Abstract

Firearm carriage is a key risk factor for interpersonal firearm violence, a leading cause of adolescent (age \ 18) mortality. However, the epidemiology of adolescent firearm carriage has not been well characterized. This scoping review examined four databases (PubMed; Scopus; EMBASE; Criminal Justice Abstracts) to summarize research on patterns, motives, and underlying risk/protective factors for adolescent firearm carriage. Of 6156 unique titles, 53 peer-reviewed articles met inclusion criteria and were reviewed. These studies mostly examined urban Black youth, finding that adolescents typically carry firearms intermittently throughout adolescence and primarily for self-defense/protection. Seven future research priorities were identified, including: (1) examining adolescent carriage across age, gender, and racial/ethnic subgroups; (2) improving on methodological limitations of prior research, including disaggregating firearm from other weapon carriage and using more rigorous methodology (e.g., random/systematic sampling; broader population samples); (3) conducting longitudinal analyses that establish temporal causality for patterns, motives, and risk/protective factors; (4) capitalizing on m-health to develop more nuanced characterizations of underlying motives; (5) increasing the study of precursors for first-time carriage; (6) examining risk and protective factors beyond the individual-level; and, (7) enhancing the theoretical foundation for firearm carriage within future investigations.

Keywords: Firearm, Adolescent, Scoping review, Carriage patterns, Risk/protective factors, Motives

Introduction

Firearms are the second leading cause of death among U.S. children and adolescents, with 65% of pediatric firearm deaths resulting from interpersonal violence (Cunningham et al., 2018). Of the 1322 homicides that occurred among children and adolescents (age 1–17) in 2016, 64% resulted from firearms (CDC, 2017). Given a lack of progress reducing pediatric firearm injuries during the past decade, they now represent a critical public health endemic requiring increased attention (Christoffel, 2007), especially as firearm violence is associated with long-term health and social consequences, including repeat assault-injuries (Cunningham et al., 2015; Rowhani-Rahbar et al., 2015), subsequent firearm violence (Carter et al., 2015; Rowhani-Rahbar et al., 2015), long-term physical disabilities, substance use disorders, mental health issues (e.g., PTSD), and negative criminal justice outcomes (Carter et al., 2018a, b; Cunningham et al., 2009; DiScala & Sege, 2004; Greenspan & Kellermann, 2002; Rowhani-Rahbar et al., 2015; Walton et al., 2017). The costs of interpersonal firearm violence are substantial, with acute medical treatment for hospitalized firearm assaults alone averaging an estimated $389 million annually before factoring in acute care costs for patients discharged after treatment in the emergency department or the indirect costs that are associated with lost wages and productivity, long-term medical care, and associated criminal justice proceedings (Peek-Asa et al., 2017).

Firearm carriage is a key risk factor for adolescent bullying, physical fighting, assault, and violent injuries requiring treatment (Borowsky et al., 2004; Branas et al., 2009; Carter et al., 2013; Dukarm et al., 1996; Durant et al., 1995; DuRant et al., 1997; Forrest et al., 2000; Lowry et al., 1998; Pickett et al., 2005; Van Geel et al., 2014). Adolescents who carry firearms, as well as the peers surrounding them, are at increased risk for serious injury and death (Branas et al., 2009; Cheng et al., 2006; Cook, 1981; Durant et al. 1995; DuRant et al., 1997; Felson & Steadman, 1983; Loughran et al., 2016; Lowry et al., 1998; McDowall et al., 1992; Pickett et al., 2005). As a result, reducing firearm carriage among adolescent youth is among the key national health objectives outlined in Healthy People 2020 (HealthyPeople, 2018) and the Institute of Medicine and American Academy of Pediatrics have identified firearm violence prevention as a key research priority (Dowd & Sege, 2012; Leshner et al., 2013).

The objective of this study was to conduct a scoping review evaluating the existing literature related to contextual factors for adolescent firearm carriage. Specifically, this review synthesizes the published evidence on: (1) patterns; (2) motives; and, (3) risk and protective factors for adolescent firearm carriage. A secondary objective was to identify current gaps in the literature and establish a set of future research priorities. Understanding the current research findings, as well as the areas needed for future research, is critical to the development of effective public health interventions focused on reducing adolescent firearm carriage and associated negative health and social outcomes.

Methods

Search strategy

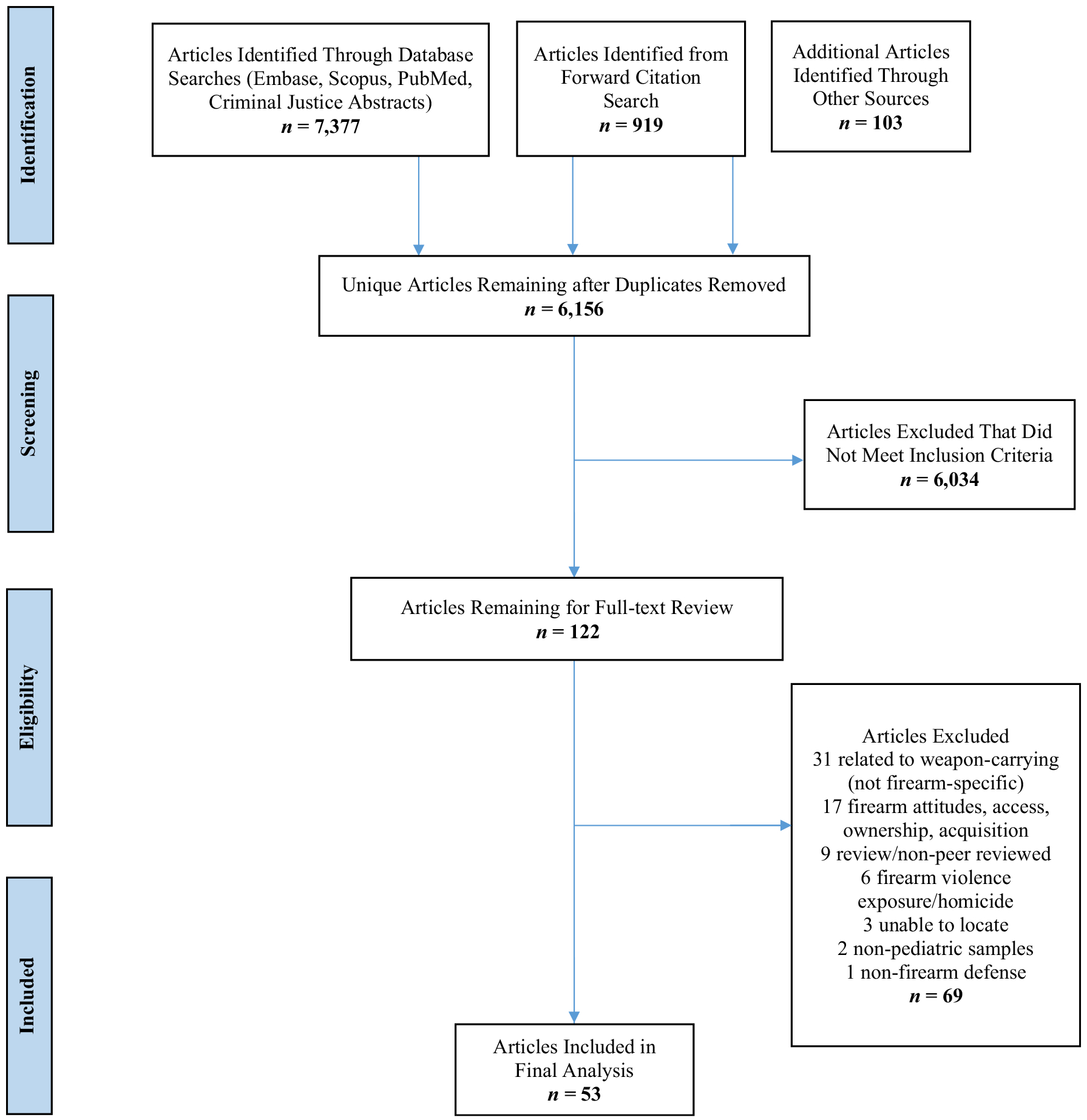

This scoping review (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Institute, 2015; Tricco et al., 2018) was conducted under the guidance of a medical research librarian at the UM Medical School (April–October; 2018). Scoping reviews systematically map large and diverse bodies of research to identify key concepts and gaps in the literature (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Grimshaw, 2010). Four databases were utilized, including PubMed, Scopus, EMBASE, and Criminal Justice Abstracts. A forward citation search was conducted (October 2018) to identify additional published articles. Reference sections of relevant studies were also reviewed to identify additional eligible studies. The initial search was limited to English-language articles published between January 1, 1985 and April 8, 2018. No limitations were placed on study design, although grey literature was excluded. Detailed search strategy is provided in “Appendix 1”. The Preferred Reporting Items for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) flow diagram describing search strategy, study selection, and data abstraction is outlined in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram

Study selection

Initial results were compiled in Endnote; duplicate articles were removed. The senior author (P.C.) conducted an initial title screen with a small set of articles (* 4%) to assess search quality. Two reviewers (S.O., C.M.) independently conducted a title/abstract review of the de-duplicated articles to assess inclusion eligibility. Discrepancies underwent full text review and were resolved by consensus/third party review. English-language articles reporting empirical research characterizing carriage patterns, motives, and/or risk/protective factors underlying firearm carriage among pediatric populations (age \ 18) were included. Given limited prior research, quantitative studies, as well as qualitative studies providing contextual information about carriage, were included. Articles were excluded if they did not focus specifically on firearm carriage (e.g., focused on weapon carriage or ownership), if they characterized non-U.S. populations, or if they focused exclusively on non-powder discharge firearms (e.g., air guns). Published reviews, narratives, and opinion articles were excluded. Articles reporting only carriage rates but not any of the other inclusion criteria were excluded. Research studies characterizing any portion of the pediatric population were included, while those conducted exclusively among adults (age > 17) were excluded.

