Abstract

Objective

The goal of this study was to test the hypothesis that diabetes self-efficacy mediates the relationship between impulse control and type 1 diabetes (T1D) management from ages 8 to 18 years, using multilevel modeling.

Methods

Participants included 117 youth with T1D and their parents. Youth (aged 8–16 years at baseline) and parents were assessed 5 times over 2 years. Using a cohort sequential design, we first estimated the growth trajectory of adherence from age 8 to 18 years, then specified a multilevel mediation model using impulse control as the main predictor, diabetes self-efficacy as the mediator, and changes in adherence (both within- and between-individuals) as the outcome.

Results

According to youth-reported adherence only, self-efficacy partially mediated the within-person effect of impulse control on adherence. On occasions when youth reported increases in impulse control, they tended to report higher adherence, and this was, in part, due to increases in youths’ perceived self-efficacy. Self-efficacy accounted for approximately 21% of the within-person relationship between impulse control and youth-reported adherence. There was no association between impulse control and adherence between-individuals. Impulse control and self-efficacy were not related to parent-reported adherence.

Conclusion

Environments that enrich youth with confidence in their own diabetes-related abilities may benefit self-care behaviors in youth with T1D, but such increases in youths’ perceived competence do not fully account for, or override, the behavioral benefits of impulse control. Efforts to improve adherence in youth with T1D will benefit from consideration of both impulse control and self-efficacy.

Keywords: adherence, chronic illness, diabetes, longitudinal research, psychosocial functioning

Introduction

Management of type 1 diabetes (T1D), which entails checking blood glucose levels several times per day, dosing insulin, monitoring food intake, exercising, and responding to high or low blood glucose, requires considerable daily effort and can be particularly challenging in adolescence compared with childhood and adulthood (King, Berg, Butner, Butler, & Wiebe, 2014; Wood et al., 2013). From a developmental perspective, a factor that may contribute to the challenges of T1D management in adolescence is that the regulatory skills required for successful self-care—which include planning ahead, monitoring emotions and behaviors, and controlling the impulse to give into immediate rewards—are not fully mature (Casey, 2015). Although many adolescents are capable of self-regulation and impulse control, doing so consistently can be difficult, especially in the context of competing pressures and demands (Shulman et al., 2016).

Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies demonstrate that adolescents with good self-regulation engage in more self-care behaviors (and have better glycemic control; e.g., Vaid, Lansing, & Stanger, 2018) compared to adolescents with low self-regulation (e.g., Bagner, Williams, Geffken, Soilverstein, & Storch, 2007; Berg et al., 2014; Duke & Harris, 2014; Miller et al., 2013; Wiebe, Berg, Mello, & Kelly, 2018). In our own prior longitudinal work, we found that improvements in impulse control, within individuals, coincided with increases in adherence (Silva & Miller, 2019); improvements in impulse control appeared to be particularly protective as maturing youth take on more responsibility for T1D management from late childhood to late adolescence (Silva & Miller, 2019). Several qualitative studies of adolescents with T1D also illustrate the ways in which adolescents’ tendency to favor immediate outcomes may interfere with T1D management, particularly in social or emotionally stimulating contexts (e.g., “If you’re going to a movie to eat popcorn, you don’t want to be like hold on let me check my blood” [Babler & Strickland, 2015, p. 655]; “When I am out with my friends a lot of times I’m not as good about checking the things I need to do” [Hanna & Guthrie, 2000, p. 170]).

Developmental studies demonstrate that impulse control is a skill that develops across adolescence and into early adulthood (Harden & Tucker-Drob, 2011; Shulman, Harden, Chein, & Steinberg, 2015). As impulse control matures, it may be easier to stop a fun activity to execute important illness-related tasks (Silva & Miller, 2019). Nonetheless, how exactly impulse control facilitates T1D management in developing youth remains an understudied subject.

Since impulse control is a skill that matures over time, maturational gains in impulse control may set the developmental context for other psychological processes to unfold that, in turn, facilitate desirable health behaviors in maturing youth. One such process that may unfold with improvements in impulse control is self-efficacy. Self-efficacy refers to individuals’ perceived confidence in their abilities to perform self-care behaviors in challenging or affect-laden situations—for example, checking blood glucose levels even when engaged in another task, exercising when one does not want to, and completing other diabetes-related tasks despite feeling overwhelmed (Iannotti et al., 2006). Several cross-sectional and longitudinal studies show that self-efficacy is positively associated with T1D management in adolescence (Berg et al., 2011; Johnston-Brooks, Lewis, & Garg, 2002; Littlefield et al., 1992; Ott et al., 2000; Wiebe et al., 2014). Moreover, and similar to impulse control (Silva & Miller, 2019), there is evidence from a longitudinal study of adolescents that improvements in self-efficacy are protective against age-related declines in adherence as youth take on responsibility for self-managing their diabetes (Wiebe et al., 2014). Thus, both impulse control and self-efficacy are known to be independently associated with adherence in youth with T1D, and both constructs have been shown to moderate the relationship between treatment responsibility and T1D management in adolescence.

