Abstract

Minority stress theory describes the excess stressors to which individuals from stigmatized groups are exposed as a result of their marginalized status(es), which can contribute to higher rates of depression among sexual and gender minority (SGM) individuals. The psychological mediation framework expanded on minority stress theory by proposing that rumination may link minority stressors to depression. Although previous studies have shown that rumination mediates associations between minority stressors and psychological distress among SGM individuals, many have done so using cross-sectional data, despite mediation being a process that occurs over time. To address this limitation, the present longitudinal study examined rumination as a mediator of the associations of three minority stressors (i.e., victimization, microaggressions, and internalized stigma) with depressive symptoms among 1,130 young men who have sex with men (YMSM) and young transgender women (YTW). The data were taken from baseline, 6-month, and 1-year assessments from a large cohort of YMSM and YTW. Consistent with hypotheses, rumination at 6-month follow-up fully longitudinally mediated associations between victimization, microaggressions, and internalized stigma at baseline and depression at 1-year follow-up. Results suggest that rumination is an important area of intervention for clinicians treating SGM individuals who experience symptoms of depression.

Keywords: sexual minority, gender minority, minority stress, rumination, depression

Summary:

This study supports the notion that for sexual and gender minority individuals, experiencing excess stress as a result of their marginalized status may lead to a repetitive focus on these stressful experiences, which, in turn, may lead to symptoms of depression over time.

Sexual and gender minority (SGM) individuals, particularly SGM youth, experience higher levels of depression than non-SGM individuals (Borgogna, McDermott, Aita, & Kridel, 2019; Cochran, Sullivan, & Mays, 2003; Marshal et al., 2013; Mills et al., 2004; Mustanski, Garofalo, & Emerson, 2010), which represents an important area for intervention and prevention. SGM individuals with depressive symptoms are more likely to experience substance abuse (Sérráno & Wiswell, 2018; Weber & Dodge, 2018), suicidal ideation (Perez-Brumer, Day, Russell, & Hatzenbuehler, 2017), and suicide attempts (Peter & Taylor, 2014). In order to effectively address increased rates of depression among young SGM people, it is crucial to understand the mechanisms that contribute to its prevalence.

In an effort to explain the higher occurrence of mental disorders in SGM individuals, Meyer (2003) offered minority stress theory, which differentiates the excess stress to which individuals from stigmatized groups are exposed as a result of their marginalized status(es) from the general stressors to which all individuals may be exposed. Minority stress processes range from distal, which describes external, objective events and conditions, to proximal, which are more subjective and related to self-identity. Distal minority stressors can include experiences of victimization, as well as less overt forms of discrimination, such as microaggressions, which are often unintentional behaviors and statements that communicate hostile messages to members of stigmatized groups (Nadal, Whitman, Davis, Erazo, & Davidoff, 2016). Proximal stress processes may include internalized stigma, or the internalization of negative societal attitudes (Meyer, 2003). A wealth of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies based on the minority stress framework have shown that distal (i.e., victimization, microaggressions) and proximal (i.e., internalized stigma) minority stress processes are linked to greater symptoms of depression among SGM individuals (Birkett, Newcomb, & Mustanski, 2015; Bissonette & Szymanski, 2019; Dyar & London, 2018; Newcomb & Mustanski, 2010; Pachankis, Sullivan, Feinstein, & Newcomb, 2018; Salim, Robinson, & Flanders, 2019; Tucker et al., 2016).

Hatzenbuehler’s (2009) psychological mediation framework expanded Meyer’s (2003) theory by proposing that the increased stress to which SGM individuals are exposed as a result of their stigmatized identities leads to increases in emotion regulation processes, which in turn mediate the relationship between stigma-related stress and psychopathology. Emotion regulation refers to the “conscious and nonconscious strategies [people] use to increase, maintain, or decrease one or more components of an emotional response” (Gross, 2001, p. 215). One maladaptive emotion regulation strategy is rumination: the tendency to passively and repetitively focus on symptoms of distress and the circumstances surrounding these symptoms (Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008). Rumination prolongs and exacerbates psychological distress and is a serious risk factor for the development of symptoms of depression, as well as the onset and maintenance of depressive disorders (Morrison & O’Connor, 2005; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008; Rottenberg, Kasch, Gross, & Gotlib, 2002).

Chronic stigmatizing experiences may contribute to the development of rumination among SGM individuals in part because they contribute to increased hypervigilance, or attentional focus on one’s external environments and internal states (Major & O’Brien, 2005; Mays, Cochran, & Barnes, 2007; Mendoza-Denton, Downey, Purdie, Davis, & Pietrzak, 2002), which is an element of rumination (Lyubomirsky, Tucker, Caldwell, & Berg, 1999). Increased hypervigilance may be a result of chronic minority stress because it leads to thoughts and anxiety related to both past and future potential experiences of discrimination and rejection (Meyer, 2003). A previous longitudinal study in support of this theory found that SGM individuals were more likely to engage in rumination than their heterosexual peers (Hatzenbuehler, McLaughlin, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2008), and, in a daily dairy study, rumination occurred more on days when experiences of victimization were reported than on days when they were not reported (Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Dovidio, 2009). Consistent with the idea that distal minority stress experiences increase rumination via hypervigilance (i.e., because of concerns about future discrimination and rejection) two cross-sectional studies found that discrimination was positively associated with expectations of rejection, which was in turn associated with increased rumination; rumination, in turn, was related to increased psychological distress (Liao, Kashubeck-West, Weng, & Deitz, 2015; Timmins, Rimes, & Rahman, 2019). Microaggressions, which are more subtle forms of discrimination, may be likely to lead to rumination because the nature of the experiences are more ambiguous, can be perpetrated with non-malicious intentions by people who hold egalitarian beliefs, and are accepted by others who are present (Nadal et al., 2011). The ambiguity inherent in microaggressions may be particularly likely to result on repetitive focus on the experiences of them and the distress they cause (Kaufman, Baams, & Dubas, 2017).

