Abstract

Human coronaviruses SARS-CoV-2 appeared at the end of 2019 and led to a pandemic with high morbidity and mortality. As there are currently no effective drugs targeting this virus, drug repurposing represents a short-term strategy to treat millions of infected patients at low costs. Hydroxychloroquine showed an antiviral effect in vitro. In vivo it showed efficacy, especially when combined with azithromycin in a preliminary clinical trial. Here we demonstrate that the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin has a synergistic effect in vitro on SARS-CoV-2 at concentrations compatible with that obtained in human lung.

Keywords: 2019-nCoV, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Hydroxychloroquine, Azithromycin, Vero E6

1. Introduction

Since the end of 2019, the world has encountered pandemic conditions attributable to a novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV 2 [[1], [2], [3]]. This is the 7th Coronavirus identified to infect the human population [1,4,5] and the first one that had pandemic potential in non-immune populations in the 21st century [6]. Finding therapeutics is thus crucial, and it is proposed to do so by repurposing existing drugs [[7], [8], [9]]. This strategy presents the advantages that safety profiles of such drugs are known and that they could be easily produced at relatively low cost, thus being quicker to deploy than new drugs or a vaccine. Chloroquine, a decades-old antimalarial agent, an analog of quinine, was known to inhibit the acidification of intracellular compartments [10] and has shown in vitro and in vivo (mice models) activity against different subtypes of Coronaviruses: SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV, HCoV-229E and HCoV-OC43 [[11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]]. In 2004 it was tested in vitro against SARS-CoV [17] and caused a 99% reduction of viral replication after 3 days at 16 μM. Moreover, tests in vitro have shown inhibition of viral replication on SARS-CoV 2 detected by PCR and by CCK-8 assay [18]. Hydroxychloroquine (hydroxychloroquine sulfate; 7-Chloro-4-[4-(N-ethyl-N-b-hydroxyethylamino)-1-methylbutylamino]quinoline sulfate) has shown activity against SARS-CoV2 in vitro and exhibited a less toxic profile [19]. This drug is well known and currently used mostly to treat autoimmune diseases and also by our team to treat Q fever disease [20,21] and Whipple's disease [22,23]. In those clinical contexts, concentrations obtained in serum are close to 0.4–1 μg/mL at the dose of 600 mg per day over several months [24]. Clinical tests of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine to treat COVID-19 are underway in China [25], with such trials using hydroxychloroquine in progress in the US (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04307693) and in Europe with the Discovery Trial. In this drug repurposing effort, antibacterial components have also been tested. Teicoplanin, a glycopeptide, was demonstrated in vitro to inhibit cellular penetration of Ebola virus [26] and SARS-CoV 2 [26,27]. Azithromycin (azithromycin dihydrate), a macrolide, N-Methyl-11-aza-10-deoxo-10-dihydroerythromycin A, has shown antiviral activity against Zika [[28], [29], [30]]. Azithromycin is a well-known and safe drug, widely prescribed in the US, for example, with 12 million treatment courses in children under 19 years of age alone [31]. A recent study has identified these two compounds (azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine) among 97 total potentially active agents as possible treatments for this disease [32].

In a preliminary clinical study, hydroxychloroquine and, with even greater potency, the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin were found effective in reducing the SARS-CoV-2 viral load in COVID-19 patients [33]. Since the beginning of the epidemic in the Marseille region we isolated numerous strains and we tested one of them, the SARS-CoV-2 IHUMI-3, using different concentrations of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in combination, with Vero E6 cells.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Viral isolation procedure and viral stock