Social cognitive theory considers impulse control and self-efficacy important person-level factors that influence behaviors and posits that belief in one’s self-efficacy is a common pathway through which psychosocial variables affect health behaviors and functioning (Bandura, 2004). Although several studies point to self-efficacy as a mediator of the relationship between impulsivity and adolescent risk behaviors, such as substance use (e.g., Hayaki et al., 2011; Patton et al., 2018), few studies have examined the role of these constructs in diabetes management within the same sample. To our knowledge, only one prior cross-sectional study of late adolescents with T1D has explored impulse control and self-efficacy and suggested that self-efficacy is a mechanism via which impulse control is related to individual differences in youth adherence (Stupiansky et al., 2013). In that study, adolescents with higher impulse control tended to exhibit better self-management, and this association was largely explained by individuals’ level of self-efficacy. Based on this finding, the study authors suggested that diabetes management in adolescence could be amenable to intervention through self-efficacy (Stupiansky et al., 2013). However, further longitudinal research is necessary to substantiate such conclusions and to better inform interventions aimed at improving T1D management in adolescence.

Using multilevel modeling, the present study—based on a secondary analysis of an existing dataset—expands existing cross-sectional research by examining the longitudinal relationship between impulse control, self-efficacy, and diabetes adherence in a sample of youth (ages 8–16 years) with T1D. Specifically, the goal of this study was to test the hypothesis that diabetes self-efficacy mediates the relationship between impulse control and diabetes management from late childhood to late adolescence, both between- and within-individuals. Within-person estimates (level 1) are based on repeated (time-varying) measures and represent the extent to which time-specific changes in the predictor(s) (i.e., impulse control and self-efficacy) relate to time-specific changes in the outcome (i.e., adherence) within each individual. Between-person estimates (level 2) are based on sample averages and represent the extent to which individual differences in impulse control and self-efficacy are related to individual differences in adherence. By distinguishing between- and within-person effects, we are able to examine both the extent to which cumulative increases in impulse control contribute to increases in adherence (via changes in self-efficacy within individuals) and the extent to which youths’ baseline levels of impulse control contribute to individual differences in adherence (via self-efficacy). At both the between- and within-person levels, we hypothesized that impulse control would be associated with more diabetes self-care behaviors, at least in part, because increases in impulse control may enable youth to feel more confident and capable of performing diabetes-related tasks.

While we acknowledge that impulse control and self-efficacy may be important predictors of glycemic control in adolescence, we did not include hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c, a measure of glycemic control) as an outcome in this analysis because we were primarily interested in self-reported behavior, not clinical outcomes. However, HbA1c was included as a covariate in all the analyses conducted and reported here.

Methods

This study is based on secondary analysis of data from a larger longitudinal study designed to examine predictors and outcomes of decision-making involvement in a sample of youth with T1D or cystic fibrosis (Miller & Jawad, 2019). The study used a cohort sequential design, which involves the examination of different age cohorts over the same time period, and allows the combination of multiple short-term longitudinal data points to estimate a single long-term growth pattern using growth curve modeling (Miyazaki & Raudenbush, 2000). Nine age cohorts (8-to-16-year-olds) were assessed at baseline and every six months for two years (for five total assessments). The number of participants in each age cohort varied at baseline: 8 years (n = 6), 9 years (n = 11), 10 years (n = 18), 11 years (n = 13), 12 years (n = 12), 13 years (n = 10), 14 years (n = 16), 15 years (n = 18), and 16 years (n = 13). The nine age cohorts were linked to form a common developmental trajectory spanning ages 8–18. Although the larger study included youth with T1D or cystic fibrosis, the current study describes the procedures, measures, sample, and data from youth with T1D and their parents only.

Participants and Procedures

Parents and youth were recruited from an endocrinology clinic at a tertiary children’s hospital in a large Northeastern city in the United States. All study procedures were in accordance with U.S. guidelines for the ethical conduct of human subject research and approved by the institutional review board. Participants were eligible if they were English-speaking, the parent was the biological or adoptive parent, and youth had been diagnosed with T1D for at least one year and lived with the parent at least 50% of the week. Youth were ineligible if they had developmental delay, past-year psychiatric hospitalization, or another life-threatening medical condition, unrelated to T1D, which required daily treatment for more than 6 months in the last year.