Although Hatzenbuehler (2009)’s model focused specifically on distal minority stress processes (i.e., objective prejudice events), rumination may result from proximal minority stress (i.e., internalized stigma) as well. For example, Szymanski, Dunn, and Ikizler (2014) examined rumination as a mediator of the association between internalized heterosexism and psychological distress, arguing that the more an individual incorporates negative societal attitudes toward sexual minorities into their own self-perception, the more they may experience cognitive dissonance, because these negative attitudes conflict with their core identities (Festinger, 1962; Reilly & Rudd, 2006). Rumination may occur as a way of trying to resolve this cognitive conflict. The expenditure of cognitive effort involved in focusing on past and future distressing experiences of discrimination, and how it impacts one’s identity, may in turn impact psychological functioning and result in symptoms of depression.

Several previous studies have found that rumination mediated links between both distal and proximal minority stressors and psychological distress among SGM individuals. In experimental and daily diary studies, Hatzenbuehler and colleagues (2009) found that rumination mediated associations between external heterosexism and distress. A cross-sectional study found that sexual orientation microaggressions were associated with increased depressive symptoms via rumination (Kaufman et al., 2017). Szymanski and colleagues (2014), in another cross-sectional study, found that both heterosexist events and internalized heterosexism uniquely predicted psychological distress, and that rumination mediated the internalized heterosexism-distress link (but not the link between heterosexist events and distress). Finally, a daily diary study on anti-gay attitudes held by lesbian, gay, and bisexual participants (another proximal minority stressor) found that respondents with greater implicit anti-gay attitudes engaged in significantly more rumination, and that rumination fully mediated the association between implicit prejudicial attitudes and psychological distress (Hatzenbuehler, Dovidio, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Phills, 2009).

Although these studies can provide some evidence of associations among minority stressors, rumination, and depression, many of them utilize cross-sectional data, which limits their ability to test if rumination mediates the relations between predictors and outcomes. This is because mediation, by definition, is a process that unfolds over time, and one of the basic assumptions of this process is that time must elapse between each of the variables (MacKinnon, 2008; O’Laughlin, Martin, & Ferrer, 2018). Despite their widespread use to conduct mediation analyses, cross-sectional data can misrepresent the mediation of longitudinal processes (O’Laughlin et al., 2018). Thus, more research testing longitudinal mediation models is needed to develop a more accurate understanding of the causal process whereby rumination mediates relations between distal and proximal minority stressors and depression among SGM individuals.

The current study is focused specifically on SGM youth, who represent a group that is particularly vulnerable to depression. The transition from childhood to adulthood is a developmentally challenging period, particularly for youth who are SGM. Findings from the Youth Risk Behavioral Surveillance System (YRBS) have shown that 60% of SGM youth felt sad or hopeless almost every day for at least two weeks in the past year (Kann et al., 2016), and a recent meta-analysis found that prominent risk factors for depression for SGM youth include internalized stigma and victimization in school and community settings (Hall, 2018). This study represents an important contribution to research identifying key risk factors for depression among SGM youth, which are crucial to reduce the disproportionate burden of depression that they experience.

The goal of the current study is to examine rumination as a mediator of the associations of distal (i.e., victimization, microaggressions) and proximal (i.e., internalized stigma) minority stressors with depressive symptoms among young men who have sex with men (YMSM) and young transgender women (YTW). To address limitations of previous cross-sectional studies, the current longitudinal study uses data from three time points: baseline (Time 1), 6-month follow-up (Time 2), and 1-year follow-up (Time 3). In addition, we will use a multivariate approach to test the three mediating effects simultaneously, to allow us to examine the unique contributions of each minority stress variable to rumination and depression. We hypothesized that associations of all minority stress variables at Time 1 with depression at Time 3 would be mediated by rumination at Time 2.

Method

Procedure

Data for this study were collected as a part of RADAR, an ongoing longitudinal cohort study of HIV, substance use, and romantic/sexual relationships among YMSM and YTW in the Chicago area. Eligibility criteria at original cohort enrollment were: 16–29 years old, assigned male at birth, English-speaking, and had sex with a man in the past year or identified with a sexual or gender minority label. Participants were recruited in several ways: In-person and online recruitment; participants from previous cohort studies were enrolled; and serious partners and peers of enrolled participants were invited. More information about the recruitment process for the RADAR cohort study can be found in Mustanski et al. (2018). The current study uses data from the baseline assessment, 6-month, and 1-year follow-up assessments, which were collected in February 2015, August 2015, and February 2016. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Participants

Participants were 1,130 YMSM and YTW. At baseline, participants’ average age was 21.38 years (SD = 3.02). Participants identified their gender identity as male (92.1%), transgender: male-to-female (5.2%), or another identity not listed (2.7%). Participants identified as gay (69.8%), bisexual (20.9%), queer (3.3%), straight/heterosexual (1.7%), unsure/questioning (1.5%), lesbian (0.1%), or another orientation not listed (2.7%). Participants identified their race/ethnicity as Black or African American (33.6%), Hispanic/Latino(a) (30.2%), White (25.1%), Multi-racial (7.8%), Asian (2.4%), American Indian or Alaska Native (0.2%), Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (0.2%), or another identity not listed (0.6%).