Data abstraction, synthesis, quality assessment, and analysis

Full text review was independently conducted by two authors (S.O., C.M.). Data were abstracted using a standardized form, all entries were verified for accuracy, and discrepancies were resolved through consensus. Studies were classified as characterizing: (1) Patterns of firearm carriage (and/or initiation of firearm carriage); (2) Motives for firearm carriage; and/or, (3) Risk and protective factors for adolescent firearm carriage (i.e., factors that increased/decreased the propensity to carry firearms). For studies fitting more than one category, data were included in both data tables with relevant results. Abstracted data elements included study design, sample size, study population/setting, carriage rates, outcomes/dependent variables measured, results, and limitations. As recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins, 2011), non-randomized trials/studies were assessed for methodological quality using an adapted version of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) (Wells et al., 2000). The NOS (see “Appendix 2”) assesses quality on a 9-point scale, with scores of 7 or above considered high quality (Lei et al., 2015). Quality assessments were completed independently by two reviewers (S.O., C.M.), with discrepancies resolved through group consensus. Scoping review results are described qualitatively and in evidence tables. A meta-analysis was deemed inappropriate given the significant heterogeneity in study designs, populations, and measures. Inter-rater reliability was not calculated as all data was discussed collectively and consensus reached on all studies.

Results

Search results

The initial search identified 7377 articles. In addition, 919 articles were identified from the forward citation search and 103 were identified by expert submission/hand search. After duplicate removal (n = 2243), 6156 unique articles remained. Title/abstract review excluded 6034 studies with 122 remaining for full-text review. Of these, 69 were excluded: 31 were related to weapon-carriage (i.e., not firearms), 17 focused only on firearm attitudes, access, acquisition, or ownership, 9 were review articles or non-peer reviewed publications, 6 focused on firearm homicide or violence exposure and not carriage, 3 were not able to be located, 2 were conducted among non-pediatric samples, and 1 focused on non-firearm defense. Of the 53 included studies (Tables 1, 2, 3), 15 investigated carriage patterns (Table 1), 13 examined carriage motives (Table 2), and 39 characterized risk and protective factors (Table 3). Twenty-nine were cross-sectional, 17 were longitudinal cohort studies, 6 were qualitative, and one was a case–control design.

Table 1.

Articles reporting data on age of onset for firearm carriage and patterns of firearm carriage

| Article | Design | Sample size | Study sample and setting | Unique attributes | Key results for patterns of carriage | Limitations | Nos score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arria et al. (1995) | Cohort Surveyed annually for 5 years |

1714 | Students from 43 classrooms within 19 public schools from 5 districts in Baltimore, MD | M age (w1) 9 M age (w5) 13 50% Male 73% Black 26% White |

Past 1-year carriage = 10% (male); 1% (female). Rates of gun carriage increased across waves of data, starting at < 2% (w1) and increasing to 10% (male) and 1% (female) by wave 5 Less lethal weapon carriage (stick, knife) was associated with initiating carrying a gun at later waves across multiple waves |

Limited generalizability Single city Younger adolescent sample Missed students who may have dropped out at later waves Self-report data |

6 |

| Ash et al. (1996) | Qualitative Semi-structured interviews |

63 | Youth offenders recruited from 5 detention centers in Atlanta, GA | Ages 13–18 M age 15.7 67% Male 66% Black 34% White |

Patterns of carriage: Identified 4 distinct carrier types Non-carriers (n = 14): 71% of this group owned a gun Intermittent carriers (n = 14): Defined as having weeks and/or months without carrying; each owned ≥ 1 gun Part-time carriers (n = 11): Carried more frequently than Intermittent carriers and had increasing frequency over time in response to stressors (e.g., friend was shot) Constant carriers (n = 24): Defined as carrying all/most of the time; had carried constantly since acquiring a gun Small minority of carriers decreased carriage over time (n = 6) Purposeful acquisition of first firearm positively correlated with becoming frequent/constant carriers (p < 0.05) |

Limited generalizability Nonrandom convenience sample of youth offenders from single city Self-report data Small sample |

6 |

| Beardslee et al. (2018a) | Cohort Pittsburgh Youth Study Analysis from 6-month surveys (3-year; grade 2–4) and 12-month surveys (age 10–17) |

485 | Random sub-sample of male participants from youngest cohort of large school-based longitudinal study in Pittsburgh, PA | 100% male 56% Black 41% White Excluded non-White/Black participants |

Lifetime carriage = 27% (Black); 12% (White): Black youth more likely to carry in adolescence than White youth (OR = 3.3); Youth with higher levels of conduct problems and peer delinquency at earlier childhood waves, as well as those with increases in conduct problems across early childhood, were more likely to initiate gun carriage prior to age 18 Examining whether racial differences in carrying were due to differential exposure to risk factors or differential sensitivity, study found more support for differential exposure, with 60% of the race effect on carriage being attributable to either initial peer delinquency levels or initial levels of conduct problems |

Limited generalizability Limited to male Black/White youth sample Single city sample Self-report data. Small sample size may limit ability to detect group differences in gun carriage predictors |

6 |

| Beardslee et al. (2018b) | Cohort Pathway to Desistance Study: Youth surveyed every 6-month for 3 years then every 12-month for 4 years |

1170 | Male youth offenders recruited from court system in two counties; one in AZ (Maricopa) and one in PA (Philadelphia) | Ages 14—19 at baseline 100% male. 42% Black 34% Hispanic 19% White 100% offenders 70% on active probation at baseline |

Across 10 waves, carriage rates ranged from 15% (w1) to 10% (w10) with non-linear decrease; peak gun carriage was 17% at w7 data collection (i.e., 4 years after baseline; mean age 21) Youth with gun violence exposure (witness/victim of gun violence) were 43% more likely to engage in gun carriage at the next wave after controlling for time-stable and time-varying (exposure to peers who carried; exposure to peers engaged in other criminal acts, developmental changes, changes in gun carrying from incarceration or institutionalization) covariates. No evidence that non-gun violence exposure conferred same risk |

Limited generalizability Male sample of juvenile offenders in two states Self-report data Youth offenders likely have fluctuations in carrying over time |

6 |

| Dong and Wiebe (2018) | Cohort NLSY97 administered annually between 1997 to 2011 and then biennially (16 waves) |

1585 | Youth living in urban areas (as defined by Census criteria) at wave 1 data collection | Data from the 1997 Nat. Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY97) Age 14.27 (SD1.49) 76% Male 29% Black 26% Hispanic 44% White |

27.1% lifetime handgun carriage incidence 4–6% past 12-month handgun carriage (at each wave) Mean age of initiation of carriage = 18.2 years old Temporary peak of carriage at age 15; decline during late adolescence until a steady increase in carriage at age 22 Participants carried for an average of 2.7 years Urban Black/Hispanic youth were more likely to carry during late adolescence/early adulthood and less likely to carry than White youth during adulthood Duration of carriage was associated with higher odds of violence perpetration (OR = 1.2) and selling drugs (OR = 1.2) Persistent carriers (those carrying before and after age 18) had higher likelihood of arrest than adolescent carriers (IRR = 2.6) |

Data could not distinguish between legal and illegal handgun carriage Self-report data Measures of adult drug sale and violent offending restricted to respondents reporting prior arrest; small comparison group |

6 |

| Lizotte et al. (1997) | Cohort Rochester Youth Survey administered at 6-month intervals (w1–9) then 2.5 years intervals (w 9–10) |

615 | Male youth recruited from Rochester public schools (7th/8th grade); High-crime areas (defined by arrest rates) oversampled | M Age 15 100% male 63% Black Analysis limited to male youth in the sample for w4 through w10 |

22% carried a gun at some point during any wave of the study; 6% carried a gun at w4 (age 15) 10% carried at w10 (age 20) Overall carriage rate consistent across waves Patterns of Carriage Only 1/3 of subjects carried from one wave to another, suggesting intermittent carriage among participants 53% who reported carrying only carried in one wave 21% who reported carrying carried in 2 waves 26% who reported carrying carried for ≥ 3 waves |

Self-report data Sample limited to male youth Oversampled high-crime areas, not involving suburban/rural sample |

6 |

| Loeber et al. (2004) | Cohort Developmental Trends Study with dyad (parent and their child) cohort administered at 12-month intervals for 13 years |

177 | Male children living with ≥ 1 biological parent referred from primary care clinics in either PA or GA | Ages 7–12) (baseline); followed annually to 19 30% Black 70% White 53% Urban 57% not living with biological father 41% from low SES |

20% carried a gun at least once during the study 1% reported carrying a gun at age 12 12% carried carrying a gun at age 17 Earliest age of carriage was 10 years old (< 2%) Patterns of Carriage 61% reported carrying for only 1 year 31% carried for 2-years 8% carried for 3–4 years |

