Abstract

Background:

With improved survivorship rates for colorectal cancer (CRC), more CRC survivors are living with long-term disease and treatment side effects. Little research exists on CRC symptoms or symptom management guidelines to support these individuals after cancer treatments.

Objectives:

To systematically review symptom experiences, risk factors and the impact of symptoms; and to examine pooled frequency and severity of symptoms via meta-analyses in CRC survivors after cancer treatments.

Methods:

Relevant studies were systematically searched in 7 databases from 2009 to 2019. Meta-analysis was conducted for pooled estimates of symptom frequency and severity.

Results:

Thirty-five studies met the inclusion criteria. Six studies assessed multiple CRC symptoms, while 29 focused on a single symptom, including peripheral neuropathy, psychological distress, fatigue, body image distress, cognitive impairment, and insomnia. The pooled mean frequency was highest for body image distress (78.5%). On a 0-100 scale, the pooled mean severity was highest for fatigue (50.1). Gastrointestinal and psychological symptoms, peripheral neuropathy, and insomnia were also major problems in CRC survivors. Multiple factors contributed to adverse symptoms such as younger age, female gender, and lack of family/social support. Symptoms negatively impacted quality of life (QOL), social and sexual functioning, financial status, and caregivers’ physical and mental conditions.

Conclusions:

CRC survivors experienced multiple adverse symptoms related to distinct risk factors. These symptoms negatively impacted patients and caregivers’ wellbeing.

Implications for Practice:

Healthcare providers can use study findings to better assess and monitor patient symptoms after cancer treatments. More research is needed on CRC-specific symptoms and their effective management.

Keywords: systematic review, meta-analysis, colon cancer, rectal cancer, symptoms, after treatments, survivorship, risk factors, impact, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer among both men and women in the U.S.1 In 2017, 135,430 individuals were newly diagnosed with CRC and 50,260 were projected to die from the disease.1 Despite this, increasing numbers of patients are surviving CRC. In the U.S. the survival rate is 90% at 5 years for patients with localized cancer and 63% at 5 years for patients across all stages of CRC combined. While early diagnosis and advanced treatment have increased CRC survival rates, many individuals live with long-term side effects that span the cancer treatment trajectory.2 CRC survivors have special health care challenges and needs.3 Once side effects from primary cancer treatments subside, many CRC survivors continue to report a high burden of symptoms such as fatigue, bowel dysfunction, depression, and insomnia.3 This symptom burden is the major factor associated with quality of life (QOL) after treatment ends and with overall CRC survivorship.3

Non-specific symptoms in CRC survivors include changed bowel habits, general abdominal discomfort, weight loss, and fatigue.4 By contrast, symptoms in advanced CRC cases - including blood and mucus in stool, nausea, vomiting, and some emergency conditions, such as bowel obstruction or perforation - have been directly linked to the cancer itself or treatment side effects or both.4 The multimodality of CRC treatments (e.g., extensive abdomino-pelvic surgery, pelvic radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and surgical resection) can further alter bowel function, sphincter loss, and permanent ostomies. This often leads to sexual dysfunction, psychological distress, physical and social limitations, and insomnia.5 These multiple symptoms often persist after treatment ends and continue into survivorship.5 To ensure maximum long-term wellbeing, proper monitoring and management of these physical and psychological symptoms are needed for CRC survivors.6

Adverse symptoms after cancer treatments may also impact CRC survivors’ ability to adhere to the American Cancer Society (ACS) recommendations for physical activity and nutrition, key lifestyle factors linked to survival outcomes.7 In a recent prospective cohort study of stage III colon cancer patients who finished treatments (N = 999), those who followed the ACS guidelines had a 42% lower risk of death. However, many CRC survivors face ongoing health challenges, such as gastrointestinal (GI) distress, psychological problems, and fatigue.7 These adverse symptoms in turn have been negatively associated with adherence to a lifestyle consistent with the ACS guidelines on physical activity and nutrition.7

Given that the number of CRC survivors is dramatically increasing, more attention is needed to understand post-treatment symptom experiences in order to develop tailored interventions to increase holistic wellbeing among long-term CRC survivors. To date, a few studies have focused on symptomology in this patient group after cancer treatments, compared to research on survivors of other major diseases such as breast, lung, and prostate cancer.3,6 We found only one integrative review that examined a small set of studies (N = 5) focused on symptoms in CRC survivors receiving chemotherapies.3 Only 2 of these studies evaluated associations between demographic and treatment characteristics, symptom burden, and QOL outcomes. Tantoy and colleagues3 state that symptoms in post-treatment CRC survivors are poorly understood, specifically as they relate to risk factors and impacts on life. This lack of information also makes it difficult to develop effective symptom management guidelines.3

To address this research gap and improve the QOL among CRC survivors, we performed a systematic review of literature on symptom experiences in CRC survivors after cancer treatments. Our primary aim was to systematically review (1) the symptoms that adult CRC survivors experience, (2) the risk factors for these symptoms, and (3) the impacts of these symptoms. Our secondary aim was to conduct meta-analyses to evaluate the frequency and the severity of symptoms in adult CRC survivors following cancer treatments.

Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework (Figure 1) for this study is based on the Symptom Management Model.8 As seen in Figure 1, this model addresses the inter-correlations among three major concepts (i.e., symptom experiences, symptom management strategies, and symptom outcomes). The three domains - person, environment and health & illness – are contextual variables influencing symptom management.8 For symptom experience concept, an individual’s experience consists of perception, evaluation, and response to a symptom, processes which are bi-directionally related. Effective symptom management is based on each person’s unique assessment of their symptom experience. Symptom outcomes — including functional status, self-care, emotional status, costs, mortality, QOL, and morbidity — result from both symptom experience and management.8 In our review, we analyzed and synthesized study data by mapping symptom experiences of CRC survivors to elements of the Symptom Management Model (Figure 1). We focused on “symptom experiences”, “symptom outcomes”, and “risk factors of symptoms (under the concept of symptom management strategies)” in the Symptom Management Model.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework: Symptom Management Model for CRC Survivors.

Note. Symptom experiences, disease outcomes, and symptom management strategies are interrelated within the contexts of health and illness, person, and environment. CRC symptoms, potential impacts of CRC symptoms, and potential risk factors of CRC symptoms are focused on understanding the dynamics and interplay of these various health components to inform effective interventions for CRC survivors. Adapted from Dodd M. et al. Advancing the science of symptom management. J Adv Nurs, 2001:33(5):668-676.

Abbreviations: CRC, colorectal cancer; QOL, quality of life.

METHODS

Search Strategies and Data Sources

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline for systematic review and meta-analysis,9 we conducted a systematic literature review to integrate findings from quantitative studies. Our systematic literature research examined 7 electronic databases: Scopus, CINAHL, Medline via PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, Cochrane Library (Review and CENTRAL), and PsycINFO. We focused on symptom experiences among CRC survivors after cancer treatments. Using MeSH terms and manual searches, the key words examined were: “colorectal cancer,” “colon cancer,” “rectal cancer,” “cancer survivor*,” “after treatment*,” “chemotherapy,” “radiotherapy,” “surgery,” “symptom*,” “bowel,” “GI,” “psychological distress,” “fatigue,” “pain,” “peripheral,” “sleep,” “stress,” “cognitive,” “neuropathy,” “urinary,” and “sexual,” in combination with “risk factors,” “outcomes,” and “impact.” Other eligible studies were identified by reviewing the cited references from the obtained published studies.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (a) published over the last 15 years from June2004 to May 2019; (b) reported symptoms after any cancer treatments in CRC survivors using quantitative measures; (c) based on original or experimental data; (d) examined patients aged over 18 years or older with CRC; and (e) published in English. Studies were excluded studies if they: (a) presented only qualitative results; (b) were not published in English; (c) were review papers or editorials, meta-syntheses, theory-based works, dissertations, and case studies; (d) collected symptom data only before and/or during cancer treatments; (e) reported only incidence of symptom diagnosis (e.g., generalized anxiety disorders, major depressive disorders); or (f) were focused on caregivers.

Since sexual dysfunction and urinary symptoms in CRC survivors have already been systematically reviewed,10,11 we excluded studies that primarily assessed these symptoms from our analyses. There were no restrictions regarding when symptoms were assessed after cancer treatments. This could have occurred after treatments, including the recovery phase, or during the long-term survivorship phase. This approach ensured all relevant literature was included.

Study Selections and Screening

Two authors (CH and GY) independently assessed the collected articles for study eligibility. All titles, abstracts, and full-text articles were reviewed independently by each author based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. In the case of disagreement between the two authors, a third author (KS) was available for arbitration.

Methodological Quality Appraisal

Two authors (CH and GY) independently evaluated the methodological quality of each article using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklists (2017) for quantitative observational studies. The CASP checklists, consisting of 12 questions, appraise research rigor and risk of investigator bias.12 Each question is answered with “Yes,” “Can’t tell,” or “No.” There is, however, no established standard of the CASP checklists to designate an article as high or low quality.12 Using an arbitrary threshold, commonly used for critical appraisal of a research study,12 we evaluated an article as “high” quality if it met at least 80% of the checklist criteria (e.g., 10 of 12 questions in each study), “low” quality if it met 50% or less of the criteria, and “medium” quality if it met > 50% and < 80% of the criteria. In cases of continued disagreement between the two authors, a third author (KS) arbitrated.