Measures

Victimization.

Participants completed a six-item measure adapted from the work of D’Augelli and colleagues (1992; D’Augelli, Pilkington, & Hershberger, 2002; Pilkington & D’Augelli, 1995) designed to assess prevalence of LGBT-related victimization and harassment in the past six months (Mustanski, Andrews, & Puckett, 2016). Participants are instructed to report how often each event occurred because they are, or were thought to be, gay, bisexual, or transgender (e.g., “How many times have you been threatened with physical violence because you are, or were thought to be gay, bisexual, or transgender?”). Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale from 0 (never) to 3 (three times or more). Items were averaged into a single composite score, with higher scores reflecting higher frequency of victimization (Time 1 α = .85). The measure showed good internal consistency in a sample of LGBTQ youth (Chesir-Teran & Hughes, 2009).

Microaggressions.

The Sexual Orientation Microaggressions Inventory (SOMI; Swann, Minshew, Newcomb, & Mustanski, 2016) consists of 26 items developed based on themes detailed by Nadal, Rivera, and Corpus (2010). Participants are instructed to report how often in the past six months they have had each experience because they identify as gay, bisexual, or another sexual minority. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (about every day). For RADAR, investigators chose to administer nine items from two subscales: seven items from the Anti-Gay Attitudes and Expression subscale (e.g., “You heard someone say ‘that’s so gay’ in a negative way”) and two items from the Denial of Homosexuality subscale (e.g., “You were told that being gay is just a phase”). Items are averaged into a single score, with higher scores indicating a greater frequency of experiencing sexual orientation microaggressions (Time 1 α = .87). The measure showed convergent, criterion-related, and discriminant validity in two diverse samples of LGBTQ youth (Swann et al., 2016).

Internalized Stigma.

Internalized stigma was measured using 8 items from a 22-item adapted and validated scale (Puckett et al., 2017). The scale was developed using five items from the Homosexual Attitudes Inventory (Nungesser, 1983), which were adapted to be more interpretable for a youth population. Next, 17 items were added to the scale to capture a broader conceptualization of internalized stigma based on work of Ramirez-Valles, Kuhns, Campbell, and Diaz (2010). Based on recommendations from Puckett and colleagues (2017), the current study administered the 8 item Desire to be Straight subscale (e.g., “Sometimes I think that if I were straight, I would probably be happier”). Participants are instructed the following: “We are interested in how you feel about the following statements. For each statement, please indicate how much you agree or disagree.” No time frame is specified. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Items are averaged into a single score, with a higher scores indicating a higher level of internalized stigma (Time 1 α = .89). The measure showed convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity in a sample of YMSM (Puckett et al., 2017).

Rumination.

Rumination was measured using the 10-item version of The Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991), developed and psychometrically tested by Treynor, Gonzalez, and Nolen-Hoeksema (2003). Participants are instructed to report how often they think or do each item when they are feeling down, sad, or depressed (e.g., “Go away by yourself and think about why you feel this way”). No time frame is specified. Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). Items were summed into a single score, with higher scores reflecting higher frequency of ruminative tendencies. The RRS showed good psychometric properties in a randomly-selected, community sample of adults (Treynor et al., 2003). Previous research has shown that the RRS has high internal consistency (α = .89) and high test retest reliability (r = .80 over 5 months; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991). The internal reliability of this measure at Time 2 was high at in the present study (α = .91).

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Depression – Short Form 8a.

The PROMIS Depression – Short Form 8a is an 8-item instrument that assesses self-reported negative mood (i.e., sadness, guilt), views of self (i.e., self-criticism, worthlessness), social cognition (i.e., loneliness, interpersonal alienation), and decreased positive affect and engagement (i.e., loss of interest, meaning, and purpose). Participants are instructed to report how frequently they experienced these feelings in the past seven days. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Raw scores are calculated by summing item scores, multiplying by the total number of items, and dividing by number of answered items. The PROMIS Short Form 8a showed strong psychometric properties in a sample of MSM (Kaat, Newcomb, Ryan, & Mustanski, 2017). The internal reliability of this measure was high at each time point (α = .95 for all time points).

Analytic Approach

Prior to conducting mediation analyses, we examined bivariate correlations to explore concurrent and prospective associations among victimization, microaggressions, internalized stigma, rumination, and depression at each time point (i.e., baseline, 6- and 12-month follow-up). Next, mediation analyses were conducted in Mplus version 7.31 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015). Within this analytic sample, 6.7% of scale scores were missing. Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation was used to handle missing data. Little’s MCAR test showed that data were missing at random; Enders and Bandalos (2001) showed that FIML performed equally well handling data that were missing at random as with data that were missing completely at random. We found no significant differences in the likelihood of missing data based on age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, or gender identity.