Five hundred sixteen potential families were identified through outpatient clinic lists and schedules. Of those identified, 48.3% (n = 249) could not be contacted, and 51.7% (n = 267) were reached by telephone. Of those who were contacted, 18.7% (n = 50) could not be reached again, 18.7% (n = 50) declined immediately, and the remaining 62.5% (n = 167) agreed to be screened for eligibility. Of the 167 families screened for eligibility, 9.6% (n = 16) were ineligible. Common reasons for ineligibility included that the child was diagnosed with T1D less than 1 year ago or had at least one other illness not related to T1D that required daily treatment for greater than 6 months of the last year. Of the 151 parent–child dyads that were eligible, 148 (98%) agreed to participate, but 10 (6.6%) could not be scheduled or reached again, 14 (9.3%) did not show up for their scheduled appointments, and 1 (0.7%) declined in person. Of the 123 (81%) dyads who consented and enrolled in the study, 4 (3.3%) did not complete Visit 1 and an additional two dyads (1.3%) were withdrawn from the study by the principal investigator after finding they no longer met eligibility criteria. The final sample included 117 parent–youth dyads. Chi-square and independent samples t-tests indicated that there were no significant differences found between these participants and those who were eligible but declined, could not be scheduled, or did not complete Visit 1 (n = 34) with respect to age, duration of diagnosis, child sex, child race, or child ethnicity (all ps > .20).

All data were collected via self-report questionnaires (some of which were completed by youth only and others were completed by both parents and youth). Research personnel read questionnaires to youth ages 8–10 years to promote comprehension.

Approximately 55% of youth in the sample were female, and the mean youth age at baseline was 12.87 (SD = 2.53). Overall, approximately 60% of the youth were non-Hispanic white (n = 69), 22% were non-Hispanic black (n = 25), 10% were Hispanic (n = 12), 5% were other (n = 7), and 1 youth was Asian. The majority (77%) of youth lived in two-parent households and had been living with T1D for approximately 5.63 years (SD = 3.53). At baseline, the mean HbA1c was 8.76% (SD = 1.49). Approximately 39% of the youth were using an insulin pump, 40% were on a basal-bolus regimen, and 21% were on a pre-mixed regimen (70/30).

Measures

Reliability was estimated separately for each variable at each time point. We report the range of reliability coefficients, as well as the intraclass correlations (ICC) across measurement waves to indicate within-subject reliability. Variable means and standard deviations (for each time point and age cohort) are reported in the Supplementary Table.

Impulse Control

At all visits, youth completed the eight-item impulse control subscale from the Weinberger Adjustment Inventory (Weinberger, 1997). Participants indicated how accurately a series of eight statements (e.g., “I stop and think things through before I act;” “I should try harder to control myself when I’m having fun” [reverse coded]) described them on a 5-point Likert-type scale (ranging from 1 = almost never to 5 = almost always). Scores were averaged across items such that higher scores indicate greater impulse control. Cronbach’s alphas across visits ranged from 0.76 to 0.84. The ICC was moderately high (0.70).

Diabetes Self-Efficacy

At visits 1, 3, and 5, youth completed the Diabetes Self-efficacy Scale (DSES), a 10-item measure to assess youth self-efficacy in managing illness-related emotions and procedures associated with the diabetes treatment regimen (Iannotti et al., 2006). Youth indicated how sure they felt (on a scale from 1 = not at all to 10 = completely sure) that they could do a series of 10 tasks including choosing healthy foods when they go out to eat, doing their blood sugar checks even when they are really busy, and taking care of their diabetes even when they feel overwhelmed. Scores were averaged across items such that higher scores indicate higher diabetes self-efficacy. Cronbach’s alphas across all visits ranged from 0.80 to 0.86. The ICC was 0.54.

Diabetes Adherence

At all visits, youth and parents completed the Self Care Inventory (La Greca, Follansbee, & Skyler, 1990), a 14-item measure to assess past-month adherence to multiple aspects of the diabetes treatment regimen (e.g., glucose testing, administering and adjusting insulin, eating regular snacks). Responses range from 1 (never do it) to 5 (always do this without fail). Scores were averaged across items such that higher scores indicate better adherence. Cronbach’s alphas across all visits ranged from 0.69 to 0.83 for youth report and 0.70 to 0.81 for parent report. The ICC was 0.95 and 0.63, for youth and parent report, respectively.