Data Extraction and Data Synthesis

In this review, the following variables were extracted: study aims; publication year; study design; country of research; setting of research; sample size; participant characteristics; methods of measuring symptoms; symptom experiences; risk factors for adverse symptoms; outcomes of symptoms; and other symptom-related factors, results, and conclusions. Data were extracted into self-developed standardized forms by the first author (CH) and verified for accuracy and completeness by the other authors (GY and KS). Discrepancies were resolved through consensus-building discussions among the three authors. We synthesized the extracted data and presented the findings as narrative descriptions and descriptive statistics.

Meta-Analytical and Statistical Methods

To get more precise estimates of symptom frequency and severity reported among CRC survivors, a meta-analysis was used to combine the symptom data from multiple studies in order to increase power over findings from individual studies 13,14 The pooled frequency and severity of symptoms were computed with weighted mean and standard errors, along with 95% confidence interval (CI).13,14 We included only studies that reported the frequency (% of research participants with a symptom) and/or the mean severity of a symptom using numerical rating scales. In addition, the pooled frequency and severity estimates were analyzed only if symptom frequency or severity was present in at least two studies per symptom. For severity data, mean severity was converted to a 0 to 100 scale from different scales, where a higher score indicates worse symptomology.13,14 Because there are no validated cut-off points to interpret a pooled mean severity as mild, moderate, or severe, we compared individual symptoms based on their relative value of pooled mean severity.

Forest plots were presented with pooled mean estimates of frequency or severity of symptoms with 95% CIs. Heterogeneity was analyzed with Q statistics as a measure of squared variance in which p <.10 was considered statistically significant, and with I2 statistics (I2 < 25.0% = no heterogeneity; I2 > 75.0% = high or extreme heterogeneity). For data with high heterogeneity, random effects model results were presented. Otherwise, we chose fixed-effects model results. A two-sided p <.05 was considered statistically significant.

For descriptive statistical analysis, the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 23.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) was used. For meta-analysis, the statistical analyses, including forest plots, were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (version 2.2.050; Biostat, Engelwood, NJ).

RESULTS

Included Studies and Methodological Quality Evaluation

The search strategies yielded 473 published articles after excluding duplicates. A review of titles and abstracts reduced the number of relevant studies to 57 and a total of 35 were identified for final analysis, following assessment of the full-text articles. Three of these studies were excluded from the meta-analyses due to absence of symptom severity and frequency data15 or symptoms were reported on only one study.16,17 A flow chart of our literature search is depicted in Figure 2, and details for the 35 studies are described in Tables 1 and 2. Results from evaluating each of the 35 quantitative studies using CASP tools are reported in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. The inter-rater agreement between the two authors was 98.3%. No studies were excluded due to low quality.

Figure 2.

Article Search Flow Diagram for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses

Table 1.

Studies focusing on Multiple Symptoms in Colorectal Cancer Survivors (N = 6)

| Author(s)/ Yearref# |

Aim | Study Design/ Country |

Setting/Sample (mean age, sex, ethnicity) |

Primary Symptom Measures |

Cancer Related Factorsa |

Findings Regarding Symptom Experiences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lin et al. (2018)24 | To assess pelvic floor symptoms, physical and psychological symptoms, and QOL before and after surgery for CRC. | Prospective longitudinal design. Australia |

30 survivors with CRC from 2 urban hospitals (colon 67%, rectal 33%; 56 y.o.; 47% females; 100% Caucasian) | -Symptom: Australian Pelvic Floor Questionnaire, Physical Activity Questionnaire, HADS, EORTC- QLQ-C30,CR29 |

- Stage I (20%), II (36.7%), III (33.3%) - Surgery+CTx+ RTx (13.3%), Surgery + CTx (50%), Surgery (100%) |

Time to assess symptoms: Baseline and at 6 months after surgery. Symptoms reported: Pelvic floor symptoms, anxiety, fatigue, insomnia, appetite loss, financial difficulties, body image, weight loss, and urinary frequency were reported as very severe symptoms. Bowel symptoms were significantly worse at post-surgery. Impacts of symptoms: low physical activity. |

| Drury et al. (2017)2 | To examine pain and QOL. | Cross-sectional design. Ireland |

252 survivors with CRC from cancer centers (colon 64%, rectal 24%; 66 y.o.; 45% females; 100% Caucasian) | -Pain, depression and anxiety: FACT-C, and EuroQOL-5D | - Previous: Surgery (91%) CTx (60%), RTx (25%) - Current: CTx (7%), RTx (5%) |

Time to assess symptoms: Mean 5 years after treatment. 40% of survivors reported severe pain, and prevalent in CRC survivors for long-time Pain-related other symptoms: Fatigue, bowel dysfunctions, sleep disturbances. Risk factors of pain: Younger age, female, current CTx, and previous RTx. Impacts of pain on QOL: Poor self-reported health (cancer survivorship quality), daily life interferences, poor physical, emotional, functional, social/family and CRC-specific well-being. |

| Gosselin et al. (2016)22 | To determine symptom frequency and intensity, and identify cluster based on the symptom-subgroups. | Prospective, longitudinal, population-based design. USA |

275 survivors with RC from a Cancer Surveillance database (63 y.o.; 34% females; 68% Caucasian) | -Symptoms: Fatigue (Short-Form Health Survey), Pain (Brief Pain Inventory), Symptoms (EORTC QLQ-C30, and CR 29) | -Stage I (14%), II (33%)), III (44%), IV (7%), Recurrence (9%) -Surgery (50%), Colostomy current (40%) & past (19%), CTx (100%), RTx (100%) |

Time to assess symptoms: Baseline and 15 months after diagnosis. Symptom reported: Fatigue (most common symptoms), GI symptoms, insomnia (next common symptoms). Risk factors of symptoms: CTx-Oxaliplatin (pain in hands and feet), Colostomy-related concerns, younger age and non-married or partnered. Symptom subgroups: Cluster 1 (minimally symptomatic, n = 40), Cluster 2 (Tired/trouble sleeping, n = 138), Cluster 3 (moderate symptomatic, n = 42), Cluster 4 (highly symptomatic, n = 55). |

| Bailey et al. (2015)5 | To investigate symptoms of long-term survivors, and examine differences by age at diagnosis. | Cross-sectional design. USA |

830 survivors with CRC from tertiary Cancer Center CRC registry (colon 46%, rectal 52%, both 2%; 56 y.o.; 44% females; 84% Caucasian) | -Symptoms: EORTC-CR 29. | -Mean 11 years after diagnosis -Stage I (50%), II (31%), III (9.6%) -Surgery (96%), CTx (81%), RTx (54%). Permanent Colostomy (15%) |

Time to assess symptoms: At least 5 years after cancer diagnosis. Symptom reported: Anxiety, GI symptoms, sexual dysfunction, and urinary symptoms (most common). Risk factors of symptoms: “Age-at-diagnosis” Younger-onset survivors reported worse anxiety, body image, and embarrassment with bowel movements, whereas later-onset survivors highlighted sexual dysfunction, micturition problems, and impotence. Impacts of symptoms: Troubles with sexual relationships, body image change, long-term coping. |

| van Ryn et al. (2014)47 | To assess symptoms and risk factors of symptoms. | Cross-sectional design. USA |

1,109 survivors with CRC from the Veterans Affairs Cancer Registry (65 y.o.; gender not specified; 81% Caucasian) | -Symptoms frequency: Patient-Centered Quality of Supportive Care (PICO) tool | -Stage I (35%), II (25%), III (20%), IV (17%) -Surgery (81%), CTx (40%), RTx |

Time to assess symptoms: At least 8 years after diagnosis. Five symptoms categories assessed: Fatigue, bowel problems, pain, fatigue, depression. Risk factors of symptoms and symptom care quality: Non-Hispanic White, and older age were less likely to report symptoms. CTx, and Stage IV were positively associated with symptoms. The better coordination of care was associated with better symptom management. |

| Cotrim & Pereira (2008)33 | To identify and assess the impact on symptoms and QOL in survivors undergoing surgery. | Cross-sectional design. Portugal |

153 survivors with CRC from Cancer Center (67% colon, 33% rectal; 64 y.o.; 33% females; 100% Portuguese) | -Symptoms: EORTC QLQ-C30 and CR 38, Body Image Scale, | -Surgery (48%), Surgery+CTx (22%), Surgery+CTx+RTx (67%), Ostomy (30%) |

Time to assess symptoms: 6-8 months after surgery. Symptoms reported: Sexual dysfunction, fatigue, and diarrhea. Risk factors of symptoms: Undergoing stoma predicted higher psychological distress, fatigue, diarrhea, sexual problems, and poor QOL than non-stoma survivors. Impacts of symptoms: Poor QOL, and caregivers’ overall symptom burden and their QOL. Body image disturbances, and sexual problems. |

Note. Abbreviation: CRC, colorectal cancer; CTx, chemotherapy; EORTC-QLQ, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QOL Questionnaire; FACT-C, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal; GI, gastrointestinal; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; QOL, quality of life; RC, rectal cancer; RTx, radiation therapy; YO, years old.

Only data provided in the selected studies are presented in the table.

Table 2.