We first tested the main effects of all predictor variables at Time 1 on depression at Time 3, controlling for depression at Time 1. We then conducted a path analysis to test the longitudinal mediation of victimization (Time 1), microaggressions (Time 1), internalized stigma (Time 1), and depression (Time 3) by rumination (Time 2). This approach allows for the simultaneous testing of multiple linear regressions and the computation of both direct and indirect effects and their corresponding standard errors. Depression at Time 1 was controlled for in the tests of direct effects of the three minority stress variables on depression at Time 3. Depression at Time 2 was controlled for in the test of the effect of rumination at Time 2 on depression at Time 3. In the RADAR cohort study, the RRS was not administered at Time 1 or Time 3; thus, these data were not available and rumination at Time 1 could not be controlled for in the path model. However, previous studies have shown that rumination is stable over periods of time comparable to those used in the present study (Just & Alloy, 1997; Kuehner & Weber, 1999; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema, Parker, & Larson, 1994); thus, there is less of a need to control for differences in rumination between Time 1 and Time 2, as these differences would be expected to be minimal.

Results

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among the constructs of interest are presented in Table 1. Statistically significant concurrent positive correlations were found among all three minority stress variables at all three time points, with the exception of the correlation between victimization and internalized stigma at Time 2. In addition, significant positive correlations were found between the three minority stress variables and concurrent rumination, and between concurrent rumination and depression, at Time 2 (the only time point for which rumination data were available). Concurrent correlations between minority stress variables and depression were positive and significant at all time points. Lastly, significant positive correlations were found between each minority stress variable at Time 1 and rumination at Time 2, and between rumination at Time 2 and depression at Time 3.

Table 1.

Bivariate Correlations and Descriptive Statistics for All Variables at All Time Points

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Victimization (T1) | |||||||||||||

| 2. Victimization (T2) | .44** | ||||||||||||

| 3. Victimization (T3) | .50** | .37** | |||||||||||

| 4. Microaggressions (T1) | .39** | .30** | .27** | ||||||||||

| 5. Microaggressions (T2) | .25** | .34** | .18** | .52** | |||||||||

| 6. Microaggressions (T3) | .31** | .31** | .27** | .58** | .57** | ||||||||

| 7. Internalized stigma (T1) | .11** | .09** | .09** | .26** | .18** | .20** | |||||||

| 8. Internalized stigma (T2) | .00 | .07 | .01 | .12* | .18** | .18** | .74** | ||||||

| 9. Internalized stigma (T3) | .05 | .05 | .09** | .13** | .16** | .23** | .69** | .78** | |||||

| 10. Rumination (T2) | .12** | .16** | .12** | .15** | .29** | .18** | .16** | .19** | .18** | ||||

| 11. Depression (T1) | .22** | .14** | .18** | .26** | .16** | .13** | .25** | .11* | .13** | .44** | |||

| 12. Depression (T2) | .09** | .11** | .13** | .07* | .18** | .11** | .14** | .20** | .15** | .58** | .56** | ||

| 13. Depression (T3) | .08* | .03 | .15** | .08* | .13** | .12** | .12** | .13* | .22** | .44** | .47** | .59** | |

| M | .22 | .13 | .12 | 2.01 | 1.79 | 1.75 | 1.74 | 1.64 | 1.56 | 19.40 | 15.71 | 14.19 | 14.03 |

| SD | .49 | .35 | .35 | .83 | .72 | .72 | .69 | .64 | .61 | 7.11 | 7.52 | 6.96 | 7.22 |

Note. T1-T3 = Time 1 to Time 3. Rumination data were collected only at T2, thus, Rumination at T1 and T3 are not included.

p < .05.

p < .01.