Limited generalizability Small convenience sample referred from healthcare clinic Self-report data. Sample limited to male youth |

7 |

| Reid et al. (2017) | Cohort Pathways to Desistance Study, administered every 6 months for 2 years |

1170 | Convicted male youth offenders in PA and AZ (recruited from court setting). Proportion charged with drug offenses capped at 15% | Ages 14–19 M age 16 100% male 42% Black 34% Hispanic 19% White |

Among the 51% of youth who reported lifetime carriage: 57% carried during 1 period 25% during 2 periods 11% during 3 periods 6% during 4 periods 2% during all 5 periods |

Limited generalizability Sample limited to male offenders from two cities Self-report data |

6 |

| Sheley (1994) | Cross-sectional | 758 | Male students from 10 urban schools in 5 cities in CA, IL, LA, and NJ. All schools had prior firearm incidents | M age 16 Range (age 15–17) 72% Black 3% White 19% Hispanic |

12% of students carried a gun routinely (all/most of the time) with 23% reporting carriage intermittently (now/then) Youth who used and sold drugs or only sold drugs but did not use drugs were more likely to carry routinely (19% vs. 5%, p < 0.05) |

Cross-sectional data Non-representative sample of urban youth (non-random) Self-report data |

4 |

| Spano and Bolland (2011) | Cohort Mobile Youth Survey administered annually for 2 years |

1049 | Adolescents from 12 high-poverty neighborhoods in Mobile, Alabama were recruited from school, homes, community and church locations | Age 9–19 M age 13 (T1) 42% male 100% Black (2000–2001) Sample limited to those who were included in T2 and had not carried at T1 |

8% initiated gun carrying at T2 (past 90-day); Results support the nexus hypothesis (carriage occurs among a small number of gang youth at increased risk for violence behavior and exposure) over the diffusion hypothesis (gun carriage results directly from violence exposure) for initiation of gun carriage in urban youth Youth gang members who were exposed to violence at T1 were more likely to initiate gun carriage at T2 (OR = 6.5) Gang members engaged in violent behavior at T1 were more likely to initiate gun carriage at T2 (OR = 5.8) Gang members who were engaged in violent behavior and had exposure to violence at T1 were more likely to initiate gun carriage at T2 (OR = 7.7) |

High attrition rate (36%) Focused on T1 factors predicting carriage initiation (T2) Single 1-year follow-up Limited generalizability 100% Black sample Single city Sample of at-risk youth |

6 |

| Spano et al. (2012) | Cohort Mobile Youth Survey administered annually for 2 years |

1049 | Adolescents from 12 high-poverty neighborhoods in Mobile, Alabama were recruited from school, homes, community and church locations | Age 9–19 M age 13 (T1) 42% male. 100% Black (2000–2001) Sample limited to those who were included in T2 and had not carried at T1 |

8% initiated gun carrying at T2 (past 90-day); Key findings: Consistent with the stepping stone model, youth engaged in violent behavior (T1) were more likely to initiate carriage at T2 after controlling for violence exposure (AOR = 1.8) Consistent with the cumulative risk model, youth engaged in violent behavior and exposed to violence at T1 were more likely to initiate carriage at T2 compared to youth who had neither (AOR = 2.5) |

High attrition rate (36%) Focused on T1 factors predicting carriage initiation (T2) Single one-year follow-up Limited generalizability 100% Black sample Single city, Sample of at-risk youth |

6 |

| Spano and Bolland (2013) | Cohort Mobile Youth Survey administered annually for 2 years |

1049 | Adolescents from 12 high-poverty neighborhoods in Mobile, Alabama were recruited from school, homes, community and church locations | Age 9–19 M age 13 (T1) 42% male. 100% Black (2000–2001) Sample limited to those who were included in T2 & had not carried at T1 |

8% initiated gun carrying at T2. Key findings: Youth experiencing violent victimization (OR = 2.3) and violent behavior (OR = 1.9) at T1 increased the likelihood of initiating gun carriage at T2 when examined separately, but only violent victimization (OR = 2.1) was significant when both were included in the model There was no difference between the likelihood of youth who initiated gun carriage at T2 for offensive (i.e., violent behavior only at T1) versus defensive (i.e., violent victimization only at T1) purposes |

High attrition rate (36%) Focused on T1 factors predicting carriage initiation (T2) Single one-year follow-up Limited generalizability 100% Black sample Single city, Sample of at-risk youth |

7 |

| Steinman and Zimmerman (2003) | Cohort Flint Adolescent Study administered annually for 4 years during high-school (9th-12th grade) |

705 | African-American public high school students with a GPA ≤ 3.0 at risk for school dropout | M age 15 49% male 100% Black Sample limited to Black students given low base rates of gun carriage among White students Included youth who had left school |

20% of youth reported carrying a gun (80% had never carried) Patterns of carriage 15% carried episodically (during one or two waves) 5% carried persistently (during three or four waves) Compared to non-carriers, episodic carriers were more likely male (AOR = 3.6), selling drugs (AOR = 3.2), engaging with adults who carry (AOR = 1.6), engaging in fighting behaviors (AOR = 1.6) and using marijuana (AOR = 1.03) Compared to persistent carriers, episodic carriers were more likely engaging in fighting behaviors (AOR = 1.6) and selling drugs (AOR = 3.3) |

Self-report measures. Limited generalizability Sample limited to Black youth Study did not extend earlier than 9th grade so earlier risk and protective factors could not be examined |

7 |

| Vaughn et al. (2017) | Cross-Sectional Analysis uses pooled data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health | 7872 | Analysis of adolescents age 12–17 from the NSDUH national sample who reported past year gun carriage (2002–2013) | Age 12–14: 40% 15–17: 60% 83% Male 15% Black 60% White 20% low SES 78%Urban |

Latent class analysis (LCA) of handgun carrying (1 + times) adolescents identified 4-class solution: “Low-Risk” (48%): Low substance use, violence, delinquency “Alcohol/MJ users” (20%): High substance use, low levels of violence and delinquency “Fighters” (20%): High levels of violence and delinquency, but low levels of MJ and other drug use “Severe” (12%): High levels of alcohol, MJ, other drugs, violence and delinquency behaviors Socio-demographics: Compared to other classes, the low risk class was made up of more rural White youth from high SES households with fathers. Alcohol/MJ users were more likely older (15–17) Black youth from urban settings. “Fighter” class was more likely younger (12–14) Black youth from low SES homes in urban settings. “Severe” class had highest % females (males still more common), and were from urban settings. Behavioral: Compared to the low-risk group, youth in classes 2–4 were more likely to report greater risk propensity, greater parental conflict, and lower school engagement. This was most pronounced in the “severe” group. The Alcohol/MJ group and Severe group had lower levels of parental-limit setting Frequency of gun carriage: Severe subset youth were more likely to carry frequently compared to the low risk (RR 1.5), alcohol/MJ class (RR 1.5), and fighter class (RR 1.4). No difference between first 3 classes for frequency. Class 4 (severe) had higher likelihood of lifetime and past year arrest |

Cross sectional data Self-report Motivations not included |

7 |

| Watkins et al. (2008) | Cross-sectional | 967 | 338 adolescent males (age < 17) in detention; 629 adult male arrestees from Correctional Facilities in St. Louis, MO |

Adolescents M age 15 100% Male 94% Black Adults M age 31 100% Male 87% Black |

Adolescents: 46% reported carrying a gun outside of the home most/all of the time, 41% seldom carried (once per month), 13% had not carried in last year Adults: 12% carried frequently (most/all of the time), 19% seldom (once per month), 69% not at all |

Limited generalizability Small sample of juvenile arrestees from a single city Mostly Black sample Self-report measures Cross-sectional data |

6 |

Table 2.

Articles reporting data on motivations for firearm carriage among adolescent youth

| Article | Design | Sample size | Study sample and setting | Unique attributes | Carriage rates | Key findings on motivations for firearm carriage | Limitations | NOS score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ash et al.(1996) | Qualitative Semi-structured interviews |

63 | Youth offenders recruited from 5 detention centers in Atlanta, GA | Ages 13–18 M age 16 67% Male 66% Black 34% White |

Not reported | 89% of gun owners reported most important reason for carrying was “for protection” Most common location to carry was “to a club” (35%) as “that’s where my enemies are” and because I “might look at somebody wrong or they might snap on you” Respondents reported that when carrying they “felt safer” (40%); were anxious about being stopped by police (34%); energized, excited, or powerful (40%); or more dangerous (7.5% reported temptation to commit crime/saw themselves as magnet for trouble) |

Limited generalizability Nonrandom convenience sample of offenders from single city Self-report data Small sample |

6 |

| Bergstein et al. (1996) | Cross-sectional “Hands without guns” study |

1192 | 7th (n = 752) and 10th (n = 440) grade students from 12 public schools in Boston, MA and Milwaukee, WI | 49% Male | Past 30-day carriage to school = 3% Lifetime gun carriage = 17% |

Motivations for firearm carriage: Perceived safety/threats/revenge (73%) Casual handling (17%) Hunting (4%) Being cool (3%) Target practice (2%) Gang involvement (1%) |

Limited generalizability Oversampled minorities Limited to NE/MW Cross-sectional data Potential underestimate due to excluding truant youth and dropouts No socio-demographic measures beyond sex |