Studies focusing on Single Symptom in Colorectal Cancer Survivors (N = 29)

| Author(s)/ Yearref# |

Aim | Study Design/ Country |

Setting/Sample (mean age, sex, ethnicity) |

Primary Symptom Measures |

Cancer Related Factorsa |

Findings Regarding Symptom Experiences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Peripheral Neuropathy (n = 9) | ||||||

| Lu et al., (2019)45 | To examine the relationships among restriction of daily activity, mood, and QOL in CRC after CTx. | Cross-sectional design. Taiwan |

103 survivors with CRC in inpatient settings (100% both colon and rectal; 61-70 y.o; 44.7% females; Asian) | -Neuropathic pain symptoms inventory (NPSI) | -Stage II (5.8%), III (60.2%). -CTx ‘Oxaliplatin’(100%) |

Time to assess symptoms: After CTx, but specific time point was not addressed. Severity of neuropathic pain: 13.66 out of total 100 points (mild). Risk factors of neuropathic pain: Restrictive daily activity, negative mood status. Impacts of neuropathic pain: QOL |

| Soveri et al.,(2019)39 | To examine the long-term neuropathy after CTx. | Cross-sectional design. Finland |

144 survivors with CRC in outpatient clinics (62% colon, 38% rectual; 61 y.o.; 58% females; Finlandian) | - Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy (EORTC CIPN20) questionnaires. | -Stage II (77%), III (11%). -CTx ‘Oxaliplatin’ (100%), RTx (34%) |

Time to assess symptoms: At median 4.2 years after CTx. Neuropathy: 69% of survivors reported long-term sensory neuropathy including pain and peripheral tingling severity. Risk factors of neuropathy: CTx (Oxaliplatin) Impacts of neuropathy: QOL, specifically physical functioning and role functioning QOL. |

| Vatandoust et al., (2014)42 | To explore the frequency of persistent peripheral neuropathy after CTx. | Cross-sectional design. Australia |

27 survivors with CRC in two cancer centers (78% colon, 18.5% rectal; 3.7% both colon and rectal; 66 y.o.;33.3% females; Australian) | -Neuropathy: Survivors answered a 12-item questionnaire (NTX-12). | -Stage III (70.4%), IV (29.6%) -CTx ‘Oxaliplatin’ (100%) |

Time to assess symptoms: At median 3 years after CTx. Severity: Grade 2 and 3 assessed by NTX-12 were prevalent. Risk factors of neuropathy: Dose of Oxaliplatin, a history of regular alcohol use. |

| Velasco et al., (2014)29 | To define early predictors of neuropathy after CTx. | Prospective design. Spain |

200 survivors with CRC at four cancer centers (100% both colon and rectal; 63.6 y.o.; 40% females; Europeans) | -Neuropathy: Total Neuropathy Scale (TNS) | -CTx ‘Oxaliplatin’ (100%) |

Time to assess symptoms: At 1 month after CTx. Symptoms of neuropathy: Severity: 4.1 (mild, 0-28 score). Neuropathy: Severity and frequency decreased over time from baseline, but persistent over time. Risk factors of neuropathy: CTx, previous dose of Oxaliplatin. |

| Mols et al., (2013)32 | To examine the neuropathy after CTx | Cross-sectional design. Netherlands |

500 survivors with CRC registered in Dutch cancer registry (67% colon, 33% rectal; 66.7 y.o; 42% females; European) | -Neuropathy: EORTC QLQ Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy 20. | -Years since diagnosis (5.5 y.o.) -Stage I (5%), II (14%), III (70%), IV (8%) -Surgery (46%), CTx (5%), Surgery+RTx (24%), Surgery+CTx (22%),Surgery+CTx+ RTx (9%) |

Time to assess symptoms: 2 to 11 years after diagnosis. Neuropathy: 20% of survivors reported neuropathy including sensory, motor and autonomic neuropathy; 10.1 (mean severity of neuropathy including sensory, motor and autonomic neuropathy) in 0-100 scale. Risk factors of neuropathy: CTx, Oxaliplatin-based CTx was significantly associated with severity of neuropathy. Impacts of neuropathy: QOL. |

| Tofthagen et al., (2013)41 | To examine the neuropathy after CTx. | Cross-sectional design. USA. |

111 survivors with CRC from the cancer center (100 % both colon and rectal; 61 y.o.; females 53%; 98% Caucasian) | -Neuropathy: Chemotherapy Induced Peripheral Neuropathy Assessment Tool - |

-Stage III (67%), IV (32%) -CTx regimen (100%): Oxaliplatin |

Time to assess symptoms: On average after 3 years of CTx: Neuropathy: Frequency: 89%, Severity: 68.7 (0 to 248 scale, higher indicates severe). Risk factors of neuropathy: Poor sleep, depression, Oxaliplatin-based CTx. Impact of neuropathy: Poor QOL. |

| Argyriou et al., (2012)19 | To examine the peripheral neuropathy after CTx. | Prospective design. Greece |

150 survivors with CRC in outpatient settings (100% both colon and rectal; 63.3 y.o; 40% females; European) | -Neuropathy: Total Neuropathy Scale (TNS) | -Not specified. -CTx regimen (100%): Oxaliplatin (FOLFOX-4 or XELOX) |

Time to assess symptoms: At within 1 month after CTx: Neuropathy: Frequency: 71.5%, Severity: 6.5 (mild in 0-28 point severity scale). Severity and frequency decreased over time from baseline, but persistent over time. Risk factors of neuropathy: Using FOLFOX is associated with higher severity of neuropathy, compared to the group with XELOX. |

| Kidwell et al., (2012)36 | To examine the long-term neuropathy after CTx | Cross-sectional design. USA |

92 survivors with CRC registered in Long-Term Survivors study (71.7% colon, 28.3% rectal: 50-59 y.o as majority; 34.8% females; Not specified) | -Neuropathy: Survivors answered a 12-item questionnaire (NTX-12) | -Not specified -CTx ‘Oxaliplatin’ (100%) |

Time to assess symptoms: At the time of follow-up (29 ± 4 months post-oxaliplatin): Neuropathy: Frequency: 79.2%, Severity: 4.66 (0-48 score). Risk factors of neuropathy: CTx. |

| Park et al., (2011)38 | To describe the neuropathy. | Cross-sectional design. Australia |

22 survivors with CRC from the medical registry of oncology hospital (60 y.o.; 37.5% females, Australian) | -Neuropathy: Total Neuropathy Scale (TNS) | -Stage III (58%), IV (42%) -CTx (100%) |

Time to assess symptoms: At a median of 25 months post-oxaliplatin: Neuropathy: Frequency: 79.2%, Severity: 4.1 (mild, 0-28 score). Risk factors of neuropathy: Previous dose of CTx, duration of CTx more than 3 months. |

| B. Psychological Distress (i.e., Depression and Anxiety) (n = 7) | ||||||

| Mols et al. (2018)18 | To assess frequency, risk factors and impacts of anxiety and depression. | Prospective longitudinal design (across a 4-year time period). Netherlands |

2625 survivors with CRC from Cancer registry (colon 61%, rectal 39%; 69 y.o.; 45% females; 100% Caucasian European) | -Psychological distress: HADS | -Stage I (30%), II (36%), III (38%), IV (4%) -Surgery (100%), CTx (29%), RTx (31%) |

Time to assess symptoms: Mean 5 years after diagnosis. Psychological distress: Severity and frequency (approx. 20%) of depression and anxiety were significantly higher in CRC survivors compared to the general population (approx. 10%). Mean severity of anxiety (4.6), depression (4.4). Risk factors of psychological distress: single or non-married, low education level, comorbid condition, younger age, and female. Impacts of psychological distress: Lower global QOL, lower physical, role cognitive, emotional, and social functioning QOL. Even years after diagnosis and treatment, anxiety and depression and their negative effect on HRQOL are still high in CRC survivors. |

| Trudel-Fitzgerald et al. (2018)27 | To examine psychological distress and its’ impact on life style. | Prospective longitudinal design USA |

372 women with CRC from Nurses’ Health Study cohort (50% colon, 50% rectal; 66 y.o.; 100% females) | -Depression: Mental Health Index-5 -Anxiety: Self-report Crown Crisp Index |

-Cancer stage (75% women with 0-II). |

Time to assess symptoms: At baseline and mean 4 years after diagnosis. Psychological distress: Frequency: Depression (12%), and anxiety (26%). Impacts of psychological distress: Unhealthier lifestyle scores throughout follow-up. Treating psychological symptoms early in the cancer trajectory may not solely reduce psychological distress but also promote healthier lifestyle. |

| Akyol et al. (2015)44 | To examine psychological distress and impacts of psychological distress. | Cross-sectional design. Turkey |

105 survivors with CRC from university cancer center (colon 67%, rectal 33%; 53 y.o.; 31% females; 100% Turkish) | -Psychological distress: HADS |

-Stage I (51%) II (24%), III or IV (25%) -Having current stoma (29%) |

Time to assess symptoms: After surgery (specific time point was not addressed). Psychological distress: Frequency (Depression, 44%; anxiety, 29%), Severity (Depression 6.5; anxiety 8.0) Risk factors of psychological distress: Gender (being female), advanced cancer stage Impacts of psychological distress: Low global QOL, physical functioning, sexual function, sexual problems with partners, financial problems. |

| Zhang et al. (2015)43 | To explore the influence of self-efficacy and demographic, disease-related, and psychological factors on symptoms. | Cross-sectional design. China |

