagolysosomal formation of macrophages was stimulated when the cells were treated with lower concentrations of extracts (p < 0,05), raising ~25% of neutral red uptake in both HA and CA, at 20 µg.mL−1 (Fig. 1C). This held the dose-dependent response and the proportional increase rate observed previously in phagocytosis activity. Lysosomes play the role of digesting intracellular components and also break down phagocytosed material, through the fusion of phagosome to hydrolase-containing lysosomal vesicles68, improving the defense cell mechanism.

Reactive oxygen species, such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and superoxide anion (O2−), are generated in the first minutes of macrophage stimulation, during the so-called “respiratory burst”69. They are involved in the inflammation process, acting as efficient protectors; however, uncontrolled or excessive ROS production can further promote oxidative stress —a disruption in the redox balance system that contributes to damaging the body´s own cells and tissues70.

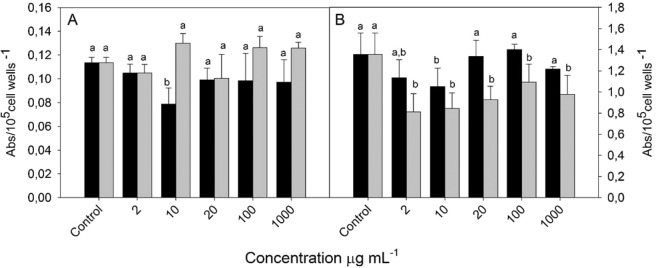

HA extract (10 µg.mL−1) was capable to inhibit 36% the production of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in macrophage cells (Fig. 2A), while CA did not differ in comparison to the control at any concentration tested (p < 0.05). In the same way, HA (10 µg.mL−1) significantly reduced 38% of the production of superoxide anion (Fig. 2B), and different from that described in the H2O2 assay, CA was capable of inhibiting the production of O2− in all concentrations (p < 0,05), with maximum reduction (40%) of activity at 2 µg.mL−1. This may be related to the potential of some flavonoids, such as rutin and quercetin, present in higher concentrations in CA extracts (3.41 and 0.71 µg.g−1 respectively) than HA, in the inhibition of xanthine oxidase and phosphoinositide 3-Kinase γ enzymes71. Furthermore, the higher concentration of H2O2 in relation to superoxide anion radical could be involved through the formation of enzyme-flavonoids hydrogen bonds, inhibiting the antioxidant activity of some peroxidase enzymes, such as catalase72.

Figure 2.

Hydrogen Peroxide Production (A) and Superoxide Anion Production (B) of macrophages (cell line RAW 267.4) treated with hot aqueous extract (dark ars) and cold aqueous extract (gray bars) of Nidularium procerum Lindm. Values are mean ± SE (n = 12). Different letters on bars indicate significant differences by Tukey test (p < 0,05).

Some molecules described in N. procerum extracts, especially flavonoids and derivatives, can act in different mechanisms of enzymes responsible for the oxidative burst in cells. The inhibition of ROS is related to their structure, the number and orientation of the hydroxyl group and the antioxidant potential of each compound; employing in its ability to permeate cell membrane and modulate the pathway signaling of NADPH-oxidase, phospholipase D, protein kinase C- (PKC) alpha, among others73. Plant extract compounds can also increase the expression of genes associated with the antioxidative system, such Cu/Zn-SOD, Mn-SOD, catalase, and GPx genes, suppressing oxidative stress by increasing antioxidant activity of enzymes74.

The ability to modulate all macrophage parameters found in N. procerum extract can be promising to help fight inflammation and even maintain cell homeostasis under different conditions. Leaf aqueous extract of N. procerum was also shown to interfere in different functions of host response capacity against injuries, such the inhibition of lipid body formation, PGE2 and cytokine production of in vivo pleural leukocytes12. Taken together, these data indicate that the substances described in the leaves of N. procerum proved to be efficient in modulating significant responses mediated by macrophages. This can be a potential alternative as a therapeutic agent applied in the prevention and treatment of pathologies related to the immune system. In addition, previous studies demonstrated that plant-derived compounds are able to alter the immunosuppressive status of patients, increasing antitumor immunity, promoting the proliferation of immune cells and accelerating macrophage phagocytosis75. To the best of our knowledge, there is no study on the anti-tumor activity of N. procerum extract. Studies were also carried out to evaluate the cytotoxic activity of in vitro cultured N. procerum Lindm against H295R cell line, a carcinoma with rare, heterogeneous malignancy and a very poor prognosis76.