6 |

| Black and Hausman (2008) | Qualitative Semi-structured interviews | 23 | Youth recruited from a peer-educator violence prevention program in Philadelphia, PA | Ages 13–18 M age 16.3 61% Male |

Not reported | Protection was primary motivation for carriage, including: Protection during drug dealing Guns considered part of conducting drug deals; provided respect/symbol of wealth, power, status Protection from disrespect Among youth not involved in drug deals, guns were way to gain respect/prevent disrespect Protection from bullying Guns were seen as a means of restoring the balance of power for bullying victims Responses to gun handling Excitement/Power Initial reaction faded over time Youth excited by the gun often engaged in gunplay (flossing), which was often intermediate step between posturing and automatic behavior Fear Youth not excited by guns typically experienced fear of getting injured or getting caught Reactions to peers who carried: fear, indifference, and respect |

Limited generalizability Small sample from single urban city Self-report data Note: Study sample taken from 2001 |

7 |

| Carter et al. (2013) | Cross-sectional “Flint Youth Injury” Study | 689 | Assault-injured urban youth seeking ED treatment at a Level-1 trauma center in Flint, MI. | Ages 14–24 M age 20 50% Male 61% Black. 73% low SES |

Past 6-month carriage = 10% | Motivations for firearm ownership/carriage: Protection (37%) Holding it for someone (10%) Friends carry guns (9%) Only 17% of firearms purchased legally |

Limited generalizability Single urban ED sample Predominantly Black youth Cross-sectional data Self-report data Exclusion of suicidal and sexual assault patients may underestimate true firearm possession rates |

7 |

| Freed (2001) | Qualitative Semi-structured Interviews |

45 | Randomly selected incarcerated male youth recruited from a MD juvenile justice facility | Ages 14–18 M age 16 100% Male 67% Black 61% Urban |

Lifetime gun carriage = 60% | Reasons for not carrying a gun: Supply-side Factors Inability to find usual/trusted source (20%) Price of gun/History of gun (11%) Demand-side Factors Fear of arrest/incarceration (69%) Opinion of respected others (31%) Concern about hurting self/others (36%) No need for a gun (60%) Respondents indicated decision to carry a gun involved weighing perceived benefits (e.g., protection) against risks (e.g., getting caught, disrespecting others, hurting others/self). Half reported carrying a gun made them anxious, mainly due to fear of being caught and carrying made them “safe but in danger” |

Limited generalizability Sample limited to incarcerated male youth Qualitative study Small sample Self-report data |

6 |

| Hemenway et al. (1996) | Cross-sectional “Hands without guns” Study | 1192 | 7th (n = 752) and 10th (n = 440) grade students from 12 public schools in Boston, MA and Milwaukee, WI | 49% male | Past 30-day carriage to school = 3% Lifetime gun carriage = 17% |

Majority of respondents indicated that protection or self-defense was the reason for carrying a gun. Among those who said they carried guns, 34% reported that they were more likely to carry a gun to school if others do and only 8% were less likely (supporting the contagion hypothesis) |

Limited generalizability Oversampled minorities Geographic limitation Cross-sectional data Potential underestimate due to excluding truant youth and drop outs No socio-demographic measures beyond sex |

6 |

| Kingery et al. (1996) | Cross-sectional | 1072 | Randomly selected 8th (n = 464) and 10th (n = 608) grade middle and high school students in rural TX | 49% Male 70% White 17% Black Primarily rural population |

Past 12-month gun carriage to school = 10% | Motivations for gun carriage (to school): Angry with someone/I was thinking of shooting them (55%) It made me feel safer (48%) It showed me I could get away with breaking rules (20%) It helped me get other students to do what I wanted (19%) It made me more accepted by friends (11%) |

Limited generalizability Rural Sample Mostly White sample Only assessed carriage/motivations for carriage to school Cross-sectional data Self-report data |

4 |

| Lane et al. (2004) | Cross-sectional | 223 | Black youth living in low-SES neighborhoods (random digit dial sampling of houses) in San Francisco, CA | Ages 13–19 M age 16 42% Male 100% Black |

3-Month intention to carry = 25% (males) and 9% (females) | In males, intent to carry was associated with fear of victimization (OR 3.3) and delinquency (OR 14.2) In females, intent to carry was associated with fear of victimization (OR 4.5) and delinquency (OR 4.1) |

Limited generalizability Small, Black sample from low-income neighborhood Cross-sectional data Self-report data Proxy carriage measure |

7 |

| Mateu-Gelabert, (2002) | Qualitative Semi-structured interviews conducted as part of a longitudinal ethnographic cohort study |

25 | 7th grade students living in a New York City, NY neighborhood were followed annually for 3 years | 60% Male 100% Hispanic 84% Dominican 12% Puerto Rican 44% 1st generation immigrant 44% low SES |

Not reported | Motivations for firearm carriage (themes) Deterrence against threats/provides a sense of security in high-risk areas/situations Respect—Flashing/showing guns confers immediate respect among peers and potential attackers Self-protection and a means of proving youth are not afraid to stand up/defend oneself Necessary for illicit drug trade/protect drug markets Many report carrying because they believe others that they run into will also carry (i.e., social norms in the neighborhood) |

Limited generalizability Hispanic youth from single NYC neighborhood Qualitative study Small sample size Self-report data |

6 |

| McNabb et al. (1996) | Case control | 38 cases 103 controls |

Youth (< age 19) charged with illegal gun carriage in Jefferson Parish LA and age-, gender-, and school-matched controls recruited from public school (3:1 match) | Ages 13–18. M age 16 94% Male 46% White 43% Black |

Past 30-day carriage Case = 71% Control = 20% Lifetime carriage Case = 100% Control = 29% School carriage Case = 34% Control = 4% |

Self-defense was most common reason (40%) identified for gun carriage among both case and control subjects | Cases significantly more likely to be Black youth than gun-carrying controls Potential bias of underreported delinquency Low case response rate (54%) may misrepresent true rate of gun carriage Self-report data |

7 |

| Sheley (1993) | Cross-sectional | 835 | Male inmates recruited from 6 correctional facilities in CA, NJ, IL, LA. | Age 12–21 M age 17 100% Male 46% Black 29% Hispanic > 50% Urban |

Lifetime carriage = 55% (routinely) | Reasons for gun carriage (during a crime): Defense/Ready to defend self (80%) Chance victim would be armed (58%) Need a weapon to escape crime scene (49%) Victim won’t put up a fight (45%) People don’t mess with armed person (42%) Circumstances most likely to carry a gun: During a drug deal (50%); Raising hell (32%) In a strange area (72%); At night (58%) Hanging with friends (38%); Friends were carrying (39%); Needing protection (75%); Planning to do a crime (37%) Based on above results, no support for status hypothesis; Most circumstances involved needing gun for protection |

Limited generalizability Incarcerated youth sample Cross-sectional data. Self-report data |

4 |

| Wilkinson and Fagan (1996) | Qualitative | 30 | Subsample of larger qualitative study of Inner-city adolescent males recently released from Rikers Island Prison between 4/1995–5/1996 | Ages 16–24 100% Male |

Not reported | Carrying a firearm provided sense of personal safety All respondents reported that carrying guns was necessary for self-defense or protection of themselves, peers, family members, or girls. Underlying reasons for need for protection varied, including both general and specific deterrence reasons. Respondents endorsing need for “protection” also noted that this was often followed by violent conflict or victimization |

Limited generalizability Small qualitative sample Subsample of larger study Self-report data |

4 |

| Wilkinson et al. (2009) | Qualitative Semi-structured Interviews |

416 | Violent offenders from two NYC neighborhoods with history of: (1) conviction for illegal gun possession/violent offence; (2) violent injury requiring hospital care; or (3) recent violence involvement |

Age 14–27 M age 20 100% Male 49% Black 40% Hispanic |

80% carried a firearm at least some of the time Perceived peer carriage = 79% 21% youth perceive that their peers carry guns everyday |

50% reported that protection was the main reason for carrying Emerging qualitative themes included that peer pressure to carry guns was primarily around the need to carry for safety/protecting peer group (e.g., pre-emptively address threats of violence), to retaliate for prior altercation, or to provide safety after a violent event. Less common to carry a weapon for status symbol, social recognition/reputation. Perceived reasons for peer gun carriage: For protection (65%) Involvement in drug trade (30%) Carry to avoid beefs (21%) Carry b/c it is cool (6%) Carry b/c they have to (2%) Carry gun to have it (1%) Carry to kill/claim turf (2%) Perceived peer carriage = 79% |

Limited generalizability Violent offender sample Single urban setting Qualitative Interviews Self-report data Note: Original Interviews conducted 9/1995–7/1998 |

4 |

Table 3.