252 survivors with CRC from outpatient clinics (colon 50%, rectal 50%; 53 y.o.; 34% females; 100% Chinese) | -Psychological distress: HADS | -Stage II (42%), III (58%). -Surgery (100%), CTx (100%) |

Time to assess symptoms: After post-surgical adjuvant CTx (specific time point was not addressed). Psychological distress: Severity (Depression 4.0; anxiety 6.0) Risk factors of psychological distress: Age ≥60 years, female, suburban residence, body mass index (<18.5), and stage III cancer, marital status of single or divorced. Greater self-efficacy was associated with milder symptoms severity and less symptom interference with daily life. |

| Abu-Helalah et al.,(2014)46 | To examine psychological well-being in CRC survivors. | Cross-sectional design. Jordan |

241 survivors with CRC from outpatient clinics (colon 60%, rectal 23%, colon and rectal, 17.4%; 56.7 y.o; 47.7% females; 100% Jordanish) | -Psychological distress: HADS | -Stage I (10.9%), II (38%), III (38%), IV (13.1%) -Surgery (98%), CTx (88%), RTx (25%) |

Time to assess symptoms: After cancer treatments (specific time point was not addressed). Psychological distress: Depression severity 4.4, Anxiety severity 3.9. Of note, 5.4% of participants had severe anxiety and 5.4% of them had severe depression. |

| Gray et al. (2014)34 | To examine the risk factors and impacts of anxiety and depression. | Cross-sectional design. Scotland |

496 survivors with CRC from colorectal oncology and surgical outpatient clinics (colon 55%, rectal 32%; 66 y.o.; 45% females, 100% Caucasian European) | -Psychological distress: HADS | -Stage I &II (71%), III & IV (19%) -Surgery (91%), CTx (78%), RTx (97%), Stoma (31%) |

Time to assess symptoms: Less than 2 years from diagnosis, and after cancer treatments (specific time point was not addressed). Psychological distress: Depression severity 4.07, Anxiety severity 5.32. Risk factors of psychological distress: Poor self-reported cognitive functioning, bowel symptoms, poor physical and social functioning. Impacts of psychological distress: High negative life and emotional impact, difficulties, functional impairments. |

| Dunn et al. (2013)21 | To examine the risk factors and impacts of psychological distress. | Prospective longitudinal design. Australia |

1703 women with CRC from urban cancer (median 60 y.o. [range 20-80]; mean 40% females) | -Composite score of psychological distress: Brief Symptom Inventory-18 | -Cancer stage (55% 0-II/35% with III, IV) -Surgery (54%), Surgery+RTx or CTx (43%) |

Time to assess symptoms: At post diagnosis, 1, 2,3,4,5 years follow-up. Psychological distress: Percentages of overall psychological distress among all participants were 44% at T1, 40% at T3, and 42% at T6 (depression and anxiety frequency: 42% at T6 in both symptoms) Risk factors of higher psychological distress: Short-term survivorship (< 2 years) compared to long-term survivorship (<5 years), younger age, lower education, poor socioeconomic advantage, late disease stage and poor social support. |

| C. Fatigue (n = 6) | ||||||

| Agasi-Idenburg et al. (2017)35 | To identify and compare symptom clusters including fatigue | Cross-sectional design. Netherlands |

1698 survivors with CRC from cancer registry and 2 urban hospitals (colon 59%, rectal 42%; 65 y.o.; 45% females) | -Fatigue: Fatigue Assessment Scale. | -Stage I (46%), II (54%) -Surgery (63%), Surgery + RTx (27%), Surgery + CTx (5%), Surgery+CTx+ RTx (5%) |

Time to assess symptoms: Mean 5 to 10 years after diagnosis. Identified symptom cluster including fatigue: An emotional symptom cluster (anxiety, fatigue, and depression); a pain symptom cluster (pain and insomnia); and a dyspnea only cluster. Risk factors of fatigue: Psychological distress. |

| Wei & Li (2017)31 | To evaluate the relationship between fatigue and nutritional status after surgery | Cross-sectional design. China |

70 survivors with CRC after surgery from a tertiary hospital (colon 63%, colorectal 37%; 67 y.o.; 29% females; 100% Chinese) | -Fatigue: Cancer Fatigue Scale. | -Stage II (71%), III (26%), IV (3%) -Surgery (100%), CTx or RTx (0%) |

Time to assess symptoms: At 24 hours after surgery Fatigue: 100% survivors reported fatigue (20% with severe fatigue) after surgery. Severity of fatigue increased after surgery. Risk factors of fatigue: Previous nutritional status, low white blood cells and low serum calcium levels. |

| Vardy et al. (2016)28 | To examine the severity and duration of fatigue | Prospective-longitudinal design. Canada & Australia |

362 survivors with CRC from multiple cancer registries (colon 69%, rectal 31%; 59 y.o.; 37% females; 100% Caucasian) | -Fatigue: FACT-Fatigue | -Stage I (46%), II (77%), III (76%), IV (20%) -CTx (98%) |

Time to assess symptoms: At baseline before CTx. 6, 12, and 24 months after CTx. Fatigue: Frequency of fatigue at baseline (52%). This increased over time: 70% at 6 months, 44% at 12 months, 39% at 24 months. Mean severity of fatigue increased over time: 67 (baseline), 65 (at 6 months), 71 (at 12 months), 75 (at 24 months). Risk factors of fatigue: Baseline fatigue, receiving chemotherapy, cognitive and affective symptoms, poorer QOL at baseline, and comorbidities. Impacts of fatigue: Poor QOL, affective and cognitive symptoms. |

| Li, Liu & Lu(2014)23 | To examine fatigue in post-surgical CRC survivors | Prospective longitudinal design (baseline, 2 or 3 days after surgery, 3 weeks after surgery). China |

96 survivors with CRC from a tertiary cancer center (colon 56%, rectal 44%; 60 y.o.; 21% females; 100% Chinese) | -Fatigue: Cancer Fatigue Scale | -Stage I (13%), II (76%), III (4%) -Surgery (100%), CTx (92%) |

Time to assess symptoms: At 3 weeks after the surgery (20.4 ±3.3). Fatigue: Fatigue increased at after 2 or 3 days of surgery, then decreased 3 weeks after surgery (mean severity at 3 weeks: 20.4). Tailored intervention based on the survivors’ characteristics at different periods may be required to alleviate fatigue. |

| Thong et al. (2013)40 | To examine the fatigue in short-term and long-term CRC survivors | Cross-sectional design. Netherlands |

3739 survivors with CRC (short-term survivors < 5 years: n = 2320, long-term survivors ≥ 5 years: n = 1419) from CRC registries (colon 50%, rectal 50%; 70 y.o.; females 55%; ethnicities not specified) | -Fatigue: Fatigue Assessment Scale | -Stage I (30%), II (37%), III (28%), IV (5%) -Surgery (50%), CTx (1%), RTx (0.1%), Surgery + CTx or RTx (49%) |

Time to assess symptoms: Mean 6 years after diagnosis. Fatigue: Frequency of fatigue (39%), higher than the general population (n=338) (39% vs. 22%, p<0.0001). Short-term survivors (<5 years post-diagnosis) had the highest mean fatigue scores compared with long-term survivors (≥5 years post-diagnosis) or the normative population (21±7 vs. 20±7 vs. 18±5, p<0.0001, respectively). Risk factors of fatigue: Psychological distress, having primary cancers prior to CRC, Surgery, CTx, and RTx |

| Mota et al. (2012)37 | To examine the frequency and risk factors of fatigue. | Cross-sectional design. Brazil |

159 survivors with CRC from four CRC outpatient clinics (colon 70%, rectal 30%; 60 y.o.; 46% females; 65% Caucasian) | -Fatigue: Piper Fatigue Scale. | -Stage I (9%), II (22%), III (25%), IV (45%), Cancer in remission (34%) -CTx and/or RTx (95%). |

Time to assess symptoms: Mean 5 years after diagnosis Fatigue: 26.8% survivors with 5.8 mean score. Risk factors of fatigue: Depression, poor performance status, and sleep disturbances. |

| D. Body Image Distress (n = 4) | ||||||

| Reese et al. (2018)25 | To assess body image distress over time and risk factors and Impacts of body image. | Prospective design USA |

141 survivors with CRC from urban cancer center (colon 74%, rectal 26%; 69 y.o.; 42% females; 83% Caucasian) | -Body image distress: Body Image Scale | -Mean 2.5 years -Stage I (30%), II (36%), III (38%), IV (4%) -Surgery (94%), CTx (75%), RTx (32%) |

Time to assess symptoms: Baseline and 6 months follow-up. Body image distress: Severity (0-10): 6.7 for survivors with colon cancer, 9.9 for survivors with rectal cancer, 6.0 for men, 9.6 for women. Risk factors of body image distress: Rectal cancer, being female. Impacts of body image distress: Lower sexual relationship, depression, poor QOL. |

| Benedict et al. (2016)30 | To examine body image and its correlates. | Cross-sectional design. USA |

70 women with CRC from urban cancer center (69% rectal, 29% anal; 55 y.o.; 100% females; 79% Caucasian) | -Body image distress: EORTC-C38 | -Stage I (31%), II (14%), III (41%) -Surgery (73%), CTx (11%), RTx (1%), CTx+RTx (71%) |