Antitumoral activity

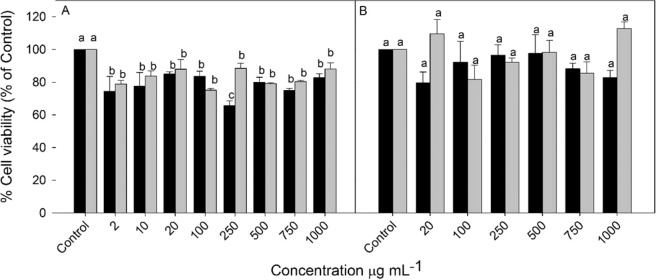

The key results obtained by MTT assay in H295R and the non-tumoral African green monkey kidney (VERO) cell lines exposed from 2 µg.mL−1 to 1000 µg.mL−1 for 24 h are summarized in Fig. 3. Both HA and CA showed significant decrease in tumor cell viability at all concentrations tested (Fig. 3A). The maximum mortality rate was 24,7% (CA at 100 µg.mL−1) and 34,4% -(HA at 250 µg.mL−1). On the other hand, there was no statistical difference among extracts and control in the viability of non-tumor cells (VERO) (Fig. 3B). The levels of extracts also showed no statistical differences, with no interaction among them. Molecules, such as phenolics described in this study, can either inhibit or stimulate the oxidative damage process, depending on the dose, structure, target molecule and environment77. In the present work, both HA and CA showed no cytotoxicity against normal cells, which makes these extracts promising as sources for the development of alternative drugs.

Figure 3.

Viability percentage of tumor cells (H295R) (A) and non-tumor cells (VERO) (B) treated with different concentrations of N. procerum Lindm aqueous extracts within 24 h. Values are mean ± SE (n = 12). Different letters on bars indicate significant differences by Tukey test (p < 0.05). Black bars: Hot Aqueous Extract (HA). Grey bars: Cold Aqueous Extract (CA).

Antitumoral activity has already been found in some species or Bromeliaceae, such as A. comosus L.78, Tillandsia recurvata Baker79 and Bromelia fastuosa Lindl.15. The antitumoral activity was attibuted to cysteine proteinases (e.g., bromelain and fastuosain) as well as flavonoids, including penduletin, cirsimaritin and HLBT-10033,79. Biological compounds are related to the suppression of some metastatic markers, resulting in regulation of mitogen activated protein kinase and protein kinase B80. Genistein, present in higher amounts in both HA and CA (Table 4), is also related to the inhibition of protein tyrosine kinase and topoisomerase II, and elimination of oxygen free radicals81,82, inhibiting the bioavailability of sex hormones, platelet aggregation, angiogenesis, as well as modulating the apoptosis of malignant cell lines83. The biological activities of genistein are also related to the intramolecular hydrogen bonding formed by 5-hydroxyl and 4-ketonic oxygen84,85. These characteristics may be related to the cytotoxic potential of HA and CA extracts.

Furthermore, some tannins, alkaloids, saccharides and fatty acids, especially polyunsaturated, have proved to be efficient as antitumoral agents, inducing autophagy of cells and other pathways86,87. Until now, there have been only a few studies in the biological activity of N. procerum and none of them included the chemical compounds related to it, nor their potential as antitumor agents. Adrenocortical carcinoma is a rare and aggressive neoplasm with pour prognosis88,89, in which most patients diagnosed with advanced disease had a median survival time of less than 12 months and a 5-year survival rate of less than 15% among patients with metastatic disease90. In this scenario, the biological activity reported for N. procerum shows potential for the development of alternative treatments against adrenocortical carcinoma, which needs to be further explored through isolation and/or microencapsulation of bioactive compounds.

Conclusions

The extracts obtained from the leaves of in vitro grown N. procerum were chemically characterized for the first time, showing the presence of phenolic compounds, steroids, fatty acids, polysaccharides, α-Tocopherol and scutellarein. These compounds showed good antioxidant activity and promoted the immunomodulation of murine macrophages. The crude extracts also showed potential against adrenocortical carcinoma cells, without cytotoxicity to non-tumoral cells, making it a potential candidate for alternative therapies against this tumoral line. However, further studies should be carried out to isolate and characterize N. procerum-derived compounds to improve cytotoxic activity as well as to prevent other human diseases caused by free radicals and other pathways.

Methods

Plant material and extraction

Plants were stablished and multiplicated in vitro according Lopes da Silva et al.91. Shoots (2 cm height) from clusters previously micropropagated in vitro were used as explants and subcultured in vitro to elongation and rooting for 90 days, free of plant growth regulators, up to the formation of a complete explant (basal and aerial part)-becoming available for extraction of leaves compounds, protocol adapted from Kim et al.80. Plantlets were removed from culture chambers and the leaves were cut into small pieces and 1 g of fresh leaf mass was macerated and extracted in 10 mL of specific solvent, over 24 hours, under 80 rpm agitation and 25 °C in a dark room. The extracts were filtered with Whatman n° 1 filter paper, lyophilized and stored at −20 °C for further characterizations and applications.