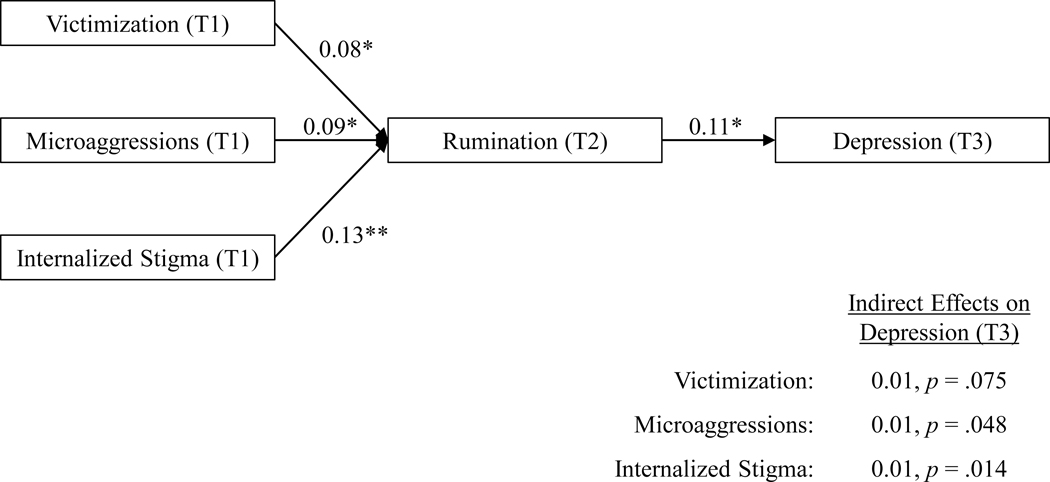

Main effects of victimization (B = −.01, SE = .03, p = .88), microaggressions (B = −.04, SE = .03, p = .25), and internalized stigma (B = .02, SE = .03, p = .43) at Time 1 on depression at Time 3, controlling for depression at Time 1, were not significant. Figure 1 presents results for the path model to test the longitudinal associations of victimization, microaggressions, internalized stigma, and depression, mediated by rumination. As hypothesized, all minority stress variables at Time 1 significantly predicted increased rumination at Time 2, which, in turn, significantly predicted higher levels of depression at Time 3, all with small effect sizes (Cohen, 1988). Direct effects of minority stress variables at Time 1 on depression at Time 3 in the mediation path model were not significant. Tests of the indirect effects showed microaggressions and internalized stigma at Time 1 had significant positive indirect effects on depression at Time 3, and victimization at Time 1 did not have a significant indirect effect on depression at Time 3 (see Figure 1). Given that this sample was composed of YMSM and a small group of YTW, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we removed the YTW in order to test for model robustness. We found that the pattern of results remained the same in the sample of YMSM only.

Figure 1.

The model above displays the results of the mediation analysis using standardized path coefficients. T1-T3 = Time 1-Time 3. Depression at Time 1 was controlled for in tests of direct effects of minority stress variables on depression; Depression at Time 2 was controlled for in the test of the effect of rumination at Time 2 on Depression at Time 3. For clarity of presentation, direct effects victimization (B= −.01, SE= .03, p= .78), microaggressions(B= −.01, SE= .03, p= .71), and internalized stigma (B= .01, SE= .03, p= .68) at Time 1 on depression at Time 3 are not depicted. *p< .05. **p< .001.

Discussion

The present study expanded upon existing literature on minority stress (Meyer, 2003) and psychological mediation frameworks (Hatzenbuehler, 2009) by testing longitudinal associations of victimization, microaggressions, internalized stigma, and depression, mediated by rumination, in a sample of YMSM and YTW. Results showed that rumination mediated the association of distal (i.e., victimization and microaggressions) and proximal (i.e., internalized stigma) minority stressors and depression. Those who had more frequent experiences of victimization and microaggressions and higher levels of internalized stigma at their baseline assessment experienced more rumination at 6-month follow-up, and, in turn, experienced greater depressive symptoms at 1-year follow-up. This is consistent with previous cross-sectional and daily diary studies showing that discrimination experiences, including victimization and sexual orientation microaggressions, and internalized stigma, were associated with rumination, which, in turn, was associated with increased psychological distress (Hatzenbuehler, Dovidio, et al., 2009; Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, et al., 2009; Kaufman et al., 2017; Liao et al., 2015; Szymanski et al., 2014; Timmins et al., 2019).

Findings of this study fill gaps left by previous cross-sectional studies by meeting a critical assumption of mediation models: namely, that these processes unfold over time (MacKinnon, 2008). Unfortunately, mediation continues to be tested using cross-sectional data analyses, despite studies showing that this creates a potential for misrepresentation of longitudinal processes (O’Laughlin et al., 2018). This study’s use of longitudinal data, with intervals between the predictor, mediator, and outcome variables, enables us to draw stronger conclusions regarding rumination as the mechanism whereby minority stress processes lead to increased depressive symptoms. This study is among the first to indicate that, over time, YMSM and YTW who experience more frequent victimization and microaggressions related to their sexual orientation then experience increased tendencies toward repetitive focus on the distress that those experiences cause; focusing on this distress, in turn, exacerbates psychological distress, leading to the development of symptoms of depression (Morrison & O’Connor, 2005; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008; Rottenberg et al., 2002).

Another novel aspect of this study is that we tested a single model with three simultaneous mediating effects. Thus, the findings indicate that victimization, microaggressions, and internalized stigma were each significant, unique, and positive predictors of rumination among YMSM and YTW. These results support tenets of minority stress theory (Meyer, 2003) and the psychological mediation framework (Hatzenbuehler, 2009) that distal and proximal minority stressors uniquely contribute to mental health outcomes. Previous cross-sectional studies have used this multivariate approach to test rumination as a mediator of distal and proximal minority stressors simultaneously (e.g., Szymanski et al., 2014). The findings of this longitudinal mediation study build upon this research by showing that these three minority stress variables contribute to depressive symptoms via rumination in a process that unfolds over time, which cannot be shown using cross-sectional data (MacKinnon, 2008; O’Laughlin et al., 2018).

It is notable that the effects of minority stress experiences predicted rumination six months later; this gives an indication of the long-lasting impacts of these stigmatizing events on the wellbeing of SGM individuals. Experiences of distal minority stressors (e.g., victimization and microaggressions) may engender increased hypervigilance, or attentional focus on one’s external environments and internal states (Major & O’Brien, 2005; Mays et al., 2007; Mendoza-Denton et al., 2002), specifically, thoughts and anxiety related to both past and future potential experiences of discrimination and rejection (Meyer, 2003). This hypervigilance may be chronic, and continue to manifest as a component of rumination long after the occurrence of these stigma-related experiences. Proximal minority stressors (e.g., internalized stigma) are proposed to have an effect on rumination because incorporating negative societal attitudes into one’s perception of themselves may lead to cognitive dissonance, because these negative attitudes conflict with their core identities (Festinger, 1962; Reilly & Rudd, 2006). Attempting to resolve this conflict may lead to a repetitive focus on the distress that it causes (Szymanski et al., 2014). Wrestling with a conflict around something as meaningful as one’s identity is also likely to have a chronic, lasting impact on wellbeing.

