Abstract

Multifocal ill-defined opacities most often result from multiple consolidations but must be distinguished from invasive or hemorrhagic tumors. This is not a common appearance for community-acquired pneumonia, but when it occurs this appearance indicates a serious infection that is likely caused by a virulent organism. Patients with a documented viral infection such as influenza who develop this pattern have most likely developed a superimposed bacterial pneumonia. Multifocal air space opacities are a common appearance for hospital-acquired pneumonias, especially for patients in the intensive care setting. Fungal pneumonias should be considered when the chest x-ray is suggestive of pneumonia and cultures for bacterial infection are negative. Immune compromised patients are at high risk for aggressive fungal infections. Multifocal air space opacities are not a common appearance for tuberculosis, but it must be excluded in patients who either present with associated cavities or develop cavities. Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma is the most likely tumor to have this appearance and must be considered in an afebrile patient with a chest x-ray that looks like a multifocal pneumonia. This is a rare appearance for chronic lung diseases, but it may result from sarcoidosis, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and silicosis or coal worker’s pneumoconiosis.

Keywords: actinomycosis, aspergillosis, blastomycosis, candidiases, coal worker’s pneumoconiosis, coccidioidomycosis, cryptococcosis, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, Escherichia coli, Haemophilus influenzae, histoplasmosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma, Klebsiella, Legionella, lymphoma, mucormycosis, Nocardia, Pseudomonas, sarcoidosis, silicosis, sporotrichosis, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus

Questions

-

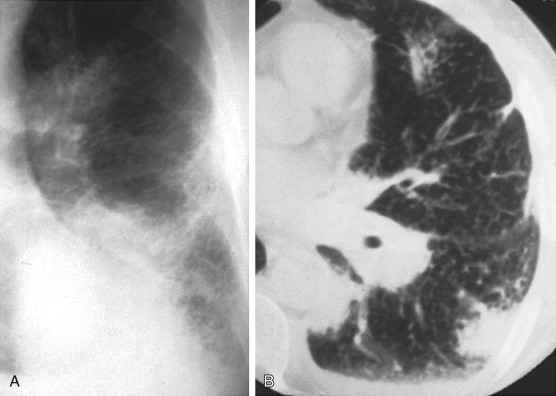

1.Which one of the following is the most likely diagnosis in the case seen in Fig. 16.1 ?

-

a.Tuberculosis.

-

b.Lung cancer

-

c.Melanoma.

-

d.Silicosis.

-

e.Pneumonia.

-

a.

-

2.Referring to Fig. 16.2 , the combination of hilar adenopathy and multifocal ill-defined opacities is most consistent with which one of the following?

-

a.Granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

-

b.Sarcoidosis.

-

c.Hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

-

d.Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

-

e.Choriocarcinoma.

-

a.

-

3.The presence of an air bronchogram throughout a large irregular opacity is inconsistent with which one of the following diagnoses?

-

a.Silicosis.

-

b.Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma.

-

c.Lymphoma.

-

d.Granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

-

e.Sarcoidosis.

-

a.

Fig. 16.1.

Fig. 16.2.

Discussion

Multifocal ill-defined opacities (see Fig 16.1) result from a great variety of diffuse pulmonary diseases (Chart 16.1 ). This pattern is sometimes referred to as a patchy alveolar pattern, but it should be contrasted with the bilaterally symmetric, diffuse, coalescing opacities described as the classic appearance of air space disease in Chapter 15. Many of the entities that cause multifocal ill-defined opacities do result in air space filling, but they also may involve the bronchovascular and septal interstitium. Acute diseases may present as patchy scattered opacities and progress to complete diffuse air space consolidation. Some of the additional signs of air space disease are also encountered in this pattern, including air bronchograms, air alveolograms, and a tendency to be labile.

Chart 16.1. Multifocal Ill-Defined Opacities.

-

I.Infectious diseases

- A.

- B.

-

C.Tuberculosis198,388,644198388644

-

D.Viral95,382,59995382599 and mycoplasma pneumonias170,250170250

-

E.Rocky Mountain spotted fever333,365333365

-

F.Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia

-

G.Paragonimiasis416

-

H.Q fever385

-

I.Atypical mycobacteria in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)363

-

J.Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)412

-

K.Septic emboli312,491312491

-

II.Autoimmune diseases

- III.

-

IV.Lymphoproliferative disorders

-

A.Non-Hodgkin lymphoma21,272127 (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue [MALT] lymphoma is most common)543

-

B.Hodgkin lymphoma (rarely primary in lung)

-

C.Lymphomatoid granulomatosis343,345,543343345543

-

D.Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder119

-

E.Mycosis fungoides264,362264362

-

F.Waldenström macroglobulinemia410,457410457

-

A.

-

V.Environmental diseases

-

A.Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (allergic alveolitis)86,299,565,57086299565570

-

B.Coal worker’s pneumoconiosis

-

C.Silicosis

-

A.

-

VI.Smoking-related diseases

-

A.Langerhans cell histiocytosis1,3551355

-

B.Desquamative interstitial pneumonitis (DIP)355,398355398

-

A.

- VII.

-

VIII.Other disorders

-

A.Drug reactions52,426,43452426434

-

B.Radiation pneumonitis384,425384425

-

C.Metastatic pulmonary calcification (secondary to hypercalcemia)158,228158228

-

D.Fat emboli

-

A.