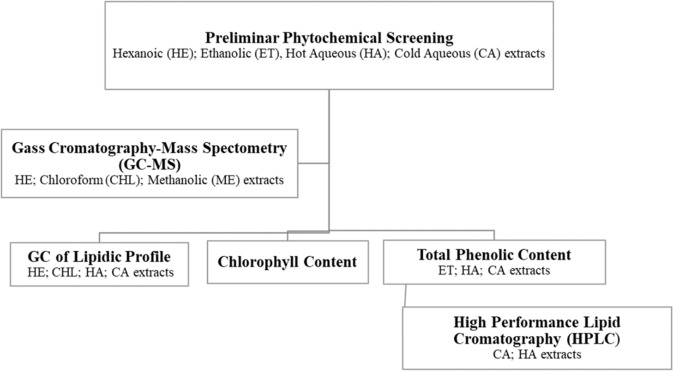

Chemical characterization of Nidularium procerum extracts

The chemical investigation of N. procerum compounds were carried out in different solvents, in order to detect the maximum range of substances extracted as summarized in the flowchart below (Fig. 4). The analyses were performed based on the results obtained in preliminary phytochemical screening and finally focused on aqueous extracts used in biological tests. The antioxidant, immunomodulatory and antitumoral potential of the aqueous fractions were explored due to their lack of toxicity and the low-cost of the process.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of methodologies used in chemical characterzation of different extracts of N. procum Lindm.

Phytochemical screening

The phytochemical tests were carried out in four different extracts from N. procerum: hexane (Analytical standard-VETEC), ethanolic (Analytical standard-VETEC), hot aqueous (100 °C) and cold aqueous (25 °C). The screening was performed according to Iqbal et al.92. Identification of alkaloids was determined using Dragendorff, Mayer and Wagner´s test, reducing sugars using Fehling´s reagent, quinones by Bornträger´s test, saponins by permanent foam appearance, mucilage by gelatinous consistency after cooled, coumarins using Bajlet´s test, steroids/triterpenoids using Liebermann-Buchard´s test, resins by precipitation test, flavonoid by Shinoda´s test and tannins/phenols using Ferric Chloride´s test.

Gas cromatography–mass spectrometry

The GCMS profiles of solvents with different polarity ranges (HE, CHL and ME) were obtained by electron impact with GC-MS-TQ Series 8040–2010 Plus (Shimadzu-Japan) equipped with a 95% PDMS and 5% Phenyl capillary column (model SH-Rtx-5MS; 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm). The temperature program started at 50 °C, maintained for 2 minutes and raised at a flow of 7 °C.min−1 up to 280 °C, which remained constant for 15 minutes, for a total of 47 min of analysis. Helium was the carrier gas used, at a 1 mL.min−1, 88.3kPa column press and split ratio of 1:40. The solvent cut off was 2.5 min. The mass spectrometry range was 30–500 (m/z), at an ion source temperature of 250 °C. The chemical compounds were identified by comparison of the mass spectra present in NIST98/2014 and Wiley 7 data library.

Lipid profile-gas chromatography

Fatty acid profile of CHL, HE, HA and CA extracts were analyzed using a Shimadzu chromatograph (GC 2010 Plus), a capillary column (SH-Rtx-Wax - Shimadzu: 30 m × 0.32 mm × 0.25 μm), flame ionization detector (FID) and split injection mode (1:10). The injector and detector temperatures were 240 °C and 250 °C, respectively. The oven temperature was programmed to start at 100 °C during 5 min, followed by an increase up to 240 °C at a rate of 4 °C.min−1 and maintained at this temperature for 5 min. The carrier gas was Helium at 32.5 cm3.min−1. The samples were prepared according to the official method (Ce 2–66) of the American Oil Chemist’s Society (AOCS, 1998) to convert triacylglycerol and free fatty acid of samples into fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs). FAMEs were identified by comparison with retention times of the standard mixture FAMEs (Supelco, MIX FAME 37, St. Louis, MO 63103, USA). The quantification of fatty acids was conducted by area normalization procedure. Results were expressed as percentage of each individual fatty acid present in the sample.

Chlorophyll quantification

Fresh leaves (5 g) were macerated in 10 mL acetone (P.A. VETEC). The solution was filtered with Whatman n° 1 filter paper and stored at −6 °C for five minutes. The absorbance was measured with spectrophotometry at 470, 662, 645, and 652 nm to chlorophyll a, b, relation between and chlorophyll a/b, respectively93. The assays were carried out in triplicate and the results were expressed in μg.g−1 of fresh weight.

Total phenol content

Total phenolic contents of ET, HA and CA extracts were determined using Folin-Ciocalteu method94 and the standard curve was performed using 0.39, 3.9, 7.8, 15.6, 31.2, 62.5 and 125 μg.mL−1 of gallic acid. The results were expressed in mg of gallic acid equivalent (GAE) in 100 g of fresh weight.