Time to assess symptoms: Mean 4 years after diagnosis (specific time point was not addressed). Body image distress: Average body image scores (69.2) indicated impairment. 86% reported body image distress. Risk factors of body image distress: Younger age, lower global health status, and greater severity of symptoms. Impacts of body image distress: Poor sexual relationships and sexual functioning. |

| Bullen et al. (2012)20 | To investigate body image as a predictor of psychological symptoms and QOL in CRC survivors after surgery. | Prospective design. Australia |

38 survivors with CRC from pre-surgical clinics (59 y.o.; 50% females; Caucasian) | -Body image distress: Body Image Ideals Questionnaire | -Surgery (100%) |

Time to assess symptoms: At 3 months after surgery. Risk factors of body image distress: Pre-existing body image distress, having stomas. Impacts of body image distress: Psychological distress, poor QOL. |

| Sharpe et al., (2011)26 | To examine the effect of having a stoma on body image distress. | Prospective design. Australia |

79 survivors with CRC from 7 hospitals (66 y.o; 40% females; Caucasian) | -Body image disturbance: Body image scale | -mean 10 years after cancer diagnosis. -Surgery (100%), CTx (40%), RTx (5%). |

Time to assess symptoms:

At baseline right after the surgery: 6.7 (group with stoma, n = 34), 3.3 in group with non-stoma (n = 65), total mean (5.5 out of 0-30 scale). At 6 months follow-up: 11.3(group with stoma, n = 34), 2.8 in group with non-stoma (n = 65), total mean (7.0 out of 0-30 scale). Risk factors of body image distress: Body image distress increased over time in group with stoma. Impacts of body image distress: Psychological distress. |

| E. Cognitive Impairment (n = 2) | ||||||

| Sales et al., (2019)15b | To examine the cognitive function differences by CTx groups. | Prospective, design. Group with CTx (n = 22) versus non-CTx (n= 47). Brazil |

69 survivors with CRC from cancer center (100% colon and rectal; 62.5 y.o.; 39.7% females; 58.8% Caucasian) | -Self-reported cognitive complaint questionnaires. Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). |

-Stage II (63.8%), III (36.2%) -CTx (100%, fluorouracil and oxaliplatin) |

Time to assess symptoms: Baseline and at 12 months after CTx. but frequency, severity, risk factors and impacts of neuropathy were not specified. Associations of cognitive impairment at baseline (pre-CTx) and 12 months after CTx by CTx groups: Using linear mixed models, patients with CRC who received CTx presented with a decline in executive cognitive function after 12 months compared with patients without CTx. There was not association of cognitive function with Apolipoprotein E genotyping. |

| Vardy et al., (2014)17b | To examine the cognitive function differences by CTx groups. | Prospective, longitudinal, design. Group with CTx (n = 173) versus non-CTx (n= 116), and healthy controls (HCs) (n = 72). Canada & Australia |

289 survivors with CRC from multiple cancer centers (colon 67%, rectal 33%; 59 y.o.; 37% females; 100% Caucasian) | -Cognitive function: FACT-Cognitive, Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) using Global Deficit Score | -Stage I (17.3%), II (36.7%), III (44.3%) -CTx (100%): Oxaliplatin (46%), fluorouracil (31.2%) |

Time to assess symptoms: At 6, 12, and 24 months after CTx. Frequency of cognitive impairment: 39%, and 46% at 6 and 12 months, respectively in CRC groups with and without CTx, compared with 6% and 13% in HCs. *Differences between CTx group (32%) vs. non-CTx group (16%) at 6 months, but not at 12 and 24 months. Severity of cognitive impairment (GDS more than 0.5 indicates impairment): 0.62, 0.57, 0.63, 0.56 (at baseline ‘pre-CTx’, 6, 12, and 24 months). This was significantly higher than HCs. Risk factors of cognitive impairment: Group, time, group-time interaction, female sex, and non-English primary language, previous higher cytokine levels, psychological distress, fatigue. Impacts of cognitive impairment: Psychological distress, fatigue, and poor QOL. |

| F. Insomnia (n = 1) | ||||||

| Coles et al. (2018)16b | To assess sleep disturbance and its correlates. | Cross-sectional design. USA |

613 survivors with CRC from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program cancer registries (colon 61%, rectal 39%; 62 y.o.; 53% females; 55% Caucasian, 20% African-American) | -Sleep: Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) | -Stage I (29%), II (31%), III (40%) -CTx (55%), RTx (19%) |

Time to assess symptoms: Mean 10 months after diagnosis. Mean scores of PROMIS: Sleep (50) Risk factors of sleep disturbances: Pain, anxiety, fatigue, multiple comorbid conditions, and retirement. Sleep disturbance screening may be warranted in individuals diagnosed with CRC. |

Note.

Abbreviation: CRC, colorectal cancer; CTx, Chemotherapy; EORTC, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; FACT, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; QOL, quality of life; RTx, Radiotherapy; YO, years old.

Only data available in the selected studies are presented in the table.

Denotes the studies excluded in meta-analyses (n = 3).

Study Characteristics

Two-thirds of the studies (N = 21) had cross-sectional designs, while 14 studies had longitudinal, prospective designs (Tables 1 and 2). The longitudinal studies measured symptoms at baseline and after cancer treatments. In these longitudinal studies,15,17-29 overall, symptoms worsened over time (the longest follow-up: 2 years after chemotherapy).17 Studies included in our review were conducted in various countries of the 35 studies, including the United Kingdom (U.K.) (N = 9), U.S. (N = 9), Australia (N = 8), and Asia (N = 4, including 1 in Taiwan and 3 in China). The majority of participants (N = 24 out of 35 studies) were male, while 2 studies included only female participants.27,30 The age range of research participants across all the studies was 50 to 70 years old, with an average age of 63.

The timeframe for assessment ranged from 24 hours after treatment31 to 11 years after cancer diagnosis.32 The most common time point to assess symptoms was between 6 months and 2 years following treatment.15-17,22,24-26,28,33,34 Patient symptomology was also assessed an average of 3 to 6 years after initial cancer diagnosis.2,5,18,21,27,30,35-42 In 6 studies, the time point for symptom assessment was not specified.30,34,43-46 In symptom dimensions (i.e., frequency, severity, and distress), frequency and/or severity were used in 34 studies, except for one study.15 In 14 studies,18,19,28-30,32,34,36-38,40,41,44,46 both severity and frequency were reported while either severity or frequency was reported in other 21 studies. A variety of validated tools were used to measure CRC symptoms in the 35 studies. The most frequently used tool was the European Organization into Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) instruments (e.g., EORTC-C30, C38, C29, or Chemotherapy Induced Peripheral Neuropathy [CIPN20]) in 8 studies.2,5,22,30,32,33,39,41 The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was the second most common assessment tool, used in 6 studies (Tables 1 and 2).18,24,34,43,44,46

Symptom Experiences

Multiple symptoms.

Six of the 35 studies2,5,22,24,33,47 assessed overall symptomology, including physical and psychological symptoms (Table 1). GI symptoms, psychological distress, fatigue, or insomnia were evaluated. GI symptoms and fatigue were the major adverse symptoms reported among study participants. Several GI symptoms — including abdominal pain, diarrhea, constipation, fecal incontinence, blood and mucus in stool, and nausea and/or vomiting — frequently occurred following cancer treatments such as surgery or chemotherapy.2,5,22,24,33,47 Following chemotherapy, other reported symptoms included pelvic floor pain,5 stomach aches, pain in the rectum, perianal skin irritation and soreness were reported after rectal surgery.24

Although we excluded studies primarily focused on sexual and urinary symptoms given our exclusion criteria, 2 studies assessing multiple patient symptoms5,33 reported findings on urinary and sexual dysfunction. CRC survivors experienced moderate urinary problems and mild sexual dysfunction following surgery.5,33 These symptoms were also seen in 1,215 long-term CRC survivors more than 5 years after diagnosis, with a 30% frequency of urinary problems and a 20% occurrence of sexual dysfunction.5

Single symptom.

Twenty-nine of the 35 studies focused primarily on single symptoms experienced in CRC survivors (Table 2). These included: peripheral neuropathy (N = 9, Table 2A); psychological distress such as anxiety and depression (N = 7, Table 2B); fatigue (N = 6, Table 2C); body image distress (N = 4, Table 2D); cognitive impairment (N = 2, Table 2E); and insomnia (N = 1, Table 2F).

Meta-Analyses of Symptoms After Cancer Treatments

Heterogeneity among studies.

Overall heterogeneities in each symptom subgroup were high, with I2 > 75% in both pooled frequency and severity analyses, thus overall, random-effects model results were used (Table 3). However, we chose fixed-model results to determine frequency of body image distress, and for assessing severity of fecal incontinence, embarrassment with bowl movement, abdominal pain, appetite loss, nausea and/or vomiting, and sore mouth and tongue.

Table 3.