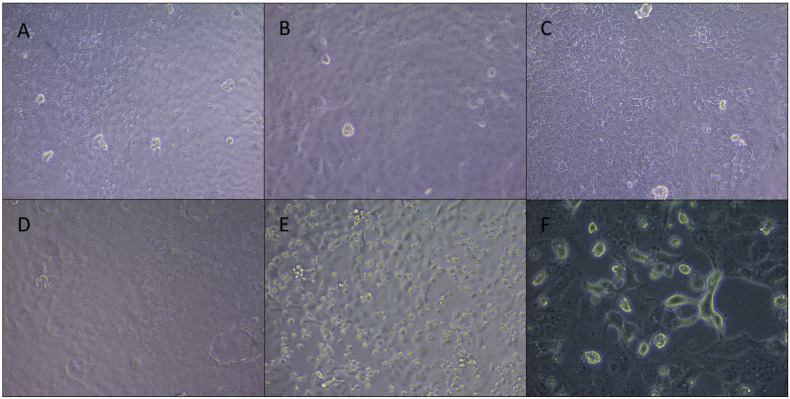

The procedure of viral isolation of our SARS-Cov 2 strain IHUMI-3 was detailed elsewhere [33]. The viral production was done in 75 cm2 cell culture flask containing Vero E6 cells (American type culture collection ATCC® CRL-1586™) in Minimum Essential Media (Gibco, ThermoFischer) (MEM) with 4% of fetal bovine serum and 1% glutamine. Cytopathic effect was monitored daily under an inverted microscope (Fig. 1 ). After nearly complete cell lysis (approximately 96 h), viral supernatant was used for inoculation on 96-well plate. We determined the TCID50 of the strain at 5.105 infectious particles per mL.

Fig. 1.

Observations of infected cells resistant or not to viral replication after inoculation of SARS-CoV 2 strain IHUMI-3 at MOI 0.25.

2.2. Testing procedure for drugs

Briefly, we prepared 96-well plates with 5.105 cells/mL of Vero E6 (200 μL per well), using MEM with 4% of fetal bovine serum and 1% l-glutamine. Plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C in a CO2 atmosphere. Drug concentrations tested, expressed in micromoles per liter (μM), were 1, 2 or 5 μM for hydroxychloroquine associated with 5 or 10 μM for azithromycin. Each test was done at least in triplicate and repeated two times except conditions with 5 μM for hydroxychloroquine associated with 5 or 10 μM for azithromycin that were repeated a third time. Four hours before infection, cell culture supernatant was removed and replaced by drugs diluted in the culture medium. At t = 0, virus suspension in culture medium was added to all wells except in negative controls where 50 μL of the medium was added. Multiplicity of infection (MOI) was of 0.25. Then RT-PCR was done 30 min post-infection in one plate and again at 60 h post-infection on a second plate. For this, 100 μL from each well was collected and added to 100 μL of the ready-use VXL buffer from QIAcube kit (Qiagen, Germany). The extraction was done using the manual High Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Roche Life Science), following the recommended procedures. The RT-PCR was done using the Roche RealTime PCR Ready RNA Virus Master Kit. The primers were designed against the E gene using the protocol of Amrane et al. [34] in the Roche LightCycler® 480 Instrument II. Relative viral quantification was done compare to the positive control (viruses without drugs) by the 2∧(–delta delta CT) method [35]. We performed a statistical analysis using GraphPad Prism v9.0.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA). Distribution of the data not followed a normal law. So, non parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare each combinations against positive controls using ΔCt between H0 and H60. Then, Dunn's test was used to correct the multiple comparison. All test was used at p = 0,05 parameter and were bilateral (two-sides) and significant P-value was indicated on Fig. 2 . All others conditions was not significant.

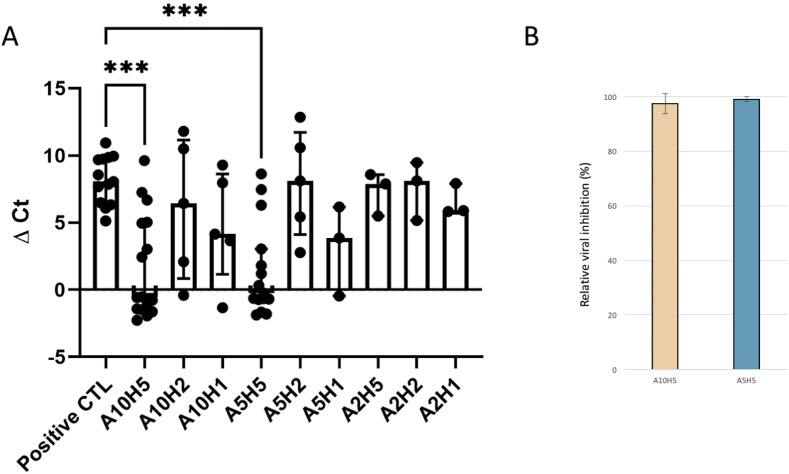

Fig. 2.

Effect of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin association on SARS-CoV 2 replication.