Main effects of minority stress variables at Time 1 on depression at Time 3 were not significant, indicating that victimization, microaggressions, and internalized stigma at baseline were not associated with depressive symptoms one year later. The causal steps approach to testing mediation, popularized by Baron and Kenny (1986), contains within it an assumption that the independent variable should have a significant effect on the dependent variable. However, Baron and Kenny’s (1986) approach has been criticized on multiple grounds, including the requirement that there is a significant “effect to be mediated,” and statisticians have argued that all that is required to establish mediation is that the indirect effect be significant (Zhao, Lynch Jr, & Chen, 2010). Thus, we were not deterred from testing the mediating effect of rumination after finding that the main effects of minority stress variables on depression were not significant. In this case, it may be that that the yearlong interval was too long to see the effect of minority stressors on depression; rather, minority stressors may only impact depression one year later via an increase in rumination.

Results of this study should be interpreted in light of its limitations. First, we were unable to control for rumination at Time 1, which would have enabled us to account for the effects of baseline rumination on subsequent rumination and depression and have more certainty about the unique effects of minority stress variables. Future longitudinal research on the psychological mediation framework that measures rumination at multiple time points could provide more sound evidence of the associations found in this study. Additionally, in line with research showing that stressful life events and internalizing psychopathology have a bidirectional relationship (Jenness, Peverill, King, Hankin, & McLaughlin, 2019), future research should examine how minority stressors and depression mutually influence each other, perhaps via rumination. Another limitation is our exclusive use of self-report measures to assess minority stress experiences, rumination, and depression. Future research could improve on this limitation by using the sexual orientation Implicit Association Test to assess implicit self-stigmatization (Hatzenbuehler, Dovidio, et al., 2009), experimental manipulation of microaggressions (Lilienfeld, 2017; West, 2019), or clinician-administered measures of depression, such as the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (First, Williams, Karg, & Spitzer, 2015).

An additional limitation is that participants were from a large, community-based cohort study of YMSM and YTW located in Chicago. This sample may not be representative of SGM individuals who do not live in large, urban environments, and thus are less connected to SGM communities and may have more frequent experiences of victimization and/or microaggressions and higher levels of internalized stigma. Future research conducted with a sample of SGM individuals with a wider range of minority stress experiences would complement the present study and add to literature on minority stress theory and the psychological mediation framework. This study was also limited in that it focused only on SGM individuals who were assigned male at birth, and we were unable to compare these results by sex assigned at birth, or make any generalizations about these results to those who are assigned female at birth. We also did not have enough YTW in this sample to have the statistical power to make comparisons based on gender identity, though removing YTW from the analyses resulted in the same pattern of results. Future research with diverse samples of SGM in regards to gender identity and sex assigned at birth would allow us to have a greater understanding of the roles of rumination in the development of depressive symptoms in this population.

Despite the study’s limitations, its results have important implications for clinical practice with SGM individuals. Depression among SGM populations is widespread (Borgogna et al., 2019; Cochran et al., 2003; Marshal et al., 2013; Mills et al., 2004; Mustanski et al., 2010), and is comorbid with substance abuse (Sérráno & Wiswell, 2018; Weber & Dodge, 2018), suicidal ideation (Perez-Brumer et al., 2017), and suicide attempts (Peter & Taylor, 2014). As rumination appears to be a process whereby experiences of minority stress manifest into depressive symptoms, decreasing the utilization of rumination as a maladaptive coping strategy should be a priority for interventions to reduce depression among SGM individuals. ESTEEM, a 10-session LGB-affirmative cognitive-behavioral intervention for young adult gay and bisexual men, aims to reduce the impact of minority stressors on mental health, in part by using cognitive restructuring to decrease rumination (Pachankis, 2014). Results of a randomized controlled trial of ESTEEM showed that it decreased rumination from pre- to post-treatment (Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler, Rendina, Safren, & Parsons, 2015), which shows promise for continued development of interventions to reduce mental health disparities in SGM populations. Future longitudinal research on the mediating role of rumination in the development of depression for those who experience chronic minority stressors can further inform interventions to address this health disparity in SGM populations.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (U01DA036939) and approved by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board (STU00087614).

Some of the hypotheses and results described in this manuscript were presented in a poster at the annual conference of the American Psychological Association in Chicago, IL on August 8, 2019. The poster tested the effect of LGBT victimization and perceived stress on depression, mediated by rumination.