Because many of the entities considered in the differential are in fact primarily interstitial diseases, complete examination of the chest radiograph may reveal an underlying fine nodular or reticular pattern. Distinction of this multifocal pattern from the fine nodular pattern may also become somewhat of a problem because the definition of the opacities is one of the primary distinguishing characteristics of the two patterns. The description for miliary nodules usually requires that the opacities be sharply defined, in contrast to the less defined opacities currently under consideration. Most entities considered in this differential produce opacities that are larger than 1 to 2 cm in diameter, in contrast to the fine nodular pattern in which the opacities tend to be less than 5 mm in diameter. Additionally, this pattern may result from diseases that cause multiple larger nodules and masses. Some tumors may be locally invasive and appear ill defined because of their growth pattern, whereas others may develop complications such as hemorrhage. Because the differential for multifocal ill-defined opacities is lengthy, its identification obligates the radiologist to review available serial examinations, carefully evaluate the clinical background of the patient, and recommend additional procedures.

Infectious Diseases

Bacterial Bronchopneumonia

Multiple areas of consolidation are the characteristic pattern of bacterial bronchopneumonia (see Fig 16.1; answer to question 1 is e). Because this type of infection spreads via the tracheobronchial tree, large areas of air space consolidation are often preceded by lobular opacities238 that tend to be ill defined because the fluid and inflammatory exudate that produce the opacities spread through the interstitial planes in addition to spilling into the alveolar spaces.235 In some cases, the lobular pattern may have sharply defined borders where the exudate abuts an interlobular septum. The size of the radiologic opacities depends on the number of contiguous lobules involved. Intervening normal lobules lead to a very heterogeneous appearance. As the infection progresses, the consolidations will begin to coalesce and form a pattern of multilobar consolidation (Fig 16.3 ) that may even become indistinguishable from the diffuse confluent pattern commonly associated with alveolar edema. This is a common pattern for hospital-acquired pneumonias.

Fig. 16.3.

Bilateral multifocal areas of consolidation caused by bronchopneumonia often progress with large areas of multilobar involvement. This patient has bilateral lower lobe consolidations with multiple smaller foci of pneumonia in the upper lobes. As the infection spreads this appearance of multilobar pneumonia may become more uniform and may even resemble pulmonary edema.

The radiologic patterns of bronchopneumonia are determined by the virulence of the organism and the host’s defenses. The primary sites of injury are the terminal and respiratory bronchioles. The disease starts as an acute bronchitis and bronchiolitis. The large bronchi undergo epithelial destruction and infiltration of their walls by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Epithelial destruction results in ulcerations that are covered with a fibrinopurulent membrane and that contain large quantities of multiplying organisms. As the inflammatory reaction spreads through the walls of the bronchioles to involve the alveolar walls, there is an exudation of fluid and inflammatory cells into the acinus, which results in the pattern of multifocal consolidations. As noted in Chapter 15, patients with bronchopneumonia occasionally have only one lobe predominantly involved, but there are almost always other areas of involvement. An unusually virulent organism or failure of the patient’s immune response leads to rapid enlargement of the multifocal opacities and, finally, to diffuse air space consolidations. This has been observed in patients infected by common organisms and those infected with unusual organisms, including those with Legionnaires’ disease and those infected by Legionella micdadei (Pittsburgh pneumonia agent).311,436311436 With more aggressive organisms, such as Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas, a necrotic bronchitis and bronchiolitis lead to thrombosis of lobular branches of the small pulmonary arteries, which accounts for the cavitation seen in necrotizing pneumonias such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA; see Chapter 24).

Septic Emboli

Septic emboli are another source of severe pulmonary infection that occurs when a bolus of infectious organisms are released into the blood and spread to the peripheral pulmonary vessels. The first radiologic signs of septic emboli are small, ill-defined peripheral opacities. As the infection spreads, the size of the opacities increases, leading to multifocal peripheral opacities. Septic embolization also has a high probability of cavitation, which makes it different from many of the other causes of this pattern. Clinical correlation is essential in the diagnosis of septic embolization. There should be a history of a significant febrile illness. Risk factors for septic embolism include sepsis, osteomyelitis, cellulitis, carbuncles, and right-sided endocarditis. Patients with right-sided endocarditis frequently have a history of intravenous drug abuse and are at increased risk for MRSA infection.

Viral Pneumonia

Viruses produce their effect in the epithelial cells of the respiratory tract, leading to tracheitis, bronchitis, and bronchiolitis.295 The bronchial and bronchiolar walls become very edematous, congested, and infiltrated with lymphocytes. The bronchial infiltrate may extend into the surrounding peribronchial tissues, which become swollen. This infiltrate spreads into the septal tissues of the lung, leading to a diffuse, interstitial, mononuclear, cellular infiltrate. The changes in the airways may extend to the alveolar ducts, but most severe changes occur proximal to the terminal bronchioles. The adjacent alveolar cells, both type 1 and type 2, become swollen and detached. These surfaces then become covered with hyaline membranes. In fulminant cases, there are additional changes in the alveoli. The alveoli are filled with a mixture of blood, edema, fibrin, and macrophages. In the most severely affected areas, there is focal necrosis of the alveolar walls and thrombosis of the alveolar capillaries, leading to necrosis and hemorrhage.