Phenolic content - high performance liquid chromatography

The phenolic content of aqueous extracts was separated in HPLC using an Agilent Technology 1200 Series system, coupled to a diode array detector (DAD) at wavelengths 235, 260, 275, 280, 290, 311, 357, 370 nm and a scanning from 190 nm to 600 nm. A ZorbaxElipse XDB-C18 (4,6 ×150 mm, 5-micron) column was used at 0,7 mL min−1 flow. The mobile phase was 2,5% acetic acid (solvent A) and methanol (solvent B). The elution gradient was carried out as follows: 90% A/10% B, 0–13 min; 75% A/25% B, 13–28 min; 15% A/85% B, 28–32 min; 10% A/90% B, 32–36 min. Chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, tocopherol, genistein, transcinnamic acid, catechin, rutin, p-coumaric acid, gallic acid, resveratrol and epicatechin (SIGMA) were used as standards. To obtain the calibration curve, all standard reagents were solved in mobile phase and used at 1, 2, 5, 8 and 10 ppm. The samples were microfiltered trough a hydrophilic membrane GV (Durapore) made of polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF), with a pore size of 0,22 μm. The resulting chromatogram values were plotted and a linear equation was generated by calculating the average of triplicate runs for each compound. The equations were used to quantify the phenolic compound contents of the samples. The injection volume was 10 µL. All the assays were also performed in triplicate.

In vitro antioxidant activity

Scavenging ability on DPPH

The antioxidant potential of the aqueous extracts was determined by their ability of quenching the free radical DPPH69. A Trolox (Sigma) standard solution was diluted from 0.25 to 25 mg/ml and used as positive control to the assay, mixing 200 μL of each concentration in 800 μl of 0.004% methanol solution of DPPH. After 30 min of incubation in absence of light at room temperature, the absorbances were read against blank at 517 nm using a SP-2000 spectrophotometer. The same protocol was used for the HA and CA treatments. DPPH solution was used as negative control with the solvent extraction. Tests were carried out in triplicate and the percentage of free radical inhibition was calculated by the following Eq. (1):

| 1 |

Where Ablank is the negative control and Asample is the absorbance of extracts. The results were expressed in extract concentration producing 50% inhibition (IC 50%), calculated from the graph of the DPPH scavenging effect against the extract concentration.

ABTS assay

The ABTS assay was carried out using a radical cation decolorization protocol95. The ABTS radical had to be pre-formed by the reaction between 5 mL ABTS 7 mM (Sigma) with 88 μL of 140 mM potassium persulfate, stored in the dark at room temperature for 16 hours. The ABTS solution (1 mL) was previously diluted in 50 mL of ethanol P.A. (Alphatec) to obtain an absorbance of 0.700 at 734 nm. In absence of light, 10 μL of each aqueous plant extract were added to 500 μL ABTS solution. After 6 minutes, the absorbance was read in the spectrophotometer (SP 2000) at 734 nm. Distilled water was used as blank and as negative control. All measurements were carried out in triplicates. The scavenging capability of tests compounds was calculated using the following Eq. (2):

| 2 |

Where λ734-Sample is the absorbance of control without radical scavenger and λ734-Control the remaining ABTS in the presence of scavenger. Trolox was used as standard.

Immunomodulatory activity

Macrophage activity was assessed by its reactive oxygen species production - superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide, cell adhesion, phagocytic efficiency and phagolysosomal formation96. Murine macrophages cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM-Sigma Aldrich) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS - Gibco and 1% antibiotic solution (10.000 U.mL−1 penicilin and 10 mg.mL−1 streptomycin - Gibco®), maintained in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C until 80–90% confluence was reached. The cells were divided at 105 cells/well in 96-well plate (Biofil) and exposed into the following experimental groups: cells without treatment (C), Hot Aqueous (HA) and Cold Aqueous Extract (CA), both at concentrations 2, 10, 20, 100 and 1000 μg.mL−1 for 24 h at same conditions of growing. The analyses were performed in 12 repetitions.

Antitumoral activity

H295R and VERO cells were cultured in DMEM F-12 (Sigma Aldrich) medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 1% antibiotic solution (Gibco). They were incubated in a CO2 incubator at 37 °C, with humidified air (95%) and CO2 (5%) until 80–90% confluence was reached. The cells were divided in 105 cells/wells in a 96-well plate (Biofil) and exposed into the following experimental groups: cells without treatment (C), Hot Aqueous and Cold Aqueous Extract, both at concentrations 2, 10, 20, 100 250, 500, 750 and 1000 μg.mL−1 for 24 h at the same growing conditions. The analyses were performed in 12 repetitions97.

Statistical analysis

The data were expressed as mean ± standard error and analyzed by One Way Anova followed by Tukey´s test using Graph Pad Prism 6 software. Differences between means at the 5% of confidence interval (p < 0.05) were considered significant.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the financial support provide by CAPES and Dr. Emillio A. Herrera for proofreading and criticism on the manuscript.

Author contributions

C.R.S., V.O.A.T. and S.J.R.B conceived the study and designed the experiments. A.L.G., O.M., S.H.S. performed the experiments and analysed the data. I.R.B. and A.L.G. coordinate and performed the chromatography analyses. A.L.G., G.V.d.M.P., V.O.A.T., O.M., S.J.R.B. and S.H.S., drafted the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Versieux L, de M, Coffani-Nunes JV, Paggi GM, Da Costa AF. Check-list of bromeliaceae from Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. Iheringia - Ser. Bot. 2018;73:163–168. doi: 10.21826/2446-8231201873s163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Juvik Ole, J., Holmelid, B., Francis, G. & Andersen, H. L. Non-Polar Natural Products from Bromelia laciniosa, Neoglaziovia variegata and Encholirium spectabile (Bromeliaceae). Molecules, 10.3390/molecules22091478 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Smith, L. B. & Till, W. Bromeliaceae. Flowering Plants· Monocotyledons, 10.1007/978-3-662-03531-3_8 (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

- 4.Forzza RC, et al. New Brazilian Floristic List Highlights Conservation Challenges. Bioscience. 2012;62:39–45. doi: 10.1525/bio.2012.62.1.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinelli, G. & Moraes, M. A. Livro Vermelho da Flora do Brasil. (Instituto de Pesquisas Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro, 2013).

- 6.Manetti LM, Deiaporte RH, Laverde A. Secundary metabolites from Bromeliaceae family. Quim. Nova. 2009;32:1885–1897. doi: 10.1590/S0100-40422009000700035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tardivo RC, Cervi AC. O gênero Nidularium Lem. (Bromeliaceae) no Estado do Paraná. Acta Bot. Brasilica. 1997;11:237–258. doi: 10.1590/S0102-33061997000200012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Negrelle, R. R. B., Anacleto, A. & Mitchell, D. Bromeliad ornamental species: conservation issues and challenges related to commercialization. Acta Sci. Biol. Sci. 34 (2012).

- 9.Duke, J. A., Bogenschutz-Godwin, M. J., Ducellier, J. & Duke, P. A. K. Handbook of medicinal herbs. (CRC Press, 2002).

- 10.Rodrigues VEG, Carvalho D. Levantamento etnobotânico de plantas medicinais no domínio dos cerrados na região do Alto Rio Grande-Minas Gerais. Rev. Bras. Plantas Med. 2007;9:114–140. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whiterup KM, et al. Identification of 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaric Acid (HMG) as a Hypoglycemic Principle of Spanish Moss (Tillandsia usneoides) J. Nat. Prod. 1995;58:1285–1290. doi: 10.1021/np50122a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amendoeira Fabio C, et al. (a) Anti-inflammatory Activity in the Aqueous Crude Extract of the Leaves of Nidularium procerum: A Bromeliaceae from the Brazilian Coastal Rain Forest Anti-inflammatory Activity in the Aqueous Crude Extract of the Leaves of Nidularium procerum: A Brome. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2005;28:1010–1015. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vieira-de-Abreu A, et al. Anti-allergic properties of the bromeliaceae Nidularium procerum: Inhibition of eosinophil activation and influx. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2005;5:1966–1974. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rathnavelu V, Alitheen N, Sohila S, Kanagesan S, Ramesh R. Potential role of bromelain in clinical and therapeutic applications (Review) Biomed. Reports. 2016;5:283–288. doi: 10.3892/br.2016.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guimarães-Ferreira CA, et al. Antitumor Effects In Vitro and In Vivo and Mechanisms of Protection against Melanoma B16F10-Nex2 Cells By Fastuosain, a Cysteine Proteinase from Bromelia fastuosa. Neoplasia. 2007;9:723–733. doi: 10.1593/neo.07427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juhasz B, et al. Bromelain induces cardioprotection against ischemia-reperfusion injury through Akt/FOXO pathway in rat myocardium. Am. J. Physiol. Hear. Circ. Physiol. 2008;294:1365–1370. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01005.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ncube B, Ngunge VNP, Finnie JF, Staden J. Van. A comparative study of the antimicrobial and phytochemical properties between outdoor grown and micropropagated Tulbaghia violacea Harv. plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;134:775–780. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arikat NA, Jawad FM, Karam NS, Shibli RA. Micropropagation and accumulation of essential oils in wild sage (Salvia fruticosa Mill.) Sci. Hortic. (Amsterdam). 2004;100:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2003.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amendoeira FC, et al. (b) Antinociceptive effect of Nidularium procerum: A Bromeliaceae from the Brazilian coastal rain forest. Phytomedicine. 2005;12:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams CA. The systematic implications of the complexity of leaf flavonoids in the bromeliaceae. Phytochemistry. 1978;17:729–734. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)94216-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cook RP. Reactions of Steroids with Acetic Anhydride and Sulphuric Acid (the Liebermann - Burchard Test) Analyst. 1961;86:376–381. doi: 10.1039/an9618600373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiong, Q., Wilson, Æ. W. K. & Pang, Æ. J. The Liebermann-Burchard Reaction: Sulfonation, Desaturation, and Rearrangment of Cholesterol in Acid. 87–96, 10.1007/s11745-006-3013-5 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Elgailani, I. E. H. & Ishak, C. Y. Methods for Extraction and Characterization of Tannins from Some Acacia Species of Sudan. 17, 43–49 (2016).