Meta-Analyses of Symptom Frequency and Severity (Pooled Estimates and Heterogeneity of Included Articles per Symptom).

| Meta-analysis | Symptom | Number of studies per symptom |

Pooled mean estimate (95% CI)c |

Heterogeneity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q-value | df.(Q) | I2, % | p-value | ||||

| Pooled Mean Frequencya (of each 10 symptom) | Body image distress | 2 | 78.5 (75.6, 81.0) | 2.262 | 1 | 55.78 | .133 |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 8 | 61.8 (37.1, 81.6) | 335.63 | 7 | 97.91 | .000 | |

| Fecal incontinence | 2 | 52.3 (18.5, 84.1) | 262.51 | 1 | 99.61 | .000 | |

| Bloating | 2 | 45.4 (9.1, 87.3) | 408.44 | 1 | 99.75 | .000 | |

| Fatigue | 5 | 38.1 (33.3, 43.2) | 25.64 | 4 | 84.40 | .000 | |

| Constipation | 2 | 34.3 (2.5, 91.5) | 537.83 | 1 | 99.81 | .000 | |

| Diarrhea | 2 | 32.7 (2.0, 92.0) | 538.75 | 1 | 99.81 | .000 | |

| Abdominal pain | 3 | 31.4 (6.7, 74.6) | 497.26 | 2 | 99.59 | .000 | |

| Anxiety | 6 | 26.8 (15.6, 42.0) | 415.36 | 5 | 99.41 | .000 | |

| Depression | 7 | 22.4 (14.8, 32.6) | 417.52 | 6 | 98.91 | .000 | |

| Pooled Mean Severityb (of each 15 symptom) | Fatigue | 7 | 50.14 (45.07, 55.21) | 453.99 | 6 | 98.89 | .000 |

| Insomnia | 2 | 39.93 (14.57, 65.28) | 19.50 | 1 | 94.87 | .000 | |

| Body image distress | 6 | 36.45 (28.83, 44.06) | 518.44 | 5 | 99.03 | .000 | |

| Anxiety | 8 | 27.67 (23.49, 31.67) | 151.62 | 7 | 95.02 | .000 | |

| Depression | 8 | 23.78 (19.83, 27.74) | 164.31 | 7 | 95.72 | .000 | |

| Fecal incontinence | 2 | 21.11 (19.98, 22.35) | 3.03 | 1 | 67.01 | .082 | |

| Embarrassment with bowel movement | 2 | 19.83 (18.42, 21.24) | 0.66 | 1 | 0.00 | .414 | |

| Abdominal pain | 2 | 18.21 (15.48, 20.95) | 0.03 | 1 | 0.00 | .853 | |

| Diarrhea | 3 | 17.78 (−6.07, 41.64) | 1191.80 | 2 | 99.83 | .000 | |

| Appetite loss | 2 | 14.70 (13.65, 15.76) | 0.01 | 1 | 0.00 | .892 | |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 7 | 14.19 (11.25, 17.13) | 68.93 | 6 | 91.29 | .000 | |

| Nausea and/or vomiting | 2 | 13.31 (12.48, 14.15) | 0.12 | 1 | 0.00 | .729 | |

| Sore mouth and tongue | 2 | 11.24 (10.66, 11.83) | 3.69 | 1 | 72.91 | .055 | |

| Blood and mucous in stool | 2 | 7.04 (−2.46, 16.54) | 47.86 | 1 | 97.91 | .000 | |

| Constipation | 2 | 6.16 (−1.45, 13.79) | 4.25 | 1 | 76.47 | .039 | |

Note. A random-effects model was preferred if heterogeneity is expected (I2 > 75%); otherwise, we chose a fixed-effects model.

Symptoms data in the row were based on rank.

on a 0-100% scale.

on a 0-100 point scale.

pooled frequency and severity of symptoms were computed with weighted effect size and standard errors, along with 95% confidence interval (CI).

Abbreviation. CI, confidence interval. df., degree of freedom.

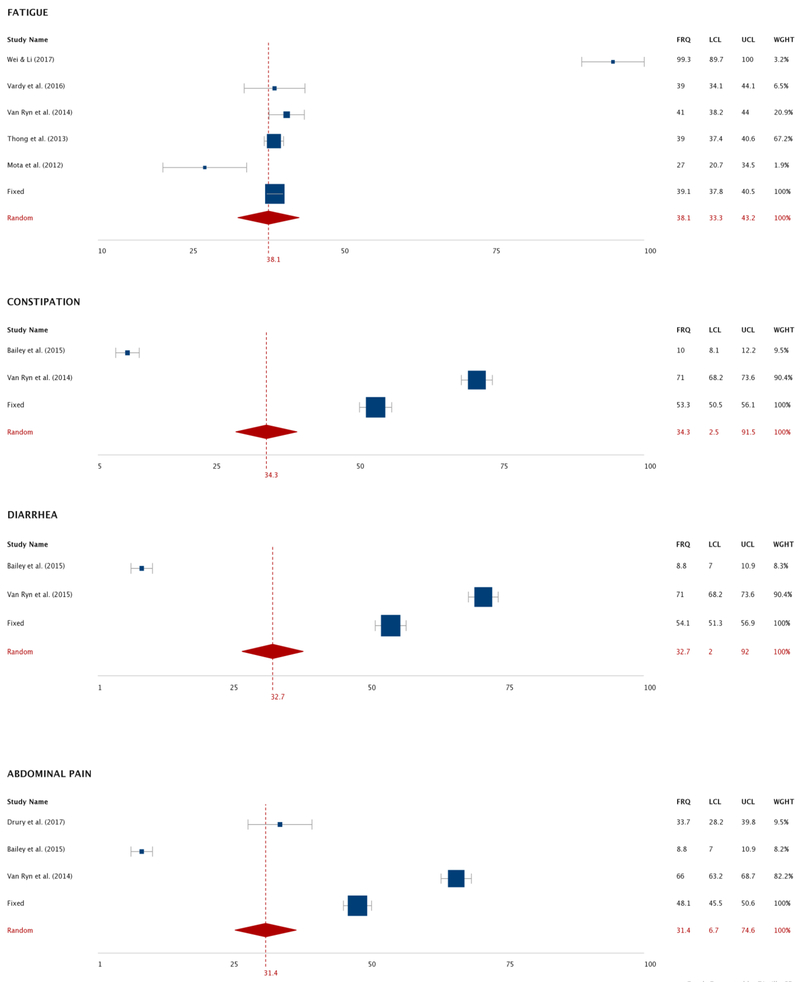

Pooled mean frequency of symptoms.

As seen in Figure 3, a total of 22 studies were included in the pooled analysis of system frequency.2,5,18,19,21,27-32,34,36-42,44,46,47 Ten post-cancer treatment symptoms were analyzed: body image distress, peripheral neuropathy, fecal incontinence, bloating, fatigue, constipation, diarrhea, abdominal pain, anxiety and depression (Table 3, Figure 3). Among these symptoms, the pooled mean frequency was highest for body image distress (78.5%, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 75.6 to 81.0), followed by peripheral neuropathy (61.8%, 95% CI: 37.1 to 81.6). Approximately one-third of post-treatment patients reported GI symptoms of constipation, diarrhea, or abdominal pain, while about half experienced fecal incontinence or bloating.

Figure 3.

Forest Plot of Pooled Frequencies of Symptoms in Colorectal Cancer Survivors after Cancer Treatments via Meta-Analyses.

Note. Random effect model was used except for body image distress.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence intervals; FRQ, frequency; LCL, Low confidence interval limit; UCL, upper confidence interval limit; WGHT, weight of each study.

Pooled mean severity of symptoms.

As seen in Figure, a total of 22 studies were included in the pooled analysis of symptom severity.18-20,22-26,28-30,33,34,36-38,40,41,43-46 Fifteen symptoms were included: fatigue, insomnia, body image distress, anxiety, depression, fecal incontinence, embarrassment with bowel movements, abdominal pain, diarrhea, appetite loss, peripheral neuropathy, nausea and/or vomiting, sore mouth and tongue, blood and mucus in stool, and constipation. Following cancer treatments, fatigue was the most severe symptom (pooled mean severity = 50.1, 95% CI: 45.1 to 55.2), followed by insomnia (mean = 39.9, 95% CI: 14.6 to 65.3) and body image distress (mean = 36.4, 95% CI: 28.8 to 44.1) on a 0-100 scale (Table 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest Plot of Pooled Severities of Symptoms in Colorectal Cancer Survivors after Cancer Treatments via Meta-Analyses.

Note. Fixed effect model was used for fecal incontinence, embarrassment with bowel movement, abdominal pain, appetite loss, nausea and/or vomiting, and sore mouth and tongue. Pooled mean severity data on a 0-100 scale.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence intervals; FRQ, frequency; LCL, Low confidence interval limit; UCL, upper confidence interval limit; WGHT, weight of each study.

Potential Risk Factors of Symptoms

Risk factors related to symptom development were extracted from the original studies (Tables 1 and 2). Being female was significantly associated with the severity of various symptoms, including GI symptoms,2 psychological distress,18,43,44 body image distress,25,30 and fatigue.28 Certain cancer treatments were positively associated with severe symptoms.2,15,19,22,29,32,36,38-42,47 For example, receiving oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy was significantly associated with severity of peripheral neuropathy in CRC survivors. 19,29,32,36,38,39,41,42 Younger patient age or younger age at diagnosis were strong predictors of long-term symptom severity in CRC survivors.2,5,22,30,47 Individuals diagnosed at a younger age suffered higher levels of emotional distress and body image distress, while those diagnosed at an older age experienced frequent sexual and urinary dysfunction.5 Low education,18,21,34 low self-efficacy,43 and unmarried or single patients18,22,34,43 were more likely to experience severe symptoms, including psychological distress. Patients with late stages of CRC (stage III or IV),43,44,47 multiple comorbidities including psychological disorders, 16,35,37,40,41,45 and poor physical and social functioning,16,18,34,37,43,45 also reported more severe symptoms.