Articles reporting data on risk and protective factors for adolescent firearm carriage

| Article | Design | Sample size | Study sample and setting | Unique attributes | Carriage rates | Results | Limitations | NOS score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allen and Lo (2012) | Cross-sectional Secondary analysis of data from Sheley(1994) Study |

835 juvenile inmates 695 students |

Male inmates from 6 correctional facilities and 9th-12th grade students from 10 inner-city public high schools in CA, LA, IL, and NJ | Ages 15–19 100% male Students: M age 17 73% Black 18% Hispanic Inmates: M age = 17 46% Black 29% Hispanic |

Rates of co-occurring drug trafficking and gun carriage: Students = 16% Inmates = 65% |

Students: After controlling for age, absentee father, employment, h/o expulsion (OR 2.6), and code-based beliefs (OR 1.2) were positively associated with co-occurring drug dealing and gun carriage. Negative associations were Non-black (OR 0.10) and Hispanic (OR 0.47) race/ethnicity Inmates: After controlling for age/employment, having an absentee father (OR 3.7), h/o violent behavior (OR 4.4), and code-based beliefs (OR 1.2) were positively associated with drug dealing/gun carriage. Negative associations were non-black (OR 0.1) and Hispanic (OR 0.2) race/ethnicity |

Limited generalizability All-male student and inmate samples from select cities in four states Cross-sectional data Self-report data Questionnaires were not identical for samples. Note: study sample is from 1991 (published 2012) |

6 |

| Apel and Burrow (2011) | Cohort 2 waves of data from National Longitudinal Youth Survey |

1524 | Nationally representative sample of US youth with oversampling of Black/Hispanic youth | M age 13 (w1) 52% male 15% Black 12% Hispanic |

Lifetime carriage = 7.4% in w1 Past 1-year carriage = 5.8% in wave 2 |

In cross-sectional model (independent/dependent variables from 1997 data; exposure to violence (i.e., gunshots in neighborhood) was correlated with carriage (OR 2.3), bullying was not correlated after adjusting for demographic, family, school, peer affiliation, and other factors. In longitudinal model (independent variables 1997; dependent variables 1998), exposure to violence was correlated with carriage (OR 2.0), but bullying was not correlated after adjustment | Self-report data Limited to young adolescent sample Note: study sample taken from 1997 (published 2011) |

6 |

| Arria et al. (1995) | Cohort Surveyed annually for 5 years |

1714 | Students from 43 classrooms within 19 public schools from 5 districts in MD | M age (w1) 9 M age (w5) 13 50% Male 73% Black 26% White |

Past 1-year carriage = 10% (Male) 1% (Female) |

Rates of gun carriage increased across waves of data, starting at < 2% (w1) and increasing to 10% (male) and 1%(female) by w5 data collection; Less lethal weapon carriage (stick, knife) was associated with gun carrying at later waves across multiple waves | Limited generalizability Single city; Younger Adolescent sample Missed student drop-outs Self-report data |

6 |

| Beardslee, et al. (2018a) | Cohort Pittsburgh Youth Study; Data is from 6-month surveys (3 years) and then 12-month surveys in ages 10–17 |

485 | Random sub-sample of male youth from youngest cohort of large school-based longitudinal study in Pittsburgh, PA | 100% male 56% Black 41% White Excluded non-White/Black participants |

Lifetime gun carriage = 27% (Black) 12% (White) |

Youth with higher levels of conduct problems and peer delinquency at earlier childhood waves, as well as those with increases in conduct problems across early childhood waves, were more likely to initiate gun carriage before 18 Examining whether racial differences in carrying behavior were due to differential exposure to risk factors or differential sensitivity, study found more support for differential exposure model, with 60% of the race effect on carriage being attributable to either initial peer delinquency levels or initial levels of conduct problems |

Limited generalizability Limited to male Black/White youth sample Single city sample Self-report data. Small sample size may limit ability to detect group differences in predictors of carriage |

6 |

| Beardslee et al. (2018b) | Cohort Pathway to Desistance Study: Data collected every 6-month for 3 years then every 12-month for 4 years |

1170 | Male offenders recruited from court system in two counties in AZ (Maricopa) and PA (Philadelphia) | Ages 14—19 at baseline 100% male 42% Black 34% Hispanic 19% White 70% on active probation at baseline |

Past 6-month Carriage = 15%(w1); 15%(w3); 12%(w5); 12%(w6) Past 12-month carriage 17% (w7); 10% (w10) |

Among youth with recent offending, gun violence exposure (witness/victim of gun violence) were 43% more likely to engage in carriage at the next wave after controlling for time-stable and time-varying (exposure to peers who carried; exposure to peers engaged in other criminal acts, developmental changes, changes in gun carrying from incarceration or institutionalization) covariates No evidence that non-gun violence exposure conferred same risk |

Limited generalizability Male sample of juvenile offenders in two states Self-report data Youth offenders likely had fluctuations in carrying over time |

6 |

| Cao et al. (2008) | Cross-sectional Nat. Crime Victim. Survey (School Crime Supp. data) |

7391 | Youth in public or private school. Limited to Black and White (Hispanic and non-Hispanic) youth. Nat. representative sample | Ages 12–17 M age 15 52% male 70% White 16% Hispanic 14% Black 91% public school |

Past 6-month carriage to school = 0.5% | Among adolescents attending public/private school, those carrying a gun for protection were more likely to report recent involvement in physical fighting (AOR 1.1); knowing a peer carrying guns (AOR 2.0), and not being female (AOR = 0.8). Factors not significant in the model included fear of being attacked, avoidance, substance use factors, gangs at school, truancy, security guards, age, race, parental education, rurality, and region | Limited generalizability Low incidence of carriage Limited ethnic/racial groups Cross-sectional data Excluded carriage-related factors (e.g., sell drugs) Fighting may have been aggression or victimization |

6 |

| Carter (2013) | Cross-sectional Flint Youth Injury Study |

689 | Assault-injured urban youth seeking ED treatment at a Level-1 trauma center in Flint, MI | Ages 14–24 M age 20 50% Male 61% Black. 73% low SES |

Past 6-month carriage = 10% | Male gender (AOR 2.8), higher SES status (AOR 1.5), ilicit drug use (AOR 1.6), serious physical fighting (AOR 1.7), and attitudes favoring retaliatory violence (AOR 1.6) were associated with firearm possession. Age and race were not significant predictors of possession (carriage/ownership) | Limited generalizability Single urban ED sample Predominantly Black youth Cross-sectional data Self-report data Exclusions may lead to underestimation of carriage |

7 |

| Connolly and Beaver (2015) | Cohort National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, surveyed annually for 8 years |

1304 sibling pairs | Sibling pairs nested within the nationally representative sample of youth; oversampled Black/Hispanic adolescents | Ages 12–18 at start of study; 27 monozygotic (MZ) twins, 932 dizygotic (DZ) twin/full sibling pairs, 75 half-sibling (HS) pairs | Lifetime carriage = 9.6% (among the full sibling sample) 5% (MZ) 10% (DZ) 13% (HS) |

Half-siblings reported higher rates of gun carrying than MZ twins, DZ twins, or full siblings. Within-sibling concordance was higher for MZ twins (p < 0.05) than for DZ twins/full siblings (p < 0.05), and half-siblings (p < 0.05). Additive genetic effects explained 27% of variation in gun carriage. Common genetic influences explained 66% of covariance between gun carrying and gang membership. Shared environmental factors didn’t explain variance across models, with non-shared environmental factors explaining remainder of variance not accounted for by genetic factors | Limited generalizability Sample of sibling pairs may not represent non-siblings Self-report data Note study sample taken from 1997 to 2005 (published 2015) |

6 |

| Cook and Ludwig (2004) | Cross-sectional 1995 National Survey of Adolescent Males (NSAM) |

1151 | Male youth living in US households. Survey was of youth 15–19, but analytic sample restricted to under age 18 | Ages 15–17 100% male 38% White 28% Black 31% Hispanic 46% Urban 34% Suburban 20% Rural |

Past 30-day carriage = 10% | Likelihood of gun carriage among youth was positively associated with rate of robbery (AOR 6.0) and prevalence of gun ownership (AOR 4.9) after controlling for individual and household characteristics Of note, Black and Hispanic youth were more likely to carry guns than others, although for Hispanics-effect was limited to those in English-speaking homes. Gun carriage was not associated with age, grade, or household SES status |

Cross-sectional data. Self-report data Used proxy variable (FS/S, suicides committed with guns) for measure of gun availability |

7 |

| Cunningham et al. (2010) | Cross-sectional | 2069 | Consecutive sample of adolescents (age 14–18) presenting for any reason for ED treatment at a Level-1 trauma center in Flint, MI | Ages 14–18. 45% Male 57% Black 53% low SES 40% seeking ED treatment for an injury |

Past year carriage = 7% | Gun carriage was associated with Black race (OR 2.4), Male sex (OR 2.4), failing grades (OR 1.5), Marijuana use (OR = 3.3), recent gun victimization (OR 1.9), recent physical fighting (OR = 1.6), group fighting (OR = 3.3), sexual activity (OR = 2.4). Gun carriage frequency was associated with older age (IRR = 1.3), male sex (IRR = 1.3), failing grades (IRR = 1.6), employed (IRR = 1.4), lower SES (IRR = 1.8), binge drinking (IRR = 1.3), fighting resulting in injury (IRR = 1.8), recent gun victimization (IRR = 1.2), serious fighting (IRR = 1.3), and group fighting (IRR = 1.6) | Limited generalizability Urban mostly Black sample Cross-sectional data Self-report data Exclusion of suicidal and sexual assault patients may underestimate gun carriage |

7 |

| DuRant et al. (1999) | Cross-sectional | 2227 | Randomly selected 6–8th grade students attending 53 randomly selected public middle schools in NC | Ages 11–16 36% age 13 51% male 64% White 28% Black 2% Hispanic |