The radiologic pattern of a viral pneumonia depends on both the virulence of the organism and host defenses.50 The mildest cases of viral infection are confined to the upper airways and manifest no radiologic abnormality. The earliest radiologic abnormalities are the signs of bronchitis and bronchiolitis, which may include peribronchial thickening and signs of air trapping. When the infection spreads into the septal tissues, a reticular pattern with interlobular septal lines may result, as described in Chapter 18. The more serious cases lead to hemorrhagic edema and areas of air space consolidation. These opacities may be small and appear as a fine nodular pattern similar to that described in Chapter 17, but the nodules tend to be less well defined than the classic miliary pattern. As the process spreads, lobular consolidations develop, as in bacterial bronchopneumonia. In the most severe cases, the lobular consolidations may coalesce into diffuse consolidation, resembling pulmonary edema or bacterial bronchopneumonia.

Influenza viral pneumonia should be suspected in patients with typical influenza symptoms of fever, dry cough, headache, myalgia, and prostration. As the infection spreads to the lower respiratory tract, the patient notices an increased production of sputum that may be associated with dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, or both. Physical examination reveals rales that may be accompanied by diminished or harsh breath sounds. Because of the bronchial involvement, wheezes are occasionally noted. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) may reveal multifocal ground-glass opacities while the chest radiograph appears to be normal. The chest radiographic patterns evolve from a minimal reticular pattern to small, ill-defined nodules to lobular consolidations, and finally to diffuse confluent opacities. Influenza pneumonia may be complicated by adult respiratory distress syndrome or superimposed bacterial pneumonia. At this time, laboratory examination of the sputum and blood becomes paramount to rule out a superimposed bacterial bronchopneumonia. The organisms most likely to present a superimposed bacterial infection are pneumococci, staphylococci, streptococci, and H. influenzae. In this clinical setting, the development of a superimposed cavity virtually confirms a superimposed bacterial infection. Other causes of viral pneumonia are less commonly encountered in patients with normal immunity, but have been reported with hanta viruses, Epstein-Barr virus, adenoviruses,295 and SARS.412

Fulminating cases of viral pneumonia are rarely encountered in patients with normal immunity but may occur in patients with suppressed immune systems including those receiving high-dose steroid therapy, patients receiving chemotherapy, patients with AIDS, organ transplant patients, pregnant women, and older adults. Herpes simplex, varicella, rubeola, cytomegaloviruses, and adenoviruses occur mainly in immunocompromised patients.295

Varicella pneumonia characteristically occurs from 2 to 5 days after the onset of the typical rash. It is most commonly noted in infants, pregnant women, and adults with altered immunity. Approximately 10% of adult patients may have some degree of pulmonary involvement. In contrast to what is seen in bacterial pneumonias, sputum examination shows a predominance of mononuclear cells and giant cells. As in the consideration of other viral pneumonias, the possibility of superimposed bacterial infection is best excluded by laboratory examination of the sputum and blood. Because the viruses of herpes zoster and varicella are identical, patients with an atypical herpetic syndrome consisting of a rash with pain that follows the nerves of a single dermatome are also at increased risk for development of this type of pneumonia.

Rubeola (measles) pneumonia may be more difficult to diagnose by clinical criteria because the pneumonia occasionally precedes the development of the rash. As with other viral pneumonias, the clinical findings are nonspecific and consist of fever, cough, dyspnea, and minimal sputum production. Increasing sputum production requires exclusion of a superimposed bacterial pneumonia. Timing is important for evaluating a pneumonia associated with measles. The development of primary viral pneumonia in rubeola is synchronous with the first appearance of a rash, whereas secondary bacterial pneumonias are most likely to occur from 1 to 7 days after the onset of the rash. Bacterial infection is strongly suggested in the patient with a typical measles rash whose condition improves over a period of days before pneumonia develops. A third type of pneumonia associated with measles pneumonia is histologically referred to as giant cell pneumonia. This may follow overt measles in otherwise normal healthy children, but children with an altered immune system may develop subacute or chronic, but often fatal, pneumonias. Pathologically, giant cell pneumonia is characterized by an interstitial mononuclear infiltrate with giant cells.

Cytomegalic inclusion disease2 has few distinguishing clinical features, has a radiologic presentation suggestive of bronchopneumonia, and is frequently fatal in patients who are immunosuppressed. Histologically, the lung reveals a diffuse mononuclear interstitial pneumonia accompanied by considerable edema in the alveolar walls that may even spill into the alveolar spaces. In addition, the alveolar cells have characteristic intranuclear and intracytoplasmic occlusions. The radiologic opacities are the result of cellular infiltrates in the interstitium, as well as intra-alveolar hemorrhage and edema. Other viruses, including the coxsackie viruses, parainfluenza viruses, adenoviruses, and respiratory syncytial viruses, may result in disseminated multifocal opacities. When the course of the viral infection is mild, confirmation is rarely obtained during the acute phase of the disease, but may be made by viral culture or acute and convalescent serologic studies.

Rickettsial Infection

Rocky Mountain spotted fever is a lesser known cause of pulmonary vasculitis that may lead to the appearance of multiple areas of air space consolidation and even an appearance similar to that of pulmonary edema.333,365333365 This rickettsial infection also results in a diffuse vasculitis. It is best diagnosed by the clinical findings of a rash and central nervous system findings. A history of tick bite and an increase in antibody titers strongly support the diagnosis.