Although the main predictor (impulse control) and proposed mediator (self-efficacy) reflect youth-reported data, we used both youth and parent reports of adherence because a multi-informant approach is typically better than single-informant (De Los Reyes et al., 2015). Moreover, descriptive and preliminary analyses revealed few notable discrepancies between youth and parent reports of adherence. Overall, a significant reporter discrepancy was noted at Time 4 only (t (92) = 2.72, p = .008) and further investigation revealed that the discrepancy was driven by youth and parents in the 11-year-old cohort (t(10) = 2.90, p = .016).

Chart Review

During visits 1, 3, and 5, study staff completed a review of participants’ medical charts to obtain information regarding insulin regimen (pump, premixed 70/30, or basal-bolus) and hemoglobin A1C.

Attrition and Missing Data

Of the 117 dyads enrolled in the study, 78 completed all follow-up visits, 33 completed between 1 and 3 follow-up visits, and 6 did not complete any follow-up visits. Overall, there were 117 evaluable cases at visit 1, 97 at visit 2, 101 at visit 3, 97 at visit 4, and 96 at visit 5. There were no significant differences between participants who completed no follow-ups, 1–3 follow-ups, and all 5 follow-ups with respect to baseline age, demographics, or main variables analyzed in the present study (all ps > .05).

The amount of missing data was low and ranged from 1.3% to 2.6% for each study visit. Across study visits, two youth had missing data on impulse control and diabetes self-efficacy, one youth had missing data on self-reported adherence, and two youth had missing data on parents’ report of adherence. Youth with missing data on parents’ report of adherence had lower self-efficacy at baseline compared to youth without missing parent data (p < .05). No differences were found between youth with versus without missing data on self-reported adherence, impulse control, or self-efficacy (all ps > .05). Missing data were addressed using full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation.

Data Analysis

Since the current study was based on secondary data analysis, we ensured we had a sufficiently large sample size to achieve 80% power in the estimation of longitudinal mediation effects. Assuming an ICC of 0.90 (given the high ICC for child-reported adherence) and a study design of at least three observations per subject (since data on youth self-efficacy were collected at three-time points only), the estimated number of subjects required to achieve a medium-sized mediation affect is 73 (Pan, Liu, Miao, & Yuan, 2018). Based on these estimates, we concluded that the current sample size was sufficient to achieve 80% power in a longitudinal mediation analysis that treats all path coefficients as fixed-effects (i.e., model estimates were constrained to be equal across individuals).

Model Building

In the present analysis, we built on two previously described models that estimated age-related changes in child- and parent-reported adherence in the current study sample (Silva & Miller, 2019). These models were estimated using latent growth curve modeling, with age (8–18) as the marker of time, centered at the grand mean (13.77 years). The process for identifying potential covariates of changes in adherence is described in Silva & Miller (2019). For models estimating parent-reported adherence, no significant covariates were identified. Models estimating youth-reported adherence included baseline age, baseline adherence, race/ethnicity, and income as covariates at level 2 (to account for differences between individuals). In this analysis, we retained the previously identified level 2 covariates and, in addition, controlled for HbA1c at both level 1 (centered at baseline values) and level 2 (baseline values centered at the grand-mean) to estimate the total effect of impulse control on adherence. At level 1, impulse control was centered at participants’ baseline score so that the estimate represents within-person deviation, or cumulative change, from the first time point (Hoffman & Stawski, 2009). At level 2, baseline values of impulse control were grand-mean centered to reflect individual differences.

To test whether self-efficacy mediated the relationship between impulse control and adherence, we specified further a multilevel mediation model (Krull & MacKinnon, 2001; Preacher, Zyphur, & Zhang, 2010; Zhang, Zyphur, & Preacher, 2009), whereby the main predictor (i.e., impulse control) and mediator (i.e., self-efficacy) were entered simultaneously at level 1 and level 2. At level 1, both impulse control and self-efficacy were person-centered at individuals’ baseline value. We specified random intercepts and fixed slopes. At level 2, baseline values of impulse control and self-efficacy (centered at the grand-mean) were used to test mediation at the sample average (similar to cross-sectional estimates). Separate multilevel mediation models were run for parent and youth report of adherence, and all paths controlled for HbA1c at level 1 and level 2. Analyses were conducted in Mplus 7.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). The MODEL CONSTRAINT function was used to estimate the indirect effects of impulse control on adherence (via self-efficacy) at both levels. To estimate what proportion of the relationship between impulse control and adherence was accounted for by self-efficacy, we divided the coefficient capturing the indirect effect by the total effect coefficient, and then multiplied by 100.