2A. Delta Ct between 0 and 60 h post infection. Ordered axis represents the variation of delta cycle-thresholds obtained by RT-PCR between H0 and H60 for each condition. Each point represents data obtained for one well. Number of replicates was indicated for each conditions are A10H5 n = 16, A10H2 n = 5, A10H1 n = 5, A5H5 n = 15, A5H2 n = 5, A5H1 n = 3, A2H5 n = 3, A2H2 n = 3, A2H1 n = 3 and n = 13 for the positive control. Median and interquartile range were indicated for each condition. *** represent significant results under p < 0,0005. Others are not significant compared to the control.

2B. Percentage of inhibition as compared to control by the combinations of 5 μM of hydroxychloroquine associated with 5 or 10 μM for azithromycin. Data represent the mean ± SD, representing three independent experiments conducted at least in triplicate.

3. Results

No cytotoxicity was associated with drugs in combination in all 13 control wells (without viruses). We detected RNA viral production from 25 to 16 cycle-thresholds (Ct, inversely correlated with RNA copy numbers) for the positive control that was associated with cell lyses. In all cases, cell lyses at 60 h was correlated with viral production as compared to control (Fig. 1). Combination of azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine led to significant inhibition of viral replication for wells containing hydroxychloroquine at 5 μM in combination with azithromycin at 10 and 5 μM (P-values at 0,0003 for A10H5 and at 0,0004 for A5H5) (Fig. 2A) with relative viral inhibition of 97.5% and 99.1% respectively (Fig. 2B). Others conditions were not significant. In agreement with the relative viral RNA load reduction, a cytopathic effect could be observed in 5/31 wells at 60 h post infection as compared to 13/13 in positive controls.

4. Discussion

In the work we identified a strong synergistic effect of the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin. Hydroxychloroquine has been demonstrated in vitro to inhibit replication of SARS-CoVs 1 and 2 [17,19]. Concentrations of drugs for our study were based on the known cytotoxicity of the drugs (50% of cytotoxicity, CC 50) and their effect on microorganisms (50% inhibitory concentration, IC50). With Zika virus, azithromycin showed activity with an IC 50 range from 2.1 to 5.1 μM depending on MOI [28] without notable effect on EC 50 at high concentration [29]. The observation of efficacy of azithromycin on RNA viruses is probably shared by some other macrolides. Clarithromycin or the non antibiotic macrolide EM900 were observed as effective on rhinovirus in vitro [[36], [37]]. In vivo sulfate of hydroxychloroquine could be imply in the modulation of the immune response by reducing pro-inflammatory cytokines and by modification of the lysosome acidification procedure [38]. Those aspects may play a keystone role in severe cases of SARS-coronaviruses. Indeed, in mouse models from SARS-CoV pneumonia and lung affections was associated with cytokines storm [39]. In parallel azithromycin was known as inhibit the viral replication of Zika virus in vitro [29]. And in enlarge viral infection context, azithromycin was associated to up-regulate interferons I and III [30]. Concerning the respiratory syncytial virus, it was also shown that Macrolides reduce the acidity of the lysosome and by the down-regulation of the ICAM-1 protein (36). So, in the SARS-CoV 2 context, azithromycin could potentialize the effect of hydroxychloroquine by similar mechanism.

On Vero E6 it was shown that for hydroxychloroquine, CC 50 is close to 250 μM (249.50 μM), which is significantly above the concentrations we tested herein [19]. Against SARS-CoV 2, the IC 50 of hydroxychloroquine was determined to be 4.51, 4.06, 17.31, and 12.96 μM with various MOI of 0.01, 0.02, 0.2, and 0.8, respectively.

One of the main criticisms of previously published data was that drug concentrations for viral inhibition used in vitro are difficult to translate clinically due to side effects that would occur at those concentrations. The synergy between hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin that we observed herein is at concentrations achieved in vivo and detected in serum [35] and pulmonary tissues (36–37) respectively. Our data are thus in agreement with the clinical efficacy of the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin observed by Gautret et al. [33]. They support the clinical use of this drug combination, especially at the early stage of the COVID-19 infection before the patients develop respiratory distress syndrome with associated cytokine storm and become less treatable by any antiviral treatment.

Funding

This research was funded by the French Government under the “Investissements d'avenir” (Investments for the Future) program managed by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR, French National Agency for Research), (reference: Méditerranée Infection 10-IAHU-03), by Région Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur and European funding FEDER PRIMI.