Granulomatous Infections

Histoplasmosis97 (Fig 16.4 ) is the most likely of the granulomatous infections to produce ill-defined multifocal opacities of varying sizes. This form of histoplasmosis is usually seen after a massive exposure to Histoplasma capsulatum. This organism is a soil contaminant found primarily in the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys, and histoplasmosis should be suspected when this pattern is seen in acutely ill patients from these endemic areas. A history of prolonged exposure to contaminated soil is frequently obtained and helps confirm the diagnosis. A marked rise in serologic titers is also confirmatory. The radiologic course is characterized by gradual healing of the process, involving contraction of the opacities; resolution of a large number of opacities; and the development of a pattern of scattered, more circumscribed nodules. This may precede the characteristic appearance of multiple calcifications that develops as a late stage of histoplasmosis.

Fig. 16.4.

Histoplasmosis is caused by a fungus and is well known to produce a radiologic appearance similar to that of lobular pneumonia.

Blastomycosis142,450142450 and coccidioidomycosis373 are two other fungal infections likely to result in this pattern. These fungi are also soil contaminants with a well-defined geographic distribution. Coccidioidomycosis is primarily confined to the desert Southwest of the United States, although the fungus may be found as a contaminant of materials such as cotton or wool transported from this area. The geographic distribution of blastomycosis is less distinct than that of histoplasmosis or coccidioidomycosis, but it is generally confined to the eastern United States, with numerous cases reported from Tennessee and North Carolina.

Opportunistic fungal diseases,98 such as candidiasis,173 cryptococcosis,502 aspergillosis,172,591172591 and mucormycosis, may produce this pattern but are rarely encountered in patients who are immunologically normal. Aspergillosis and mucormycosis33 are part of a small group of pulmonary infections that tend to invade the pulmonary arteries. These invasive fungal infections produce multifocal areas of consolidation as a result of pulmonary hemorrhage and infarction. Invasive aspergillosis is a cause of masses with ill-defined borders that may have the appearance of a halo on HRCT. Infarction causes cavities that are often filled with a mass of necrotic tissue that causes the appearance of an air crescent sign on both chest radiographs and computed tomography (CT) scans.524

Tuberculosis388 less commonly produces multifocal ill-defined opacities, but should be strongly considered in the case of an apical cavity followed by the development of this pattern. In such an instance, the opacities most probably are the result of bronchial dissemination of the organisms.

Large, poorly defined, mass-like opacities may form by the coalescence of small nodules.244 The diagnosis is confirmed by sputum stains for acid-fast bacilli or by cultures.

Autoimmune Diseases

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis235,457,460235457460 is a well-documented cause of the radiologic appearance of bilateral nodular or even mass-like foci (Fig 16.5, A and B ). These opacities often have ill-defined borders, sometimes becoming confluent and showing air bronchograms (see Fig 16.2). The clinical manifestation of sarcoidosis is in striking contrast to that of the other inflammatory conditions. Patients with sarcoidosis are afebrile and often virtually asymptomatic, although they may complain of mild dyspnea. This marked disparity of the radiologic and clinical findings virtually eliminates all of the entities considered so far in this chapter. When the pattern of multifocal ill-defined opacities is combined with bilaterally symmetric hilar adenopathy and the typical clinical presentation of the disease, the diagnosis becomes nearly certain. In this diffuse pulmonary disease, the diagnosis is easily confirmed by transbronchial biopsy.

Fig. 16.5.

A, Multifocal opacities often resemble nodules and masses. B, The presence of air bronchograms and less well-defined borders on this computed tomography scan make metastatic nodules a less likely diagnosis. This is a multinodular manifestation of sarcoidosis.

The pathologic explanations for this presentation of sarcoidosis have stimulated considerable discussion in the radiologic literature. Some authors describe this pattern as nodular sarcoidosis, whereas others consider it to be an alveolar sarcoidosis. The radiologic features supporting the appearance of alveolar sarcoidosis are primarily those of confluent opacities with ill-defined borders, which may contain air bronchograms. It should be noted that sarcoidosis rarely causes bilaterally symmetric confluent opacities with a bilateral perihilar (butterfly) distribution, as seen in alveolar edema, pulmonary hemorrhage, or alveolar proteinosis. Consequently, sarcoidosis is not a serious consideration in the differential of the pattern considered in Chapter 15. Heitzman235 reported histologic evidence that patients with this “alveolar pattern” may have massive accumulations of interstitial granulomas, which by compression of air spaces could mimic an alveolar filling process. This is essentially a form of compressive atelectasis. The histologic observation of a massive accumulation of interstitial granulomas can easily be confirmed by examination of a number of cases with this radiologic pattern. Therefore, this mechanism almost certainly accounts for some cases with this pattern.