Results

Youth-Reported Adherence

The total effects model revealed that impulse control was a significant positive predictor of within-person variability in youth-reported adherence (total effect at level 1: B = .14, SE = .03, p < .001), controlling for HbA1c. This finding indicated that on occasions when youth experienced increases in impulse control (relative to baseline), they exhibited concurrent increases in adherence. At the between-subjects level, impulse control was not a significant predictor of individual differences in overall adherence at age 13.77 (intercept: B = .04, SE = .03, p = .16), or rate of decline in adherence from ages 8–18 years (slope: B = −.001, SE = .01, p = .94), controlling for baseline HbA1c, baseline age, baseline adherence, race/ethnicity, and income.

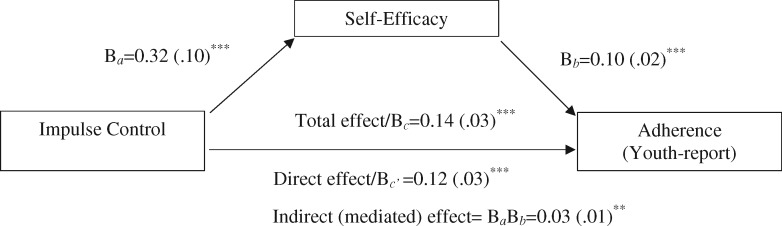

Results from the multilevel mediation model indicated a significant within-person relationship between impulse control and self-efficacy (Table I; level 1, a path: Ba=0.32, SE = 0.10, p < 0.001), suggesting that on occasions when youth reported increases in impulse control, they also reported increases in self-efficacy. Time-specific increases in self-efficacy were, in turn, associated with concurrent increases in adherence (level 1, b path: Bb=0.10, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001). Moreover, there was a significant indirect effect of impulse control on adherence via self-efficacy within individuals (Table I; B = 0.03, 95% CI = 0.01, 0.05, p = 0.005). The within-person effect of impulse control on adherence remained significant after accounting for associations with self-efficacy (level 1, c’ path: Bc’ = 0.12, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001), suggesting a partially mediated effect at level 1 (Figure 1). Specifically, self-efficacy accounted for 21% of the within-person association between impulse control and adherence.

Table I.

Results from Multilevel Mediation Models

| a path | b path | c’ path | Indirect effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impulse control→self-efficacy | Self-efficacy→ adherence | Impulse control→adherence, accounting for self-efficacy | (Ba*Bb) | |

| Youth-reported adherence | Ba (SE) | Bb (SE) | Bc’ (SE) | B [95% CI] |

| Level 1 | .32 (.10)**** | .10 (.02) **** | .12 (.03) **** | .03 [.01, .05]*** |

| Level 2 | .50 (.15) **** | .05 (.02)** | .03 (.03) | .03 [−.002, .05]* |

| Parent-reported adherence | ||||

| Level 1 | .32 (.10) **** | .01 (.02) | .01 (.03) | −.001 [−.02, .02] |

| Level 2 | .50 (.15) **** | −.002 (.02) | .02 (.03) | .004 [−.01, .01] |

Note. CI = confidence interval; SE = standard error.

p < 0.10.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Figure 1.

Self-efficacy partially mediated the within-person effect of impulse control on youth-reported adherence. Indirect (mediated) effect = BaBb = 0.03 (.01)**. Note. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

At level 2, there was a significant positive association between impulse control and self-efficacy (Table I; level 2, a path: Ba = 0.50, SE = 0.15, p = 0.001), suggesting that, on average, youth with higher impulse control at baseline also reported higher self-efficacy. There was also a positive association between self-efficacy and adherence (Table I; level 2, b path: Bb = 0.05, SE = 0.02, p = 0.03), suggesting that youth with higher self-efficacy at baseline reported higher adherence. However, self-efficacy did not mediate the association between impulse control and adherence at level 2 (B = 0.03, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = −0.002, 0.05, p = 0.07).

Parent-Reported Adherence

Impulse control was not associated with parents’ report of adherence at level 1 (Table I, c’ path: Bc’ =0.01, SE = 0.03, p = 0.67) or level 2 (Bc’ = 0.02, SE = 0.03, p = 0.48), controlling for HbA1c. Likewise, self-efficacy was not associated with parents’ report of adherence at level 1 (Table I, b path: Bb=0.01, SE = 0.02, p = 0.51) or level 2 (Bb = −0.002, SE = 0.02, p = 0.92), even after controlling for HbA1c. There was no evidence of a mediated effect between impulse control and parent-reported adherence via self-efficacy (Table I).