References

- Baron RM, & Kenny DA (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkett M, Newcomb ME, & Mustanski B. (2015). Does it get better? A longitudinal analysis of psychological distress and victimization in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56, 280–285. doi:doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissonette D, & Szymanski DM (2019). Minority stress and LGBQ college students’ depression: Roles of peer group and involvement. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 6, 308–317. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000332 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borgogna NC, McDermott RC, Aita SL, & Kridel MM (2019). Anxiety and depression across gender and sexual minorities: Implications for transgender, gender nonconforming, pansexual, demisexual, asexual, queer, and questioning individuals. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 6, 54–63. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chesir-Teran D, & Hughes D. (2009). Heterosexism in high school and victimization among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 963–975. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9364-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran SD, Sullivan JG, & Mays VM (2003). Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress, and mental health services use among LGB adults in the United States. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 71, 53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (Second ed). Hillsdale, New Jersey: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR (1992). Lesbian and gay male undergraduates’ experiences of harassment and fear on campus. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 7. doi: 10.1177/088626092007003007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’Augelli AR, Pilkington NW, & Hershberger SL (2002). Incidence and mental health impact of sexual orientation victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths in high school. School Psychology Quarterly, 17, 148–167. doi:DOI 10.1521/scpq.17.2.148.20854 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dyar C, & London B. (2018). Bipositive events: Associations with proximal stressors, bisexual identity, and mental health among bisexual cisgender women. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 5, 204–219. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000281 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, & Bandalos DL (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling-a Multidisciplinary Journal, 8, 430–457. doi: 10.1207/S15328007sem0803_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. (1962). A theory of cognitive dissonance (Vol. 2): Stanford university press. [Google Scholar]

- First M, Williams J, Karg R, & Spitzer R. (2015). Structured clinical interview for DSM-5—Research version (SCID-5 for DSM-5, research version; SCID-5-RV). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 1–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ (2001). Emotion regulation in adulthood: Timing is everything. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 214–219. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.00152 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall WJ (2018). Psychosocial risk and protective factors for depression among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer youth: A systematic review. Journal of Homosexuality, 65, 263–316. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2017.1317467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Dovidio JF, Nolen-Hoeksema S, & Phills CE (2009). An implicit measure of anti-gay attitudes: Prospective associations with emotion regulation strategies and psychological distress. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 1316–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, & Nolen-Hoeksema S. (2008). Emotion regulation and internalizing symptoms in a longitudinal study of sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 1270–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, & Dovidio JF (2009). How does stigma ‘get under the skin’?: The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychological Science, 20, 1282–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenness JL, Peverill M, King KM, Hankin BL, & McLaughlin KA (2019). Dynamic associations between stressful life events and adolescent internalizing psychopathology in a multiwave longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 128, 596–609. doi: 10.1037/abn000045010.1037/abn0000450.supp (Supplemental) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just N, & Alloy LB (1997). The response styles theory of depression: Tests and an extension of the theory. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106, 221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaat AJ, Newcomb ME, Ryan DT, & Mustanski B. (2017). Expanding a common metric for depression reporting: Linking two scales to PROMIS((R)) depression. Quality of Life Research, 26, 1119–1128. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1450-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Olsen EO, McManus T, Harris WA, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, . . . Zaza S. (2016). Sexual identity, sex of sexual contacts, and health-related behaviors among students in grades 9–12 - United States and selected sites, 2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Surveillance Summaries, 65, 1–202. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6509a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman TM, Baams L, & Dubas JS (2017). Microaggressions and depressive symptoms in sexual minority youth: The roles of rumination and social support. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 4, 184. [Google Scholar]