One feature of the consolidation of sarcoidosis that is not readily explained by the foregoing observation is their very labile character. Frequently, the opacities accumulate and disappear dramatically, either spontaneously or in response to steroid treatment. It seems unlikely that a massive accumulation of well-organized granulomas could resolve in a matter of days or even a few weeks. Another explanation for this radiologic pattern of fluffy opacities with ill-defined borders and air bronchograms is based on the frequent presence of peribronchial granulomas that cause bronchial obstructions. Peribronchial granulomas are frequently observed on bronchoscopy and HRCT.335 Distal to these bronchial obstructions there is, in fact, alveolar filling, not by sarcoid granulomas but by macrophages and proteinaceous material. Histologically, this pattern is basically an obstructive pneumonia. The clinical variability of alveolar sarcoidosis is probably accounted for by these two major histologic explanations. For instance, the confluent heavy accumulation of sarcoid granulomas with resultant compressive atelectasis would not be expected to resolve in a short time, whereas the smaller accumulations of granulomas in the peribronchial spaces with distal obstruction could account for cases that follow a much more labile course and respond dramatically to steroid therapy. It should be emphasized that obstructive pneumonia in sarcoidosis is secondary to the obstruction of small distal bronchi and bronchioles. It is very rare for sarcoid granulomas to obstruct large bronchi and produce lobar atelectasis.

Granulomatosis

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis and its variants are probably the best-known sources of pulmonary vasculitis.146,343,345146343345 Clinical correlation is extremely important because the classic form is associated with severe paranasal sinus and kidney involvement. A history of multifocal ill-defined opacities on the chest radiograph, hemoptysis, and hematuria strongly suggests granulomatosis with polyangiitis or one of its variants. The opacities appearing on the chest radiograph are areas of edema, hemorrhage, or even lung tissue necrosis. Ischemic necrosis results in cavitary opacities in approximately 25% of patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis. These opacities are more likely to be the result of the vasculitis with ischemia than to the granulomas. Perivascular granulomas, in fact, may be very small and may contribute minimally to the radiologic opacities. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis frequently requires careful histologic evaluation to differentiate it from other diseases that have been referred to as the pulmonary renal syndromes, including Goodpasture syndrome and idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis.

Neoplasms

Neoplasms are not generally regarded as a common cause of multifocal ill-defined opacities in the lung. However, there are a few neoplasms that do produce this pattern and are somewhat characteristic in their radiologic appearance when compared with other pulmonary tumors.

Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma457,587,597,598457587597598 (Fig 16.6 ) is the primary lung tumor most likely to produce the radiographic appearance of multifocal ill-defined opacities, which often have air bronchograms.647 The biologic behavior of this tumor is significantly different from that of most other primary lung tumors because it tends to spread along the alveolar walls while leaving them intact. At the same time the tumor spreads along the walls, there is a tendency for it to produce significant amounts of mucus, which may contribute to the ill-defined opacities. The preservation of the underlying lung architecture permits the tumor to spread around open bronchi and gives rise to air bronchograms. This radiologic pattern of multifocal ill-defined opacities resembles bronchopneumonia and requires careful clinical correlation. The HRCT patterns of invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma are usually a mixture of ground-glass opacities and air space consolidations with air bronchograms.575

Fig. 16.6.

Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma fills the air spaces with mucus and tumor cells. Bronchogenic dissemination accounts for the appearance of multifocal air space opacities that may progress to cause extensive consolidations.

Metastases rarely present as multifocal opacities with ill-defined borders. The ill-defined borders likely result from the superimposition of a large number of masses and nodules or from the invasive growth of masses into the surrounding lung. Poorly marginated metastases may also result from surrounding opacities, including atelectasis or bleeding that obscures the margin of the masses. It has been suggested that choriocarcinoma is frequently complicated by bleeding around the periphery of the tumor, giving the radiologic appearance of ill-defined opacities. However, Libshitz et al.341 have presented more than 100 cases showing that this occurrence is exceptional.

Lymphoproliferative Disorders

Lymphoma21,328,457,46021328457460 is the most common of the pulmonary lymphoproliferative disorders, with non-Hodgkin lymphoma being the most common (Fig 16.7, A and B ). The MALT subtype of B cell lymphoma is the most common primary lymphoma of the lung, but primary lymphoma of the lung is rare at 1% of all lung malignant tumors.543 When lymphoma involves the lung parenchyma, primarily or secondarily, it spreads via the perivascular and peribronchial tissues and even by way of the interlobular septa. Histologically, its spread is considered to be an interstitial process. However, it is also well known that lymphomatous involvement of the lung may present with consolidative opacities that have ill-defined borders and air bronchograms.337 There are at least three feasible explanations for this radiographic appearance of lymphoma: (1) the massive accumulation of tumor cells may destroy the alveolar walls and break into the alveolar spaces; (2) there may essentially be a compressive atelectasis or collapse of the alveolar spaces by the massive accumulation of lymphoma cells in the interstitium; and (3) because of the peribronchial infiltration, there may be an obstructive pneumonitis with secondary filling of the distal air spaces by fluid and inflammatory cells rather than by lymphoma cells.

Fig. 16.7.

A, Pulmonary lymphoma is a cause of poorly circumscribed masses that may resemble consolidations. This case shows a large opacity in the left lower lobe, a peripheral subpleural opacity, and an opacity above the left hilum. There is also a subtle, diffuse, fine reticular pattern. B, Computed tomography section of the same case of lymphoma shows multiple ill-defined opacities. There is an air bronchogram through the most anterior opacity, which has the appearance of a consolidation. There is also diffuse thickening of the interlobular septae. These findings are all the result of lymphomatous masses and interstitial infiltration.