Discussion

In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that diabetes self-efficacy would mediate the relationship between impulse control and T1D management from late childhood to late adolescence using multilevel modeling. We found that at least some (21%) of the within-person association between regulatory ability (i.e., impulse control) and youth-reported adherence was accounted for by the degree to which youth felt confidence in their ability to carry out diabetes-related tasks. This pattern of findings did not hold for parent-reported adherence, which was surprising given the lack of reporter discrepancy in the current sample.

Contrary to prior findings (Stupiansky et al., 2013), we did not find evidence that, on average, youth with higher impulse control reported higher adherence, neither directly nor indirectly through self-efficacy. Differences in methodology, including study design and analytic approach, may account for the discrepancy in findings. Despite the fact that both studies were based on secondary analysis and relied on self-reported data, our study sample was relatively younger and included a wider age range (8–16 years, mean = 12.9) compared to the study by Stupiansky and colleagues (ages 17–19, mean = 18.3). Moreover, our test of mediation at the between-person level specified the intercept, or adherence at age 13.77, as the outcome. Therefore, it is possible that self-efficacy is a mechanism via which impulse control is related to individual differences in adherence in late, but not mid, adolescence.

Although aspects of self-regulation—including impulse control—are often targets of behavioral interventions for adolescents, they are challenging factors to change because the neural processes that underlie regulatory abilities are still being refined (Casey, 2019; Steinberg, 2018). Given this developmental context, it may be appealing to attempt to improve diabetes management by helping adolescents gain confidence rather than helping adolescents control impulses in socially- or emotionally-laden situations. Our findings suggest that maturational gains in impulse control and increases in self-efficacy are both positively associated with adherence in youth with T1D. Specifically, time-specific improvements in self-efficacy did not entirely account for the behavioral benefits associated with improvements in impulse control. Throughout adolescence, there may be occasions, or periods of time, during which youth successfully and consistently self-manage T1D because they have made strides in their ability to control impulses. Likewise, there may be periods of time during which an adolescent’s ability to regulate impulses is stagnant but the adolescent has gained enough diabetes-related confidence to motivate increases in self-care behaviors. Thus, long-term intervention efforts to increase both self-efficacy and impulse control may yield notable benefits within individuals over time. Overall, this study shows that cumulative increases in impulse control and self-efficacy coincide with a temporary boost in adherence, in spite of the underlying age-related decline in T1D management that is observed across this developmental period (ages 8–16). These temporary successes in youth-reported adherence may be meaningful experiences for an adolescent’s adjustment in both T1D-related and other domains.

While the present study has strengths, including its longitudinal design, we interpret our findings with caution, as they were limited to youths’ report of adherence. Because the associations only held for youth-reported adherence, shared method variance cannot be ruled out as an explanation for the study findings. Despite the importance of this limitation, our reliance on youth-reported predictors is nonetheless supported by a prior study showing that youth self-reports of impulsivity were better predictors of various child- and parent-reported youth outcomes (e.g., risk-taking, aggression, attentional problems) than were parent reports (Zapolski & Smith, 2013). In that study, Zapolski & Smith (2013) showed that even when there is convergent validity between reporters, relying on youth self-reports of constructs like impulse control may be more valuable than parent reports for some youth behaviors. Future replications of this study should nonetheless include parents’ perceptions of their child’s regulatory abilities as predictors of youths’ self-care behaviors (e.g., Miller et al., 2013).

Another limitation of the present study is that our measure of regulatory abilities was limited to impulse control, which is one of several skills that encompass self-regulation (Nigg, 2017). Future research in this area should incorporate multiple indicators of self-regulation, including emotional regulation (Hughes, Berg, & Wiebe, 2012). It may also be important for future studies to include indicators of self-regulation that are specific to diabetes, such as the Diabetes-Related Executive Functioning scale (Duke, Raymond, & Harris, 2014). The current findings are also limited by the relatively small sample which did not allow a more nuanced investigation. For example, the fixed-effects models specified in the current study assumed that associations would be similar for all individuals, even though in the real world the strength of the associations between impulse control, self-efficacy, and adherence is likely to vary across individuals. For example, impulse control may not develop at the same rate for all individuals and this variability is likely to relate to the relative changes in self-efficacy and T1D management that adolescents may experience. Replicating the current findings in a larger sample and exploring whether the mediated effects reported here vary across individuals would be a valuable contribution to this line of research. Lastly, we cannot make causal inferences from the concurrent associations observed in the current study, and it will be important for future research to consider the bidirectionality of the relationships explored reported here. For example, since self-efficacy entails a sense of mastery that often results from experience, it is possible that youth feel more self-efficacious following successful management of their illness.