- Kuehner C, & Weber I. (1999). Responses to depression in unipolar depressed patients: An investigation of Nolen-Hoeksema’s response styles theory. Psychological Medicine, 29, 1323–1333. doi: 10.1017/S0033291799001282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao KY-H, Kashubeck-West S, Weng C-Y, & Deitz C. (2015). Testing a mediation framework for the link between perceived discrimination and psychological distress among sexual minority individuals. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62, 226–241. doi: 10.1037/cou0000064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld SO (2017). Microaggressions: Strong claims, inadequate evidence. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12, 138–169. doi: 10.1177/1745691616659391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Tucker KL, Caldwell ND, & Berg K. (1999). Why ruminators are poor problem solvers: Clues from the phenomenology of dysphoric rumination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1041–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP (2008). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Major B, & O’Brien LT (2005). The social psychology of stigma. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 393–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Dermody SS, Cheong J, Burton CM, Friedman MS, Aranda F, & Hughes TL (2013). Trajectories of depressive symptoms and suicidality among heterosexual and sexual minority youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42, 1243–1256. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9970-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD, & Barnes NW (2007). Race, race-based discrimination, and health outcomes among African Americans. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 201–225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Denton R, Downey G, Purdie VJ, Davis A, & Pietrzak J. (2002). Sensitivity to status-based rejection: implications for African American students’ college experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills TC, Paul J, Stall R, Pollack L, Canchola J, Chang YJ, . . . Catania JA (2004). Distress and depression in men who have sex with men: the Urban Men’s Health Study. Am J Psychiatry, 161, 278–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison R, & O’Connor RC (2005). Predicting Psychological Distress in College Students: The Role of Rumination and Stress. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61, 447–460. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Andrews R, & Puckett JA (2016). The effects of cumulative victimization on mental health among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Public Health, 106, 527–533. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Garofalo R, & Emerson EM (2010). Mental health disorders, psychological distress, and suicidality in a diverse sample of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youths. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 2426–2432. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.178319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Ryan DT, Hayford C, Phillips G 2nd, Newcomb ME., & Smith JD. (2018). Geographic and individual asociations with PrEP stigma: Results from the RADAR cohort of diverse young men who have sex with men and transgender women. AIDS and Behavior, 22, 3044–3056. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2159-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998-2015). Mplus User’s Guide. Seventh Edition In. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nadal KL, Rivera DP, & Corpus MJH (2010). Sexual orientation and transgender microagressions: Implications for mental health and counseling In Sue DW (Ed.), Microaggressions and marginality: Manifestation, dynamics, and impact. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Nadal KL, Whitman CN, Davis LS, Erazo T, & Davidoff KC (2016). Microaggressions toward lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and genderqueer people: A review of the literature. The Journal of Sex Research, 53, 488–508. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2016.1142495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal KL, Wong Y, Issa M-A, Meterko V, Leon J, & Wideman M. (2011). Sexual orientation microaggressions: Processes and coping mechanisms for lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 5, 21–46. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb ME, & Mustanski B. (2010). Internalized homophobia and internalizing mental health problems: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 504–511. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, & Morrow J. (1991). A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 115–121. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Parker LE, & Larson J. (1994). Ruminative coping with depressed mood following loss. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 92–104. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.67.1.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, & Lyubomirsky S. (2008). Rethinking Rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 400–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nungesser LG (1983). Homosexual acts, actors, and identities. New York, NY: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- O’Laughlin KD, Martin MJ, & Ferrer E. (2018). Cross-sectional analysis of longitudinal mediation processes. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 53, 375–402. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2018.1454822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE (2014). Uncovering clinical principles and techniques to address minority stress, mental health, and related health risks among gay and bisexual men. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 21, 313–330. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Rendina HJ, Safren SA, & Parsons JT (2015). LGB-affirmative cognitive-behavioral therapy for young adult gay and bisexual men: A randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic minority stress approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83, 875–889. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Sullivan TJ, Feinstein BA, & Newcomb ME (2018). Young adult gay and bisexual men’s stigma experiences and mental health: An 8-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 54, 1381–1393. doi: 10.1037/dev0000518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Brumer A, Day JK, Russell ST, & Hatzenbuehler ML (2017). Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation among transgender youth in California: Findings from a representative, population-based sample of high school students. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56, 739–746. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter T, & Taylor C. (2014). Buried above ground: A university-based study of risk/protective factors for suicidality among sexual minority youth in Canada. Journal of LGBT Youth, 11, 125–149. doi: 10.1080/19361653.2014.878563 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkington NW, & D’Augelli AR (1995). Victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth in community settings. Journal of Community Psychology, 23, 34–56. [Google Scholar]

- Puckett JA, Newcomb ME, Ryan DT, Swann G, Garofalo R, & Mustanski B. (2017). Internalized homophobia and perceived stigma: A validation study of stigma measures in a sample of young men who have sex with men. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 14, 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s13178-016-0258-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Valles J, Kuhns LM, Campbell RT, & Diaz RM (2010). Social integration and health: community involvement, stigmatized identities, and sexual risk in Latino sexual minorities. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51, 30–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly A, & Rudd NA (2006). Is internalized homonegativity related to body image? Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 35, 58–73. [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg J, Kasch KL, Gross JJ, & Gotlib IH (2002). Sadness and amusement reactivity differentially predict concurrent and prospective functioning in major depressive disorder. Emotion, 2, 135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salim S, Robinson M, & Flanders CE (2019). Bisexual women’s experiences of microaggressions and microaffirmations and their relation to mental health. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 6, 336–346. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sérráno BC, & Wiswell AS (2018). Drug and alcohol abuse and addiction in the LGBT community: Factors impacting rates of use and abuse In Stewart C. (Ed.), Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender Americans at risk: Problems and solutions: Adults, Generation X, and Generation Y., Vol. 2 (pp. 91–112). Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger/ABC-CLIO. [Google Scholar]

- Swann G, Minshew R, Newcomb ME, & Mustanski B. (2016). Validation of the Sexual Orientation Microaggression Inventory in two diverse samples of LGBTQ youth. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45, 1289–1298. doi: 10.1007/s10508-016-0718-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski DM, Dunn TL, & Ikizler AS (2014). Multiple minority stressors and psychological distress among sexual minority women: The roles of rumination and maladaptive coping. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1, 412–421. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Timmins L, Rimes KA, & Rahman Q. (2019). Minority stressors, rumination, and psychological distress in lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treynor W, Gonzalez R, & Nolen-Hoeksema S. (2003). Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27, 247–259. doi: 10.1023/A:1023910315561 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Ewing BA, Espelage DL, Green HD Jr., de la Haye K, & Pollard MS (2016). Longitudinal associations of homophobic name-calling victimization with psychological distress and alcohol use during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59, 110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber G, & Dodge A. (2018). Substance use among gender and sexual minority youth and adults In Smalley KB, Warren JC, & Barefoot KN (Eds.), LGBT health: Meeting the needs of gender and sexual minorities. (pp. 199–213). New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- West K. (2019). Testing hypersensitive responses: Ethnic minorities are not more sensitive to microaggressions, they just experience them more frequently. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45, 1619–1632. doi: 10.1177/0146167219838790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Lynch JG Jr, & Chen Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar]