Extensins are a subfamily of the plant cell-wall hydroxyproline (Hyp)-rich glycoproteins (HRGPs). Castilleux et al. (2020) take a genetic approach to understanding the roles of extensin glycosylation in plant–microbe interactions by comparing the responsivity or susceptibility of four Arabidopsis mutants associated with extensin arabinosylation and wild-type (WT) plants to a peptide from bacterial flagella and the oomycete pathogen Phytophthora parasitica. The protein backbones of extensins contain the characteristic repetitive SerHyp4 glycosylation motifs and ValTyrLys or TyrXTyrLys crosslinking motifs. Although a quantitatively minor component of the plant cell wall, extensins play important roles in many aspects of plant growth, development and defence. Evidence shows that lack of the AtEXT3 gene leads to severe defects in development of Arabidopsis roots, shoots and hypocotyls (Cannon et al., 2008). The function of AtEXT3 is attributed to the perfect alignment of the repetitive crosslinking motifs and subsequent Tyr-crosslink between different AtEXT3 molecules to form a rigid extensin network within the cell wall. Velasquez et al. (2011) provided evidence that the ability of extensin to form a functional crosslinked network is dependent on proline-hydroxylation and subsequent Hyp-O-arabinosylation. With reduced extensin arabinosylation, Arabidopsis root hair lengths were significantly decreased. Additionally, recent in vitro studies have revealed that both Ser-O-galactosylation and Hyp-O-arabinosylation determine the rate of extensin crosslinking and hence the efficiency of extensin network formation (Chen et al., 2015). Thus, correct arabinosylation of extensins is essential for their in vivo functions.

Extensins are actively involved in plant root defence. They are highly expressed in roots of most plant species, especially when roots are under attack by microbes. Immunolocalization shows that extensin epitopes are most abundant in the cell walls of roots, especially root caps, border cells and border-like cells, and in the interface between root cells and microbes. Extensins may strengthen the cell wall through peroxidase-catalysed crosslinking of tyrosine residues in extensin crosslinking motifs. Importantly, elevated levels of peroxidase and hydrogen peroxide were detected at root–microbe interfaces, presumably leading to efficient catalysis of oxidative radical crosslinking of extensins (Shailasree et al., 2004). The subsequently formed extensin network and its associated wall polysaccharides, such as pectins and arabinogalactan-proteins (AGPs), would reinforce the cell wall and limit the colonization by pathogens (Figure 1). This is supported by the result that Arabidopsis overexpressing the EXT1 gene showed fewer symptoms after infection with Pseudomonas syringae than WT plants (Wei and Shirsat, 2006).

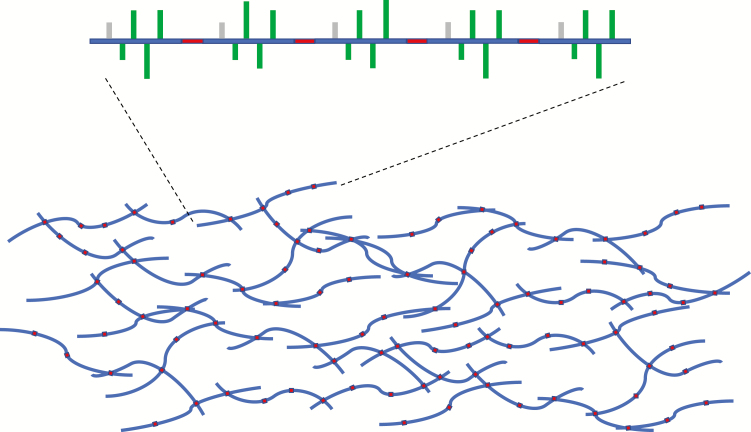

Fig. 1.

Extensin and an extensin network. The top cartoon shows an extensin molecule with five SerHyp4 glycosylation motifs (green bar: arabinosides, grey bar: galactose) and four crosslinking motifs (in red). The bottom model presents a highly crosslinked extensin network, which interlocks wall polysaccharides and AGPs (not shown in the figure) to form a rigid cell wall. When the wall is under pathogen attack, more extensins are deposited on to the wall, which would theoretically, in the presence of peroxidase and hydrogen peroxide, form either a thicker or a more densely crosslinked extensin network, or both. A tighter cell wall would help the cell to defend against external pathogens. As shown by Castilleux et al. (2020), correct proline-hydroxylation and Hyp-O-arabinosylation of extensins are crucial for the formation of such an important line of defence.