The current study findings underscore the importance of both impulse control and self-efficacy for T1D management in adolescence. Efforts to improve adherence in youth with T1D will benefit from consideration of youth impulse control and self-efficacy, as both of these factors are positively associated with changes in T1D management from late childhood to late adolescence. Environments that consistently foster improvements in impulse control and enrich adolescents with confidence in their own abilities may gradually contribute to improvements in self-care behaviors within-individuals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the children and parents who participated in this study. They also thank the Diabetes Center for Children and the Cystic Fibrosis Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia for supporting this program of research.

Funding

This work was supported by T71MC30798 from the Maternal & Child Health Bureau (MCHB) and grant #1R01HD064638-01A1 awarded to the senior author from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the MCHB, NICHD, or the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

References

- Babler E., Strickland C. J. (2015). Moving the journey towards independence: adolescents transitioning to successful diabetes self-management. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 30, 648–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagner D. M., Williams L. B., Geffken G. R., Silverstein J. H., Storch E. A. (2007). Type 1 diabetes in youth: the relationship between adherence and executive functioning. Children’s Health Care, 36, 169–179. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (2004). Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education and Behavior, 31, 143–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg C. A., King P. S., Butler J. M., Pham P., Palmer D., Wiebe D. J. (2011). Parental involvement and adolescents’ diabetes management: the mediating role of self-efficacy and externalizing and internalizing behaviors. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 36, 329–339. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsq088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg C. A., Wiebe D. J., Suchy Y., Hughes A. E., Anderson J. H., Godbey E. I., White P. C. (2014). Individual differences and day-t-day fluctuations in perceived self-regulation associated with daily adherence in late adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39, 1038–1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey B. J. (2015). Beyond simple models of self-control to circuit-based accounts of adolescent behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 295–319. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey B. J. (2019). Healthy development as a human right: lessons from developmental science. Neuron, 102, 724–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A., Augenstein T. M., Wang M., Thomas S. A., Drabick D. A. G., Burgers D. E., Rabinowitz J. (2015). The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 141, 858–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke D. C., Harris M. A. (2014). Executive function, adherence, and glycemic control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: a literature review. Current Diabetes Reports, 14, 532–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke D. C., Raymond J. K., Harris M. (2014). The diabetes related executive functioning scale (DREFS): pilot results. Children’s Health Care, 43, 327–344. doi:10.1080/02739615.2013.870040 [Google Scholar]

- Hanna K. M., Guthrie D. (2000). Parents’ and adolescents’ perceptions of helpful and nonhelpful support for adolescents’ assumption of diabetes management responsibility. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 24, 209–223. doi: 10.1080/014608601753260317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden K. P.& Tucker-Drob E. M. (2011). Individual differences in the development of sensation seeking and impulsivity during adolescence: Further evidence for a dual systems model. Developmental Psychology, 47, 739–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayaki J., Herman D. S., Hagerty C. E., de Dios M. A., Anderson B. J., Stein M. D. (2011). Expectancies and self-efficacy mediate the effects of impulsivity on marijuana use outcomes: an application of the acquired preparedness model. Addictive Behaviors, 36, 389–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman L., Stawski R. S. (2009). Persons as contexts: evaluating between-person and within-person effect in longitudinal analysis. Research in Human Development, 6, 97–120. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes A. E., Berg C. A.& Wiebe D. J. (2012). Emotional processing and self-control in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 37, 925–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannotti R. J., Schneider S., Nansel T. R., Haynie D. L., Plotnick L. P., Clark L. M., Simons-Morton B. (2006). Self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and diabetes self-management in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 27, 98–105. doi:10.1097/00004703-200604000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston-Brooks C. H., Lewis M. A., Garg S. (2002). Self-efficacy impacts self-care and HbA1c in young adults with type I diabetes. Psychosomatic Medicine, 64, 43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King P. S., Berg C. A., Butner J., Butler J. M., Wiebe D. J. (2014). Longitudinal trajectories of parental involvement in type 1 diabetes and adolescents’ adherence. Health Psychology, 33, 424–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krull J. L., MacKinnon D. P. (2001). Multilevel modeling of individual and group level mediated effects. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 36, 249–277. doi:10.1207/S15327906MBR3602_06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca A. M., Follansbee D., Skyler J. S. (1990). Developmental and behavioral aspects of diabetes management in youngsters. Children’s Health Care, 19, 132–139. [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield C. H., Craven J. L., Rodin G. M., Daneman D., Murray M. A., Rydall A. C. (1992). Relationship of self-efficacy and binging to adherence to diabetes regimen among adolescents. Diabetes Care, 15, 90–94. doi:10.2337/diacare.15.1.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. M., Rohan J. M., Delamater A., Shroff-Pendley J., Dolan L. M., Reeves G., Drotar D. (2013). Changes in executive functioning and self-management in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: a growth curve analysis. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 38, 18–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller V. A., Jawad A. F. (2019). Decision-making involvement and prediction of adherence in youth with type 1 diabetes: a cohort sequential study. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 44, 61–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki Y., Raudenbush S. W. (2000). Tests for linkage of multiple cohorts in an accelerated longitudinal design. Psychological Methods, 5, 44–63. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.5.1.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L.K., Muthén B.O. (1998. –2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Nigg J. T. (2017). Annual research review: on the relations among self-regulation, self-control, executive functioning, effortful control, cognitive control, impulsivity, risk-taking, and inhibition for developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58, 361–383. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott J., Greening L., Palardy N., Holderby A., DeBell W. K. (2000). Self-efficacy as a mediator variable for adolescents’ adherence to treatment for insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Children’s Health Care, 29, 47–63. doi:10.1207/s15326888chc2901_4 [Google Scholar]