The experiences of having ostomies were associated with various GI symptoms (e.g., fecal incontinence, unintentional fecal release), psychological distress (e.g., embarrassment with bowel movements, anxiety concerning a stoma), fatigue, and sexual distress.5,20,22,33 Poor nutritional levels, low blood cell counts and serum calcium levels were positively associated with fatigue.31 Symptoms were often inter-related. For example, psychological distress, poor sleep quality, and fatigue were associated,23,28,31,35,37,40,48 while GI symptoms and psychological distress were associated with body image distress.30

Potential Impact of Symptoms

Various potential impacts of CRC symptoms were identified in 35 studies. Overall, poor physical, emotional, and social QOL, interferences with daily life, caregiver burdens, and financial burdens emerged (Tables 1 and 2). Poor QOL was the most frequently reported impact of adverse symptomology.2,17,20,22,25,28,32,33,39,41,45 GI symptoms were associated with lower physical activity in long-term cancer survivors.2,24 Adverse symptoms also negatively impacted sexual functioning and relationships.5,30,33,44 For example, GI symptoms (e.g., fecal incontinences, abdominal bloating), embarrassment with bowel movements, having a stoma, and sexual dysfunction were associated with poor sexual relationships with partners. Acute or chronic adverse symptoms also took an emotional toll, increasing depression, fatigue, and anxiety.20,25,28 The symptom burden also limited social functioning and interactions with family, friends, and community.2,18,34 Patient caregivers also suffered in a variety of ways. Cancer-related symptoms were associated with caregivers’ emotional distress, low physical functioning, poor general health, and low overall QOL.22,33 These individuals often experienced increased depression, fatigue, insomnia, anxiety, and physical tiredness related to their caregiving burdens. Finally, adverse CRC symptoms increased ongoing financial difficulties and concerns for caregivers and in CRC survivors alike.24,44

DISCUSSION

This is the first systematic review and meta-analyses we are aware of that comprehensively addresses symptom experiences in CRC survivors after cancer treatments. Our review extends the existing literature by synthesizing the findings of individual studies into a detailed overview of symptomology, including risk factors and impacts of symptoms in this vulnerable population. A majority of the included 35 studies focused on a single symptom rather than assessing multiple symptoms. Findings indicate many CRC survivors experienced persistent adverse symptoms following cancer treatments. Our meta-analyses showed that body image distress, and peripheral neuropathy were the most prevalent, while fatigue and insomnia were the most severe. We also found that GI symptoms and psychological distress were also major symptoms. Patient factors associated with worse symptoms include: younger age, female gender, cancer stage III or IV at diagnosis, lack of family and social support, oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy, and having a stoma. Such symptoms negatively affect physical and emotional status, social functioning and relationships, QOL, caregivers’ physical and emotional health, and financial status. Our research documents the importance of long-term clinical management persistent negative symptoms after cancer treatment ends.

Given that a multidimensional approach is needed for effective symptom management, the Symptom Management Model8 offers guidance for helping CRC survivors who experience a variety of unremitting symptoms. Our findings are supported from the Symptom Management Model, by confirming that optimal symptom management depends on understanding the dynamics and interplay of these various health components. Our findings may help researchers understand major risk factors of symptom burden, and develop effective symptom management strategies CRC survivors within this holistic conceptual model.

Our meta-analysis of symptom frequency and severity across the 32 out of 35 studies revealed that body image distress was a prevalent and severe symptom in CRC survivors (pooled frequency:78.5%, ranked 1st; pooled severity: mean 36.5, ranked 3rd) among symptoms included in our analyses. A higher degree of body image distress was associated with experiences with having past or current stomas.25,26,30 A qualitative study of CRC survivors found having a stoma increased body image distress, which in turn led to physical and emotional problems, low self-esteem, social isolation, loss of appetite, food restriction, uncertainty, limited social functioning and interaction, impaired sexual relationships and intimacy with partners, and poor QOL.49 In this qualitative study, compared to other cancer-related symptoms, body image distress was rarely discussed between clinicians and CRC survivors.49 Thus, it is needed for healthcare providers to engage with patients on this issue continuously both before and after cancer treatments, specifically stoma surgery.

In our meta-analyses, fatigue was the most severe symptom (mean = 50.1) with a pooled frequency 38.1% (ranked 5th) among symptoms included in our analyses. Fatigue is also frequent and severe symptom experienced after treatment for other cancer types, including leukemia and breast, lung, prostate, and ovarian cancers.48 Notably, low hemoglobin and poor nutritional status,31 and anemia and digestive hemorrhages24 contribute to fatigue in CRC survivors. Disease-related digestive hemorrhages, hemolysis, and increased cytokines are potential causes of impaired iron metabolism that can cause anemia in CRC survivors.24 The loss of nutrients can also contribute to fatigue in CRC survivors.24 This is an important clinical consideration because fasting and hyper-metabolism may occur after colorectal surgery.31 Chemotherapy-related side effects, such as anorexia, nausea, and vomiting can also increase malnutrition and associated fatigue in CRC survivors.48 Cancer-related inflammation, neuroendocrine alterations, and autonomic nervous system dysregulation are also related to fatigue.48 This suggests that screening and treating anemia, and nutritional status may reduce fatigue in CRC survivors. Further research is also needed on cancer-related nutritional deficiencies, anemia, and biological mechanisms to better understand, assess, and treat fatigue in CRC survivors.

Our meta-analyses found that mild GI symptoms were frequently reported in CRC survivors after cancer treatments (Figures 3 and 4). Various GI complications reported were abdominal pain, fecal incontinence, bloating, constipation, diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea and/or vomiting, blood and mucus in stool, and appetite loss. Such symptoms can directly result from certain cancer treatments. In addition, a colon or rectal tumor itself can cause physiological bowel problems such as malabsorption, GI tract inflammation, and motility disorders.6 Our findings suggest that the awareness of GI symptoms may help both predict the risk of CRC and guide post-treatment clinical management for long-term CRC survivors.

In several cases we found discordances in rank orders of several symptoms based on frequency versus severity. For example, peripheral neuropathy was the second most prevalent among 10 symptoms analyzed (frequency: 61.8%), but its severity was only mild (14.2, ranked 11th out of 15 symptoms). Similarly, the pooled frequency of anxiety and depression ranked 9th, and 10th respectively, while their pooled severities ranked 4th, and 5th respectively (Table 3). These findings highlight the importance of assessing various symptom dimensions (i.e., severity, frequency) following cancer treatments, because that a patient is not complaining about a severe condition does not mean it is nonexistent or is not negatively impacting their overall wellbeing.

In our meta-analyses we found that insomnia and psychological distress were also major symptoms in CRC survivors. Two studies of our review reported that psychological distress, insomnia, and fatigue often co-occur as a symptom cluster in CRC survivors, with a cluster analysis,22 and a principal component analysis.35 This finding is consistent with previous symptom cluster studies related to other types of cancer. Fatigue, depression, anxiety, and insomnia often occur together in breast, lung, prostate, and ovarian cancer.6 A recent study emphasizes the importance of the symptom cluster approach in identifying distinct symptom phenotypes in cancer patients and providing clinical treatments that targets co-occurring symptoms.50 It is important for clinicians to be knowledgeable about CRC symptom clusters post-chemotherapy and apply it to clinical practice because it may enable them to identify symptoms that are overlooked or hidden and effectively anticipate other symptoms that might likely occur during the assessment.

Although our analysis excluded systematic reviews focused on sexual and/or urinary symptoms,10,11 our review revealed that mild-to-moderate sexual or urinary symptoms were reported after cancer treatments.25,30,33,44 A previous review of sexual dysfunction studies reported that approximately 50% of female and 5% to 88% of male CRC survivors reported sexual dysfunction after radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or surgery.11 Another systematic review examining both sexual and urinary dysfunction,10 revealed between 22% and 76% of CRC survivors across studies experienced these symptoms. Both these symptoms were associated with stomas, cancer treatment complications, tumor location in the lower rectum or anus, psychological distress, older age, poor QOL, and altered body image after cancer treatments.10,11 Two articles included in our analyses confirmed the impact of body image distress on poor sexual functioning and QOL.25,30 It is therefore important for researchers and clinicians to bear in mind the interplay of multiple symptoms when addressing urinary and/or sexual dysfunction in long-term CRC survivors.

Multiple predisposing factors—younger patient age, younger age at diagnosis, female gender, advanced cancer stage at diagnosis, and lack of family and social support—were associated with worse symptom experiences. Rasmussen et al. (2015) reported that older CRC patients experienced less severe, frequent, and prolonged adverse symptoms in general than younger CRC patients.4 Symptoms in older CRC patients were also less likely to be associated with cancer treatments compared to younger patients.4 Several possible explanations may exist for different symptom experiences by age. Rasmussen et al. (2015)4 noted that younger-aged or younger-onset survivors were more likely to undergo surgery and chemotherapy than older patients. Given this treatment tendency, it is not surprising younger patients may report more treatment-related symptoms, while symptoms in older CRC patients may be associated more with the aging process than cancer. In addition to age, cancer patients from different sociodemographic and clinical characteristics may appraise their symptoms differently.49

Our review revealed that negative symptom experiences in CRC survivors resulted in poor QOL, limited social engagement, and multi-level distress for caregivers. Of note, caregivers for CRC survivors often reported feeling depressed and stressed because of insufficient training in how to care for the patient, financial burdens, lack of social resources, or difficulty in balancing multiple caregiving roles.49 Importantly, despite the extensive involvement of family members in caring for CRC survivors, little research exists on these caregivers’ daily experiences, demands, challenges, and needs in this patient group.49 Healthcare professionals need to be aware of this often overwhelming family dynamic and provide caregivers with referrals to community resources to ease their burden.