- 24.Goietsenoven GV, et al. Amaryllidaceae Alkaloids Belonging to Different Structural Subgroups Display Activity against Apoptosis-Resistant Cancer Cells †. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:1223–1227. doi: 10.1021/np9008255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schrader KK, et al. A Survey of Phytotoxic Microbial and Plant Metabolites as Potential Natural Products for Pest Management. Chem. Biodivers. 2010;7:2261–2280. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201000041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cimmino, A., Masi, M., Evidente, M., Superchi, S. & Evidente, A. Amaryllidaceae alkaloids: Absolute configuration and biological activity. Chirality 486–499, 10.1002/chir.22719 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Andrighetti-Frohner CR, et al. Antiviral evaluation of plants from Brazilian Atlantic Tropical Forest. Fitoter. - Elsevier. 2005;76:374–378. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swamy MK, et al. GC-MS Based Metabolite Profiling, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of Different Solvent Extracts of Malaysian Plectranthus amboinicus Leaves. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017;2017:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2017/1517683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cantillo-Ciau Z, Brito-Loeza W, Quijano L. Triterpenoids from Tillandsia fasciculata. J. Nat. Prod. 2001;64:953–955. doi: 10.1021/np0100744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tao, Bernie, Y. Bioprocessing for Value-Added Products from Renewable Resources. Bioprocessing for Value-Added Products from Renewable Resources, 10.1016/B978-044452114-9/50024-4 (Elsevier Science, 2007).

- 31.Chaudhary J, Jain A, Kaur N, Kishore L. Stigmasterol: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2011;2:2259–2265. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marques G, Gutiérrez A, Del Río JC. Chemical characterization of lignin and lipophilic fractions from leaf fibers of curaua (Ananas erectifolius) J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007;55:1327–1336. doi: 10.1021/jf062677x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raffauf RF, Menachery MD, Le Quesne PW, Arnold EV, Clardy J. Antitumor Plants. 11. Diterpenoid and Flavonoid Constituents of Bromelia pinguin L. J. Org. Chem. 1981;46:1094–1098. doi: 10.1021/jo00319a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi X, et al. Scutellarein inhibits cancer cell metastasis in vitro and attenuates the development of fibrosarcoma in vivo. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015;35:31–38. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Talapatra, S. K., Talapatra, B. & Nicolaou, K. C. Chemistry of plant natural products: Stereochemistry, conformation, synthesis, biology, and medicine. Chapter 34 - Organic Phytonutrients, Vitamins and Antioxidants, 10.1007/978-3-642-45410-3 (Springer Nature, 2015).

- 36.Payrol JA, Martinez, Migdalia M, García Janet L. Extracto etéreo de frutos de Bromelia pinguin L. (piña de ratón) por el sistema acoplado CG-EM. Rev. Cuba. Farm. 2001;35:51–55. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arora S, Kumar G, Meena S. Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectroscopy Analysis of Root of an Economically Important Plant, Cenchrus Ciliaris L. From Thar Desert, Rajasthan (India) Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2017;10:64. doi: 10.22159/ajpcr.2017.v10i9.19259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arruda J, et al. Metabolic profile and cytotoxicity of non-polar extracts of pineapple leaves and chemometric analysis of diferent pineapple cultivars. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2018;124:466–474. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.08.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oomah BD, Mazza G. Health benefits of phytochemicals from selected Canadian crops. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1999;10:193–198. doi: 10.1016/S0924-2244(99)00055-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Macdonald, H. B. Conjugated Linoleic Acid and Disease Prevention: A Review of Current Knowledge Conjugated Linoleic Acid and Disease Prevention: A. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 37–41, 10.1080/07315724.2000.10718082 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Arsic, A., Stojanovic, A. & Mikic, M. Oleic Acid - Health Benefits and Status in Plasma Phospholipids in the Serbian Population. Serbian J. Exp. Clin. Res. 1–6, 10.1515/SJECR (2017).

- 42.Kim JH, Kim Y, Kim YJ, Park Y. Conjugated Linoleic Acid: Potential Health Benefits as a Functional Food Ingredient. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2016;7:221–224. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-041715-033028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Prado J, et al. Características fisiológicas de bromélias nativas da Mata Atlântica: Nidularium campo-alegrense Leme e Aechmea ornata Baker. Acta Sci. - Biol. Sci. 2014;36:101–108. doi: 10.4025/actascianimsci.v36i1.21641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cassana FF, Falqueto AR, Braga EJB, Peters JA, Bacarin MA. Chlorophyll a fluorescence of sweet potato plants cultivated in vitro and during ex vitro acclimatization. Brazilian Soc. Plant Physiol. 2010;22:167–170. doi: 10.1590/S1677-04202010000300003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goodchild DJ, Bjorkman O, Pyliotis NA. Chloroplast ultrastructure, leaf anatomy, and content of chlorophyll and soluble protein in rainforest species. Carnegie Inst. Washingt. 1972;71:102–107. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Durga, M. & Banu, N. Study of antioxidant activity of chlorophyll from some medicinal plants. Indian J. Res. (2015).