Ever carried to school = 3% | RF for carriage included Male sex (AOR 7.1), Minority ethnicity (AOR 3.3), Alcohol use (AOR 4.6), Cocaine use (AOR 3.0), Marijuana use (AOR 3.7), and Smoking frequency (AOR 1.3). Having ever carried a gun, having been threatened with weapon/in a fight, and suicidality were not predictive. Those who smoked daily were 8 times as likely to carry. Controlling for age/sex, earlier age of onset for substance use (i.e., cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use) was associated with carriage to school | Cross-sectional data Self-report data Sampling design doesn’t account for potential for clustering of behaviors within schools |

7 |

| Freed et al. (2001) | Qualitative semi-structured Interviews | 45 | Male youth incarcerated in a MD juvenile justice facility | Ages 14–18 M age 16 100% Male. 67% Black 61% Urban |

Lifetime gun carriage = 60% | Bivariate comparisons found that those who owned or carried a gun were more likely to be have sold drugs (89% vs 56%, p = 0.05), been victimized by someone with a weapon (81% vs 33%, p < 0.01), and to have lived in city (71% vs 39%, p< 0.05) | Limited generalizability Incarcerated male youth Qualitative study Small sample Self-report data |

6 |

| Hayes and Hemenway (1999) | Cross-sectional Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) in MA | 3153 | Random sample of 9–11th graders from MA public schools | Age 15–18 50% Male 71% White 9% Black 8% Hispanic 50% Urban 14% Rural |

Past 30-day carriage = 5% | Risk factors associated with past 30-day gun carriage included: male gender (OR 5.0), Black race (OR 2.5), older age within class (OR 2.1), gang membership (OR 7.2), missing school out of concern for safety (OR 2.5), seeking medical treatment after a fight (OR 4.5), and fighting without seeking medical treatment (OR 5.7) | Cross-sectional data Self-report data Misses students not in school Excluded large % of original sample (entire 12th grade) |

7 |

| Hemenway et al. (1996) | Cross-sectional “Hands without guns” study |

1192 | 7th (n = 752) and 10th (n = 440) graders from 12 public schools in Boston, MA and Milwaukee, WI | 49% male | Past 30-day carriage to school = 3% Lifetime carriage = 17% |

RFs associated with higher likelihood of concealed gun carriage included male sex (OR 5.1), older age/grade (OR 2.1), smoking (OR 5.5), alcohol use/binge drinking (OR 1.8), poor academic performance (OR 1.7), lack of self-efficacy to avoid fighting (OR 2.7), family member victim of shooting (OR 2.3), neighborhood with a lot of shootings (OR 2.9), and no serious discussion with parents about guns (OR 1.5) | Limited generalizability Oversampled minorities Limited to NE/MW Cross-sectional data. Potential underestimate due to excluding truant/dropouts No socio-demographic measures beyond sex |

6 |

| Hemenway et al. (2011) | Cross-sectional Biennial Boston Youth Survey |

1737 | 9th-12th grade students in Boston, MA recruited from 22 public high schools; Analytic sample restricted to those who answered questions on gun carriage | 28% 10th grade 46% male. 41% Black 32% Hispanic 9% White |

Past 12-month carriage = 5% | Risk factors for carriage included male sex (OR 2.8), alcohol, tobacco, or drug use in past month (OR 2.4), lack of an adult who encouraged them (OR 2.7), having witnessed violence in past month (OR 2.3), recent peer victimization (OR 3.5), gang membership (OR 4.7), and gun access (OR 2.0). In addition, living in neighborhoods where gun carriage rates high (> 8%) predicted carriage (OR 2.2), as did youth overestimates of peers carrying (OR 2.5). On average, youth estimated that peer carriage in their neighborhood was 33% with mean estimates higher than “actual” levels in every neighborhood tested. Among youth who overestimated rates of peer carriage, 69% reported that they would be less likely to carry themselves | Limited generalizability Mainly minority youth sample Mainly urban high schools Cross sectional data Self-report data No information on non-responders (7%) or those not in school (31%)—potential for underestimate of actual level of gun carriage. |

6 |

| Kingery et al. (1996) | Cross-sectional | 1072 | Randomly selected 8th (n = 464) and 10th (n = 608) grade middle and high school students in rural TX | 49% Male 70% White 17% Black Primarily rural population |

Past 12-month gun carriage to school = 10% | Discriminant analysis found 18 factors related to past year carriage, including exposure to unsafe neighborhoods, cocaine use (lifetime), recent physical fighting, riding on empty buses/trains, belief that carrying is effective to avoid fighting, earlier initiation of cocaine use, being victimized while on the school bus, going outside to sell items door-to-door alone, being threatened but not hurt in past year (outside of school), victim of forced sex, male sex, higher frequency crack use, attitudes favoring gang membership as means of avoiding fighting, higher grade, having possessions stolen by force/threat of force, less instruction in school on means of avoiding fighting/violence, White race, being threatened (but not hurt in past year) at school | Limited generalizability Rural Sample Predominantly White sample Only assessed carriage and motivations for carriage to school Cross-sectional data Self-report data |

4 |

| Lane et al. (2004) | Cross-sectional | 223 | Black youth living in low-SES neighborhoods (random digit dial sampling of houses) in San Francisco, CA | Ages 13–19 M age 16 42% Male 100% Black |

3-month intention to carry = 25% (males) and 9% (females) | In males, intent to carry was associated with fear of victimization (OR 3.3) and delinquency (OR 14.2). In females, intent to carry was associated with fear of victimization (OR 4.5) and delinquency (OR 4.1) |

Limited generalizability Small, Black youth sample from low-income neighborhood Cross-sectional data Self-report data Intention to carry gun was proxy measure for carriage |

7 |

| Lizotte et al. (2000) | Cohort Rochester Youth Survey given at 6-month intervals (w 1–9) then 2.5 year intervals (w 9–10) |

617 | Male Youth recruited from Rochester public schools (7th/8th grade); Oversampled high-crime areas (defined by arrest rates) |

100% Male M age 14 (w2) M age 20 (w10) 63% Black 20% White 18% Hispanic Analysis limited to male youth remaining at w10 |

Past 6-month carriage = 5–6% (w2) and 8–10% in w9–10. | Those who carried guns had much higher rate of serious assaults and armed robberies (mean 0.8, p< 0.01). In early adolescence, gang membership is a strong predictor of illegal gun carriage (OR between 3.6 and 8.0 in w2–4). In older adolescence, selling drugs, especially high levels of drugs (OR between 8.0 and 34.7 in w5–10) and illegal peer gun ownership (OR between 2.4 and 23.8 in w5–10) replace gang membership as the primary determinants of illegal gun carriage. Drug use, particularly high drug use, is a significant predictor of carriage at almost every wave. Delinquent values has a sporadic impact on carriage with most of the effect occurring at mid-adolescence. Finally, carriage at a prior wave is a predictor (OR between 3.3 and 8.9) of carriage at nearly every wave (except w7 & 8) | Self-reported data Sample limited to male youth Oversampled high-crime areas of Rochester, not a suburban or rural sample |

6 |

| Loeber et al. (2004) | Cohort Develop-mental Trends Study with dyads at 12-month intervals for 13 years | 177 | Male children living with ≥ 1 biological parent referred from primary care clinic in either PA or GA | Ages 7–12 (baseline); followed to 19 30% Black 70% White 53% urban 57% not living with bio-father 41% low SES |

Lifetime carriage = 20% 1% carriage (age 12) 12% carriage (age 17) |

Gun carriage significantly associated with older age youth (IRR 1.7), violent behavior (IRR 1.1), conduct disorder (IRR 5.2), and maternal psychopathy (IRR 1.1). Youth were less likely to carry firearms if they had been victimized (IRR 0.8). Protective factors included parental monitoring (IRR 1.1). Race/ethnicity, SES, rurality, and anxiety disorder were significant in bivariate model but were not included in the multivariate model | Limited generalizability Small, convenience sample referred from a healthcare clinic Self-report data Sample limited to male youth |

7 |

| Luster and Oh (2001) | Cross-sectional 1997 National Longitudinal Youth Survey (NLYS97) | 4619 | Representative sample of U.S. male youth from the NLYS97 survey Analytic sample limited to males Separate analysis for those < 15; and those ≥ 15 | Age 12–16 100% male 50% White, 25% Black, 21% Hispanic 57% Urban 43% Rural M Income = 47 K |

Past 1-year carriage = 9% Lifetime = 16% <15: past 1-year carriage = 8% ≥ 15 past 1-year carriage = 11% |

Predictors of handgun carrying: Under age 15: White youth (OR 2.9), Problem Behaviors (OR 1.5), witnessed shooting before age 12 (OR 2.1), Relatives of friends in a gang (OR 1.7), gang membership (OR 3.0), hearing gunshots in their neighborhood (OR 1.2). Protective factors included parental monitoring (OR 0.9) and high-levels of maternal respect (OR 0.9) Over age 15: Problem Behaviors (OR 1.5), witnessed shooting before age 12 (OR 2.4), negative peer influence (1.3), and gang involvement (OR 3.2) |

Limited generalizability Oversampled Black and Hispanic youth Cross-sectional data Self-report data Excluded those who carried a gun previously but not within the past 12-months |

6 |

| May (1999) | Cross-sectional | 8338 | High school students from urban and rural counties in MS selected via two-stage process (urban, non-urban) | Ages 13–20. 45% Male 53% Black 47% White |