The current study has several limitations. First, the majority of studies in this review were conducted in the U.K. or U.S. Results are not necessarily generalizable to other countries, particularly those with different oncology healthcare systems or different cultural views towards symptom experiences in cancer survivors. Second, it is unknown whether symptoms differ according to variable factors such as time after treatment until symptom onset, or time from cancer diagnosis to treatment. Third, while this review highlights risk factors for common CRC symptoms and outcomes, it cannot explain the exact nature and direction of the association between risk factors, symptoms, and outcomes. This is because most of the included studies had cross-sectional designs. Fourth, there were inconsistencies in the assessment and reporting of symptoms across the 35 studies. Different studies used various symptom dimensions, scoring ranges, instruments, scoring interpretations, and periods to assess symptoms. Such inconsistencies and gaps in symptom assessment made it difficult to conduct a meta-analysis and compute a pooled mean severity and frequency for several symptoms from such disparate and incompatible data. In the case of several symptoms (e.g., cognitive impairment), there were not two compatible studies to include in our meta-analyses.

More research are suggested to assess each individual symptom including cognitive impairment, GI symptoms, and insomnia. The many burdens associated with long-term caregiving duties are another crucial area for future inquiry. To better understand persistent symptoms in CRC survivors, researchers must devise standardized assessment tools and methods, which will guide future tailored symptom interventions for patients with symptoms, who are at high risk. A consensus also is needed on the condition of symptom assessment (i.e., measurement, time to assess symptoms, symptom dimensions). Lastly, given our primary aim of this review, we only focused on risk factors of symptoms, under the concept of symptom management strategies in the Symptom Management Model. Thus, future research is needed to further explore other aspects of symptom management strategies (e.g., who delivers, what, and how to deliver) in CRC survivors. Such research can foster the design of tailored symptom management protocols for CRC survivors at high risk of symptom burden.

Clinical Implications

CRC survivors in our review often reported multiple concurrent, and persistent adverse symptoms that have impacted their physical, social, and psychological QOL. Study findings can help nurses and oncologists perform more informed patient assessments following cancer treatments and provide more thorough symptom management for long-term survivors. Many patients would likely benefit from a referral for CRC-specific counseling to address common concerns like body image distress, fatigue, GI symptoms, psychological distress, and poor QOL. Our findings inform patients and caregivers to consider an opportunity to strategize with healthcare providers to assure optimal symptom management and arrange for needed community support services.

CONCLUSION

CRC survivors experience multiple adverse symptoms which often continue after cancer treatment ends. Our meta-analyses revealed that body image distress, fatigue, GI symptoms, psychological distress are major problems for this population group. Multiple risk factors contribute to adverse symptomology including younger patient age, female gender, and lack of family and social support. Unrelieved CRC symptoms are linked to psychological distress, and financial burdens, decreased QOL and social functioning, and caregivers’ physical and emotional difficulties. There are analysis barriers related to inconsistent or incomplete data in existing studies that need to be overcome in future research. It is necessary to reach a methodological consensus on CRC symptom assessment so that investigators can obtain a conclusive understanding of the challenges faced by survivors following treatment. Future research is warranted to develop individualized symptom management strategies for CRC survivors at high risk of symptom burden.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement:

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows. CH is involved in all part of this manuscript as a first author: designed the research questions, aims, introduction, methods, data synthesis, results and discussion part. GSY is involved in introduction, and discussion as a second author.

KS guided overall study aims, study design and methods and discussion writing, and reviewed all manuscript works as a senior author. The authors thank Mr. Ezra Ochshorn for English Language editing services.

Funding:

CH is supported in part by the NIH NCI BCPT (Biobehavioral Cancer Prevention and Control) Cancer Fellowship Training Program at the University of Washington, Dept. Public Health; and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, Grant Nr. T32 CA092408-27. G.S.Y. is supported in part by the NIH/NINR F32NR018367.

Abbreviations:

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- QOL

quality of life

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Claire J. Han, University of Washington, Department of Public Health, Seattle, WA; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Cancer Prevention Program, Seattle, WA.

Gee S Yang, University of Florida, College of Nursing, Gainesville, FL.

Karen Syrjala, University of Washington, Department of Public Health, Seattle, WA; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Cancer Prevention Program, Seattle, WA.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(1):7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drury A, Payne S, Brady AM. The cost of survival: an exploration of colorectal cancer survivors' experiences of pain. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(2):205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tantoy IY, Cataldo JK, Aouizerat BE, Dhruva A, Miaskowski C. A Review of the literature on multiple co-occurring symptoms in patients with colorectal cancer who received chemotherapy alone or chemotherapy with targeted therapies. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39(6):437–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rasmussen S, Larsen PV, Sondergaard J, Elnegaard S, Svendsen RP, Jarbol DE. Specific and non-specific symptoms of colorectal cancer and contact to general practice. Fam Prac. 2015;32(4):387–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey CE, Tran Cao HS, Hu CY, et al. Functional deficits and symptoms of long-term survivors of colorectal cancer treated by multimodality therapy differ by age at diagnosis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19(1):180–188; discussio 188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrington CB, Hansen JA, Moskowitz M, Todd BL, Feuerstein M. It's not over when it's over: long-term symptoms in cancer survivors--a systematic review. Int J Psych Med. 2010;40(2):163–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Blarigan EL, Fuchs CS, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Association of survival with adherence to the American Cancer Society Nutrition and Physical Activity Guidelines for Cancer Survivors after colon cancer diagnosis: the CALGB 89803/Alliance trial. JAMA oncology. 2018;4(6):783–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dodd M, Janson S, Facione N, et al. Advancing the science of symptom management. J Adv Nurs. 2001;33(5):668–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lampropoulos P, Rizos S, Tsigris C, Nikiteas N. Sexual and urinary dysfunctions following laparoscopic resection for rectal cancer. Hellenic J Surg. 2011;83(6):6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Traa MJ, De Vries J, Roukema JA, Den Oudsten BL. Sexual (dys)function and the quality of sexual life in patients with colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(1):19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clisby N, Charnock D. DISCERN/CASP Workshops 2000 Final Project Report. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Institute of Health Sciences; In: Oxford; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.George BJ, Aban IB. An application of meta-analysis based on DerSimonian and Laird method. In: Springer; 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han CJ, Yang GS. Fatigue in irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of pooled frequency and severity of fatigue. Asian Nurs Res. 2016;10(1):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sales MVC, Suemoto CK, Apolinario D, et al. Effects of adjuvant chemotherapy on cognitive function of patients with early-stage colorectal Cancer. Clin Colon Cancer.. 2019;18(1):19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coles T, Tan X, Bennett AV, et al. Sleep quality in individuals diagnosed with colorectal cancer: Factors associated with sleep disturbance as patients transition off treatment. Psych Oncol. 2018;27(3):1050–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vardy J, Dhillon HM, Pond GR, et al. Cognitive function and fatigue after diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(12):2404–2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mols F, Schoormans D, de Hingh I, Oerlemans S, Husson O. Symptoms of anxiety and depression among colorectal cancer survivors from the population-based, longitudinal PROFILES registry: prevalence, predictors, and impact on quality of life. Cancer. 2018;124(12):2621–2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Argyriou A, Velasco R, Briani C, et al. Peripheral neurotoxicity of oxaliplatin in combination with 5-fluorouracil (FOLFOX) or capecitabine (XELOX): a prospective evaluation of 150 colorectal cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(12):3116–3122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bullen TL, Sharpe L, Lawsin C, Patel DC, Clarke S, Bokey L. Body image as a predictor of psychopathology in surgical patients with colorectal disease. J Psych Res. 2012;73(6):459–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dunn J, Ng SK, Holland J, et al. Trajectories of psychological distress after colorectal cancer. Psych Oncol. 2013;22(8):1759–1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gosselin TK, Beck S, Abbott DH, et al. The Symptom Experience in Rectal Cancer Survivors. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52(5):709–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li SX, Liu BB, Lu JH. Longitudinal study of cancer-related fatigue in patients with colorectal cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Pev. 2014;15(7):3029–3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin KY, Denehy L, Frawley HC, Wilson L, Granger CL. Pelvic floor symptoms, physical, and psychological outcomes of patients following surgery for colorectal cancer. Physiother Theory Pract. 2018;34(6):442–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reese JB, Handorf E, Haythornthwaite JA. Sexual quality of life, body image distress, and psychosocial outcomes in colorectal cancer: a longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(10):3431–3440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharpe L, Patel D, Clarke S. The relationship between body image disturbance and distress in colorectal cancer patients with and without stomas. J Psych Res. 2011;70(5):395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Tworoger SS, Poole EM, et al. Psychological symptoms and subsequent healthy lifestyle after a colorectal cancer diagnosis. Health Psychol. 2018;37(3):207–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]