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis was described by Liebow343 and Liebow et al345 as an angioinvasive, lymphoproliferative B cell disorder. It involves the lungs but may also involve the skin and central nervous system. Chest radiographic findings include multifocal consolidations, nodules, and masses. Minimal adenopathy has been found in a small number of cases and probably represents reactive hyperplasia.543 The presence of lymphadenopathy should probably be regarded as a warning to question the diagnosis and suspect progression to lymphoma.

Environmental Diseases

The environmental diseases most frequently associated with the pattern of multifocal ill-defined opacities include acute hypersensitivity pneumonitis, silicosis, coal workers’ pneumoconiosis,299,429,565,570299429565570 and some of the smoking-related diseases.

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis is an allergic reaction at the alveolar capillary wall level to mold and other organic irritants. Initially it is an acute reaction consisting of edema with an inflammatory infiltrate in the interstitium. This inflammatory infiltrate may gradually be replaced by a granulomatous reaction with some histologic similarities to sarcoid granulomas. The multiple confluent opacities with air bronchograms tend to represent the acute phase of the disease, and a nodular or even a reticular pattern may be seen in the later stages. Confirmation of the diagnosis is best obtained by establishing a history of exposure followed by skin testing, serologic studies, and correlation with HRCT. Exposure histories are varied; they include molds and fungi from sources such as moldy hay in farmer’s lung, bird fancier’s disease, bagassosis from mold in sugar cane, mushroom worker’s lung, and hot tube lung. Hot tube lung may differ from the other causes of hypersensitivity pneumonitis in that it is a reaction to Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC)227 rather than to molds.

Silicosis and coal workers’ pneumoconiosis are inhalational diseases that frequently result in multiple opacities. The border characteristics of these opacities are quite different from those considered in the remainder of this discussion. These borders tend to be more irregular rather than truly ill defined. The irregularities are the result of strands of fibrotic reaction around the conglomerate masses. In addition, the opacities tend to be much more homogeneous because they represent large masses of fibrotic reaction. There should be no normal intervening alveoli to give a soft heterogeneous appearance. Furthermore, there should be no evidence of air bronchograms. (Answer to question 3 is a.) These opacities tend to be in the periphery of the lung with an upper lobe predominance. However, they are frequently not pleural-based; rather, they appear to parallel the chest wall. The opacities are usually bilateral but may be asymmetric. As they enlarge, they are often mass-like and described as progressive massive fibrosis (Fig 16.8 ). A history of exposure in mining or sandblasting is usually confirmatory. Coal workers’ pneumoconiosis is radiologically indistinguishable from silicosis. Comparison with old examinations is essential to ensure stability and eliminate the possibility of a new superimposed process, such as tuberculosis or neoplasm.

Fig. 16.8.

Upper lobe opacities in this case of coal workers’ pneumoconiosis are similar to those of other cases in this chapter. The associated coarse reticular opacities are the result of interstitial scars. Progressive fibrosis causes the larger opacities to have irregular rather than ill-defined borders. This is often described as progressive massive fibrosis.

Smoking-Related Diseases

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a smoking-related1,3551355 inflammatory condition that may present with a variety of patterns, including nodules ranging in size from 1 to 10 mm.1 The nodular opacities are caused by a granulomatous infiltrate with histiocytes, eosinophils, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and Langerhans cells. The nodular phase of the disease is generally believed to represent an early stage of the disease, which precedes the development of reticular opacities, small cavities, or multiple cysts. There is typically an upper lobe predominance in the nodular, reticular, and cystic phases of the disease. HRCT should confirm the presence of nodular and reticular opacities with an upper lobe distribution and is very sensitive for the detection of small peripheral cavities and cystic spaces42,31942319 (Fig 16.9, A and B ). LCH is an afebrile illness with much milder symptoms than all of the infectious diseases hitherto considered.

Fig. 16.9.

A, Langerhans cell histiocytosis is a cause of multifocal, poorly defined nodular opacities with a tendency toward an upper lobe predominance, as illustrated by this case. B, High-resolution computed tomography section through the upper chest reveals multiple, poorly defined nodular opacities with interspersed, coarse, reticular opacities.

DIP causes filling of the alveoli with macrophages and minimal interstitial fibrosis. In contrast with LCH, it produces ground-glass opacities with a peripheral basilar distribution.20 The chest radiograph may reveal subtle opacities in the periphery of the lung bases that are difficult to characterize and are best evaluated with HRCT.

Idiopathic Diseases

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP),329 formerly known as bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia (BOOP), is a subacute or chronic inflammatory process involving the small airways and alveoli. COP has extensive alveolar exudate and fibrosis that may resemble or overlap the changes of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), but COP can usually be distinguished from UIP. COP has multifocal air space opacities with normal lung volume, whereas UIP has irregular reticular opacities with reduced lung volume. The radiologic presentation resembles that of bronchopneumonia (Fig 16.10, A and B ); patients with the disease are often unsuccessfully treated with antibiotics on the basis of a presumed diagnosis of pneumonia. Corticosteroid therapy has been reported to produce clearing of the radiologic abnormalities, but there is a high relapse rate following steroid withdrawal.

Fig. 16.10.

A, Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia produces multifocal ill-defined opacities that resemble bronchopneumonia. B, Computed tomography scan reveals multifocal air space consolidations with a halo of peripheral ground-glass opacities and a lower lobe predominance.