Lifetime carriage to school = 8% | Factors associated with gun carriage to school included male sex (OR 4.4), Black race (OR 1.6), older age (OR 1.7), higher household income (OR 1.1), gang membership (OR 5.3), perceived neighborhood incivility (OR 1.1), and higher fear index (OR 1.1). Gun carrying to school was less likely in those from two-parent homes (OR 0.8) and with higher social control index scores (OR 0.9) | Limited generalizability Majority Black sample from MS Non-random selection Cross-sectional data Self-report data Note: study sample taken from 1992 (published 1999) |

5 |

| McNabb et al. (1996) | Case control | 38 cases; 103 controls | Youth (< age 19) charged with illegal gun carriage in Jefferson Parish LA & age-, gender- and school-matched controls recruited from public school (3:1 match) | Ages 13–18 M age 16 94% Male 46% White 43% Black |

Past 30-day carriage Cases = 71% Controls = 20% Lifetime carriage Cases = 100% Controls = 29% School carriage Cases = 34% Controls = 4% |

Risk factors for firearm carriage included reporting that the school was not safe (AOR 9.0), seen a shooting (AOR 7.0), marijuana use (OR 6.8), and a history of firing a gun (OR 17) Risk factors for being charged with firearm carriage included the lack of a employed male in households with male parents (AOR = 8.6), marijuana use (AOR = 11.7), and watching TV for more than 6 h/day (AOR 6.5) |

Cases significantly more likely to be Black youth than gun-carrying controls Potential bias of underreported delinquency Low case response rate (54%) may misrepresent true rate of gun carriage Self-report data |

7 |

| Molnar et al. (2004) | Cross-sectional Project Human Development |

1842 | Population-based sample of age 9–19-year-old youth from 218 neighborhoods in Chicago, IL | Ages 9–19 36% age 9–12 36% age 13–15 29% age 16–19 50% male 30% Black 42% Hispanic 14% White 25% low SES |

Lifetime carriage = 3% (4.9% boys, 1.1% girls) | After controlling for individual/family factors, neighborhood factors significant in separately tested models included lack of neighborhood safety (OR 5.8), neighborhood social disorder (OR 1.9), and neighborhood physical disorder (OR 2.3). Neighborhood protective factors included collective efficacy (OR 0.3). Significant individual/family factors influencing gun carriage differed by model, but included male gender, older age, presence of guns at home, prior family member shot with gun, witnessed prior violence, and prior victimization by violence. Note, 76% of those who carried a gun had a family member shot by gun. Most gun carriers (63%) were in highest quartile on scale of delinquent & aggressive behaviors (p < 0.05) | Limited generalizability Single urban sample with large Hispanic population Cross-sectional data Self-report data |

7 |

| Orpinas et al. (1999) | Cross-sectional Students for Peace Study |

8865 | 6th-8th graders from 8 urban middle schools in a large TX school district | M age 13 66% Hispanic 19% Black 8% White 4% Asian |

Past 30-day carriage = 10% | Students with low parental monitoring were significantly more likely to carry a handgun than those who had very high monitoring (Boys OR 19.8, Girls OR 26.3). Students who got along “very bad” with their parents were more likely to carry a handgun than those who get along “very well” (Boys OR 7.9, Girls OR 22.7). No multivariate model predicting gun carriage (only weapon carriage) | Limited generalizability Single urban school district Mainly Hispanic sample Cross-sectional data Self-report data Missed students not in school |

7 |

| Peleg-Oren et al. (2009) | Cross-sectional FL Youth Substance Abuse Survey (FYSAS) & FL YRBS |

12,352 | Randomly selected 11th and 12th grade students from FL schools. FYSAS data collected 2006 (N = 10,626) and YRBS in 2005 (N = 1726) |

YRBS 54% Female 57% 11th grade 50% White 24% Hispanic FYSAS 54% Female 58% 11th grade 61% White 14% Hispanic |

YRBS: Past 30-day carriage to school = 5% FYSAS Past 1-year = 5% (outside school) Past 1-year = 1% (in school) |

YRBS: After controlling for socio-demographic factors (sex, race, grades), very early drinkers (vs. early drinkers) [AOR = 3.1] and very early drinkers (vs. non-drinkers) [AOR = 29.4] were predictive of gun carriage. FYSAS: After controlling for socio-demographic factors (sex, race, grades), very early drinkers (vs. early drinkers) [AOR = 2.5] and very early drinkers (vs. non-drinkers) [AOR = 5.6] were predictive of gun carriage and also gun carriage to school (AOR of 2.6 and 5.1, respectively) |

Cross-sectional data. Self-report data. Adjusted only for socio-demographic factors |

6 |

| Reid et al. (2017) | Cohort Pathways to Desistance Study, given every 6 months for 2 years |

1170 | Convicted male youth offenders in PA and AZ (recruited from court). Proportion charged with drug-related offenses capped at 15% | Ages 14–19, M age 16 100% male 42% Black 34% Hispanic 19% White |

Lifetime carriage at beginning of study = 51% | After controlling for study site, race/ethnicity, age, and proportion of time on the streets, global severity index score (i.e., psychological distress measures) was predictive of gun carriage at 3 of 4 time points (12, 18, 24-months) with OR ranging from 1.4 to 2.3 After adding exposure to violence (witnessed and experienced) to the model, the global severity index was no longer a significant predictor of gun carrying. However, exposure to violence remains significant at every wave with increasing odds ratios ranging from 1.4 to 1.6 |

Limited generalizability Sample limited to male juvenile offenders from two cities Self-report data |

6 |

| Ruggles and Rajan (2014) | Cross-sectional CDC Youth Risk Behavioral Survey (YRBSS) |

88,608 (Six waves of data) |

9th-11th grade students drawn from randomized sample of US high schools. Analytic window is YRBSS data from 2001 to 2011 | Not reported | Past 30-days 5.7% (2001) 6.1% (2003) 5.4% (2005) 5.2% (2007) 5.9% (2009) 5.1% (2011) |

43 out of 54 risk behaviors included in the YRBSS were associated with carriage, including strongest associations with alcohol, tobacco, and drug use overall and at school. Gun carriage was also strongly associated with feeling unsafe and being threatened at school. Finally, carriage also had associations with being the victim of sexual assault, to be engaged in disordered eating behaviors, to not wear sunscreen regularly, to have riden in a car with a drunk driver, and mental health factors (e.g., suicidality) | Cross-sectional data Self-report data Limitations associated with hierarchical clustering methodology Behaviors could be proxies for broader social issues |

7 |

| Sheley (1994) | Cross-sectional | 758 | Male students from urban schools in 5 cities in CA, IL, LA, and NJ. All schools had prior gun incidents | M age 16 Range (age 15–17) 72% Black 3% White 19% Hispanic |

12% carried routinely (all/most time) 23% carried now/then |

Youth who used and sold drugs or only sold drugs but did not use drugs were more likely to report carrying a gun routinely (19% vs. 5%, p < 0.05) Those who endorsed heavy drug use had higher rates of gun carriage (72 vs 10%, p < 0.05). |

Cross-sectional data Not a representative sample of urban youth (non-random recruitment) Self-report data |

4 |

| Sheley and Brewer (1995) | Cross-sectional | 418 | 10 and 11th grade students at 3 of 7 suburban public high schools in Jefferson Parish LA | M age 16 48% male 66% White, 21% Black |

Current carriage = 17% | Gun carriage was associated with male sex (AOR = 1.1), White race (AOR = 1.4), drug activity (AOR = 1.2), and violent criminality (AOR = 1.7). Dangerous environmental exposure is significant overall (i.e., threatened with gun). Environmental findings differend by sex, with having been threatened with gun significant for boys, while fear of being shot by age 25 was significant for girls | Limited generalizability Suburban sample Cross-sectional data Self-report data |

6 |

| Simon et al. (1998) | Cohort | 2200 | 9th and 12th grade students from 6 school districts in San Diego and Los Angeles, CA. Analytic sample is 12th grade students with complete data |

44% Male 30% White 38% Hispanic 8% Black 11% Asian 32% low SES |

Lifetime gun carriage Boys = 22% Girls = 5% |

Psychosocial: Risk-taking (male = AOR 3.1; female = AOR 4.1), depression (male = AOR 1.6; female = AOR 2.4), stress (male = AOR 1.9; female = AOR 2.8), and temper (male = AOR 1.9; female = AOR 2.8) in 9th grade was predictive of carriage in 12th grade for male and female students Behavioral: 9th grade factors including 3 + days school absence (AOR 2.4), 2 + parties in prior month (AOR 1.9), cigarette (AOR = 2.2), alcohol (AOR = 1.9), and MJ (AOR 2.3) use were predictive of carriage in 12th grade for males. For females, cigarette (AOR 5.1), alcohol (AOR 3.7), and MJ (AOR 3.6) use in 9th grade predicted 12th grade carriage Perceptions neighborhood crime and SES were associated w/carriage after adjusting for demographics (age, gender) |

Limited generalizability Geographic distribution Self-report data Only included students completing survey at both timepoints (may miss school dropouts who may be more likely to carry guns) |

7 |

| Tigri et al. (2016) | Cohort National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, data from 5 yrs of annual surveys | 5018 | Nationally representative sample of youth throughout the US. Analysis excludes NLSY oversample of Black and Hispanic youth | M age 14 at baseline; M age 19 at last wave 50% male 70% White |