- 47.Marková, I. et al. Chlorophyll-Mediated Changes in the Redox Status of Pancreatic Cancer Cells Are Associated with Its Anticancer Effects. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Wang, Y. et al. Cytotoxic Effects of Chlorophyllides in Ethanol Crude Extracts from Plant Leaves. 2019 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Krumreich F, Correa D, Da Silva APC, Zambiazi SDS, Rui C. Composição Físico-Quimica e de Compostos Bioativos em Frutos de Bromelia antiacanha BERTOL. Rev. Bras. Frutic. 2015;37:450–456. doi: 10.1590/0100-2945-127/14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rondón M, et al. Preliminary phytochemical screening, total phenolic content and antibacterial activity of thirteen native species from Guayas province Ecuador. J. King Saud Univ. - Sci. 2018;30:500–505. doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2017.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Macêdo L, et al. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antibacterial activities and evaluation of cytotoxicity of the fractions obtained from Selaginella convoluta (Arn.) Spring (Selaginellaceae) Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2018;32:506–512. doi: 10.1080/13102818.2018.1431055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Graham, T. L. Handbook of Phytoalexin Metabolism and Action. Chapter 5 - Cellular Biochemistry of Phenylpropanoid Responses of Soybean to Infection by Phytophthora sojae, 10.1201/9780203752647 (Taylor & Francis, 1995).

- 53.Coelho RG, Queico C, Leite F, Andre C, Roge F. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant and Antimycobacterial Activities of Bromelia balansae (Bromeliaceae) J. Med. Food. 2010;13:1277–1280. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2009.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Santana Clara, R. R. et al. Phytochemical Screening, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activity of Encholirium spectabile (Bromeliaceae). Int. J. Sci. Nov-2012, 1–19 (2012).