Eosinophilic pneumonias85,181,34485181344 with peripheral eosinophilia or eosinophilic infiltrates of the lung are often of unknown cause but may occur as a drug reaction or as a response to parasites. Radiologically, these infiltrates appear as patchy areas of air space consolidation that tend to be in the periphery of the lung86 (Fig 16.11 ). When these eosinophilic infiltrates become extensive, the radiologic picture has been compared with a photonegative picture of pulmonary edema because of the striking peripheral distribution of the opacities.181 These opacities have very ill-defined borders, tend to be coalescent, and frequently have air bronchograms.

Fig. 16.11.

Eosinophilic pneumonia typically produces multifocal ill-defined opacities that tend to be in the periphery of the lung. This is often described as the photonegative of pulmonary edema. Note the peripheral opacities with a clear area between the opacities and central pulmonary arteries.

There are two important groups of eosinophilic pneumonias. The first group consists of the idiopathic varieties of eosinophilic pneumonia that are generally divided into those associated with peripheral eosinophilia, referred to as Loeffler syndrome, and those that are comprised primarily of eosinophilic infiltrates in the lungs without peripheral eosinophilia, referred to as chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. Besides tending to be peripheral, the infiltrates have the additional characteristic of being recurrent and are frequently described as fleeting.175

The second group of pulmonary infiltrates associated with eosinophilia includes those with a known causal agent. A variety of parasitic conditions are associated with pulmonary infiltration and are likewise well known for the association of eosinophilia. These include ascariasis, Strongyloides infection, hookworm disease (ancylostomiasis), Dirofilaria immitis and Toxocara canis infections (visceral larva migrans), schistosomiasis, paragonimiasis, and, occasionally, amebiasis.175

Correlation of the clinical, laboratory, and radiologic findings often makes a precise diagnosis of parasitic disease a straightforward matter. For example, T. canis infection results from infestation by the larva of the dog or cat roundworm and has a worldwide distribution. The disease is most commonly encountered in children. The symptoms are nonspecific, but there is usually the physical finding of hepatosplenomegaly. There is also marked leukocytosis. In addition, a liver biopsy usually reveals eosinophilic granulomas containing the larvae.

The diagnosis of ascariasis is similarly made by laboratory identification of the organism. Larvae may be detected in sputum or gastric aspirates, whereas the adult forms of ova may be found in stool. The disease is usually associated with a marked leukocytosis and eosinophilia. As mentioned earlier, the chest radiographic appearance is that of nonspecific multifocal areas of homogeneous consolidation that are frequently transient and therefore virtually identical to the opacities described as Loeffler syndrome. Strongyloidiasis, like ascariasis, produces mild clinical symptoms at the same time that the radiograph demonstrates peripheral ill-defined areas of homogeneous consolidation. The diagnosis is made by finding larva in the sputum or in the stool. Exceptions to this clinical course occur in the compromised host. A fatal form of strongyloidiasis has been reported in patients who are immunologically compromised, particularly by corticosteroids.175

Amebiasis is different from the other parasitic diseases in both its clinical and radiologic presentations. Patients with amebiasis frequently have symptoms of amebic dysentery and complain of right-sided abdominal pain, which is related to the high incidence of liver involvement. There is often elevation of the right hemidiaphragm because of liver involvement and, as in other cases of subphrenic abscess, there is frequently right-sided pleural effusion. Furthermore, the areas of homogeneous consolidation are not evenly distributed throughout the periphery of the lung, as in other cases of eosinophilic infiltration, but tend to be in the bases of the lungs, particularly in the right lower lobe and right middle lobe. Because the opacities correspond to areas of abscess formation, they occasionally develop cavities.175

AIDS-Related Diseases

Pneumocystis is one of the most common pulmonary infections in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). It most often presents with a pattern of uniform bilateral reticular or confluent opacities that often resemble noncardiac pulmonary edema. The appearance of scattered or patchy opacities requires consideration of a greater variety of both infections and neoplasms including bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial pneumonias, and neoplasms such as lymphoma and Kaposi sarcoma.538

Bacterial pneumonias produce the same patterns in patients with HIV infection as in the general population.106 They are the most likely infections during the early stages of HIV infection while immune impairment is mild, with CD4 cell counts between 200 and 500 cells/μl,36 and in patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common organism, but more virulent organisms such as Staphylococcus should be suspected when the pneumonias are complicated by cavitation.

Tuberculosis in patients who have early HIV infection (CD4 counts between 200 and 500 cells/μl) produces the same patterns seen in patients with normal immunity.223,531223531 At this early stage, tuberculosis usually causes apical disease with cavitation. The bronchial dissemination of organisms from an apical cavity may lead to multifocal opacities that resemble bacterial bronchopneumonia. Following the development of AIDS after the CD4 count is lower than 200 cells/μl, patients are at increased risk for miliary tuberculosis515 with a fine nodular pattern (see Chapter 17), or multifocal air space opacities with hilar or mediastinal adenopathy resembling primary infection.203

Fungal infections are less frequent. However, candidiasis, cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, and coccidioidomycosis have all been reported to produce patterns similar to tuberculosis in patients with AIDS.93,98,5559398555

MAC infection most frequently causes diffuse, bilateral, reticular, and nodular opacities in patients with AIDS.363 In contrast, the patients with normal immunity who are at greatest risk for MAC infection are those with chronic pulmonary disease. In this latter group of patients, MAC may be radiographically indistinguishable from tuberculosis. The reticular pattern of MAC should be coarser and more disorganized than Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP); however, when PCP is chronic, it may result in a similar appearance. When MAC causes air space opacities, the air space opacities are segmental or multifocal, and the multifocal opacities are likely to resemble poorly circumscribed masses. The air space opacities are also often associated with pleural effusions or adenopathy, which may also be seen in tuberculosis but are not expected in pneumocystis pneumonia. Disseminated MAC is a terminal infection that occurs after the CD4 count has declined below 50 cells/μl.