The mutant genes investigated by Castilleux et al. (2020) in four Arabidopsis mutants include P4H2 for proline-4-hydroxylation, RRA1 and RRA2 for addition of an arabinosyl residue onto Hyp-O-Ara, and XEG113 for transfer of an arabinosyl residue onto Hyp-O-Ara2. They found that the extensin epitopes, recognized by anti-extensin monoclonal antibodies LM1, JIM11, JIM12 and JIM20, respectively, in the root of mutants and WT plants responded differently to Flg22 elicitation. More interestingly, they observed that zoospores of the oomycete pathogen Phytophthora parasitica were more abundant over the rra2 and xeg113 mutant roots than WT 3 h after inoculation, suggesting that without arabinosylation of the second or third arabinose on Hyp-O-arabinosides the corresponding cell wall is more susceptible to pathogen invasion. Glycosyl composition and linkage analyses showed significant increases of 3-linked Gal in rra2 and xeg113 mutant roots compared to WT, indicating that AGPs (rich in 3-Gal) might contribute significantly to the mutant wall reorganization after infection.

To further support the proposed function of extensins in root defence we need to experimentally verify two important criteria. Are high levels of extensin deposited and, more importantly, are there higher levels of extensin intermolecular crosslinking in response to microbe attack? Castilleux et al. (2020) estimated the extensin levels in situ using immunolabelling with anti-extensin antibodies. Although we can be persuaded that extensins were highly expressed in root tips both before and after elicitation, the complicated antibody recognition patterns and pattern changes for each mutant after elicitation make it hard to explain the data, thus weakening the actual evidence. This is mainly because the specific epitope for each antibody remains unclear. Some of the epitopes may not be specific for extensin arabinosides. Moreover, as the authors emphasized, extensins function through oxidative crosslinking, but they failed to present the most critical evidence, the extensin crosslinking patterns (i.e. the amounts of di-isodityrosine, purcherosine and isodityrosine), in WT and mutant roots before and after elicitation and pathogen attack. This analysis would actually provide direct evidence that altered arabinosylation changes extensin crosslinking in vivo and is crucial to the real function of extensins in plant–microbe interactions.

In addition to immunolabelling, extensin deposition in root has been indirectly monitored through quantitative PCR analysis of target extensin genes. In the paper by Castilleux et al. (2020), it would have been of great interest to include the relative transcript levels of major root extensins, different extensin arabinosyltransferases and P4Hs before and after elicitor/pathogen treatment in each mutant. For example, in the rra1 mutant, what was the status of RRA2 and RRA3 gene expression during elicitation? This information might help us understand the complicated immunolabelling data (figure 4 in their paper) because the mutated genes in selected mutants have corresponding redundant genes that may complement the mutants. Here, gene redundancy weakens the significance of some of the mutant results.

Current studies on plant–microbe interactions are mainly from the microbe side or focus on the response pathways in plants. Very little research has dealt with plant cell-wall changes during the interaction, especially the alterations of different wall components in response to microbe attacks. However, understanding cell-wall modifications during microbe interactions is obviously important because the cell wall serves as the first line of plant cell defence. Castilleux et al. (2020) provided unique evidence regarding the important role of cell-wall extensins in this biological process. Specifically, Hyp-O-arabinosylation is critical for extensins to form an in vivo crosslinked network structure, which is crucial for the wall to resist pathogen colonization. A more detailed understanding of the mechanisms of how wall components are adjusted during this process should provide useful approaches for improving plant health and ultimately enhance crop productivity.

References

- Cannon MC, Terneus K, Hall Q, et al. 2008. Self-assembly of the plant cell wall requires an extension scaffold. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 105: 2226–2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castilleux R, Plancot B, Gugi B, et al. 2020. Extensin arabinosylation is involved in root response to elicitors and limits oomycete colonization. Annals of Botany 125: 751–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Dong W, Tan L, et al. 2015. Arabinosylation plays a crucial role in extension cross-linking in vitro. Biochemistry Insights 8: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shailasree S, Ramachandra K, Deepak BS, et al. 2004. Accumulation of hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins in pearl millet seedlings in response to Sclerospora graminicola infection. Plant Science 167: 1227–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Velasquez SM, Ricardi MM, Dorosz JG, et al. 2011. O-Glycosylated cell wall proteins are essential in root hair growth. Science 332: 1401–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei G, Shirsat AH. 2006. Extensin over-expression in Arabidopsis limits pathogen invasiveness. Molecular Plant Pathology 7: 579–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]