- Pan H., Liu S., Miao D., Yuan Y. (2018). Sample size determination for mediation analysis of longitudinal data. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18, 32–43. doi:10.1186/s12874-018-0473-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton K. A., Gullo M. J., Connor J. P., Chan G. C., Kelly A. B., Catalano R. F., Toumbourou J. W. (2018). Social cognitive mediators of the relationship between impulsivity traits and adolescent alcohol use: identifying unique targets for prevention. Addictive Behaviors, 84, 79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K. J., Zyphur M. J., Zhang Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15, 209–233. doi:10.1037/a0020141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman E. P., Harden K. P., Chein J. M.& Steinberg L. (2015). Sex differences in the developmental trajectories of impulse control and sensation-seeking from early adolescence to early adulthood. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman E. P., Smith A. R., Silva K., Icenogle G., Duell N., Chein J., Steinberg L. (2016). The dual systems model: review, reappraisal, and reaffirmation. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 17, 103–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva K., Miller V. A. (2019). The role of cognitive and psychosocial maturity in type 1 diabetes management. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64, 622–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stupiansky N. W., Hanna K. M., Slaven J. E., Weaver M., Fortenberry D. (2013). Impulse control, diabetes-specific self-efficacy, and diabetes management among emerging adults with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 38, 247–254. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jss110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaid E., Lansing A. H.& Stanger C. (2018). Problems with self-regulation, family conflict, and glycemic control in adolescents experiencing challenges with managing type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 43, 525–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. (2018). Regulating our enthusiasm for self-regulation interventions. JAMA Pediatrics, 172, 520–522. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger D. A. (1997). Distress and self-restraint as measures of adjustment across the life span: confirmatory factor analyses in clinical and nonclinical samples. Psychological Assessment, 9, 132–135. [Google Scholar]

- Wiebe D. J., Chow C. M., Palmer D. L., Butner J., Butler J. M., Osborn P., Berg C. A. (2014). Developmental processes associated with longitudinal declines in parental responsibility and adherence to Type 1 diabetes management across adolescence. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39, 532–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebe D. J., Berg C. A., Mello D., Kelly C. S. (2018). Self- and social regulation in type 1 diabetes management during late adolescence and emerging adulthood. Current Diabetes Reports, 18, 23–32. doi: 10.1007/s11892-018-0995-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood J. R., Miller K. M., Maahs D. M., Beck R. W., DiMeglio L. A., Libman I. M., Woerner S. E; T1D Exchange Clinic Network. (2013). Most youth with type 1 diabetes in the T1D Exchange Clinic Registry do not meet American Diabetes Association or International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes clinical guidelines. Diabetes Care, 36, 2035–2037. doi: 10.2337/dc12-1959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski T. C., Smith G. T. (2013). Comparison of parent versus child-report of child impulsivity traits and prediction of outcome variables. Journal of Psychopathology Behavioral Assessment, 35, 301–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Zyphur M. J., Preacher K. J. (2009). Testing multilevel mediation using hierarchical linear models: problems and solutions. Organizational Research Methods, 12, 695–719. doi: 10.1177/1094428108327450 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.