Author statement

Virus culture and drug testing: JA, ML, ID, NW; Molecular biology testing: PJ, CR, MB; Analyzed the results: JA, JMR, PC, BL, DR; Wrote the manuscript: JA, BL; Conceived the study: BL, DR.

Pictures were captured on ZEISS AxioCam ERC 5s, 58 h post infection. Magnitude X200.3A-B-C. overview of the monolayer in each well for the condition of azithromycin 5 μM associated with hydroxychloroquine at 5 μM, 3D. Negative control well and 3E. Positive control well. 1F. Observation was done 48 h post infection by the SARS-CoV 2 strain IHUMI-3 for the viral stock production. Magnitude X400.

Declaration of competing interest

Authors would like to declare that Didier Raoult is a consultant in microbiology for Hitachi High-Tech Corporation. Funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The others authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to David Scheim for background literature searching and editing the English version of this paper and Matthieu Million for statistical analysis.

References

- 1.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J., et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 Feb 20;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 Feb 28 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rothe C., Schunk M., Sothmann P., Bretzel G., Froeschl G., Wallrauch C., et al. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020 Mar 5;382(10):970–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaki A.M., van B.S., Bestebroer T.M., Osterhaus A.D., Fouchier R.A. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012 Nov 8;367(19):1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vabret A., Dina J., Gouarin S., Petitjean J., Tripey V., Brouard J., et al. Human (non-severe acute respiratory syndrome) coronavirus infections in hospitalised children in France. J. Paediatr. Child Health. 2008 Apr;44(4):176–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morens D.M., Folkers G.K., Fauci A.S. What is a pandemic? J. Infect. Dis. 2009 Oct 1;200(7):1018–1021. doi: 10.1086/644537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kruse R.L. Therapeutic strategies in an outbreak scenario to treat the novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China. F1000Res. 2020;9:72. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.22211.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai C.C., Shih T.P., Ko W.C., Tang H.J., Hsueh P.R. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): the epidemic and the challenges. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020 Mar;55(3):105924. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colson P., Rolain J.M., Lagier J.C., Brouqui P., Raoult D. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as available weapons to fight COVID-19. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020 Mar 4:105932. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohkuma S., Poole B. Fluorescence probe measurement of the intralysosomal pH in living cells and the perturbation of pH various agents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1978;75:3327–3331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.7.3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keyaerts E., Li S., Vijgen L., Rysman E., Verbeeck J., Van R.M., et al. Antiviral activity of chloroquine against human coronavirus OC43 infection in newborn mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009 Aug;53(8):3416–3421. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01509-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vincent M.J., Bergeron E., Benjannet S., Erickson B.R., Rollin P.E., Ksiazek T.G., et al. Chloroquine is a potent inhibitor of SARS coronavirus infection and spread. Virol. J. 2005 Aug 22;2:69. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-2-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savarino A., Boelaert J.R., Cassone A., Majori G., Cauda R. Effects of chloroquine on viral infections: an old drug against today's diseases? Lancet Infect. Dis. 2003 Nov;3(11):722–727. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00806-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Wilde A.H., Jochmans D., Posthuma C.C., Zevenhoven-Dobbe J.C., van N.S., Bestebroer T.M., et al. Screening of an FDA-approved compound library identifies four small-molecule inhibitors of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication in cell culture. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014 Aug;58(8):4875–4884. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03011-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kono M., Tatsumi K., Imai A.M., Saito K., Kuriyama T., Shirasawa H. Inhibition of human coronavirus 229E infection in human epithelial lung cells (L132) by chloroquine: involvement of p38 MAPK and ERK. Antivir. Res. 2008 Feb;77(2):150–152. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devaux C.A., Rolain J.M., Colson P., Raoult D. New insights on the antiviral effects of chloroquine against coronavirus: what to expect for COVID-19? Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020 Mar 11:105938. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keyaerts E., Vijgen L., Maes P., Neyts J., Van R.M. In vitro inhibition of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus by chloroquine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004 Oct 8;323(1):264–268. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.08.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L., Yang X., Liu J., Xu M., et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020 Mar;30(3):269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu J., Cao R., Xu M., Wang X., Zhang H., Hu H., et al. Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. Cell Discov. 2020;6:16. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0156-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raoult D., Houpikian P., Tissot-Dupont H., Riss J.M., Arditi-Djiane J., Brouqui P. Treatment of Q fever endocarditis : comparison of two regimens containing doxycycline and ofloxacin or hydroxychloroquine. Arch. Intern. Med. 1999;159(2):167–173. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raoult D., Drancourt M., Vestris G. Bactericidal effect of Doxycycline associated with lysosomotropic agents on Coxiella burnetii in P388D1 cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1512–1514. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.8.1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boulos A., Rolain J.M., Raoult D. Antibiotic susceptibility of Tropheryma whipplei in MRC5 cells. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48(3):747–752. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.3.747-752.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fenollar F., Puechal X., Raoult D. Whipple's disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007 Jan 4;356(1):55–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra062477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armstrong N., Richez M., Raoult D., Chabriere E. Simultaneous UHPLC-UV analysis of hydroxychloroquine, minocycline and doxycycline from serum samples for the therapeutic drug monitoring of Q fever and Whipple's disease. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2017 Aug 15;1060:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao J., Tian Z., Yang X. Breakthrough: chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies. Biosci. Trends. 2020 Feb 19;14(1):72–73. doi: 10.5582/bst.2020.01047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y., Cui R., Li G., Gao Q., Yuan S., Altmeyer R., et al. Teicoplanin inhibits Ebola pseudovirus infection in cell culture. Antivir. Res. 2016 Jan;125:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang J., Ma X., Yu F., Liu J., Zou F., Pan T., et al. Teicoplanin potently blocks the cell entry of 2019-nCoV. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.05.935387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Retallack H., Di L.E., Arias C., Knopp K.A., Laurie M.T., Sandoval-Espinosa C., et al. Zika virus cell tropism in the developing human brain and inhibition by azithromycin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016 Dec 13;113(50):14408–14413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618029113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bosseboeuf E., Aubry M., Nhan T., de Pina J.J., Rolain J.M., Raoult D., et al. Azithromycin inhibits the replication of Zika virus. J. Antivir. Antiretrovir. 2018;10(1):6–11. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li C., Zu S., Deng Y.Q., Li D., Parvatiyar K., Quanquin N., et al. Azithromycin protects against Zika virus infection by upregulating virus-induced type I and III interferon responses. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019 Sep 16 doi: 10.1128/AAC.00394-19. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fleming-Dutra K.E., Demirjian A., Bartoces M., Roberts R.M., Taylor T.H., Jr., Hicks L.A. Variations in antibiotic and azithromycin prescribing for children by geography and specialty-United States, 2013. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2018 Jan;37(1):52–58. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nabirothckin S., Peluffo A.E., Bouaziz J., Cohen D. 2020. Focusing on the unfolded protein response and autophagy related pathways to reposition common approved drugs against COVID-19. Preprints. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gautret P., Lagier J.C., Parola P., Hoang V.T., Meddeb L., Mailhe M., et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020 Mar 20:105949. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 34.Amrane S., Tissot-Dupont H., Doudier B., Eldin C., Hocquart M., Mailhe M., et al. Rapid viral diagnosis and ambulatory management of suspected COVID-19 cases presenting at the infections diseases referral hospital in Marseille, France, -January 31st to March 1st, 2020: a respiratory virus snapshot. Trav. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101663. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001 Dec;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morgene MF, Maurin C, Pillet S, Berthelot P, Morfin F, Pozzetto B, et al. HaCaT epithelial cells as an innovative novel model of rhinovirus infection and impact of clarithromycin treatment on infection kinetics. Virology. 2018 Oct;523:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2018.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lusamba KN, Nomura K, Kawase T, Ota C, Kubo H, Sato T, et al. The non-antibiotic macrolide EM900 inhibits rhinovirus infection and cytokine production in human airway epithelial cells. Physiol Rep. 2015;3(10) doi: 10.14814/phy2.12557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lusamba KN, Nomura K, Kawase T, Ota C, Kubo H, Sato T, et al. The non-antibiotic macrolide EM900 inhibits rhinovirus infection and cytokine production in human airway epithelial cells. Physiol Rep. 2015;3(10) doi: 10.14814/phy2.12557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen J, Lau YF, Lamirande EW, Paddock CD, Bartlett JH, Zaki SR, et al. Cellular immune responses to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) infection in senescent BALB/c mice: CD4+ T cells are important in control of SARS-CoV infection. J Virol. 2010 Feb;84(3):1289–1301. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01281-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]