Lymphoma may cause multiple poorly defined masses or multiple nodules. Lymphoma in patients with HIV is usually β-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma94 and differs from patients with normal immunity in that AIDS-related lymphomas are more often extranodal.328,539328539 Lymphoma is probably the most likely diagnosis of lobulated pulmonary masses in patients with AIDS. These masses often show a very aggressive growth pattern and may double in size within 4 to 6 weeks.

Kaposi sarcoma is the most common AIDS-related neoplasm,94 but has decreased in frequency for unexplained reasons. It is a highly vascular tumor that involves any mucocutaneous surface and produces characteristic red plaques. It is usually a skin lesion, but it also involves the trachea, bronchi, and lungs. The radiographic appearance of pulmonary opacities may result from atelectasis, hemorrhage, or hemorrhagic masses. Multiple nodules or masses are the most common pattern. More confluent, patchy, air space opacities may resemble PCP. Associated adenopathy or pleural effusions are reported to occur in 90% of patients with Kaposi sarcoma and may help distinguish Kaposi sarcoma from PCP, but their occurrence would not permit the exclusion of mycobacterial infection. Sequential thallium and gallium scanning has been advocated as a technique for distinguishing PCP, Kaposi sarcoma, and lymphoma. Pneumocystis is thallium negative but gallium positive on 3-hour delayed images. Lymphomas are thallium and gallium positive, and Kaposi sarcoma is thallium positive but gallium negative.332 Bronchoscopy may establish the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy has also been advocated for the diagnosis of focal and multifocal lesions.524 Lymphoma is an aggressive and often fatal neoplasm, in contrast to Kaposi sarcoma, which is an indolent, slow-growing tumor that is rarely fatal.

Top 5 Diagnoses: Multifocal Ill-Defined Opacities

-

1.

Pneumonia

-

2.

Sarcoidosis

-

3.

Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma

-

4.

Granulomatous pneumonias

-

5.

Septic emboli

Summary

Small multifocal ill-defined opacities are distinguished from miliary nodules by evaluation of their borders. Miliary nodules should be sharply defined.

Multifocal ill-defined opacities most commonly result from processes that involve both the interstitium and air spaces. Careful evaluation of the chest radiograph frequently reveals the classic signs for both components of the disease.

Bacterial bronchopneumonias typically present with this pattern, which is a common appearance of hospital-acquired pneumonias.

Histoplasmosis is one of the most common fungi to produce the pattern.

Unusual pulmonary infections, including aspergillosis, mucormycosis, cryptococcosis, and nocardiosis, may lead to the pattern in the patient who is immunocompromised.

Sarcoidosis causes this pattern when there are extensive accumulations of granulomas or when small granulomas occlude bronchioles with a resultant obstructive pneumonia.

Eosinophilic pneumonias should be suspected when the opacities are peripherally located and are recurrent or fleeting.

The large opacities seen in granulomatosis with polyangiitis frequently represent areas of necrosis or of hemorrhage and edema resulting from ischemia. Remember, this is a disease of the vessels.

Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma is the only primary lung tumor that is expected to produce this pattern.

Lymphoma and other lymphoproliferative disorders of the lung are rare, but this is their most likely appearance. MALT lymphomas are the most common type of primary pulmonary lymphoma.

Kaposi sarcoma in patients with AIDS is an important cause of this pattern. These patients usually have advanced cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. The pulmonary involvement must be distinguished from lymphoma and opportunistic infection. For unexplained reasons, the incidence of Kaposi sarcoma is declining.

Metastases rarely lead to this pattern but some may be invasive, hemorrhagic, or numerous masses may be superimposed.

Silicosis and coal workers’ pneumoconiosis may cause large, bilateral, irregular, upper lobe masses (conglomerate masses). They are fibrotic and should therefore not produce air bronchograms. Peripherally, their margins often parallel the lateral pleura.

Drug reactions frequently result in this pattern. They are best diagnosed by clinical correlation. Biopsy is frequently required in the patient who is immunocompromised to rule out opportunistic infection.

Answer Guide

Legends for introductory figures

-

Fig. 16.1

Multifocal ill-defined opacities are a common pattern for bronchial spread of infection and are a common appearance of hospital-acquired pneumonias.

-

Fig. 16.2

The multifocal ill-defined opacities in this case are very nonspecific, but the observation of enlargement of the nodes in the aortic pulmonary window (left arrows) and paratracheal lymph nodes (right arrows) combines two patterns and thus narrows the differential. Either sarcoidosis or lymphoma could account for this combination. The fact that the patient is relatively asymptomatic supports the correct diagnosis of sarcoidosis.

Answers

-

1.

e

-

2.

b

-

3.

a