Lifetime carriage = 9% at baseline Past 1-year carriage = 4% at final wave |

After adjusting for age, race, sex, prior carriage, prior peer gang membership, prior gang membership, prior delinquency, current gang membership (OR ranging 2.5–4.2), current peer gang membership (OR ranging 1.6 to 2.2), and delinquency behaviors OR ranging 1.8–2.8) were associated with carriage. Gang membership was strongest RF; delinquency measure most consistent. When examined by sex, gang membership is stronger for both sexes in early adolescence and diminishes in late adolescence (esp for females). Association of gang membership with carriage was inconsistent across race/ethnicity | Self-report data No characterization of gun carrying frequency No temporal causality given that RF were examined concurrently at time points (although accounted for lagged RF from prior waves of data) |

5 |

| Turner et al. (2016) | Cohort National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, Sample drawn from 14 years of annual data | 6641 | Nationally representative sample of youth throughout the US. Analysis excludes NLSY oversample of Black and Hispanic youth. | M age 14 at start of study, M age 27 at end of study. 51% Male 70% White 16% Black 14% Hispanic |

Lifetime carriage = 28% Past 1-year carriage = 24% Past 30-day carriage = 13% Past 30-day carriage to school = 1% |

Repeat bullying victims were more likely (than non-victims) to carry during past 1-year (OR 1.3) and 30-days (OR 1.2) after controlling for prior carriage and socio-demographic factors, peer gang membership, neighborhood gang presence, gang membership. When examined by age, only childhood bullying victims remained significantly associated with carriage; adolescent victims and victims during childhood & adolescence were not associated with carriage. Repeat bullying and childhood repeat bullying predicted gun carriage in propensity score matching analysis | Self-report data Recall bias from retrospective measure of bullying Unclear cross-over effect (i.e., proportion of bullying victims were also aggressors) |

6 |

| Vaughn et al. (2012) | Cross-sectional 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) |

17,842 | Multistage probability sample weighted to create a nationally representative sample of US youth (age > 12); Sample restricted to age 12–17 y/o | Mean age 15 51% Male 59% White 18% Hispanic 14% Black 16% low SES |

Past year carriage = 3% | Factors associated with carriage included male sex (AOR 4.5), prior incarceration (AOR 3.8), selling drugs (OR 16.1), stealing > $50 (AOR 7.5), aggression (AOR 7.0), serious fighting at school (AOR 3.8), ecstasy (OR 5.3), hallucinogen (AOR 4.1), cocaine/crack (AOR 7.7), MJ (AOR 4.1), or heroin (AOR 5.3) use, danger seeking (AOR 4.4), and risk taking behavior (AOR 4.7). Across a range of parental involvement and monitoring behaviors, all were significantly associated with lower likelihood of carrying a gun. Youth who were exposed to violence prevention and drug prevention programming/messaging outside of school were associated with lower likelihood of gun carriage | Cross-sectional data Self-report data |

7 |

| Vaughn et al. (2016) | Cross-sectional National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) |

197,313 | Multistage probability sample weighted to create a nationally representative sample of US youth (age > 12); Sample restricted to age 12–17 y/o | Ages 12–17 51% male 66% White 15% Black 19% Hispanic |

Past year carriage = 3% | Carriage is examined by race/ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic). Across all groups, male gender and history of violence/delinquency (i.e., fighting at school/work, violent aggression, selling drugs, stole > $50) were associated with carriage. Black youth with household income < $20 K were more likely to carry (OR 2.2). Hispanic youth engaged in binge drinking were more likely to carry (OR 1.8). Marijuana use (OR 1.5) and having substance using friends (OR 1.3) increased likelihood of carriage in Black youth. High parental affirmation protected against carriage for White (OR 0.7) and Hispanic (OR 0.6) youth, while parental control was protective for White (OR 0.9) youth only | Self-report data Cross-sectional data May have missed adolescents most likely to carry a gun (i.e., not in school) Does not investigate specific contextual factors that relate to gun carrying |

7 |

| Watkins et al. (2008) | Cross-sectional | 967 | 338 males in juvenile detention (< age 17); 629 incarcerated adult male; Recruited from St. Louis, MO Correctional Facilities | Adolescents M age 15 100% Male 94% Black Adults M age 31 100% Male 87% Black |

Past 12-month carriage 46% most/all of time 41% seldom | Among subsample of juvenile males in detention who also endorsed gun possession (N = 202), factors predicting an increased frequency of gun carriage included age, black race, and gang membership. Among perceptual factors, you who perceived an increase in the prevalence of guns over the past year were less likely to report gun carriage Deterrent measures, such as perceptions about gun use penalties and increased risk of arrest were not significant and appeared to have no effect on gun carriage |

Limited generalizability Small sample of juvenile arrestees from single city Mostly Black sample Cross-sectional data Self-report |

6 |

| Webster et al. (1993) | Cross-sectional | 294 | 7th and 8th grade students at two inner-city public high schools in low SES/high-crime areas of Washington, D.C. | Ages 11–16 M age 14 (School A) M age 13 (school B) 100% Black |

Past 2 wk carriage = 16% (carriers) Lifetime carriage Males = 23% (A) Males = 40% (B) Females = 4%(A) Females = 5% (B) |

Factors predicting gun carriage (for protection or use in a fight) among male youth included prior arrest (OR 16.1), knowing more victims of violence (OR 1.1), history of initiating fights (OR 51.5), perceptions about peer acceptability of violence behaviors (norms) (OR 1.2), and more willingness to endorse views that there are justifiable reasons to shoot someone (OR 1.6). Of note, all males who had a history of arrest for drug-related charges reported carrying a firearm in the sample | Limited generalizability Small geographic Distribution Analysis restricted to male and Black youth Cross-sectional data Self-report data Convenience sample |

4 |

| Wilcox et al. (2006) | Cohort Rural Substance Abuse and Violence Project (RSVP) |

3968 | 7th-9th grade students from 113 public middle/high schools in KY followed annually for 4 years (2001–2004) | 48% Male 89% White Analysis restricted to first three waves of data |

Past yr school gun carriage reported as ordinal scale (1–5) with 1 = never; 5 = daily W1 M = 1.04 W2 M = 1.04 |

Using SEM, authors found support for the “triggering” over the “fear and victimization” hypothesis around carriage. They found that the frequency of carriage in 8th grade was positively associated with 9th grade fear, risk perception, victimization, and offending (supporting the triggering hypothesis). Authors also found that fear and victimization in 7th grade was not related to carriage in 8th grade (non-significant) and that 7th grade risk perception was negatively related to carriage (contradicting the fear and victimization hypothesis). Further, previous carriage and gun ownership were strong predictors related to gun carriage. | Limited generalizability KY sample Sample size limited by need for parental consent (low response rate, potentially biasing sample) Self-report data Large number of missing data cases |

5 |

| Williams et al. (2002) | Cross-sectional | 21,981 | Representative sample of 6th, 8th, and 10th grade public school students across 27 IL communities (ages 10–19) | Ages 10–19 M age 14 50% Male. 65% White 13% Black 12% Latino 64% urban or suburban 32% low SES (eligible for school lunch) |

Past year carriage = 5% Past year carriage to school = 1% |

Demographic/Hangun Model: Across models, male gender, being seen as being cool if carrying a gun, less parental monitoring, and increased number of peers carrying guns was predictive of having ever carried, having ever carried to school, and having ever carried and having carried to school. SES was inconsistently associated. Attitudes favoring not taking a gun to school were protective. Violence/Delinquency Model: Across models, increased freq of aggression, gang membership, prior arrest, and substance use were associated with having ever carried, carrying to school, & having ever carried/carrying to school. Family, School, Community Models: Across models, no consistent findings regarding family, school, or community variables with regards to having ever carried, carrying to school, and having every carried/carrying to school |

Cross-sectional data Self-report data Survey distributed by untrained teachers rather than research staff No measures assessed victimization |

7 |

| Xuan and Hemenway (2015) | Cross-sectional Data was from the 2007, 2009, and 2011 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) |

228,904 | Nationally representative sample of 9th-12th graders drawn from 38 U.S. states | Not reported | Past 30-day gun carriage = 7% | Gun carriage among youth in 19 states with stronger gun laws was 5.7% compared to youth in the 19 states with weaker laws where carriage was 7.3%. A 10 point increase in firearm law score (i.e., strength of the gun laws for 5 areas—curbing firearm trafficking, stronger background checks, child safety laws, military assault-style weapon ban, and restricting guns in public places) was associated with a 9% reduction in the odds of youth gun carriage (AOR 0.9). Adult firearm ownership mediated the association between the state gun law score and youth gun carriage (AOR 0.9) with 29% attenuation of the regression coefficient | Cross-sectional data Self-report data Non-validated scoring for strength of state firearm laws Local policies were not included in the weighted firearm law scores |

5 |

Quality of included studies

There was considerable variation in study quality (n = 53), with NOS scores ranging from 4 to 7 (see Tables 1, 2, 3 for article scoring). In total, 18 articles (34%) scored a 7 or higher on the NOS scale (i.e., high quality). Longitudinal cohort (n = 17) and case control (n = 1) studies were consistently of moderate-to-high quality, while cross-sectional studies (n = 29) demonstrated considerable variability, with scores ranging from low-to-high quality. Although most studies employed validated measures, nearly all relied on self-report data subject to recall and social desirability bias. Most articles (55%) were cross-sectional.

Rates of carriage across studies included in this scoping review