- 55.Kumar S, Pandey AK. Chemistry and Biological Activities of Flavonoids: An Overview. Sci. World J. 2013;2013:1–16. doi: 10.1155/2013/162750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang T, Li Q, Bi K. Bioactive flavonoids in medicinal plants: Structure, activity and biological fate. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2018;13:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajps.2017.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kumi-Diaka J, Saddler-Shawnette S, Aller A, Brown J. Potential mechanism of phytochemical-induced apoptosis in human prostate adenocarcinoma cells: Therapeutic synergy in genistein and β-lapachone combination treatment. Cancer Cell Int. 2004;4:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matsukawa Y, Matsumoto K, Sakai T, Yoshida M, Aoike A. Genistein Arrests Cell Cycle Progression at G2-M. Cancer Res. 1993;53:1328–1331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miron VV, et al. Physical exercise prevents alterations in purinergic system and oxidative status in lipopolysaccharide ‐ induced sepsis in rats. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019;120:3232–3242. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gomes CA, et al. Anticancer Activity of Phenolic Acids of Natural or Synthetic Origin: A Structure-Activity Study. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:5395–5401. doi: 10.1021/jm030956v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Silva FAM, Borges F, Guimara C. Phenolic Acids and Derivatives: Studies on the Relationship among Structure, Radical Scavenging Activity, and Physicochemical Parameters †. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2000;48:2122–2126. doi: 10.1021/jf9913110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gan J, Feng Y, He Z, Li X, Zhang H. Correlations between Antioxidant Activity and Alkaloids and Phenols of Maca (Lepidium meyenii) J. Food Qual. 2017;2017:1–10. doi: 10.1155/2017/3185945. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim YS, et al. Induction of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 by water-soluble components of Hericium erinaceum in human monocytes. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011;133:874–880. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harun Nurul H, Septama AW, Jantan I. Immunomodulatory effects of selected Malaysian plants on the CD18/11a expression and phagocytosis activities of leukocytes. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2015;5:87–92. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(15)30150-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Underhill DM, Goodridge HS. Information processing during phagocytosis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012;12:492–502. doi: 10.1038/nri3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Campagne MVL, Wiesmann C, Brown EJ. Microreview Macrophage complement receptors and pathogen clearance. Cell. Microbiol. 2007;9:2095–2102. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Calder PC, Bond JA, Harvey DJ, Gordon S, Newsholme EA. Uptake and incorporation of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids into macrophage lipids and their effect upon macrophage adhesion and phagocytosis. Biochem. J. 1990;269:807–814. doi: 10.1042/bj2690807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Da Rosa RL, et al. Anti-inflammatory, Analgesic, And immunostimulatory effects of luehea divaricata mart. & zucc. (Malvaceae) bark. Brazilian J. Pharm. Sci. 2014;50:600–610. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tan H, et al. The Reactive Oxygen Species in Macrophage Polarization: Human. Diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016;2016:1–16. doi: 10.1155/2016/2795090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Castaneda OA, Lee SC, Ho CT, Huang TC. Macrophages in oxidative stress and models to evaluate the antioxidant function of dietary natural compounds. J. Food Drug Anal. 2017;25:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Selloum L, Reichl S, Müller M, Sebihi L, Arnhold J. Effects of Flavonols on the Generation of Superoxide Anion Radicals by Xanthine Oxidase and Stimulated Neutrophils. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2001;395:49–56. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Majumder D, Das A, Saha C. Catalase inhibition an anti cancer property of flavonoids: A kinetic and structural evaluation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017;104:929–935. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.06.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ciz, M. et al. Flavonoids inhibit the respiratory burst of neutrophils in mammals. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2012 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Hwang, K., Hwang, Y. & Song, J. Antioxidant activities and oxidative stress inhibitory effects of ethanol extracts from Cornus officinalis on raw 264. 7 cells. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 1–9, 10.1186/s12906-016-1172-3 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Matsushita M, Kawaguchi M. Immunomodulatory Effects of Drugs for Effective Cancer. Immunotherapy. J. Oncol. 2018;2018:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2018/8653489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kou K, et al. A case of adrenocortical carcinoma accompanying secondary acute adrenal hypofunction postoperation. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2018;16:1–4. doi: 10.1186/s12957-018-1326-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Khan NS, Ahmad A, Hadi SM. Anti-oxidant, pro-oxidant properties of tannic acid and its binding to DNA. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2000;125:177–189. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2797(00)00143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Báez R, Lopes MTP, Salas CE, Hernández M. In vivo antitumoral activity of stem pineapple (Ananas comosus) bromelain. Planta Med. 2007;73:1377–1383. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-990221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lowe HIC, Toyang NJ, Watson CT, Ayeah KN, Bryant J. HLBT-100: A highly potent anti-cancer flavanone from Tillandsia recurvata (L.) L. Cancer Cell Int. 2017;17:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12935-017-0404-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim, B. R., Ha, J., Lee, S., Park, J. & Cho, S. Anti-cancer effects of ethanol extract of Reynoutria japonica Houtt. radix in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells via inhibition of MAPK and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways. J. Ethnopharmacol. 112179, 10.1016/j.jep.2019.112179 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 81.Uckun FM, et al. Biotherapy of B-cell precursor leukemia by targeting Genistein to CD19-associated tyrosine kinases. Science (80-.). 1995;267:886–891. doi: 10.1126/science.7531365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Barnes, S. Anticancer Effects of Genistein Effect of Genistein on In Vitro and In Vivo Models of Cancer. J. Nutr. 777–783, 10.1093/jn/125.3 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 83.Ravindranath, M. H.; Muthugounder, S.; Presser, N.; Viswanathan, S. Anticancer Therapeutic Potential of Soy Isoflavone, Genistein. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1–57, 10.1007/978-1-4757-4820-8 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 84.Hiroshi Ogawara, Testu Akiyama, Shun-Ichi Watanabe, Norik Ito, Masato Kobori, Y. S. Inhibition of Tyrosine Protein Kinase Activity By Synthetic Isoflavones and Flavones. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo). 42, 340–343 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 85.Polkowski K, Mazurek AP. Biological properties of genistein. A review of in vitro and in vivo data. Acta Poloniae Pharmaceutica - Drug Research. 2000;57:135–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yildirim I, Kutlu T. Anticancer agents: Saponin and tannin. Int. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;9:332–340. doi: 10.3923/ijbc.2015.332.340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lee, H. J., Yoon, Y. S. & Lee, S. J. Mechanism of neuroprotection by trehalose: Controversy surrounding autophagy induction. Cell Death Dis. 9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Tripathy, S., Behera, A., Kumar, A. & Subudhi, K. Adrenocortical Carcinoma with Inferior Vena Cava Thrombus on F - FDG - PET - Computed Tomography. Indian J. Nucl. Med. 2019–2020, 10.4103/ijnm.IJNM (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 89.Parikh, P. P., Rubio, G. A., Farra, C. & Lew, J. I. Nationwide analysis of adrenocortical carcinoma reveals higher perioperative morbidity in functional tumors. Am. J. Surg. 216 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 90.Tran, T. B. et al. Actual 10-Year Survivors Following Resection of Adrenocortical Carcinoma. J. Surg. Oncol. 971–976, 10.1002/jso.24439 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 91.Lopes da Silva André L, et al. Micropropagation of Nidularium Innocentii Lem. and Nidularium Procerum Lindm (Bromeliaceae) Pakistan J. Bot. 2012;44:1095–1101. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Iqbal E, Salim KA, Lim LBL. Phytochemical screening, total phenolics and antioxidant activities of bark and leaf extracts of Goniothalamus velutinus (Airy Shaw) from Brunei Darussalam. J. King Saud Univ. - Sci. 2015;27:224–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jksus.2015.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wellburn AR, Lichtenthaler HK. Determinations of total carotenoids and chlorophylls a and b of leaf extracts in different solvents. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1983;11:591–592. doi: 10.1042/bst0110591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Singleton, V. L., Rossi, J. A. & Rossi, J A J. Colorimetry of Total Phenolics with Phosphomolybdic-Phosphotungstic Acid Reagents. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 16, 144–158 (1965).

- 95.Re R, et al. Antioxidant Activity Applying an Improved ABTS Radical CAtion Decolorization Assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999;26:1231–1237. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(98)00315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bonatto SJR, et al. Lifelong exposure to dietary fish oil alters macrophage responses in Walker 256 tumor-bearing rats. Cell. Immunol. 2004;231:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]